2 |

The Early Sound Film |

||

A great many innovations in picture editing were compromised with the coming of sound. The early sound films have often been called filmed plays or radio plays with pictures as a result of the technological characteristics of early sound. In this period, however, there was an attempt to come to grips with the theoretical meaning of sound as well as an attempt to find creative solutions to overcome its technological limitations and to return to a more dynamic style of editing. It is to these early experiments in sound and picture editing that we now turn our attention.

TECHNOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS

TECHNOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS

Although experiments in sound technology had been conducted since 1895, it was primarily in radio and telephone transmission technology that advances were made. By 1927, when Warner Brothers produced the first sound (voice) feature film, The Jazz Singer with Al Jolson, at least two studios were committed to producing sound films. The Warner Brothers system, Vitaphone, was a sound-on-disk system. The Fox Corporation invested in a sound-onfilm system, Movietone. Photophone, an optical system produced by RCA, eventually became the industry standard. In 1927, though, Photophone had not yet been tested in an actual production, whereas Warner Brothers had used Vitaphone in The Jazz Singer and Fox had produced the popular Movietone news.

To use sound on film, several technological barriers had to be overcome. The problems revolved around the recording system, the microphone quality and characteristics, the synchronization of camera and sound disk playback, and the issue of sound amplification.

In the production process, the microphones used to record sound had to be sufficiently directional so that the desired voices and music were not drowned out by ambient noise.

A synchronization process was also needed. The camera recording the image and the disk recording the voice or music had to be in continuous synchronization so that, on playback, picture and sound would have a direct and constant relationship to one another. This system had to be carried through so that during projection the sound disk and the picture were synchronized. In sound-on-film systems, the sound reader had to be located on the projector so that it was read precisely at the instant when the corresponding image was passing under the light of the projector.

Finally, because film was projected in an auditorium or theater, the amplification system had to be such that the sound playback was clear and, to the extent possible, undistorted.

The recording of sound was so daunting a task that picture editing took second place. Dialogue scenes on disk could not be edited without losing synchronization. A similar problem existed with the Movietone sound-onfilm movies. A cut meant the loss of sound and image. Until rerecording and multiple camera use became common, editing was restricted to silent sequences. Consequently, the coming of sound meant a serious inhibition for editing and the loss of many of the creative gains made in the silent period.

This did not mean that film and film production did not undergo drastic changes in the early sound period. Suddenly, musicals and their stars became very important in film production. Stage performers and playwrights were suddenly needed. Journalists, novelists, critics, and columnists were in demand to write for the new dimension of speech on film. Those who had never spoken, the actors and their writers, fell from favor. The careers of the greatest silent stars—John Gilbert, Pola Negri, Emil Jannings, Norma Talmadge—all ended with the coming of sound. Many of the great silent comedians—Buster Keaton, Fatty Arbuckle, Harry Langdon—were replaced by verbal comedians and teams. W. C. Fields and the Marx Brothers were among the more successful. It was as if 30 years of visual progress were dismissed to celebrate speech, its power, and its influence.

Returning to the editing gains of the silent period, it is useful to understand why sound and picture editing today provides so many choices. The key is technological development. Today, sound is recorded with sophisticated unidirectional microphones that transmit sound to quarter-inch magnetic tape. Recording machines can mix sounds from different sources or record sound from a single source. The tape is transferred to magnetic film, which has the same dimensions as camera film and can be edge-numbered to coincide with the camera film's edge numbers. Original sound on tape is recorded in sync with the camera film so that camera film and magnetic film can be easily synchronized. Editing machines can run picture and sound in sync so that if synchronization is lost during editing it can be retrieved. Finally, numerous sound tracks are available for voice, sound effects, and music, and each is synchronized to the picture. Consequently, when those sound tracks are mixed, they remain in sync with the edited picture. When the picture negative is conformed to the working copy so the prints can be struck, an optical print of the sound is married to those prints from the negative. The married print, which is in sync, is used for projection.

The modern situation allows sound and picture to be disassembled so that editing choices in both sound and picture can proceed freely. Synchronization in picture and sound recording is fundamental to later synchronization. In the interim phases, the development of separate tracks can proceed because a synchronized relationship is maintained via the picture edit. Projection devices in which the sound head is located ahead of the picture allow the optical reading of sound to proceed in harmony with the image projection.

