External Mechanisms of Corporate Governance in Spain

4.1 The Market for Corporate Control

The market for corporate control disciplines the managers of corporations with publicly traded stock to act in the best interests of shareholders. By buying up enough shares to vote in a new board of directors, a bidder can then replace a less-talented or unmotivated management team. The bidder profits when the new management team gets results, which can come in the form of improved corporate performance, higher profits, and, ultimately, higher share prices. The importance of the market for corporate control is very different across countries due to a number of historical and institutional factors. As Jensen (1993) states, the failure of the internal mechanisms of corporate control has resulted in a more and more important role of the external mechanisms, among which the market for corporate control plays an outstanding role (Cuervo 2002).

4.1.1 Legal Issues

The control of a Spanish listed company must be acquired by launching a takeover bid. Exceptionally, control gained through a merger may be exempt from the obligation to launch a takeover bid if it can be proved that merger was not carried out to control the target company. The control is supposed to have been acquired when at least 30 percent of the voting rights is reached. For the sake of the equal treatment, the terms of the offer must be the same for all holders of the securities to which the bid is addressed and who are in the same circumstances.

The main consents required to launch a takeover bid in Spain are the resolution of the bidder’s managing body approving the takeover bid, the authorization of the takeover bid from the Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (CNMV), the clearance from antitrust authorities (if required), and when the target company operates in a regulated sector, such as finance, energy, or telecommunications, the authorization from the relevant government agency.

Takeover bids may be mandatory or voluntary, although the boundaries between both types have been greatly blurred in recent laws. Conde (2013) explains that voluntary bids have several important advantages. First, in a voluntary bid the price can be freely determined by the bidder, whereas in a mandatory bid it must be approved by the CNMV. Second, in voluntary bids different types of compensation can be offered (i.e., cash, exchange of securities, or a combination of both), whereas mandatory bids must include a cash compensation. In addition, voluntary bids can be withdrawn more easily than mandatory bids.

From a legal perspective, it is possible to engage in a hostile acquisition in Spain. The difference between hostile and friendly bids (which, incidentally, is not a legal classification) depends on the position of the target company’s board of directors in relation to the takeover bid. If the board of directors support the bid, it shall be considered to be friendly, whereas if the board does not back the bid, it shall be considered hostile.

In Spain, there are no specific rules governing the bidder’s approach to the potential target company. Nevertheless, any agreement between the bidder and the target board must be disclosed in the bid prospectus and also mentioned in the report issued by the target company’s board of directors. In any case, the attitude of the target board is vital for the success of a takeover bid. The board of directors and the management of the target company are prevented from taking any action that may frustrate or disrupt the success of a takeover bid, so as to ensure that the interests of shareholders prevail over their own interests. In spite of that, they can keep a critical ability to beat the bidder by searching for a competing offer or engaging in transactions aimed at causing the bid to fail, provided the general shareholders’ meeting approves any such transactions.

In addition, once the takeover bid has been authorized by the CNMV, the target company’s board must issue a report on the bid, which should state their position toward the bid. This statement can influence the decision taken by the target company shareholders.

The employees of the target company and the bidder are entitled to be informed of the bid as soon as it has been announced, and to receive the prospectus of the bid, once authorized by the CNMV. The prospectus must include extensive information on the bidder’s corporate organization, ownership structure, activity, and financial situation, including net worth, turnover, total assets, financial liabilities and results, and information about the bidder’s plans in relation to the target company’s employment policy. The target company’s employees shall also be provided with the report on the bid issued by the target company’s board of directors. This report must include a discussion on the possible consequences of the bid and the plans of the bidder over the target company’s employment.

According to Conde (2013), confidential negotiations between the bidder, the target company, or the target’s main shareholders are allowed. However, special attention should be paid to the quotation of the target company shares and to the news relating to the company during the negotiation process. If any unusual development of the trading volume or the listing price of the target company is detected, or if there are any leaks about the negotiations, the bidder must immediately make public its intention to launch a takeover bid.

Although the bidder can purchase shares of the target company outside of the bidding process, these purchases in a listed company must be publicly disclosed when they result in the relevant shareholding reaching, or being reduced to 3 percent, 5 percent, and successive multiples of 5 percent up to 50, 60, 70, 75, 80, and 90 percent of the company share capital.

Broadly speaking, protectionism does not operate in favor of local owners. But in the sectors related to national defense, where investment from foreign buyers can be constrained on the basis of public interest, Spanish rules apply equally to both national and foreign buyers. This means that neither the Spanish Government nor the regulatory agencies have a protectionist attitude to foreign investments.

There is no standard duration for a takeover bid process, given that it depends on a number of factors. Nevertheless, a plain and simple takeover bid could take between 90 and 120 days to be completed from the time it is filed with the CNMV. The announcement of an intention to offer should be made as soon as the decision has been made by the bidder. In the case of mandatory offers, the announcement of the offer should be made without delay following the acquisition of control. Within one month of announcement, the bidder must submit a request for authorization to the CNMV. Once the CNMV receives the offer document and other complementary information, it must decide within seven business days whether the offer documentation satisfies the minimum requirements to be reviewed by the CNMV. If it does, the CNMV will authorize or reject the offer within 20 business days of filing. Within five business days of CNMV authorization, once the offer is authorized by the CNMV, the bidder must announce the terms of the offer, describing all of its essential features. In its announcement, the bidder must specify the applicable acceptance period, which must be no less than 15 calendar days and no more than 70 calendar days from the date of publication of the announcement.

Within 10 calendar days of the start of the acceptance period, the target company’s management must issue a detailed and reasoned report responding to the offer. Within five business days from the end of the acceptance period, the Spanish stock exchange authorities communicate the total number of shares tendered into the offer in each exchange. Within two business days of receipt of the results, the CNMV aggregates and communicates the final results of the offer to the bidder, the target company, and the stock exchange authorities. On the third business day following announcement of the results, the offer consideration is settled in accordance with the rules of the Spanish clearance and settlement system. The CNMV will release the bank guarantee or cash deposit provided by the bidder in respect of any cash consideration only once the offer has been settled in full.

As far as the factors most likely to influence the outcome of the acquisition process are concerned, the consideration offered by the bidder is obviously the most critical one. Other important influences on the success of a bid are the need to obtain sector-related administrative approvals, the existence of competing bids and the defensive measures lawfully adopted by the target company.

