| 1 |

The Silent Period |

||

Film dates from 1895. When the first motion pictures were created, editing did not exist. The novelty of seeing a moving image was such that not even a screen story was necessary. The earliest films were less than a minute in length. They could be as simple as La Sortie de I'Usine Lumière (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory) (1895) or Arrivée d'un Train en Gare (Arrival of a Train at the Station) (1895). One of the more popular films in New York was The Kiss (1896). Its success encouraged more films in a similar vein: A Boxing Bout (1896) and Skirt Dance (1896). Although George Méliès began producing more exotic “created” stories in France, such as Cinderella (1899) and A Trip to the Moon (1902), all of the early films shared certain characteristics. Editing was nonexistent or, at best, minimal in the case of Méliès.

What is remarkable about this period is that in 30 short years, the principles of classical editing were developed. In the early years, however, continuity, screen direction, and dramatic emphasis through editing were not even goals. Cameras were placed without thought to compositional or emotional considerations. Lighting was notional (no dramatic intention meant), even for interior scenes. William Dickson used a Black Maria.1 Light, camera placement, and camera movement were not variables in the filmic equation. In the earliest Auguste and Louis Lumière and Thomas Edison films, the camera recorded an event, an act, or an incident. Many of these early films were a single shot.

Although Méliès's films grew to a length of 14 minutes, they remained a series of single shots: tableaus that recorded a performed scene. All of the shots were strung together. The camera was stationary and distant from the action. The physical lengths of the shots were not varied for impact. Performance, not pace, was the prevailing intention. The films were edited to the extent that they consisted of more than one shot, but A Trip to the Moon is no more than a series of amusing shots, each a scene unto itself. The shots tell a story, but not in the manner to which we are accustomed. It was not until the work of Edwin S. Porter that editing became more purposeful.

EDWIN S. PORTER: FILM CONTINUITY BEGINS

EDWIN S. PORTER: FILM CONTINUITY BEGINS

The pivotal year in Porter's work was 1903. In that year, he began to use a visual continuity that made his films more dynamic. Méliès had used theatrical devices and a playful sense of the fantastic to make his films seem more dynamic. Porter, impressed by the length and quality of Méliès's work, discovered that the organization of shots in his films could make his screen stories seem more dynamic. He also discovered that the shot was the basic building block of the film. As Karel Reisz suggests, “Porter had demonstrated that the single shot, recording an incomplete piece of action, is the unit of which films must be constructed and thereby established the basic principle of editing.”2

Porter's The Life of an American Fireman (1903) is made up of 20 shots. The story is simple. Firemen rescue a mother and child from a burning building. Using newsreel footage of a real fire, together with performed interiors, Porter presents the 6-minute story as a view of the victims and their rescuers. In 6 minutes, he shows how the mother and child are saved.

Although there is some contention about the original film,3 a version that circulated for 40 years presents the rescue in the following way. The mother and daughter are trapped inside the burning building. Outside, the firemen race to the rescue. In the version that circulated from 1944 to 1985, the interior scenes were intercut with the newsreel exteriors. This shot-by-shot alternating of interior and exterior made the story of the rescue seem dynamic. The heightened tension from the intercutting was complemented by the inclusion of a close-up of a hand pulling the lever of a fire alarm box.

The inclusion of the newsreel footage lent a sense of authenticity to the film. It also suggested that two shots filmed in different locations, with vastly different original objectives, could, when joined together, mean something greater than the sum of the two parts. The juxtaposition could create a new reality greater than that of each individual shot.

Porter did not pay attention to the physical length of the shots, and all of the shots, excluding that of the hand, are long shots. The camera was placed to record the shot rather than to editorialize on the narrative of the shot.

Porter presented an even more sophisticated narrative in late 1903 with The Great Train Robbery. The film, 12 minutes in length, tells the story of a train robbery and the consequent fate of the robbers. In 14 shots, the film includes interiors of the robbery and exteriors of the attempted getaway and chase. The film ends very dramatically with an outlaw in subjective midshot firing his gun directly toward the audience.

There is no match-cutting between shots, but there are location changes and time changes. How were those time and location changes managed, given that the film relies on straight cuts rather than dissolves and fades, which were developed later?

Every shot presents a scene: the robbery, the getaway, the pursuit, the capture. No single shot in itself records an action from beginning to end. The audience enters or exits a shot midway. Here lies the explanation for the time and location changes. For narrative purposes, it is not necessary to see the shot in its entirety to understand the purpose of the shot. Entering a shot in midstream suggests that time has passed. Exiting the shot before the action is complete and viewing an entirely new shot suggest a change in location. Time and place shifts thus occur, and the narrative remains clear. The overall meaning of the story comes from the collectivity of the shots, with the shifts in time or place implied by the juxtaposition of two shots.

