5 |

Editors Who Became Directors |

||

One of the more interesting career developments in film has been the transition from editors to directors. Two of the most successful, Robert Wise and David Lean, are the subject of this chapter.

Is it necessary and natural for editors to become directors? The answer is no. Is editing the best route to directing? Not necessarily, but editing can be invaluable, as demonstrated by the subjects of this chapter. What strengths do editors bring to directing? Narrative clarity, for one: Editors are responsible for clarifying the story from all of the footage that the director has shot. This point takes on greater meaning in the following sampling of directors who have entered the field from other areas.

From screenwriting, the most famous contemporary writer who has tried his hand at directing is Robert Towne (Personal Best, 1982; Tequila Sunrise, 1988). Before Towne, notable writer-directors included Nunnally Johnson (The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, 1956) and Ben Hecht (Specter of the Rose, 1946). All of these writers are great with dialogue, and their screenplays spark with energy. As directors, however, their work seems to lack pace. Their dialogue may be energetic, but the performances of their actors are too mannered. In short, these exceptional writers are unexceptional directors. This, of course, does not mean that all writers become poor directors; consider Preston Sturges, Billy Wilder, and Joseph Mankiewicz, for example. What it does imply, though, is that the narrative skill of writing doesn't lead directly to a successful directing career.

A similar conclusion can be drawn from cinematography. The visual beauty of the camerawork of Haskell Wexler has not translated into directorial success (Medium Cool, 1969); nor have William Fraker (Monte Walsh, 1970) or Jack Cardiff (Sons and Lovers, 1958) found success. Even Nicolas Roeg (Don't Look Now, 1973; Walkabout, 1971; Track 29, 1989) has a problem with narrative clarity and pace in his directed films, although he has won a following. There are, however, a few exceptions worth noting. Jan de Bout had great success with Speed (1994), and Barry Sonnenfield has been developing a distinctive style (The Addams Family, 1991, and Get Shorty, 1995).

Producers from David Selznick (A Farewell to Arms, 1957) to Irwin Winkler (Guilty by Suspicion, 1991) have tried to direct with less success than expected. Again, the problems of narrative clarity and pace have defeated their efforts.

Only actors have been as successful as editors in their transition to directors. From Chaplin and Keaton to Charles Laughton (The Night of the Hunter, 1955) and recently Robert Redford (Ordinary People, 1980) and Kevin Costner (Dances with Wolves, 1990), actors have been able to energize their direction, and for them, the problems of pace and clarity have been less glaring. Nor are actors singular in their talents. Warren Beatty has been very successful directing comedy (Heaven Can Wait, 1977). Diane Keaton has excelled in psychological drama (Unstrung Heroes, 1995), Mel Gibson has excelled in directing action (Braveheart, 1995). And Clint Eastwood has crossed genres, directing exceptional Westerns (Unforgiven, 1992) and melodrama (The Bridges of Madison County, 1995). Most notable in this area has been the work of Elia Kazan, director of On the Waterfront and East of Eden, who was originally an actor, and John Cassavetes (Gloria, 1980; Husbands, 1970; Faces, 1968).

The key is pace and narrative clarity. These concerns, which are central to the success of an editor, are but one element in the success of a director. Equally important and visible are the director's success with performers and crew, ability to remain on budget (shooting along a time line rather than on the basis of artistic considerations alone), and ability to inspire confidence in the producer. Any of these qualities (and, of course, success with the audience) can make a successful director, but only success with the building blocks of film—the shots and how they are put together—will ensure an editor's success. Again, we come back to narrative clarity and pace, and again these can be important elements for the success of a director.

Thus, editing is an excellent preparation for becoming a director. To test this idea, we now turn to the careers of two directors who began their careers as editors: Robert Wise and David Lean.

ROBERT WISE

ROBERT WISE

Wise is probably best known as the editor of Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). Within two years, he codirected his first film at RKO. As with many American directors, Wise spent the next 30 years directing in all of the great American genres: the Western (Blood on the Moon, 1948), the gangster film (Odds Against Tomorrow, 1959), the musical (West Side Story, 1961), and the sports film (The Set-Up, 1949). He also ventured into those genres made famous in Germany: the horror film (The Body Snatcher, 1945), the science-fiction film (The Day the Earth Stood Still, 1951), and the melodrama (I Want to Live!, 1958).

