Colorado

GREAT SAND DUNES

ESTABLISHED 2004

Like a lost piece of the Sahara Desert that’s been dropped into a Colorado valley, the Great Sand Dunes, with their steep mountain backdrop, are equal parts baffling and beautiful.

When you first see the dunes, the obvious question is: how on earth did they get here? The tallest dunes in North America nestle between the San Juan and Sangre de Cristo mountains, the byproduct of a huge lake that once covered the San Luis Valley and later drained into the Rio Grande. A sand sheet was left behind when the lake disappeared, and prevailing winds blew the sand toward lower passes in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Frequent storms brought wind from the opposite direction, and the two opposing forces caused the sand to form vertical dunes. Vegetation across the valley floor has since slowed the process, but the landscape is far from static. Even today, parabolic dunes form in the sand sheet and migrate toward the dune field.

They might look barren, but the dunes support a surprising amount of life. Only the top few inches are dry; rainfall keeps the lower layers moist and allows hardy plants like Indian ricegrass, blowout grass, prairie sunflowers, and scurfpea to thrive, as well as animals such as salamanders, kangaroo rats, and tiger beetles. Beyond the dunes, there’s even more diverse flora and fauna in the park’s wetlands, lakes, rivers, and alpine tundra ecosystems.

150

The surface temperature of the sand in summer can reach 150°F (66°C).

–20

On a winter night, the temperatures can drop to lows of –20°F (–29°C).

Not just a story of unusual geology, the dunes are also a fabulous recreational area

Wild deer survive on plant life and scrub in the arid climate

Sandbox playground

Unlike many fragile natural environments, the dunes suffer no ill effects from being trampled, hiked across, and even sledded down. The Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve encourages visitors to rent special sleds or sandboards for surfing or sledding down the dunes. Of course, to come down, you first have to hike up, and this can feel like a Sisyphean task. There’s something deceptive about distance here—even the shorter, nearer dunes that look easy to reach can take surprising effort to climb. The payoff is the downhill spree.

If you prefer to travel both directions on your own two feet, you can reach Star Dune, the tallest in the park (and in North America), in about five hours round trip; find the trailhead by hiking 2 miles (3 km) south along Medano Creek to the dune’s base, then follow a ridge to the summit. With a permit, you can camp overnight—imagine the starry skies and nocturnal species you’ll see from a campsite.

Trails outside the dunes, such as the Mosca Pass Trail, provide a taste of the nearby landscape. A hike to Upper and Lower Sand Creek lakes starts north of the park boundary and visits two alpine lakes framed by 13,000-ft (4,000-m) peaks. The 8-mile (13-km) hike is a good place to spot pikas.

Kids in particular will enjoy splashing in Medano Creek, which flows from early spring into summer. Wading, swimming, tubing, and sand sculpting are all popular.

The Great Sand Dunes was named an International Dark Sky Park in 2019, and the nighttime stargazing is epic. Hike the dunes, too, under a full moon, when it’s so bright no flashlight is needed.

Like its winter counterpart sledding, sandboarding is a downhill speed thrill

Three Hikes

Montville Nature Trail ▷ 0.5 miles (1 km) round trip. An easy, shaded loop from the visitor center with views of the first row of dunes.

Wellington Ditch Trail 1.8 miles (2.9 km) round trip. Branching off from the Montville Nature Trail for another mile, this trail is good for spring wildflowers and dune views.

Mosca Pass Trail ▷ 7 miles (11 km) round trip. From a trailhead near the visitor center, this trail follows Mosca Creek through forest and meadows—an especially good place for spotting grouse, wild turkeys, and songbirds.

