Before I can credibly describe managerial approaches which work, will succeed and should produce the intended results, it is essential that I lay the positive foundation stones that will enable these things to happen. They are the opposites to many of the things I have described so far and they make sense in their own right. I will set them out in this chapter and build on them in the rest of the book.

Five key ideas

There are five key ideas which underpin my notion of what management is about, what we should recognise and what we should strive for as managers.

IDEA 1: DON’T BE TOO CONCERNED WITH THE OUTSTANDING

- Survival is about being sufficiently good.

- This does not mean a lack of ambition or a messy compromise.

- It is realistic; it is hard.

- It means knowing how you are measured and how that changes.

- It is achievable.

- It is permanent.

Imperfection characterises our world. Our understanding and our achievement are always imperfect. That means we will always need to do better. But the obverse of this is that if you are imperfect you can do better; there is something to aim for. If we keep seeking what are in effect extreme behaviours, at an extreme end of the spectrum, we will fail to learn how to behave in more normal, typical circumstances and we won’t have the sense of what we should give to our organisation and what our organisation should give to us.

Healthy people are not super athletes. Super athletes punish their bodies and become atypical specimens, brilliantly adapted for an extraordinarily special task and, by definition, not a model for others. They are about competition until only one is left.

It’s not just about our bodies either. The psychotherapist D.W. Winnicott gave us the concept of the ‘good-enough mother’ – the ‘ordinary devoted mother … an example of the way in which the foundations of health are laid down by the ordinary mother in her ordinary loving care of her own baby’. Don’t dismiss the imperfect and the ordinary. Understand them, appreciate them.

IDEA 2: DON’T SEE SUCCESS AS AN END POINT

- Good business is about continuing and continuous delivery.

- Real success is about: resilience, sustaining delivery, meeting new challenges, and staying in the game and on the ball.

This idea is so fundamental to what I have to say that I have been trailing it right from the beginning (see page xxiv). To repeat, avoid the trap of seeing failure as a state, and success as something that is impressive and laudable but passes quickly. Realise that it depends on you whether failure and success are states or points you pass through. You must take action to make failure a point you come out of. You must also take action to keep in a long-term state of success. The opposite state to failure is not short-term success but rather sustained achievement, success-FUL-ness.

With Idea 2 I am also seeking to put right another commonplace error in the received view of management. Repetition, constancy, survival and continuation may all be boring, but they are essential. We need to learn, relearn and remaster them. Exceptional success is fleeting and often unreal, and does not tell us what to do between the fleeting moments. So my message is:

- Keep going.

- Realise that there will always be new problems, new challenges and new errors.

- Be ready for them; look for them.

- Never see an end point or a particular target as a be-all and end-all.

- Targets are markers on the route you must continue on.

- Miss them and you have probably taken a wrong turning.

- Hit one and you still have to move forward.

IDEA 3: PERFECTION IN MANAGEMENT IS AN ILLUSION

- Real managers – good managers – are imperfect managers.

- They get things wrong, they realise that, and they learn from their mistakes.

- Good managers support managers who make mistakes.

- They take responsibility alongside them.

- They forgive them, so enabling learning and improvement.

Perfection tends to mean that an ideal and absolutely right end point can be reached. Imperfection, on the other hand, is about the messy everyday business of not fully understanding a problem, not necessarily getting it exactly right first time, but trying again until one does get it right, never giving up. It’s about being balanced and unfazed by what doesn’t conform to the perfection trajectory, ready to go on and do something different, to learn some new tricks.

Hospital error rates

Recognising imperfection means looking for and acknowledging errors. Drug errors in hospitals were for many years rated at 3 in every 1000 cases or 0.3%. With computerisation of drug prescribing, an early adopter hospital (a famous US hospital) used a computer to check individual drug prescriptions against the required protocols. The computer detected an error rate of over 3%, but these errors were different from the ones forming the 0.3%. The hospital decided to get to the bottom of this and put a team in various areas of the hospital for a month, painstakingly checking every prescription in tedious detail. They found an error rate of 5%, but the errors they found were largely different ones, making a total error rate of over 8%. The hospital now knew what mistakes were being made and did something about it. Other hospitals undoubtedly had similar error rates in practice, but carried on happily thinking theirs was 0.3%.

Which hospital would you prefer to be treated in?

It is not about slackness. It’s about being able to carry on efficiently and effectively when things aren’t perfect. It’s about adaptability and flexibility, and not being ground to a standstill because something didn’t quite work out or wasn’t expected, but taking that in one’s stride and moving forward along the right path.

