Chapter 14. Advanced Editing

Stumble around in iMovie long enough, and you’ll be able to figure out most of its inner workings. But in this chapter, you’ll read about another level of capability, another realm of power and professionalism, that would never occur to most people.

This brief chapter covers advanced editing theory. Where the preceding chapters covered the technical aspects of editing video in iMovie—what keys to press, where to click, and so on—this chapter is about the artistic aspects of video editing. It covers when to cut, what to cut to, and how to create the emotional impact you want.

The Power of Editing

The editing process is crucial to any kind of movie, from home videos to Hollywood thrillers. Clever editing can turn a troubled movie into a successful one, or a boring home movie into one that, for the first time, family members don’t interrupt every 3 minutes by lapsing into conversation.

You, the editor, are free to jump from camera to camera, angle to angle, from one location or time to another, and so on. Today’s audiences accept that you’re telling a story. They don’t stomp out in confusion because one minute James Bond is in his London office, and then shows up in Venice a split second later.

You can also compress time, which is one of editing’s most common duties. (That’s fortunate, because most movies tell stories that, in real life, would take days, weeks, or years to unfold.) You can also expand time, making 10 seconds stretch out to 6 minutes—a technique familiar to anyone who’s ever watched a bomb’s digital timer tick down the seconds as the hero races to defuse it.

Editing boils down to choosing which shots you want to include, how long each shot lasts, and in what order they should play.

Modern Film Theory

If you’re creating a rock video or an experimental film, you can safely chuck all the advice in this chapter—and in this book. But if you aspire to make good “normal” movies, designed to engage or delight your viewers rather than to shock or mystify them, you should become familiar with the fundamental principles of film editing that have shaped virtually every Hollywood movie (and even most student and independent films) over the last 75 years. For example:

Tell the Story Chronologically

Most movies tell a story from beginning to end. This part is probably instinct, even if you’re making home movies. Arrange your clips roughly in chronological order, except when you want to represent your characters’ flashbacks and memories, or when you deliberately want to play a chronology game, as in Pulp Fiction.

Try to be Invisible

These days, an expertly edited movie is one where the audience isn’t even aware of the editing. This principle has wide-ranging ramifications. For example, the simple cut is by far the most common joint between film clips because it’s so unobtrusive. Using, say, the Circle Open transition between alternate lines of the vows at somebody’s wedding would hardly qualify as invisible editing.

Within a single scene, use simple cuts, not transitions. Try to create the effect of seamless real time, making the audience feel as though it’s witnessing the scene in its entirety, from beginning to end. This kind of editing is more likely to make your viewers less aware that they’re watching a movie.

Develop a Shot Rhythm

Every movie has an editing rhythm that’s established by the lengths of its shots. The prevailing rhythm of Lincoln, for example, is extremely different from that of The Bourne Identity. Every scene in a movie has its own rhythm, too.

As a general rule, linger less on closeup shots, but give more time to establishing wide shots. (After all, in an establishing shot, there are many more elements for the audience to study and notice.) Similarly, change the pacing of the shots according to the nature of the scene. Most action scenes feature very short clips and fast edits. Most love scenes include longer clips and fewer changes of camera angle.

Maintain Continuity

As a corollary to the notion that the audience should feel that they’re part of the story, professional editors strive to maintain continuity during the editing process. This continuity business applies mostly to scripted films, not home movies. Still, knowing what the pros worry about makes you a better editor, no matter what kind of footage you work with.

Continuity refers to consistency in the following:

The picture. Suppose we watch a guy with wet hair say, “I’m going to have to break up with you.” We cut to his girlfriend’s horrified reaction, but when we cut back to the guy, his hair is dry. That’s a continuity error, a frequent by-product of having spliced together footage that was filmed at different times. Every Hollywood movie, in fact, has a person whose sole job is to watch out for errors like this during the editing process.

Direction of travel. To make edits as seamless as possible, film editors and directors try to maintain continuity of direction from shot to shot. That is, if the hero sets out crawling across the Sahara from right to left to be with his true love, you better believe that when we see him next, hours later, he’ll still be crawling from right to left. This general rule even applies to much less dramatic circumstances, such as car chases, plane flights, and even people walking to the corner store. If you see a character walk out of the frame from left to right in Shot A, you’ll see her approach the corner store’s doorway from left to right in Shot B.