These directorial efforts certainly illustrate versatility, but our purpose is to illustrate how his experience as an editor was invaluable to his success as a director. To do so, we will look in detail at three of his films: The Set-Up, I Want to Live!, and West Side Story. We will also refer to Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), The Day the Earth Stood Still, and The Body Snatcher.

When one looks at Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, the work of the editor is very apparent. Aside from audacious cutting that draws attention to technique (“Merry Christmas-.-.-.-and a Happy New Year”), the breakfast scene and the opening introduction to the characters and the town stand out as tours de force, set-pieces that impress us. They contribute to the narrative but also stand apart from it, as did the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin (1925). Although this type of scene is notable in many of Wise's directorial efforts, the deeper contribution of the editor to the film is not to be intrusive, but rather to edit the film so that the viewer is clearly aware of the story and its evolution, not the editing.

The tension between the invisible editor and the editor of consciously audacious sequences is a tension that runs throughout Wise's career as a director. The equivalents of the breakfast scene in Citizen Kane emerge often in his work: the fight in The Set-Up, the dance numbers in West Side Story, and the opening of I Want to Live! As his career as a director developed, he was able to integrate the sequences into the narrative and make them revealing. A good example of this is the sampan blockade of the American ship in The Sand Pebbles (1966).

Another use Wise found for the set-piece is to elaborate a particular idea through editing. For example, in The Day the Earth Stood Still, Wise communicated the idea that every nation on Earth can be unified in the face of a great enough threat. To elaborate this idea, he cut sound and picture to different newsrooms around the world. The announcers speak different languages, but they are all talking about the same thing: an alien has landed, threatening everyone on the planet. Finally, the different nationalities are unified, but it has taken an alien threat to accomplish that unity. The idea is communicated through an editing solution, not quite a set-piece, but an editing idea that draws some attention to itself.

Wise used the same editing approach in Somebody Up There Likes Me to communicate the wide support for Rocky Graziano in his final fight. His family, his Hell's Kitchen friends, and his new fans are all engaged in “praying” at their radios that his fate in the final fight will mean something for their fate. By intercutting between all three groups, Wise lets us know how many people's dreams hang on the dream of one man. Here, too, the editing solution communicates the idea. Not as self-conscious as the breakfast scene in Citizen Kane, this sequence is nevertheless a set-piece that has great impact.

The principle of finding an editing solution to an idea surfaces early in Wise's career as a director. In The Body Snatcher, Wise had to communicate that Grey (the title character) has resorted to murder to secure a body for dissection at the local medical school. We don't see the murder, just the street singer walking through the foggy night-bound Edinburgh street. Her voice carries on. Grey, driving his buggy, follows. Both disappear. We see the street and hear the voice of the street singer. The shot holds (continues visually), as does the voice, and then nothing. The voice disappears. The visual remains. We know that the girl is dead and a new body will be provided for “science.” The scene has the elements of a set-piece, an element of self-consciousness, and yet it is extremely effective in heightening the tension and drama of the murder that has taken place beyond our sight.

We turn now to a more detailed examination of three of Wise's films, beginning with The Set-Up.

THE SET-UP (1949)

The Set-Up is the story of Stoker Thompson's last fight. Stoker is 35 and nearing the end of his career; he is low on the fight card but has the will to carry on. He fights now in a string of small towns and earns little money.

This screen story takes place entirely on the evening of the fight. Stoker's manager has agreed to have his fighter lose to an up-and-coming boxer, Tiger Nelson. But the manager, greedy and without confidence in Stoker, keeps the payoff and neglects to tell Stoker he is to lose.

Struggling against the crowd, against his wife who refuses to watch him beaten again, and against his manager, Stoker fights, and he wins. Then he faces the consequences. He has been true to himself, but he has betrayed the local gangster, Little Boy, and he must pay the price. As the film ends, Stoker's hand is broken by Little Boy, and the fighter acknowledges that he'll never fight again.

The Set-Up may be Wise's most effective film. The clarity of story is unusual, and a powerful point of view is established. Wise managed to establish individuals among the spectators so that the crowd is less impersonal and seems composed of individuals with lives before and after the fight. As a result, they take on characteristics that make our responses to Stoker more varied and complex.

Like Citizen Kane, the narrative structure poses an editing problem. With Citizen Kane, two hours of screen time must tell the story of one man's 75-year life. In The Set-Up, the story takes place in one evening. Wise chose to use screen time to simulate real time. The 72 minutes of the film simulate those 70 or so minutes of the fight, the time leading up to it, and its aftermath. As much as possible, Wise matched the relationship between real time and screen time.

