26 |

The Picture Edit and Pace |

||

Once the rough assembly is satisfactory, the question of narrative clarity has, to a certain extent, been satisfied. Shots flow from one to another and suggest continuity. What is still lacking is the dramatic emphasis of one shot relative to another. This is the role of pace, which is fine-tuned in the second editing stage. The product of this stage, the fine cut, is the culmination of all of the editor's decisions. At the end of the fine cut, the choices have all been made, and the sound tracks have been aligned and prepared for the mix. The stage between rough cut and final sound mix is the subject of this chapter. The goal of this stage is to introduce dramatic impact through the editing decisions.

Pace is most obvious in action sequences, but all sequences are shaped for dramatic effect. Variation in pace guides viewers in their emotional response to the film. More rapid pacing suggests intensity; slower pacing, the reverse.

Karel Reisz explores the opposite of editing for pace in his discussion of Hitchcock's Rope (1948), a film that was directed to avoid editing.1 The entire film looks like a single long take. Reisz argues that too much screen time, which could have been used more productively, is wasted moving the camera from one spot to another.

This notion may seem obvious, but when we look at the opening of Welles's Touch of Evil (1958), we may back away from too general a statement about using camera movement to avoid editing. This 3-minute sequence follows a car from a scene in which a bomb is planted in its trunk to a scene showing the owner returning with a guest to a scene in which they drive from Tijuana across the border into California. During the drive, we see Varguez (Chariton Heston), a Mexican policeman, cross the border with his new wife (Janet Leigh). They occupy the foreground while the doomed car moves across the border in the background. Soon after, the car passes them and explodes. The explosion leads to the first cut in the film.

Welles chose to begin his film with an elegant tracking shot through town and across the border. He could have fragmented the scene into shots that showed the bomb being planted and the owner returning and intercut the car with Varguez as each progressed across the border. If he had taken this approach, the pacing would have progressively quickened as we moved toward the explosion. The pace, rather than the contradiction between foreground and background, would have heightened the tension of the film.

In Touch of Evil, Welles avoided editing, avoided the pacing, and yet opened the film with a mesmerizing and powerful sequence. This example suggests that pace isn't everything. It reminds us that composition, lighting, and performance also count.

Having suggested the limits of pace, let's turn now to the possibilities of pace. Many directors specializing in political thrillers have used pace to empower their message. Costa-Gavras's exposé of Greek injustice in Z (1969) and Oliver Stone's exploration of political assassination in JFK (1991) both rely on juxtaposition and pace to drive home a particular point of view.

Another genre in which pace plays a central role is the adventure film. In both the mixed genre adventure film, such as Joel Coen's Raising Arizona (1987), and the straightforward adventure film, such as Steven Spielberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), pace helps provide the sense of energy and excitement that is at the heart of the genre's success.

Whether it is the excitement of an adventure film or the indignation of a political thriller, pace is the key. The role of pace varies in different genres, but it always comes into play to some degree.

TIMING

TIMING

One element of pace is the timing of particular shots. Where in a sequence should a particular close-up or cutaway be positioned for maximum impact? When is a subjective shot more powerful than an objective one? What is the most effective pattern of crosscutting between shots or juxtapositions within shots? These are editing decisions that directly affect the issue of dramatic effectiveness.

The editor's understanding of the purpose of the sequence as a whole helps her make these decisions. The purpose of the sequence might be exposition or characterization. Within these broad categories, the editor must decide how much visual and aural explanation and how much punctuation are needed to make the point. Finally, she must decide whether to take a straightforward editing strategy or use its alternative: a more indirect, layered strategy. For example, in a comedy film, the strategy of editing for surprise might be most appropriate. In comedy, surprise is critical. If the edit is not properly timed, the comedy is lost. Surprise is also useful in the thriller. In most other genres, though, a more straightforward approach is generally taken.

An example of surprise used for comic purposes can be found in Joel Coen's Raising Arizona. A 6-minute comedy sequence is difficult to sustain, particularly if it is an action sequence, but it succeeds in Raising Arizona. In the film. Hi (Nicholas Cage) and Ed (Holly Hunter), a childless couple, have stolen a baby from a rich businessman whose wife has had quintuplets. Hi is a former criminal, and Ed is a former law-enforcement officer. In this sequence, Hi decides to revert to crime in his old milieu, the local convenience store. Ed is not happy about this decision. Not only would Hi be breaking the law, but if caught, his actions would deprive their new child of its “father.”

