In Chapter 7 I described how to get people’s attention, re-engage them, win support and start to build momentum to put things right. This is the necessary first step. But much more has to follow. Real control has to be regained. Workable solutions have to be found. They have to be implemented. In this chapter I will show how all this is done.

Digging till you find the cause

Explanations of what is failing and why will be rife. These might be good as far as they go, but will probably be incomplete. Work needs to start right away on the problems that everyone has agreed on, in order to show some quick progress. But, as a matter of the utmost priority, the root cause must be found. Look for three simple things: inability, delusion and deception. These will lead to the root cause.

Finding the root cause of failure

Here are some ideas for how to find your root cause:

- Listen, absorb, reflect.

- Reach out and talk to as many people as possible, to understand their perceptions, assumptions and expectations – many of which will be mutually conflicting.

- Put these together and reconcile them. This will give you a real sense of the prevailing culture.

- Ensure you have a yardstick of what the culture should be.

- Measure and judge the culture you have found against your yardstick.

It is only when you have done this that you will be able to find the solutions that are needed. The problems you unearth are likely to be fundamental, but you will also discover that problems which others have identified are not really problems: something else is going on.

- Keep digging until you find the root cause, because otherwise you will bury it and all your efforts will be as useful as putting sticking plaster on a bleeding wound.

- Use symptoms (notably the six warning signals described in detail in Chapters 4 and 5) to give you clues as to where to look for the root cause.

- As soon as you have identified the root cause, bring it out. You will be challenging conventional wisdom on the reasons for failure and you need to do it determinedly.

- Remember, as a newcomer, you have important temporary advantages that it is vital to use. If you don’t, you can quickly become part of the problem.

- Act quickly, even though bringing things out increases the perception (not the reality) of failure.

- Your analysis must lead not only to short-term action but also to the unfolding of a broad strategy, so that your staff and your bosses (i.e. whoever you are accountable to) can see that there is a clear and coherent way forward to reduce and ultimately solve the organisation’s problems. Setting out the broad strategy takes time but it must be done at the outset and continued into the future.

Once you have found the root cause, it becomes possible – even relatively straightforward – to find strategies to remove it. The root problem may be unknowingly determining behaviours or strategies, so that people do not realise they are being led astray. When I started to get to know Medway, for example, I realised that many of the behaviours that seemed to me odd or wrong derived from the perceived need to get a new hospital at virtually any cost. It was then relatively straightforward to change them to meet our real needs.

Having discovered what the wrong driver for the organisation has been and stopped it, it is important to identify what the real drivers should be. If one hasn’t got a prior view, this shouldn’t be too difficult. The key is to ask:

- What are the measures of the organisation’s success as seen by others (customers, investors, regulators)?

- What was it that made those others deem the organisation to be failing?

Tackling immediate problems

One other thing needs to be done immediately. Without doubt, there will be large, immediate problems rearing up in your face. You are in the middle of failure and no one has been tackling the problems successfully for some while. The key point is that the problems are explicitly identified and action is taken on them immediately. The problems might relate to finance, immediate operational difficulties, insufficient capacity/volume/output, lack of information and, related to that, lack of organisational grip. Operational problems are the most obvious, the most various and the most frequent. Here’s an example about car parking, about as generic and common an operational issue as you could wish for.

Dealing with gridlock at Medway

When I got the job of CEO at Medway, the two key things that you could not help seeing were that it had an almost completely new hospital building and that everyone was unhappy. How could this be? Enlightenment came when I noticed that outside the hospital there was semi-permanent gridlock. There were queues all day on all the key roads within the hospital as people tried to get through, to park or to get out. This meant that, not infrequently, ambulances trying to get to A&E were caught in a queue of cars. Local residents were irritated as they had a permanent jam just outside the hospital grounds and people were trying to park in the street to avoid the queues. To cap it all, there were insufficient spaces, so patients and staff were often unable to park. So absolutely everyone was irritated on a daily basis by this dysfunction.

The flow pattern of cars simply made no sense. Instead of having a flow of vehicles from the entrance past the main departments to A&E, we decided to map out another route, so that all patient and visitor cars stayed on the road around the periphery (which we made one-way), and we created a separate entry and exit for the car park. They got to and from the parking area without going near the main entrances, leaving the central road free and restricting it to vehicles which genuinely needed to go that way. In a trice, the queues evaporated. Local residents saw major improvements in their streets. The newspapers and the council, which had been pillorying the hospital for the mess, actually noticed and were pleased.