Although The Great Train Robbery is not paced for dramatic impact, a dynamic narrative is clearly presented. Porter's contribution to editing was the arrangement of shots to present a narrative continuity.4

D. W. GRIFFITH: DRAMATIC CONSTRUCTION

D. W. GRIFFITH: DRAMATIC CONSTRUCTION

D. W. Griffith is the acknowledged father of film editing in its modern sense. His influence on the Hollywood mainstream film and on the Russian revolutionary film was immediate. His contributions cover the full range of dramatic construction: the variation of shots for impact, including the extreme long shot, the close-up, the cutaway, and the tracking shot; parallel editing; and variations in pace. All of these are ascribed to Griffith. Porter might have clarified film narrative in his work, but Griffith learned how to make the juxtaposition of shots have a far greater dramatic impact than his predecessor.

Beginning in 1908, Griffith directed hundreds of one- and two-reelers (10- to 20-minute films). For a man who was an unemployed playwright and performer, Griffith was slow to admit more than a temporary association with the new medium. Once he saw its potential, however, he shed his embarrassment, began to use his own name (initially, he directed as “Lawrence Griffith”), and zealously engaged in film production with a sense of experimentation that was more a reflection of his self-confidence than of the potential he saw in the medium. In the melodramatic plot (the rescue of children or women from evil perpetrators), Griffith found a narrative with strong visual potential on which to experiment. Although at best naive in his choice of subject matter,5 Griffith was a man of his time, a nineteenthcentury Southern gentleman with romanticized attitudes about societies and their peoples. To appreciate Griffith's contribution to film, one must set aside content considerations and look to those visual innovations that have made his contribution a lasting one.

Beginning with his attempt to move the camera closer to the action in 1908, Griffith continually experimented with the fragmentation of scenes. In The Greaser's Gauntlet (1908), he cut from a long shot of a hanging tree (a woman has just saved a man from being lynched) to a full body shot of the man thanking the woman. Through the match-cutting of the two shots, the audience enters the scene at an instant of heightened emotion. Not only do we feel what he must feel, but the whole tenor of the scene is more dynamic because of the cut, and the audience is closer to the action taking place on the screen.

Griffith continued his experiments to enhance his audience's emotional involvement with his films. In Enoch Arden (1908), Griffith moved the camera even closer to the action. A wife awaits the return of her husband. The film cuts to a close-up of her face as she broods about his return. The apocryphal stories about Biograph executives panicking that audiences would interpret the close-up as decapitation have displaced the historical importance of this shot. Griffith demonstrated that a scene could be fragmented into long shots, medium shots, and close shots to allow the audience to move gradually into the emotional heart of the scene. This dramatic orchestration has become the standard editing procedure for scenes. In 1908, the effect was shocking and effective. As with all of Griffith's innovations, the close-up was immediately adopted for use by other filmmakers, thus indicating its acceptance by other creators and by audiences.

In the same film, Griffith cut away from a shot of the wife to a shot of her husband far away. Her thoughts then become visually manifest, and Griffith proceeds to a series of intercut shots of wife and husband. The cutaway introduces a new dramatic element into the scene: the husband. This early example of parallel action also suggests Griffith's experimentation with the ordering of shots for dramatic purposes.

In 1909, Griffith carried this idea of parallel action further in The Lonely Villa, a rescue story. Griffith intercuts between a helpless family and the burglars who have invaded their home and the husband who is hurrying home to rescue his family. In this film, Griffith constructed the scenes using shorter and shorter shots to heighten the dramatic impact. The resulting suspense is powerful, and the rescue is cathartic in a dramatically effective way. Intercutting in this way also solved the problem of time. Complete actions needn't be shown to achieve realism. Because of the intercutting, scenes could be fragmented, and only those parts of scenes that were most effective needed to be shown. Dramatic time thus began to replace real time as a criteria for editing decisions.

Other innovations followed. In Ramona (1911), Griffith used an extreme long shot to highlight the epic quality of the land and to show how it provided a heightened dimension to the struggle of the movie's inhabitants. In The Lonedale Operator (1911), he mounted the camera on a moving train. The consequent excitement of these images intercut with images of the captive awaiting rescue by the railroad men again raised the dramatic intensity of the sequence. Finally, Griffith began to experiment with film length. Although famous for his one-reelers, he was increasingly looking for more elaborate narratives. Beginning in late 1911, he began to experiment with two-reelers (20 to 32 minutes), remaking Enoch Arden in that format. After producing three two-reelers in 1912—and spurred on by foreign epics such as the 53-minute La Reine Elizabeth (Queen Elizabeth) (1912) from France and Quo Vadis (1913) from Italy—Griffith set out to produce his long film Judith of Bethulia (1913). With its complex Biblical story and its mix of epic baffles and personal drama, Griffith achieved a level of editing sophistication never before seen on screen.

Griffith's greatest contributions followed. The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916) are both epic productions; each screen story lasts more than two hours. Not only was Griffith moving rapidly beyond his tworeelers, he was now making films more than twice the length of Judith of Bethulia. The achievements of these two films are well documented, but it is worth reiterating some of the qualities that make the films memorable in the history of editing.

