TWO

Crossing Boundaries to Investigate Problems in the Field

An Approach to Useful Research

FOR MOST SCHOLARS in organizational behavior, the importance of advancing theory is obvious. In a field that arose in response to management challenges (Miner, 2002), one might argue that research advancing practice should be highly valued as well. Indeed, the need for strategies to manage the challenges faced by the organizations that inspire and fund our work creates an obvious imperative for research that helps those who manage and work in them.

We are told that the norms and demands of academic careers limit our ability to be useful (e.g., Fox, 2003). As the scholars in this book illustrate, however, the hurdles are far from insurmountable. Perhaps the dichotomy between theory and practice need not be so pronounced. Indeed, many of us draw inspiration from Kurt Lewin (1945, p. 129), who argued, over a half century ago, “Nothing is as practical as a good theory.” In this well-known statement, Lewin was not claiming that theory, by its very existence, is practical and should be respected as such, but rather that a good theory is one that can demonstrate its claim. As Lewin’s student Chris Argyris (e.g., 1980, 1982, 1993) has argued tirelessly, this is a tall order, but one that management researchers must embrace if we are to make a difference in the world. Though few journals appear to seek out or publish work with a practical component, the tradition of action research has remained vital and inspiring over the intervening decades (e.g., Argyris, Putnam, & Smith, 1988; Clark, 1980; Fox, 2003; Schein, 1987; Schwarz, 1994).

What drew me to the field of organizational behavior twenty years ago was exactly this opportunity—to engage in research and teaching aimed at understanding and informing practice. Yet those just starting research careers might be well advised not to read on. The approach I describe in this chapter—starting with problems, going out into the field, and reaching across boundaries of several kinds—is almost certain to slow you down and may even harm your career. (Of course, I hope not, and I don’t believe it to be true. But many do, and so I offer this reluctant caveat as an invitation to help challenge it.)

This chapter presents experiential reflections rather than systematic analyses. I did not conduct a literature search to identify and analyze useful studies so as to determine what they have in common, but instead reflected on my own research activities over the past two decades to consider what factors have been most instrumental in tying me to practice. I did not need to be convinced to pursue practical knowledge. This aim was embedded in my long-standing sense of purpose. Coming from a family of inventors and engineers, I began the study of organizational behavior in the early 1990s with a deep bias toward the pursuit of the practical. A decade earlier, in my first job after college, I worked as an engineer for Buckminster Fuller, designing and building geodesic domes for uses ranging from food production to emergency shelter. Fuller—a college dropout from the Harvard class of 1917 and at the time an internationally known inventor, architect, and author—was the perfect mentor to reinforce my bias against further academic endeavors. Drawing from these family and early career influences, I had been certain that making a difference in the world did not involve time out for graduate school. Furthermore, at that time, I was not yet aware of the field of organizational behavior.

What happened to change my course from applied engineering to organizational research? To begin, while working with Fuller, I led the occasional team in the construction of full-scale geodesic prototypes, sparking an initial, but still largely dormant, interest in organizational dynamics that affect collaborative work. After Fuller’s death in 1983, I wrote a book about his mathematical concepts (Edmondson, 1987) but remained mute on his efforts to inspire and engage people in work that made a difference in the world—ideas well captured by others (e.g., Baldwin, 1996; Kenner, 1973). It was not until a few years later, working for a small consulting firm that helped managers implement change programs in companies, that I became aware of the need for better knowledge about the design and management of organizations. In that job, I spent many hours interviewing and observing in large companies as varied as General Motors and Apple, obtaining the beginnings of an education in organizational behavior. I decided to apply to graduate school at the point when I realized that my ignorance in psychology, management, and business was limiting my usefulness in these settings.

As a doctoral student, however, I soon found that usefulness was not at the top of the list of criteria with which scholars evaluated research in organizational behavior. Discovering the predecessor to this book, Doing Research That Is Useful for Theory and Practice (1985), thus had been profoundly reassuring. The essays and dialogue among so many of the field’s leading researchers—Chris Argyris, Paul Goodman, Richard Hackman, Ed Lawler, Dick Walton—made it clear to me that an aspiration to develop practical knowledge in organization studies was consistent with the purpose of the field.

Reflecting on how this quest has played out in the past two decades in my own work, I identified three attributes of my approach to conducting research that may increase the chances of the research being useful: starting with an important problem, getting into the field (early and often), and not being afraid to collaborate across disciplinary and organizational boundaries. Although of dubious merit as a theory of relevance, these elements are likely to increase the chances of stumbling into useful knowledge and almost certainly make the research journey more interesting.

Three Elements of Useful Research

Start with Problems

Problems provide a natural connection with practice. Studying a compelling problem, researchers are motivated to care about action. Problems matter! They matter to actors in the field coping with them, of course, and those reading one’s work are likely to find them interesting as well (Fox, 2003). As compelling as publishing articles for scholarly colleagues may be, research that might help solve a problem in the world is usually that much more so.

