1. There’s Only One Planet Earth

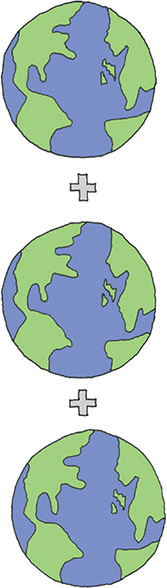

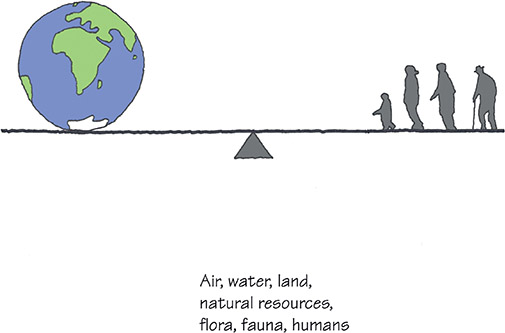

There is only one earth, and its ability to support an ever-increasing human population is limited. Based on today’s rate of consumption, we need one and a half earths to provide all our resources and to absorb our waste and CO2. We are treating the planet like an overdrawn bank account. At this rate, by 2050 we would need the support of three earths, which we do not have. There is an ethical duty to design the built environment to operate within the planet’s means, and to a minimum ecological footprint.

Links with all other Rules

Links with all other Rules

Rule 1

2. Sustainability Means Thinking about Tomorrow Today

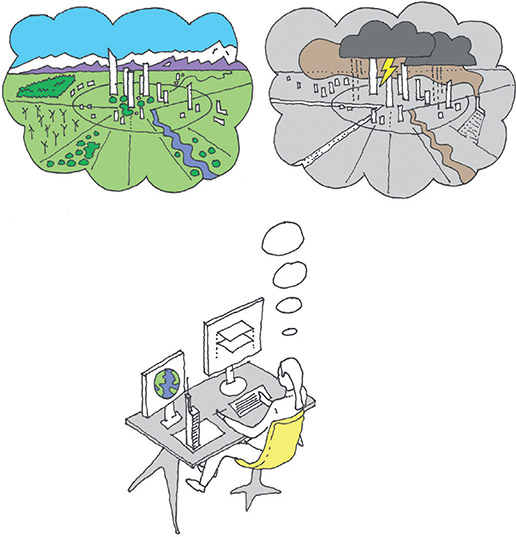

Our decisions and actions as designers today will have an impact on the planet for future generations. The designer’s goal is the improved long-term quality of both human life and of supporting ecosystems. Make all decisions with future generations in mind.

Links with rules 1, 12, 15, 19, 20, 22, 37, 45, 54, 69, 76

Links with rules 1, 12, 15, 19, 20, 22, 37, 45, 54, 69, 76

Rule 2

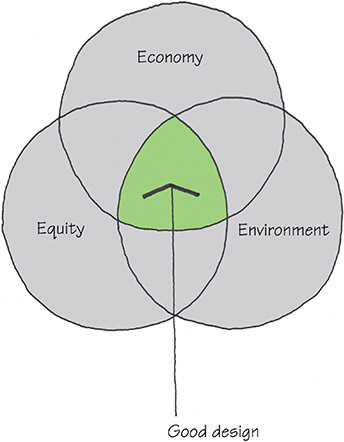

3. Economy, Equity, Environment: The Three Pillars of Sustainability

These three pillars of sustainability are known as the ‘three Es’. All of society benefits from buildings that are affordable to procure and functional to operate, now and into the future. Society must need and want development for it to be inclusive, it must have cultural and historical relevance and it must be joyful and useful to all. And because good design is enduring, it always seeks to protect and enhance the environment and its ecosystems.

Links with rules 1, 5, 7, 8, 45, 75, 83, 94

Links with rules 1, 5, 7, 8, 45, 75, 83, 94

Rule 3

4. Sustainable Design is a Method, Not a Style

Buildings and cities will only be sustainable if we set out intentionally to make them so, and this requires an interdisciplinary understanding of the economic, social, environmental and technical issues to be applied from the outset. Once a building has been designed, it is too late to make it sustainable: bolt-on features and gadgets that contribute little or nothing of environmental value are known as ‘eco-bling’, and they are often merely boastful. Set out to make buildings sustainable, or else they will not be.