The sequence begins with Hi and Ed expressing concern about the future. They stop at a convenience store to buy disposable diapers for the baby. Ed plays with the baby while Hi enters the store. The first surprise comes when Hi decides to rob the store of a box of diapers and as much cash as he can get. The clerk pushes a silent alarm.

The next surprise is Ed's response once she sees Hi robbing the store. She becomes angry and leaves, deserting him. Hi is surprised by Ed's action, but not as surprised as he is by the store clerk, who has now a Magnum .357 in his hand and is trying to kill him. Hi flees on foot, but the police sirens suggest he is in trouble. He runs after Ed, with the police cars in pursuit.

Hi escapes into a backyard, only to be accosted by a watchdog. The dog lunges, but it is chained to an anchor, which saves Hi's life. Hi continues to run, but the dog is persistent and pulls the chain's anchor from the ground. The dog joins the police and the clerk in their pursuit of Hi. At this point, Ed, who has gotten over her anger, returns to pick up Hi, but she can't find him. Hi, now desperate, stops a truck on the road. He threatens the driver, who takes him into the truck.

Other neighborhood dogs take off after Hi, who is now being chased by dogs, the police, a store clerk, and his wife. The clerk fires his gun and shatters the truck's windshield. As the driver turns to avoid the onslaught, the first dog jumps the armed clerk by mistake. To avoid the police, the truck driver changes direction, putting the truck on a collision course with a house.

The truck driver, terrified by threats approaching from all sides, puts on the brakes. The sudden stop sends Hi flying through the front of the truck. The truck driver backs up and escapes. Meanwhile, Hi has been deposited on the front steps of a house. He runs through the house, closely pursued by the police and the dogs.

He escapes into a supermarket, where he picks up another box of diapers (he lost the other package). The police and the dogs are still in pursuit, and now the supermarket manager begins firing at Hi with a shotgun. The panicking customers add to the chaos, and Hi escapes. He loses the second box of diapers, but he is picked up by Ed outside the supermarket. They escape.

In this sequence, the timing of the surprises—the clerk's gun, the dog's tenacity, the truck driver's panic—all depend on the editing of the scene. In each case, a quick cut introduces the surprise, often in an exaggerated visual. The clerk's Magnum, for example, seems like a cannon due to its proximity to the camera and the use of a wide-angle lens. The quick cut and the visual exaggeration yield the desired comic effect.

RHYTHM

RHYTHM

In general, the rhythm of a film seems to be an individual and intuitive matter. We know when a film does not have a rhythm. The jerkiness of the editing draws attention to itself. When the film has an appropriate rhythm, the editing appears to be seamless, and we become totally involved with the characters and the story. Of course, intuition alone is not enough. Some practical considerations help determine an appropriate length for particular shots within a sequence.

The amount of visual information within the shot often determines the length of the shot. A long shot, which has more visual information than a close-up, will be held for a longer time to allow the audience to absorb the information. If the information is new, it is appropriate to allow the shot to run longer so that the audience can become familiar with the new milieu. Moving shots are often held on screen longer than static images to allow the audience to absorb the shifting visual information. A cutaway that is important to the plot is generally extended to establish its importance.

Conversely, a close-up with relatively little information will be held on screen for only a short time. The same is true for static shots and repeated shots. Once the shot's visual information has been viewed, it's not necessary to give equal time to a second or third viewing.

It's not possible to provide absolute guidelines about the length of shots. However, it is important that the editor develop a sense of the relative lengths of shots within a sequence. Shots should never be all the same length. If they are all long or all short, the lack of variety deadens the impact of the sequence. It will have no rhythm. In the pacing of shots, rhythm requires the variation of the length of the shots.

Rhythm is also affected by the type of transition used between sequences. A straight cut can be jarring; it leaves us confused until a sound or visual cue suggests that a change has taken place. A dissolve at the end of one sequence into the beginning of the next makes a smooth transition and provides a visual cue. The dissolve, which is often associated with the passing of time, can also imply a change of location. The rhythm between sequences is smoother when dissolves are used.

A fade-out is occasionally used at the end of a sequence. Although it is clearly indicative of the closure of one sequence and the beginning of the next, the fade is currently not as widely used as it once was. It is still more popular than the wipe or iris shot, but it is certainly less popular than the dissolve.