Not only was The Birth of a Nation an epic story of the Civil War, but it also attempted in two and one-half hours to tell in melodramatic form the stories of two families: one from the South, and the other from the North. Their fate is the fate of the nation. Historical events such as the assassination of Lincoln are intertwined with the personal stories, culminating in the infamous ride of the Klan to rescue the young Southern woman from the freed slaves. Originally conceived of as a 12-reel film with 1544 separate shots, The Birth of a Nation was a monumental undertaking. In terms of both narrative and emotional quality, the film is astonishing in its complexity and range. Only its racism dates the film.

The Birth of a Nation displays all of the editing devices Griffith had developed in his short films. Much has been written about his set sequences, particularly about the assassination of Lincoln6 and the ride of the Klan. Also notable are the battle scenes and the personal scenes. The Cameron and Stoneman family scenes early in the film are warm and personal in contrast to the formal epic quality of the battle scenes. These disparate elements relate to one another in a narrative sense as a result of Griffith's editing. In the personal scenes, for example, the film cuts away to two cats fighting. One is dark, and the other is light gray. Their fight foreshadows the larger battles that loom between the Yankees (the Blues) and the Confederates (the Grays). The shot is simple, but it is this type of detail that relates one sequence to another.

In Intolerance, Griffith posed for himself an even greater narrative challenge. In the film, four stories of intolerance are interwoven to present a historical perspective. Belshazzar's Babylon, Christ's Jerusalem, Huguenot France, and modern America are the settings for the four tales. Transition between the time periods is provided by a woman, Lillian Gish, who rocks a cradle. The transition implies the passage of time and its constancy. The cradle implies birth and the growth of a person. Cutting back to the cradle reminds us that all four stories are part of the generational history of our species. Time and character transactions abound. Each story has its own dramatic structure leading to the moment of crisis when human behavior will be tested, challenged, and questioned. All of Griffith's tools—the close-ups, the extreme long shots, the moving camera—are used together with pacing. The film is remarkably ambitious and, for the most part, effective.

More complex, more conceptual, and more speculative than his former work, Intolerance was not as successful with audiences. However, it provides a mature insight into the strengths and limitations of editing. The effectiveness of all four stories is undermined in the juxtaposition. The Babylonian story and the modern American story are more fully developed than the others and seem to overwhelm them, particularly the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Huguenot France. At times the audience is confused by so many stories and so many characters serving a metaphorical theme. The film, nevertheless, remains Griffith's greatest achievement in the eyes of many film historians. Because The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance are so often the subject of analysis in film literature, rather than refer to the excellent work of others, the balance of this section focuses on another of Griffith's works, Broken Blossoms (1919).

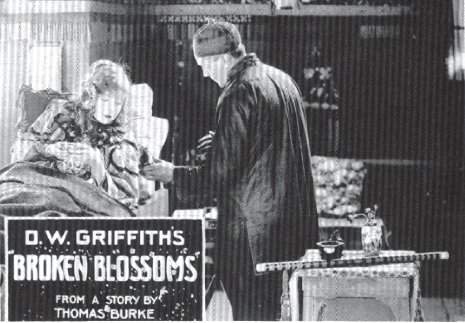

Broken Blossoms is a simple love story set in London. A gentle Chinese man falls in love with a young Caucasian woman. The woman, portrayed by Lillian Gish, is victimized by her brutal father (Donald Crisp), who is aptly named Battler. When he learns that his daughter is seeing an Oriental (Richard Barthelness), his anger explodes, and he kills her. The suitor shoots Battler and then commits suicide. This tragedy of idealized love and familial brutality captures Griffith's bittersweet view of modern life. There is no place for gentleness and purity of spirit, mind, and body in an aggressive, cruel world.

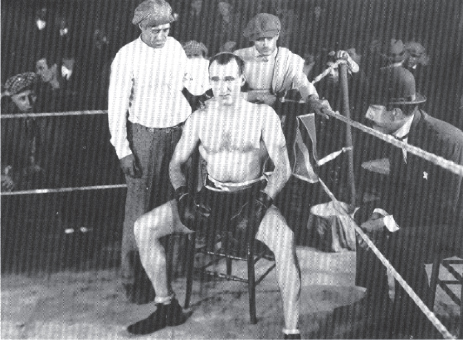

The two cultures—China and Great Britain—meet on the London waterfront and in the opium dens (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). On the waterfront the suitor has set up his shop, and here he brings the young woman (Figures 1.3 and 1.4). Meanwhile, Battler fights in the ring (Figure 1.5). Griffith intercuts the idyllic scene of the suitor attending to the young woman (Figure 1.6) with Battler beating his opponent. The parallel action juxtaposes Griffith's view of two cultures: gentleness and brutality. When Battler finishes off his opponent, he rushes to the suitor's shop. He is led there by a spy who has informed him about the whereabouts of the young woman. Battler destroys the bedroom, dragging the daughter away. The suitor is not present.

