CHAPTER THREE

WHAT MAKES PUBLIC ORGANIZATIONS DISTINCT

The overview of organization theory in Chapter Two brings us to a controversy about what makes public organizations distinct. Leading experts on management and organizations have downplayed the distinction between public and private organizations as either a crude oversimplification or as unimportant (Fayol, 1917; Gulick and Urwick, 1937). In contrast, very knowledgeable people called for the development of a field that recognizes the distinctive nature of public organizations and public management.

This disagreement has major implications. A main rationale for privatization is that private organizations perform better. Privatization accounts for a significant portion of the world economy. On the other hand, its advantages over direct government provision are far from decided (Megginson and Netter, 2001). The absence of clear evidence in support of privatization has not dissuaded some representatives of the US Congress from wanting to privatize the National Park Service (NPS) to turn around the agency's budget deficit (Solomon, 2020).

Government officials around the world often consider questions about what should belong to the public and what is better off in the hands of business. President Donald Trump, e.g., pondered whether to auction off drilling rights in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Government officials in China are confronted with similar questions with regard to state-owned enterprises (SOEs). In general, SOEs are a type of hybrid organization; they carry out public tasks and have business-like characteristics, but they also have a greater level of autonomy from political principals, compared to what we think of as traditional government (Pollitt et al., 2004; van Thiel, 2012). SOEs are reportedly about 20% of the world's total stock market value (Musacchio et al., 2015).

This chapter discusses important theoretical and practical issues that fuel this controversy and develops conclusions about the distinction between public and private organizations. First, it examines the problems with this distinction. It then describes the overlapping of the public, private, and nonprofit sectors in the United States, which precludes simple distinctions among them. The discussion then turns to the meaning and importance of the distinction. If they are not distinct from other organizations, such as businesses, why do public organizations exist? Answers to this question point to the need for public organizations and their distinct attributes. How can we define public organizations and managers? This chapter discusses some of the debates over the meaning of public organizations and then describes the best-developed ways of defining the category and conducting research to clarify it. After analyzing problems that arise in conducting such research, the chapter concludes with a description of the most frequent observations about the nature of public organizations and managers.

The Generic Tradition in Organization Theory

A distinguished intellectual tradition bolsters the generic perspective on organizations, the position that organization and management theorists should emphasize the commonalities among organizations. They should develop knowledge applicable to all organizations, avoiding such popular distinctions as public versus private and profit versus nonprofit. As analysis of organizations and management burgeoned early in the twentieth century, leading figures argued that their insights applied across commonly differentiated types of organizations. Max Weber (1919) claimed that his analysis of bureaucratic organizations applied to both government agencies and business firms; however, he also considered the state as an entity that successfully claims “a monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory” (Water and Waters, 2015, pp. 129 et seq.). Frederick Taylor applied his scientific management procedures in government arsenals and other public organizations. Similarly, the emphasis on social and psychological factors in the workplace in the Hawthorne studies, McGregor's Theory Y, and Kurt Lewin's research pervades the organizational development procedures that consultants apply in government agencies today. James Thompson (1962), a leading figure among the contingency theorists, echoed the generic refrain – that public and private organizations have more similarities than differences. Herbert Simon, a leading intellectual figure of organization theory, assigned relative unimportance to the distinctiveness of public organizations. Simon's leading text in public administration contains a sophisticated discussion of the political context of public organizations (Simon, Smithburg, and Thompson, 1950). It also argues, however, that there are more similarities than differences between public and private organizations. His major work treated organizational processes as applicable to all organizations (e.g., Simon, 1948; March and Simon, 1958).

Findings from Research

Objections to distinguishing between public and private organizations draw on more than theorists' claims. Studies of variables such as size, task, and technology in government agencies show that these variables may influence public organizations more than anything related to their status as a governmental entity. These findings are consistent with the observation that an organization becomes bureaucratic, not because it is in government or business, but because of its large size.

As research on organizations burgeoned in the twentieth century, studies sought to identify organizational dimensions (typologies). However, efforts to produce measurable evidence (taxonomies) of distinctions were inconclusive. Haas, Hall, and Johnson (1966) measured characteristics of a large sample of organizations and used statistical techniques to categorize them according to the characteristics they shared. A number of the resulting categories included both public and private organizations. This finding is not surprising, because organizations' tasks and functions can have more influence on their characteristics than their status as public or private. A government-owned hospital, e.g., resembles a private hospital more than it resembles a government-owned utility. Consultants and researchers frequently find, in both the public and the private sectors, organizations with highly motivated employees as well as severely troubled organizations. They often find that factors such as leadership practices influence employee motivation and job satisfaction more than whether the employing organization is public, private, or nonprofit.

Pugh, Hickson, and Hinings (1969) classified fifty-eight organizations into categories based on their structural characteristics; they had predicted that government organizations in the sample would show more bureaucratic features, such as more rules and procedures, but they found no such differences. However, the government organizations did show higher degrees of control by external authorities, especially over personnel procedures. The study included only eight government organizations, all of them local government units with functions similar to those of business organizations. Consequently, the researchers interpreted as inconclusive their findings regarding whether government agencies differ from private organizations in their structural characteristics. Studies such as these have consistently found the public–private distinction inadequate for a general typology of organizations (McKelvey, 1982).

Sector Blurring: Hybrids, Agencies, and Quangos

The public sector is operated by the government and funded through tax dollars, and the private sector is run by individuals and business organizations for profit. As for the nonprofit sector (the voluntary sector), these organizations have a special status (often involving tax exemption) because they further a social cause.

At the same time, there are a number of challenges in drawing distinctions. Public and private sectors overlap and interrelate in a number of ways, and this blurring of sectors has advanced even further in recent years (Christensen and Lægreid, 2003; Heinrich, Lynn, and Milward, 2009; Verkuil, 2007), due to the increasing number of “hybrid” organizations in many nations.

Hybrid organizations are partially public and partially private. Authors refer to them with many different labels (Koppell, 2003). E.g., Greve (1999) notes that hybrid organizations collectively comprise the gray sector, while Van Thiel and van de Wal (2010) use the term parapublic sector. Other labels used in the literature include semi-autonomous agencies, statutory bodies, statutory companies, statutory authorities, independent regulatory authorities, executive agencies, and bureaus, as well as various nation-specific labels. The label “agencies” is used more in nations other than the US, while “hybrids” is more prominent in US-based scholarship, in which “governmental agencies” is the term used to describe traditional governmental units, especially at the federal level.

Hybrids make up a substantial portion of the population of organizations and conduct much of the government's business in developed and emerging economies. Although precise estimates are difficult to make, some experts indicate the sector is equal to or larger than the core government bureaucracy both in terms of personnel and budget (e.g., van Thiel, 2020). Governments rely on these organizations to carry out important public services, such as financing mortgages and student loans. Hybrids have come to dominate some markets, such as federal housing market, in the case of Freddie Mac, and student loans in the case of Fannie Mae in the United States. When they face a crisis, the effects can be very wide reaching (Labaton and Andrews, 2008).

Definitions and Characteristics. To untangle these concepts, one can look to a definition by an expert. Sandra van Thiel defines agencies as “organizations that carry out public tasks at arms' length of the government in a relatively autonomous way” (van Thiel and Yesilkagit, 2014, p. 319; see also van Thiel, 2012). Yet, the labels and definitions also vary by sector, discipline, and country. Minkoff's (2002) study of nonprofits refers to the emergence of hybrid organizational forms that combine service and political action. In the tradition of economics, Menard (2004) refers to the “collection of weirdos” that are neither markets nor hierarchies (p. 3). In the US context, Koppell (2003) defines a hybrid organization as “an entity created by government to address a specific public policy purpose, which is owned in whole or in part by private individuals or corporations and/or generates revenue to cover its operating costs” (p.12). Skelcher and Smith (2015) suggest hybridization arises from a plurality of rationalities and different institutional logics, which has held back theory development (p. 434).