History of the San Luis Valley |

|

|

History casts a long shadow here: prehistoric Clovis and Folsom Complexes, the Ute, Spanish, and other Europeans have all made their mark. |

|

10,000 BCPaleo-Indians migrate to the valley, where they hunt the ancient bison and mammoths with spears launched with an atlatl (spear-throwing tool). |

|

5500 BCClimate fluctuation leads to population growth and technical innovations. Still nomadic, people experience greater stability in what is called the Archaic Stage. |

|

AD 900–1650The indigenous peoples are mostly Ute, who live in hunter-gatherer societies. Comanche, Apache, Navajo, Arapaho, and Cheyenne come to trade, hunt, and raid. |

|

1598After reports of gold in the San Luis Valley, Spanish explorer Juan de Oñate claims all land surrounding the drainage from the Rio Grande for Spain. |

|

1694Spaniard Don Diego de Vargas provides the earliest surviving written record of the area, detailing his encounters with the Ute and his wonder at bison herds. |

|

1807Army officer Zebulon Pike enters the San Luis Valley to explore the Southwest and the Spanish settlements in New Mexico. He spots the peak later named for him. |

|

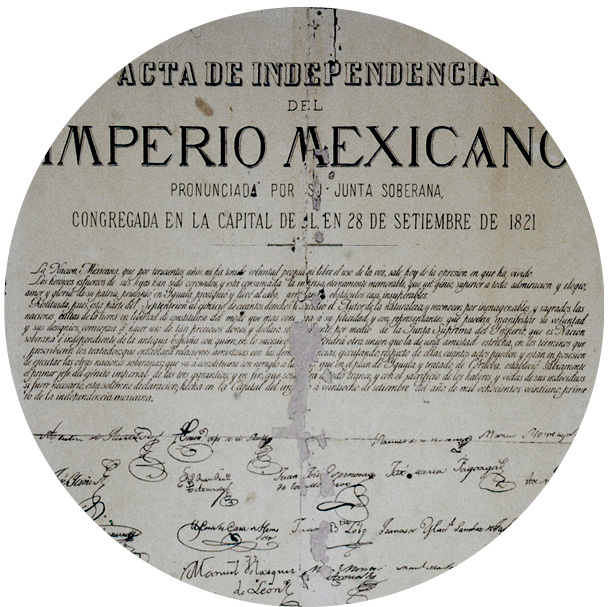

1821The Mexican War of Independence ends New Spain’s dependence on Old Spain, severing ties. The San Luis Valley is now fully part of the new nation of Mexico. |

|

1821–22Fur trader Jacob Fowler travels the valley observing the animal and plant life, white settlers, and American Indians. The New York Times reviews his published journal. |

|

1845–48The US annexes Texas, which achieves statehood. The San Luis Valley is part of the annexation. The Mexican-American war sees Mexico lose vast tracts of land. |

|

1876Within a month of the nation’s Centennial, Colorado becomes the 38th state in the Union. Known as the Centennial State, its territory includes the San Luis Valley. |

|

1876–79African American Buffalo Soldiers patrol the Great Sand Dunes area to keep peace between the settlers and Indian tribes, who coined the soldiers’ catchy moniker. |

|

1932President Herbert Hoover signs a proclamation giving Great Sand Dunes monument status. The status protects the delicate ecosystem from gold and silver mining in the area. |

|

2004The monument becomes the national park and preserve you see today, acquiring surrounding land to reach its current size of 168 sq miles (434 sq km). |

|

Sandy seascape

People have been interacting with this park long before it was a park—at least 11,000 years. Stone Age nomadic hunter-gatherers roamed the San Luis Valley, as evidenced by spearpoints used to hunt mammoths. More recently, Ute, Apache, and Navajo inhabited the area. The “living artifacts” of peeled ponderosa pines tell how they used bark for food and medicine. Spanish explorers arrived in the 1600s and 1700s, followed by Zebulon Pike (of Pike’s Peak) in 1807. Pike’s journals describe the appearance of the dunes as “that of the sea in a storm.”

The idllyic and aptly named Star Dune is a remarkable 750 ft (229 m) from base to summit

FLORA AND FAUNA

Tiger Beetles

Endemic to the park, the tiger beetle is a sand obligate that thrives in this protected habitat, hunting down ants, mites, and other beetles with amazing speed. Key markings are its iridescent green head and dark, violin-shaped pattern on the back.

A solitary camper leaves a footprint trail in the pristine sand