TECHNOLOGICAL IMPROVEMENTS

TECHNOLOGICAL IMPROVEMENTS

This freedom did not exist in 1930. It awaited a wide variety of technological improvements in addition to the decision to run sound and film at 24 frames per second (constant sound speed) rather than the silent speed of 16 frames per second (silent speed of film).

By 1929, camera blimps were developed to rescue the camera from being housed in the “ice box,” a sound-proofed room that isolated camera noise from the action being recorded. As camera blimps became lighter, the camera itself became more mobile, and the option of shooting sound sequences with a moving camera became realistic.

Set construction materials were altered to avoid materials that were prone to loud, crackling noises from contact. Sound stages for production were built to exclude exterior noise and to minimize interior noise.

Carbon arc lights, with their constant hum, were initially changed to incandescent lights. More sophisticated circuitry eventually allowed a return to quieter arc light systems.

By 1930, a sound and picture editing machine, the Moviola, was introduced. In 1932, “edge numbering” allowed sound and picture to be edited in synchronization. By 1933, advances in microphones and mixing allowed sound tracks to use music and dialogue simultaneously without loss of quality.

By 1936, the use of optical sound tracks was enhanced by new developments in optical light printers, which now provided distortionless sound. Quality was further enhanced by the development of unidirectional microphones in 1939.

Between 1945 and 1950, the use of magnetic recording over optical improved quality and permitted greater editing flexibility. Magnetic film began to replace optical film for sound editing.

Larger film formats, CinemaScope and TODD-AO, provided space on film for more than one optical track. Stored sound offered greater sound directionality and the sense of being surrounded by sound.

THEORETICAL ISSUES CONCERNING SOUND

THEORETICAL ISSUES CONCERNING SOUND

The theoretical debate about the use of sound was a deliberate effort to counter the observation that the sound film was nothing more than a filmed play complete with dialogue. It was an attempt to view the new technology of sound as a gain for the evolution of film as an art. Consequently, it was not surprising that the first expression of this impulse came from Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Grigori Alexandrov. Their statement was published in a Leningrad magazine in 1928.1

Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Alexandrov were concerned that the combination of sound and image would give the single shot a credibility it previously did not have. They worried that the addition of sound would counter the use of the shot as a building block that gains meaning when edited with other shots. They therefore argued that sound should not be used to enhance naturalism, but rather that it be used in a nonsynchronized or asynchronous fashion. This contrapuntal use of sound would allow montage to continue to be used creatively.

The next year, Pudovkin argued in his book Film Technique and Film Acting for an asynchronous use of sound. He believed that sound has far greater potential and that new layers of meaning can be achieved through the use of asynchronous sound. Just as he saw visual editing as a way of building up meaning, he viewed sound as an additional element to enrich meaning. In the early work of Alfred Hitchcock, Pudovkin's ideas are put into practice. We will return to Hitchcock later in this chapter.

Later, directors Basil Wright and Alberto Cavalcanti experimented with the use of sound in film. In the early 1930s, each argued that sound could be used, not only to counteract the realistic character of dialogue, but also to orchestrate a wide variety of sound sources—effects, narration, and music—to create a new reality. They viewed sound as an element that could liberate new meanings and interpretations of reality. Because both worked in documentary film, they were particularly sensitive to the “realism” affected by the visuals.

For the most part, these directors were attempting to find a way around the perceived tyranny of technology that resulted in the distortion of the sound film into filmed theatre. In their theoretical speculations, they pointed out the direction that enabled filmmakers to use sound creatively and to resume their attempts to find editing solutions for new narratives.