If the editor's goal is to make a sequence seamless, his first criterion is to understand and work to clarify the emotional character of the scene. To do so most effectively, the editor must respect the emotional structure of the performances. This means trusting that a pause between two lines of dialogue is not necessarily a lapse, but rather part of the construct of the performance. To edit out the pause may make superficial sense, but makes no sense whatsoever in terms of the performance. The editor must learn to distinguish performance from error, or dead space. It may be as simple as following action to its conclusion, or it may be more complex, involving the subtle nuances of the delivery of dialogue or nonverbal mannerisms. Cutting into the performance may break the rhythm established by the performer in the scene or sequence.

Understanding both the narrative and the subtextual goals of a scene will also allow the editor to follow and modulate the editing so that it clarifies and emphasizes rather than confuses. The editor will be able to determine how long the shots need to be held on screen and how much modulation is necessary to make the point of the scene clear. The editor will then be able to use the most dynamic tools, like crosscutting, and the most minimal, the long shot, for maximum effect.

A simplified example of rhythmic pacing can be found in the “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” sequence in Bob Fosse's Cabaret (1972). A young boy stands up in a rural beer garden in 1932 Germany. He is dressed in a Hitler Youth uniform, but he is young enough to have an innocent, prepubescent voice. The impression he gives is of youthful beauty and optimism. As the song progresses, the orchestration becomes more elaborate, and the young man is joined by others. By the end of the song, Germans of all ages have joined in a defiant interpretation of the lyrics. By editing rapidly, using many closeups, and cutting to Germans of all ages, Fosse produced a powerful sequence foreshadowing Nazism. The editing helps create the feelings of both innocence and aggression as the singers shift from a simple, innocent interpretation of the song to an aggressive one. The shifting emotional tone of the scene is modulated, and the result illustrates not only the power of pacing, but also how the modulation of pace enhances the power of a scene.

A more subtle and complex example is the 9-minute sequence that serves as the dramatic climax of Bernardo Bertolucci's The Conformist (1971). Marcello (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is an upper-middle-class follower of Mussolini in pre-World War II Italy. He wants to be accepted by the Fascists, but at his initiation, they ask him to help in assassinating an exiled dissident in Paris. The man is Marcello's former professor. On his honeymoon in Paris, Marcello reestablishes contact with Professor Quadri and gains his trust. He also falls in love with the professor's young wife, Anna (Dominique Sanda). He warns her not to accompany her husband on his trip, but at the last minute, she chooses to travel with him.

The assassination sequence that follows reveals Marcello's true nature as a coward and facism's true nature as a brutal ideology that does not tolerate dissidence. The sequence can be broken down into five sections plus a prologue: prologue (2 minutes, 45 seconds), (1) the trap (2 minutes), (2) the murder of the professor (1 minute, 25 seconds), (3) Anna's attempt to be saved (1 minute), (4) Bangangan's response (40 seconds), and (5) the murder of Anna (1 minute, 30 seconds).

Given the extreme dramatic nature of the events, Bertolucci did not rely on rapid pace. Instead, he varied the shots between subjective close-ups and objective traveling shots. Only in the last sequence, the murder of Anna, did he use subjective camera movement. Bertolucci also varied foreground and background. The long shots are wide-angle shots of the fog- and snow-shrouded road through the forest. The early morning light throws shadows that are as stately as the trees of the forest. In the close-ups, Bertolucci used a telephoto lens that collapsed and blurred the context. The close-ups are interior shots in Marcello's car or in Professor Quadri and Anna's car. By varying close-ups, long shots, and point-of-view shots, Bertolucci set up a visual tension that is every bit as powerful as if he had relied on pace alone.

In the first scene in the sequence, Marcello muses about Quadri and Anna. He wishes he were not there. His driver, Bangangan, is a Fascist to the core. He has no dreams, only memories of his induction into the ideology that organizes his interior and exterior lives. The reverie of this scene was created with very lengthy takes, including a 50-second close-up of Marcello. In this shot, Bertolucci dropped the focus and slowly panned to Bangangan, also in close-up. Bertolucci avoided editing the interior car shots to create a greater sense of unity inside the car. He alternated the interiors with wide-angle objective tracking shots of the car moving through the forest. The result is a highly emotional stylization. The scene has an emotional reality but seems almost too beautiful to be real.

