6 |

Experiments in Editing: Alfred Hitchcock |

||

Few directors have contributed as much to the mythology of the power of editing as has Alfred Hitchcock. Eisenstein and Pudovkin used their films to work out and illustrate their ideas about editing, but Hitchcock used his films to synthesize the theoretical ideas of others and to deepen the repertoire by showcasing the possibilities of editing. His work embraces the full gamut of editing conceits, from pace to subjective states to ideas about dramatic and real time. This chapter highlights a number of set-pieces that he devoted to these conceits. Before beginning, however, we must acknowledge that Hitchcock may have experimented extensively with editing devices, but he was equally experimental in virtually every filmic device available to him.

Influenced by the visual experiment of F. W. Murnau and G. W. Pabst in the expressionist Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft (UFA) period, Hitchcock immediately incorporated the expressionist look into his early films. Because of the thematic similarities, elements of his visual style recur from Blackmail (1929) to Frenzy (1972). Particularly notable in the areas of set design and special effects are Spellbound (1945) and The Birds (1963). In Spellbound, Hitchcock turned to Salvador Dali to create the sets that represented the dreams of the main character, an amnesiac accused of murder. The sets represented a primary key to his repressed observations and feelings. Although not totally faithful to the tenets of psychoanalysis, Hitchcock's visualization of the unconscious remains a fascinating experiment. Equally notable for its visual experiments is the animation in The Birds. This tale of nature's revenge on humanity relies on the visualization of birds attacking people. The attack was created with animation. Again, the impulse to find the visual equivalent of an idea led Hitchcock to blend two areas of flimmaking—imaginative animation with live action—to achieve a synthesized filmic reality.

Hitchcock experimented with color in Under Capricorn (1949) and Marnie (1964). In Rear Window (1954), he made an entire film shot from the point of view of a man confined to a wheelchair in his apartment. Robert Montgomery experimented with subjective camera placement in Lady in the Lake (1946), but rarely had subjectivity been used as effectively as in Rear Window. Hitchcock was less successful in his experiment to avoid editing in Rope (1948), but the result is quite interesting. In this film, camera movement replaces editing; Hitchcock continually moved his camera to follow the action of the story.

Turning to Hitchcock's experiments in editing, what is notable is the breadth and audacity of the experimentation. Ranging from the subjective use of sound in Blackmail, which was discussed in Chapter 3, to the experiment in terror in the shower scene in Psycho (1960), Hitchcock established very particular challenges for himself, and the result has a sophistication in editing rarely achieved in the short history of film. To understand that level of sophistication, it is necessary to examine first the orthodox nature of Hitchcock's approach to the storytelling problem and then to look at how editing solutions provided him with exciting aesthetic challenges.

A SIMPLE INTRODUCTION: PARALLEL ACTION

A SIMPLE INTRODUCTION: PARALLEL ACTION

Strangers on a Train (1951) is the story of two strangers who meet on a train; one is a famous tennis player (Farley Granger), the other is a psychopath (Robert Walker). Bruno, the psychopath, suggests to Guy that if they murdered the person who most hampers the progress of the other's life, no one would know. There would be no motive.

So begins this story of murder, but before the offer is made, Hitchcock introduced us to the two strangers in a rather novel way. Using parallel editing, Hitchcock presented two sets of feet (we see no facial shots). One is going right to left, the other left to right, in a train station. The only distinguishing feature is that one of them wears the shoes of a dandy, the other rather ordinary looking shoes. Through parallel cutting between the movements right to left and left to right, we get the feeling that the two pairs of shoes are approaching one another. A shot of one of the men walking away from the camera toward the train dissolves to a moving shot of the track. The train is now moving. The film then returns to the intercutting of the two sets of feet, now moving toward each other on one car of the train. The two men seat themselves, still unidentified. The dandy accidentally kicks the other and finally the film cuts to the two men seated. The conversation proceeds.

In this sequence of 12 shots, Hitchcock used parallel action to introduce two strangers on a train who are moving toward one another. As is the case in parallel action, the implication is that they will come together, and they do.

A DRAMATIC PUNCTUATION: THE SOUND CUT

A DRAMATIC PUNCTUATION: THE SOUND CUT

Hitchcock found a novel way to link the concepts of trains and murders in The 39 Steps (1935). Richard Hannay (Robert Donat) has taken into his home a woman who tells him she is a spy and is being followed; she and the country are in danger. He is woken up by the woman, who now has a knife in her back and a map in her hand. To escape a similar fate, he pretends to be a milkman, sidesteps the murderers who are waiting for him, and takes a train to Scotland, where he will follow the map she has given him.