4.1.2 Stylized Facts

Relative to its Anglo-Saxon counterparts, the Spanish market for corporate control is not so active and so big as in other countries. In Spain, as a bank-oriented country, the market for corporate control does not play such outstanding role as in other countries due to two main reasons: the size of the capital markets and the corporate ownership structure.

First, capital markets are not an outstanding source of funds for firms; they are less developed than in other countries. The low number of listed companies, along with the relative illiquidity of the market reduces the informativeness of stock prices and decreases significantly the possibility of success of hostile takeovers. As shown in Figure 4.1, the number of quoted domestic firms in Spain is not only lower than in the Anglo-Saxon countries such as the United Kingdom or the United States but also lower than its continental comparable counterparts such as Germany or Italy.

Figure 4.1 Number of listed firms

Sources: World Federation of Exchanges (www.world-exchanges.org/); World Bank (www.worldbank.org/); and Bolsas y Mercados Españoles (www.bolsasymercados.es/ing/home.htm).

Notes: Listed domestic companies are the domestically incorporated companies listed on the country’s stock exchanges at the end of the year. The number of listed companies does not include investment companies, mutual funds, or other collective investment vehicles.

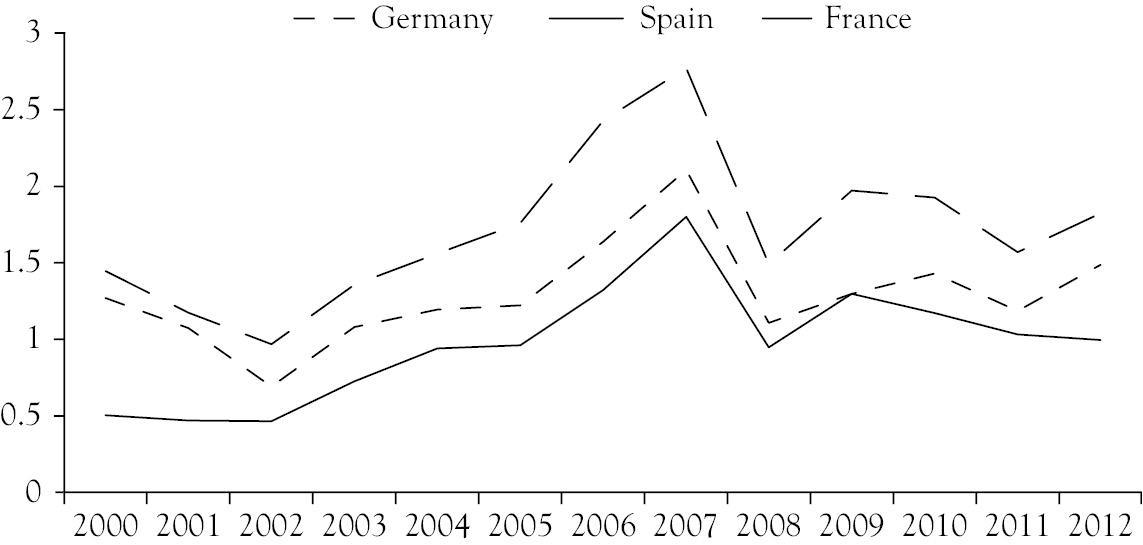

In terms of market capitalization, although the Spanish capital markets follow a similar pattern to the French or German one, the market capitalization is also lower than these markets. As shown in Figure 4.2, in the first years of the 21st century the economic growth fueled the increase in the market capitalization of the euro area until reaching a peak in 2007. Nevertheless, the financial meltdown has meant a decrease of the market capitalization across Europe, resulting in Spanish capital markets having lower figures.

Figure 4.2 Market capitalization

Source: World Bank.

Note: Total capitalization of equity markets in Germany, Spain, and France.

Data in billions of U.S. dollars.

It should be highlighted that capitalization is concentrated in a relatively low number of companies. The two largest companies accounted for 29.4 percent of total capitalization of the Spanish market in 2012 and the 13 largest companies accounted for over 75 percent.

In Table 4.1, we compare the size of the Spanish market (measured in relation to the size of the national economy) with some of the major international markets. It can be seen that the ratio between capitalization and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Spain rose slightly in 2012. However, this ratio, which has suffered since the start of the crisis due to the sharp fall in prices in the Spanish market, remains low compared with the major international markets.

Table 4.1 Market capitalization as a percentage of nominal GDP

|

|

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

USA1 |

104.4 |

118.2 |

103.7 |

119.0 |

|

New York |

82 |

91.5 |

78.2 |

89.8 |

|

Japan2 |

67.3 |

71 |

57.2 |

66.9 |

|

London3 |

104.3 |

84.1 |

87.2 |

91.6 |

|

Euronext4 |

63.9 |

75 |

60.0 |

67.7 |

|

Germany |

35.1 |

43.2 |

35.2 |

42.6 |

|

Spain |

52.3 |

44.5 |

39.6 |

41.7 |

1 The numerator is the combined total of the NYSE and Nasdaq.

2 Includes data from the Tokyo and Osaka stock exchanges.

3 The London data as from 2010 includes data from the Borsa Italiana, integrated in the London SE Group, and the GDP of both countries, after converting the Italian data to sterling pounds.

4 The denominator is the sum of the nominal GDP of France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Portugal.

Source: World Federation of Exchanges (www.world-exchanges.org/); International Monetary Fund (www.imf.org/); and CNMV (https://www.cnmv.es/).

Despite the relatively low capitalization, the picture that emerges from the analysis of liquidity in Spanish markets is different. As shown in Table 4.2, the ratio based on trading stands at an average level compared with other internationally relevant markets although the significant fall suffered over the last year.

Table 4.2 Market trading as a percentage of nominal GDP

|

Country |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

USA1 |

212.3 |

208.2 |

204.0 |

148.1 |

|

New York |

123.1 |

121.6 |

119.6 |

85.7 |

|

Japan2 |

81.2 |

70.2 |

69.6 |

60.8 |

|

London3 |

126.9 |

63.8 |

70.0 |

60.4 |

|

Euronext4 |

43.9 |

50.3 |

48.4 |

38.5 |

|

Germany |

61 |

49.2 |

48.3 |

37.3 |

|

Spain |

83.4 |

97 |

86.3 |

65.8 |

1 The numerator is the combined total of the NYSE and Nasdaq.

2 Includes data from the Tokyo and Osaka stock exchanges.

3 The London data as from 2010 includes data from the Borsa Italiana, integrated in the London SE Group, and the GDP of both countries, after converting the Italian data to sterling pounds.