That is not to say that The Set-Up is a documentary. It is not. It is a carefully crafted dramatization of a critical point in Stoker's life: his last fight.

To help engage us with Stoker's feelings and his point of view, Wise used subjective camera placement and movement. We see what Stoker sees, and we begin to feel what he must feel. Wise was very pointed about point of view in this film.

This film is not exclusively about Stoker's point of view, however. Wise was as subjective about Stoker's wife and about seven other secondary characters or groups of characters and their points of view. All witness the fight, but some have a direct interest: the manager, his assistant, and Little Boy and his contingent. Five spectators are highlighted: a newspaper seller (probably a former boxer), a blind man, a meek man, an obese man, and a belligerent housewife. With the exceptions of the newspaper seller and the obese man, all have companions whose behavior stands out in contrast to their own.

The film introduces each of these spectators before the fight and cuts away to them continually throughout the fight. The camera is close and looks down or up at them (it is never neutral). Wise used an extreme close-up only when the housewife yells to Stoker's opponent, “Kill him!” All of the spectators seem to favor Nelson with much verbal and physical expression. If they could be in the ring themselves, they would enjoy the ultimate identification. Only when the fight begins to go against Nelson do they shift allegiances and yell their support for Stoker. The spectators do not appear superficially to be bloodthirsty, but their behavior in each case speaks otherwise.

Wise carried the principle of subjectivity as far as he could without drawing too much attention to it. He used silence as Hitchcock did in Blackmail. Before the fight, individual disparaging comments about his age and his chances are heard by Stoker. As he spars with his opponent, the two become sufficiently involved with one another that they can actually exchange words in spite of the din. Between rounds, Stoker is so involved in regrouping his physical and mental resources that for a few brief seconds, he hears nothing. Almost total silence takes over until the bell rings Stoker, and us, back into the awareness that the next round has begun. Sound continues to be used invasively. It surrounds, dominates, and then recedes to simulate how Stoker struggles for some mastery within his environment.

In The Set-Up, Wise suggested that Stoker's inner life with its tenacious will to see himself as a winner contrasts with his outer life, his life in society, which views him as a fighter in decline, one step removed from being a discard of society. So great is the derision toward him from the spectators that the audience begins to feel that they too struggle with this inner life–outer life conflict and they don't want to identify with a loser. These are the primary ideas that Wise communicates in this film, and by moving away from simple stereotypes with most of the people in the story, he humanizes all of them. These ideas are worked out with editing solutions. Both picture and sound, cutaways and close-ups, are used to orchestrate these ideas.

I WANT TO LIVE! (1958)

In I Want to Live!, Wise again dealt with a story in which the inner life of the character comes into conflict with society's view of that person (Figure 5.1). In this case, however, the consequences of the difference are dire. In the end, the main character is executed by society for that difference.

Barbara Graham enjoys a good time and can't seem to stay out of trouble. She perjures herself casually and thus begins her relationship with the law. She lives outside the law but remains a petty criminal until circumstance leads her to be involved with two men in a murder charge. Now a mother, her defiant attitude leads to a trial where poor judgment in a man again deepens her trouble. This time she is in too far. She is sentenced to be executed for murder. Although a psychologist and reporter try to save her, they are too late. The film ends shortly after she has been executed for a murder she did not commit.

Figure 5.1 |

I Want to Live!, 1958. ©1958 United Artists Corporation. All rights reserved. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

I Want to Live! is a narrative that takes place over a number of years. Wise's first challenge was to establish an approach or attitude that would set the tone but also allow for an elaborate narrative. Wise created the equivalent of a jazz riff. Set to Gerry Mulligan's combo performance, he presented a series of images set in a jazz club. The combo performs. The customers pair off, drink, and smoke. This is an atmosphere that tolerates a wide band of behavior, young women with older men, young men at the margin of the law. A policeman enters looking for someone, but he doesn't find her. Only his determination singles him out from the rest.

This whole sequence runs just over 2 minutes and contains fewer than 20 shots. All of the images get their continuity from two sources: the combo performance and the off-center, deep-focus cinematography. All of the images are shot at angles of up to 30 degrees. The result is a disjointed, unstable feeling. There is unpredictability here; it's a visual presentation of an off-center world, a world where anything can happen. There is rhythm but no logic here, as in a jazz riff. The pace of the shots does not help. Pace can direct us to a particular mood, but here the pace is random, not cueing us about how to feel. Randomness contributes to the overall mood. This is Barbara Graham's world. This opening sequence sets the tone for what is to follow in the next 2 hours.

