25 |

The Picture Edit and Continuity |

||

Much has been written suggesting that the art of film is editing,1 and numerous filmmakers from Eisenstein to Welles to Peckinpah have tried to prove this point. However, just as much has been written suggesting that the art of film is avoidance of editing,2 and filmmakers from Renoir to Ophuls to Kubrick have tried to prove that point. No one has managed to reconcile these theoretical opposites; this fascinating, continuing debate has led to excellent scholarship,3 but not to a definitive resolution. Both factions, however, work with the same fundamental unit: the shot. No matter how useful a theoretical position may be, it is the practical challenge of the director and the editor to work with some number of shots to create a continuity that does not draw unnecessary attention to itself. If it does, the filmmaker and the editor have failed to present the narrative in the most effective possible manner.

The editing process can be broken down into two stages: (1) the stage of assembling the shots into a rough cut and (2) the stage in which the editor and director fine-tune or pace the rough cut, transforming it into a fine cut. In the latter stage, rhythm and accentuation are given great emphasis. The goal is an edited film that is not only continuous, but also dramatically effective. The goal of the rough cut—the development of visual and sound continuity—is the subject of this chapter; the issue of pace is the subject of Chapter 26. Both chapters attempt to present pragmatic, rather than theoretical, solutions to the editing problem because, in the end, the creativity of editing is based on pragmatic solutions.

The editing problem begins with the individual shot. Is it a still image or a moving image? Is the foreground or the background in focus? How close is the character to the frame? Is the character positioned in the center or off to one side? What about the light and color of the image and the organization of objects or people relative to the main character? A great variety of factors affect the continuity that results when two shots are juxtaposed. The second shot must have some relationship to the first shot to support the illusion of continuity.

The simplest film, the one that respects continuity and real time, is the film that is composed of a single, continuous shot. The film would be honest in its representation of time and in its rendering of the subject, but it probably wouldn't be very interesting. Griffith and those who followed were motivated by the desire to keep audiences involved in the story. Their explorations focused on how little, rather than how much, needs to be shown. They discovered that it isn't necessary to show everything. Real time can be violated and replaced with dramatic time.

The premise of not needing to show everything leads quite logically to the question of what it is necessary to show. What elements of a scene will, in a series of shots, provide the details needed to direct the audience toward what is more important as opposed to less important? This is where the choice of the type of shot—the long shot versus the midshot, the midshot versus close-up—comes into play. This is also where decisions about camera placement—objective or subjective—come into play. The problem for the editor is to choose the shot that best serves the film's dramatic purpose. Another problem follows: Having chosen the shot, how does the editor cut the shot together with the next one so that together they provide continuity? Without continuity (for example, if the editor cuts from one close-up to another that is unrelated), viewers become confused. Editing should never confuse viewers; it should always keep them informed and involved in the story.

Narrative clarity is achieved when a film does not confuse viewers. It requires matching action from shot to shot and maintaining a clear sense of direction between shots. It means providing a visual explanation if a new idea or a cutaway is introduced. To provide narrative clarity, visual cues are necessary, and here, the editor's skill is the critical factor.

CONSTRUCTING A LUCID CONTINUITY

CONSTRUCTING A LUCID CONTINUITY

Seamlessness has become a popular term to describe effective editing. A seamless, or smooth, cut is the editor's first goal. A seamless cut doesn't draw attention to itself and comes at a logical point within the shot. What is that logical point? It is not always obvious, but viewers always notice when an inappropriate edit point has been selected. For example, suppose that a character is crossing the room in one shot and is seated in the next. These two shots do not match because we haven't seen the character sit down. If we saw her sit down in the first shot and then saw her seated in the second, the two shots would be continuous. The critical factor here is using shots that match the action from one shot to the next.

PROVIDING ADEQUATE COVERAGE

PROVIDING ADEQUATE COVERAGE

Directors who do their work properly provide their editors with a variety of shots from which to choose. For example, if one shot features a character in repose, a close shot of the character as well as a long shot will be filmed. If need be, the props in the shot will be moved to ensure that the close shot looks like the long one. The background and the lighting must support the continuity.