4 The denominator is the sum of the nominal GDP of France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Portugal.

Sources: World Federation of Exchanges (www.world-exchanges.org/); International Monetary Fund (www.imf.org/); and CNMV (2011).

In spite of this drop, the Spanish stock market was the fifth largest European market in terms of trading, after the Chi-X multilateral trading facility, the London Stock Exchange, NYSE Euronext, and the German Stock Exchange.

Analogous to the capitalization, the stock market trading is highly concentrated in a relatively low number of securities too. In 2012, the six most liquid securities in the market (BSCH, Telefónica, BBVA, Repsol, Inditex, and Iberdrola) accounted for over 75 percent of trading.

The second factor underlying the relatively lower development of the market for corporate control in Spain is related to the corporate ownership structure. As shown in the third section, Spanish quoted companies usually have a concentrated ownership structure with a group of blockholders or controlling shareholders.

This ownership structure goes hand in hand with some control-enhancing mechanisms as means to increase the control power of the main shareholders. In 2007, the Institutional Shareholders Services conducted a survey among 16 European countries on the proportionality between ownership and control in European Union listed companies. The study analyzes a list of control-enhancing mechanisms, which do not follow the proportionality principle. Some of these mechanisms are used to allow existing blockholders to enhance control by leveraging voting power (diversions related to the one share, one vote principle and pyramid structures), other mechanisms can function as devices to lock-in control (priority shares, depository certificates, voting rights ceilings, ownership ceilings, and supermajority provisions), and other mechanisms are represented by coordination devices such as shareholders agreements.

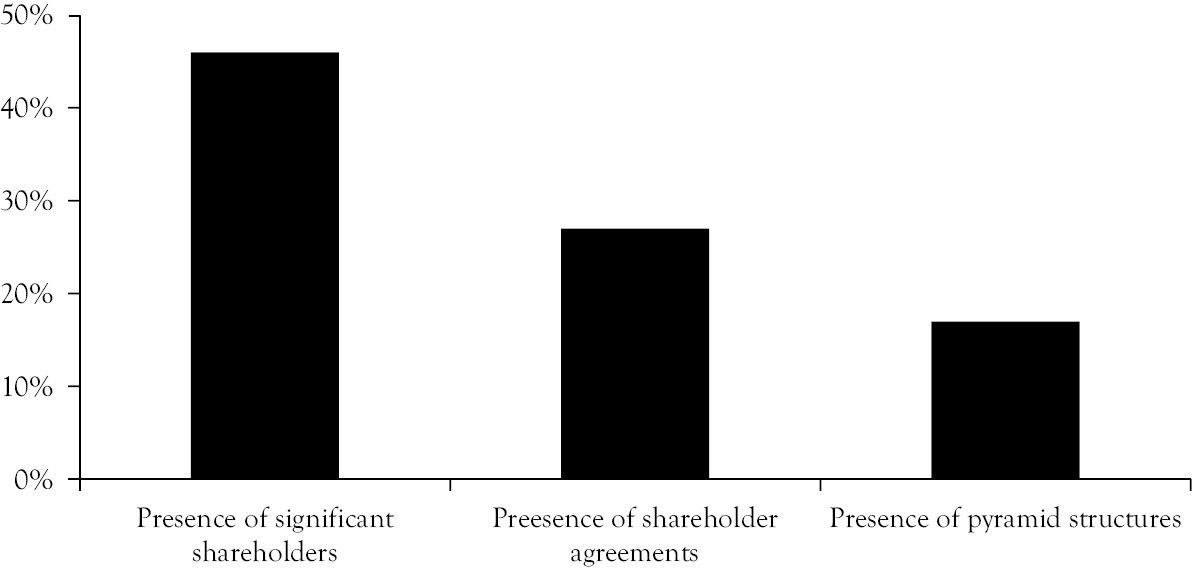

According to this study, 62 percent of the Spanish surveyed firms had a control-enhancing mechanism. Furthermore, whereas 49 percent of the firms feature a single mechanism, 13 percent of the surveyed firms feature at least two mechanisms. The pyramidal structures and the coalitions of shareholders are the most often used mechanisms. As displayed in Figure 4.3, this survey shows that 45 percent of the companies have at least one significant shareholder who owns more than 20 percent of shares, and 17 percent of listed firms feature a pyramid structure.

Figure 4.3 Control-enhancing mechanisms among Spanish firms

Sources: Institutional Shareholder Services (2007) and Santana Martín (2010).

Consistent with these data, Santana Martín (2010) reports that around 27 percent of quoted companies feature a coalition of shareholders. Coalitions of shareholders are defined by the Transparency Law (2003) as those agreements affecting the exercise of voting rights at general meetings, or that which constrain the free transfer of shares and bonds of listed companies. Likewise, The Royal Decree 1362/2007 defines acting in concert as an agreement whereby the parties use their voting rights to impose a common policy in connection with the company’s management or to significantly influence its course.

Agreements can be grouped into four main categories: vote pooling and limitations on the free transfer of shares; vote pooling; limitations on the free transfer of shares; and composition of the board of directors or some other governing body, and setting of dividend policy. In Figure 4.4, we report the proportion of each category on the whole list of coalitions.

Figure 4.4 Types of shareholder coalitions

Source: CNMV (2011).

These agreements account for more than 45 percent of voting shares. As shown in Table 4.3, although the proportion of voting rights implied in the coalition is quite steady, there is an increasing trend in the proportion of firms with such kind of mechanisms: In 2003 only 15 percent of the firms featured a shareholder coalition, whereas in 2011 this proportion has almost doubled up to 28 percent.

Table 4.3 Shareholder coalitions in Spanish firms

|

|

2003 |

2005 |

2007 |

2009 |

2011 |

|

% Firms with coalitions |

15.85 |

20.00 |

30.36 |

23.67 |

28.42 |

|

% Voting rights in the coalition |

44.96 |

41.09 |

46.89 |

42.65 |

45.85 |

Source: Santana Martín (2010).