After this prologue, Wise still faced the problem of a screen story that must cover the next 8 to 10 years. He chose to straight-cut between scenes that illustrate Graham's steady decline. He focused on those periods or decisions she made that took her down the road to execution. All of the scenes center around her misjudgments about men. They include granting ill-considered favors, committing petty crime, marrying a drug addict, returning to criminal companions, and a murder charge for being found with those companions. Once charged, she mistrusts her lawyer but does trust a policeman who entraps her into a false confession about her whereabouts on the night of the murder. Only when it is too late does her judgment about a male psychologist and a male reporter suggest a change in her perception, but by relentlessly snubbing her nose at the law and society, she dooms herself to death (this was, after all, the 1950s).

By straight-cutting from scene to scene along a clear narrative that highlights the growing seriousness of her misjudgments, Wise blurred the time issue, and we accept the length of time that has passed. There are, however, a few notable departures from this pattern—departures in which Wise introduced an editorial view. In each case, he found an editing solution.

An important idea in I Want to Live! is the role of the media, particularly print and television journalism, and the role they played in condemning Graham. Wise intercut the murder trial with televised footage about it. He also intercut direct contact between Graham and the print press, particularly Ed Montgomery. By doing this, Wise found an editing solution to the problem of showing all of the details of the actual trial on screen and also found a way to illustrate the key role the media played in finding Graham guilty. This is the same type of intercutting seen in The Day the Earth Stood Still and Somebody Up There Likes Me.

Another departure is the amount of screen time Wise spent on the actual execution. The film meticulously shows in close-up all of the details of the execution: the setting, its artifacts, the sulfuric acid, how it works, the cyanide, how it works, how the doctor checks whether Barbara is dead. All of these details show an almost clinical sense of what is about to happen to Barbara and, in terms of the execution, of what does happen to her. This level of detail draws out the prelude to and the actual execution. The objectivity of this detail, compared to the randomness of the jazz riff, is excruciating and inevitable—scientific in its predictability. This sequence is virtually in counterpoint to the rest of the film. As a result, it is a remarkably powerful sequence that questions how we feel about capital punishment. The scientific presentation leaves no room for a sense of satisfaction about the outcome. Quite the contrary, it is disturbing, particularly because we know that Graham is innocent.

The detail, the pace, and the length of the sequence all work to carry the viewer to a sense of dread about what is to come, but also to editorialize about capital punishment. It is a remarkable sequence, totally different from the opening, but, in its way, just as effective. Again, Wise found an editing solution to a particular narrative idea.

WEST SIDE STORY (1961)

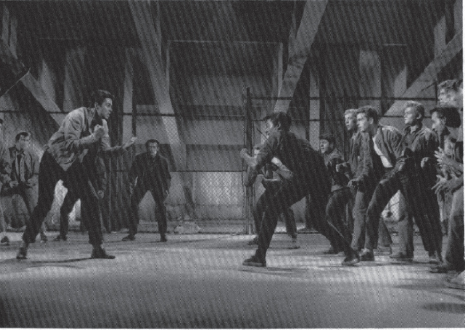

Leonard Bernstein's West Side Story (1961) is a contemporary musical adaptation of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. Instead of the Montagues and the Capulets, however, the conflict is between two New York street gangs: the Sharks and the Jets (Figure 5.2). The Sharks are Puerto Rican. Their leader is Bernardo (George Chakiris). The Jets are American, although there are allusions to their ethnic origins as well. Their leader is Riff (Russ Tamblyn). The Romeo and Juliet of the story are Tony (Richard Beymer), a former Jet, and Maria (Natalie Wood), Bernardo's sister. They fall in love, but their love is condemned because of the animosity between the two gangs. When Bernardo kills Riff in a rumble, Tony kills Bernardo in anger. It's only a matter of time before that act of street violence results in his own death.

West Side Story was choreographed by Jerome Robbins, who codirected the film with Robert Wise. Although the film is organized around a Romeo and Juliet narrative and Bernstein's brilliant musical score, the editing is audacious, stylized, and stimulating.