EARLY EXPERIMENT IN SOUND— ALFRED HITCHCOCK'S BLACKMAIL

EARLY EXPERIMENT IN SOUND— ALFRED HITCHCOCK'S BLACKMAIL

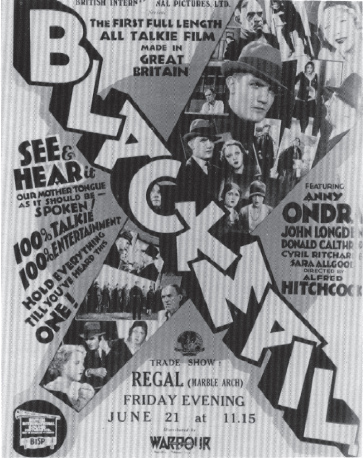

Alfred Hitchcock's Blackmail (1929) has many of the characteristics of the earliest sound films. It was shot in part as a silent film and in part as a sound film. The silent sequences have music and occasional sound effects. These sequences are dynamic—the opening sequence, which shows the apprehension and booking of a criminal by the police, is a good example. Camera movement is fluid, images are textured, and the editing is fast-paced. The sound sequences, on the other hand, are dominated by dialogue. The camera is static, as are the performers. The mix of silent and sound sequences of this sort typifies the earliest sound films. Hitchcock didn't let sound hamper him more than necessary, however. This story of a young woman (Anny Ondra) who kills an overzealous admirer (Cyril Ritchard) and is protected from capture by her Scotland Yard beau is simple on the surface, but Hitchcock treated it as a tale of desire and guilt. Consequently, these very subjective states are what he attempted to create through a mix of visuals and sound.

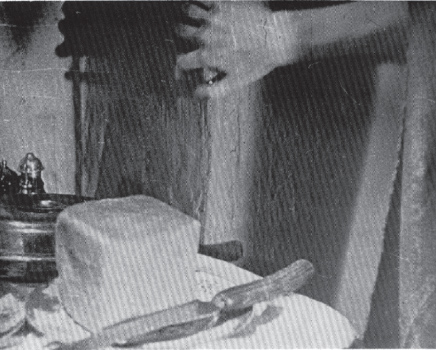

After the murder (Figures 2.1 to 2.3), Alice wanders the streets of London. A neon sign advertises Gordon's Gin cocktail mix, but instead of a cocktail shaker, Alice sees the stabbing motion of a knife. Later, this subjective suggestion is carried even further. She arrives home and pretends that she has spent the night there.

Figure 2.1 |

Figure 2.2 |

Blackmail, 1929. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Her mother wakes her for breakfast, mentioning the murder. She changes and goes to the confectioner's store, where a customer begins to gossip about the murder. The customer follows her into the breakfast room behind the store, continuing to talk about the murder instrument. The dialogue begins to focus on the word knife. The image we see is of Alice trying to contain herself. The dialogue over the visual of Alice is as follows: “.-.-.-Never use a knife-.-.-.-now mind you a knife is a difficult thing to handle-.-.-.-I mean any knife-.-.-.-knife-.-.-.-knife-.-.-.-knife-.-.-.” The word knife is now all that we (and Alice) hear, until she takes the knife to slice the bread. As she picks up the knife, the pitch and tone of the word changes from conversational to a scream of the word knife, and suddenly, she drops the knife.

This very subjective use of dialogue, allowing the audience to hear only what the character hears, intensifies the sense of subjectivity. As we identify more strongly with Alice, we begin to feel what she feels. The shock of the scream seems to wake us to the fact that there is an objective reality here also. Alice's parents are here for breakfast, and the customer is here for some gossip. Only Alice is deeply immersed in the memory of the murder the night before, and her guilt seems to envelop her.

Figure 2.3 |

Blackmail, 1929. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Hitchcock used sound as Pudovkin had envisioned, to build up an idea just as one would with a series of images. In Blackmail, sound is used as another bit of information to develop a narrative point: Alice's guilt over the murder. This early creative use of sound was achieved despite the technological limitations of dialogue scenes and despite silent sequences presented with music and simple sound effects. It was a hindrance because the static results of sound recording—no camera movement, no interference with the literal recording of that sound, means literal rather than creative use of sound. In Blackmail, Hitchcock transcends those limitations.

SOUND, TIME, AND PLACE: FRITZLANG'S M

SOUND, TIME, AND PLACE: FRITZLANG'S M

Fritz Lang's M (1931), although made only two years after Hitchcock's Blackmail, seems much more advanced in its use of sound, even though Lang faced many of the same technological limitations that Hitchcock did. Like Blackmail, Lang's film contains both dialogue sequences and silent sequences with music or sound effects. How did Lang proceed? In brief, he edited the sound as if he were editing the visuals.