Hitchcock wanted to make two points: that Hannay is on his way to Scotland and that the murder of his guest is discovered. He also wanted to link the two points together as Hannay will now be a suspect in the murder investigation. The housekeeper opens the door to Hannay's apartment. In the background, we see the woman's body on the bed. The housekeeper screams, but what we hear is the whistle of the train. In the next shot, the rushing train emerges from a tunnel, and we know that the next scene will take place on the train.

The key elements communicated here are the shock of the discovery of the body and the transition to the location of the next action, the train. The sound carry-over from one shot to the next and its pitch punctuate how we should feel about the murder and the tension of what will happen on the train and beyond. Hitchcock managed in this brief sequence to use editing to raise the dramatic tension in both shots considerably, and their combination adds even more to the sense of expectation about what will follow.

DRAMATIC DISCOVERY: CUTTING ON MOTION

DRAMATIC DISCOVERY: CUTTING ON MOTION

This sense of punctuation via editing is even more compelling in a brief sequence in Spellbound. John Ballantine (Gregory Peck) has forgotten his past because of a trauma. He is accused of posing as a psychiatrist and of killing the man he is pretending to be. A real psychiatrist (Ingrid Bergman) loves him and works to cure him. She has discovered that he is afraid of black lines across a background of white. Working with his dream, she is convinced that he was with the real psychiatrist who died in a skiing accident. She takes her patient back to the ski slopes where he can relive the traumatic event, and he does. As they ski down the slopes, the camera follows behind them as they approach a precipice. The camera cuts closer to Ballantine and then to a close-up as the moment of revelation is acknowledged. The film cuts to a young boy sliding down an exterior stoop. At the base of the stoop sits his younger brother. When the boy collides with his brother, the young child is propelled onto the lattice of a surrounding fence and is killed. In a simple cut, from motion to motion, Hitchcock cut from present to past, and the continuity of visual motion and dramatic revelation provides a startling moment of discovery.

SUSPENSE:THE EXTREME LONG SHOT

SUSPENSE:THE EXTREME LONG SHOT

In Foreign Correspondent (1940), Johnnie Jones (Joel McCrea) has discovered that the Germans have kidnapped a European diplomat days before the beginning of World War II. The rest of the world believes that the diplomat was assassinated in Holland, but it was actually a double who was killed. Only Jones knows the truth. Back in London, he attempts to expose the story and unwittingly confides in a British politician (Herbert Marshall) who secretly works for the Nazis. Now Jones's own life is threatened. The politician assigns him a guardian, Roley, whose actual assignment is to kill him. Roley leads him to the top of a church (a favorite Hitchcock location), where he plans to push Jones to his death.

Roley holds a schoolboy up to see the sights below more clearly. The film cuts to a vertical shot that emphasizes how far it is to street level. The boy's hat blows off, and Hitchcock cut to the hat blowing toward the ground. The distance down is the most notable element of the shot. The schoolboys leave, and Jones and Roley are alone until a tourist couple interferes with Roley's plans. Shortly, however, they are alone again. Jones looks at the sights. The next shot shows Roley's outstretched hands rushing to the camera until we see his hands in close-up. Hitchcock then cut to an extreme long shot of a man falling to the ground. We don't know if it's Jones, but as the film cuts to pedestrians rushing about on the ground, a sense of anticipation builds about Jones's fate. Shortly, we discover that Jones has survived because of a sixth sense that made him turn around and sidestep Roley. For the moment that precedes this information, there is a shocking sense of what has happened and a concern that someone has died. Hitchcock built the suspense here by cutting from a close-up to an extreme long shot.

LEVELS OF MEANING: THE CUTAWAY

LEVELS OF MEANING: THE CUTAWAY

In The 39 Steps, Hannay is on the run from the law. He has sought refuge for the night at the home of a Scottish farmer. The old farmer has a young wife that Hannay mistakes for his daughter. When the three of them sit down for dinner, the farmer prays. Hannay, who has been reading the paper, notices an article about his escape and his portrayal as a dangerous murderer. As he puts down the paper at the table, the farmer begins the prayer. The farmer, suspecting a sexual attraction developing between his young wife and Hannay, opens his eyes as he repeats the prayer. Hannay tries to take his mind away from his fear. He eyes the wife to see if she suspects. Here, the film cuts to the headlined newspaper to illustrate Hannay's concern. The next shot of the wife registers Hannay's distraction, and as her eyes drift down to the paper, she realizes that he is the escaped killer. Hitchcock then cut to a three-shot showing the farmer eyeing Hannay and the wife now acknowledging visually the shared secret. These looks, however, confirm for the husband that the sexual bond between Hannay and the wife will soon strengthen. He will turn out this rival, not knowing that the man is wanted for a different crime.