Links with rules 1, 5, 6, 45, 89, 95

Links with rules 1, 5, 6, 45, 89, 95

Rule 4

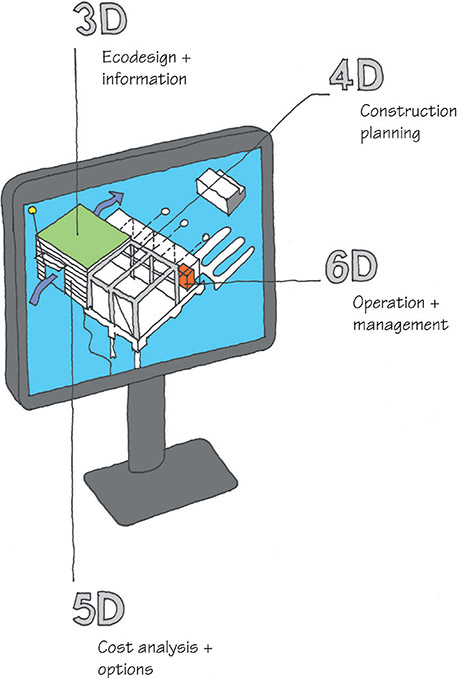

5. Sustainable Design is 6-Dimensional

A sustainable building is holistic, conceived with its whole life in mind. The effectiveness of its environmental design qualities, as well as its environmental impacts, can be examined during the design stages. This is possible because traditional 2D drawings have become intelligent 3D virtual models, in which time is the 4th dimension and the lifetime cost of our decisions is the 5th. In a 6D model, the as-built project information would become available to the owner in order to enable sustainable operation of the building. Innovate with the available tools, to create sustainable environments–design in six dimensions.

Links with rules 1, 3, 4, 6, 15, 23, 26, 33–37, 38, 42, 45, 69, 75

Links with rules 1, 3, 4, 6, 15, 23, 26, 33–37, 38, 42, 45, 69, 75

Rule 5

6. How ‘Green’ is Your Building?

‘Green’ means sustainable, but there are many shades of green. A ‘light-green’ building will target a few of these rules of thumb. A ‘deep-green’ building will successfully adopt most of them. Aim for the deepest green possible. A deep-green building will:

- Have a highly energy-efficient envelope

- Be a net producer of energy and a zero-carbon emitter

- Optimise use of resources and embodied energy

- Minimise water use and waste

- Be healthy and non-polluting

- Be long lasting, adaptable and easy to dismantle

Links with rules 1, 4, 5, 10, 11, 12, 19, 23, 26, 33–37, 38, 42, 45, 72, 73, 74

Links with rules 1, 4, 5, 10, 11, 12, 19, 23, 26, 33–37, 38, 42, 45, 72, 73, 74

Rule 6

7. What on Earth is the Environment?

The ancient Greeks did not have the word ‘environment’. The word as we use it today is relatively new: coined during the Industrial Revolution, its meaning is linked to humankind’s influence on the planet. To design with environmental sensitivity, we must first know what the environment is: it consists of all elements of the physical and biological world and the interrelationships between them.

Links with rules 1, 3, 8, 45

Links with rules 1, 3, 8, 45

Rule 7

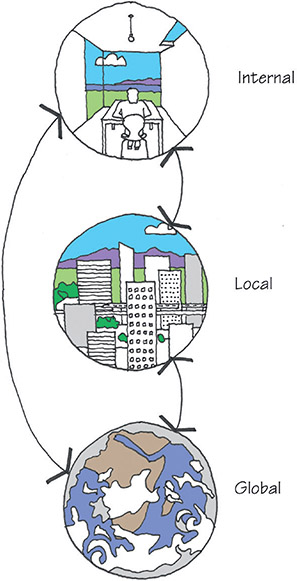

8. There are Different Scales of Environment

The environment in which we live constitutes not only our immediate surroundings; it is important to remember that it exists simultaneously at a global, local and a building-interior scale. Designers and occupiers of buildings and cities operate in each of the scales of the environment at all times.

Links with rules 1, 3, 7, 9, 45

Links with rules 1, 3, 7, 9, 45

Rule 8

9. What you do Locally has an Effect Globally

If we design a dwelling, we might think we are chiefly concerned with the building’s interior environment, as well as interaction with the immediate local environment. But heating or cooling may be needed, resulting in CO2 emissions, contributing to global warming, affecting the global environment in a chain reaction. The scales of environment are connected: when someone simply switches on a light at home or at work they become a link in that global chain.

Links with rules 1, 8, 15, 45, 67

Links with rules 1, 8, 15, 45, 67

Rule 9

10. The Greenest Building may be the One that isn’t Built

We might have a choice about whether we build, restructure, share or change our lives in some way. Consider all options carefully in order to establish the one that best matches needs with environmental impacts. Sometimes the decision not to build a new building is the greenest one.

