Chapter 9

Responding to External Pressures and Unforeseen Events

Shareholder Activism: Here to Stay

In the last 30 years, individual and institutional shareholders have found their voice. Today, they assert their power as the company’s owners in many ways—from selling their shares to private or public communication with management and the board, from press campaigns to blogging, from openly talking to other shareholders to putting forward shareholder resolutions, from weighing in on political contributions to curbing executive pay, and from calling shareholder meetings to seeking to replace the chief executive, individual directors or the entire board. In June 2012, Yahoo’s board—under pressure from activist shareholders—dismissed its CEO for lying on his resume. At about the same time, Walmart’s board was openly challenged for reelection by the powerful California State Teachers Retirement System in connection with an alleged bribery scandal the retailer was dealing with in Mexico. Earlier, in April 2012, Citigroup shareholders voted down CEO Vikram Pandit’s $15 million pay package at the bank’s shareholder meeting in Dallas.

Clearly, the prolonged downturn has played a role in the rise of more targeted shareholder activism. For many investors, voting has become an important avenue to express dissatisfaction with the performance of a specific company executive or member of the board of directors, and perhaps voicing a greater dissatisfaction with Wall Street’s overall role in the meltdown.

Lack of information historically posed a serious obstacle to small investors. The Internet and disclosure reforms passed by Congress over the past 10 years have changed that. Greater disclosure and the availability of that information online has made it a whole lot easier for shareholders to identify specific board members, find out which corporate committees they sit on, and how much they make for sitting on the board. That, in turn, has made it easier for activist shareholders to target specific board members who sit on key committees.

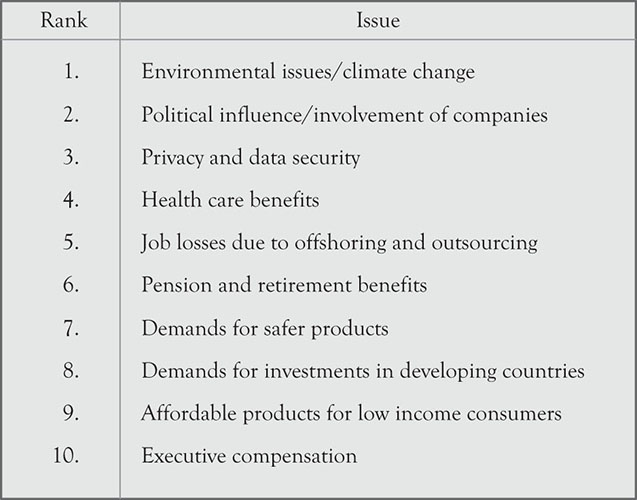

It appears that the growth in activism over the past 10 years has been led primarily by two groups: profit seekers and ideologists. In the first category are private equity groups and other big institutional investors. The second category mainly consists of social investors whose investment strategies are geared toward a cause. For example, shareholder activists increasingly target a company’s political activities, be it lobbying for legislation that benefits the company or donating to a candidate or party that supports specific legislation (Figure 9-1).

Figure 9-1. New issues for the board room.

Adapted from “Risk to Opportunity—How Global Executives View Sociopolitical Issues,” McKinsey Quarterly, Oct. 2008.

Although shareholder proxy proposals typically are not binding or may not receive enough votes to pass, they draw public attention to companies’ practices and often force them to reconsider their policies. As a result, a growing number of companies meet with their institutional shareholders during the planning stages of a proposal rather than wait until the implementation stage. And an increasing number of companies are submitting all-equity compensation plans for shareholder approval.

Not surprisingly, shareholder activism is controversial. Proponents argue that companies with active and engaged shareholders are more likely to be successful in the long term than those that largely function on their own. In their view, vigilant shareholders act as fire alarms, and their mere presence helps alleviate managerial or boardroom complacency. Opponents say that “shareholder activism” is a form of disruptive, uninformed, populist meddling that encourages short-term behavior and diverts a board from a focus on value creation. Some particularly worry about the rise of hedge-fund activism. They note that although hedge funds hold great promise as active shareholders, their intense involvement in corporate governance and control also potentially raises a major problem, namely, that the interests of hedge funds sometimes diverge from those of their fellow shareholders. These polar opposites reflect the broader societal disagreement about how much power shareholders should delegate to corporate boards and when direct shareholder action becomes necessary and on what terms.