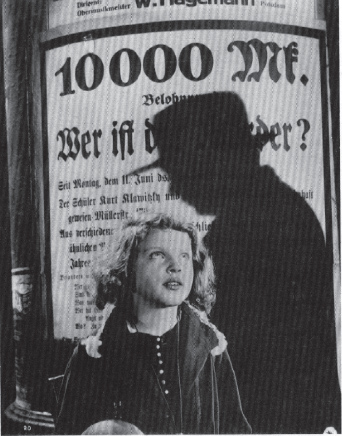

M is the story of a child murderer, of how he paralyzes a German city, and of how the underworld finally decides that if the police can't capture him, they will. The criminals and the police are presented as parallel organizations that are interested primarily in self-perpetuation. Only the capture of the child murderer will allow both organizations to proceed with business as usual. We are introduced to the murderer in shadow (Figure 2.4) when he speaks to a young girl, Elsie Beckmann. We hear the conversation he makes with her, but we see only his shadow, which is ironically shown on a reward poster for his capture.

Figure 2.4 |

M, 1931. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Lang then set up a parallel action sequence by intercutting shots of the murderer (Peter Lorre) with the young girl and shots of the young girl's mother. The culmination of this scene relies wholly on sound for its continuity. The mother calls out for her child. Each time she calls for Elsie, we see a different visual: out the window of the home, down the stairs, out into the yard where the laundry dries, to the empty dinner table where Elsie would sit, and finally far away to a child's ball rolling out of a treed area and to a balloon stuck in a telephone line. With each shot, the cries become more distant. For the last two shots, the mother's cries are no more than a faint echo.

In this sequence, the primary continuity comes from the soundtrack. The mother's cries unify all of the various shots, and the sense of distance implied by the tone of the call suggests that Elsie is now lost to her mother.

Later in the film, Lang elaborates on this use of sound to provide the unifying idea for a sequence. In one scene, the minister complains to the chief of police that they must find the killer of Elsie Beckmann. The conversation reveals the scope of the investigation. As they speak, we see visual details of the search for the killer. The visuals show a variety of activities, including the discovery of a candy wrapper at the scene of the crime and the subsequent investigation of candy shops. Geographically, the police investigation moves all around the town and takes place over an extended period of time. These time and place shifts are all coordinated through the conversation between the minister and the chief of police.

In terms of screen time, the conversation is five minutes long, but it communicates an investigation that takes place over many days and in many places. We sense the police department's commitment but also its frustration at the lack of results.

What follows is the famous scene of parallel action where Lang intercut two meetings. The police and the criminal underworld meet separately, and the leaders of both organizations discuss their frustrations about the child murderer and devise strategies for capturing him.

Rather than simply relying on visual parallel action, Lang cut on dialogue at one point, starting a sentence in the police camp and ending it in the criminal meeting. The crosscutting is all driven by dialogue. There are common visual elements: the meeting setting, the smoky room, the seating, the prominence of one leader in each group. Despite these visual cues, it is the dialogue that is used to set up the parallel action and to give the audience a sense of progress. Unlike Griffith's chase, there is no visual dynamic to carry us toward a resolution, nor is there a metric montage. The pace and character of the dialogue establish and carry us through this scene.

Lang used sound as if it were another visual element, editing it freely. Notable is how Lang used the design of sound to overcome space and time issues. Through his use of dialogue over the visuals, time collapses and the audience moves all about the city with greater ease than if he had straightcut the visuals (Figures 2.5 to 2.7).

Figure 2.5 |

M, 1931. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 2.6 |

Figure 2.7 |

M, 1931. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

THE DYNAMIC OF SOUND: ROUBEN MAMOULIAN'S APPLAUSE

THE DYNAMIC OF SOUND: ROUBEN MAMOULIAN'S APPLAUSE

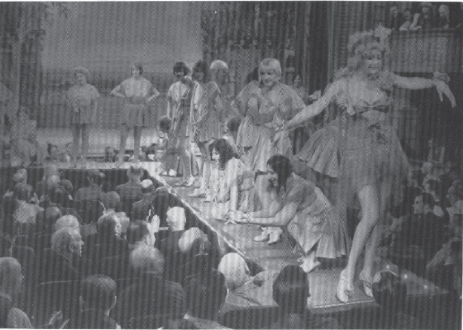

As Lucy Fischer suggests, “Mamoulian seems to ‘build a world’—one that his characters and audience seem to inhabit. And that world is ‘habitable’ because Mamoulian vests it with a strong sense of space. Unlike other directors of the period he recognizes the inherent spatial capacities of sound and, furthermore, understands the means by which they can lend an aspect of depth to the image.”2