The use of shareholder coalitions is significantly different from the voting agreements in the U.S. market or the analysis of the divergence between control rights and cash flow rights in a number of ways. First, these agreements are more transparent given the publicity requirements imposed by the CNMV. Second, the dominant owners who have effective control of the company take the lead in the shareholder agreements. These agreements do not require the transfer of shares to an involved shareholder but rather implies an explicit commitment that coalition members will vote with the dominant owner or will limit the transfer of shares outside the coalition. Third, coalitions improve the stability of the ownership structure because they are often signed for a period not shorter than two years and can be rolled over. Four, the coalitions do not generate an internal market among the divisions of the same firm as the pyramid structures do. In addition, the Spanish law, by requiring the identification of the members, allows knowing the composition of the controlling group in actual terms and not in terms of likelihood (i.e., the group of shareholders most likely to form a coalition) as some of previous research does.

Although there is a widespread use of shareholder coalitions in many countries, Spain provides a unique opportunity for this analysis because since 2003 listed firms must report certain information on shareholder coalitions. The Improvement of the Transparency in Quoted Firms Law 26/2003 explicitly allows the agreements among shareholders that modify the voting rights in the general shareholders meeting or that constraint the transmissibility of shares. In so doing, the shareholders voluntarily accept to limit their votes or their ability to sell the shares. These agreements must be published in the corporate website and also must be notified to the CNMV. This announcement must show who the shareholders involved in the agreement are, the proportion of shares involved, and the content of the agreement (i.e., limitation of votes or limitation of shares sales).

Shareholder coalitions can play a dual role. On the one hand, control-enhancing shareholder coalitions have a beneficial effect on minority shareholders’ wealth by improving significant shareholders’ ability and incentives for managerial control and on the other, they enable a balanced power among the dominant owner and other large shareholders. This control-enhancing role is more important in countries with less liquid capital markets and where legal and political factors constrain the market for corporate control. In addition, coalitions can also be an efficient control mechanism in countries such as Spain with weak legal protection of minority shareholder by enhancing the contest to the power of other large shareholders against the dominant owner’s control.

On the contrary, self-dealing shareholder coalitions empower the dominant owners to such an extent that they can become entrenched and can extract private benefits at the expense of nonparticipating shareholders. In this scenario, coalitions may exacerbate the conflicts of interest among shareholders by conferring too much power to a few entrenched owners. Furthermore, in some legal environments of high ownership concentration, dominant owners are usually linked to managers by family, business, or other kinds of group ties. Hence, the entrenchment of shareholders can mean, to some extent, the entrenchment of managers.

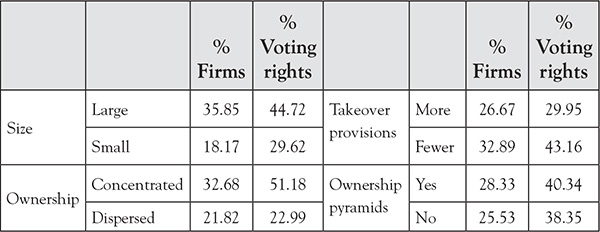

The thorough analysis of Santana Martín (2010) provides certain insights into some characteristics of the shareholder coalitions among Spanish firms. More specifically, this author shows significant differences among firms in terms of size, ownership concentration, anti-takeover provisions, and the pyramid structure.

As shown in Table 4.4, large firms feature shareholder coalitions almost twice as often as small quoted firms (35 percent vs. 18 percent) and the proportion of involved voting rights is significantly higher. The firms with concentrated ownership also have more coalitions than their dispersed ownership counterparts and, more importantly, the difference in the proportion of voting rights is even higher than in the previous case. Given the possible conflicts of interests between dominant shareholders and minority shareholders, the data from Table 4.4 can mean that large shareholders in the firms with concentrated ownership use the coalitions as an enhancing mechanism in order to increase their power and become entrenched.

Table 4.4 Shareholder coalitions and firm characteristics

Source: Santana (2010).

The comparison of the firms with anti-takeover provisions provides interesting insights too. We can see that firms with defensive measure against takeovers feature less coalitions than their counterparts. It could mean that shareholder coalitions are an alternative protection measure, so that they become more necessary when the firms have fewer provisions.

In the same vein, firms have different attitude toward shareholder coalitions depending on the pyramid structures. We must keep in mind that these structures are control-enhancing mechanisms that allow the separation between voting rights and cash flow rights through a number of intermediate firms. As shown in Table 4.4, shareholder coalitions are more frequent in firms with pyramid structures. As far as the family nature of the firm is concerned, family firms do not use the shareholder coalitions differently from the nonfamily firms.

As far as anti-takeover provisions are concerned, Santana and Aguiar (2007) and Ruiz and Santana (2009) provides an exhaustive survey of this instrument in the Spanish quoted firms. They thoroughly analyze the corporate by-laws of all the listed firms and define the five provisions summarized in Table 4.5.

Table 4.5 Anti-takeover measures in Spanish corporate by-laws

|

Voting right ceilings |

Restriction to the voting rights held by a single shareholder (usually 10%). |

|

Supermajority votes |

A level of approval for specified actions higher than the minimum set by the Spanish general law. Such provisions often establish approval levels of 75% or 90% for actions that otherwise would require simple majority approval (mergers and acquisitions, stock issuance, and others). |

|

Seniority of directors |

Need to have been shareholder for a certain time to be elected as director. |

|

CEO seniority |

Need to have been director for a certain time to be elected as chairman of the board. |

|

Staggered boards of directors |

Boards in which directors are divided into separate classes and elected to overlapping terms. |

Source: Santana and Aguiar (2007).

These provisions can be considered as internal control provisions because they increase a large shareholder’s cost of exercising control or influencing corporate policies, which therefore directly affect the internal market for control. By imposing costs on large shareholders, however, these mechanisms also can impede external bids for control.

Based on these provisions, Santana and Aguiar (2007) compute an index of takeover protection. This index is defined as the sum of five dummy variables, each one equaling one whether the corporate by-laws allow each one of the provisions. Thus, the index of takeover protection oscillates between zero and five. The higher the index, the more entrenched the managers against possible takeovers.