The opening sequence, the introduction to New York and the street conflict of the Sharks and the Jets, runs 10 minutes with no dialogue. In these 10 minutes, the setting and the conflict are introduced in a spirited way. Wise began with a series of helicopter shots of New York. There are no street sounds here, just the serenity of clear sightlines down to Manhattan. For 80 seconds, Wise presented 18 shots of the city from the helicopter. The camera looks directly down on the city. The movement, all of it right to left, is gentle and slow, almost elegant. Little sound accompanies these camera movements. Many familiar sights are visible, including the Empire State Building and the United Nations. We move from commercial sights to residential areas. Only then do we begin to descend in a zoom and then a dissolve.

The music comes up, not too loud. We are in a basketball court between two tenements. A pair of fingers snap and we are introduced to Riff, the leader of the Jets, and then to another Jet and then to a group of Jets. The earlier cutting had no sound cues; now the cuts occur on the beat created by the snap of fingers. The Jets begin to move right to left, as the helicopter did. This direction is only violated once—to introduce the Jets’ encounter with Bernardo, a Shark. The change in direction alludes to the conflicts to come.

Figure 5.2 |

West Side Story, 1961. ©1961 United Artists Pictures, Inc. All rights reserved. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

The film switches to the Sharks, and as Bernardo is joined by his fellow gang members, they are introduced in close-ups, now moving left to right. When the film cuts to longer shots, we notice that the Sharks are photographed with less context and more visual entrapment. For example, as they move up alleys, the walls on both sides of the alley trap them in midframe. This presentation of the Sharks also differentiates them from the Jets, who appear principally in midshot with context and with no similar visual entrapment.

The balance of the sequence outlines the escalating conflict between the two gangs. They taunt and interfere with each other's activities. Throughout, the Jets are filmed from eye level or higher, and the Sharks are usually filmed from below eye level. The Jets are presented as bullies exploiting their position of power, and the Sharks are shown in a more heroic light. The sequence culminates in an attack by the Sharks on John Boy, who has been adding graffiti to Shark iconography. For the first time in the sequence, the Sharks are photographed from above eye level as they beat and maim John Boy. This incident leads to the arrival of the police and to the end of this 10-minute introduction. The conflict is established.

Because of the length of this sequence, the editing itself had to be choreographed to explain fully the conflict and its motivation and to differentiate the two sides. Wise was even able to influence us to side with the outsiders, the Sharks, because of the visual choices he made: the close-ups, the sense of visual entrapment, and the heroic camera angle. All suggest that we identify with the Sharks rather than with the Jets.

The other interesting sequence in West Side Story is the musical number “Tonight.” As with the opera sequence in Citizen Kane and the fight sequence in Somebody Up There Likes Me, Wise found a unifying element, the music or the sounds of the fight, and relied on the sound carry-over throughout the sequence to provide unity.

“Tonight” includes all of the components of the story. Bernardo, Riff, the Sharks, and the Jets get ready for a rumble; Tony and Maria anticipate the excitement of being with one another, Anita prepares to be with Bernardo after the fight, and the lieutenant anticipates trouble. Wise constructed this sequence slowly, gradually building toward the culmination of everyone's expectations: the rumble. Here he used camera movement, camera direction, and increasingly closer shots (without context) to build the sequence. He also used a faster pace of editing to help build excitement.

Whereas in the opening sequence, pace did not play a very important role, in the “Tonight” sequence, pace is everything. Cross-cutting between the gangs at the end of the song takes us to the moment of great anticipation—the rumble—with a powerful sense of preparation; the song has built up anticipation and excitement for what will happen next. The music unifies this sequence, but it is the editing that translates it emotionally for us.

DAVID LEAN

DAVID LEAN

Through his experience in the film industry, including his time as an assistant editor and as an editor, David Lean developed considerable technical skill. By the time he became codirector of In Which We Serve (1942) with Noel Coward, he was ready to launch into directing. As a director, he developed a visual strength and a literary sensibility that makes his work more complex than the work of Robert Wise. Lean's work is both more subtle and more ambitious. His experience as an editor is demonstrable in his directing work. Although Lean made only 15 films in a career of more than 40 years, many of those films have become important in the popular history of cinema. His pictorial epics, Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965), remain the standard for this type of filmmaking. His romantic films, Brief Encounter (1945) and Summertime (1955), are the standard for that type of filmmaking. His literary adaptations, Great Expectations (1946) and Hobson's Choice (1954), are classics, and The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) remains an example of an intelligent, entertaining war film with a message. Lean may have made few films, but his influence has far exceeded those numbers. The role of editing in his films may help explain that influence.