The sound. In an establishing shot, suppose we see hundreds of men in a battlefield trench, huddled for safety as bullets fly and bombs explode all around them. Now we cut to a closeup of two of these men talking, but the sounds of the explosions are missing. That’s a sound continuity error. The audience is certain to notice that hundreds of soldiers were issued a cease-fire just as these two guys started talking.

The camera setup. In scenes of conversations between two people, it would look really bizarre to show one person speaking only in closeup, and his conversation partner filmed in a medium shot. (Unless, of course, the first person were filmed in extreme closeup—just the lips filling the screen—because the filmmaker is trying to protect his identity.)

Gesture and motion. If one shot begins with a character reaching down to pick up the newspaper from her doorstep, the next shot—a closeup of her hand closing around the rolled-up paper, for example—should pick up from the exact moment where the previous shot ended. And as the rolled-up paper leaves our closeup field of view, the following shot should show her straightening into an upright position. Unless you’ve made the deliberate editing decision to skip over some time from one shot to the next (which should be clear to the audience), the action should seem continuous from one shot to the next.

Tip

When filming scripted movies, directors always instruct their actors to begin each new scene’s action with the same gesture or motion that ended the last shot. Having two copies of this gesture, action, or motion—one on each end of each take—gives the editor a lot of flexibility when it comes time to piece the movie together.

This principle explains why it’s extremely rare for an editor to cut from one shot of two people to another shot of the same two people (without inserting some other shot between them, such as a reaction shot or a closeup of one person or the other). The odds are small that, as the new shot begins, both actors will be in precisely the same body positions they were in when the previous shot ended.

When to Cut

Some Hollywood directors may tell their editors to make cuts just for the sake of making the cuts come faster, in an effort to pick up the movie’s pace. More seasoned directors and editors, however, usually adopt a more classical view of editing: Cut to a different shot when it’s motivated. That is, cut when you need to cut, so that you can convey new visual information by taking advantage of a different camera angle, switching to a different character, providing a reaction shot, and so on.

Editors look for a motivating event that suggests where they should make the cut, too, such as a movement, a look, the end of the sentence, or the intrusion of an off-camera sound that makes us want to look somewhere else in the scene.

Choose the Next Shot

As you read elsewhere in this book, the final piece of advice when it comes to choosing when and how to make a cut is this: Cut to a different shot. If you’ve been filming the husband, cut to the wife; if you’ve been in a closeup, cut to a medium or wide shot; if you’ve been showing someone looking off-camera, cut to what she’s looking at.

Avoid cutting from one shot of somebody to a similar shot of the same person. Doing so creates a jump cut, a disturbing and seemingly unmotivated splice between shots of the same subject from the same angle.

Video editors sometimes have to swallow hard and perform jump cuts for the sake of compressing a long interview into a much shorter sound bite. Customer testimonials on TV commercials frequently illustrate this point. You’ll see a woman saying, “Wonderglove changed…[cut] our lives, it really did…[cut] My husband used to be a drunk and a slob…[cut] but now we have Wonderglove.” (Often, directors apply a fast cross dissolve to the cuts in a futile attempt to make them less noticeable.)

However, as you can probably attest if you’ve ever seen such an ad, that kind of editing is rarely convincing. As you watch it, you can’t help wondering exactly what was cut and why. (The editors of 60 Minutes and other documentary-style shows edit the comments of their interview subjects just as heavily but conceal it better by cutting away to reaction shots—of the interviewer, for example—between edited shots.)

Popular Editing Techniques

Variety and pacing play a role in every decision a video editor makes. The following sections explain some common tricks of professional editors that you can use in iMovie.

Tight Editing

One of the first tasks you’ll encounter when editing your footage is choosing how to trim and chop up your clips, as described in Chapter 5. Even when you edit home movies, consider the Hollywood guideline for tight editing: Begin every scene as late as possible, and end it as soon as possible.

In other words, suppose the audience sees the heroine receiving the call that her husband has been in an accident, and then hanging up the phone in shock. We don’t really need to see her putting on her coat, opening the apartment door, locking it behind her, taking the elevator to the ground floor, hailing a cab, driving frantically through the city, screeching to a stop in front of the hospital, and finally leaping out of the cab. In a tightly edited movie, she would hang up the phone and then we’d see her leaping out of the cab (or even walking into her husband’s hospital room).

Keep this principle in mind even when editing your own, slice-of-life videos. For example, a very engaging account of your ski trip could begin with only three shots: an establishing shot of the airport; a shot of the kids piling into the plane; and then the tumultuous, noisy, trying-on-ski-boots shot the next morning. You get less reality with this kind of tight editing, but much more watchability.