Links with rules 1, 6, 11, 12, 45

Links with rules 1, 6, 11, 12, 45

Rule 10

11. The Greenest Building may be the One that is Already Built

An existing building converted to a new use or upgraded in terms of energy technologies, insulation standards and ventilation performance may provide a healthy, low-energy-use, productive and high-quality spatial environment where one did not exist before, often cost-effectively. If operating energy can be significantly reduced, refurbishment is likely to be the lowest-carbon solution–and the retention of existing fabric can contribute to the quality of the public realm. Too many of our cities’ buildings are empty too much of the time: seek innovative long-term, temporary or multiple uses for under-utilised buildings.

Links with rules 1, 6, 10, 24, 25, 38, 45, 76, 86

Links with rules 1, 6, 10, 24, 25, 38, 45, 76, 86

Rule 11

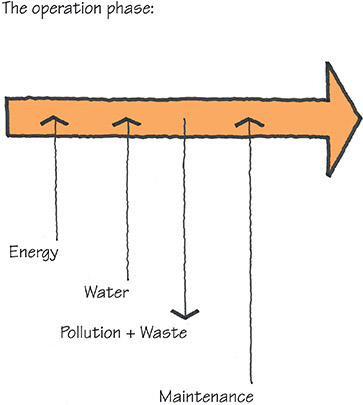

12. The Decision to Build is a Long-Lasting One

It takes time to design and construct a sustainable building or city, but once complete the built environment will last much longer than those few years–perhaps 100 years or more in the case of a building. So the designer’s early decisions are important, long-lasting ones with major environmental impacts during the operational phase of a building’s life. Make sure you get them right by following the rules of thumb.

Links with rules 1, 2, 6, 10, 13, 19, 45, 69

Links with rules 1, 2, 6, 10, 13, 19, 45, 69

Rule 12

13. ‘Long Life, Loose Fit, Low Energy’

This saying, a rallying cry for champions and designers of the built environment, has its prophetic origins just before the major world oil crisis of the early 1970s. Consider longevity, flexibility and energy efficiency as the cornerstones of a sustainable architecture. Remember that ‘soft’ elements and internal finishes will be replaced fairly regularly, services each 10–20 years, fabric elements each 20–30 years and major changes might occur every 30–75 years of a building’s life. Each time they do, environmental and low-energy upgrades should also be made.

Links with rules 1, 12, 19, 26, 45, 69, 85

Links with rules 1, 12, 19, 26, 45, 69, 85

Rule 13

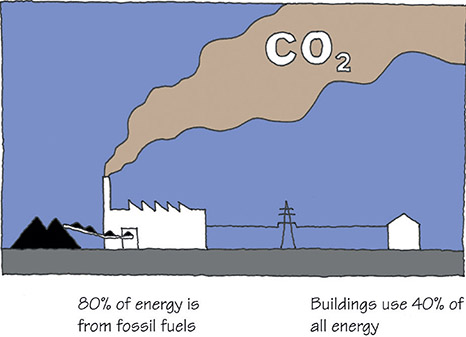

14. To Reduce CO2 Emissions, Reduce Fossil-Fuel Use

More than 80% of global energy demand is supplied from fossil fuels. Most of the rapid increase in the concentration of CO2 in the earth’s atmosphere took place due to industrialisation in the last 150 years, and half of CO2 from human sources (anthropogenic, rather than natural CO2) is not reabsorbed in the carbon cycle. As a ‘greenhouse gas’, it is linked with global warming and climate change. Around half of the UK’s CO2 emissions derive from the construction and operation of buildings.

Links with rules 1, 15, 16, 18, 26, 45, 55, 86

Links with rules 1, 15, 16, 18, 26, 45, 55, 86

Rule 14

15. Buildings Influence Global Warming

We use half of the world’s energy to heat, cool, light, ventilate and power our buildings. Much of that energy is derived from fossil fuels, with the result that our buildings are responsible for 40% of all CO2 emissions, contributing to global warming and climate change. We must cut the energy consumption of our buildings as part of the fight against global warming.

Links with rules 1, 2, 5, 9, 14, 16, 17, 25, 45, 85, 91

Links with rules 1, 2, 5, 9, 14, 16, 17, 25, 45, 85, 91

Rule 15

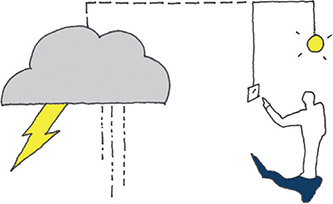

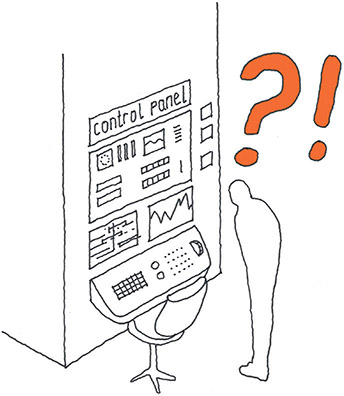

16. In Fact, Buildings don’t Use Energy; People Do

We often hear that buildings use around half of all global energy produced, but the occupants of a building have a major influence on its performance. A poorly designed building will use more energy than a well-designed, low-energy-use building whatever its occupants do, but enabling the user to know where energy is being used, and making it easy to control its use, are key to reduced energy consumption.