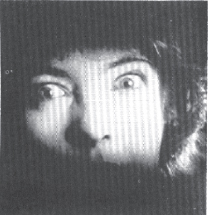

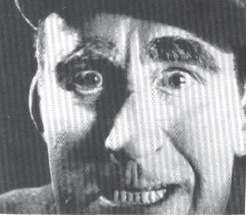

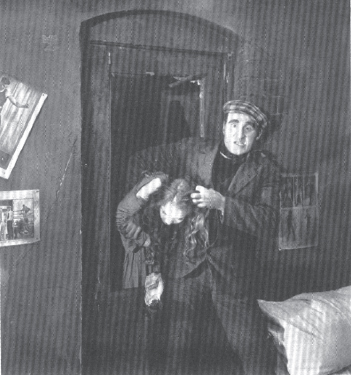

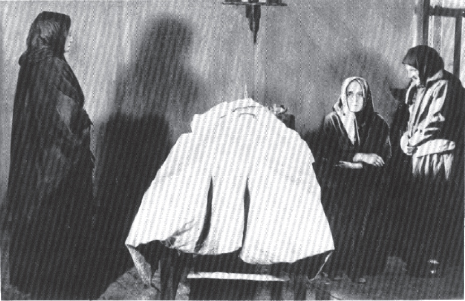

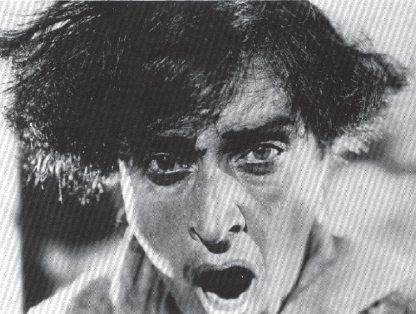

At home, Battler menaces his daughter, who hides in a closet. Battler takes an ax to the door. Here, Griffith intercut between three locations: the closet (where the fearful, trapped young woman is hiding), the living room (where the belligerent Battler is attacking his daughter), and the suitor's bedroom (where he has found the room destroyed). The suitor grabs a gun and leaves to try to rescue the young woman. Finally, Battler breaks through the door. The woman's fear is unbearable. Griffith cuts to two subjective close-ups: one of the young woman, and one of Battler (Figures 1.7 and 1.8). Battler pulls his daughter through the shattered door (Figure 1.9). The scene is terrifying in its intensity and in its inevitability. Battler beats his daughter to death. When the suitor arrives, he finds the young woman dead and confronts Battler (Figure 1.10), killing him. The story now rapidly reaches its denouement: the suicide of the suitor. He drapes the body of the young woman in silk and then peacefully accepts death.

Figure 1.1 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.2 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.3 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.4 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.5 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.6 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.7 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.8 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.9 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.10 |

Broken Blossoms, 1919. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Horror and beauty in Broken BIossoms are transmitted carefully to articulate every emotion. All of Griffith's editing skills came into play. He used close-ups, cutaways, and subjective camera placement to articulate specific emotions and to move us through a personal story with a depth of feeling rare in film. This was Griffith's gift, and through his work, editing and dramatic film construction became one.

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

There is little question that D. W. Griffith was the first great international filmmaker and that the drop in European production during World War I helped American production assume a far greater international position than it might have otherwise. It should not be surprising, then, that in 1918 Griffith and his editing innovations were the prime influence on filmmakers around the world. In the Soviet Union, Griffith's Intolerance was the subject of intense study for its technical achievements as well as for its ideas about society. In the ten years that followed its release, Sergei Eisenstein wrote about Griffith,7 V.I. Pudovkin studied Griffith and tried to perfect the theory and practice of communicating ideas through film narrative, and Dziga Vertov reacted against the type of cinema Griffith exemplified.

In France and Germany, filmmakers seemed to be as influenced by the other arts as they were by the work of other filmmakers. The influence of Max Reinhardt's theatrical experiments in staging and expressionist painting are evidenced in Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) (Figure 1.11). Sigmund Freud's ideas about psychoanalysis join together with Griffith's ideas about the power of camera movement in F. W. Murnau's The Last Laugh (1924). Griffith's ideas about camera placement, moving the camera closer to the action, are supplemented by ideas of distortion and subjectivity in E. A. Dupont's Variety (1925). In France, Carl Dreyer worked almost exclusively with Griffith's ideas about close-ups in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), and he produced one of the most intense films ever made.

Griffith accomplished a great deal. However, it was others in this silent period who refined and built upon his ideas about film editing.

VSEVOLOD I. PUDOVKIN: CONSTRUCTIVE EDITING AND HEIGHTENED REALISM

VSEVOLOD I. PUDOVKIN: CONSTRUCTIVE EDITING AND HEIGHTENED REALISM

Although all of the Soviet filmmakers were deeply influenced by Griffith, they were also concerned about the role of their films in the revolutionary struggle. Lenin himself had endorsed the importance of film in supporting the revolution. The young Soviet filmmakers were zealots for that revolution. Idealistic, energetic, and committed, they struggled for filmic solutions to political problems.