The other positive side to recognising imperfection is that you are actually freed to do something before you are certain it is perfectly right. Good managers do things. Imperfect managers can do things. I received an email from a non-executive director who said, ‘The results reported at the board today are a clear demonstration that good things do not just happen – they are made to happen.’ What I have seen in failing organisations is an absence of the ‘making’.

‘Happening’ and ‘doing’

This contrast between ‘things happening’ and ‘management doing’ is illustrated repeatedly in revelations about insecure or lost data in many major organisations. For instance, an investigation by a senior city accountant into the loss of 25 million child benefit records, including bank details and sensitive personal information, by HM Revenue & Customs found ‘no visible management of data security at any level’ and officials demonstrating a ‘muddle-through ethos’.

What I noticed at Medway was that checks and balances, standards and competencies were being taken for granted. If something went wrong in a process, the error was reported, but the system that was supposed to pick up that error and then ensure its cause was found and corrected was no longer working properly; most importantly, there was no one there to monitor that it was no longer working properly. Mistakes weren’t being corrected and used to learn better behaviour. One minor failure had led to another, and another, and so performance had started to spiral downwards.

Once the behaviour of staff involved in these processes was understood and coordinated, something could be done about the problem. Those same staff had the necessary skills and could work out the answers; they just needed to be supported and given the right context. When action replaces muddle-through, you are on the road to solving your problems. As doers, managers can maximise their organisation’s achievements.

IDEA 4: EVOLVE AND ADAPT

- Living organisms evolve and adapt.

- They are sensitive to their ever changing environment.

- So are imperfect managers.

- They scrutinise the ground beneath their feet and the distant horizon – and everything in between.

- ‘Imperfect management’ provides the conditions for businesses and other organisations to live and do things better.

- It makes them thrive, hang together.

- It means they build up a resistance to all the things that create failure, and an ability to shake them off.

This idea is separate but it is also a completer. Self-correction, rebalancing, coping and fault tolerance are all possible and are all enhanced if you don’t unnecessarily make things worse. The virtue of a course of action needs to be balanced against its adverse consequences. Many managerial ideas only focus on their benefits. This can create a blinkered short-termism. The success happens, but who is around to account for the failure? This is true of the goals and ends of businesses but it is also true of what happens within them.

IDEA 5: AVOID BIG SHIFTS

- Avoid making quantum leaps for their own sake.

- They create risk and can destroy sound organic functioning – sometimes for ever.

- ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’

- Show some humility.

- See innovation as growth, building, not creative destruction.

- ‘Above all, do no harm’ – attributed to Hippocrates, father of medicine, and beloved of arguably the first real hospital manager, Florence Nightingale.

At the micro level, if you permit violence to be done to the values of a business, you start to degrade it, to make it lose its vitality and healthiness. This has dreadful consequences in the long term. If, for example, you sacrifice honesty and straightforwardness to achieve your ends, the business will cease to value these qualities and will forget about them, and it will suffer. If you see innovation as an unqualified good, something we have to do even though we don’t know what it is, and the status quo as dispensable, you may inadvertently, carelessly, destroy crucial aspects of the workings of your business. An insider in a once famous and FTSE top 100 electronics and IT company told me, ‘We innovated like crazy, and we went out of business.’

If you cut corners on safety or competence to achieve more, more quickly, then the lesser valuation of safety and competence will come back and hit you. You will have achieved something, but you will have done harm. To preserve the vitality of a business, its ability to come back to a happy resting point, its homeostasis, there needs to be a powerful bias towards these last two principles. It’s a bit like the centre of gravity: stray too far from it and you will fall over. If it is strong, it will pull you back to the right place.

Adapting

The fundamental difference between soundly functioning businesses and failing ones is coherence and unity on the one hand and fragmentation and insular behaviour on the other. So why one or the other? Is there a pattern? What is the glue that enables coherence?

The pattern I have found is of positive and negative change through time:

- either a failure to change and adapt to meet changing circumstances, often accompanied by a failure to recognise the need to adapt;

- or a more positive process of adapting, evolving, growing, and eventually, hopefully after a long period of survival and doing well, fading away and maybe disappearing.

Organic life survives and evolves by adaptation. Adaptation is itself a response to a failure, in order to deal with new circumstances. A failure to adapt is ultimately a death sentence for a species. The mutant, the adaptor, the extra evolved organism is the one that doesn’t fail or responds to the potential failure and moves on to success. And so it is with businesses, organisations and management.