The problem with problems is, of course, their apparently low status as “applied” research (Fox, 2003; Greenwood & Levin, 1998). And, problem-driven research brings additional risks to scholars. First, the work might turn out to be mundane if it merely addresses a problem that seems important to practitioners but uninspiring to other scholars. Second, problem-driven research risks rediscovering the obvious or generating pragmatic but situation-specific recommendations. Theory-driven research, in comparison, is awarded higher status and is believed to be more general and enduring (Fox, 2003). I nonetheless argue that problems open doors to new ideas and new theory. Starting with an important problem does not mean one must solve it single-handedly but rather that one can use it as a lens with which to investigate an organizational phenomenon that has importance for practices as well as for theory. Starting with a problem does, I believe, call for at least interest in solutions, as well as for empathy for those who face the problem.

One obvious reason that research motivated by problems might increase its usefulness is that efforts to understand a problem are likely to trigger ideas about how to solve it. Occasionally, solutions to problems can be investigated, tested, or refined, whether in the same or in subsequent research projects (Clark, 1980). More subtly, problems may facilitate the production of useful research because real problems in organizations are complex and multifaceted, provoking consideration of issues beyond those that motivated the study in the first place. In contrast to theory-driven research, which often remains tightly focused—adhering to a specific research framework and design—problem-driven research may sometimes follow the trail of problems where it leads. Lateral thinking about issues related to the initial problem then may trigger ideas for practice as well as new ideas for theory. Perhaps most important, developing knowledge about a problem builds the depth of understanding that makes the solutions researchers or their organizational partners might design more likely to work.

A study of errors

To illustrate, medication error in hospitals is an example of a real world problem. Motivated by research interests in both organizational learning and workplace safety, in the early 1990s I joined a team of nurses and physicians in an in-depth study of medication errors in hospitals. The team was organized to collect data to measure error rates in a dozen or so hospital units (work groups that provide patient care) in two hospitals with attention to potential organizational causes of error. I thus joined the team with a narrow research question: Did better teams make fewer errors? My design would predict the team-level error rate (being assessed by data on medication errors to be collected by clinicians over a six-month period) with data on team design, team process, and leader behavior, collected during the first month of the study. I used a modified version of Richard Hackman’s team diagnostic survey to measure team properties (Wageman, Hackman, & Lehman, 2005). From a practice perspective, if my main hypothesis was supported, efforts to build stronger unit-based teams might help reduce errors.

The reality of drug errors was more complex than my initial design had considered. Reflecting a risk for problem-driven research in general, the process of digging into the problem of drug errors uncovered a new, related problem. This came to light when my analysis of the painstakingly collected quantitative data produced findings that appeared to be the exact opposite of what I had predicted: Well-led teams with good relationships among members were apparently making more mistakes related to medications, not fewer. There was a significant correlation between teamwork and error rates in what I initially considered “the wrong direction.” This was a surprise—and of course, a puzzle. Did better-led teams really make more mistakes? With what I had learned of the phenomenon already at that point—the many handoffs across caregivers, the need for communication, coordination, help-seeking, and double-checking to achieve safe, error-free care—I did not think it made sense that good teamwork would increase the chance of errors. The opportunity to get into the field, described in the section titled “Strategies for Building Understanding in the Field,” was essential to getting to the bottom of this unexpected result.

Other problem-inspired studies

Although medication errors present a particularly tangible example, organizational problems come in many forms and can motivate a variety of research projects. Other examples from my own work include action research with a senior management team in a midsized U.S. manufacturing company facing declining revenues and profits after a half century of growth (Edmondson & Smith, 2006), a study of the difficulties of changing surgical team behaviors to accommodate a new technology (Edmondson, Bohmer, & Pisano, 2001a), an investigation of inconsistent use of best practices across neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) in North American hospitals (Tucker, Nembhard, & Edmondson, 2007), and a study of speaking up failures in a multinational company (Detert & Edmondson, 2010).

All of these studies were motivated by problems and management challenges that were important to people working in the involved organizations. At the same time, I entered each of them hoping to be able to contribute knowledge to organizational learning research as well. Further, none of these studies produced the findings or theoretical contributions I expected or hoped for at the outset. Although I believe the actual contributions were more interesting than those planned, I am not an objective judge. In any case, the time spent studying the issues that started the projects invariably led to new questions, new insights, and some unexpected contributions to the literature.

For example, at the beginning of our study of a new surgical technology, my colleague, Gary Pisano, wanted to study learning curves in a service setting. As an economist with expertise in manufacturing—particularly in the process innovations involved in the manufacture of complex pharmaceuticals (see Pisano, 1996)—Pisano saw cardiac surgery as a novel setting for investigating learning curves. With a well-developed network in health care businesses, he soon identified a device maker launching an innovative technology for minimally invasive surgery and requested its help collecting data on surgical time for consecutive operations from several of the adopting hospitals. Both the company and the hospitals participated willingly, hoping to learn from the research.