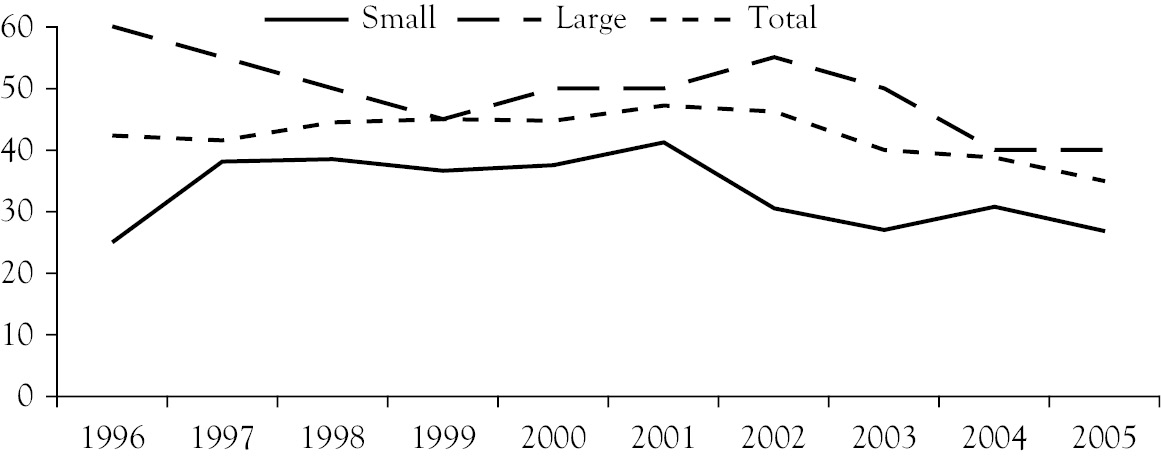

As shown in Figure 4.5, the proportion of Spanish firms with anti-takeover provisions in their corporate by-laws has declined slightly in recent years. In 1996, 42.3 percent of firms had anti-takeover provisions, whereas in 2005 (the latest year with available information), it amounted to 34.9 percent. More importantly, there has been a clear reduction in the number of firms with provisions since 2003, which can be attributed to the enactment of the Improvement of the Transparency in Quoted Firms Law 26/2003. There are also some differences due to the size of the firm because larger firms usually have more provisions than their smaller counterparts.

Figure 4.5 Percentage of firms with anti-takeover provisions

Source: Santana and Aguiar (2007).

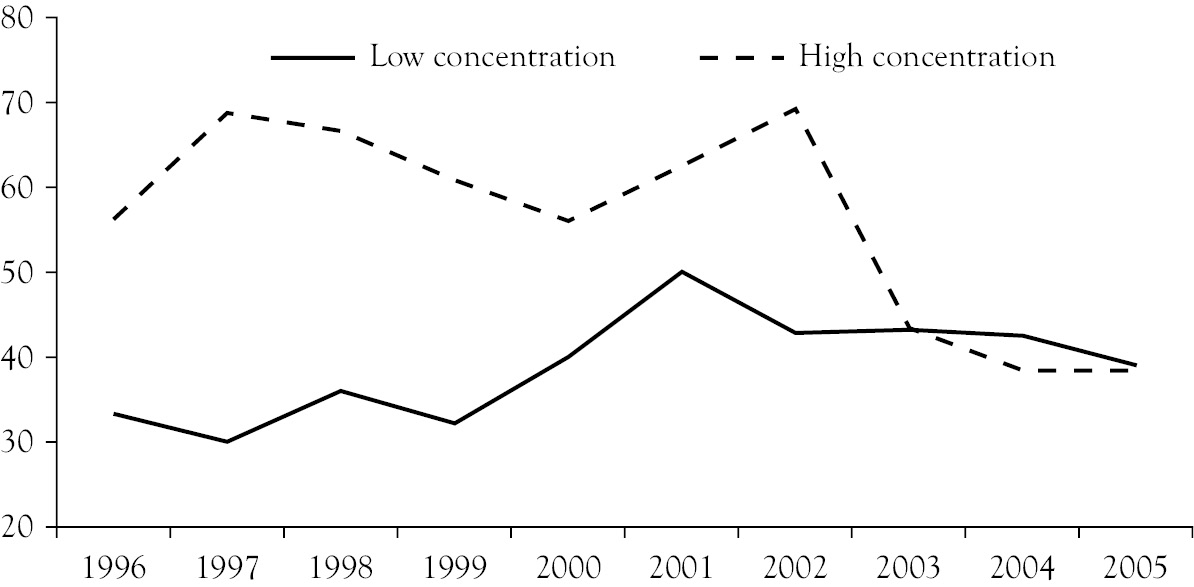

Figure 4.6 shows that the proportion of firms with defensive measures depends also on the ownership concentration. Whereas firms with high-concentrated ownership used to have more provisions, the recent trend in capital markets has resulted in a convergence process, so that there are no significant differences between both kinds of firms after 2003.

Figure 4.6 Ownership concentration and anti-takeover provisions

Source: Santana and Aguiar (2007).

Percentage of firms with anti-takeover provisions depending on the ownership structure. Low (high) concentration firms are those in which the voting rights of the largest shareholder are below 20 (over 50) percent.

The takeover protection index follows a similar pattern (Figure 4.7). The number of defensive measures has not only decreased during the 1995–2005 period but also experienced a sharp decline after 2003 due to the improvement in the information requirements in the Spanish capital markets. Regarding the effect of the firm size, there is a clear convergence between large and small firms.

Figure 4.7 Evolution of the index of takeover protection

Source: Santana and Aguiar (2007).

Notes: Average number of anti-takeover provisions depending on the ownership structure. Low (high) concentration firms are those in which the voting rights of the largest shareholder are below 20 (over 50) percent.