To establish context for his influence, it is critical to acknowledge Lean's penchant for collaborators: Noel Coward worked on his first three films, Anthony Havelock Allan and Ronald Neame collaborated on the films that followed, and Robert Bolt and Freddie Young worked on Lawrence of Arabia and the films that followed (except Passage to India, 1984). Also notable are Lean's visual strengths. Few directors have created more extraordinary visualizations in their films. The result is that individual shots are powerful and memorable. The shots don't contradict Pudovkin's ideas about the interdependency of shots for meaning, but they do soften the reliance on pace to shape the editorial meaning of the shots. Lean seems to have been able to create considerable impact without relying on metric montage. That is not to say that there is no rhythm to his scenes. When he wished to use pace, he did so carefully (as he did in the British captain's war memories in Ryan's Daughter [1970]). However, Lean seems to have been sufficiently self-assured as a director that his films rely less on pace than is the case with many other directors.

To consider his work in some detail, we will examine Brief Encounter, Great Expectations, The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lawrence of Arabia, and Doctor Zhivago.

LEAN'S TECHNIQUE

Directors who are powerful visualists are memorable only when their visuals serve to deepen the story. The same is true about sound. Good directors involve us with the story rather than with their grasp of the technology. Editing is the means used to illuminate the story's primary meaning as well as its levels of meaning. By looking at Lean's style, we can see how he managed to use the various tools of editing.

Sound

In his use of sound, Lean was very sophisticated. He used the march, whistled and orchestrated, in The Bridge on the River Kwai, and in each case, its meaning was different. His use of Maurice Jarre's music in Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, and Ryan's Daughter is probably unprecedented in its popular impact. However, it is in the more subtle uses of sound that Lean illustrated his skill. Through an interior monologue, Laura acts first as narrator and then confessor in Brief Encounter. Her confession creates a rapid identification with her.

A less emphatic use of sound occurs in Great Expectations. As Pip's sister is insulting the young Pip, Lean blurred the insults with the sound of an instrument. The resulting distortion makes the insults sound as if they were coming from an animal rather than a human. She is both menacing and belittled by the technical pun.

A similar surprise occurs in an action sequence in The Bridge on the River Kwai. British commandos are deep in the Burmese forest. Their Burmese guides, all women, are bathing. A Japanese patrol happens upon them. The commandos hurl grenades and fire their machine guns. As the noise of murder grows louder, the birds of the area fly off frightened, and as Lean cut visuals of the birds in flight, the sound of the birds drown out the machine guns. At that instant, nature quite overwhelms the concerns of the humans present, and for that moment, the outcome of human conflict seems less important.

Narrative Clarity

One of the problems that editing attempts to address is to clarify the story line. Screen stories tend to be told from the point of view of the main character. There is no confusion about this issue in Lean's stories. Not only was he utterly clear about the point of view, he introduced us to that point of view immediately. In Great Expectations, Pip visits the graveyard of his parents and runs into a frightening escaped convict (who later in the story becomes his surrogate father). The story begins in a vivid way; the point of view subjectively presented is that of the young boy. Through the position of the camera, Lean confirmed Pip's point of view. We see from his perspective, and we interpret events as he does: The convict is terrifying, almost as terrifying as his sister.

Lean proceeds in a similar fashion in Lawrence of Arabia. The film opens with a 3-minute sequence of Lawrence mounting his motorbike and riding through the British countryside. He rides to his death. Was it an accident, or, given his speed on this narrow country road, was it willful? Who was this man? Because the camera is mounted in front of him and sees what he sees, this opening is entirely subjective and quite powerful. By its end, we are involved, and the character has not said a word.

In Brief Encounter, the opening scene is the last time that the two lovers, Laura (Celia Johnson) and Alex (Trevor Howard), will be together. Because of a chatty acquaintance of Laura's, they can't even embrace one another. He leaves, and she takes the train home, wondering whether she should confess all to her husband. This ending to the relationship becomes the prologue to her remembrance of the whole relationship, which is the subject of the film. We don't know everything after this prologue, but we know the point of view—Laura's—and the tone of loss and urgency engages us in the story. The point of view never veers from Laura. Lean used a similar reminiscence prologue in another romantic epic, Doctor Zhivago.

Subjective Point of View

The use of subjective camera placement has already been mentioned, but subjective camera placement alone doesn't account for the power Lean's sequences can have. The burial scene in Doctor Zhivago illustrates this point. In 32 shots running just over 3 minutes, Lean re-created the 5-year-old Yuri Zhivago's range of feelings at the burial of his mother.