Unexpectedly, in his early conversations, salespeople in close contact with the clinicians repeatedly told Pisano that success with the new technology was all about “the team” and its “teamwork.” These comments made Pisano understandably nervous; as an economist, teamwork was not something he had been prepared to consider, let alone measure. But, my office was next door to his, and soon he had me as a new collaborator. (Richard Bohmer, a physician, also joined the team, a crucial addition, as noted in the section titled “Disciplinary boundaries.”) Together, we shifted gears to include extensive interviews with all members of the operating room teams and others close to the technology implementation efforts in 16 hospitals. Having been led by the sales representatives to study the “problem” of needing a new kind of teamwork to succeed with minimally invasive surgery, we had a new focus to our collaborative research. Indeed, fewer than half of the 16 adopting cardiac surgery departments we studied successfully implemented the technology (that is, they continued to offer the procedure after an initial learning period). Others abandoned the effort, leaving future patients without the option of a less invasive operation and a quicker recovery. As our qualitative data revealed, operating room teams had to figure out new ways of working together to accommodate the new technology, and this proved far from easy.

Similarly, the problem of a weak strategy and deteriorating business results that initiated our action research with the senior management team in the manufacturing company also unveiled a new, different problem for us to study: how to manage emotion-laden interpersonal conflicts in a decision-making group (Edmondson & Smith, 2006). This new problem was of great interest to us as scholars, and the challenge it presented captured the attention of our executive colleagues as well.

Back in the hospital context, when my colleagues and I set out to study best practice implementation teams in the NICU, the perceived problem according to the two physicians who first contacted me was to speed up team learning. But, along the way, a new problem emerged: the state of medical knowledge (the “evidence”) supporting the practices being implemented by the unit-based teams varied widely. With less research evidence of medical efficacy, teams had more difficulty implementing the required changes in their organizations (Tucker, Nembhard, & Edmondson, 2007).

Summary

In each of these projects, problems were helpful for focusing and motivating the research activities. Problems spawned research questions, generated insights and solutions, and most of all, facilitated access to field sites. Without problems, our field-based collaborators would have been far less likely to welcome us into their world, offering us access to data. And, in each case, the initial problem did not tell the whole story of the phenomenon. Field-based research allowed the problems and plots to shift and to thicken.

Go Out into the Field

Unless you have an unusual office location, sitting at your desk is unlikely to be the most conducive situation for gaining insight into the kinds of organizational phenomena previously described. Although one can learn about an industry or company from written materials, fuller understanding and new ideas are more likely when meeting and observing people who work in that setting. Deciding to pursue field-based research also has its risks. One can negotiate access to a site only to have it fall through, or have it not offer the kind of data needed for answering a research question. Moreover, understanding a situation well requires multiple observations, and some interviews or visits do not yield anything useful. Further, as noted in the prior section titled “Start with Problems,” the research question one asks may evolve as understanding of the setting deepens, posing challenges for consistency. In short, the research process can be inefficient, fraught with logistical hurdles and unexpected events (see Edmondson & McManus, 2007). Nonetheless, getting into the field is essential for building understanding of a context and of the variables that matter therein.

Strategies for building understanding in the field

I have engaged in two basic types of field research. The first involves open-ended exploration of a phenomenon or a research possibility without extensive structure, careful sampling, or highly structured interview protocols. In this type of research, one spends time in the field to get up to speed in understanding a setting—learning relevant terminology and discovering issues that matter. The second type is more focused and involves more systematic techniques of collecting data to develop, support, and sometimes test a theoretical proposition. Generally, the first kind of research experience precedes the second, although exploratory forays do not lead inexorably to subsequent, more structured phases.

For example, the time I spent in the field to investigate medication errors occurred in two distinct phases. In the first phase, I participated in biweekly research meetings at one of the hospitals for most of a year, reviewing many of the detected errors and conducting interviews to gain insight into what had happened leading up to, during, and after many of the errors. These experiences helped me to develop survey items that were meaningful in the hospital context, as well as to build confidence in my understanding of health care delivery and its many challenges, including its highly specialized terms and jargon. In the second phase of fieldwork, I asked a research assistant (Andy Molinsky, now a professor of organizational behavior at Brandeis University) to observe and interview members of the hospital units to better understand any organizational differences they might have. At that point, I was hoping to shed light on the unexpected correlation between error rates and teamwork, and it was important that the research assistant remain blind to the error data, the survey data, and to the new idea I had about what might explain the significant correlation between them. From Molinsky’s perspective, the data collection was highly unstructured, by design. From my perspective, I knew the relationship I wanted to explain, and I hoped that he would find evidence of unit-based differences in error-reporting behavior.

Why might stronger teams have higher error rates? As I thought further about this question, it occurred to me that well-led teams, compared to teams with poor relationships among colleagues or with punitive leaders, might have a climate of openness that made it easier to report and discuss error. The good teams, I reasoned, do not make more mistakes, they report more. When I suggested this to the study’s principal investigators, they were skeptical. This interpretation suggested that we might not be finding the definitive error rate—a primary goal of the larger study—and that errors might be systematically underreported in some units due to retaliatory interpersonal climates. The physicians’ skepticism led me to conduct further analyses and to collect additional data to test this new proposition.