The next shot shifts to the interior of Quadri's car. Anna and Quadri appear in a crowded close-up. The subjective point of view shows the road ahead as Anna looks back and tells Quadri that she thinks they are being followed. He dismisses the idea. Anna's sense of the danger ahead is offset by his assurance that he sees nothing.

The scene proceeds in a very stylized manner to show their car cut off by a feigned accident in front of them and Marcello's car stopped behind them. Close-ups of each statically present the stand-off that precedes the murder. Only Quadri's insistence on seeing to the well-being of the other driver breaks the stillness. Anna asks him not to go. He finds the driver unconscious and the car locked. Anna locks her car. The static shots stretch out the sequence, which is long at 2 minutes. This pause is emotionally tense because we see the scene through Marcello's eyes. He knows what is coming. Although the scene is more rapidly cut than the prologue, it is nevertheless slowly paced.

The murder of Quadri is cut much faster. The killers come from the woods. They are joined by the driver of the front car. The killing itself is presented as a version of the killing of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. All of the killers participate. They use knives, and the death is drawn out. Because of the nature of the content, this scene is more rapidly paced than the previous scenes in this sequence.

The next scene, Anna's attempt to save herself, relies less on pace than on performance and close-ups. The pain and poignancy of Anna screaming for Marcello to save her is accentuated by their relationship and by the situation. She pulls on the door of his car, facing him, screaming for her life. His inability or unwillingness to help her represents the emotional high point of the sequence. This is Marcello's moment of truth, his opportunity for salvation, but it is not to be. Love is not great enough to overcome politics. He does not rescue her, and she runs off to her fate. The shots in this scene are held much longer than the shots of the preceding murder scene.

The next scene is short. Bangangan editorializes on his disdain for Marcello and categorizes him with every other group that the Fascists hate. This scene is not very long, but it provides an opportunity to pause between the two most powerful scenes in the sequence. It allows the audience to recover somewhat from the shock of Marcello's failure to save Anna.

The final sequence, the murder of Anna, does not rely on pace, although it is one of the most powerful scenes in the film. Instead, Bertolucci used subjective camera footage of the murderers as they chase Anna through the woods. The camera is handheld, and consequently, the action seems all the more real. The Fascists fire at her, passing the automatic pistol to one another. She is shot, falters, and then falls. The camera moves unsteadily around her bloodied body, and even after her death, it continues to circle before finally retreating from the woods with the killers. The shifts in pace in this scene have more to do with the pace of the movement itself than with the editing. That movement slows once Anna has been shot and continues at a slower pace until the end of the sequence.

This sequence uses a varied pace to carry us through a wide range of emotions. It also identifies a clear emotional role for each of the characters. In fact, Bertolucci remained very close to those roles through his use of close-ups. By varying the close-ups with objective long shots of the forest, Bertolucci added a layer of tension that supported the pace when he chose to rely on it.

This entire sequence is 9 minutes long on the screen. To the extent that we are involved in the sequence, we suspend our sense of real time. In real time, the sequence might have taken 5 minutes or 5 hours. Certain parts of the sequence are given more time than might have been expected. Anna's plea for help, for example, is as long as each murder. Realistically, it would not have taken so long given the proximity of the murderers. However, Bertolucci felt that it was important to give Marcello a chance for redemption and a chance to be incapable of it. This, as much as the loss of a woman he loves, is Marcello's tragedy. The length of Anna's plea for help is thus dramatically important. Pace is affected by the importance of the scene to the film. If the scene is sufficiently important, it may be extended to suit its dramatic importance to the story.

TIME AND PLACE

TIME AND PLACE

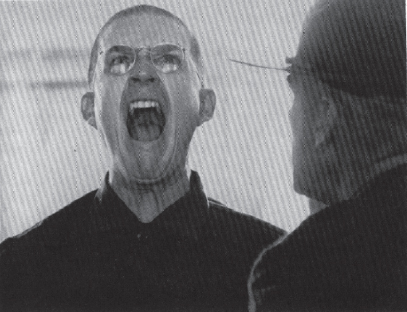

Pace can help establish a sense of time and place. Examples from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Barry Lyndon (1975) were discussed in Chapter 10. Kubrick exploited pace to the same extent in the battle for Hue in Full Metal Jacket (1987) (Figure 26.1) as he did in his earlier works. The pace of the sequences, the cinema verité camera style, the set design, and the sound create the setting of Hue, Vietnam, in 1968. The actual city was re-created on a set in England for the film. Martin Scorsese relied heavily on pace to help him create his version of New York in Mean Streets (1973), and George Lucas relied on music and pace to create his view of Northern California in the early 1960s in American Graffiti (1973).