Shareholder Proposals: The Key Issues

The most popular shareholder resolutions of the most recent proxy season concern issues such as majority voting, access to the proxy statement, declassifying boards, “entrenchment” devices (classified boards, poison pills, supermajority vote requirements, the right to call special shareholder meetings, among others) and, of course, compensation alignment and disclosure.

A decade ago, more than 60% of S&P 500 companies had staggered board terms, and plurality voting in director elections was widely accepted. Today, two-thirds of S&P 500 firms have declassified boards and nearly 80% of these companies have adopted majority voting provisions, as many boards have heeded shareholder votes for these reforms.

With a staggered board of directors a corporation elects its directors a few at a time, with different groups of directors having overlapping multiyear terms, instead of en masse, with all directors having 1-year terms. Each group of directors is put in a specified “class,” for example, Class I, Class II, and so on; hence staggered boards are also known as “classified boards.” In publicly held companies, staggered boards have the effect of making hostile takeover attempts more difficult because hostile bidders must win more than one proxy fight at successive shareholder meetings in order to exercise control of the target firm. Particularly in combination with a poison pill, a staggered board that cannot be dismantled or evaded is one of the most potent takeover defenses available to U.S. companies.

Under the plurality model, directors who receive the greatest number of favorable votes are elected. Shareholders cannot vote against director nominees but can only withhold or not cast their votes. Thus, most nominees are elected, even if they receive very few favorable votes and even if many votes are withheld or not cast. Under majority voting, to be elected, a nominee must get a majority of the votes cast. The states in which most U.S. public companies are incorporated make either of these models available to corporations.

As might be expected, the prevalence of majority voting and declassified boards is higher at large-cap companies, which are subject to more public scrutiny and generally have greater institutional ownership. However, there are some practices, such as independent board chairs, that remain more common at small and mid-cap firms. Directors on a typical S&P 500 board tend to be more independent, more diverse, and slightly older on average than at smaller-cap companies.

Another corporate governance issue that remains high on activists’ lists concerns shareholder proxy access in director elections. A few years ago, the SEC proposed new rules that would have allowed certain shareholders to place the names of director nominees in the company’s proxy solicitation materials and proxy card. However, after reviewing the proposal, it decided against enactment. Arguments against proxy access included that, under current law, shareholders are free to utilize the proxy rules to solicit votes for their own nominees in director elections. Another argument was that proxy access might allow special interest groups to unduly influence the election process. Not all shareholders have the same interests. Arguments in favor of proxy access were that it would diversify boards and give shareholders a more prominent voice in decision making. Earlier this year, however, the SEC reversed itself and announced that its revisions to the proxy rules to allow shareholders to propose proxy access bylaws and other election or nomination procedures will become effective shortly.

This means that U.S. public companies will not be subject to a mandatory proxy access standard but must permit shareholder proposals that either request that the board implement proxy access or that bypass the board and directly amend the company’s bylaws to implement proxy access. Some companies may want to consider proactively adopting their own proxy access standard rather than waiting for an activist shareholder to propose one. Others may decide to observe the development of market practices and trends before taking action. It is widely expected that it will take a number of years for market practices to develop, and it is not clear that proxy access will become common among public companies in the way that, say, majority voting has. Many companies and shareholders may determine that a proxy access regime would undermine the role of the nominating committee and that a combination of a strong, independent nominating committee, effective shareholder communication channels, and majority voting provisions makes proxy access unnecessary and undesirable.

As the 2012 proxy season drew to a close, it became clear that executive compensation issues, particularly “Say on Pay,” again dominated the headlines. Say on Pay is politically and emotionally appealing, attracts positive press, and, most important, is strongly supported by Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS; currently a part of RiskMetrics Group) and other proxy advisory firms. As with the issue of majority voting, given the strong national trend in favor of corporate governance activism and the obvious popular appeal of “Say on Pay,” momentum is building toward a pervasive “Say on Pay” regime for U.S. public companies.