I ran additional analyses with the error and survey data and waited while Molinsky—still blind to both sets of measures and unaware of my new hypothesis—conducted open-ended interviews and observations in the hospital units over several weeks to gain insight into these small workplaces (see Edmondson, 1996, for more detail). These new data strongly suggested that there were palpable differences in interpersonal climate across units. It was particularly noteworthy that people’s reported levels of willingness to speak up about errors appeared to vary widely. Furthermore, these differences—the independent ratings of unit openness—were highly correlated with the detected error rates. This observation, gleaned from the field interviews, gave rise to a new stream of inquiry on psychological safety (e.g., Edmondson, 1999, 2002, 2003b).

Working in this new stream, my next field study showed that psychological safety varies significantly across groups and predicts team learning and performance (Edmondson, 1999). This project also involved two distinct phases of qualitative data collection in the field, one more open ended and one more focused. The earlier phase developed understanding of the context (a midsized manufacturing company serving corporate customers) and investigated team processes for evidence of the construct of team psychological safety and to inform survey construction. The later phase, following survey administration and analysis, was a targeted examination of the phenomenon of team learning, comparing high- and low-learning teams. This intensive field-based research greatly enhanced the study by illuminating the phenomenon of team learning and making relationships between constructs far more compelling and convincing than they would have been with the survey data alone (see Edmondson, 1999; Edmondson & McManus, 2007).

Shifting questions, insights, and implications

Although very few studies produce statistically significant results that are the opposite of those predicted, field-based research rarely fails to yield some surprises along the way. As already noted, all of the problem-driven research projects previously discussed experienced important shifts in emphasis as a result of the time spent in the field. For example, our action research on the senior management team revealed a team stuck in persistent conflicts. These executives seemed unable to resolve deeply held conflicting views about firm strategy. The team debated crucial decisions about product position and price for months, making little progress, as we observed and recorded their conversations. Spending time in the field with the team was essential for understanding why it was making so little progress. Diana Smith and I observed and recorded full-day meetings and conducted interviews with individuals. Our analysis of the transcript data focused on the conversations featuring disagreements that continued over time, from meeting to meeting.

Reading the literature on team conflict while analyzing these data, Smith and I took note of prominent theories that task conflict promotes, while relationship conflict harms, team effectiveness (e.g., Amason, 1996; Jehn, 1997). Although both the claim of distinct conflict constructs and the theoretical argument about differential effects were logical and intuitively appealing, our data suggested a different perspective. Analyzing transcript after transcript, supplemented by private interviews with team members, we began to notice that certain types of task conflict in this team naturally triggered relationship conflict. Specifically, when team conflicts encompassed opposing value systems—deeply held opinions or organizational values—relationship conflicts were virtually inevitable. We argued that this fusion occurred because in the process of arguing one or another side of a debate, participants could not help making negative interpersonal attributions about those arguing a view that opposed their own. These attributions—whether essentially about others’ incompetence or stubbornness—were readily revealed to us in interviews.

We further suspected that the executives’ intention to remain on the business topics and avoid interpersonal issues made it difficult for them to make progress in their strategic decision-making task (Edmondson & Smith, 2006). The relationship tensions under the surface were off limits—“undiscussables” (Argyris, 1980)—and the mutual pretense that only business-based discussion was occurring added to, rather than lessened, the team’s challenge. We thus used the data—on both the problem and on the interventions and their effects—to propose (and test in several settings) a new approach to managing relationship conflict in management teams.

When Jim Detert and I started the study of speaking-up failures previously mentioned, we wondered what made psychological safety for voice low in the knowledge-intensive company we called HiCo. We were not thinking about or looking for implicit theories of voice until our analysis of reams of interview data, which encompassed over 170 specific episodes of speaking up (or not speaking up) at work, suggested some common (and surprising) features of how people thought about speaking up. In this way, we identified a set of implicit theories about when and where speaking up is unsafe or inappropriate in corporate hierarchies. These implicit theories function, we argued, as cognitive programs leading people to choose silence over voice, even with content that is not inherently threatening. That is, even with good ideas rather than bad news, people may frequently hold back on voice, much to the detriment of the organization, and in the long run, to themselves.

In this study, it was deeper investigation of the intrapersonal sense making that underlies specific voice decisions—in the context of real organizational situations—that led us to revisit the literature on implicit theories and then to formulate what we hope is a novel contribution to the voice literature. What we found especially satisfying about the implicit theories perspective was its potential to develop actionable communication strategies for managers who wish to better engage employee voice (Detert & Edmondson, 2011).