Similarly, if an action occurs in a shot, a long shot will be taken of the entire action, and later a close shot will be taken of an important aspect of the action. Some directors film the entire action in long shot, midshot, and close-up so that the editor has maximum flexibility in putting the scene together. Close-ups and cutaways complete the widest possible coverage of the scene.

If the scene includes dialogue between two people, the scene will be shot entirely from one character's point of view and then repeated from the other's point of view. Close-ups of important pieces of dialogue and closeup reaction shots will also be filmed. This is the standard procedure for all but the most courageous or foolhardy directors. This approach provides the editor with all of the footage needed to create continuity.

Finally, considerations of camera angles and camera movement dictate a different series of shots to provide continuity. With camera angles, the critical issue is the placement of the camera in relation to the character's eye level. If two characters are photographed in conversation using a very high angle, as if one character is looking down on the other, the reverseangle shot—the shot from the other character's point of view—must be taken from a low angle. Without this attention to the camera angle, the sequence of shots will not appear continuous. When a film cuts from a high-angle shot to an eye-level reaction shot, viewers get the idea that there is a third person lurking somewhere, as represented by the eye-level shot. When that third person does not appear, the film is in trouble.

MATCHING ACTION

MATCHING ACTION

To provide cut points within shots, directors often ask performers to introduce body language or vocalization within shots. The straightening of a tie and the clearing of a throat are natural points to cut from long shot to close-up when there is no physical movement within the frame to provide the cut point.

Where movement is involved, “here-to-there” is a trick directors use to avoid filming an entire action. When an actor approaches a door, he puts his hand on the doorknob; when he greets someone, he offers his hand. These actions provide natural cut points to move from long shot to close-up. A favorite here-to-there trick is raising a glass to propose a toast. Any action that offers a distinct movement or gesture provides an opportunity within a shot for a cut. The more motion that occurs within the frame, the greater the opportunity for cutting to the next shot.

It is critical that the movement in a shot be distinct enough or important enough so that the cut can be unobtrusive. If the move is too subtle or faint, the cut can backfire. A cut is a promise of more information or more dramatic insight to come. If the second shot is not important, viewers realize that the editor and director have misled them.

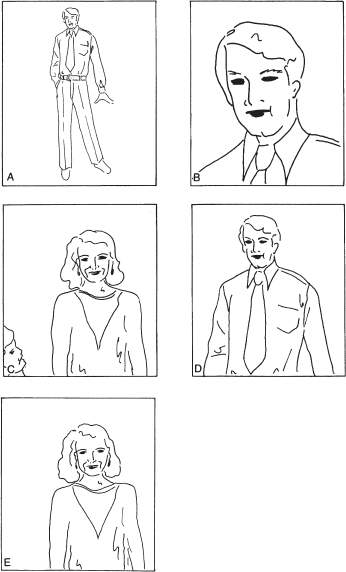

Match cuts, then, are based on (1) visual continuity, (2) significance, and (3) similarity in angle or direction. A sample pattern for a match cut is shown in Figure 25.1. The first cut, from the long shot to the close-up, would be continuous because character 1 continues speaking in the close-up. The next shot is a reverse-angle reaction shot of character 2 from her point of view. After the reverse-angle shot of character 2, we return to a midshot of character 1, and in the final shot, we have a midshot of character 2 speaking. The cuts in this sequence come at points when conversation begins, and the cutting then follows the conversation to show the speaker.

Figure 25.1 |

Sample pattern for a match cut. (A) Long shot of character 1. (B) Close-up of character 1. (C) Reaction shot of character 2; includes character 1 in profile. (D) Midshot of character 1. (E) Midshot of character 2. |

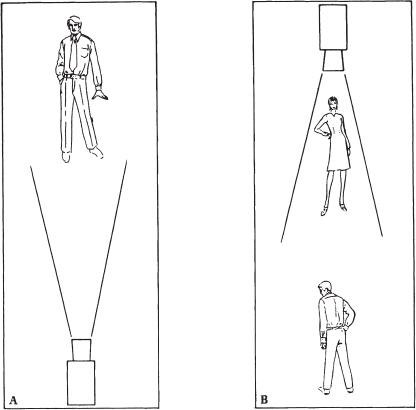

The camera position used to film this sequence must not cause confusion. The straightforward approach, in which character 1 is photographed at a 90-degree angle, is easiest. The reverse-angle shot of character 2 would also be a 90-degree angle (Figure 25.2). If the angle for the reverse shot is not 90 degrees (head on), but rather is slightly angled, it will not appear continuous with the 90-degree shot of character 1. Strict continuity is only possible when the angle of the first shot is directly related to the angle of the next shot. Without this kind of correlation, continuity is broken.