Another approach to understanding semi-autonomous agencies/hybrids is to compare them to government bureaucracies. The following list is adapted from literature on comparing agencies to government bureaucracies (Pollitt, 2004; Pollitt and Talbot, 2004; van Thiel, 2012; van Thiel et al., 2012; Verhoest et al., 2012):

- Agencies carry out many of the same tasks as government bureaucracies, such as implementing policy and monitoring regulatory compliance.

- Agencies are subject to a less political influence compared to government bureaucracies.

- Agencies have a greater autonomy in policy-making and management decisions compared to government bureaucracies.

- Agencies are structurally disaggregated from their parent unit of government, as in the case of a “ministry,” but are still under some formal control of the parent unit. In other words, they operate at “arm's length.”

- Agencies vary in their permanence but generally are more permanent than an advisory committee and less permanent than government bureaucracies.

Origins. Many Nordic countries have used hybrid agencies to carry out public tasks for centuries (Greve, Flinders, and van Thiel, 1999; Wettenhall, 2005). These organizations were further emphasized in New Public Management reforms (Christensen and Lægreid, 2003; van Thiel, 2006). NPM doctrine considered traditional government bureaucracies inefficient and bogged down with red tape. NPM advocates called for a more businesslike government, more responsive to “customers,” more innovative, and more driven by outcome and performance. Advocates believed government would improve by relying more on the private sector, e.g., by outsourcing public services or by decoupling agents from principals (Boukaert, Peters, and Verhoest, 2010) and unbundling government (Pollitt and Talbott, 2004).

Hybrids and agencies also vary in purpose. Table 3.1 provides a few examples of the many motivations for the formation of hybrids and agencies.

TABLE 3.1 EXPLANATIONS FOR HYBRID ORGANIZATIONS

| Motivations for Creating a Hybrid. Use as a policy tool… |

Example |

|---|---|

| To save company too big or too strategic to fail | New Zealand rescue of Air New Zealand to support tourism industry |

| To maintain jobs or to aid a company in distress, that if left to fail will have negative consequences on the larger economy | The US bailout of General Motors, Chrysler in 2008 to avoid loss of over one million jobs and save auto industry National Coal Board in UK and comparable rescue operations in West Germany, Belgium, and Japan |

| To jumpstart investment and compensate for lack of private investment | Singapore investments in government-linked corporations to jumpstart the economy after the country gained its independence (1965) |

| To leverage state powers to provide public goods to benefit all individuals | Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) created in 1933 as a federally owned corporation to supply electricity and other services to rural areas. TVA was authorized by US government to take private property and justly compensate in order to provide service (eminent domain). |

| To increase access to public services by requiring reduced prices to targeted groups as a means of making certain services more affordable for the public's cross-subsidization | Cambodia Phnom Penh Water uses government cross-subsidies to distribute water below production costs to domestic households. |

Researchers have attempted to further classify semi-autonomous agencies to understand their differences. E.g., van Thiel and her colleagues have developed a classification based on a 30-country comparison of formal legal features, based on level of autonomy and level of control (Table 3.2).

When services are assigned to semi-autonomous organizations, the accountability relationships shift; there is a tendency to shift away from a relationship between elected politicians and citizens to a relationship between politicians and managers (Romzek, 2000; Grossi and Thomasson, 2015). Semi-autonomous organizations are sometimes the subject of controversy because they do not operate in a sufficiently businesslike fashion while showing sufficient public accountability. The United States Post Office (USPS) is one such example.

TABLE 3.2 AGENCIFICATION TYPES

| Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Type 0 | Unit or directory of national central or federal government (not state or local government) | Ministry, Department, Ministerial Directorate, Directorate General (DG), state institution |

| Type 1 | A semi-autonomous unit within the government, without legal independence but some managerial autonomy | Next Steps Agencies (UK); contract executive agencies (NL, B, AUS, IRL) most Scandinavian ‘agencies’; the German indirect administration, Italian Agenzia Service Agency (A); central bureaus (Hungary); state institutions (EST) |

| Type 2 | A statutory body, with legal independence, based on statutes, legal autonomy based on public or private law | Non-Departmental Public Bodies (NDPB; UK); ZBOs (NL); public establishments (IT, POR); parastatal bodies (B); statutory bodies or authorities (not corporations; A, EST, AUS, ILR, POR); indirect agencies (GER) |

| Type 3 | Private or private-law-based organizations established by or on behalf of the government; government owns majority or all stock, otherwise category 5 | Commercial companies, state-owned companies (SOC), state-owned enterprises (SOE), government foundations |

| Type 4 | Execution of tasks by regional or local bodies, and or governments (county, province, region, municipality) created through decentralization delegation or devolution | Lander (GER), regions (B, I, UK), states (AUS), cantons (CH) |

| Type 5 | Other, not listed above | Contracting out, privatization with government owning minority or no stock |

Adapted from typology developed by van Thiel (2012) and from Verhoest, Van Thiel, Bouckaert, and Lægreid

In August 2020, the United States Post Office (USPS) was thrust into the headlines when President Donald Trump opposed providing it with any further government funding. The USPS was at the same time criticized for not generating enough revenue (an expectation of business) and not prioritizing the delivery of mail-in ballots to voters (an expectation of the public). According to the Washington Post, without additional funding, the USPS would be unable to deliver millions of mail-in ballots in time for the election (Cox et al., Aug 14, 2020). Headlines from the Atlanta-Journal Constitution and the Los Angeles Times suggested that Trump wanted to block Postal Service funding to undercut mail-in voting (August 13, 2020). The alleged effort to make it harder for millions of voters to vote is a serious concern. Even more important is the question of whether the USPS should be subject to the political influence of politicians. The USPS is constituted as a government corporation. Should the US government be required to fund the USPS? Or, should the USPS be required to make a profit and therefore not rely on government funding? These questions are typical for hybridized corporations.

Answers to these questions are not clear. As a hybrid organization, the USPS faces the obligations of both a business and a public organization. Some analysts point out that USPS lacks a transparent ownership structure and is not subject to standard policies that apply to corporations. Like a commercial enterprise, the USPS has sources of revenue, including sales of stamps, money orders, and shipping supplies. Yet USPS is also required to provide universal service. This requires delivery to rural and sparsely populated areas, which is not cost-effective and profitable. USPS faces competition from private carriers such as FedEx and UPS, but none of its competitors are legally obligated to deliver mail to all parts of the US. The USPS cannot raise rates without the express approval of the Postal Regulatory Commission, a government commission that oversees postal rates and that can approve or deny them. Meanwhile, FedEx and UPS are powerful political donors, alleged to have “worked to keep the postal services offerings in the parcel and express delivery markets as noncompetitive as possible” (Shaw, 2006, pp. 112–113). At the same time the USPS has many special privileges, including sovereign immunity, eminent domain powers, an exclusive legal right to deliver first-class and third-class mail, and a statutory monopoly on access to letter boxes. It is also not subject to antitrust violations. The USPS illustrates the complex status of hybrid organizations, and the advantages and disadvantages that status can convey.

While not usually considered “hybrids” in their ownership and legal status, many nonprofit or third sector organizations, like government agencies, have no profit indicators and often pursue social or public service missions, at times under contract with the government. To further complicate the picture, experts on nonprofit organizations express concerns about their “commercialization,” by which nonprofits try to make money in businesslike ways. This may jeopardize their public service mission. Finally, many private for-profit organizations work under contracts or partnerships with governments in ways that blur the distinction between them (Zhang and Guo, 2020). Some corporations, such as defense contractors, for decades have received so much funding and direction from government that some analysts equate them with government organizations (Weidenbaum, 1969).