Businesses or units within them can be quite small and apparently simple, possibly only a handful of people making and selling a single product. Even here, though, a business of any durability builds up experience, practice, competence and an ability to respond to the varied and unpredictable demands of everyday life. A business comes into being to meet a need, and if it does so successfully, then it thrives, flourishes and endures. It is a truism that businesses are at their most vulnerable when they are small, new to this world and, in varying degrees, naïve, innocent and inexperienced. If they don’t learn and develop fast, they run into trouble and fail; in all probability they cease to exist.

Now apply this very simple idea to the much larger businesses that typify the workaday world and in which most of us spend our working time. Bigger, established businesses comprise hundreds or thousands of people and will have been around for a fair while. The variety of skills, experience and understanding within them will be enormous and most of it will be located in the individuals who work there. It will be interconnected, interrelated, interdependent, because each particular understanding, expertise and experience will need to be complemented and validated by others, to add all the value it can to enable good products to be produced, to enable development to take place and to enable the business to react and grow.

To have a long, healthy life one needs to avoid illness, deal with it when it occurs and do what it takes to remain fit and healthy. This is management’s task in relation to the body of the business, the business organism. We need to know whether our business or our unit within it is healthy or not, what we need to do to make it healthy and thriving, how to recognise signs of ill health and how to do something about them before they become disabling and then fatal illnesses.

The business that achieved particular landmark success yesterday may be bankrupt today. Think of all the companies that have been swallowed up or disappeared. Look at:

- The shifting fortunes of computer companies, first impregnable IBM, then Apple, then Microsoft.

- The travails of Nokia, as its mobile phone market share and market leadership fell away at speed, heading towards Apple and Samsung.

- Kodak, the camera company, once synonymous with photographs and photography. It somehow missed out on the boom in digital photography despite helping to invent it, and declared itself bankrupt in January 2012.

- The ups and downs in the UK retail sector. Impregnable Marks & Spencer is down, then it’s up, then down again; Sainsbury’s similarly dips, and bobs up. Who would predict who’s next?

Each of these businesses survived and thrived for a long while, and those that remain can and should still do so, but their managers must be striving not just for success but to sustain what they do successfully over a long period to have any chance of this. And this means recognising that the complexity of ‘living’ businesses is critical. It means:

- realising complexity exists;

- realising it will have a logic and an order even if it is seemingly incomprehensible;

- absolutely not treating it as mistaken and misguided – that will almost certainly lead to destruction and loss;

- preferably, though not always necessarily, understanding the organisation’s logic;

- accessing it where possible;

- most importantly, utilising it and channelling it;

- in this way, creating health and development in the organisation;

- thereby solving the organisation’s problems; and

- where it is failing, setting it firmly on the path to recovery.

Although this whole account has a deliberately positive and constructive tone, the managerial watchword is vigilance. Remember, many of this book’s examples are from failing businesses. Growth and development based on deeply embedded understandings and processes can still get out of control and be destructive, just like the infections or cancerous growths within living bodies, and create failing businesses. Management needs to tap down to root behaviours, insights, experiences and skills, ensure they promote health, not dysfunction, and where organisational health has been lost, recover it.

Giving and receiving feedback

Businesses and individual work units within them are (obviously) made up of real people with real emotions, feelings, behaviours and skills. What, then, provides the essential link, the binding together between the overall living organism and the real people who must make it work? It is communication. It is more than overhearing something, or the wind whistling past. When we communicate we convey what we know, we share it, we open it up for scrutiny, we allow others to modify and improve it and vice versa, we work as a whole rather than a part, we are understanding and we are cooperative. A business which works well, which communicates and in which people communicate, conveys information and processes it effectively.

The importance of using feedback

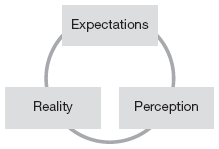

When I took over West Hertfordshire Hospitals its staff assumed they were doing what patients wanted, but surveys showed that to be far from the case: we were creating much higher levels of dissatisfaction than other hospitals because we were not communicating with our patients, or with each other enough, or well enough. As a result many things were being done without proper thought and many expectations were being defeated. When I realised this, I got the organisation to look through exactly what we were failing on, and how we were failing to communicate, reassure patients and often meet their very basic needs. The reaction of staff was very instructive. It wasn’t to say that none of this was true or that it was nothing to do with them. Instead they showed a huge determination to sort the problems out and proactively put in place systems to communicate with patients. Following directly from that response, a wide range of changes was brought in from the bottom up, using what staff knew and understood about patients. And at the heart of doing things better was consistent communication and taking responsibility for it. This is not just about uniting reality and perception. Here it means linking the perception and the reality to patients’ expectations.