Perhaps none of the Soviet filmmakers was as critical of Griffith as V.I. Pudovkin.8 As Reisz suggests, “Where Griffith was content to tell his stories by means of the kind of editing construction we have already seen in the excerpt from The Birth of a Nation, the young Russian directors felt that they could take the film director's control over his material a stage further. They planned, by means of new editing methods, not only to tell stories but to interpret and draw intellectual conclusions from them.”9

Pudovkin attempted to develop a theory of editing that would allow filmmakers to proceed beyond the intuitive classical editing of Griffith to a more formalized process that could yield greater success in translating ideas into narratives. That theory was based on Griffith's perception that the fragmentation of a scene into shots could create a power far beyond the character of a scene filmed without this type of construction. Pudovkin took this idea one step further. As he states in his book,

The film director [as compared to the theater director], on the other hand, has as his material, the finished, recorded celluloid. This material from which his final work is composed consists not of living men or real landscapes, not of real, actual stage-sets, but only of their images, recorded on separate strips that can be shortened, altered, and assembled according to his will. The elements of reality are fixed on these pieces; by combining them in his selected sequence, shortening and lengthening them according to his desire, the director builds up his own “filmic” time and “filmic” space. He does not adapt reality, but uses it for the creation of a new reality, and the most characteristic and important aspect of this process is that, in it, laws of space and time invariable and inescapable in work with actuality become tractable and obedient. The film assembles from them a new reality proper only to itself.10

Figure 1.11 |

Dos Cabinet des Dr. Caligari, 1919. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Pudovkin thereby takes the position that the shot is the building block of film and that is the raw material whose ordering can generate any desired result. Just as the poet uses words to create a new perception of reality, the film director uses shots as his raw material.11

Pudovkin experimented considerably with this premise. His early work with Lev Kuleshov suggested that the same shot juxtaposed with different following shots could yield widely different results with an audience. In their famous experiment with the actor Ivan Mosjukhin, they used the same shot of the actor juxtaposed with three different follow-up shots: a plate of soup standing on a table, a shot of a coffin containing a dead woman, and a little girl playing with a toy. Audience responses to the three sequences suggested a hungry person, a sad husband, and a joyful adult, and yet the first shot was always the same.

Encouraged by this type of experiment, Pudovkin went further. In his film version of Mother (1926), he wanted to suggest the joy of a prisoner about to be set free. These are Pudovkin's comments about the construction of the scene:

I tried to affect the spectators, not by the psychological performances of an actor, but by the plastic synthesis through editing. The son sits in prison. Suddenly, passed in to him surreptitiously, he receives a note that the next day he is to be set free. The problem was the expression, filmically, of his joy. The photographing of a face lighting up with joy would have been flat and void of effect. I show, therefore, the nervous play of his hands and a big close-up of the lower half of his face, the corners of the smile. These shots I cut in with other and varied material—shots of a brook, swollen with the rapid flow of spring, of the play of sunlight broken on the water, birds splashing in the village pond, and finally a laughing child. By the junction of these components our expression of “prisoner's joy” takes shape.12

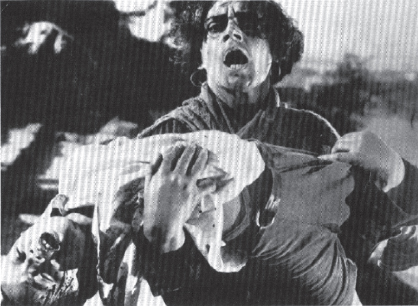

In this story of a mother who is politicized by the persecution of her son for his political beliefs, a personal approach is intermingled with a political story. In this sense, Pudovkin was similar in his narrative strategy to Griffith, but in purpose he was more political than Griffith. He also experimented freely with scene construction to convey his political ideas. When workers strike, their fate is clear (Figure 1.12); when fathers and sons take differing sides in a political battle, the family (in this case, the mother) will suffer (Figure 1.13); and family tragedy is the sacrifice necessary if political change is to occur (Figure 1.14).

Pudovkin first involves us in the personal story and the narrative, and then he communicates the political message. Although criticized for adopting bourgeois narrative techniques, Pudovkin carried those techniques further than Griffith, but not as far as his contemporary, Sergei Eisenstein.

SERGEI EISENSTEIN: THE THEORY OF MONTAGE

SERGEI EISENSTEIN: THE THEORY OF MONTAGE

Eisenstein was the second of the key Russian filmmakers. As a director, he was perhaps the greatest. He also wrote extensively about film ideas and eventually taught a generation of Russian directors. In the early 1920s, however, he was a young, committed filmmaker.

Figure 1.12 |

Mother, 1926. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 1.13 |

Mother, 1926. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 1.14 |

Mother, 1926. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

With a background in theatre and design, Eisenstein attempted to translate the lessons of Griffith and the lessons of Karl Marx into a singular audience experience. Beginning with Strike (1924), Eisenstein attempted to theorize about film editing as a clash of images and ideas. The principle of the dialectic was particularly suitable for subjects related to prerevolutionary and revolutionary issues and events. Strikes, the 1905 revolution, and the 1917 revolution were Eisenstein's earliest subjects.

Eisenstein achieved so much in the field of editing that it would be most useful to present his theory first and then look at how he put theory into practice. His theory of editing has five components: metric montage, rhythmic montage, tonal montage, overtonal montage, and intellectual montage. The clearest exposition of his theory has been presented by Andrew Tudor in his book Theories on Film.13

METRIC MONTAGE

Metric montage refers to the length of the shots relative to one another. Regardless of their content, shortening the shots abbreviates the time the audience has to absorb the information in each shot. This increases the tension resulting from the scene. The use of close-ups with shorter shots creates a more intense sequence (Figures 1.15 and 1.16).