This left the problem of the lack of car parking. An ill-fated scheme to build a multi-storey car park to coincide with the opening of the hospital had collapsed a few months before and there were no other plans in place. I was told that the council was now ‘green’ and would not entertain proposals for extra car parking to meet our needs. ‘Don’t even bother asking for anything, they will humiliate you!’

I decided to meet the supposed arch-enemy of hospital car parking, the Director of Planning and Transportation. After about 10 minutes talking round the subject, it slowly dawned on us that we were each labouring under the misconception that our opinions differed. In fact our views on the extra car parking the hospital needed and how it might be provided were identical. The council had not been opposed to sensible plans, but was simply fed up of what it saw as a ‘fiddling while Rome burns’ attitude and wanted a sensible but not dogmatic recognition of environmental concerns.

We agreed what needed to be done. Within two months we put forward a plan and it was approved. With the council’s help the hospital’s car parking problems were solved.

The people who have stuck it out as things have gone badly wrong will almost certainly already have done a great deal under intense pressure but they will be struggling. What they need is a sense that they are making progress, including recognising what they have already achieved. Where recovery is not recognised or is seen as remission, the best way to accelerate it is to create a mindset based on open-mindedness and trust. It should involve early recognition and reinforcement of success, driving everyone into a virtuous circle of improvement.

With the right understanding and support, people’s actions become less desperate, less stressed and more balanced. If they have the confidence that they will be supported through their reasonable difficulties and mistakes, and that their improvements will be recognised, they sleep more easily and perform better. Here are some guidelines:

- Pinpoint the problem, open it up for scrutiny and obtain full information (typically numerical).

- Divide the problem into easy, doable bits and harder ones that will initially resist your efforts. The old adage about how to eat an elephant – in bite-size bits – applies. So, as soon as you can, do those ‘easy, doable bits’!

- Explain how you are doing it: use a clear methodology and set short-term targets that you know you will reach if you are systematic and careful. I did this at the Royal United Hospital, Bath. Each time we reached a target – and I set easy ones first – we celebrated it and told anyone who would listen about our success. The result was that the staff involved became much more self-confident and motivated, and knew they were and would be supported.

- Recognise the specific improvement rather than measuring against an absolute standard.

- Then, using that confidence and motivation, get onto the more difficult issues. The staff whom you need to deliver realise that the once seemingly impossible is now distinctly doable, and are actually quite keen to do it!

Tackling an obviously hard problem can also have tremendous symbolic significance. This is often exemplified in a very powerful but resistant or entrenched group. It was clear only weeks after I started a new job that such a group (in this case, of surgeons) had to be challenged head on – or disaster would follow, because their practices suited them but at the expense of the organisation’s smooth running. I met the group and told them that practices would have to change to avert the impending disaster. They pointed out that this would have an adverse effect upon their service, which was already teetering on the brink. Despite this, I insisted, believing that temporising would make an unacceptable position worse and could lead to a collapse in the service. This is (metaphorically) what I said: ‘I am opening a door here that we must all walk through. Now we have all walked through it I am closing it. Here is the key. I am locking the door and, look, I am throwing away the key.’ I made it clear that there was no going back – a fairly risky strategy for a new unknown, but one I felt I had to adopt. The results came swiftly: the risk of disaster disappeared, I kept being stopped in the corridor, an unknown of three weeks’ standing, by one senior figure after another, who congratulated me on finally doing something about what they saw as a festering problem – and what’s more, the service itself improved.

Here’s another example with central importance for the business concerned.

St Albans elective care centre

West Hertfordshire Hospitals NHS Trust opened a new elective care centre in St Albans in September 2007. It was part of a sound plan to rationalise and separate emergency and planned services. It opened a month before the Trust was precipitated into deep failure by being, for the second year running, joint worst in the country, in the annual hospital star ratings, with the subsequent resignation of its Chief Executive. On my arrival in November as the new Chief Executive, it was explained to me that the elective care centre was part of the solution not the problem, but it had ‘teething problems’. Together with my equally new Chief Operating Officer we had a look at what was going on. Two weeks in, we met and shared our conclusions: it didn’t have ‘teething problems’; it was an implementation disaster.

Why was this? It was overspending at a catastrophic rate and at the same time was completely unable to deal with the numbers of patients it had planned and needed to treat, thereby putting a huge amount of pressure on patient waits. When we looked into it, we saw what had happened. An implementation process had been set in train but it had not been monitored or followed through rigorously, and managers had not been held to account for identifying and correcting problems, so they built up and multiplied.