In this sequence, the cutaway to the newspaper solidifies the sense of concern and communication between Hannay and the wife and serves to mislead the husband about their real fears and feelings.

INTENSITY: THE CLOSE-UP

INTENSITY: THE CLOSE-UP

In Notorious (1946), Alicia (Ingrid Bergman) marries Alex (Claude Rains) in order to spy on him. She works with Devlin (Cary Grant). Alex is suspected of being involved in nefarious activities. He is financed by former Nazis in the pursuit of uranium production. He is the leading suspect pursued by Devlin and the U.S. agency he represents. Alicia's assignment is to discover what that activity is. When she becomes suspicious of a locked wine cellar in the home, she alerts Devlin. He suggests that she organize a party where, if she secures the key, he will find out about the wine cellar.

In a 10-minute sequence, Hitchcock created much suspense about whether Devlin will find out about the contents of the cellar, whether Alicia will be unmasked as a spy, and whether it will be Alex's jealousy or a shortage of wine at the party that will unmask them. Alicia must get the key to Devlin, and she must show him to the cellar. Once there, he must find out what is being hidden there.

In this sequence, Hitchcock used subjective camera placement and movement to remind us about Alex's jealousy and his constant observation of Alicia and Devlin's activities. Hitchcock used the close-up to emphasize the heightened importance of the key itself and of the contents of a shattered bottle. He also used close-up cutaways of the diminishing bottles of party champagne to alert us to the imminence of Alex's need to go to the wine cellar. These cutaways raise the suspense level about a potential uncovering of Alicia and Devlin.

Hitchcock used the close-up to alert us to the importance to the plot of the key and of the bogus wine bottles and their contents. The close-up also increases the tension building around the issue of discovery.

THE MOMENT AS ETERNITY: THE EXTREME CLOSE-UP

THE MOMENT AS ETERNITY: THE EXTREME CLOSE-UP

There is perhaps no sequence in film as famous as the shower scene in Psycho.1 The next section details this sequence more precisely, but here the use of the extreme close-up will be the focus of concern.

The shower sequence, including prologue and epilogue, runs 2 minutes and includes 50 cuts. The sequence itself focuses on the killing of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), a guest at an off-the-road motel run by Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins). She is on the run, having stolen $40,000 from her employer. She has decided to return home, give the money back, and face the consequences, but she dies at the hands of Norman's “mother.”

The details of this scene, which takes place in the shower of a cheap motel bathroom, are as follows: the victim, her hands, her face, her feet, her torso, her blood, the shower, the shower head, the spray of water, the bathtub, the shower curtain, the murder weapon, the murderer.

Aside from the medium shots of Crane taking a shower and the murderer entering the inner bathroom, the majority of the other shots are close-ups of particular details of the killing. When Hitchcock wanted to register Crane's shock, her fear, and her resistance, he resorted to an extreme close shot of her mouth or of her hand. The shots are very brief, less than a second, and focus on a detail of the preceding, fuller shot of Crane. When Hitchcock wanted to increase the sense of shock, he cut to a subjective shot of the murder weapon coming down at the camera. This enhances the audience's shock and identification with the victim. The use of the extreme close-ups and the subjective shots makes the murder scene seem excrutiatingly long. This sequence seems to take an eternity to end.

DRAMATIC TIME AND PACE

DRAMATIC TIME AND PACE

In real time, the killing of Marion Crane would be over in seconds. By disassembling the details of the killing and trying to shock the audience with the killing, Hitchcock lengthened real time. As in the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin, the subject matter and its intensity allow the filmmaker to alter real time.

The shower scene begins with a relaxed pace for the prologue: the shots of Crane beginning her shower. This relaxed pacing returns after the murder itself, when Marion, now dying, slides down into the bathtub. With her last breath, she grabs the shower curtain and falls, pulling the curtain down over her. These two sequences—in effect, the prologue and epilogue to the murder—are paced in a regular manner. The sequence of the murder itself and its details rapidly accelerate in pace. The shot that precedes the murder runs for 16 seconds, and the shot that follows the murder runs for 18 seconds. In between, there are 27 shots of the details of the murder. These shots together run a total of 25 seconds, and they vary from half a second—12 frames—to up to one second—24 frames. Each shot is long enough to be identifiable. The longer shots feature the knife and its contact with Crane. The other shots of Crane's reaction, her shock, and the blood are shorter. This alternating of shorter shots of the victim and longer shots of the crime is exaggerated by the use of point-of-view shots: subjective shots that emphasize Crane's victimization. Pace and camera angles thus combine to increase the shock and the identification with the victim.