Figure 26.1 |

Full Metal Jacket, 1987. Courtesy of British Film Institute. |

Few filmmakers have been more effective at using pace to create a sense of time and place than Carroll Ballard was in The Black Stallion (1979). The first 45 minutes of the film are largely silent. The first third of the film tells the story of young Alec, who is on a ship near the coast of North Africa. The year is 1946. Alec becomes fond of a black horse on board the ship. It is an Arabian, untamed and seemingly untameable. The ship encounters bad weather, and a fire on board threatens the passengers’ lives. Alec's father saves his life, and the boy saves the horse's life.

For the next 30 minutes, the scene shifts to a deserted island where the boy and the horse, seemingly the only survivors of a shipwreck, become friends and in so doing, save each other. Two primary locations are featured in this section of the film: the ship and the island. Ballard realized that he had to create both from the perspective of an inquisitive 11-year-old child. He did this with a magical realism. The images are almost other-worldly, and the editing recognizes Alec's sense of the importance of particular details about the horse, his father, and the world. He is not afraid of the world; rather, he is part of it.

Time is collapsed for all but the important events. We know that much real time has passed, and we accept the mundane details of life on the island: food, shelter, and warmth. Alec's relationship with the horse, which is carefully developed in the sequence, is detailed in almost a magical progression. The boy gains the horse's trust by offering him food and later takes him into the water where he gradually mounts the horse. The magical character of this part of the film is enhanced by shots of the boy and the horse from the perspective of the sandy ocean bottom. They appear as intruders, and somehow it unifies them in the context of the mysterious sea. Ballard alternated this sequence with traveling shots of boy and horse filmed from high above the water. The effect is to reinforce the specificity of the time and place.

THE POSSIBILITIES OF RANDOMNESS UPON PACE

THE POSSIBILITIES OF RANDOMNESS UPON PACE

One of the remarkable elements of editing is that the juxtaposition of any grouping of shots implies meaning. The pacing of those shots suggests the interpretation of that meaning. The consequence of this is seen in microcosm when a random shot or cutaway is edited into a scene: it introduces a new idea. This principle is elaborated where there are a number of random shots in a scene. If edited for effect, the combination of shots creates a meaning quite distinct from the sum of the individual parts. This shaping is, in effect, pure editing.

A specific example suggests the possibilities. Francesco Rosi's Three Brothers (1980) opens with an image of an artificial building—a parody of a building suitable to a dream—in the background and a group of large rats in the foreground. The rats approach the camera. The cut to the next shot, a close-up of a young man asleep, suggests that he is dreaming of the rats. The scene that follows shows that he lives and works in an institution for juveniles. Was he dreaming that his wards are rats or that the other members of society are? The two opening shots are set into context by the scene that follows, but the juxtaposition implies potential meanings beyond the content of either shot.

In Ingmar Bergman's Winter Light (1962), a disillusioned minister serves a small parish. One man has lost his faith and contemplates suicide. Others want to relate to the minister, but he is unable to relate to them. Bergman used juxtapositions to detail the minister's disillusionment. A series of exterior dissolves at the end of the sermon imply his distance from the parishioners. Later, a parishioner who wants to take care of him (the minister's wife has died) has left him a letter. He reads the letter, which explains how she feels about him. Bergman cut from his reading the letter to the woman in midshot confessing her feelings. By cutting in that second shot, Bergman moved us from the minister's dispassion and indifference to the parishioner's passion. He altered the meaning of one shot by shifting to another. The shots don't necessarily provide continuity; the contradiction between the shots alters the meaning of the scene.

The films of Rosi and Bergman suggest how the juxtaposition and organization of shots can layer meaning. The pacing of the shots themselves deepens the effect of juxtaposing random shots.

NOTE/REFERENCE

NOTE/REFERENCE

| 1. | Karel Reisz and Gavin Millar, The Technique of Film Editing (Boston: Focal Press, 1968), 233–236. |