The sequence begins in extreme long shot. The burial party proceeds. Twothirds of the frame are filled by sky and mountains. The procession is a speck on a landscape. The film cuts to a moving track shot in front of a 5-year-old child. In midshot, at the boy's line of vision, we see him march behind a casket carrying his mother. He can barely see her shape. Soon, he stands by the graveside. A priest presides over the ceremony. Adults are in attendance, but the boy sees only his mother and the trees. When she is covered and then lowered into the ground, he imagines her under the ground, he sees her, he is beside her (given the camera's point of view), and he is aware of the rustle of trees. There is much feeling in this scene, yet Yuri does not cry. He doesn't speak, but we understand his depth of feeling and its lack of comprehension. We are with him. Camera, editing, and music have created these insights into the young Yuri at this critical point in his life.

The subjective point of view is critical if the narrative is to be clear and compelling.

Narrative Complexity

A clear narrative doesn't mean a simple narrative. Indeed, one characteristic of Lean's work that continues to be apparent as his career unfolds is that he is interested in stories of great complexity: India, Arabia, Ireland during troubled times. Even his literary adaptations are ambitious, and he always faces the need to keep the stories personally engaging.

The consequence has been a style that takes advantage of action sequences that occur in the story when they add to the story. The revolt of the army against its officers in Doctor Zhivago adds meaning to the goal of the revolution—the destruction of the class hierarchy—and this is central to the fate of Yuri and Lara. Can love transcend revolution?

The two sequences involving the capture of the convict-patron in Great Expectations also share complex narrative goals. In the first sequence, Pip is the witness to the soldier's tracking down the man to whom he had brought food. The sequence is filled with sky and the foreboding of the marsh fog. Later in the story, Pip himself is trying to save the convict from capture. He has come to view this man as a father, and he feels obligated to help. Now, at sea again, the escape is foiled by soldiers. The dynamism of this sequence is different from the first sequence, but it is horrifying in another way. It confirms the impossibility of rising above one's circumstances, a goal Pip has been attempting for 20 years of his short life. The action, the escape attempt, is dynamic, but its outcome is more than failure; it becomes a comment on social opportunity.

Pace

Lean did not rely on pace as much as other directors working in similar genres. That is not to say that the particular sequences he created don't rely on the tension that more rapid pace implies. It's just that it is rare in his films. One such sequence whose success does rely on pace is all the more powerful because it's a complex sequence, and as the climax of the film, it is crucial to its success: the climax of The Bridge on the River Kwai.

The group of three commandos has arrived in time to destroy the bridge as the Japanese troop train crosses it. They had laid explosive charges under the bridge that night. Now they await day and the troop train. The injured commando (Jack Hawkins) is atop the hill above the bridge. He will use mortars to cover the escape. A second commando (Geoffrey Horne) is by the river, ready to detonate the charge that will destroy the bridge. The third (William Holden) is on the other side of the river to help cover his colleagues’ escape.

It is day, and there are two problems. First, the river's water level has gone down, and some of the detonation wires are now exposed. Second, the proud Colonel Nicholson (Alec Guinness) sees the wires and is concerned about the fate of the bridge. He is proud of the achievement. His men have acted as men, not prisoners of war. Nicholson has lost sight of the fact that his actions, helping the enemy, might be treason. He calls to Saito (Sessue Hayakawa), the Japanese commander, and together they investigate the source of the demolition wires. He leads Saito to the commando on demolition. The intercutting between the discovery and the reaction of the other commandos—“Use your knife, boy” (Hawkins) and “Kill him” (Holden)—leads in rapid succession to Saito's death and to the commando's explanation that he is here to destroy the bridge and that he's British, too. The explanation is to no avail. Nicholson calls on the Japanese to help. The commando is killed. Holden swims over to kill Nicholson, but he too is killed. Hawkins launches a mortar that seriously injures Nicholson, who, at the moment of death, ponders on what he has done. The troop train is now crossing the bridge. Nicholson falls on the detonator and dies. The bridge explodes, and the train falls into the Kwai River. The mission is over. All of the commandos but one are dead, as are Nicholson and Saito. The British doctor (a prisoner of war of the Japanese) comments on the madness of it all. Hawkins reproaches himself by throwing the mortar into the river. The film ends.