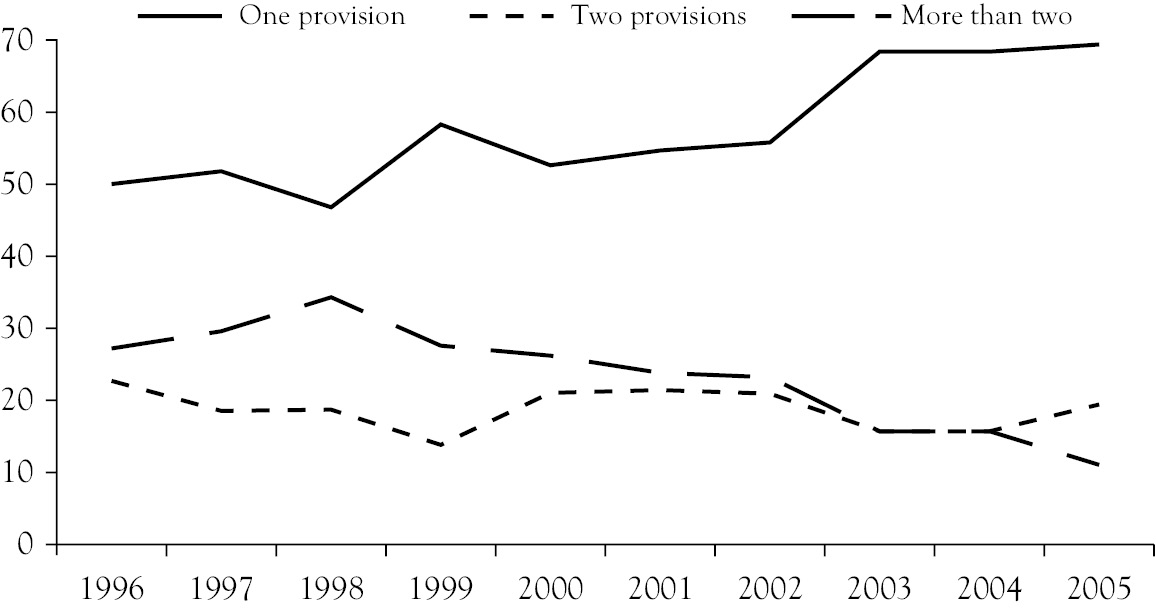

In Figure 4.8, we show the distribution of the protection index. We report the proportion of firms with anti-takeover measures depending on the number of provisions in their by-laws. One must take into account that these proportions are calculated only on the firms that actually have protective measures. The percentage of firms with a single measure increased from 50 percent in 1995 to 69.4 percent in 2005. On the contrary, the proportion of firms with three or more provisions decreased from 27.2 percent to 11 percent in the same period. The proportion of firms with two protective provisions in their by-laws remained steady around 20 percent.

Figure 4.8 Distribution of the index of takeover protection

Source: Santana and Aguiar (2007).

Note: Number of anti-takeover measures in the corporate by-laws (in percentage).

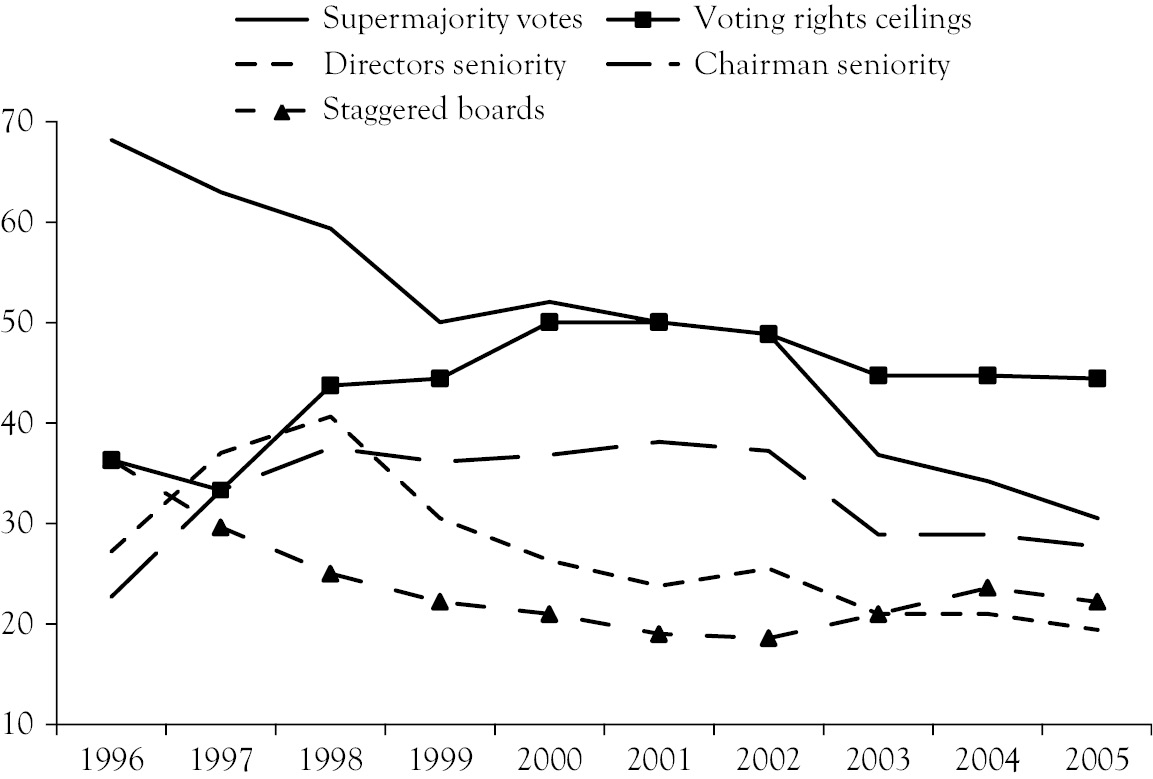

As far as the types of provisions actually implemented are concerned, Figure 4.9 shows that the voting rights ceilings are the most usual measure with 44 percent of the companies using this provision. The second most usual provision is supermajority votes, although there has been a decline in the proportion of firms with this measure in their corporate by-laws: In 1996, 68.1 percent of the companies that had protective measures used this provision, whereas in 2005, the proportion had fallen to 30.5 percent. Once again, we can see that 2003 is an inflexion point and the proportion of provisions decreases after 2003.

Figure 4.9 Anti-takeover provisions actually implemented

Source: Santana and Aguiar (2007).

Note: Percentage of firms with each anti-takeover provision.

Given these characteristics of the Spanish capital markets (both the low size of the market and the specific measures adopted by the firms) it comes with little surprise the low activity of the market for corporate control. In Figure 4.10, we report the number and the value of takeovers among listed firms. This figure suggests two conclusions. First, the low number of takeovers related to the whole population of listed firms. Second, in spite of this low number, there is a steady declining trend in the number of operations. As far as the amount is concerned, with the exception of the 2006 to 2007,1 there has not been such a declining trend as in the number of takeovers.