Figure 25.2 |

Positioning the camera for a match cut. To photograph character 1, the camera is placed in front of him, as shown in (A). To photograph the reverse-angle shot of character 2 so that shots 1 and 2 match, the camera is positioned behind character 1, as shown in (B). |

PRESERVING SCREEN DIRECTION

PRESERVING SCREEN DIRECTION

Narrative continuity requires that the sense of direction be maintained. In most chase sequences, the heroes seem to occupy one side of the screen, and the villains occupy the other. They approach one another from opposite directions. Only when they come together in battle do they appear in the same frame.

Maintaining screen direction is critical if the film is to avoid confusion and keep the characters distinct. A strict left-to-right or right-to-left pattern must be maintained. When a character goes out to buy groceries, he may leave his house heading toward the right side of the frame. He gets into his car and begins the journey. If he exited to the right, he must travel left to right until he gets to the store. Reversing the direction will confuse viewers and suggest that the character is lost. Preserving this sense of direction is particularly important when a scene has more than one character. If one character is following another, the same directional pattern will work fine, but if they are coming from two different directions and will meet at a central location, a separate direction must be maintained for each character.

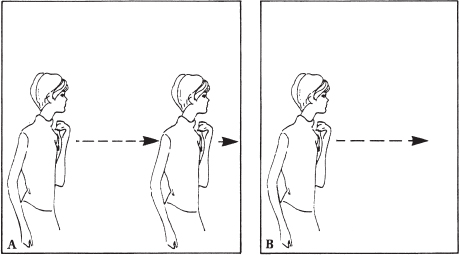

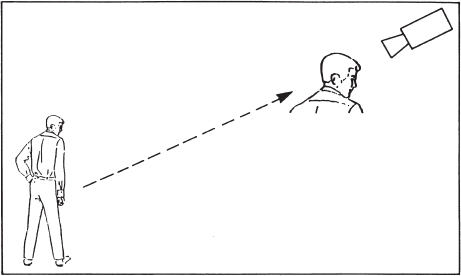

If a character is moving right to left, he exits shot 1 frame right and enters shot 2 frame left (Figure 25.3). The cut point occurs at the instant when the character exits shot 1 and enters shot 2. The match cut preserves continuity and appears to be a single, continuous shot. If there is a delay in the cut between when the character exits shot 1 and when he reappears in shot 2, discontinuity results, or the cut suggests that something has happened to the character. A sound effect or a piece of dialogue would be necessary to explain the delay.

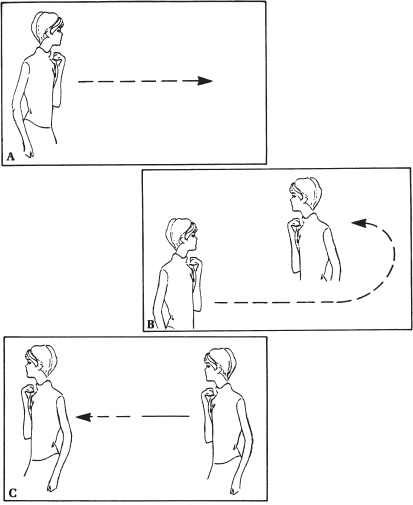

Equally as interesting an issue for the editor is whether to show every shot in the sequence with the character moving across the frame in each shot. Editors often dissolve one shot into another to suggest that the character has covered some distance. Dissolves suggest the passage of time. Another approach, which was used by Akira Kurosawa in The Seven Samurai (1954) and Stanley Kubrick in Paths of Glory (1957), is to show the character in tight close-up with a panning, trucking, or zoom shot that follows the character. As long as the direction in this shot matches that of the full shot of the character, this approach can obviate the need to follow a character completely across the frame. Cutaways and the crosscutting of a parallel action can also be used to avoid continuous movement shots. If a character changes direction, that change must appear in the shot. Once the change is shown, the character can move in the opposite direction. The proper technique is illustrated in Figure 25.4.

