Aligning HR Processes with AI—Productivity Measurement and Performance Appraisal

Productivity

How to measure productivity and do an appraisal of employee performance? Align all the HR processes with an AI seamless approach, and you will achieve these twin goals. In this chapter, we will look at gathering productivity information and how we best use the performance appraisal tool as a catalyst for productivity, innovation, and change. We will also explore its motivational ability.

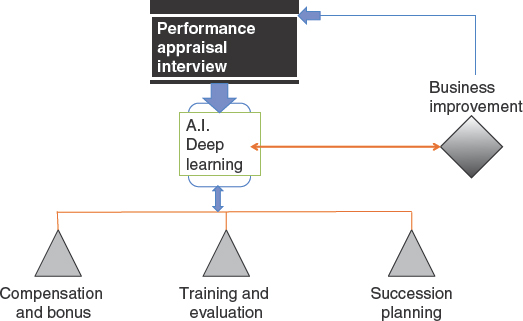

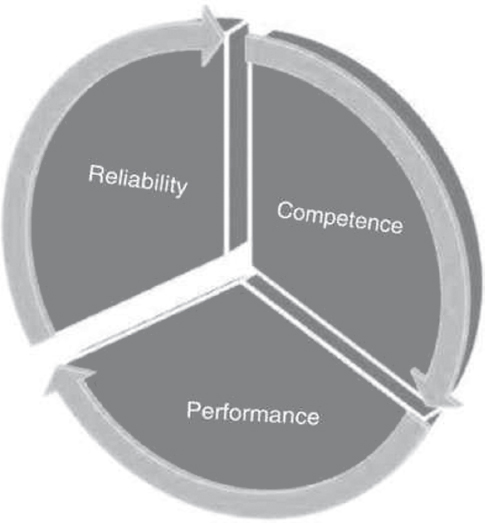

To look at AI and productivity, we must first understand the three components that make up productivity and how to best use them to our advantage (Figure 4.1). AI needs to link and improve them all, productivity being the first. (Davenport and Ronanki 2018)

Figure 4.1 AI and performance appraisal systems

Figure 4.2 Processes that add to organizational efficiency

Sustainable productivity = Competence + Performance + Reliability

Understanding the Ingredients (Figure 4.2)—Competency How to Measure It

The topic of accurately measuring and valuing competencies has eluded both line managers and HR personnel for years. The numerous books to explain competency frameworks have done nothing but to add complexity and confusion to what is a straightforward concept.

What are the competencies and how are they structured?

The concept of having a competency framework was to enable organizations to benefit from a uniform approach. Competencies are a key observable behavior. They are critical words in that short statement—the first is key when allocating competencies to a job the focus needs to be on the key competencies. The first and most dramatic mistake organizations make is to allocate as many competencies as possible to cover every single item of work. By so doing, it makes the task of measurement unattainable. But, if organizations are practical and focus on what competencies are critical or key to a particular job, then the task of measurement and doing training needs analysis become attainable and realistic.

The second important word in the definition of competencies is behavior. We can see, measure, and improve behaviors as they consist of skills, knowledge, and experience.

Having a proper competency framework provides organizations with three essential outcomes. Competencies provide us with

• quality assurance

• conformance to standards

• doing things in a safe and legal way.

Without such standards, it is easy to see how mismanagement seeds economic downturns. The economic downturn a few years ago is a classic example.

The abuse and misunderstanding of how competencies work has meant that in many organizations their overcomplicated approach has significantly reduced productivity. In an attempt to rectify this, we have set out from scratch how competency frameworks should work as they can be a positive contributor to productivity and more importantly have credibility with the business users. Regardless of what approach you take or which model you use, simplicity and clarity of approach are essential if you are to maximize your investment in your employees.

To get the most from a competency approach, managers need to fully understand how competencies work and why they are essential. From practical experience, it comes down to each employee having no more than eight competencies, with six being the average. Key competencies are the ones that make the difference.

To make this clear, there is a complete worked example.