New variables emerge

Extensive fieldwork was also crucial to developing insight into the nature of the behavioral changes required to successfully implement the new cardiac surgical technology. For instance, many of the usual variables associated with differences in innovation success, such as top management support, level of resources, or status of the project leader, provided no explanatory value in this setting. As we learned in the field, cardiac surgeons had enormous status and generated considerable resources for hospitals and so were less vulnerable to the need for support from senior management. However, many underestimated the need for behavioral changes in the operating room, by themselves and by other members of the team. The surgeons who framed the implementation process as a team-learning journey—fewer than half of those studied—oversaw successful implementations (Edmondson, 2003b).

Similarly, to understand the problem faced by the NICU improvement teams and the setting in which they worked, my colleagues and I visited four hospitals to do extensive interviews. We used these visits to develop brief case studies on ten improvement projects occurring in the four hospitals, projects that ranged in focus from hand hygiene to intergroup relations between the maternity/delivery and NICU units. The case studies, in turn, informed the development of a survey instrument and helped us to understand what made quality improvement challenging in hospitals. But a crucial variable that differentiated these improvement projects, which we had not been aware of when we started the research, was the level of evidence supporting a given practice being implemented. The fieldwork allowed us to add this variable to our quantitative data collection efforts that followed.

Summary

Research questions and problems are likely to shift during field research, building greater understanding and pointing to additional theoretical and practical possibilities. At the same time, field researchers must be prepared to accept that every foray into the field will not lead to an article in a top scholarly journal. Field research is replete with false starts and dead ends, as noted earlier. Yet, field visits—even those that do not end up as full-blown research sites—can provide data for illustrating insights and mechanisms in papers or talks, or for developing case studies for teaching. The opportunity to gain firsthand knowledge in a field site is thus valuable for personal learning and for improving the ability to communicate ideas and findings to others. Field-based case studies serve as data points that build understanding and generate ideas. Moreover, prior field experience triggers a virtuous cycle of access to future field experience, building credibility for future, more promising research sites.

Collaborate across Knowledge Boundaries

In most field research sites, it takes time to understand both the organization and the industry. Collaborators who bring different perspectives and expertise can accelerate the learning needed to get up to speed and offer novel insights. For me to understand drug errors in hospitals, for example, would have been extremely difficult without working closely with the physicians and nurses in the larger research project. Similarly, working with scholars in other disciplines allows a fuller picture of the phenomenon under study to take shape, compared to working alone or working with similarly trained colleagues. This fuller picture, I believe, increases the chances of producing actionable knowledge. In our cardiac surgery study, for example, my two colleagues and I looked at what was happening in these teams from very different perspectives, which we were able to integrate to ultimately develop papers for both researchers and practitioners. In sum, there are two kinds of knowledge boundaries worth crossing in problem-focused, field-based research: organizational and disciplinary. Some collaborations cross both, but one is likely to be more salient than the other in a given project.

Organizational boundaries

Clearly, working closely with practitioners—managers, clinicians, engineers, other professionals—encourages attention to practical issues. For example, clinician collaborators in the drug error study brought disciplinary knowledge that I lacked, but as actors in the organizations under study, they brought practitioner perspectives that were especially valuable to my understanding the interdependence of how drugs are delivered in these complex organizations. This insight suggested that interpersonal climate might be an important variable in predicting error rates. These findings had clear implications for practice. They helped to generate productive discussion of the problem of fear in medicine, both behind closed doors in physician residency programs and publicly. In particular, they began to introduce into the larger health care dialogue consideration of how reluctance to speak up about errors or to ask for help was making patients less safe than they would otherwise be (e.g., Edmondson, 2004; Leape, 1999, 2007; Shortell & Singer, 2008). Since that time, many hospitals have pursued blameless reporting policies to increase the chances of detecting, correcting, and preventing future error (see Edmondson, Roberto, & Tucker, 2002). The study also had implications for theory, in that the discovery of the role of psychological safety influenced my own and others’ subsequent theory and research on learning and teams (Baer & Frese, 2003; Edmondson, 1999, 2002, 2003b; Levin & Cross, 2004). Additionally, the relationships with health care insiders in this work led to additional research opportunities in other hospitals (e.g., Tucker, Nembhard, & Edmondson, 2007; Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006).

Although in a less technically complex setting, my study of 51 teams in a low-tech manufacturing company (“ODI”) would not have been possible without the active participation of a manager I called Dave Kane (Edmondson, 1996). Kane’s request for help assessing the teams at ODI allowed me to gather data to test a theoretical model of team learning (Edmondson, 1999). Kane and his colleagues’ engagement in the research as it unfolded allowed me to build understanding of the teams’ work, to obtain superb response rates, and to help push my thinking about psychological safety and team learning.

More recently, I have investigated organizational learning failures through case study research in a variety of settings. Although few of these projects led to scholarly papers, they fostered the development of practical knowledge on how to lead change in highly uncertain contexts (Edmondson, Roberto, & Tucker, 2002); how to anticipate and respond to ambiguous threats (Edmondson et al., 2005); and how to build psychological safety in a large organization (Edmondson & Hajim, 2003), communicated in book chapters, managerial articles, teaching notes, and the occasional research paper. I have found such case studies, focused initially on pedagogical aims, to be helpful in generating future research ideas (e.g., Edmondson et al., 2005; Hackman & Edmondson, 2007). In most of these studies, organization members have been crucial partners. Their involvement helped to focus each investigation, bringing together well selected interviewees, and to identify managerially relevant decisions and tensions, which was especially important for furthering knowledge about practice in reasonably complex organizational settings.