Functional Analogies: Doing the Same Thing. Obviously, many people and organizations in the public and private sectors perform virtually the same functions. General managers, secretaries, computer programmers, auditors, personnel officers, maintenance workers, and many other specialists perform similar tasks in public, private, and hybrid organizations. Organizations located in the different sectors – e.g., hospitals, schools, and electric utilities – also perform the same general functions. The New Public Management movement that spread through many nations in recent decades proposed that governments should use procedures similar to those purportedly used in business (Ferlie, Pettigrew, Ashburner, and Fitzgerald, 1996; Kettl, 2002; Lapuente and Van de Walle, 2020; Li and Chung, 2020; Hood, 1995; Hood and Peters, 2004).

Complex Interrelations. Government, business, and nonprofit organizations relate in elaborate ways (Kettl, 1993, 2002; Weisbrod, 1997; Cheng 2019). Governments buy products and services from nongovernmental organizations. Through contracts, grants, vouchers, subsidies, and franchises, governments arrange for the delivery of healthcare, sanitation services, research services, and other services by private organizations. These relations complicate the question of where government and the private sector begin and end (Jung, Malatesta, LaLonde, 2018). Banks process loans provided by the Veterans Administration and receive Social Security deposits electronically for Social Security recipients. Private corporations handle portions of the administration of Medicare by means of government contracts, and private physicians render most Medicare services. Private nonprofit corporations and religious organizations operate facilities for the elderly or for delinquent youths, using funds provided through government contracts and operating under extensive government regulation. Private businesses and nonprofit organizations become part of the service delivery process for government programs and blur the public–private distinction. Chapters Four, Five, and Fourteen provide more detail on these situations and their implications for organizations and management.

Analogies from Social Roles and Contexts. Government uses laws, regulations, and fiscal policies to influence private organizations. Environmental protection regulations, tax laws, and equal employment opportunity regulations either impose direct requirements on private organizations or establish incentives to get them to act in accordance with government policies. Here again, nongovernmental organizations share in the implementation of public policies. They become part of government and an extension of it. Even working independently of government, business organizations affect the quality of life in the nation and the public interest. Members of the most profit-oriented firms argue that their organizations serve their communities and the well-being of the nation as much as governmental organizations do. According to some critics, government agencies also sometimes behave too much like private organizations. Some critics of government laments the influence that interest groups wield over public agencies and programs. According to the critics, these groups use the agencies to serve their own interests rather than the public interest.

The Importance of Avoiding Oversimplification

Theory, research, and the realities of the contemporary political economy show the inadequacy of simple distinctions. Theory and practice must avoid oversimplifying distinctions between public and private.

That advice may sound obvious enough, but violations of it abound. During the intense debate about establishing the Department of Homeland Security, a Wall Street Journal editorial warned that the federal bureaucracy would be a major obstacle to effective homeland security policies. The editorial repeated simplistic stereotypes about federal agencies that have prevailed for years. The author claimed that federal agencies steadfastly resist change and aggrandize themselves by adding more and more employees. E.g., the increase in privatization and contracting has led to increasing controversy over whether privatization proponents have made oversimplified claims about the benefits of privatization, with proponents claiming great successes (Savas, 2000) and skeptics raising doubts (Verkuil, 2007; Megginson and Netter, 2001).

Clear demarcations between the public and private sectors are impossible, and oversimplified distinctions between public and private organizations are misleading. We still face a paradox, however, because scholars and officials make the distinction repeatedly in relation to important issues, and public and private organizations do differ in some obvious ways. Can we clarify the similarities and differences?

Public Organizations: An Essential Organization/Distinction

If there is no real difference between public and private organizations, can we nationalize all industrial firms or privatize all government agencies? Private executives in the US earn massively higher pay than their government counterparts. The financial press regularly lambasts corporate executive compensation practices as absurd, claiming they squander billions of dollars. Can we simply put these business executives on the federal executive compensation schedule and save money for these corporations and their customers? Such questions make it clear that there are some important differences in the administration of public and private organizations. Scholars have provided useful insights about the distinction, and researchers and managers have reported more evidence of the distinct features of public organizations.

The Purpose of Public Organizations

Why do public organizations exist? We can draw answers to this question from both political and economic theory. Even some economists who strongly favor free markets regard government agencies as inevitable components of free-market economies (e.g., Downs, 1967).

Politics and Markets. Decades ago, Robert Dahl and Charles Lindblom (1953) provided a useful analysis of the raison d'être for public organizations. They analyzed the alternatives available to nations for controlling their political economies. Two alternatives are political hierarchies and economic markets. In advanced industrial democracies, the political process involves a complex array of contending groups and institutions that produce a complex, hydra-headed hierarchy. Dahl and Lindblom called this a “polyarchy.” Such a politically established hierarchy can direct economic activities. Alternatively, the price system in free economic markets can control economic production and allocation decisions. All nations use some mixture of markets and polyarchies.

Polyarchy draws on political authority and can serve as a means of social control. It is cheaper to have people willingly stop at red lights than to work out a system of compensating them for doing so. Markets have the advantage of operating through voluntary exchanges. Producers must induce consumers to engage willingly in exchanges with them. They have the incentive to produce what consumers want, as efficiently as possible. This allows freedom and flexibility, provides incentives for efficient use of resources, steers production in the direction of consumer demands, and avoids the problems of central planning inherent in a polyarchy. The term invisible hand refers to a well-functioning market, when consumer demand equals the supply of a good or service (equilibrium). However, imperfections in the exchange process between buyers and sellers arise under certain conditions, leading to market failures, wherein markets allocate resources inefficiently and government intervention may be required to improve social welfare (Lindblom, 1977; Downs, 1967).

Limited number of buyers and sellers. In the ideal competitive market, sellers have an incentive to produce goods and services of acceptable quality at a cost that consumers will pay. If the seller fails to do so, buyers find a different source. However, a limited number of sellers or buyers prevents the equilibrium between supply price and demand price. When competition among sellers is limited, as was once the case of the single seller of telephone service – the AT&T monopoly, prices are unconstrained. Similarly, when there is a dominant buyer in the exchange relationship, that buyer, called a monopsony (often a large employer) can control the market. Studies have shown the unrestrained market power of several school districts in Missouri. Teachers had little mobility across districts and the district could dictate employment terms (Ransom and Sims, 2010). There is a growing body of evidence on the ways that dominant employers can suppress wages and benefits, and even compromise workplace safety (Azar et al., 2017; Jamieson, 2014; Kruegar and Ashenfelter, 2017). Employers in the meatpacking industry have been subject to this criticism due to the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 virus on its workers (Dorning, 2020).

Public goods and free riders. A public good is nonrival and nonexcludable. Nonrival means that consumption of a good or service by one party does not prohibit consumption of the same good or service by another party. When one person uses the internet, other parties are not prohibited from visiting the same website at the same time. In contrast, a candy bar is a rival good; when one person consumes a candy bar, other persons cannot consume the same candy bar. Nonexcludable means nonpaying consumers cannot be prevented from accessing a good or service. Certain services, such as national defense, have this public good characteristic. Once provided, national defense benefits everyone, even free riders. In contrast, a good is excludable if suppliers can prevent consumers from accessing it. E.g., subscription services are intended to make magazines excludable to nonpayers. Private companies will not be able to make a profit if many people can get their goods or services for free. In that case government might require payment by taxpayers and either subsidize production or provide the good or service itself.