Good processing and good processes drive businesses. These processes have feedback loops: they are being changed constructively and positively all the time by the people in them, alert to what is going on around them and what is being communicated to them (see the diagram on the next page). When communications fail or cease to take place, processes that need feedback and responsiveness become stuck, default and cease to work effectively. They cease to respond to the changing world around them. They help precipitate failure.

Different bits of the body, different organs, undertake different processes, all of which combine to create the final effect. They do this simultaneously – multi-tasking, if you like. Increasingly, we see computers being developed to do the same, though as yet in an infinitely simpler way. They receive information, compute it and place the results alongside other analytic and computational tasks that have been undertaken to result in a unified action. The functions of a nerve end, a cone in the eye, a tooth and a blood cell are utterly different but they combine to make the body work.

The communication-feedback loop

This process of cooperative differentiation is something to look for and applaud. It is not about demarcation. You only differentiate and do different things when it helps. But it is about skill and specialisation. And the more complex the task undertaken, the more one will be looking for effective cooperative differentiation and specialisation. Managed organisations can and should be understood and applauded in the same way.

Differentiation in London

While writing this book I came across Peter Ackroyd’s fascinating book, London: The Biography. One of the myriad insights in that book is that, as London grew and grew, it differentiated the skills of its citizens and made them much more particular than in smaller, simpler communities. This differentiation was part of what enabled London to grow and become more effective. This is how he puts it:

The segregation of districts within London, is also reflected in the curious fact that ‘the London artisan rarely understands more than one department of the trade to which he serves his apprenticeship’, while country workmen tend to know all aspects of their profession. It is another token of the ‘specialisation’ of London. By the 19th century the division and distinctions manifested themselves in the smallest place in the smallest trade … ‘the number of their branches and subdivisions is simply bewildering’; ‘a man will go through life in comfort knowing but one infinitely small piece of work’ … So these workers became a small component of the intricate and gigantic mechanism which is London and London trade.

Peter Ackroyd, London: The Biography

(Chatto & Windus, 2000), p. 126

Interestingly Ackroyd sees London on the one hand as a ‘mechanism’ but on the other as an organism; hence the expression ‘the biography’. Of course, London and the businesses I talk about are both mechanisms and organisms.

Managing relentlessly

The five ideas outlined at the beginning of this chapter can be used to pin down the ‘evolution vector’ which good, alert managers have, and with which they imbue their staff. Time and again in difficult situations, the managers who do well are not necessarily the cleverest people, and the management approaches that work are not the most sophisticated, but are those that keep going, come what may. The most robust technique is never to accept there is a brick wall, and to make each answer the springboard to solving the next question. It’s about saying two things together. This is good enough for now. It will never be good enough for good.

When I started working to reduce waiting lists at Medway, my team and I were pioneers. There was no guidance available from anyone on what we had to do. So we tried one thing, and then another. If something half-worked, we developed it; we looked for new ideas from the new ground we had secured. But we always kept the ground we had secured. At first slowly, but then more rapidly, we made progress. When we looked back on what we had achieved, we could see the pathway we had trodden, but while we were doing it we had effectively been slashing through the undergrowth blindfolded. That is what I call relentless management. It’s about trying things until they succeed and, as and when they do, building on them – endless iterations until a virtuous loop is created.

Relentless management isn’t a form of megalomania, trying to and assuming you control everything. It’s about:

- getting on top of a sufficient amount of what surrounds you to be able to act

- then acting

- reviewing that again, once you’ve reached some new, safer ground

- moving onto the next higher, safer bit of ground

- reducing the 20% error that had to be accepted today, by 80% tomorrow

- reducing the remaining 20% by 80% the day after that.

There will be a way through, even if it isn’t the one that seemed likely initially, and even if it entails unpleasant consequences.

This shows other keys to relentlessness: pragmatism, opportunism, lateral thinking, and quite simply admitting error and starting again in a different direction. Relentless management ensures your work is based on a convincing narrative drive that fits the facts and the needs. You don’t find out what story you are in, you choose to tell the story and help it unfold. So clear, well-thought-out, transparent systems and processes are essential aspects of thriving organisations.