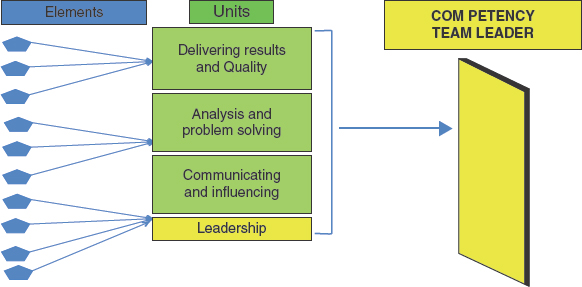

The first is an illustration of how a team leader competency is constructed. The smallest elements are seldom individually rated, and training for these parts typically occurs on the job.

The competency unit is of key interest as this is what we measure and provide training for as need arises.

The all-important units and their relationship to the competence.

The organizational requirement of competence is essential from the viewpoint of a training needs analysis. Although competence impacts every individual, the requirement for competence has already been scoped, approved, and funded at the corporate level. Therefore, although competencies appear to be an individual training need, they are indeed part of the organizational requirement that guarantees and gives conformance to organizational standards.

From a training needs analysis point of view, competencies are challenging, especially when they do not quite match a training course or a packaged solution. Identifying the appropriate training to achieve a higher level of competency is subject to broad interpretation.

Before embarking on an exploration of training needs, minimum and maximum standards need to be set for the competency framework within your organization. Although it is unlikely that you know, right off, the minimum, average, and maximum competency levels required in your organization, these data are essential when you conduct your training needs analysis. For example, if the minimum competency level is 50 percent, the average competency is 70 percent, and the maximum competency is 85 percent, then you can identify the priority for the training needs analysis resulting from the competency level of the individual. This is typically recorded at performance appraisal, which is discussed later.

Let’s look at the example (Figure 4.3). The competency is a team leader. Each page is a unit. You will soon see how this fits in with the schema.

Figure 4.3 How competencies are structured

Competencies

Competency Unit |

Definition |

Anchor |

Delivering Results and Quality |

Directing effort to the achievement of objectives |

Ensures satisfactory team delivery of defined goals, overcoming most problems within one’s own area of specialization |

Analysis and Problem-Solving |

Analyzing information effectively and drawing sound conclusions |

Evaluates available information, reaching decisions on the basis of key facts and practicality of solutions |

Communicating and Influencing |

Achieving understanding or gaining acceptance of ideas and proposed action |

Prepares the case fully, stressing the benefits to be gained and inspiring confidence in one’s own views |

Leadership |

Getting the best from others |

Monitors progress toward achieving clearly defined shared objectives, provides feedback, support, and encouragement to individuals on specific tasks |

Unit One—Delivering Results and Quality

Definition: Directing effort to the achievement of objectives

Anchor: Ensures satisfactory team delivery of defined goals, overcoming most problems within one’s own area of specialization

Positive Indicators—Elements |

Negative Indicators |

• Monitors progress of individuals against their targets; encourages achievement • Tackles bottlenecks/backlogs in the system, and looks for ways to clear these quickly • Refers issues upward quickly to get action • Continually reassesses priorities to focus energy most productively • Consults external specialists to resolve problems outside one’s own specialist area rapidly • Gets “all hands to the pumps” • when dealing with priority, or • “emergency” situations • Adopts a flexible approach to work; is prepared to commit extra effort whenever necessary • Takes immediate action to rectify slippages |

• Does not monitor progress against clear targets • Delays taking decisions until forced to do so • Avoids taking responsibility for one’s own work and that of others • Turns immediately to others for help in resolving situations; does not persist in trying to resolve problems • Fails to respond immediately to slippages within the project • Delivers work that will need amendment or further effort later on • Pursues avenues of interest not set as a priority • Repeatedly finds reasons why tasks could not be completed on time or to the desired quality |

Unit Two—Analysis and Problem-Solving

Definition: Analyzing information effectively and drawing sound conclusions

Anchor: Evaluates available information, reaching decisions on the basis of key facts and practical solutions

Unit Three—Communicating and Influencing

Definition: Achieving understanding or gaining acceptance of ideas and proposed action

Anchor: Prepares carefully, stressing the benefits to be gained and inspiring confidence in one’s own views