Information asymmetry. When one party in the exchange has an information advantage, exploitation can occur. People often lack sufficient information to make wise individual choices in some areas, so government regulates these activities. E.g., most people would not be able to determine the safety of particular medicines, so the Food and Drug Administration regulates the distribution of pharmaceuticals. The lemon problem refers to the classic problem of information asymmetry in the market for used cars. In such a situation the sellers know more about the car than the buyers. As a result, buyers may unknowingly purchase defective cars (lemons) at a higher price than they would otherwise pay if they had complete information on the car's condition. To correct this problem, government may require full transparency on the part of the seller or require the seller to provide a warranty.

Externalities or spillovers. Some costs may spill over onto people who are not parties to a market exchange. Externalities can be negative or positive. Externalities cause market inefficiency because the price of the good or service does not reflect the total societal costs or benefits. As a result, organizations will overproduce or underproduce, depending on the nature of the externality. The classic example of a negative externality is pollution. A manufacturer polluting the air imposes costs on others that the price of the product does not cover. In the case of negative externalities, the government role may be able to regulate pollution or to tax or fine companies who pollute. The Environmental Protection Agency regulates environmental externalities of this sort. Education is considered a positive externality because its benefits are shared. Vaccines are also a positive externality because each vaccine has a spillover advantage for even those not vaccinated. In the case of positive externalities, the role for government may be to offer tax breaks or other incentives to encourage production to provide positive effects for a community.

Because of market failures, private sector solutions are not always the most efficient alternatives, although advocates of outsourcing and privatization assume they are. We cannot expect markets to deliver goods efficiently if competition is limited, if consumers do not have information necessary to make wise choices, if services can be obtained without paying, or if costs affect those outside of a transaction. At the same time, it becomes clear that government can play an important role in influencing markets to improve efficiency.

Government may act to correct problems that markets themselves create or are unable to address – monopolies, the need for income redistribution, and instability due to market fluctuations – and to provide crucial services that are too risky or expensive for private competitors to provide. Critics also complain that market systems produce too many frivolous and trivial products, foster crassness and greed, confer too much power on corporations and their executives, and allow extensive bungling and corruption. Public concern over such matters bolsters support for a strong and active government (Lipset and Schneider, 1987). Conservative economists, however, argue that markets eventually resolve many of these problems and that government interventions simply make matters worse. Advocates of privatization claim that government does not have to perform many of the functions it does and that government provides many services that private organizations can provide more efficiently. Ongoing controversies over such decisions play out in virtually all nations.

Political Rationales for Government. A purely economic rationale ignores the many political and social justifications for government. Government in the United States and many other nations exists to maintain systems of law, justice, and social organization; to maintain individual rights and freedoms; to provide national security and stability; to promote general prosperity; and to provide direction for the nation and its communities. In spite of the blurring of the distinction between the public and private sectors, government organizations in the United States and many other nations provide services that are not exchanged on economic markets but are justified on the basis of general social values, the public interest, and the politically imposed demands of groups.

Government Organizations as Distinct Actors

In the United States there is an interesting concept called the State Action Doctrine, which draws a line between public and private conduct. The State Action Doctrine also has important implications for public managers, government employees, and citizens, as well as for outsourcing and privatization.

Understanding the State Action Doctrine requires us to think about the purpose of the US Constitution. As introduced, the US Constitution sought to create a government that did not infringe on the rights of private individuals. It restricted the reach of government, not of private organizations (and individuals), in order to protect individual freedom. The Founders believed that other laws, including statutes and case law, would constrain private organizations; this was not the job of the US Constitution. Later, the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted to ensure that states (an arm of government) would not deprive individuals of due process or deny people equal protection. But again, the restriction applied to government. Thus, the State Action Doctrine, which ensures certain protections of the Constitution, such as the First and Fourteenth Amendment, only applies to the coercive power of the government against the individual, rather than the coercive power of the individual against the individual (Verkuil, 2007).

The concept is important to research and practice for several reasons. Consider the choice between government and a private company for the delivery of public service. Employees of these organizations perform similar tasks. Yet, government employees who might be terminated have recourse, in the form of due process. Employees of private organizations, including nonprofits, usually do not. There are many examples of such rights being applied differentially. For example, a person terminated for her sexual orientation is not automatically guaranteed due process if he or she works for a nonprofit organization. Rosenbloom and Piotroski (2005) discuss the case of the firing of a nonprofit's employee because she wore a T-shirt that proclaimed her sexual orientation. The government had contracted with a nonprofit to provide youth services. The same person could not be fired from a public organization without due process. The burden of proof would be quite high if a government had terminated the employee; the state would have to establish that the employee's sexual orientation interfered with her ability to perform her job.

A similar rights differential arises between citizens who receive public services from a public organization and customers who receive the same service from a private organization. In a case before the US Supreme Court, Jackson v Metropolitan Edison, a customer sued a private utility company when the company terminated her service without notice. The US Supreme Court ruled against the woman and in favor of the utility. According to the Court, running a utility is not an activity that has been traditionally and exclusively in the province of government. Thus, if there is no state action, due process is not required. Some utility companies are run by cities. For many years, the city of Vineland, New Jersey, operated Vineland Electric Company. Before a city-run electric company can terminate service, it must provide notice and a hearing.

Other examples abound. If a mayor or other elected official or a public manager discriminate on the basis of race, such conduct denies equal protection guaranteed by the Constitution. But if a private company discriminates on the basis of race, equal protection does not apply as the source of protection against discrimination. Similarly, employees who work for a public university cannot be terminated for their speech so long as that speech is protected by the First Amendment; however, absent other applicable law, this same protection does not apply for the same speech at a private university. This does not mean that legislatures cannot adopt statutes that regulate private behavior; they often do. It only means the Constitution does not establish the boundaries of some behavior. E.g., Congress adopted the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which says that private employers cannot discriminate on the basis of race. States and local governments have also passed various anti-discrimination laws regulating private behavior. These laws prohibit private employers from discriminating, not the Constitution.

The Court has applied narrow exceptions, but all were prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Notably, these exceptions have a historical context that involves what might be considered instances when public values were at stake. One exception involves a public functions test. Specifically, if a private entity is performing a task that has been traditionally and exclusively performed by government, the Court has broadened the scope of the State Action Doctrine, thus extending constitutional guarantees in private instances of state action. The often cited case is Marsh v Alabama, which involved a company that literally owned an entire town. Jehovah's Witnesses wanted to distribute their literature in the town but the company prohibited it, taking the position that the First Amendment does not apply to private property. The Supreme Court ruled against the company, reasoning that the act was a state action because running a town is a public function, that is, a function that has been traditionally and exclusively done by the government. Another example involves Texas voting laws. In the early part of the twentieth century, Texas refused to allow African Americans to vote. When the state was ordered to allow African Americans voting rights, Texas did not comply but instead decided political parties, not the state, would hold political primary elections, essentially arguing that political parties could not be required to enfranchise African American voters. The Supreme Court held that elections, including primary elections, are functions traditionally and exclusively performed by the government. Therefore, a private organization performing the function is state action and constitutional guarantees apply.

To make informed decisions on outsourcing, public managers should understand the rights and responsibilities afforded to state actors and non-state actors. Government frequently contracts with private companies to run many jails and prisons, as well as for prison transport and even work release programs. In general, private companies do not have to comply with the Constitution, which has obvious implications for the potential violations of inmates' rights or the rights of a recent parolee.

A number of significant contemporary debates also could turn on applications of the State Action Doctrine. E.g., citizens have expressed increasing concern about the disenfranchisement of voters. The State Action Doctrine raises questions about which aspects of an election are subject to state action and which aspects are not subject to state action. As another example, consider the recent controversy that social media giant Twitter ignited when the company removed President Trump's account from its platform. President Trump viewed Twitter's decision as a violation of his First Amendment right to free speech. On the other hand, Twitter defended its action, in part, by maintaining that as a private company it does not have to provide the rights afforded by the US Constitution.