Figure 25.3 |

Maintaining screen direction for the match cut. If a character exits frame right (A), she must enter the next shot frame left (B). |

These general rules are applicable whether the shots are filmed with the camera placed objectively or with it angled. Movement need not occur only from left to right or right to left. Diagonal movement is also possible. The character might enter at the bottom left corner of the frame and exit at the upper right corner. Here, the left-to-right motion is preserved. Filmmakers often use this camera position because it provides a variety of options. There is a natural cut point as the character begins to move away from a point very close to the camera. In this classic shot, we see the character's back full frame, and as she walks away from the camera, she comes fully into view. The shot starts as a close-up and ends as a long shot. The director can also choose to follow the character with a subjective camera, or the director can use a zoom to stay with the close-up as the character moves through the frame. In all of these cases, diagonal movement across the frame provides more screen time than left-to-right or right-to-left movement. This makes the shot economically more viable, more interesting, and, because it's subjective, more involving. The shot lasts longer on screen, thereby implying more time has passed. Also the costs of production are so great that a shot that is held on screen longer is better from a production cost point of view.

A shot with diagonal movement that starts as a long shot and ends as a close-up is also involving, and it allows the most literal rendering of the movement (Figure 25.5). An alternative would be to follow the actor's movement with the camera or zoom, maintaining a midshot or close-up throughout the shot. Any of these options will work as long as screen direction is preserved from shot to shot and continuity is maintained.

Figure 25.4 |

Maintaining continuity with a change in direction. (A) Character moves left to right. (B) Character is shown changing direction. (C) Character moves right to left. |

SETTING THE SCENE

SETTING THE SCENE

Match cutting and directional cutting help the editor preserve continuity. The establishing shot, whether it is an extreme long shot or long shot that sets the scene in context, is another important tool. Karel Reisz refers to the scene in Louisiana Story (1948) that begins in a close-up. The setting for the sequence is not established until later.4 What about stories that take place in New York or on Alcatraz or in a shopping mall? In each case, an establishing shot of the location sets the context for the scene and provides a point of reference for the close-ups, the follow action shots, and the visual details of the location.

Figure 25.5 |

Following diagonal movement. The shot shown begins as a long shot and ends as a close shot. |

Most filmmakers use an extreme long shot or a long shot to open the scene. It provides a context for the scene and allows the filmmaker to explore the details of the shot. The classic progression into and out of a scene (long shot/midshot/close-up/midshot/long shot) relies on the establishing shot. The other shots flow out of the establishing shot, and thus a clear continuity is provided. Classically, the establishing shot is the last shot in the scene as well as the first. Many filmmakers and editors have found ways to shorten the regimentation of this approach. Mike Nichols, for example, presented an entire dialogue scene in one shot. By using the zoom lens, he avoided editing. Notwithstanding novel approaches of this type, it is important that editors know how to use the establishing shot to provide continuity for the scene.

MATCHING TONE

MATCHING TONE

Variations in light and color from shot to shot can break continuity. These elements are under the cameraperson's control, but when variations do exist between shots, they can be particularly problematic for the editor.

Laboratory techniques can solve some minor problems, but there are limits to what is possible. Newer, more forgiving film stocks have improved the latitude by overcoming poor lighting conditions and lessened the severity of the problem. The best solution, however, is consistency of lighting, cameraperson, and the sensitivity of the director to that working relationship. If all else fails, it may be necessary to reshoot the affected scenes. This requires the flexibility and understanding of the film's producers.

The editor's goal is always to match the tone between shots, but the editor's ability to find solutions to variations caused by poor lighting control is limited.

MATCHING FLOW OVER A CUT

MATCHING FLOW OVER A CUT

What is the best way to show action without making the continuity appear to be mechanical? Every action has a visual component that can be disassembled into its various parts. Having breakfast may mean removing the food from the refrigerator, preparing the meal, laying out the dishes, eating, and cleaning up. If a scene calls for a character to eat breakfast, all of these sundry elements would add up to some rather elaborate action that is probably irrelevant to the scene's dramatic intention.