Positive Indicators—Elements |

Negative Indicators |

• Prepares facts in advance of meetings • Considers full impact of proposals before putting them forward for consideration • Talks in a positive manner to inspire confidence • Anticipates likely questions and prepares counterarguments • Keeps the message simple; states the facts and objectives • If unsure of the details, commits to finding out for the next meeting • Answers questions directly • Clarifies the needs of other parties in meetings • Persists in putting forward argument • Uses graphics in a presentation where possible • Explains the logic behind changes |

• Delivers an unstructured argument • Makes up arguments when one’s own case is questioned • Presents in a flat and monotone fashion • Gives way quickly when others raise counterarguments • Loses interest if an agreement is not forthcoming • Uses jargon or technical terms others may not understand • Loses patience with those who do not appear to understand the argument put forward |

Definition: Getting the best from others

Anchor: Monitors team morale, provides feedback, support and encouragement to individuals on achieving objectives

• Sets realistic but challenging goals by breaking down overall targets/objectives • Makes time available to staff to share expertise/knowledge • Conducts regular meetings to review individuals’ performance • Conducts quarterly appraisal meetings that focus on development and potential for progression against objectives • Gives negative feedback in private; points out implications of the approach taken • Conducts regular team meetings to communicate information/review team progress and team goals and to praise successes and build team spirit • Identifies training needs of staff and supports with training opportunities • Regulates the workload of staff; doesn’t overburden them • Gives staff clear instructions as to what is required on tasks, and to what standard • Ensures team members are fully briefed on task plans and the background • Provides constructive feedback to help individuals overcome problems or improve their performance • Understands what motivates individual members of staff, e.g., pay, career progression |

• Maintains distance from staff • Works on an “us” and “them” basis • Is destructive when giving staff negative feedback; uses authoritarian approach, is sarcastic or punitive in making comments • Does not communicate successes to the team • Does not make time available to staff • Fails to praise work well • Expects others to be motivated as a matter of course; does • Adopts a controlling approach; does not encourage staff to take ownership of their work • Offers no support for personal development |

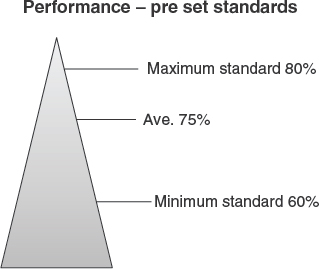

Measuring Competency Levels and Getting the Best from Training

What’s the competitive advantage of this approach, for example, focusing on measuring only units? First, we need to be realistic about setting organizational competency standards in line with the key competencies. In Figure 4.4, the minimum competency standard is set at 50 percent (Miller 2017b)

Figure 4.4 Setting competency standards

In other words, management should not recruit anyone below this minimum requirement. The company standard is shown at 70 percent (Figure 4.4). Any employee falling below that competency score should automatically get training. Once an employee reaches 70 percent (depending on the job), then he or she is said to have attained the required employment standard. As 90 percent of all training will come from these data, training needs can now be automated into our AI system. The software now exists to do this, and both competence and performance can be accurately recorded and translated into precise training needs. This will save time and, of course, cost.

Key points about competencies:

• Competence guarantees quality, safety, and conformance to standards. A lack of competency standards in organizations undoubtedly contributed to many of the financial failures.

• Measure what matters—the units from critical competencies only.

• Set up standards—minimum, company standard, and top-end competency scores.

This will clarify your organization’s competency levels, strengths, and weaknesses. To make this a success, you need to involve all of the senior managers to get not only the buy-in from them but also a good understanding of how the competency system works.

How to Measure and Automate Performance Data

Performance is raw output, how much we do. Performance is measured in many ways, including the following:

• Speed

• Time

• Efficiency

• Unit cost

• Volume

Most companies are overstaffed by 15 to 20 percent and, of course, by a much higher percentage in the public sector. Published figures in late 2009 by the UK government showed that there were 50 percent too many people in the public sector, and specifically in the Public Health Service. It was reported by McKenzie consulting in September 2009 that 1 in 10 employees in the health service could be dispensed with. In a survey of public sector employees in September 2009, 89 percent felt that budgets and public spending were managed inefficiently.

What kind of performance is expected should be made very clear in the contract of employment, although companies should seek legal counsel in this regard as employment law statutes vary geographically on this issue. On the other hand, performance levels above those required should be locked into a bonus or reward system. If the original criteria are correctly set, it should be difficult for employees to do more in the same time, since in theory, they are working at their optimal level. So, you will need to make the decision—bonus or overtime—but not both.