Disciplinary boundaries

The other kind of collaboration involves crossing boundaries between academic disciplines. Colleagues in other fields may have experience in an industry or perspectives on a phenomenon that complement those from behavioral and organizational sciences. In the study of cardiac surgery teams, Pisano, an economist, brought expertise in operations and learning curve analysis and Bohmer, a physician, demystified the surgical task while I helped them to better understand the research on teams. The journey was both engaging and challenging; we had many discussions in which taken-for-granted assumptions within our different disciplines—especially economics and organizational behavior—clashed. For example, economics had little history with the kinds of qualitative data I proposed to use to assess differences across sites. Such differences led to interesting discussions in both scholarly (Pisano, Bohmer, & Edmondson, 2001; Edmondson, Bohmer, & Pisano, 2001a) and managerial (Edmondson, Bohmer, & Pisano, 2001b) articles. Our first publication, describing the heterogeneity of learning curves in the service context, would not have been possible without Bohmer’s help conversing with surgeons to identify the right control variables (Pisano, Bohmer, & Edmondson, 2001). Our final paper described what we had discovered about fast-learning teams to a managerial audience (Edmondson, Bohmer, & Pisano, 2001b).

Similarly, in our later study of NICUs, collaborating with scholars with deep expertise in operations management (Anita Tucker) and health care management (Ingrid Nembhard) allowed the development of a survey instrument that included significant predictors of implementation success taken from our three different respective literatures.

My collaboration with Diana Smith crossed another type of boundary between researchers: action research in a consulting setting versus normal science research in an academic setting. Although both trained in organizational behavior, Diana and I differ in our skills and methods. She is an extraordinarily skillful action researcher who intervenes in management contexts to improve practice and build new knowledge (Smith, 2008), while I have largely developed and tested conceptual models. Working together helped us both push our thinking about the phenomenon of conflict in management teams—with mutual intellectual benefits and considerable fun along the way.

Summary

Communicating across knowledge boundaries is challenging. People within a field learn specific, technical language and concepts that they take for granted, making it hard to communicate effectively across fields (e.g., Dougherty, 1992); and the same has been found for membership in a given organization or site (Sole & Edmondson, 2002). Overcoming these hurdles offers the potential to enrich individual perspectives on both sides of any knowledge divide, whether between disciplines or organizations. Moreover, collaborative research lends itself to conversations about practice because it is the phenomena under study collaborators have in common.

Discussion

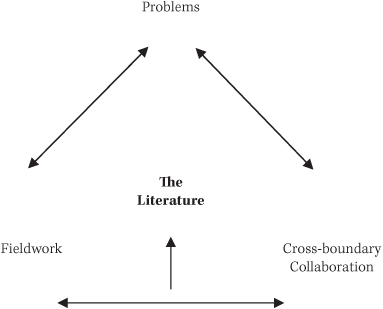

This chapter presents an approach to conducting research that informs theory and practice—an approach characterized by collaborating across boundaries to study problems in field settings. Although this approach has been presented as separate choices, the interrelatedness among them is undeniable. Researchers motivated by an important problem are enabled in their efforts to understand it by time spent in the field. Fieldwork puts problems in rich, complex contexts, revealing their multiple facets and facilitating fortuitous connections that may give rise to new theories and new ideas for practice. And, time spent in the field and with practitioners reveals new, interesting problems that are difficult to detect by reading the literature alone. Likewise, real problems in organizations are unlikely to be explained adequately by analysis within a single discipline; different disciplines, bringing the attention of actors with different perspectives, working together often provide new insights into existing problems. Finally, collaborating across academic boundaries sometimes reveals problems that might go unnoticed by researchers in one field—the problem of differences in error reporting across hospital units surfaced by importing a social psychological lens into the medication error study. Figure 2.1 thus depicts these three elements with mutually reinforcing relationships.

Despite the interrelatedness shown in Figure 2.1, every project need not emphasize all three elements equally. The level of collaboration may be higher or lower, the degree to which a problem takes center stage in motivating the work, and the extent of time spent in the field all may vary across projects depending on the question and the context. My argument is merely that these elements help tie researchers to practice in different ways.

Using the Literature

The literature—that is, prior research that informs and shapes the research question—plays a crucial role in helping to keep these elements working together for research purposes. The literature is an integrating force, helping to shape research to make its best contribution. Familiarity with what has come before in a given field that relates to your research question makes sure prior findings are integrated, elaborated, or refuted in the current work. More specifically, with respect to understanding a problem, finding out what others have done to understand that problem lowers the risk of reinventing the wheel.