Figure 1.15 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.16 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

RHYTHMIC MONTAGE

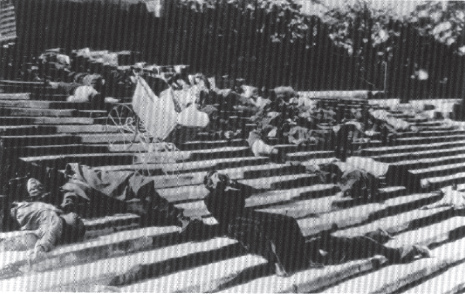

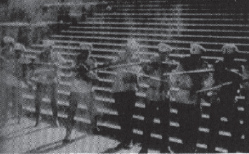

Rhythmic montage refers to continuity arising from the visual pattern within the shots. Continuity based on matching action and screen direction are examples of rhythmic montage. This type of montage has considerable potential for portraying conflict because opposing forces can be presented in terms of opposing screen directions as well as parts of the frame. For example, in the Odessa Steps sequence of Potemkin (1925), soldiers march down the steps from one quadrant of the frame, followed by people attempting to escape from the opposite side of the frame (Figures 1.17 to 1.21).

TONAL MONTAGE

Tonal montage refers to editing decisions made to establish the emotional character of a scene, which may change in the course of the scene. Tone or mood is used as a guideline for interpreting tonal montage, and although the theory begins to sound intellectual, it is no different from Ingmar Bergman's suggestion that editing is akin to music, the playing of the emotions of the different scenes.14 Emotions change, and so too can the tone of the scene. In the Odessa Steps sequence, the death of the young mother on the steps and the following baby carriage sequence highlight the depth of the tragedy of the massacre (Figures 1.22 to 1.27).

OVERTONAL MONTAGE

Overtonal montage is the interplay of metric, rhythmic, and tonal montages. That interplay mixes pace, ideas, and emotions to induce the desired effect from the audience. In the Odessa Steps sequence, the outcome of the massacre should be the outrage of the audience. Shots that emphasize the abuse of the army's overwhelming power and the exploitation of the citizens’ powerlessness punctuate the message (Figure 1.28).

INTELLECTUAL MONTAGE

Intellectual montage refers to the introduction of ideas into a highly charged and emotionalized sequence. An example of intellectual montage is the sequence in October (1928). George Kerensky, the Menshevik leader of the first Russian Revolution, climbs the steps just as quickly as he ascended to power after the Czar's fall. Intercut with his ascent are shots of a mechanical peacock preening itself. Eisenstein is making a point about Kerensky as politician. This is one of many examples in October (1928).

EISENSTEIN: THEORETICIAN AND AESTHETE

Eisenstein was a cerebral filmmaker, an intellectual with a great respect for ideas. Many of his later critics in the Soviet Union believed that he was too academic and his respect for ideas would supersede his respect for Soviet realism, that his politics were too aesthetic, and that his aesthetics were too individualistic.

Figure 1.17 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.18 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.19 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.20 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.21 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.22 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.23 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films. Stills provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.24 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films. Stills provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.25 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films. Stills provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.26 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films. Stills provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.27 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.28 |

Potemkin, 1925. Courtesy Janus Films. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

It is difficult for modern viewers to see Eisenstein as anything but a committed Marxist. His films are almost as naive as those of Griffith in their simple devotion to their own view of life. In the 1920s, whether he was aware of it or not, Eisenstein discovered the visceral power of editing and of visual composition, and he was a master of both. He was dangerous in the same sense that every artist is dangerous: He was his own person, a unique individual. Today, Eisenstein is greatly appreciated as a theoretician, but, like Griffith, he was also a great director. That is the extent of his crime.

DZIGA VERTOV: THE EXPERIMENT OF REALISM

DZIGA VERTOV: THE EXPERIMENT OF REALISM

If Eisenstein illustrated an editing theory devoted to reshaping reality to incite the population to support the revolution, Dziga Vertov was as vehement that only the documented truth could be honest enough to bring about true revolution.

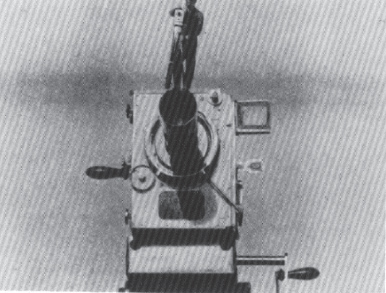

Vertov described his goals in the film The Man with a Movie Camera (1929) as follows: “The Man with a Movie Camera constitutes an experiment in the cinematic transmission of visual phenomena without the aid of intertitles (a film with no intertitles), script (a film with no script), theater (a film with neither actors nor sets). Kino-Eye's new experimental work aims to create a truly international film—language, absolute writing in film, and the complete separation of cinema from theater and literature.”15

Pudovkin remained interested in bourgeois cinema, and Eisenstein was too much the intellectual. Neither was sufficiently radical for Vertov, whose devotion to the truth is exemplified by his documentary, The Man with a Movie Camera. Because the film was the story of one day in the life of a film cameraman, Vertov repeatedly reminds the viewer of the artificiality and nonrealism of cinema. Consequently, nonrealism, manipulation, and all of the technical elements of film become part of this self-reflexive (looking on the director's own intentions and using film to explore those intentions and make them overt) film. Special effects and fantasy were part of those technical elements (Figures 1.29 to 1.32).