Performance expectations (above required performance) should be established during the performance appraisal and updated throughout the year.

Measuring of Performance can be done in three different ways; these are approached depending on the type of business you work in, the country you are employed in, and finally the culture of the company or organization that you are part of.

1. Performance measured by time worked. This works well if you have managers who do manage. Also, certain cultures are very work focused and when they are at work—work hard. This mainly applies to China where hard work by the hour is part of the culture. In 2016 a survey was carried out in the Middle East to determine how many hours people worked. The following results were obtained:

Talented workers—17 percent worked 32 hours a week

Average worker—61 percent worked 22 hours a week

Poor performers—22 percent worked 5 hours a week

I have displayed these data in many (non-Asian) countries, and very few people seem surprised about the results, particularly those in the public sector.

2. Performance through individual target setting. This is a real winner, but it carries with it a big warning. Properly set and monitored targets with big bonuses produce massive results, provided

a. that at the end of the year, the bonuses are not subjected to a forced ranking.

b. that the bonus must be subjected to the average competence and reliability scores being achieved.

c. that the bonus is directly aligned with organizational achievement.

3. Performance through team target setting. This has very much the same criteria as the aforementioned, but uses a Hopper Bonus scheme where all participants (The Team) need to meet the score requirement for competence and reliability before any bonus can be earned.

Companies that take their eyes off of this soon find themselves in real financial difficulty. There are three approaches to get performance; each has its advantages and disadvantages. The first is self-motivated staff—these employees are painstakingly recruited and know what needs to be done. They require little motivation or supervision and work whatever hours are needed. They are typically rewarded via some form of share/stock option scheme.

The second is the managed workforce—employed but not trusted. Management runs a strict and inflexible routine. In this instance performance is achieved by hours worked, the manager taking responsibility for prescribing work and making sure it is done within the time allocated.

The third and most abused is the setting of objectives and stretch targets. The old-style managers are not good at doing this and are constantly undermined by having forced ranked bonus schemes determining who gets what bonus at the end of the year. A consistent theme in performance—it must be measured.

Regardless of which of the three schemes you use, the approach for measurement is the same as for competency. Management needs to set minimum company standards and top-end figures for performance.

As with competency (quality), no bonus or additional payments should be made for anything below required average standard. In fact, if required performance is not achieved, then employees’ basic salaries ought to be reduced. Check this out carefully as it may not be legally possible, although I think it is morally right. All of this highlights the need for adopting thorough recruitment practices; for getting guidance on this, look at how good Google are at this—and look at their bottom-line performance figures.

You may be wondering why productivity is not 100 percent on our chart. Well, two very separate components affect this. The first is time. In a 38-hour week—no one can work 38 hours—we have PT&C time plus a lunch break. So at best the working week will be only 34 hours of available time.

Poor overall performance is then compensated for by the managers who demand more staff, resulting in overstaffed organizations.

Gathering performance data is, of course, done at performance appraisal. We use the same process that we do for competency information shown in Figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5 Setting performance standards

Now what’s important is that both competency and performance are now on linear scales 1 to 100 perfect for AI to pick up at a later date.

Reliability—What Is It? How to Measure and Improve It

Reliability is a dimension of value that is very rarely measured by workforce management. So, what is reliability and why should we take it seriously? We already know the costs of an employee and what that cost is per day. We also know the cost of an employee per hour. Reliability is a measurement of whether or not that person works for the hours that he or she is paid.

Unreliable people tend to commence work late, often leave early, and have a remarkably high level of unsubstantiated sick leave.

The two critical areas for us to focus on are sickness and unsubstantiated days off (either from uncertified sickness or other reasons). The terminology makes this authorised or un authorised absenteeism but the global tile used is reliability. Why we need to get on top of this issue is that it cost lots of money directly and hurts employee morale indirectly. That is why measuring reliability is increasingly an essential factor in workforce management and reporting the cost of unreliable people is a significant business cost factor.

When a public organization in the United Kingdom was investigated, it was found that employees were shown to have had 895,000 days off (was this sick leave?). With 50,000 employees, that equates to each employee having 17.9 days off on average every year.