Prior research in a field of inquiry informs and shapes one’s research question; this statement is just as applicable for researchers who aspire to inform practice as for those who consider advancing theory their sole aim. Field research that produces novel contributions to the literature requires careful thought about methods that fit the current state of knowledge. For instance, new areas of research require qualitative data to explore and identify dimensions of interest and possible relationships among them, while more mature streams benefit from quantitative data and careful tests of hypotheses. In either case, the literature is crucial for shaping methodological and scope decisions, and hybrid approaches allow researchers to test associations between variables with quantitative data and to explain and illuminate novel constructs and relationships with qualitative data (Edmondson & McManus, 2007).

FIGURE 2.1 Relationships between Problems, Fieldwork, and Collaboration

When collaborating across academic disciplines, it is important to identify the literature one hopes to advance. The insights from different fields are likely to enrich one’s thinking, as previously noted, but then they must be tamed and focused. The literature provides a force to focus and sharpen what one has found, before communicating it to others. Focusing on the state of the literature helps to avoid the trap of the overly broad or superficial observation in favor of offering precise statements on the advance that has been made.

In this discussion of the role of the literature, it is not my intention to take a step away from the practical. To the contrary, understanding what has been discovered previously is an essential step toward useful research because it allows the best use of limited time and resources. Thus, the inclusion of the literature in the center of Figure 2.1 is meant to highlight its important role in doing research that informs theory and practice.

Rewards and Limitations

Problem-focused, field-based interdisciplinary research projects, by their very nature, present learning opportunities. Pursuing this approach makes it virtually impossible not to learn something new and interesting about work or about organizations. Moreover, if, as I have argued, it increases the chances of developing findings with implications for practice, the process thus provides an additional source of satisfaction. By getting to know the people for whom one’s ideas matter, one is both more able and more likely to generate implications for practice. By working across knowledge boundaries, one may develop a broader audience for one’s work.

There are, of course, important limitations to this approach. First, while organizational behavior lends itself to the study of real problems in the field and tolerates a certain level of boundary spanning, this approach may be more challenging in other, even closely related, disciplines such as social psychology, in which norms and methods are more orthodox. Second, data collected in naturalistic settings are almost always limited in important ways, including the nonrandom nature of the sample and the extent and timing of data collection (Edmondson & McManus, 2007). Working in the field can mean that a carefully planned time frame suffers due to constraints outside your control. Third, there is a risk that research following this strategy may be labeled as “too applied.” Critics may view the work as mere application of theory rather than as a theoretical contribution. Fourth, and perhaps most important to guard against while building a scholarly career, it may be easy to chase too varied an agenda, developing superficial rather than deep expertise.

Conclusion

The studies discussed in this chapter were conducted with the aspiration to produce useful knowledge. Barriers remain, however. More must be done to communicate and work with practitioners to facilitate translation from research findings to actionable practice. These findings, for the most part, have presented starting points for further experimentation and adjustment rather than concrete recommendations for action. To illustrate, I showed that psychological safety is measurable, varies systematically across groups, and affects speaking up and learning (Edmondson, 1996, 1999), and that people in leadership positions affect the psychological safety of others (Edmondson, 2003b; Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006). Good managers may understand this intuitively, but methods for helping others understand and act on this knowledge remain undeveloped. Similar arguments can be made for our findings that clinical practices that have a stronger evidence base are more likely to be successfully implemented (Tucker, Nembhard, & Edmondson, 2007) or that leaders who frame a change process in ways that take group dynamics into account increase the chances that disruptive new technologies will be accepted in the organization (Edmondson, 2003a). For our findings showing that people in hierarchies think about speaking up in counterproductive ways, Jim Detert and I have only begun to consider what managers might do to ameliorate these effects (Detert & Edmondson, 2011). Finally, as discussed, Diana Smith and I found that simmering relationship conflicts in a team that are not addressed impede progress on the task—and that addressing them effectively is both desirable and feasible (Edmondson & Smith, 2006). However, it may take an interventionist with the extraordinary skill that Smith brings—after decades of practice—to put this knowledge into action.

In conclusion, many paths may lead scholars toward useful research. The approach and the work discussed in this chapter are by no means the only or the best route to take. The work, the journey, has been engaging and satisfying, especially in terms of the people I have had the chance to work with, the ideas we have had the privilege to explore, and the potential—that occasionally feels within reach—for making a difference in organizations that operate in and affect the world in smaller and larger ways.

REFERENCES

Amason, A. (1996). Distinguishing the effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict on strategic decision making: Resolving a paradox for top management teams. Academy of Management Journal, 39(1), 123–148.

Argyris, C. (1980). Making the undiscussable and its undiscussability discussable. Public Administration Review, 40(3), 205–213.

Argyris, C. (1982). Reasoning, learning, and action: Individual and organizational. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for action: A guide to overcoming barriers to organizational change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Argyris, C., Putnam, R., & Smith, D. (1988). Action science. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Baer, M., & Frese, M. (2003). Innovation is not enough: Climates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(1), 45–68.

Baldwin, J. (1996). BuckyWorks: Buckminster Fuller’s ideas for today. New York: Wiley.