The strong momentum for “Say on Pay” is, in part, explained by its international roots. The concept originated in the United Kingdom in the early 2000s and was made mandatory for London Stock Exchange (LSE)-listed companies by an amendment to the Companies Act in 2002. Mandatory shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation have since been legislatively adopted in Australia and Sweden. “Say on Pay” has also been implemented in the Netherlands and Norway in the form of a binding annual “vote of confidence” on executive compensation.

As a practical matter, for a U.S. company “Say on Pay” means that its executive pay policies and procedures will have to meet ISS guidelines on executive compensation or suffer a very strong risk of ISS recommending that shareholders vote “No on Pay.” Such a negative vote, if not addressed promptly by modifying executive compensation to fit ISS guidelines, will almost certainly lead to an ISS withhold-vote recommendation against the compensation committee and perhaps the entire board. The only clearly visible alternative to accepting ISS guidelines on executive compensation is for the board to negotiate exceptions with ISS based on particular facts and circumstances or with investors voting enough shares to overcome an ISS recommendation to vote “No on Pay.”

Looking ahead, there are indications that shareholders activists are shifting their focus to shareholder proposals for bylaw amendments to implement corporate governance reform in place of traditional nonbinding shareholder proposals that merely recommend board action. Two major reasons for this change in focus are the continued frustration with company boards that either fail to act in response to a successful nonbinding shareholder resolution or “water down” implementation of the proposal and a concern that boards can too easily amend or rescind board-adopted policies under the umbrella of fiduciary duty obligations.

Demands for Corporate Social Responsibility

Most of the pressure on boards in the last 25 years has come from shareholders. More recently, however, a different source of pressure—the demand for corporate social responsibility (CSR)—has emerged, which is forcing directors into new governance territory occupied by stakeholders other than shareholders. While pressure on corporate executives to pay greater attention to stakeholder concerns and make CSR an integral part of corporate strategy has been mounting since the early 1990s, such pressure is only now beginning to filter through to the board.

The emergence of CSR as a more prominent item on a board’s agenda reflects a shift in popular opinion about the role of business in society and the convergence of environmental forces, such as the following:

•Globalization. There are now more than 60,000 multinational corporations estimated to be operating in the world.1 Perceptions about the growing reach and influence of global companies has drawn attention to the impact of business on society. This has led to heightened demands for corporations to take responsibility for the social, environmental, and economic effects of their actions. It has also spawned more aggressive demands for corporations to set their sights on limiting harm and actively seeking to improve social, economic, and environmental circumstances.

•Loss of trust. High-profile cases of corporate financial misdeeds (Enron, WorldCom, and others) and of social and environmental irresponsibility (e.g., Shell’s alleged complicity in political repression in Nigeria; Exxon’s oil spill in Prince William Sound in Alaska; Nike’s and other apparel makers’ links with “sweatshop” labor in developing countries; questions about Nestlé’s practices in marketing baby formula in the developing world) have contributed to a broad-based decline in trust in corporations and corporate leaders. The public’s growing reluctance to give corporations the benefit of the doubt has led to intensified scrutiny of corporate impact on society, the economy, and the environment, and a greater readiness to assume—rightly or wrongly—immoral corporate intent.

•Civil society activism. The growing activity and sophistication of “civil society” organizations, many of which are oriented to social and environmental causes, has generated pressure on corporations to take CSR seriously.2 Well-known international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as Oxfam, Amnesty International, Greenpeace, the Rainforest Action Network, and the Fair Labor Association, have influenced corporate decision making in areas, such as access to essential medicines, labor standards, environmental protection, and human rights. The advent of the Internet has increased the capacity of these organizations—as well as a plethora of national and local civic associations—to monitor corporate behavior and mobilize public opinion.3

•Institutional investor interest in CSR. The growth in “socially responsible investing” has created institutional demand for equity in corporations that demonstrate a commitment to CSR. Recent growth in assets involved in socially responsible investing has outpaced growth in all professionally managed investment assets in the United States, even though the mainstream financial community has been slow to incorporate nonfinancial factors into its analyses of corporate value.4