Figure 4.10 Takeovers among listed firms

Source: CNMV (2011).

Figure 4.11 provides additional information about the number and the value of announced mergers and acquisitions with Spanish participation (both among quoted and nonquoted firms). Contrary to the situation of their listed counterparts, the market for mergers and acquisition among nonlisted firms has been more active in the latest 10 years than it used to be during the 1990s decade. In any case, the mergers and acquisitions involving Sp firms is significantly lower than in most of the countries of Western Europe.

Figure 4.11 Number and value of announced mergers and acquisitions

Source: Institute of Mergers (www.imaa-institute.org) and Acquisitions and Alliances.

4.2 External Audit

The market for audit services in Spain started with the implementation of the 8th Directive on Company Law (García and Argilés, 2013). With the main goal of increasing the reliability of the company’s financial statements, the Spanish Audit Law was enforced in 1988. This law established the obligation for companies above a certain size to appoint an external auditor to issue a report about the company’s financial statements.

To safeguard auditor independence, the Spanish Audit Law established a set of criteria to regulate the auditor–client relationship. Accordingly, a multiyear contract was established with a length ranging between three and nine years. In addition, irrespective of the length of the initial contract, the reelection of the audit firm was not allowed. The imposition of a limit in the number of years a company could be audited by the same firm was equivalent to establish a mandatory auditor rotation rule. Nevertheless, both the limit on the maximum number of years to be audited by the same firm, and the prohibition to renew the audit contract were abolished after a legal reform in 1995.

After more than 20 years, the Spanish Audit Law has been updated and modified with a new Audit Law (12/2010). This new legal framework has aimed to strengthen the reliability of auditing and promote a homogenous environment in Europe. The new law adapts the Spanish Audit Law to the changes that have taken place in Spanish corporate–commercial and accounting law in recent years. It also amends the liability system for auditors, who must assume full liability in relation to consolidated financial statements or accounting documents, meaning that their liability cannot be restricted to the group companies that had been audited by them.

The new law specifies the system of legal sources that must be used in performing the audit, which will be audit standards, ethical rules, and the rules governing the internal quality assurance system of auditors and audit firms. With respect to audit standards, it introduces the international audit standards that will be adopted by the European Commission, and keeps the Spanish audit standards in force until those international standards are adopted.

A characteristic of the new law is that it reduces the public disclosure period for audit standards before they are published by the Accounting and Audit Institute from six to two months. Audits can be performed by persons authorized in another EU member state and by auditors from other countries who are registered. The registration in the Official Auditors’ Register is compulsory for auditors and audit firms who issue auditor’s reports in relation to the financial statements of certain companies domiciled outside the EU, whose shares are admitted for trading in Spain.

Auditors must observe the duties of independence and secrecy in performing audits. The audit regulations clarify the set of actions that must be performed by auditors in the observance of their duty of independence, and delimit the causes that lead to incompatibility for them. The duty of secrecy extends to anyone taking part in the performance of audits. Auditors must be and appear to be independent from the companies they audit in the performance of their functions. Thus, they must refrain from acting when their objectivity in relation to the review of accounting documents could be jeopardized. Independence will be understood as the absence of interests or influences that may undermine the auditor’s objectivity. To assess a possible lack of independence, the performance of other services to the audited company that may limit the auditor’s objectivity must be taken into account. However, with the exception of services consisting of accounting activities, the rest of the services, such as consulting or tax advice, would not imply, in principle, the auditor’s incompatibility.

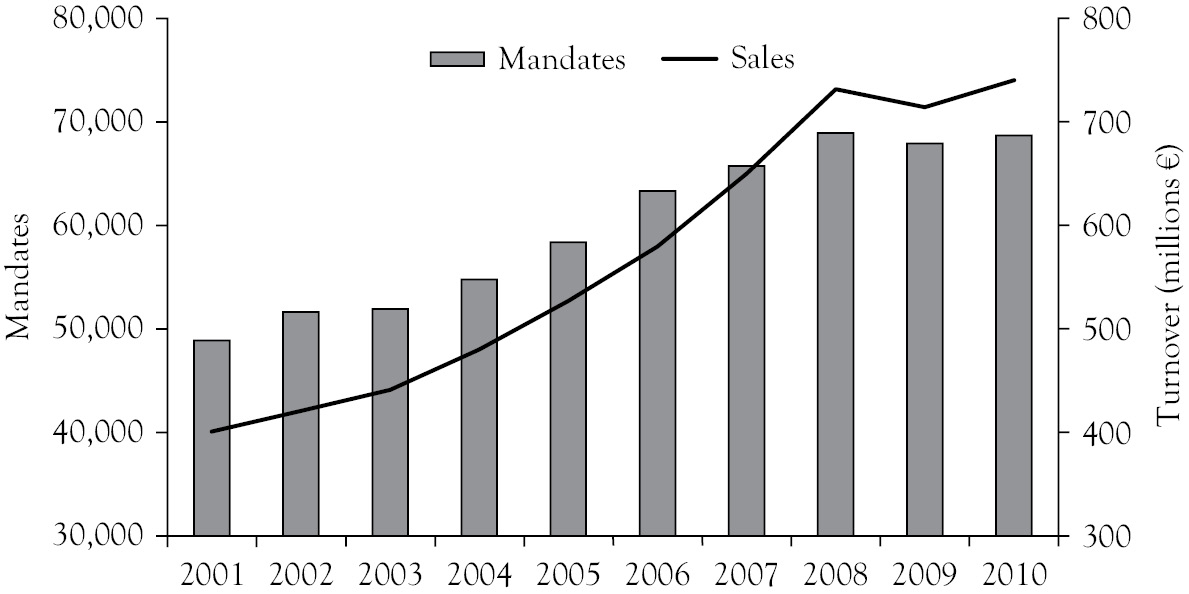

As a consequence of a clearer and clearer legal framework, the audit services have expanded in Spain in recent years (Figure 4.12).

Figure 4.12 Audit services

Source: Crespo (2012).

As in many other countries, the audit market of publicly traded companies is highly concentrated in a situation characterized by the oligopoly of the so-called Big Four audit firms (KPMG, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Deloitte, and Ernst & Young). Although this situation seems to be widely spread across Europe, Spain is one of the countries with a more concentrated audit market (Table 4.6).