Inherently Governmental Policy

Inherently governmental policy is another way in which public–private distinctions can influence public management research and practice. Federal law (The Federal Activities Inventory Reform or “FAIR Act of 1998”) and federal policy (Office of Management and Budget Circular A-76 or “OMB A-76”) require certain functions to be performed by government personnel and not by private nongovernmental employees. E.g., only government personnel are authorized to establish policy; a nongovernmental employee or contractor can implement policy but not establish it. Similarly, there is a difference between providing advice and recommendations, often done by contractors, and deciding what advice to accept or to reject, which is left to government. Other examples of activities reserved for government include conducting foreign relations, directing the military, controlling prosecutions, and directing criminal investigations. The OMB considers such activities so intimately related to the public interest that they require performance by government employees.

As a US federal agency, the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) must follow OMB-76. According to Dan Gordon, former administrator of the OFPP under President Obama, determining what is inherently governmental is not always clear-cut. Gordon devised criteria used by US agencies officials to test questionable cases. One such test concerns the unauthorized delegation of control. A contractor, for instance, cannot be authorized to exercise sovereign powers of the United States, as in entering into a treaty with another country on behalf of the US. The use of Acquisition Letters is another way federal agencies provide guidance on what is inherently governmental. Acquisition Letters are issued under the authority of the agency's senior procurement executives and go a step further than OMB Circular A-76; they provide illustrative lists of functions considered to be “inherently governmental” and lists of functions “closely associated with the performance of inherently governmental.” E.g., Policy Letter 11–01 explained what agencies must do when work is closely associated with inherently governmental functions. It required agencies to identify critical functions and to ensure they had sufficient internal capabilities to sustain the agency's mission. It also outlined agency management responsibilities to strengthen accountability for effective implementation of these policies. E.g., the agency is advised to limit or guide contractors' exercise of discretion by contractually establishing specified ranges of acceptable decisions and conduct.

Public Value and Public Values

In intellectual activity related to analyzing public organizations, authors have developed two related but distinct concepts: public value and public values (Fukumoto and Bozeman, 2019, p. 635). Both concepts receive scholarly attention and are now part of the curriculum at top universities, including the Kennedy School at Harvard.

Public value is an approach to public management that grew out of the work of Mark Moore, and what has become known as Harvard's Kennedy Project (Moore and Khagram, 2004). Moore's book, Creating Public Value (1995), is the publication most frequently cited by other authors. Moore “lay[s] out a structure of practical reasoning to guide managers of public enterprises … [in creating] real material value” (p. 1). The concepts of value and authority are key in Moore's concept of governance. Public managers who understand value and authority can be confident in and active in achieving the public interest (Prebble, 2018, p. 104). Moore contends that public managers create public value when they produce outputs for which citizens express a desire. Specifically,

“value is rooted in the desires and perceptions of individuals—not necessarily in physical transformations, and not in abstractions called societies…. Citizens' aspirations, expressed through representative government, are the central concerns of public management….” (p. 52)

Since public value depends on public authority, public managers need more than the skills taught in business schools; public managers need the know-how to interact with the authorizing environment. Moore further suggests that the legitimacy of government authority depends on whether management actually meets citizens' expectations. Specifically,

“… Every time the organization deploys public authority directly to oblige individuals to contribute to the public good, or uses money raised through the coercive power of taxation to pursue a purpose that has been authorized by citizens and representative government, the value of that enterprise must be judged against citizens' expectations for justice and fairness as well as efficiency and effectiveness.” (p. 52)

In 2003, Moore introduced a public value scorecard, an adaptation of the well-regarded Balanced Scorecard (BSC) by Kaplan and Norton (1992). In general, the BSC is a tool used by company managers to track staff activities and their consequences. The BSC is also considered a performance management orientation that focuses managers on a set of measures to monitor performance against objectives. Moore's version makes the BSC relevant to nonprofit managers by providing a three-pronged focus called a strategic triangle. Some thirteen years later, Mark Moore elaborates on the strategic triangle in Recognizing Public Value (2013). More specifically, the strategic triangle is used as a heuristic to guide practical reasoning on the part of public and nonprofit managers. The triangle urges managers to manage up to the formal authorizing environment. Managers accomplish this by identifying the sources of legitimacy and support that authorize the organization to sustain action needed to create value. Managers are encouraged to manage outward by involving the public and other stakeholders. They manage down to secure the operational capabilities the organization will rely on, or have to develop, to achieve the desired results.

Kelly et al. (2002) apply Moore's concept outside the US setting. Drawing on surveys from the United Kingdom and Canada about what citizens expect from their government, they propose a model that more explicitly includes a role for politicians. These authors conceive of public value as created by government through services, laws, regulations, and other activities. According to Kelly et al., citizens' preferences are not fully informed, so political officials shape citizens' preferences. In other words, citizens' preferences are expressed and mediated by elected politicians. Kelly et al. acknowledge the gaps in understanding how to create value, but they still emphasize the ongoing dynamic between citizens' conceptions of public value and government policy, which in turn creates outcomes that reflect public value.

Bozeman proposes the concept of “public value failure” in Public Value Failure: When Efficient Markets May Not Do (2002). Bozeman defines a public value failure as the gap between citizens' preferences and public policy. E.g., public opinion strongly favors gun control but no such policies are enacted, so the disjunction between public opinion and policy outcomes fails to maximize public values about democratic representation. As another example, the public and private sectors may produce a situation involving threats to human dignity and subsistence, such as an international market for internal human organs leading impoverished individuals to sell their internal organs merely to survive.

Jupp's and Younger's Accenture Public Sector Value Model (2004) explains that public value emerges from the production of outcomes of governmental activities, considered together with the cost-effectiveness of producing those outcomes. According to this model, “outcomes” are a weighted basket of social achievements. And, “cost-effectiveness” is defined as annual expenditure minus capital expenditure, plus capital charge (p. 18). In 2006 Accenture began the Institute for Public Service Value (IPSV) to explore how public value is created in government organizations. Among many other studies, IPSV conducted the Global Cities Forum in 2007–2009, which facilitated citizens' deliberations on their experiences and expectations of public value in 17 cities around the world.

As Moore's work gained prominence, some authors have given the concept of public value the status of a paradigm, while others have noted theoretical shortcomings. Stoker (2006) describes “public value management” as a paradigm that has emerged to solve the dilemma of balancing democracy and efficiency. Likewise, Christensen and Lægreid (2007) suggest that public value is a reaction to businesslike practices and strategies associated with NPM that have taken hold in Britain and New Zealand. Kelly and his colleagues (2002) offer a different description, yet one that also acknowledges an often-heard criticism of NPM, about its insufficient emphasis on democratic values. They regard public value as a performance measurement framework that includes additional dimensions of government's impact to add to the dimension of efficiency (Kelly et al., 2002, p. 35).

Some scholars acknowledge the gaps in public value theory and suggest corrective paths. Prebble (2019) describes the state of research this way: “Just as it matters that physicians have a workable theory of the chemistry of the human body, so it is important that public managers can assess a coherent philosophy about the use of public authority.” Prebble suggests a problem in Moore's treatment of “the public” as a concept. Moore's approach does not accommodate multiple and contrasting views of the public but rather treats the public as a whole. Prebble claims one cannot investigate the dynamic interactions between the use of public authority and public preferences if what the public values is ambiguous. This creates a practical problem for practitioners who aim to create public value and holds back theory development (p. 104). Fukumoto and Bozeman (2019) also assess the current state of public value theory and what obstacles need to be overcome for the theory to advance. They note, among other issues, that scholars have not converged on one theoretical framework. The literature includes multiple theoretical frameworks that differ in their interpretations and expressed ends. Similarly, in an assessment of managerial perceptions, Merritt (2019) notes that work on public values does not resolve tensions in the system – the push and pull from regulators, courts, and the public regarding what public organizations should actually be doing.