These trends indicate that there is both a growing perception that corporations must be more accountable to society for their actions, and a growing willingness and capacity within society to impose accountability on corporations. This has profound implications for the future of corporate governance. It suggests that boards will soon have to deal with

•a growing pressure to give stakeholders a role in corporate governance;

•a growing pressure on corporations to disclose more and better information about their management of social, environmental, and economic issues;

•an increasing level of regulatory compulsion related to elements of corporate activity that are currently regarded as voluntary forms of social responsibility;

•a growing interest by the mainstream financial community in the link between shareholder value and nonfinancial corporate performance.

The discussion about corporate accountability to stakeholders, therefore, while often couched in the vocabulary of CSR, is really a discussion about the changing definition of corporate governance, which is why it should receive a greater priority on the board’s agenda.

Interestingly, whereas board agendas mostly focus on competition, cooperation may well become the preferred business strategy for addressing social and environmental issues. Increasingly, companies are joining forces not only with business competitors but also with human rights and environmental activists (formerly considered enemies), as well as socially responsible investors, academics, and governmental organizations. At the 2007 World Economic Forum (WEF) gathering, for example, two such coalitions were announced to address the issue of global online freedom of expression, particularly in repressive regimes. One, facilitated by Business for Social Responsibility (BSR), consists of companies facing intense criticism over complicity with suppressing online free speech in China. This coalition includes big names, such as Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo. The other gathered together socially responsible investing firms and human rights advocates, such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Reporters Without Borders.

Dealing with Hostile Takeovers

Corporate takeovers first became a prominent feature of the U.S. business landscape during the 1970s and 1980s. Hostile acquisitions generally involve poorly performing firms in mature industries and occur when the board of directors of the target is opposed to the sale of the company. In this case, the acquiring firm has two options to proceed with the acquisition—a tender offer or a proxy fight.

Tender Offers and Proxy Fights

A tender offer represents an offer to buy the stock of the target firm either directly from the firm’s shareholders or through the secondary market. The purchaser typically offers a premium price to encourage the shareholders to sell their shares. The offer has a time limit, and it may have other provisions that the target company must abide by if shareholders accept the offer. The bidding company must disclose its plans for the target company and file with the SEC. Sometimes, a purchaser or group of purchasers will gradually buy up enough stock to gain a controlling interest (known as a creeping tender offer), without making a public tender offer. This is risky because the target company could discover the attempted takeover and take steps to prevent it.

Because it allows bidders to seek control directly from shareholders—by going “over the heads” of target management—the tender offer is the most powerful weapon available to the hostile bidder. Indeed, just the threat of a hostile tender offer can often bring a recalcitrant target management to the bargaining table, especially if the bidder already owns a substantial block of the target’s stock and can demonstrably afford to finance a hostile offer for control. Although hostile bidders still need a formal agreement to gain total control of the target’s assets, this is often easily accomplished once the bidder has purchased a majority of voting stock.

When there are strong differences between a board and a company’s shareholders about the firm’s long-term strategy, its executive compensation policies, or a merger or acquisition proposal, a proxy fight is likely to ensue. This occurs when the board sends out its proxy statement in which it seeks shareholder approval for a variety of actions. Proxy contests are usually waged to replace members of the board of directors, but they can also be used to gain support in other efforts like an acquisition. They tend to involve publicly traded companies but can also target closed-end mutual funds.

A leveraged buyout (LBO) is a variation of a hostile takeover. In an LBO, the buyer borrows heavily to pay for the acquisition, either from traditional bank loans or through high-yield (junk) bonds. This can be risky, since incurring so much debt can seriously harm the value of the acquiring company.