Table 4.6 Concentration of the audit market

|

Member state |

Number of companies |

CR1 (%) |

CR4 (%) |

CR8 (%) |

HHI |

|

Austria |

75 |

36 |

83 |

99 |

2,281 |

|

Belgium |

151 |

32 |

88 |

100 |

2,256 |

|

Bulgaria |

218 |

18 |

50 |

76 |

873 |

|

Cyprus |

112 |

32 |

94 |

98 |

2,737 |

|

Denmark |

167 |

53 |

96 |

100 |

3,493 |

|

France |

761 |

24 |

81 |

97 |

1,831 |

|

Germany |

781 |

40 |

97 |

98 |

3,244 |

|

Ireland |

40 |

40 |

98 |

100 |

2,995 |

|

Italy |

269 |

40 |

98 |

100 |

2,786 |

|

Netherlands |

135 |

34 |

91 |

100 |

2,353 |

|

Spain |

155 |

58 |

99 |

100 |

4,050 |

|

Sweden |

391 |

48 |

99 |

100 |

3,437 |

|

United Kingdom |

2061 |

43 |

98 |

100 |

2,884 |

|

EU average |

391 |

38 |

90 |

98 |

2,709 |

Source: Le Vourc’h and Morand (2011).

Notes: Market share by the largest, two largest and four largest audit firms, and the Hirschman-Herfindahl index (HHI) of concentration. The HHI is one of the most often used indexes to measure concentration. It is based on the total number and size distribution of firms. It ranges from 1/N to 1, with N the total number of firms in the market. For a more convenient reading HHI can be computed on a base of 10,000. The United States Antitrust Division Merger Guidelines provide the following classification: not concentrated markets (HHI below 1,500), moderately concentrated markets (HHI between 1,500 and 2,500), and highly concentrated markets (HHI above 2,500).

In fact, in November 2011, the European Commission issued the proposal for a regulation on the quality of audits of public-interest entities and for a directive to enhance the single market for statutory audits. These new rules are a consequence of the financial crisis that has highlighted weaknesses in the statutory audit, especially with regard to banks and financial institutions. Concerns around conflicts of interest have been expressed as well as the potential for an accumulation of systemic risk as the market is effectively dominated by the Big Four companies.

The proposals regarding the statutory audit of public-interest entities, such as banks, insurance companies, and listed companies, envisage measures to enhance auditor independence and to make the statutory audit market more dynamic. One of the key measures in this respect is a mandatory rotation of audit firms, so that audit firms will be required to rotate after a maximum engagement period of six years. Joint audits are not made obligatory but are encouraged. Audit firms will be prohibited from providing nonaudit services to their audit clients. In addition, large audit firms will be obliged to separate audit activities from nonaudit activities in order to avoid all risks of conflict of interest. Enabling auditors to exercise their profession across Europe, the Commission proposes the creation of a Single Market for statutory audits by introducing a European passport for the audit profession. To this end, the Commission proposals will allow audit firms to provide services across the EU and to require all statutory auditors and audit firms to comply with international auditing standards when carrying out statutory audits.

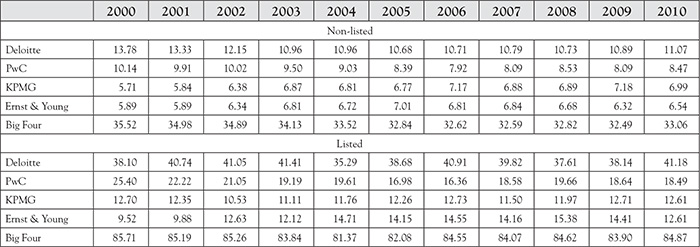

As previously stated, Spain is not an exception in the landscape of audit concentration (Monterrey and Sánchez, 2008; Ruiz Barbadillo et al., 2009). Table 4.7 reports the market share of the Big Four both for nonlisted and listed audit firms. There is a big imbalance between the audit market of nonlisted and listed firms. As it can be seen, the market for nonlisted firms (namely, small and medium enterprises) is much more diversified than the audit market of the quoted firms (basically, large firms).

Table 4.7 Market share (in %) of the Big Four audit firms

Source: Crespo (2012).

To provide a more simple idea of the concentration of the audit market, Figure 4.13 reports the market share of the Big Four in 2010, and Table 4.8 reports the turnover of the 10 largest audit firms in 2009. Once again, we can see the gap between the four largest firms and the following ones.

Figure 4.13 Big Four market share

Source: Crespo (2012).

Table 4.8 Distribution of the audit market

|

Firm |

Turnover |

Firm |

Turnover |

|

Deloitte |

437 |

Grant Thornton |

58 |

|

PwC |

410 |

Praxity |

33 |

|

KPMG |

307 |

Mazars |

33 |

|

Ernst & Young |

278 |

Horwath |

28 |

|

BDO |

86 |

Moore Stephens |

24 |

Source: Le Vourc’h and Morand (2011).

Note: 2009 revenues of the top 10 audit firms (millions €)

To corroborate the concentration of the audit market in Spain, Table 4.9 provides a comparison of the concentration index of n degree between 2001 and 2010. This concentration index measures the market share accrued to the n largest audit firms. Consistent with previous information, there is a clear gap between the Big Four and the other firms. In addition, in dynamic terms, the concentration on the Big Four has not changed significantly in these 10 years, and they still account for approximately 85 percent of the market of large firms.

Table 4.9 Concentration index (in %) in the audit market

|

|

2001 |

2010 |

|

C1 |

38.10 |

41.18 |

|

C2 |

63.50 |

59.67 |

|

C3 |

76.20 |

72.28 |

|

C4 |

85.72 |

84.89 |

|

C5 |

87.52 |

86.59 |

|

C6 |

89.22 |

88.29 |

|

C7 |

90.52 |

89.29 |

|

C8 |

91.02 |

90.29 |

|

C9 |

91.32 |

90.89 |

|

C10 |

91.72 |

91.39 |

|

C20 |

93.3 |

93.4 |

|

C50 |

96.4 |

96.5 |

|

C100 |

98.1 |

97.9 |

Source: Crespo (2012) and Le Vourc’h and Morand (2011).

1 In these years, two significant Spanish firms (Altadis and Endesa) were taken over by foreign companies (Enel Energy and Imperial Tobacco).