Public Values, Identification, and Measurement Approaches

A separate but related stream of research aims to identify and classify what qualifies as public values (e.g., Bozeman, 2007; Beck, Jorgensen & Bozeman, 2007), or to identify the mechanisms by which public values are promoted and maintained in the public sector (see Nabatchi, 2018, for a careful distinction between private and public values). Studies in this tradition aim to discover the preferences of public employees or citizens, or more broadly, preferences of an organization or society (Bozeman, 2007; Nabatachi, 2018). Jorgensen's and Bozeman's (2007) inventory of public values derived from political science and public administration literature is an example of this stream of research.

In Public Values and Public Interest (2007), Bozeman distinguishes public values at the societal level from public values at the individual level. Specifically, in societies one can discern patterns of consensus about what everyone should get, what they owe back to society, and how government should work, whereas individuals have their own values in relation to such matters, and the patterns of consensus consist of aggregations of those individuals who agree with each other about such matters:

“A society's ‘public values’ are those providing normative consensus about (a) the rights, benefits, and prerogatives to which citizens should (and should not) be entitled; (b) the obligations of citizens to society, the state, and one another; and (c) the principles on which governments and policies should be based.” (p. 13)

An individual's public values are “the content-specific preferences of individuals concerning, on the one hand, the rights, obligations, and benefits to which citizens are entitled and, on the other hand, the obligations expected of citizens and their designated representatives,” (pp. 13–14)

Public administration scholars who examine public values take a variety of approaches. One approach is to posit public values. Alternatively, one can conduct public opinion polls, survey public managers, or locate public values statements in government agencies' strategic planning documents and mission statements and sometimes in their budget justification documents. Another approach (Jørgensen and Bozeman, 2007) involves developing an inventory of public values from public administration and political science literature. When Jørgensen and Bozeman undertook to develop such an inventory, the list of public values became complex, multileveled, and sometimes mutually conflicting. The inventory includes seven major “value constellations” (Jørgensen and Bozeman, 2007) or “value categories” (Bozeman, 2007, pp. 140–141), each containing a set of values.

The complex results of the inventory should come as no surprise. As many authors have pointed out many times, the values that organizations pursue are diverse, multiple, and conflicting, and the values that government organizations pursue are usually more so. Bozeman (2007, p. 143) contends that lack of complete consensus about public values should not prevent progress in analyzing public interest considerations. He proposes a public value mapping model that includes criteria for use in analyzing public values and public value failure.

Public Values: Advancing the Research and Filling the Voids

Scholars consider Moore's normative approach to creating public value by way of the strategic triangle a significant contribution to public management theory and practice (e.g., Bryson, Crosby, and Bloomberg, 2015; cf. Dahl and Soss, 2014). Yet, it has not garnered much empirical support for its descriptive accuracy or practical efficacy (Bryson, Crosby, and Bloomberg, 2015; Hartley et al., 2016). Also, the limited empirical research on public values tends to focus on managers' conceptions of public values rather than on the views of citizens (e.g., Van der Wal, De Graaf, and Lasthuizen, 2008; Witesman and Walters, 2014). Bozeman (2018) provides an exception. He elicits citizens' views on what does and does not count as public values. Using a list of 14 candidate values and the definition of public values cited previously, Bozeman reports responses that indicate a high level (above 90%) of consensus among citizens regarding what constitutes public values, including freedom of speech; liberty; civil rights; equal pay; freedom of religion; and safety and security. Additionally, a majority (between 62% and 86%) agree that public values include the protection of minority interests, access to health care, economic opportunity, and rights of privacy.

Fukumoto and Bozeman (2019) consider what is missing in the research and acknowledge and note an “identification problem.” In other words, we still do not know what public values are when we see them (p. 638). They contend that part of the problem is the complex nature of values themselves. They advocate advancing public values research by assuming reasonable definitions to examine larger questions. E.g., how do managers and politicians interact to create value? Fukumoto and Bozeman (2019) also encourage a focus on historical perspectives to advance research, similar to that of Moynihan (2009). Moynihan addresses the importance of a historical approach, but primarily to study administrative values, with laws as the primary focus of inquiry.1 Another identification problem concerns the source of public values. Should public values be distilled from the Constitution or other official documents and records (Rosenbloom, 2014), from core values statements (Waerras, 2014), from surveys (Whitesman and Walters, 2015), or from deliberative processes (Nabatchi, 2012)?

In perhaps the most comprehensive treatment of what's missing in public value research, Bryson, Sancino, Benington, and Sorensen (2017) suggest adaptations of Moore's strategic triangle to a contemporary policy environment, where multiple actors confront complex or “wicked” problems (Rittel and Webber, 1973). More specifically, Bryson and his colleagues argue that public value research must take into account fundamental changes in the way public value is defined, produced, and sustained while maintaining a commitment to strengthening democracy (p. 642). They also suggest a new conceptualization for the triangle. E.g., Moore's model places public management at the center of the triangle, whereas Bryson and colleagues not only suggest other actors may be at the center, but they also conceptualize functions, such as organizing effective actor engagement, at the center. They also suggest the model needs extensions to accommodate multiple, often conflicting organizations, interests, and agendas. Bryson et al. (2017) contend that, “Progress in theory, research and practice will depend in part on the operationalization of the different categories of actors, processes, practices, … spheres of action, … along with the new elements … relating to legitimacy and authority, capabilities, public value, and the public sphere” (p. 648).

Research on ethics and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the private sector may also offer avenues to advance research on public values. The focal idea in CSR is the role that businesses play in contributing beneficially to society. Importantly, not all agree that business should address societal problems. Nobel laureate Milton Friedman (1962), e.g., argued that the pursuit of economic benefits should be the only role for firms in a capitalist system. Still, a number of themes in this literature parallel issues in the public values literature. Examples include conceptions of CSR as a decision process (Jones, 1980) or as a systems model of the link between an organization and its social responsibility (Strand, 1983). Others call for CSR as part of an organization's strategy because it offers a competitive advantage (Porter and Kramer, 2006), contributes to long-term success (Porter and Kramer, 2011; Chandler, 2016), or provides new opportunities (Husted and Allen, 2007). Burke and Logsdon (1996) report evidence of a positive association between CSR and businesses' financial performance. CSR researchers have operationalized constructs such as “social return on investment” that may be adaptable to public value research. CSR researchers also track academic interest in CSR in relation to social and economic events, adopting a historical perspective also called for in public values research (e.g., Agudelo et al., 2019).

The Meaning and Nature of Public Organizations and Public Management

Although the idea of a public domain within society is an ancient one, beliefs about what is appropriately public and what is private, in both personal affairs and social organization, have varied among societies and over time. The word public comes from the Latin for “people,” and Webster's New World Dictionary defines it as pertaining to the people of a community, nation, or state. The word private comes from the Latin word that means to be deprived of public office or set apart from government. In contemporary definitions, the distinction between public and private often involves three major factors (Benn and Gaus, 1983): interests affected (whether benefits or losses are communal or restricted to individuals); access to facilities, resources, or information; and agency (whether a person or organization acts as an individual or for the community as a whole). These dimensions can be independent of one another and even contradictory. E.g., a military base may purportedly operate in the public interest, acting as an agent for the nation, but deny public access to its facilities.