The tension in this long scene is complex, beginning with whether the mission will be accomplished and how. Who will survive? Who will die? The outcomes are all surprising, and as the plot turns, the pacing increases and builds to the suspenseful end.

Lean added to the tension by alternately using subjective camera placement and extreme long shots and midshots. The contrast adds to the building tension of the scene.

LEAN'S ART

Like all directors, David Lean had particular ideas or themes that recurred in his work. How he presented those themes or integrated them into his films is the artful dimension of his work.

Lean made several period films and used exotic locations as the backdrop for his stories. For him, the majesty of the human adventure lent a certain perspective that events and behavior are inscrutable and noble, the very opposite to the modern day penchant for scientific rationalism. Whether this means that he was a romantic or a mystic is for others to determine; it does mean that nature, the supernatural, and fate all play roles, sometimes cruel roles, in his films. He didn't portray cruelty in a cynical manner but rather as a way of life. His work is the opposite of films by such people as Stanley Kubrick for whom technology played a role in meeting and molding nature.

How does this philosophy translate into his films? First, the time frame of his film is large: 20 years in Great Expectations and Lawrence of Arabia, 40 years in Doctor Zhivago. Second, the location of his films is also expansive. Oliver Twist (1948) ranges from countryside to city. Lawrence of Arabia ranges from continent to continent. The time and the place always have a deep impact on the main character. The setting is never decorative but rather integral to the story.

A powerful example of Lean's use of time, place, and character can be found in Lawrence of Arabia. In one shot, Lawrence demonstrates his ability to withstand pain. He lights a match and, with a flourish, douses it with his fingers. As the flame is extinguished, the film cuts to an extreme long shot of the rising sun in the desert. The bright red glow dominates the screen. In the lower part of the screen, there are a few specks, which are identified in a follow-up shot as Lawrence and a guide. The cut from a midshot of the match to an extreme long shot of the sun filling the screen is shocking but also exhilarating. In one shot, we move five hundred miles into the desert. We are also struck in these two shots by the awesome, magnificent quality of nature and of the insignificance of humanity. Whether this wonderment speaks to a supernatural order or to Lawrence's fate in the desert, we don't know, but all of these ideas are generated by the juxtaposition of two images. The cut illustrates the power of editing to generate a series of ideas from two shots. This is Lean's art: to lead us to those ideas through this juxtaposition.

An equally powerful but more elaborate set of ideas is generated by the attack on the Turkish train in Lawrence of Arabia. Using 85 shots in 6 minutes and 40 seconds, Lean created a sense of the war in the desert. The visuals mix beauty (the derailment of the train) and horror (the execution of the wounded Turkish soldier). The sequence is dynamic and takes us through a narrative sequence: the attack, its details, the aftermath, its implications for the next campaign, Lawrence's relationship to his soldiers. When he is wounded, we gain an insight into his masochistic psychology. Immediately thereafter, he leaps from train car to train car, posing shamelessly for the American journalist (Arthur Kennedy). In the sequence, we are presented with the point of view of the journalist, Lawrence, Auda (Anthony Quinn), Sharif Ali (Omar Sharif), and the British captain (Anthony Quayle).

This sequence becomes more than a battle sequence; Lean infused it with his particular views about heroes and the role they play in war (Figure 5.3). The battle itself was shot using many point-of-view images, principally Lawrence's point of view. Lean also used angles that give the battle a sense of depth or context. This means compositions that have foreground and background. He also juxtaposed close and medium shots with extreme long shots. Finally, Lean used compositions that include a good deal of the sky—low angles—to relate the action on the ground to what happens above it. Looking up at the action suggests a heroic position. This is particularly important when he cut from a low angle of Lawrence atop the train to a high-angle tracking shot of Lawrence's shadow as he leaps from train car to train car. By focusing on the shadow, he introduced the myth as well as the man. The shot is a vivid metaphor for the creation of the myth. This battle sequence of less than 7 minutes, with all of its implied views about the nature of war and the combatants, also contains a subtextual idea about mythmaking, in this case, the making of the myth of Lawrence of Arabia. This, too, is the art of Lean as editor-director.

Figure 5.3 |

Lawrence of Arabia. Copyright © 1962, Revised 1990, Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All rights reserved. Still courtesy British Film Institute. |

David Lean and Robert Wise provide us with two examples of editors who became directors. To take us more deeply into the relationship of the editor and the director, we turn now to the work of Alfred Hitchcock.