To edit the sequence, the editor will have to decide two things: (1) which visual information is dramatically interesting, and (2) which visual information is dramatically necessary. The length of the scene will be determined by the answer to these two questions, particularly the latter. Dramatic criteria must be applied to the selection of shots. If a shot does not help to tell the story, why has it been included in the film?

For example, if it is important to illustrate the fastidious nature of the character, how that character goes about preparing breakfast, eating, and cleaning up might be important. If the character is a slob and that is the important point to be made, then here too the various elements of the breakfast might be shown. However, if it is only important to show how quickly the character must leave home in the morning, the breakfast shots will get short shrift. The dramatic goals, first and foremost, dictate the selection of shots.

Once shots are selected, the mechanical problem for the editor is to make the cuts in such a way that undue time is not spent on shots that provide little information. Is there a way to show the character eating breakfast quickly? The answer, of course, is yes, but the editor does not accomplish this goal by stringing together shots of the character involved in each element of the activity. The screen time required for all of these shots would give the impression of the slowest breakfast ever eaten.

The editor has to find elegant ways to collapse the footage so that the scene requires a minimum of screen time. The shots of the breakfast, for example, can be cut down to a fraction of their previous length, and the scene can be made to flow smoothly and quickly. Consider a shot in which the character enters the kitchen, approaches the refrigerator, removes the milk and juice, and places them on the counter. It is not necessary to watch him traverse the kitchen. By cutting the long shot when he still has some distance to go, moving to a close shot of the refrigerator, holding for a second, and then showing his hand enter the frame to open the refrigerator door, we have collapsed the shot into a fragment of its original length. If the shot that follows this shows the character placing the milk and juice on the counter, we can drop the part of the previous shot where he removes the milk and juice from the fridge and carries them to the counter.

In this hypothetical example, we used a fragment of a shot to make the same point as the entire shot, using considerably less screen time as a result. By applying this approach to all of the shots in the breakfast scene, the vital information will be shown, and the screen time will suggest that the character is having a very quick breakfast. Continuity and dramatic goals are respected when the editor cuts each shot down to its essence. The flow from shot to shot is maintained without mechanically constructing the scene in the most literal sense of the shots. Literal shots do not necessarily provide dramatic solutions.

CHANGE IN LOCATION

CHANGE IN LOCATION

This principle of cutting each shot down to its essence can be applied to show a character changing location. Rather than show the character move from point A to point B, the editor often shows her departing. If she is traveling by car, some detail about the geography of the area is appropriate. Unless there is a dramatic point to the scene other than getting the character from point A to point B, the editor then cuts to a street sign or some other indication of the new location. If the character traveled from left to right, the street sign will be positioned toward the right of the frame. Directors often use a tight close-up here. After holding a few seconds on the close-up, the character enters from frame left, and the zoom back picks up her arrival. If the shot is not a zoom, the character crosses the frame until she stops at the destination within the frame. With these few shots, the audience accepts that the character has traveled from one location to another, and little screen time was required to show that change in location.

CHANGE IN SCENE

CHANGE IN SCENE

To alert the audience to a change in scene, it is important to provide some visual link between the last shot of one scene and the first shot of the next. Many directors and editors now cover this transition with a shift in sound or by running the same sound over both shots. However, this inexpensive method shouldn't dissuade you from trying to find a visual solution.

If there is a similarity in movement from one shot to another, visual continuity can be achieved. This works by tracking slowly in the last shot of the first scene from left to right or from right to left. Because the movement is slow, the details are visible. The cut usually occurs when the tracking shot reaches the middle of the frame. In the next scene, the movement is picked up at about the same point in midframe, but as the motion is completed, it becomes clear that a new scene is beginning.

A change in scene can also be effected by following a particular character. If he appears in a suit in the last shot of one scene and in shorts in the first shot of the next scene, the shift occurs smoothly. Other elements help ease the transition, for example, the character might be speaking at the end of the first scene and at the beginning of the next.

Finally, a straightforward visual cue, such as a prop, can be used to make the transition. Suppose, for instance, that one scene ends with a close-up of a marvelous antique lamp. If the next scene begins with a close-up of another antique lamp and pulls back to reveal an antique store, the shift will be effective. The visual link between scenes allows a smooth transition to take place. The scenes may have very little to do with one another, but they will appear to be continuous.