Defense Mechanisms

The management and directors of target firms may resist takeover attempts either to get a higher price for the firm or to protect their own self-interests. The most effective methods are built-in defensive measures that make a company difficult to take over. These methods are collectively referred to as “shark repellents.” Here are a few examples:

•A golden parachute, or change-of-control agreement, discussed earlier, is an agreement that provides key executives with generous severance pay and other benefits in the event that their employment is terminated as a result of a change of ownership of the company. Golden parachutes are voted on by the board of directors and, depending on the laws of the state in which the company is incorporated, may require shareholder approval. Some golden parachutes are triggered even if the control of the corporation does not change completely; such parachutes open after a certain percentage of the corporation’s stock is acquired.

•The supermajority is a defense that requires 70% or 80% of shareholders to approve of any acquisition. This makes it much more difficult for someone to conduct a takeover by buying enough stock for a controlling interest.

•A staggered board of directors, discussed above, drags out the takeover process by preventing the entire board from being replaced at the same time. The terms are staggered, so that some members are elected every 2 years, while others are elected every 4 years. Many companies that are interested in making an acquisition are not willing to wait 4 years for the board to turn over.

•Dual-class stock allows company owners to hold onto voting stock, while the company issues stock with little or no voting rights to the public. This allows investors to purchase stock, but they cannot purchase control of the company.

•With a lobster trap strategy, the company passes a provision preventing anyone with more than 10% ownership from converting convertible securities into voting stock. Examples of convertible securities include convertible bonds, convertible preferred stock, and warrants.

In addition to preventing a takeover, there are steps boards can take to thwart a takeover once the process has begun. One of the more common defenses is the adoption of a so-called poison pill. Poison pills can take many forms and refer to anything the target company does to make itself less valuable or less desirable as an acquisition. Some examples include the following:

•A legal challenge. The target company may file suit against the bidder alleging violations of antitrust or securities laws.

•The people pill. High-level managers and other employees threaten that they will all leave the company if it is acquired. This only works if the employees themselves are highly valuable and vital to the company’s success.

•Asset or liability restructuring. With asset restructuring, the target purchases assets that the bidder does not want or that will create antitrust problems, or sells off the assets that the suitor desires to obtain. The so-called crown jewel defense is an example. Sometimes a specific aspect of a company is particularly valuable. A pharmaceutical company might have a highly regarded research and development (R&D) division—a crown jewel. It might respond to a hostile bid by selling off the R&D division to another company, or spinning it off into a separate corporation. Liability restructuring maneuvers include the so-called Macaroni defense—an approach by which a target company issues a large number of bonds with the condition that they must be redeemed at a high price if the company is taken over. Why is it called a Macaroni defense? Because if a company is in danger, the redemption price of the bonds expands like macaroni in a pot. Issuing shares to a friendly third party—the so-called white knight defense—to dilute the bidder’s ownership position is another often-used tactic. In rare cases, a company decides that it would rather go out of business than be acquired, so they intentionally accumulate enough debt to force bankruptcy. This is known as the Jonestown defense.

•Flip-in. This common poison pill is a provision that allows current shareholders to buy more stock at a steep discount in the event of a takeover attempt. The provision is often triggered whenever any one shareholder reaches a certain percentage of total shares (usually 20% to 40%). This dilutes the value of the stock; it also reduces voting power because each share becomes a smaller percentage of the total.

•Greenmail. Greenmail is defined as an action in which the target company repurchases the shares of an unfriendly suitor at a premium over the current market price.

•The Pac-Man Defense. A target company thwarts a takeover by buying stock in the acquiring company, which is launching a takeover.

Despite the seemingly obvious advantages, takeover defenses of all kinds lately have become the target of increasingly potent shareholder activism. The primary shareholder complaints against poison pills are that they entrench management and the board and discourage legitimate tender offers. ISS (now part of RiskMetrics Group), an influential provider of proxy voting and corporate governance services, recommends that institutions vote in favor of shareholder proposals requesting that the company submit its poison pill or any future pills to a shareholder vote, or redeem poison pills already in existence. In addition, a company that has a poison pill in place that has not been approved by shareholders will suffer a significant downgrading in the ISS’s ratings system. Today, about one-third of the S&P’s 500 companies continue to have poison pills.