Variety of Shots

Variety is important in every aspect of filmmaking—variety of shots, locations, angles, and so on. Consider the lengths of your shots, too. In action sequences, you may prefer quick cutting, where each clip in your movie track is only a second or two long. In softer, more peaceful scenes, longer shots may set the mood more effectively.

Establishing Shots

Almost every scene of every movie and every TV show—even the nightly news—begins with an establishing shot: a long-range, zoomed-out shot that shows the audience where the action is about to take place.

Now that you know something about film theory, you’ll begin to notice how often TV and movie scenes begin with an establishing shot. It gives the audience a feeling of being there and helps them understand the context for the medium shots or closeups that follow. Furthermore, after a long series of closeups, consider showing another wide shot, to remind the audience of where the characters are and what the world around them looks like.

As with every film-editing guideline, this one is occasionally worth violating. For example, in comedies, a new scene may begin with a closeup instead of an establishing shot, so that the camera can then pull back to make the establishing shot the joke. (For example: Closeup on main character looking uncomfortable; camera pulls back to reveal that we were looking at him upside down as he hangs, tied by his feet, over a pit of alligators.) In general, however, setting up any new scene with an establishing shot is the smart—and polite—thing to do for your audience’s benefit.

Cutaways and Cut-Ins

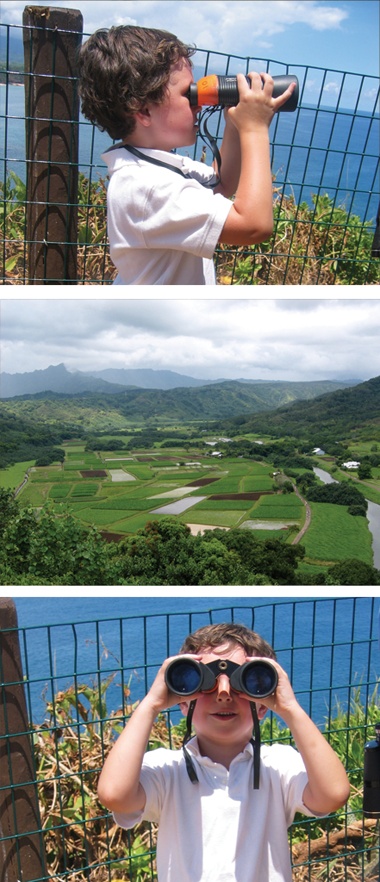

Cutaways and cut-ins are extremely common and effective editing techniques. Not only do they add some variety to a movie, but they let you conceal enormous editing shenanigans. By the time your movie resumes after the cutaway shot, you can have deleted enormous amounts of material, switched to a different take of the same scene, and so on. Figure 14-1 shows the idea.

The cut-in is similar, but instead of showing a different person or a reaction shot, it usually features a closeup of what the speaker is holding or talking about—a very common technique in training tapes and cooking shows.

Reaction Shots

One of the most common sequences in Hollywood history is a three-shot sequence that goes like this: First, we see the character looking offscreen; then we see what he’s looking at (a cutaway shot); and finally, we see him again so that we can read his reaction. This sequence is repeated so frequently in commercial movies that you can feel it coming the moment the performer looks off the screen.

From the editor’s standpoint, of course, the beauty of the three-shot reaction is that the middle shot can be anything from anywhere. That is, it can be footage shot on another day in another part of the world, or even from a different movie entirely. The ritual of character/action/reaction is so ingrained in our brains that the audience believes the actor was looking at the action, no matter what it is.

In home-movie footage, you may have been creating reaction shots without even knowing it. But you’ve probably been capturing them by panning from your kid’s beaming face to the petting-zoo sheep and then back to the face. You can make this sequence look great in iMovie by just snipping out the pans, leaving you with crisp, professional-looking cuts.

Parallel Cutting

When you make a movie that tells a story, it’s sometimes fun to use parallel editing or intercutting. That’s when you show two trains of action simultaneously and you keep cutting back and forth to show the parallel simultaneous action. In Fatal Attraction, for example, the intercut climax shows main character Dan Gallagher (Michael Douglas) downstairs in the kitchen, trying to figure out why the ceiling is dripping, even as his psychotic mistress Alex (Glenn Close) is upstairs attempting to murder his wife in the bathtub. If you’re making movies that tell a story, you’ll find this technique an exciting one when you’re trying to build suspense.