Approaches to Defining Public Organizations and Public Managers. The multiple dimensions along which the concepts of public and private vary make for many ways to define public organizations. E.g., one time-honored approach defines public organizations as those that have a great impact on the public interest (Dewey, 1927). Decisions about whether government should regulate have turned on judgments about the public interest (Mitnick, 1980). In a prominent typology of organizations, Blau and Scott (1962) distinguished between commonweal organizations, which benefit the public in general, and business organizations, which benefit their owners. The public interest, however, has proved notoriously hard to define and measure (Mitnick, 1980). Some definitions directly conflict with others: e.g., defining the public interest as what a philosopher king or benevolent dictator decides versus what the majority of people prefer. Most organizations, including business firms, affect the public interest in some sense. Manufacturers of computers, pharmaceuticals, automobiles, and many other products clearly have influence on the well-being of many nations.

Alternatively, researchers and managers often refer to auspices or ownership – an implicit use of the agency factor mentioned earlier. Public organizations are governmental organizations, and private organizations are nongovernmental, usually business firms. The blurring of the boundaries between the sectors, however, shows that we need further analysis of what this dichotomy means.

Agencies and Enterprises as Points on a Continuum. Observations about the blurring of the sectors are hardly original. Half a century ago, in their analysis of markets and polyarchies, Dahl and Lindblom (1953) described a complex continuum of types of organizations, ranging from enterprises (organizations controlled primarily by markets) to agencies (government-owned organizations). For enterprises, they argued, the pricing system automatically links revenues to products and services sold. This creates stronger incentives for cost reduction in enterprises than in agencies. Agencies, conversely, have more trouble integrating cost reduction into their goals and coordinating spending and revenue-raising decisions, because legislatures assign their tasks and funds separately. Their funding allocations usually depend on past levels, and if they achieve improvements in efficiency, their appropriations are likely to be cut. Agencies also pursue more intangible, diverse objectives, making their efficiency harder to measure. The difficulty in specifying and measuring objectives causes officials to try to control agencies through enforcement of rigid procedures rather than through evaluations of products and services. Agencies also have more problems related to hierarchical control – such as red tape, buck passing, rigidity, and timidity – than do enterprises.

More important than these assertions in Dahl's and Lindblom's comparison of agencies and enterprises is their conception of a continuum of various forms of agencies and enterprises, ranging from the most public of organizations to the most private (see Figure 3.1). Dahl and Lindblom did not explain how their assertions about the different characteristics of agencies and enterprises apply to organizations on different points of the continuum. Implicitly, however, they suggested that agency characteristics apply less and less as one moves away from that.

Ownership and Funding. Wamsley and Zald (1973) pointed out that an organization's place along the public–private continuum depends on at least two major elements: ownership and funding. Organizations can be owned by the government or privately owned. They can receive most of their funding from government sources, such as budget allocations from legislative bodies, or they can receive most of it from private sources, such as donations or sales within economic markets. Putting these two dichotomies together results in the four categories illustrated in Figure 3.2: publicly owned and funded organizations, such as most government agencies; publicly owned but privately funded organizations, such as the US Postal Service and government-owned utilities; privately owned but governmentally funded organizations, such as certain defense firms funded primarily through government contracts; and privately owned and funded organizations, such as supermarket chains and IBM.

| The figure displays the continuum between government ownership and private ownership. Below the line are arrangements colloquially referred to as public, government-owned, or nationalized. Above the line are organizational forms usually referred to as private enterprise or free enterprise. On the line are arrangements popularly considered neither public nor private. | ||||||

| Private nonprofit organizations totally reliant on government contracts and grants (Atomic Energy Commission, Manpower Development Research Corporation) | Private corporations reliant on government contracts for most revenues (some defense contractors, such as General Dynamics, Grumman) | Heavily regulated private firms (heavily regulated private utilities) | Private corporations with significant funding from government contracts but with the majority of revenues from private sources | Private corporations subject to general government regulations such as affirmative action, Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulations | Private enterprise | |

| Government ownership of part of a private corporation | ||||||

| Government agency | State-owned enterprise or public corporation (Postal Service, TVA, Port Authority of NY) | Government-sponsored enterprise, established by government but with shares traded on the stock market (Federal National Mortgage Association) | Government program or agency operated largely through purchases from private vendors or producers (Medicare, public housing) | |||

Source: Adapted and revised from Dahl and Lindblom, 1953.

FIGURE 3.1 AGENCIES, ENTERPRISES, AND HYBRID ORGANIZATIONS

| Public Ownership | Private Ownership | |

Public Funding (taxes, government contracts) |

Department of Defense Social Security Administration Police departments |

Defense contractors Rand Corporation Manpower Development Research Corporation Oak Ridge National Laboratories |

Private Funding (sales, private donations) |

U.S. Postal Service Government-owned utilities Federal Home Loan Bank Board |

Apple Corporationaa Microsoft General Electric Grocery store chains YMCA |

a These large corporations have large government contracts and sales, but attain most of their revenues from private sales and have relative autonomy to withdraw from dealing with government.

Source: Adapted and revised from Wamsley and Zald, 1973.

FIGURE 3.2 PUBLIC AND PRIVATE OWNERSHIP AND FUNDING

This scheme does have limitations; it makes no mention of regulation, e.g. Many corporations, such as IBM, receive funding from government contracts but operate so autonomously that they clearly belong in the private category. Nevertheless, the approach provides a fairly clear way of identifying core categories of public and private organizations.