Although this sequence is a clear example of the manipulative power of the medium, Hitchcock has been praised for his editing skill and his ability to enhance identification. As Robin Wood suggests about the shower sequence, “The shower bath murder [is] probably the most horrific incident in any fiction film.”2 Wood also claims that “Psycho is Hitchcock's ultimate achievement to date in the technique of audience participation.”3

THE UNITY OF SOUND

THE UNITY OF SOUND

The remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) is commendable for its use of style to triumph over substance. If Psycho is the ultimate audience picture, filled with killing and nerve-wrenching unpredictability, The Man Who Knew Too Much is almost academic in its absence of emotional engagement despite the story of a family under threat. Having witnessed the killing of a spy, Dr. McKenna (James Stewart) and his wife Jo (Doris Day) are prevented from telling all they know when their son is kidnapped. The story begins in Marrakesh and ends in London, the scene of the crime.

Although we are not gripped by the story, the mechanics of the style are underpinned by the extensive use of sound, which is almost unmatched in any other Hitchcock film. This is best illustrated by looking at three sequences in the film.

In one sequence, Dr. McKenna is following up on information that the kidnappers have tried to suppress. McKenna was told by the dying spy to go to Ambrose Chapel to find the would-be killers of the prime minister. He mistakenly goes to Ambrose Chappell, a taxidermist, and doesn't realize that it is a false lead. He expects to find his son.

In this sequence, Hitchcock relies on a very low level of sound. Indeed, compared to the rest of the film, this sequence is almost silent. The audience is very aware of this foreboding silence. The result is the most tense sequence in the film. Hitchcock used moving camera shots of McKenna going warily toward the address. The streets are deserted except for one other man. The two eye each other suspiciously (we find out later that he is Ambrose Chappell, Jr.).

The isolation of McKenna, who is out of his own habitat in search of a son he fears he'll never see again, is underscored by the muted, unorchestrated sound in the sequence.

Another notable sequence is one of the last in the film. The assassination of the prime minister has been foiled, and the McKennas believe that their last chance is to go to the foreign embassy where they suspect their son is being held. At an embassy reception, Jo, a former star of the stage, is asked to sing.

She selects “Que Sera, Sera,” a melody that she sang to the boy very early in the film. She sings this lullaby before the diplomatic audience in the hope of finding her son.

The camera moves out of the room, and Hitchcock began a series of shots of the stairs leading to the second floor. As the shots vary, so does the tone and loudness of the song. The level of sound provides continuity and also indicates the distance from the singer. Finally, on the second floor, Hitchcock cut to a door, and then to a shot of the other side of the door. Now we see the boy trying to sleep. His mother's voice is barely audible.

The sequence begins a parallel action, first of the mother trying to sing louder and then the boy with his captor, Mrs. Drayton, beginning to hear and to recognize his mother.

Once that recognition is secure, the boy fluctuates between excitement and frustration. His captor encourages him to whistle, and the sound is heard by mother and father. Dr. McKenna leaves to find his son; Jo continues to sing. We know that the reunion is not far off. The unity of this sequence and the parallel action is achieved through the song.

The final sequence for this discussion is the assassination attempt, which takes place at an orchestra concert at Albert Hall. This rather droll, symphonic shooting is the most academic of the sequences; the unity comes from the music, which was composed and conducted by Bernard Herrmann. In just under 12½ minutes, Hitchcock visually scored the assassination attempt.

The characters of Hitchcock's symphony are Jo McKenna, her husband, the killer, his assistant, the victim, the prime minister and his party, conductor Herrmann, his soloist, his orchestra (with special emphasis on the cymbalist), and, of course, the concert-goers.

Hitchcock cut between all of these characters, trying to keep us moving through the symphony, which emphasizes the assassination with a clash of the cymbals. Through Jo, Hitchcock tried to keep the audience alert to the progress of the assassination attempt: the positioning of the killer, the raising of the gun. To keep the tension moving, Dr. McKenna arrives a few moments before the assassination, and it is his attempt to stop the killer that adds a little more suspense to the proceedings.

Hitchcock accelerated the pace of the editing up to the instant of the killing and the clash of the cymbals, which the killers hope will cover the noise of the gun being fired. Just before the clash, Jo screams, and the gunman fires prematurely. Her scream prompts the prime minister to move, and in doing so, he is wounded rather than killed by the shot. Although the death of the assassin follows after the struggle with Dr. MeKenna, the tension is all but over once the cymbals clash. As in the other two sequences, the unity comes from the sound: in this case, the symphony performed in Albert Hall.

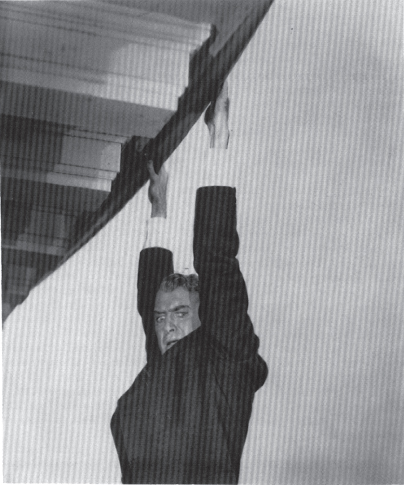

Figure 6.1 |

North by Northwest, 1959. ©1959 Turner Entertainment Company. All Rights Reserved. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

THE ORTHODOXY OF THE VISUAL: THE CHASE

THE ORTHODOXY OF THE VISUAL: THE CHASE

The famous cornfield sequence in North by Northwest (1959) is unembellished by sound (Figure 6.1). Without using music until the end of the sequence, Hitchcock devoted a 9½-minute sequence to man and machine: Roger Thorndike (Cary Grant) chased by a biplane. As usual in Hitchcock's films, the death of one or the other is the goal.

In this sequence of 130 shots, Hitchcock relied less on pace than one might expect in this type of sequence. In a sense, the sequence is more reminiscent of the fun of the Albert Hall sequence in The Man Who Knew Too Much than of the emotional power of the shower sequence in Psycho. It may be that Hitchcock enjoyed the visual challenge of these sequences and his film invites us to enjoy the abstracted mathematics of the struggle. The odds are against the hero, and yet he triumphs in the cornfield and in Albert Hall. It's the opposite of the shower sequence: triumph rather than torture.

In the cornfield sequence, Hitchcock used much humor. After Thorndike is dropped off on an empty Iowa road, he waits for a rendezvous with George Caplan. We know that Caplan will not come. Indeed, his persecutors think Thorndike is Caplan. Cars pass him by. A man is dropped off. Thorndike approaches him, asking whether he is Caplan. He denies it, saying he is waiting for a bus. Just as the bus arrives, he tells Thorndike that the biplane in the distance is dusting crops, but there are no crops there. This humor precedes the attack on Thorndike, which follows almost immediately.

Throughout the attack, Thorndike is both surprised by the attack and pleased by how he thwarts it. It is not until he approaches a fuel truck that the attack ends; but not before he is almost killed by the truck. As the biplane crashes into the truck, the music begins. With the danger over, the music grows louder, and Thorndike makes his escape by stealing a truck from someone who has stopped to watch the fire caused by the collision.

In this sequence of man versus machine, the orthodoxy of the visual design proceeds almost mathematically. The audience feels a certain detached joy. Without the organization of the sound, the battle seems abstract, emotionally unorchestrated. The struggle nevertheless is intriguing, like watching a game of chess; it is an intellectual battle rather than an emotional one.

The sequence remains strangely joyful, and although we don't relate to it on the emotional level of the shower scene, the cornfield sequence remains a notable accomplishment in pure editing.

DREAMSTATES: SUBJECTIVITY AND MOTION

DREAMSTATES: SUBJECTIVITY AND MOTION

Perhaps no film of Hitchcock's is as complex or as ambitious as Vertigo (1958), which is the story of a detective, Scottie (James Stewart), whose fear of heights leads to his retirement (Figure 6.2). The detective is hired by an old classmate to follow his wife, Madelaine (Kim Novak), whom he fears is suicidal, possessed by the ghost of an ancestor who had committed suicide. She does commit suicide by jumping from a church tower, but not before Scottie has fallen in love with her. Despondent, he wanders the streets of San Francisco until he finds a woman who resembles Madelaine and, in fact, is the same woman. She, too, has fallen in love, and she allows him to re-create her into the image of his lost love, Madelaine. They become the same, but in the end, he realizes that, together with Madelaine's husband, she duped him. They knew he couldn't follow her up the church stairs because of his fear of heights. He was the perfect witness to a “suicide.” Having uncovered the murder, he takes her back to the church tower, where she confesses and he overcomes his fear of heights. In the tower, however, she accidentally falls to her death, and Scottie is left alone to reflect on his obsession and his loss.

Figure 6.2 |

Vertigo, 1958. Copyright © by Universal City Studios, Inc. Courtesy of MCA Publishing Rights, a Division of MCA Inc. Still provided by Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives. |

This very dark story depends on the audience's identification with Scottie. We must accept his fear of heights and his obsession with Madelaine. His states of delusion, love, and discovery must all be communicated to us through the editing.

At the very beginning of the film, Hitchcock used extreme close-ups and extreme long shots to establish the source of Scottie's illness: his fear of heights. Hitchcock cut from his hand grabbing for security to long shots of Scottie's distance from the ground. As Scottie's situation becomes precarious late in the chase, the camera moves away from the ground to illustrate his loss of perspective. Extreme close-ups, extreme long shots, and subjective camera movement create a sense of panic and loss in his discovery of his illness. The scene is shocking not only for the death of a policeman but also for the main character's loss of control over his fate. This loss of control, rooted in the fear of heights, repeats itself in the way he falls in love with Madelaine. Assigned to follow her, he falls in love with her by watching her.

Scottie's obsession with Madelaine is created in the following way. Scottie follows Madelaine to various places—a museum, a house, a gravesite—and he observes her from his subjective viewpoint. This visual obsession implies a developing emotional obsession. What he is doing is far beyond a job. By devoting so much film to show Scottie observing Madelaine, Hitchcock cleverly forced the audience to relate to Scottie's growing obsession.

A midshot, full face shot of Scottie in the car is repeated as the base in these sequences. The follow-up shots of Madelaine's car moving down the streets of San Francisco are hypnotic because we see only a car, not a closeup or a midshot of Madelaine. All we have that is human is the midshot of Scottie. With these sequences, Hitchcock established Scottie's obsession as irrational—given his distance from Madelaine—as his fear of heights.

Another notable sequence takes place in the church tower where Madelaine commits suicide as Scottie watches, unable to force himself up the stairs. Scottie's fear of heights naturally plays a key role. The scene is shot from his point of view. He sees Madelaine quickly ascend the stairs. She is a shadow, moving rapidly. He looks up at her feet and body as they move farther away. Scottie's point of view is reinforced with crosscut shots of Scottie looking down. The distance is emphasized. When he is high enough, the fear sets in, and as in the first sequence, the sense of perspective changes as a traveling shot emphasizes the apparent shifting of the floor. These shots are intercut with his slowing to a stop on the stairs. The fear grows.

The ascending Madelaine is then intercut with the slowing Scottie and the ascending floor. Soon Scottie is paralyzed, and rapidly a scream and a point-of-view shot of a falling body follow. Madelaine is dead.

Point of view, pace, and sound combine in this sequence to create the sense of Scottie's panic and then resigned despair because he has failed. The editing has created that sense of panic and despair. All that now remains is for Vertigo to create the feeling of rebirth in Scottie's increasingly interior dream world.

This occurs after Scottie has insisted that Judy allow herself to be dressed and made up to look like Madelaine. Once her hair color is dyed and styled to resemble Madelaine's, the following occurs.

From Scottie's point of view, Judy emerges from the bedroom into a green light. Indeed, the room is bathed in different colors from green to red. She emerges from the light and comes into focus as Madelaine reborn. Scottie embraces her and seems to be at peace. He kisses her passionately, and the camera tracks around them. In the course of this 360-degree track, with the two characters in medium shot, the background of the room goes to black behind them. Later in the track, the stable where Scottie and Madelaine originally embraced comes into view. As the track continues, there is darkness and the hotel room returns as the background. In the course of this brief sequence, love and hope are reborn and Scottie seems regenerated.

Because this is a Hitchcock film, that happiness will not last. The scene in the church tower quickly proceeds, and this time Judy dies.

In the sequence featuring Judy's make-over as Madelaine, Hitchcock used subjectivity, camera motion, and the midshot in deep focus to provide context. The editing of the scene is not elaborate. The juxtapositions between shots and within shots are all that is necessary.

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Hitchcock was a master of the art of editing. He experimented and refined many of the classic techniques developed by Griffith and Eisenstein. Not only did he experiment with sound and image, but he enjoyed that experimentation. His enjoyment broadened the editor's repertoire while giving immeasurable pleasure to film audiences. His was a unique talent.