- Relentless managers keep running. They know it’s a marathon but that there are odd, sometimes unexpected sprints while it takes place.

My team had reduced the number of outpatients at risk of waiting more than the target of six months to a trickle. But there was still a risk that we would not be able to see them all by the deadline. They managed to track most down and persuade them to come in. Some couldn’t be contacted. Members of the team went round to their houses, asking if they would be willing to come in at times that suited them. As they got closer to zero, it got more difficult. Patients couldn’t be bothered to change, didn’t want to, or simply objected to us badgering them. But as the team persisted, patients either said they didn’t now want to come at all or agreed to come to one of the clinics that had been put on. So, astonishingly, the target was achieved. It was an incredible team effort, in tracking down patients, thinking of alternative pathways for booking and treating them, and acting so quickly.

- Relentless managers never give up.

- They go for targets: they go beyond targets.

- They are determined and focused.

- They are always dissatisfied and always curious.

- They have a direction but they steer rather than are driven.

- They keep reviewing where they are going.

- What they are doing develops. It is a personal narrative that makes sense to themselves, the main actor, and to those following the narrative.

- They see brick walls as challenges. They are prepared to go around them, and on occasion to back away from them to make progress.

My team were within days of the target deadline. They had got all patients who needed to be operated on booked in – except one. Team members contacted him, cajoled him, offered practically any time or date before the date that would suit him, but he said it simply didn’t suit him and he would rather wait. In the normal sane, workaday world this would have been fine because this is what he wanted, but it would have breached the target with serious adverse consequences. The Medical Director offered to have a word with him. He said it would be very helpful to the hospital if the patient was able to come in before the deadline and asked if there was any chance of this. He also offered personally to operate upon the individual. The patient said, `Doctor, if it would be helpful, I would be happy to.’ He was operated on hours before the deadline.

- They are pragmatic about actions. They are willing to try anything.

- They’re respecters not breakers or avoiders of obligations and duties.

- They’re honest (because honesty underpins and gives momentum to drive) at the same time as they are pushy.

- They are scouts and foragers. Their antennae are always up.

- They are extractors, miners, diggers for information, and for answers. They dig till they find what they are looking for.

- They are joiners, catalysts, creators of chain reactions.

- They are orchestrators, jugglers, balancers.

- They see one problem solved as the springboard to sorting out the next one: ‘I’ve made a profit. How do I embed it? How do I increase it?’ ‘My school has achieved great exam results. How do I make sure that happens next year, and the year after and the year after that?’

Steve Jobs

When the late Steve Jobs returned as CEO of Apple in the late 1990s because the company was in deep trouble, he realised that Apple computers were regarded as a sort of evolutionary dead end, ignored by the masses, looked down on by the experts and revered only by a small group of ‘geeks’, principally in publishing, design and architecture. He began to change that, initially by creating the iMac computer, which looked attractive – sexy, see-through and colourful. And so Apple computers began to gain broader appeal.

But Jobs also realised that simplicity, functionality and, above all, meeting people’s most basic needs easily were what could give Apple an edge. With the iPod, Apple went to the front of the pack, creating a worldwide hit by meeting a simple, direct need of the everyman user. Next came the iPhone, then the iPad and so on and so forth. Apple has now become the universal purveyor of IT gizmos for us all. And it was all about relentlessness – starting from a difficult position, getting one thing right, then another, and then building on that, until finally the basic position has been turned round and there is a new platform for successfulness.

Relentlessness can bring connotations of pain and unpleasantness. To endure and thrive as a relentless manager, to really be one, you have to enjoy what you are doing, be animated by the effort and be enlarged by it. Because if you are not, then all those qualities outlined above will start to slip away and you will fail.

For me one of the best bellwethers of enjoyment is absorption in a task. We perform best when we are totally immersed, giving the task our all. This has been described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in his classic book Flow. This absorption is quite different from forgetfulness, inattention and blinkeredness, all of which I discussed when describing the warning signs of failure. This type of absorption is about focus, about bringing all one has to bear on the task in hand. It is the essence, the apogee of relentless management.

To sum up …

The way you achieve the opposite of failure, sustained successfulness as a manager, is by doing the following:

- adapting;

- using feedback;

- differentiating tasks and skills and then combining them to ensure delivery;

- internalising and using the five ideas;

- in particular, avoiding the delusive pursuit of perfection;

- instead, delivering and managing well but imperfectly.

In the following chapters, I will describe the skills needed and how to acquire them.