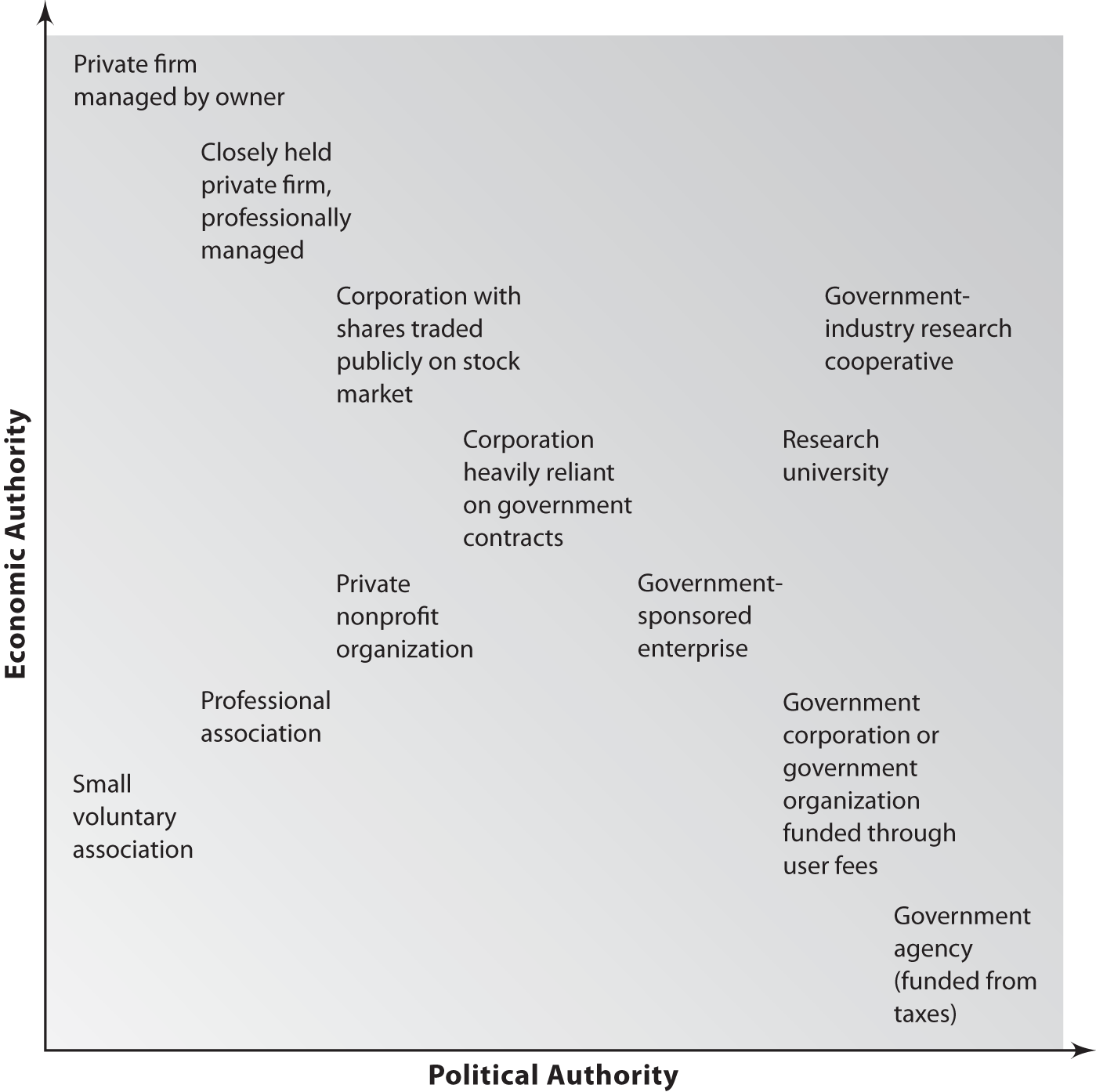

Economic Authority, Public Authority, and “Publicness.” Bozeman (1987) drew on a number of the preceding points to conceive the complex variations across the public–private continuum. All organizations have some degree of political influence and are subject to some level of external governmental control. Hence, they all have some level of “publicness,” although that level varies widely. Like Wamsley and Zald, Bozeman used two subdimensions – political authority and economic authority – but treated them as continua rather than dichotomies. Economic authority increases as owners and managers gain more control over the use of their organization's revenues and assets, and it decreases as external government authorities gain more control over their finances.

Political authority is granted by other elements of the political system, such as the citizenry or governmental institutions. It enables the organization to act on behalf of those elements and to make binding decisions for them. Private firms have relatively little of this authority. They operate on their own behalf and only for as long as they support themselves through voluntary exchanges with citizens. Government agencies have high levels of authority to act for the community or country, and citizens are compelled to support their activities through taxes and other requirements.

The publicness of an organization depends on the combination of these two dimensions. Figure 3.3 illustrates Bozeman's depiction of possible combinations. As in previous approaches, the owner-managed private firm occupies one extreme (high on economic authority, low on political authority), and the traditional government bureau occupies the other (low on economic authority, high on political authority). A more complex array of organizations represents various combinations of the two dimensions. Bozeman and his colleagues have used this approach to design research on public, private, and intermediate forms of research and development laboratories and other organizations. Later chapters describe the important differences they found between the public and private categories, with the intermediate forms falling in between (Bozeman and Loveless, 1987; Coursey and Rainey, 1990; Crow and Bozeman, 1987; Emmert and Crow, 1988). Also employing a concept of publicness, Antonsen and Jorgensen (1997) compared sets of Danish government agencies high on criteria of publicness, such as the number of reasons their executives gave for being part of the public sector (as opposed to being in the public sector as a matter of tradition or for economies of scale). The agencies scoring high on publicness showed a number of differences from those low on this measure, such as higher levels of goal complexity and of external oversight.

FIGURE 3.3 “PUBLICNESS”: POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC AUTHORITY

Even these more complex efforts to clarify the public–private dimension do not capture its full complexity. Government and political processes influence organizations in many ways: through laws, regulations, grants, contracts, charters, franchises, direct ownership (with many variations in oversight), and numerous other ways. Private market influences also involve many variations. Perry and Rainey (1988) suggested that future research could continue to compare organizations in different categories, such as those in Table 3.3.

Although this topic needs further refinement, these analyses of the public–private dimension of organizations clarify important points. Simply stating that the public and private sectors are not distinct does little good. The challenge involves conceiving and analyzing the differences, variations, and similarities. In starting to do so, we can think with reasonable clarity about a distinction between public and private organizations, although we must always realize the complications. We can think of assertions about public organizations that apply primarily to organizations owned and funded by government, such as typical government agencies. At least by definition, they differ from privately owned firms, which get most of their resources from private sources and are not subject to extensive government regulations. We can then seek evidence comparing these two groups, and in fact such research often shows differences, although we need much more evidence. The population of hybrid and third-sector organizations raises complications about whether and how differences between these core public and private categories apply to those hybrid categories. Yet we have increasing evidence that organizations in this intermediate group – even within the same function or industry – differ in important ways on the basis of how public or private they are.

TABLE 3.3 TYPOLOGY OF ORGANIZATIONS CREATED BY CROSS-CLASSIFYING OWNERSHIP, FUNDING, AND MODEL OF SOCIAL CONTROL

Source: Adapted and revised from Perry and Rainey, 1988

| Ownership | Funding | Mode of Social Control | Representative Study | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bureau | Public | Public | Polyarchy | Meier and Bohte (2007) | Bureau of Labor Statistics |

| Government corporation | Public | Private | Polyarchy | Walsh (1978) | Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation |

| Government-sponsored enterprise | Private | Public | Polyarchy | Musolf and Seidman (1980) | Corporation for Public Broadcasting |

| Regulated enterprise | Private | Private | Polyarchy | Mitnick (1980) | Private electric utilities |

| Government enterprise | Public | Public | Market | Barzelay (1992) | Government printing office that must sell services to government agencies |

| State-owned enterprise | Public | Private | Market | Aharoni (1986) | Airbus |

| Government contractor | Private | Public | Market | Bozeman (1987) | Grumman |

| Private enterprise | Private | Private | Market | Williamson (1975) | IBM |

Problems and Approaches in Public–Private Comparisons

Defining a distinction between public and private organizations does not prove that important differences between them actually exist. We need to consider the alleged differences and the evidence for or against them. First, however, we must consider challenges in research on public–private comparisons.

The discussion of the generic approach to organizational analysis and contingency theory introduced some of these challenges. Many factors, such as size, task or function, and industry characteristics, can influence an organization more than its status as a governmental entity. Research needs to show that these alternative factors do not confuse analysis of differences between public organizations and other types. Obviously, e.g., if you compare large public agencies to small private firms and find the agencies more bureaucratic, size may be the real explanation. Also, one would not compare a set of public hospitals to private utilities as a way of assessing the nature of public organizations. Ideally, an analysis of the public–private dimension requires a convincing sample, with a good model that accounts for other variables besides the public–private dimension. Ideally, studies would also have huge, well-designed samples of organizations and employees, representing many functions and controlling for many variables. Such studies require a lot of resources and have been virtually nonexistent, with the exception of the example of the National Organizations Study (which found differences among public, nonprofit, and private organizations, as described in Chapter Eight; see Kalleberg, Knoke, and Marsden, 2001; Kalleberg, Knoke, Marsden, and Spaeth, 1996). Instead, researchers and practitioners have adopted a variety of less comprehensive approaches.

Some writers theorized on the basis of assumptions, previous literature, and their own experiences (Dahl and Lindblom, 1953; Downs, 1967; Gawthorp, 1969; Mainzer, 1973; Wilson, 1989). Other researchers have measured or observed public bureaucracies and draw conclusions about their differences from private organizations. Some concentrated on one agency (Warwick, 1975), some on many agencies (Meyer, 1979). Although valuable, these studies examined no private organizations directly.