The first problem was that it had been assumed that staff would transfer from their existing hospital to St Albans, where the work was moving. Many chose not to do this. The Trust had a rigid recruitment freeze. Those planning the elective care centre felt they couldn’t recruit to replace the staff who didn’t transfer. This created staffing gaps. One response was to try to run operating theatres with fewer staff, but this proved impossible, so operating theatres were in many cases partially staffed but unable to run, with the result that patients weren’t treated but major staffing costs were still incurred. As this began to be realised managers did everything they could to run the operating theatres, buying in temporary agency staff to do so. However, the agency staff were much more expensive than permanent staff, so running these sessions was extremely expensive. Because a number of sessions were being cancelled due to staff shortages, the hospital Trust was contractually required to ensure patients who had been cancelled (and there were many) were treated within a month of their cancellation date. Obviously lacking the capacity to do this themselves, they had to send patients to private hospitals at a premium rate.

So each of the tactics cost a great deal of money, creating an absolutely enormous overspend. But the root cause was clear: there was no proper culture of performance management with clear accountability for following through and achieving organisational goals. We changed this and in changing it ensured there was realism about which theatre sessions we could staff. Those we couldn’t realistically staff, we closed down and saved the money on. We began and built up a vigorous recruitment effort and gradually reduced our use of temporary staff. Quickly we reduced most of the overspend and within a few months we eliminated it. The capacity of the theatres was increased as we increased staffing, leading to fewer cancellations and virtually eliminating the costly need to outsource work. The original plan had been sound but there was a fundamental failure of implementation and follow-through.

Rebuilding the mechanisms for managing

The next things that will need to be looked at are the structure, the team and the processes of the organisation. The mechanisms for managing will have fallen into partial or total disuse. Mechanisms having any usefulness should be resurrected, but the existing framework has failed and will need amendment and probably radical alteration. There will be little time to assess and act but the shortage of time can bring advantages:

- Plump for simple, inclusive, action-oriented mechanisms which everyone will be able to see are working.

- Be transparent: people should be able to see how their work relates to other work and who is responsible for what.

- Two-way communication must permeate the arrangements.

- Avoid as far as you can organising around the classic function-based silos of responsibility: operations, finance, HR, etc. By all means use these, but make them supportive.

- Articulate your structure around what people do, and the processes that define their work.

- Do not atomise or balkanise. Make connections critical to your structure.

- Above all, test that what is being created is an approach that is competent enough to tackle massive problems.

- Make sure the structure is able to get the many capable and key people on board who will be looking for a signal that they are wanted.

- Make accountability and responsibility absolutely clear – with clear consequences if either fails. People should not be able to say they have done their bit, but nothing seems to happen, they don’t know how to make it happen, or it isn’t for them to do so.

- Agree objectives, monitor performance and manage performance.

- Then devolve, devolve, devolve, but monitor explicitly and be seen to do so, on occasion by attending and actively participating in devolved meetings.

- Show that this level of oversight is also about support and enablement, so that people know that they are able to act.

Instead of simply ticking over, you can now really crank up the engine to drive forward. You should by now have put together a confident, determined, outgoing team who are committed to solving problems and who will be buttressed by your belief in them and their belief in themselves.

The overwhelming majority of your staff will be capable but in need of reassurance, support and possibly redirection. It is therefore crucial to signal your own positive judgements clearly and quickly. Don’t leave the Sword of Damocles hanging over people. Tell them they have your confidence, and why. It will send a wave of relief and motivation through the organisation. People will think: ‘Not only is there a way forward – which looks as though it will work – but I am part of it!’

A very small number of people, unfortunately, are usually part of the problem. They have mismanaged or misdefined the problem and don’t have the skills to work differently. If they can’t be placed somewhere else useful, it is vital to agree their exit quickly. They should be able to leave with dignity both for their sakes and for the message it gives to those who remain. Avoid any ‘night of the long knives’. Make the message considered and the transition considerate.

Unlocking the organisation

The next step is to build and deliver across the organisation. Much of this is about reshaping and restructuring, changing the organisation’s culture and raising morale. As described earlier in this book, a failing organisation typically suffers from fragmentation, passivity and fatalism; everyday processes have ceased to work or are only functioning on autopilot. The key to opening such a ‘locked’ organisation is getting the people within it to believe that a driving force exists to which they can respond, and in so doing can take part in renewing it. Demoralised staff, once they are convinced that they have a part to play in the future, become the solution rather than the problem.