Fortunately, mathematically it is now possible to calculate by individual, section, or department the direct cost of reliability. This can also be projected using our predictive workforce management tools showing the cost over 5, 10, and 15 years. For all organizations this figure is so significant it cannot be ignored.

For example, if one person comes to work late every day (just 30 minutes) and has 14 uncertified sick days in a year, then what is the cost in reliability for this employee for 1 year?

£46 × 0.5 × 0.226 = £5,198

£46 × 8 × 14 = £5,152

Total cost = £10,350

If 20 percent of our 3,000 strong workforce fall into this category, then the real cost per year is

600 × £10,350 = £6,210,000

So, for our three-time scales of 5, 10, and 15 years, that is:

5 × £6210,000 = £31,050,000

10 × £6210,000 = £62,100,000

15 × £6210,000 = £93,150,000

From work on reliability carried out over many years, these are very conservative figures. If this does not grab your attention, then do the calculation on the basis of A City Councils figures: 17.9 days off each year for each of the 50,000 people. An AI system would never have allowed this to occur; there is a lot to be said for automated processes.

Measurement of reliability − new tools = great results

When gathering data, we use formula 2 and then the figures are converted into a linear scale (Figure 4.6), so that we can correlate them for other comparative work.

Using your facts you can now do a benchmark to find out how reliable your employees are and what’s the cost to the organization. It’s management’s job to rectify the fault if you have a big issue here—not yours. You have identified the problem, costed it out, and provided the management information on the cost to the organization. Ongoing monitoring will make this a key human capital measurement factor.

It would be prudent to come up with a figure of where you expect the organization to be on the chart—100 percent is not realistic.

Thus in 2017, using an existing but old formula (the Bradford formula), we have mathematically adjusted the output, so that the output runs on a 0-to-100 scale, with the indicators showing when counseling is needed, when a first verbal warning is given, when a first written warning is given, when the next written warning is given, and when a final written warning and dismissal is given. AI will, of course, do this automatically.

Figure 4.6 0-to-100 scale set against Bradford formula scores

Reliability, with competence measurement and productivity measurement can now be measured as one integrated system, AI will integrate and report on the results. The data are fed into this program and the appropriate actions to be taken are displayed to the manager, so that there can be no oversight, slippage, or forgetfulness to take action.

As mentioned before, reliability is one of three key indicators, which together equal productivity. It is essential that any decisions on increments, bonus, allowances, or promotion be taken only after viewing the total picture. Very often reliability is not taken into account during interviews or for selection and promotion. Poor reliability has a marked effect on other employees’ motivation to such an extent that it severely impacts on organizational efficiency if it is left unchecked.

The value of time and people—essential calculations and information The cost of poor reliability is enormous not only in straight financial terms, for example, in the matter of paying an employee’s salary, but also in regard to missed deadlines, slippages, and low-quality work. Therefore, I am sure you can see that reliability is a crucial indicator and essential for our dashboard.

Can poor reliability be identified?

Significant evidence exists that likely poor reliability can be shown using personality profilers.

Other research has been carried out in regard to the impact of job satisfaction and absenteeism on an employee, and there seems to be clear evidence of positive correlations between high-frequency absenteeism (many short absences from work) and dissatisfaction in the job.

This further shows the importance of doing regular staff satisfaction surveys to ensure and measure the relationship between absenteeism and the staff satisfaction scale. This is so important that it features on our dashboard productivity indicator scale.

Projections of lost time through poor reliability

Using formula 2 (referred to in Chapter 9) and the appropriate software, it is possible to get a linear numeric score (0 to 100) that shows reliability. Then by modeling the data using a Monte Carlo–type simulator, you can project the reliability factor 5 to 10 years into the future and also what the financial costs will be to the organization.

As we have seen before, we now have the data on a 1-to-100 scale, which is perfect for our transition to AI (Figure 4.7).

Aligning Performance Appraisal for Future Needs with AI and Other HR Processes

Ask any professional HR manager about the benefits of performance appraisal and you will hear all the normal attributes—a good development tool, essential to determine training requirements, a vital tool for motivation, ideal for gathering data, for setting performance objectives, and for measuring employee competence, and a tool to justify bonus and rewards, and so on.