Although on paper Vertov seems doctrinaire and dry, on film he is quite the opposite. He edits in a playful spirit that suggests filmmaking is pleasurable as well as manipulative. This sense of fun is freer than the work of Pudovkin or Eisenstein. In attitude, Vertov's work is more experimental and free form than the work of his contemporaries. This sense of freedom and free association becomes particularly important in the work of Alexander Dovzhenko in the Ukraine and Luis Buñuel in France.

In terms of editing, Vertov is more closely aligned with the history of the experimental film than with the history of the documentary. In terms of his ideas, however, he is a forerunner of the cinema verité movement in documentary film, a movement that awaited the technical achievements of World War II to facilitate its development.

ALEXANDER DOVZHENKO: EDITING BY VISUAL ASSOCIATION

ALEXANDER DOVZHENKO: EDITING BY VISUAL ASSOCIATION

In his concept of intellectual montage, Eisenstein was free to associate any two images to communicate an idea about a person, a class, or a historical event. This freedom was similar to Vertov's freedom to be playful about the clash of reality and illusion, as illustrated by the duality of the filmmaking process in The Man with a Movie Camera. Alexander Dovzhenko, a Ukranian filmmaker, viewed as his goal neither straight narrative nor documentary. His film Earth (1930) is best characterized as a visual poem. Although it has as its background the class struggle between the well-to-do peasants (in the era of private farms) and the poorer farmers, Earth is really about the continuity of life and death. The story is unclear because of its visual indirectness, and it leads us away from the literal meaning of the images to a quite different interpretation.

The opening is revealing. It begins with a series of still images—tranquil, beautiful compositions of rural life: a young woman and a wild flower, a farmer and his ox, an old man in an apple orchard, a young woman cutting wheat, a young man filled with the joy of life. All of these images are presented independently, and there is no apparent continuity (Figures 1.33 to 1.37). Gradually, however, this visual association forms a pattern of pastoral strength and tranquillity. The narrative finally begins to suggest a family in which the grandfather is preparing to die, but dying surrounded by apples is not quite naturalistic. The cutting is not direct about the narrative intention, which is to illustrate the death of the grandfather while suggesting this event is the natural order of things, that is, life goes on. The apples being present in the images surrounding him, takes away from the sense of loss and introduces a poetic notion about death. The poetic sense is life goes on in spite of death. The old man returns to the earth willingly, knowing that he is part of the earth and it is part of him.

The editing is dictated by visual association rather than by classical continuity. Just as the words of a poem don't form logical sentences, the visual pattern in Earth doesn't conform to a direct narrative logic. Initially, the absence of continuity is confusing, but the pattern gradually emerges, and a different editing pattern replaces the classical approach. It is effective in its own way, but Dovzhenko's work is quite different from the innovations of Griffith. It does, however, offer a vastly different option to filmmakers, an option taken up by Luis Buñuel.

LUIS BUÑUEL: VISUAL DISCONTINUITY

LUIS BUÑUEL: VISUAL DISCONTINUITY

Surrealism, expressionism, and psychoanalysis were intellectual currents that affected all of the arts in the 1920s. In Germany, expressionism was the most influential, but among the artistic community in Paris, surrealism had an even greater influence. Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel, Spanish artists, were particularly attracted to the possibility of making surrealist film. Like Vertov in the Soviet Union, Buñuel and Dali reacted first against classical film narrative, the type of storytelling and editing represented by Griffith. Like Eisenstein, Buñuel particularly viewed the use of dialectic editing and counterpoint, setting one image off in reaction to another, as a strong operating principle.

Figure 1.29 |

The Man with a Movie Camera, 1929. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.30 |

The Man with a Movie Camera, 1929. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.31 |

The Man with a Movie Camera, 1929. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.32 |

The Man with a Movie Camera, 1929. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.33 |