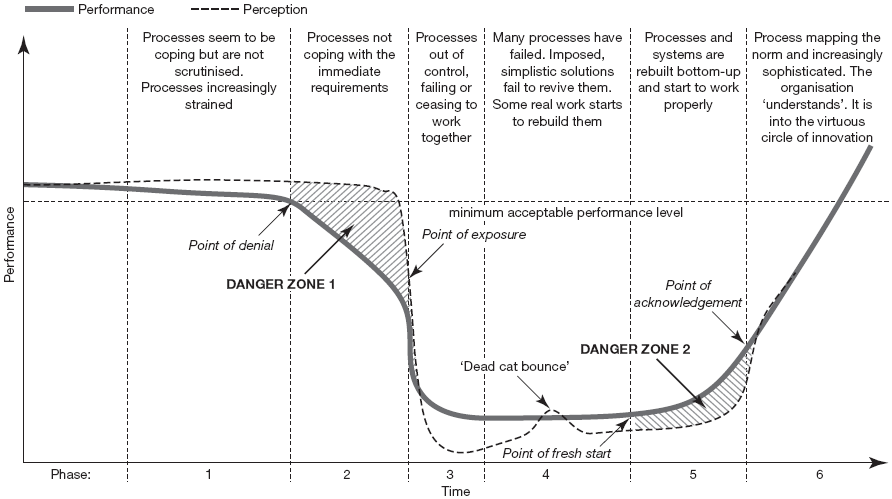

Systems and processes need to function smoothly and in line with an organisation’s needs. When the organisation fails they cease to do this, they fall apart. Look (on the next page) at the failure trajectory with processes in mind.

So how do you build or rekindle processes? Personal commitment from leadership is essential. This involves understanding what is required and having the determination to carry it through. Where those who identify barriers don’t have the power to remove them, assistance must be given, even extra resources. If this approach is adopted, it becomes self-sustaining and spreads across the organisation with decreasing resistance and increasing enthusiasm as positive results are seen.

The key initial steps I have described above are the prerequisites to getting into recovery. To embed and consolidate recovery requires the organisation to start firing on all cylinders. This means starting to work organically, cohesively and purposefully. Bear in mind:

- The recovery phase from failure typically raises staff morale and makes staff believe in themselves. This in turn can unleash huge enthusiasm and determination to do things better – a huge potential to innovate.

- If carefully utilised, this can catapult the recovering organisation into a leading organisation.

- Because it is disruptive, deep and radical innovation is less likely in smoothly functioning, untroubled organisations. But the conditions can be just right as you come out of the disruption of failure into the uplands of recovery.

Process redesign at Medway

At Medway Hospital when we started to implement a redesign of basic processes, it became evident that this was creating big improvements around the organisation and, very importantly, it was based on the insights of existing staff. As a result, individuals and teams offered to redesign other processes that they thought were defective. They felt confident that they would be supported by management, and they were. There was a blossoming of constructive process redesign, with the result that everything started to be done better throughout the organisation. An organisation that I had been told on my arrival was ‘universally mediocre’ was in less than three years lauded as ‘bristling with innovation’ by none other than the Secretary of State for Health.

It is vital that you don’t stop once you have achieved ‘average’. Go for exceptional and you will achieve it. The satisfaction, when it is publicly acknowledged that the organisation is flying, is immense and an enormous morale booster. A great and indisputable example of this comes from a now universally known and respected firm, Toyota. Toyota rose from being an impoverished, patronised assembler of cars in the wake of Japan’s total defeat in the Second World War to become the world’s most successful manufacturing company. It started getting it right in the 1950s and 1960s. It has continued to do so ever since (notwithstanding a few well-publicised problems with safety recalls). That’s what we all need to do.

To sum up …

Finding the root cause of the failure, which is often partly obvious but usually partly concealed, is critical to moving forward. Once it is found, there is firm ground to move forward on. And the first thing to do is to get stuck in to immediate, graspable problems, even if they appear minor or incidental; show progress on them, give the business some life. From there, a more permanent, structured approach can be used, rebuilding structures and processes so they are explicitly and freshly fit for purpose. With those in place, systematic delivery becomes feasible. Managers need to be able to do things. This sequence is designed to enable them to.

In the next part of the book, I will discuss the attributes and skills that ‘doing’ managers need.