Links with rules 1, 14, 15, 24, 45, 67, 68

Links with rules 1, 14, 15, 24, 45, 67, 68

Rule 16

17. Break the Urban Vicious Cycle

Since the year 2000, for the first time in the history of humanity more of us live in cities than live in rural locations. This trend will continue, increasing stresses on our urban environments, on people and on the planet. Cities produce 75% of the world’s greenhouse gases, and global warming is likely to result in increased energy consumption: a vicious cycle results as unpredictable, extreme climate conditions lead to increased energy use, resulting in more greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions, leading to further changes in climate. We must reduce emissions from our urban environments by intelligent planning and the retrofitting of transportation systems, utilities and buildings.

Links with rules 1, 15, 18, 45, 55, 58, 59, 80, 99

Links with rules 1, 15, 18, 45, 55, 58, 59, 80, 99

Rule 17

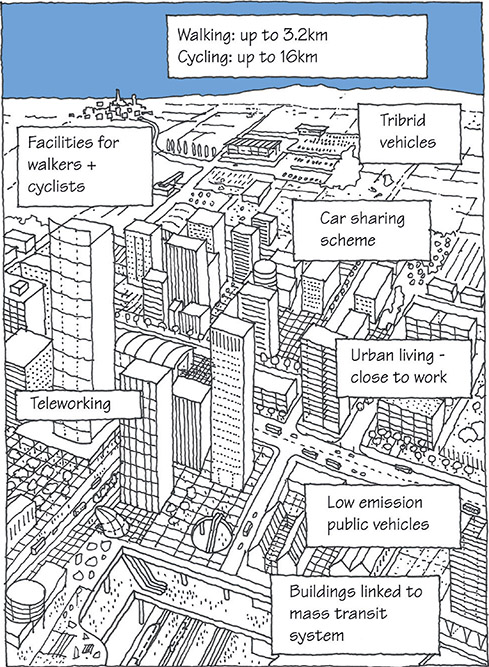

18. Sustainable Environments Need Sustainable Transport

Buildings are responsible for half of all human-generated greenhouse gases, but half of the remainder derives from the transportation of people and products between buildings and within and around cities. An efficient public mass-transportation system linked with compact, mixed-use urban design reduces energy consumption, pollution and greenhouse-gas emissions. Good planning encourages walking and cycling–and working from home twice a month reduces emissions by 10%. For out-of-town developments, transport-generated carbon can be higher than that generated by the operation of buildings, so a sustainable transport system is imperative.

Links with rules 1, 14, 17, 45, 51, 77, 81, 83, 101

Links with rules 1, 14, 17, 45, 51, 77, 81, 83, 101

Rule 18

19. Design for Adaptability

A building must be designed such that it can be adapted for future, unknown needs. Adaptability, built in at the outset, will enable future users to extend the building’s life, take advantage of new technologies and modify its spaces, environments and structures to respond to changing requirements. Without adaptability, a building soon outlives its usefulness.

Links with rules 1, 2, 6, 12, 13, 45, 86

Links with rules 1, 2, 6, 12, 13, 45, 86

Rule 19

20. Design for Resilience

Climate change results in many uncommon conditions in all regions of the world, including increased rainfall, drought, more extreme weather events, warmer and colder temperatures, rising sea levels and floods, and the effects on materials of increased ultraviolet (U/V) radiation and insects. The response is clear: design buildings, cities and their connecting infrastructure to be resilient to predicted future changes in climatic conditions, including the conditions in which the construction itself will take place.

Links with rules 1, 2, 40, 45

Links with rules 1, 2, 40, 45

Rule 20

21. Go Off-Grid?

Almost one quarter of the world’s population lives without electricity, but this is often not by choice. It is possible (and sometimes necessary) in certain situations, locations and climate regions for buildings to be disconnected from national utilities and to become ‘autonomous’, or self-sufficient. The decision to go off-grid might be driven by the desire to save money, to reduce dependence on institutions and governments or, sometimes, to reduce carbon footprint. When choosing to live off-grid, aim to ensure no fossil fuels are used, including for transport in remote places, and that there are sustainable local sources of water and sewage treatment.

Links with rules 1, 28–30, 45, 91

Links with rules 1, 28–30, 45, 91

Rule 21