Applause (1929) is a tale of backstage life, and it creates a world surrounded by sound (Figures 2.8 and 2.9). Even in intimate moments, the larger world expunges the characters. To capture this omnipresent sense of sound, Rouben Mamoulian added wheels to the sound-proof booth that housed the camera. As his characters moved, so did the camera and the sound. He also recorded two voices from two sources simultaneously. This challenge to technological limitations characterizes Mamoulian's attitude toward sound. Mamoulian realized that the proximity of the microphones to the characters would affect the audience's sense of closeness to the characters. Consequently, he used proximity and distance to good effect. Proximity meant that the characters (and the viewers) were surrounded and invaded by sound. Distance meant the opposite: total silence. Mamoulian used silence in Kitty's (Helen Morgan) suicide scene.

Figure 2.8 |

Applause, 1929. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 2.9 |

Applause, 1929. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

In this sense, Mamoulian used sound as long shot (silence) and close-up (wide open sound). It wasn't necessary to use sound and picture in synchrony. By using sound in counterpoint to the images, Mamoulian was able to heighten the dramatic character of the scenes.

This operating principle was elaborated and made more complex three years later in Mamoulian's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932). The Robert Louis Stevenson novel was adapted with a Freudian interpretation. Repressed sexuality leads Dr. Jekyll (Frederic March) to free himself to become the uninhibited Mr. Hyde. The object of his desire (and later his wrath) is Ivey (Miriam Hopkins).

To create an interior sense of Dr. Jekyll and to enhance the audience's identification with him, Mamoulian photographed the first 5 minutes with a totally subjective camera. We see what Dr. Jekyll sees. Consequently, we hear him but don't see him until he steps in front of the mirror. Poole, Jekyll's butler, announces that he will be late for a lecture at the medical school. We hear Jekyll as if we were directly beside him. The microphone's proximity gives us, in effect, “close-up” sound. Poole, on the other hand, is distant from the audience. At one point, the drop in sound is quite pronounced, a “long shot” sound.

This sense of spatial separation and character separation is continued when Jekyll enters the carriage that will take him to the medical school, but now the reverse begins to occur. The “close-up” sound is of the driver, and it is Jekyll who sounds distant. This continues when he is greeted by the medical school attendant.

Jekyll is now in the classroom, and all is silence. Then whispers by students and faculty can be heard. Only when Jekyll begins to lecture do the sound levels become more natural. When the film cuts to a closer visual of Jekyll, the sound also becomes a “close-up.” Consequently, what Jekyll is saying about the soul of man is verbally presented with as much emphasis as if it were a visual close-up.

Later, when Jekyll rescues Ivey from an abusive suitor, Mamoulian returns to this use of “visual” sound. He advises bed rest for her injuries. When she slips off her garter and her stockings, there is sudden silence, as though Jekyll were silenced by her sensuality. He tucks her into bed, and she embraces and kisses him just as his colleague, Lagnon, enters the room. Misunderstanding and embarrassment lead Jekyll and Lagnon to leave as Ivey, with one leg over the bed, whispers “Come back soon.

As Jekyll and Lagnon walk into the London night, Ivey and her provocative thigh linger as a superimposed image and the soundtrack repeats the whisper, “Come back soon.” The memory of Ivey and the desire for Ivey are recreated through the sound. Throughout the film, subjectivity, separation, desire, and dreams are articulated through the use of sound edits.

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

In their creative work, Mamoulian, Lang, and Hitchcock attempted to overcome the technological limitations of sound in this early period. Together with the theoretical statements of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and the documentary filmmakers, they prepared the industry to view sound not as an end in itself, but rather as another element that, along with the editing of the visuals, could help create a narrative experience that was unique to film.