Shareholder proposals requesting the company to submit its poison pill or any future pills to a shareholder vote, or to terminate an existing poison pill, are not binding on a board—even if overwhelmingly approved by the shareholders. However, if a company fails to implement a proposal approved by the shareholders, there likely will be significant negative consequences for the company and its incumbent directors, including the perception that the company is not responsive to the wishes of its shareholders, substantial withholding of votes in director elections, and downgraded corporate governance ratings.

The Board's Role in Crisis Management5

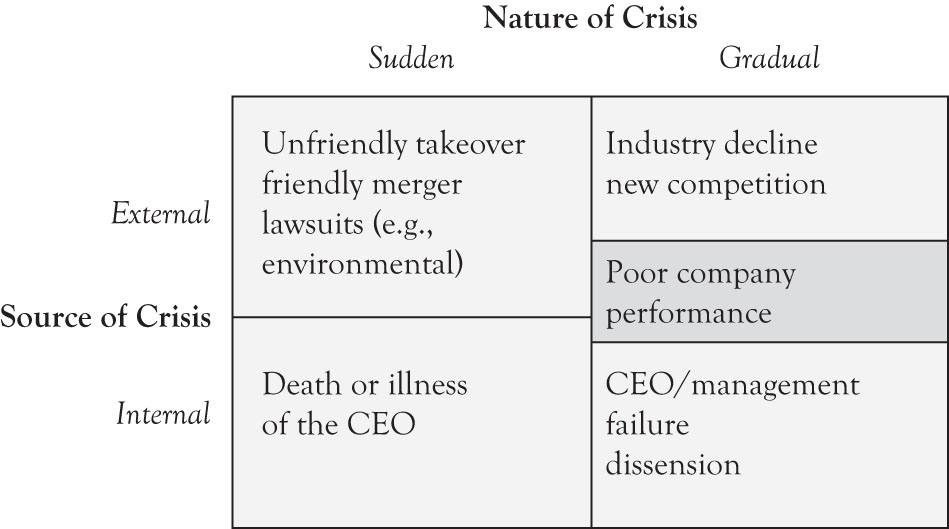

Crises are inevitable. Large corporations can expect to face a crisis on average every 4 to 5 years. Every CEO will probably have to manage at least one crisis during his or her tenure. A director may have to face two or three crises during a normal tour of service on a board. Crises can take many forms—an industrial accident, product tampering, financial improprieties, sexual harassment allegations, or a hostile takeover. Any sudden event that threatens a company’s financial performance, reputation, or its relations with key stakeholders has the potential to become a crisis (Figure 9-2).

Figure 9-2. Corporate crises requiring board engagement.

Some crises are preventable, while others are not. Many are of a company’s own making, resulting from sins of commission or omission. In those cases, the board certainly has a role to play in crisis prevention and has clear accountability for failing to faithfully execute its fiduciary duties. A good many crises begin as problems, developing gradually over time, with plenty of opportunities for an alert board to step in and take corrective action.

Nadler (2004) groups crises into one of four categories:

1.Gradual emergence, external origin. These might involve economic downturns or the emergence of competitive threats, such as breakthrough technologies, new go-to-market strategies, alliances of major competitors, or regulatory changes that limit business practices or expand competition.

2.Gradual emergence, internal origin. Examples range from strategic mistakes (such as a poorly conceived merger) to failed product launches, the loss of key talent to competitors, and employee discrimination suits.

3.Abrupt emergence, external origin. Some of the most obvious examples are natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and product tampering.

4.Abrupt emergence, internal origin. This can include the sudden death or resignation of one or more key executives, failure of critical technology, production, or delivery systems, or the discovery of fraud.

In the event of a gradually emerging crisis, a carefully designed risk management process should provide warnings, in plenty of time, for the company either to avoid the problem entirely or to take corrective action before it develops into a full-blown crisis. Abrupt crises are more problematic; no one can predict a terrorist attack, an earthquake, a plane crash, a shooting spree by a disgruntled employee, or a CEO’s sudden decision to quit and go to work for a competitor. But sound planning can help the company mitigate the consequences and speed up the recovery. The board has an obligation to ensure that management regularly reviews, updates, and practices all aspects of crisis planning.