Earth, 1930. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 1.34 |

Earth, 1930. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 1.35 |

Earth, 1930. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 1.36 |

Earth, 1930. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

Figure 1.37 |

Earth, 1930. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

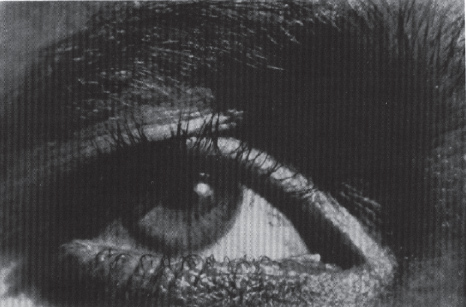

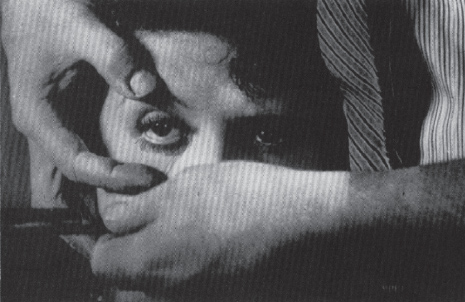

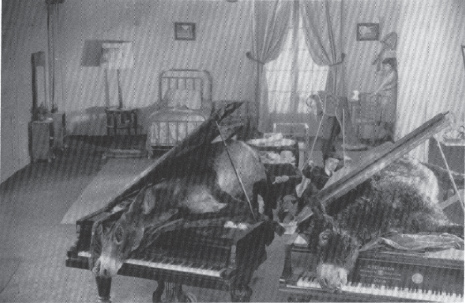

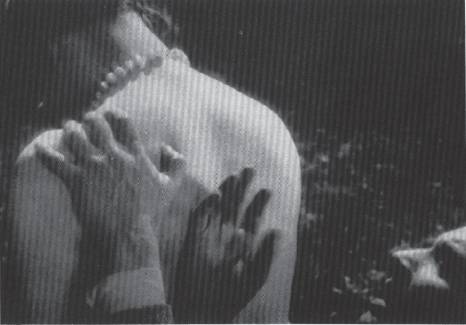

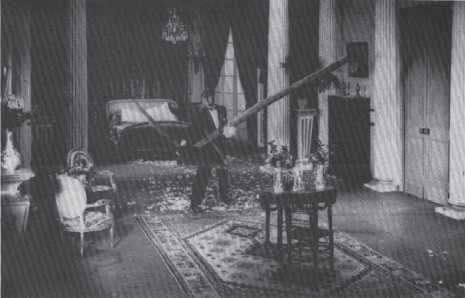

The filmic outcome was Un Chien d'Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) (1929). Buñuel particularly was interested in making a film that destroyed meaning, interspersed with the occasional shock. Suddenly, a woman's eye is being slashed, two donkeys are draped across two pianos, a hand exudes ants or caresses a shoulder (Figures 1.38 to 1.41).

The fact that the film has become as famous as it has is a result of what the film represents: a satirical set of shocks intended to speak to the audience's unconscious. Whether the images are dream-like and surreal or satiric remains open to debate. The importance of the film is that it represents the height of asynchronism; it is based on visual disassociation rather than on the classic rules of continuity. Consequently, the film broadens the filmmaker's options: to make sense, to move, to disturb, to rob of meaning, to undermine the security of knowing.

Figure 1.38 |

Un Chien d'Andalou, 1929. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.39 |

Un Chien d'Andalou, 1929. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.40 |

Un Chien d'Andalou, 1929. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 1.41 |

Un Chien d'Andalou, 1929. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

To frame Buñuel's contribution to film editing in another way, consider classic narrative storytelling as a linear progression. The plot begins with the character's achievement or final failure of achieving that goal. The plot follows the progress of the character in a linear fashion.

Buñuel, in undermining narrative expectations creates in essence a nonlinear plot. Character may be replaced by a new character or by a new goal for the old character. This nonlinearity can be frustrating for the viewer. But it also can open up the story to a new series of story options and consequent experiences for the audience.

In this sense, Buñuel creates at least philosophically a nonlinear experience for his audience. And he uses editing to do so.

Buñuel and Dali followed up Un Chien d'Andalou with a film that is a surreal narrative, L'Age d'Or (The Golden Age) (1930). In this film, a couple is overwhelmed by their passion for one another, but society, family, and Church stand against them and prevent them from being together. This is a film about great passion and great resistance to that passion. Again, the satiric, exaggerated imagery of surrealism interposes a nonrealistic commentary on the behavior of all. Passion, anger, and resistance can lead only to death. The film's images portray each state (Figures 1.42 to 1.46).

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

The silent period, 1885–1930, was an age of great creation and experimentation. It was the period when editing, unfettered by sound, came to maturity and provided a full range of options for the filmmaker. They included considerations of visual continuity, the deconstruction of scenes into shots, the development of parallel editing, the replacement of real time by a dramatic sense of time, poetic editing styles, the assertive editing theories of Eisenstein, and the asynchronous editing styles of Vertov and Buñuel. All of these became part of the editing repertoire.

One of the best examples of a filmmaker who combined the style of Griffith with the innovations of the Soviets was King Vidor. In his silent work, The Big Parade (1925) and The Crowd (1928), and later in his early sound work, Billy the Kid (1930) and Our Daily Bread (1934), he presented sequences that were narrative-driven, like Griffith's work, and idea- or concept-driven, like Eisenstein's. Both Griffith and Eisenstein were influential on the mainstream cinema, and their influence extended far beyond the silent period.

Figure 1.42 |

L'Age d'Or, 1936. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.43 |

L'Age d'Or, 1936. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.44 |

L'Age d'Or, 1936. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.45 |

L'Age d'Or, 1936. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Figure 1.46 |

L'Age d'Or, 1936. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |