8 |

International Advances |

||

The year 1950 is a useful point to demarcate a number of changes in film history, among them the pervasive movement for change in film. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the growth in achievement and importance on an international level. Just as Hollywood experimented with the wide screen in this period, a group of British filmmakers challenged the orthodoxy of the documentary, a group of French writers who became filmmakers suggested that film authorship allowed personal styles to be expressed over industrial conventions, and young Italian filmmakers simplified narratives and film styles to politicize a popular art form. All sought alternatives to the classical style.

The classical style is best represented by such popular Hollywood filmmakers as William Wyler, who made The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). The film has a powerful narrative, and Wyler's grasp of style, including editing, was masterful but conventional. There were more exotic stylists, such as Orson Welles in The Lady from Shanghai (1948), but the mainstream was powerful and pervasive and preoccupied with more conventional stories.

By 1950, the Allies had won the war, and just as victory had brought affirmation of values and a way of life to the United States, the war and its end brought a deep desire for change in war-torn Europe. Nowhere was this impulse more quickly expressed than in European films. The neo-realist movement in Italy and the New Wave in France were movements dedicated to bringing change to film.

That is not to say that foreign films had not been influential before World War II. The contributions of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov from the Soviet Union, F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang of Germany, and Abel Gance and Jean Renoir of France were important to the evolution of the art of film. However, the primacy of Hollywood and of the various national cinemas was such that only fresh subject matter treated in a new and interesting style would challenge the status quo. These challenges, when they came, were of such a provocative and innovative character that they have profoundly broadened the editing of films. The challenges were broadly based: new ideas about what constitutes narrative continuity, new ideas about dramatic time, and a new definition of real time and its relationship to film time. All this came principally from those international advances that can be dated from 1950.

THE DYNAMICS OF RELATIVITY

THE DYNAMICS OF RELATIVITY

When Akira Kurosawa directed Rashomon (1951), he presented a narrative story without a single point of view. Indeed, the film presents four different points of view. Rashomon was a direct challenge to the conventions that the narrative clarity that the editor and director aim to achieve must come from telling the story from the point of view of the main character and that the selection, organization, and pacing of shots must dramatically articulate that point of view (Figure 8.1).

Rashomon is a simple period story about rape and murder. A bandit attacks a samurai traveling through the woods with his wife. He ties up the samurai, rapes his wife, and later kills the samurai. The story is told in flashback by a small group of travelers waiting for the rain to pass. The film presents four points of view: those of the bandit, the wife, the spirit of the dead samurai, and a woodcutter who witnessed the events. Each story is different from the others, pointing to a different interpretation of the behavior of each of the participants. In each story, a different person is responsible for the death of the samurai. Each interpretation of the events is presented in a different editing style.

Figure 8.1 |

Rashomon, 1951. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

After opening with a dynamic presentation of the woodcutter moving through the woods until he comes to the assault, the film moves into the story of the bandit Tajomaru (Toshiro Mifune). The bandit is boastful and without remorse. His version of the story makes him out to be a powerful, heroic figure. Consequently, when he fights the samurai, he is doing so out of respect to the wife who feels she has been shamed and that only a fight to the death between her husband and the bandit can take away the stain of being dishonored.

The presentation of the fight between the samurai and Tajomaru is dynamic. The camera moves, the perspective shifts from one combatant to the other to the wife, and the editing is lively. Cutting on movement within the frame, we move with the combat as it proceeds. The editing style supports Tajomaru's version of the story. The combat is a battle of giants, of heroes, fighting to the death. The editing emphasizes conflict and movement. The foreground–background relationships keep shifting, thereby suggesting a struggle of equals rather than a one-sided fight. This is quite different from all of the other versions presented.

The second story, told from the point of view of the wife, is much less dynamic; indeed, it is careful and deliberate. In this version, the bandit runs off, and the wife, using her dagger, frees the samurai. The husband is filled with scorn because his wife allowed herself to be raped. The question here is whether the wife will kill herself to save her honor. The psychological struggle is too much, and the wife faints. When she awakes, her husband is dead, and her dagger is in his chest.

The wife sees herself as a victim who wanted to save herself with as much honor as she could salvage, but tradition requires that she accept responsibility for her misfortune. Whether she killed her husband for pushing her to that responsibility or whether he is dead by his own hand is unclear. With its deliberateness and its emphasis on the wife's point of view, the editing supports the wife's characterization of herself as a victim. The death of her husband remains a mystery.

The third version is told from the point of view of the dead husband. His spirit is represented by a soothsayer who tells his story: The shame of the rape was so great that, seeing how his wife lusts after the bandit, the samurai decided to take his own life using his wife's dagger.

The editing of this version is dynamic in the interaction between the present—the soothsayer—and the past—her interpretation of the events. The crosscutting between the soothsayer and the samurai's actions is tense. Unlike the previous version, there is a tension here that helps articulate the samurai's painful decision to kill himself. The editing helps articulate his struggle in making that decision and executing it.

Finally, there is the version of the witness, the woodcutter. His version is the opposite of the heroic interpretation of the bandit. He suggests that the wife was bedazzled by the bandit and that a combat between Tajomaru and the samurai did take place but was essentially a contest of cowards. Each man seems inept and afraid of the other. As a result, the clash is not dynamic but rather amateurish. The bandit kills the samurai, but the outcome could as easily have been the opposite.

The editing of this version is very slow. Shots are held for a much longer time than in any of the earlier interpretations. The camera was close to the action in the bandit's interpretation, but here it is far from the action. The result is a slow, sluggish presentation of a struggle to the death. There are no heroes here.

By presenting a narrative from four perspectives, Kurosawa suggested not only the relativity of the truth, but also that a film's aesthetic choices—from camera placement to editing style—must support the film's thesis. Kurosawa's success in doing so opens up options in terms of the flexibility of editing styles even within a single film. Although Kurosawa did not pursue this multiple perspective approach in his later work, Rashomon did show audiences the importance of editing style in suggesting the point of view of the main character. An editing style that could suggest a great deal about the emotions, fears, and fantasies of the main character became the immediate challenge for other foreign filmmakers.

THE JUMP CUT AND DISCONTINUITY

THE JUMP CUT AND DISCONTINUITY

The New Wave began in 1959 with the consecutive releases of François Truffaut's The 400 Blows and Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless, but in fact its seeds had developed ten years earlier in the writing of Alexandre Astruc and André Bazin and the film programming of Henri Langlois at the Cinémathèque in Paris. The writing about film was cultural as well as theoretical, but the viewing of film was global, embracing film as part of popular culture as well as an artistic achievement. What developed in Paris in the post-war period was a film culture in which film critics and lovers of film moved toward becoming filmmakers themselves. Godard, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, Alain Resnais, and Jacques Rivette were all key figures, and it was Truffaut who wrote the important article “Les Politiques des Auteurs,” which heralded the director as the key creative person in the making of a film.

These critics and future filmmakers wrote about Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, Samuel Fuller, Anthony Mann, and Nicholas Ray—all Hollywood filmmakers. Although he admired Renoir enormously, Truffaut and his young colleagues were critical of the French film establishment.1 They criticized Claude Autant-Lara and Rene Clement for being too literary in their screen stories and not descriptive enough in their style. What they proposed in their own work was a personal style and personal stories—characteristics that became the hallmarks of the New Wave.

In his first film, The 400 Blows, Truffaut set out to respect Bazin's idea that moving the camera rather than fragmenting a scene was the essence of discovery and the source of art in film.2 The opening and the closing of the film are both made up of a series of moving shots, featuring the beginning of Paris, the Eiffel Tower,3 and later the lead character running away from a juvenile detention center. The synchronous sound recorded on location gives the film an intimacy and immediateness only available in cinema verité. It was the nature of the story, though, that gave Truffaut the opportunity to make a personal statement. The 400 Blows is the story of Antoine Doinel, a young boy in search of a childhood he never had. The rebellious child is unable to stay out of trouble at home or in school. The adult world is very unappealing to Antoine, and his clashes at home and at school lead him to reject authority and his parents. The story may sound like a tragedy that inevitably will lead to a bad end, but it is not. Antoine does end up in a juvenile detention center, but when he runs away, it is as rebellious as all of his other actions. Truffaut illustrated a life of spirit and suggested that challenging authority is not only moral, but it is also necessary for avoiding tragedy. The film is a tribute to the spirit and hope of being young, an entirely appropriate theme for the first film of the New Wave.

How did the stylistic equivalents of the personal story translate into editing choices? As already mentioned, the moving camera was used to avoid editing. In addition, the jump cut was used to challenge continuity editing and all that it implied.

The jump cut itself is nothing more than the joining of two noncontinuous shots. Whether the two shots recognize a change in direction, focus on an unexpected action, or simply don't show the action in one shot that prepares the viewer for the content of the next shot, the result of the jump cut is to focus on discontinuity. Not only does the jump cut remind viewers that they are watching a film, it is also jarring. This result can be used to suggest instability or lack of importance. In both cases, the jump cut requires the viewer to broaden the band of acceptance to enter the screen time being presented or the sense of dramatic time portrayed. The jump cut asks viewers to tolerate the admission that we are watching a film or to temporarily suspend belief in the film. This disruption can help the film experience or harm it. In the past, it was thought that the jump cut would destroy the experience. Since the New Wave, the jump cut has simply become another editing device accepted by the viewing audience. They have accepted the notion that discontinuity can be used to portray a less stable view of society or personality or that it can be accepted as a warning. It warns viewers that they are watching a film and to beware of being manipulated. The jump cut was brought into the mainstream by the films of the New Wave.

Two scenes in The 400 Blows stand out for their use of the jump cut, although jump cutting is used throughout the film. In the famous interview with the psychologist at the detention center, we see only Antoine Doinel. He answers a series of questions, but we neither hear the questions nor see the questioner.4 By presenting the interview in this way, Truffaut was suggesting Antoine's basic honesty and how far removed the adult world is from him. Because we see what Antoine sees, not viewing the psychologist is important in the creation of Antoine's internal world.

At the end of the film, Antoine escapes from the detention center. He reaches the seashore and has no more room to run. There is a jump cut as Antoine stands at the edge of the water. The film jumps from long shot to a slightly closer shot and then again to midshot. It freeze-frames the midshot and jump cuts to a freeze-frame close-up of Antoine. In this series of four jump cuts, Truffaut trapped the character, and as he moved in closer, he froze him and trapped him more. Where can Antoine go? By ending the film in this way, Truffaut trapped the character and trapped us with the character. The ending is both a challenge and an invitation in the most direct style. The jump cut draws attention to itself, but it also helps Truffaut capture our attention at this critical instant.

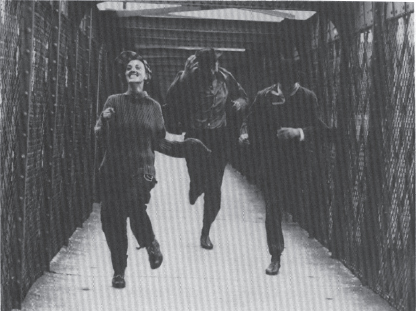

Truffaut used the jump cut even more dynamically in Jules et Jim (1961), a period story about two friends in love with the same woman. Whenever possible, Truffaut showed all three friends together in the same frame, but to communicate how struck the men are upon first meeting Catherine (Jeanne Moreau), Truffaut used a series of jump cuts that show Catherine in close-up and in profile and that show her features. This brief sequence illustrates the thunderbolt effect Catherine has on Jules and Jim (Figures 8.2 and 8.3).

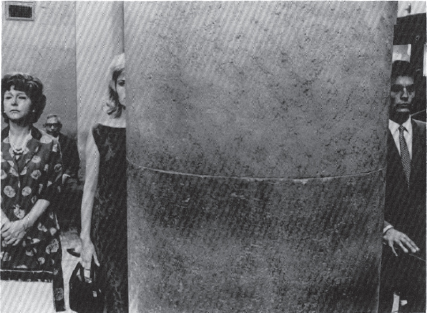

Figure 8.2 |

Jules et Jim, 1961. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

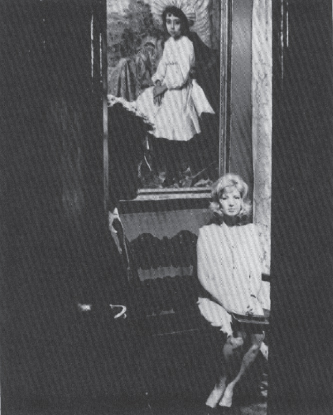

Figure 8.3 |

Jules et Jim, 1961. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by Moving Image and Sound Archives. |

Whether the jump cut is used to present a view of society or a view of a person, it is a powerful tool that immediately draws the viewer's attention. Although self-conscious in intent when improperly used, the jump cut was an important tool of the filmmakers of the New Wave. It was a symbol of the freedom of film in style and subject, of its potential, and of its capacity to be used in a highly personalized way. It inspired a whole generation of filmmakers, and may have been the most lasting contribution of the New Wave.5

OBJECTIVE ANARCHY: JEAN-LUC GODARD

OBJECTIVE ANARCHY: JEAN-LUC GODARD

Perhaps no figure among the New Wave filmmakers raised more controversy or was more innovative than Jean-Luc Godard.6 Although attracted to genre films, he introduced his own personal priorities to them. As time passed, these priorities were increasingly political. In terms of style, Godard was always uncomfortable with the manipulative character of narrative storytelling and the camera and editing devices that best carried out those storytelling goals. Over his career, Godard increasingly adopted counterstyles. If continuity editing supported what he considered to be bourgeois storytelling, then the jump cut could purposefully undermine that type of storytelling. If sound could be used to rouse emotion in accordance with the visual action in the film, Godard would show a person speaking about a seduction, but present the image in mid- to long shot with the woman's face totally in shadow. In shadow, we cannot relate as well to what is being said, and we can consider whether we want to be manipulated by sound and image. This was a constant self-reflexivity mixed with an increasingly Marxist view of society and its inhabitants. Rarely has so much effort been put into alienating the audience! In doing so, Godard posed a series of questions about filmmaking and about society.

Perhaps Godard's impulse toward objectification and anarchy can best be looked at in the light of Weekend (1967), his last film of this period that pretended to have a narrative. Weekend is the story of a Parisian couple who seem desperately unhappy. To save their marriage, they travel south to her mother to borrow money and take a vacation. This journey is like an odyssey. The road south is littered with a long multicar crash, and that is only the beginning of a journey from an undesirable civilization to an inevitable collapse leading, literally, to cannibalism. The marriage does not last the journey, and the husband ends up as dinner (Figures 8.4 and 8.5).

How does one develop a style that prepares us for this turn of events? In all cases, subversion of style is the key. A fight in the apartment parking lot descends into absurdity. The car crash, instead of involving us in its horror, is rendered neutral by a slow, objective camera track. In fact, once the camera has observed the whole lengthy crash, it begins to move back over the crash, front to back. When a town is subjected to political propaganda, the propagandists are interviewed head-on. Later, in a more rural setting, the couple comes across an intellectual (Jean-Pierre Leaud) who may be either mad or just bored with contemporary life. He reads aloud in the fields from Denis Diderot. Eventually, when revolution is the only alternative, the wife kills and eats the husband with her atavistic colleagues deep in the woods. At each stage, film style is used to subvert content. The result is a constant contradiction between objective film style and absurdist content or anarchistic film style and objective content. In both cases, the film robs the viewer of the catharsis of the conventional narrative and of the predictability of its style and meaning. There are no rules of editing that Godard does not subvert, and perhaps that is his greatest legacy. The total experience is everything; to achieve that total experience, all conventions are open to challenge.

Figure 8.4 |

Figure 8.5 |

Weekend, 1967. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

MELDING PAST AND PRESENT: ALAIN RESNAIS

MELDING PAST AND PRESENT: ALAIN RESNAIS

For Alain Resnais, film stories may exist on a continuum of developing action (the present), but that continuum must include everything that is part of the main character's consciousness. For Resnais, a character is a collection of memories and past experiences. To enter the story of a particular character is to draw on those collective memories because those memories are the context for the character's current behavior. Resnais's creative challenge was to find ways to recognize the past in the present. He found the solution in editing. An example illustrates his achievement.

Hiroshima Mon Amour (1960) tells the story of an actress making a film in Hiroshima. She takes a Japanese lover who reminds her of her first love, a German soldier who was killed in Nevers during the war. She was humiliated as a collaborator when she was 20 years old. Now, 14 years later, her encounter with her Japanese lover in the city destroyed to end the war takes her back to that time. The film does not resolve her emotional trauma; rather, it offers her the opportunity to relive it. Intermingled with the story are artifacts that remind her of the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima.

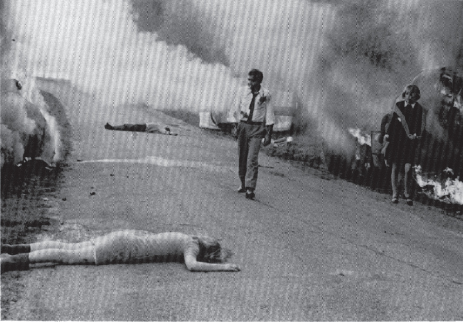

The problem of time and its relationship to the present is solved in an unusual way. The woman watches her Japanese lover as he sleeps. His arm is twisted. When she sees his hand, Resnais cut back and forth between a close-up of the hand and a midshot of the woman. After moving in closer, he cut from the midshot of the woman to a close-up of another hand (a hand from the past), then back to the midshot and then to a full shot of the dead German lover, his hand in exactly the same position as that of the Japanese lover. The full shot shows him bloodied and dead and the film then cuts back to the present (Figures 8.6 to 8.8).

The identical presentations of the two hands provides a visual cue for moving between the past and the present. The midshot of the woman watching binds the past and present.

Later, as the woman confesses to her contemporary lover, the film moves between Nevers and Hiroshima. Her past is interwoven into her current relationship, and by the end of the film, the Japanese lover is viewed as a person through whom she can relive the past and perhaps put it behind her. Throughout the film, it is the presence of the past in her present that provides the crucial context for the woman's affair and for her view of love and relationships. The past also comes to bear, in a less direct way, on the issues of war and politics and how a person can become immersed in them. The fluidity and formal quality of Resnais's editing fuses past and present for the character.

The issue of time and its relationship to behavior is a continuing trend in most of Resnais's work. From the blending of the past and present of Auschwitz in Night and Fog (1955) to the role of the past in the present identity of a woman in Muriel (1963) to the elevation of the past to the self-image of the main character in La Guerre Est Finie (1966), the exploration of editing solutions to narrative problems has been the key to Resnais's work.

Resnais carried on his exploration of memory and the present in Providence (1977), which embraces fantasy as well as memory. Later, he used the intellect, fantasy, and the present in Mon Oncle d'Amerique (1980). The greater the layers of reality, the more interesting the challenge for Resnais. Always, the solution lies in the editing.

Figure 8.6 |

Hiroshima Mon Amour, I960. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 8.7 |

Hiroshima Mon Amour, I960. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Figure 8.8 |

Hiroshima Mon Amour, 1960. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

INTERIOR LIFE AS EXTERNAL LANDSCAPE

INTERIOR LIFE AS EXTERNAL LANDSCAPE

The premise of many of Resnais's narratives—that the past lives on in the character—was very much the issue for both Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni. They each found different solutions to the problem of externalizing the interior lives of their characters.

When Fellini made 8½ in 1963, he was interested in finding editing solutions in the narrative. In doing so, he not only produced a film that marked the height of personal cinema, he also explored what, until that time, had been the domain of the experimental film: a thought rather than a plot, an impulse to introspection unprecedented in mainstream filmmaking (Figure 8.9).

8½ is the story of Guido (Marcello Mastroianni), a famous director. He has a crisis of confidence and is not sure what his next film will be. Nevertheless, he proceeds to cast it and build sets, and he pretends to everyone that he knows what he is doing. He is in the midst of a personal crisis as well as a creative one. His marriage is troubled, his mistress is demanding, and he dreams of his childhood. 8½ is the interior journey into the world of the past, of Guido's dreams, fears, and hopes. For 2½ hours, Fellini explores this interior landscape.

Figure 8.9 |

8½, 1963. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

To move from fantasy to reality and from past to present, Fellini must first establish the role of fantasy. He does so in the very first scene. Guido is alone in a car, stuck in a traffic jam. The traffic cannot be heard, just the sounds Guido makes as he breathes anxiously. The images begin to seem absurd. Suddenly we see other characters, older people in one car, a young woman being seduced in another. Are they dreams or are they reality? What follows blurs the distinction. The camera angle seems to indicate that she is looking straight at Guido (we later learn that she is his mistress). Suddenly, the car begins to fill with smoke. Guido struggles to get out, but people in other cars seem indifferent to his plight. His breathing is very labored now. Then he is out of the car and floating out of the traffic jam. We see a horseman, and Guido floats high in the air. An older man (we find out later that he is Guido's producer) suggests that he should come down. He pulls on Guido's leg, and he falls thousands of feet to the water below (Figure 8.10).

The film then cuts to neutral sound, and we discover that Guido has been having a nightmare. The film returns to the present, where Guido is being attended to in a spa. His creative team is also present. In this sequence, the fantasy is supported by the absurdist juxtaposition of images and by the absence of any natural sound other than Guido's breathing. The sound and the editing of the images provide cues that we are seeing a fantasy. This is a strategy Fellini again and again uses to indicate whether a sequence is fantasy or reality. For example, a short while later, Guido is outside at the spa, lining up for mineral water. The spa is populated by all types of people, principally older people, and they are presented in a highly regimented fashion. In a close-up, Guido looks at something, dropping his glasses to a lower point on his nose. The film cuts to a beautiful young woman (Claudia Cardinale), dressed in white, gliding toward him. The sound is suspended. Guido sees only the young woman. She smiles at him and is now very close. The film cuts back to the same shot of Guido in close-up. This time he raises his glasses back onto the bridge of his nose. At that instant, the sound returns, and the film cuts to a midshot of a spa employee offering him mineral water. Again, the sound cue alerts us to the shift into and out of the fantasy (Figure 8.11).

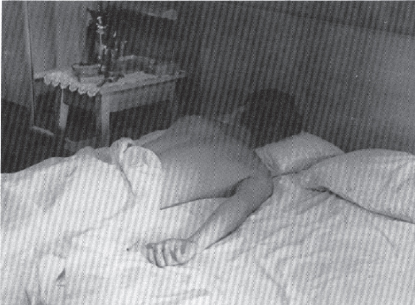

Figure 8.10 |

8½, 1963. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Throughout the film, Fellini also relies on the art direction (all white in the fantasy sequences) and on the absurdist character of the fantasies, particularly the harem-in-revolt sequence, to differentiate the fantasy sequences from the rest of the film. In the movement from present to past, a sound phrase—such as Asa-Nisi-Masa—is used to transport the contemporary Guido back to his childhood. Fellini also uses sound effects and music as cues. In 8½, Guido's interior life is as much the subject of the story as is his contemporary life. Although the film has little plot by narrative standards, the concept of moving around in the mind of a character poses enough of a challenge to Fellini that the audience's experience is as much a voyage of discovery as his seems to be. After that journey, film editing has never been defined in as audacious a fashion (Figure 8.12).

Figure 8.11 |

8½, 1963. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Michelangelo Antonioni chose not to move between the past and the present even though his characters are caught in as great an existential dilemma as Guido in 8½. Instead, Antonioni included visual detail that alludes to that dilemma. His characters live in the present, but they find despair in contemporary life. Whether theirs is an urban malaise born of upper-middle-class boredom or whether it's an unconscious response to the modern world, the women in his films are as lost as Guido. As Seymour Chatman suggests: “The central and distinguishing characteristic of Antonioni's mature films (so goes the argument of this book) is narration by a kind of visual minimalism, by an intense concentration on the sheer appearance of things—the surface of the world as he sees it—and a minimalization of exploratory dialogue.”7

We stay with Antonioni's characters through experiences of a variety of sorts. Something dramatic may happen in such an experience—an airplane ride, for example—but the presentation of the scene is not quite what conventional narrative implies it will be. In conventional narrative, an airplane ride illustrates that the character is going from point A to point B, or it illustrates a point in a relationship (the airplane ride being the attempt of one character to move along the relationship with another). There is always a narrative point, and once that point is made, the scene changes.

Figure 8.12 |

8½, 1963. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

This is the point in L'Eclisse (The Eclipse) (1962), for example. The airplane ride is an opportunity for the character to have an overview of her urban context: the city. It is an opportunity to experience brief joy, and it is an opportunity to admire the technology of the airplane and the airport. Finally, it is an opportunity to point out that even with all of the activity of a flight, the character's sense of aloneness is deep and abiding.

The shots that are included and the length of the sequence are far different than if there had been a narrative goal. Also notable are the number of long shots in which the character is far from the camera as if she is being studied by the camera (Figures 8.13 and 8.14).

L'Eclisse is the story of Vittoria (Monica Vitti), a young woman who is ending her engagement to Roberto as the film begins. She seems depressed. Her mother is very involved in the stockmarket and visits her daily to check on her health. Although Vittoria has friends in her apartment building, she seems unhappy. The only change in her mood occurs when she and her friends pretend they are primitive Africans. She can escape when she pretends.

Figure 8.13 |

L'Eclisse, 1962. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

One day, she visits her mother at the stock exchange. The market crashes and her mother is very bitter. Vittoria speaks to her mother's stockbroker, Piero (Alain Delon). He seems quite interested in her, and a relationship develops. The relationship seems to progress; the film ends inconclusively when she leaves his apartment, promising to meet in the evening. Her leavetaking is followed by a 7-minute epilogue of shots of life in the city. The epilogue has no visual reference to either Vittoria or Piero.

Whether one feels that the film is a condemnation of Piero's determinism and amorality or a meditation on Vittoria's existential state or her search for an alternative to a world dominated by masculine values, the experience of the film is unsettling and open. What is the meaning of the stock market? Vittoria says, “I still don't know if it's an office, a marketplace, a boxing ring, and maybe it isn't even necessary.” Piero's vitality seems much more positive than her skepticism and malaise. What is the meaning of the role of family? We see only her mother and her home. The mother is only interested in acquiring money. The family is represented by their home. They are personified by the sum of their acquisitiveness. What is meant by all of the shots of the city and its activity without the presence of either character?

One can only proceed to find meaning based on what Antonioni has given us. We have many scenes of Vittoria contextualized by her environment, her apartment, Roberto's apartment, Piero's two apartments, her mother's apartment, and the stock exchange. In these scenes, there is a foreground–background relationship between Vittoria, her habitat, and her relationship to others: her friends, Roberto, Piero, her mother. Antonioni alternated between objective and subjective camera placement to put the viewer in a position to identify with Vittoria and then to distance the viewer from Vittoria in order to consider that identification and to consider her state.

Figure 8.14 |

L'Eclisse, 1962. Courtesy Janus Films Company. Still provided by British Film Institute. |

Space is used to distance us, and when Vittoria exits into the city, these spaces expand. Filmed in extreme long shot with a deep-focus lens, the context alternates between Vittoria in midshot in the foreground and Vittoria in the deep background dwarfed by her surroundings, by the humanmade monuments, the buildings, and the natural monuments (the trees, the river, the forest).

Antonioni used this visual articulation, which for us means many slowly paced shots so that there is considerable screen time of Vittoria passing through her environment, rather than acting upon it as Piero does. What is fascinating about Antonioni is his ability in all of these shots to communicate Vittoria's sense of aloneness, and yet her sensuality (life force) is exhibited in the scene with her friends and in the later scenes with Piero. In these sequences, Antonioni used two-shots that included elements of the apartment: a window, the drapes. Because of the pacing of the shots, the film does not editorialize about what is most important or least important. All of the information, artifacts, and organization seem to affect Vittoria, and it is for us to choose what is more important than anything else.

If Antonioni's goal was to externalize the internal world of his characters, he succeeded remarkably and in different ways than did Fellini. Two sequences illustrate how the present is the basis for suggesting interior states in L'Eclisse.

When the relationship between Vittoria and Piero begins, Antonioni abandons all of the other characters. The balance of the film, until the very last sequence, focuses on the two lovers. In a series of scenes that take place in front of her apartment, at the site of his car's recovery from the river, in his parents’ apartment, in a park, and in his pied-à-terre, Vittoria gradually commits to a relationship with Piero. Although there is some uncertainty in the last scene as to whether the relationship will last, the film stays with the relationship in scene after scene. There is progress, but there isn't much dialogue to indicate a direct sense of progress in the relationship. The scenes are edited as if they were meditations on the relationship rather than as a plotted progression. The editing pattern is slow and reflective. The final sequence with the characters ends on a note of invasion from outside and of anxiety. As Vittoria leaves, Piero puts all of the phones back on the hook. As she descends the stairs, she hears as they begin to ring. The film cuts to Piero sitting at his desk wondering whether to answer them. In a very subtle way, this ending captures the anxiety in their relationship: Will it continue, or will the outside world invade and undermine it?

The epilogue of the film is also notable. In the last shot of the preceding sequence, Vittoria has left Piero's apartment. She is on the street. In the foreground is the back of her hand as she views the trees across the road. She turns, looks up, and then looks down, and she exits the frame, leaving only the trees.

The epilogue follows: 7 minutes without a particular character; 44 images of the city through the day. Antonioni alternates between inanimate shots of buildings and pans or tracks of a moving person or a stream. If there is a shape to the epilogue, it is a progression through the day. This sequence ends on a close-up of a brilliant street lamp. Throughout the sequence, sound becomes increasingly important. The epilogue relies on realistic sound effects and, in the final few shots, on music.

The overall feeling of the sequence is that the life of the city proceeds regardless of the state of mind of the characters. Vittoria may be in love or feeling vulnerable, but the existence of the tangible, physical world objectifies her feelings. To the extent that we experience the story through her, the sequence clearly suggests a world beyond her. It is a world Antonioni alluded to throughout the film. Early on, physical structures loom over Vittoria and Roberto. Later, when we see Vittoria and Piero for the first time, a column stands between them. The physical world has dwarfed these characters from the beginning. The existential problem of mortal humanity in a physically overpowering world is reaffirmed in this final sequence. Vittoria can never be more than she is, nor can her love change this relationship to the world in more than a temporal way. The power of this sequence is that it democratizes humanity and nature. Vittoria is in awe of nature, and she is powerless to affect it. She can only co-exist with it. This impulse to democratization—identification with the character and then a distancing from her—is the creative editing contribution of Michelangelo Antonioni.