To deal effectively with any of these scenarios, a board must put together its own crisis management plan, which identifies the different roles it may have to play depending on management’s role in the crisis. The most challenging situation occurs when the CEO is the source of the crisis. This scenario requires identifying what specific role board leaders and individual directors should play, and who the board should call on for independent guidance on legal, financial, or public relations issues.

Thus, the board needs to be absolutely clear about how it will be organized during a crisis, which members have particular expertise it can call upon, and who will take the lead in efforts to restore the confidence of employees, investors, and other stakeholders.

Crises Involving the CEO

During most crises, the board has an important but secondary role to play. That is, ordinarily the CEO is the chief crisis manager and communicator, and the board operates in the background to provide oversight, advice, and support. But, as noted above, when the CEO is the cause of the crisis, the board has no choice but to assume the full burden of safeguarding the interests of the company and its shareholders. That situation can arise for a host of reasons. The most obvious is the CEO’s death or sudden departure.

To determine who should take the lead in the event of a crisis, the board first must decide whether the crisis creates a real or potential conflict between the interests of management and the company. A hostile takeover bid, for example, may threaten the jobs of senior executives but still be in the best interests of shareholders. In such instances, only the board can provide the necessary leadership to maintain stability in the company and retain the confidence of employees, customers, and investors.

Every board should have a detailed plan for dealing with the sudden and unexpected loss of the CEO. Once emergency succession plans for the CEO and other top officers have been developed and agreed on by the board and the CEO, they should be reviewed and updated at least once a year.

Other Crises: The Board's Role in Supporting and Advising the CEO

Most corporate crises are not about the CEO. Usually, therefore, the CEO will act as the chief crisis officer with the board playing a supporting role—approving key decisions, providing the CEO with a confidential sounding board, giving informed advice based on directors’ previous crisis experience or special expertise, and demonstrating confidence in the CEO and support for management’s efforts to navigate the crisis.

In a crisis, boards need two things above all else: information and a credible, candid communications policy that keeps shareholders, the media, and everybody else abreast of what is happening. If necessary, boards should launch an independent investigation of what happened and why, and retain their own outside counsel. Constant communication between the CEO and the board is also critical. The CEO must keep the board informed as events unfold and should engage the board in evaluating alternative courses of action. This provides the CEO with the benefit of the board’s collective experience with crises at other companies.

Key Points to Remember

1.The growth in shareholder activism over the past 10 years has primarily been led by two groups: profit seekers and ideologists. In the first category are private equity groups and other big institutional investors. The second mainly consists of social investors whose investment strategies are geared toward a cause.

2.Although shareholder proxy proposals typically are not binding or may not receive enough votes to pass, they draw public attention to companies’ practices and often force them to reconsider their policies.

3.The most popular shareholder resolutions of the most recent proxy season concern issues such as majority voting, access to the proxy statement, declassifying boards, “entrenchment” devices (classified boards, poison pills, supermajority vote requirements, the right to call special shareholder meetings, among others) and, of course, compensation alignment and disclosure.

4.The emergence of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a more prominent item on a board’s agenda reflects a shift in popular opinion about the role of business in society and the convergence of environmental forces.

5.Corporate takeovers first became a prominent feature of the U.S. business landscape during the 1970s and 1980s. Hostile acquisitions generally involve poorly performing firms in mature industries and occur when the board of directors of the target is opposed to the sale of the company.

6.The management and directors of target firms may resist takeover attempts either to get a higher price for the firm or to protect their own self-interests. The most effective methods are built-in defensive measures that make a company difficult to take over. These methods are collectively referred to as “shark repellents.”

7.A board must formulate a crisis management plan, which identifies the different roles it may have to play depending on management’s role in the crisis. The most challenging situation occurs when the CEO is the source of the crisis.

8.Every board should have a detailed plan for dealing with the sudden and unexpected loss of the CEO.

9.In a crisis, boards need two things above all else: information and a credible, candid communications policy that keeps shareholders, the media, and everybody else abreast of what is happening.