Clark, A. (1980). Action research: Theory, practice, and values. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 1, 151–157.

Detert, J., & Edmondson, A. (2011). Implicit theories of voice: Taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal (forthcoming).

Dougherty, D. (1992). Interpretive barriers to successful product innovation in large firms. Organization Science, 3(2), 179–202.

Edmondson, A. (1987). A Fuller explanation. Boston: Birkhauser.

Edmondson, A. (1996). Learning from mistakes is easier said than done: Group and organizational influences on the detection and correction of human error. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 32(1), 5–28.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 350–383.

Edmondson, A. (2002). The local and variegated nature of learning in organizations: A group-level perspective. Organization Science, 13(2), 128–146.

Edmondson, A. (2003a). Framing for learning: Lessons in successful technology implementation. California Management Review, 45(2), 34–54.

Edmondson, A. (2003b). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419–1452.

Edmondson, A. C. (2004). Learning from failure in health care: Frequent opportunities, pervasive barriers. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(6), 3–9.

Edmondson, A., Bohmer, R., & Pisano, G. (2001a). Disrupted routines: Team learning and new technology adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 685–716.

Edmondson, A., Bohmer, R., & Pisano, G. (2001b). Speeding up team learning. Harvard Business Review, 79(9), 125–134.

Edmondson, A., & Hajim, C. (2003). Safe to say at Prudential Financial. Harvard Business School case #9-603-093.

Edmondson, A., & McManus, S. E. (2007). Methodological fit in management field research. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1155–1179.

Edmondson, A., Roberto, M., Bohmer, R., Ferlins, E., & Feldman L. (2005). The recovery window: Organizational learning following ambiguous threats. In M. Farjoun & W. Starbuck (Eds.), Organization at the limits: NASA and the Columbia disaster (pp. 220–245). London: Blackwell.

Edmondson, A., Roberto, M., & Tucker, A. (2002). Children’s Hospital and Clinics. Harvard Business School case #9-302-050.

Edmondson, A., & Smith, D. M. (2006). Too hot to handle? How to manage relationship conflict. California Management Review, 49(1), 6–31.

Fox, N. (2003). Practice-based evidence: Towards collaborative and transgressive research. Sociology, 37(1), 81–102.

Greenwood, D., & Levin, M. (1998). Action research, science, and the co-optation of social research. Studies in Cultures, Organizations, and Societies, 4, 237–261.

Hackman, R., & Edmondson, A. (2007). Groups as agents of change. Handbook of organizational development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Jehn, K. (1997). A qualitative analysis of conflict types and dimensions in organizational groups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(3), 530–557.

Kenner, H. (1973). Bucky: A guided tour of Buckminster Fuller. New York: William Morrow.

Leape, L. (1999, January 12). Faulty systems, not faulty people. The Boston Globe.

Leape, L. (2007, August 23). Why pay for mistakes? The Boston Globe.

Levin, D., & Cross, R. (2004). The strength of weak ties you can trust: The mediating role of trust in effective knowledge transfer. Management Science 50(11), 1477–1490.

Lewin, K. (1945). The Research Center for Group Dynamics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Sociometry, 8(2), 126–136.

Miner, J. (2002). Organizational behavior: Foundations, theories, and analyses. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nembhard, I., & Edmondson, A. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(7), 941–966.

Pisano, G. (1996). The development factory: Unlocking the potential of process innovation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Pisano, G., Bohmer, R., & Edmondson, A. (2001). Organizational differences in rates of learning: Evidence from the adoption of minimally invasive cardiac surgery. Management Science, 47(6), 752–768.

Schein, E. (1987). Process consultation. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Schwarz, R. (1994). The skilled facilitator: Practical wisdom for developing effective groups. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Shortell, S., & Singer, S. (2008). Improving patient safety by taking systems seriously. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299(4), 445–447.

Smith, D. M. (2008). Divide or conquer: How great teams turn conflict into strength. New York: Portfolio.

Sole, D., & Edmondson, A. (2002). Situated knowledge and learning in dispersed teams. British Journal of Management, 13, S17–S34.

Tucker, A. L., Nembhard, I., & Edmondson, A. C. (2007). Implementing new practices: An empirical study of organizational learning in hospital intensive care units. Management Science, 53(6), 894–907.

Wageman, R., Hackman, R., & Lehman, E. (2005). The team diagnostic survey: Development of an instrument. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(4), 373–398.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amy C. Edmondson, Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School, studies leadership, teams, and organizational learning. Her recent publications include “Methodological Fit in Management Field Research” (Academy of Management Review, 2007). She received her PhD in organizational behavior from Harvard University in 1996. Before her academic career, Edmondson was Director of Research at Pecos River Learning Centers, where she worked on organizational change programs in a variety of Fortune 100 companies. In the early 1980s, she was Chief Engineer for architect-inventor Buckminster Fuller, and her book A Fuller Explanation clarifies Fuller’s mathematical contributions for a nontechnical audience.