Figure 4.7 The productivity components

The final comment is generally that it is best practice.

Ask the same question to a senior line manager, and the response will usually be very different.

The majority of managers seem to have the view that appraisal time does not justify the result. This is a conflict of opinion, and so who is responsible for the output and added value of the appraisal system?

Who has responsibility for the performance appraisal?

If you decouple measurable output from performance appraisal, then most HR professionals will put their hands up to owning the process.

However, once the term measurement output is mentioned, then the responsibility for the process and the output seems to transfer quickly to line management.

With performance appraisal being the single most significant tool for objective setting and performance measurement, how can it degenerate so quickly into an organizational orphan?

In the vast number of performance appraisal systems that are in place, it is inconceivable that so much can be spent on a process that delivers so little yet is still viewed as best HR practice.

This is due to a common myth that best practice must always produce best practice results. If it is best HR practice, then perhaps any HR bonus should be calculated on added value measurable output from the system.

As the process is a shared responsibility with the line management, the output must form the basis of a shared key performance indicator.

Before you sign up to this being a good idea, you need to read on and see what is involved in getting benefit from this system.

Severe defect in most appraisal systems

The operating fault of most current systems lies not just with the process and lack of accountability for bottom-line results but with a far simpler issue, an issue that is cheap, quick, and easy to remedy.

After speaking with over 1,000 HR professionals worldwide from a broad spectrum of industries, it became evident to me that in the majority of cases the focus on appraisal makes positive, measurable outcomes impossible.

The consensus seems to be that once the appraisal system is installed, after the first year a pattern of how the appraisal runs becomes evident. The actual time spent doing the appraisal seems to vary to within plus or minus 15 minutes, the mean tending to be 1 hour in duration. What is of great interest is how that time is used.

It seems that the majority of the appraisal time is spent reviewing the previous year activities. In fact, the figure quoted amounts to a massive 80 percent, that is, 80 percent of the time is spent on looking back on performance against objectives and identifying training needs and other factors that should not be discussed at a performance appraisal. We term this the rearview mirror effect (Miller 2017a).

The fault with this approach is that nothing can be done about the past or past performance—what’s past is history, nothing will change what’s already happened.

The only thing managers can plan for and be successful with is the future. This obsession with the previous year’s performance and activities is the single biggest reason for the failure of appraisals. Therefore, the rearview mirror approach is not compatible with today’s fast-moving dynamic business approach.

Such a strong past focus leaves only 20 percent of the appraisal time for future focus. It is, therefore, not surprising that objectives are poorly set and little, if any, real measurement of performance is planned or takes place. Because of this, managers are unwittingly setting their staff up for failure.

This effect of setting employees up for failure is genuine and costly. Training is then identified on the basis of failure or weaknesses.

When an employee fails, the feeling of failure, or of a job not well done, pushes motivation down and hangs like a shadow of doom till the next appraisal, so training (usually the cure-all solution) is prescribed on the basis of a failure that happens probably 9 months before the appraisal.

Training then identified at appraisal goes through the system, and it can be 6 months before it takes place.

To recap, in this example, a total of 15 months elapsed time has been taken to rectify a past mistake or shortfall and provide a solution, in this case, training. This retrospective approach to appraisal makes no business sense and could easily be avoided by taking a different approach. HR managers, line managers, and indeed managing directors, seem to be unaware of the real cost of an appraisal system.

If the appraisal is the most critical goal-setting tool an organization has, then we must be confident that it will yield a good return on investment and add value. So, let’s examine the cost of an appraisal for a company employing 5,000 people with an average employee unit cost of £46.00 per hour.

For each appraisal

Also, it would be fair to add the cost of misdirected training identified from appraisal. This could be as high as 70 percent of the training budget, the cost of which would need to be added to the calculation.

In our example, we have a cost to the business of £621,000—to get just a simple return on investment, we need to get every year £621,000 of measurable bottom-line benefits. Can your appraisal system deliver this type of performance?

If you go beyond return on investment to seek added value, then it would be reasonable to expect to see a 20 percent added value every year. In other words, every year the system is in place we should expect to see minimum measurable benefits of £745,200. Can your system deliver this type of business performance?

What needs to change to produce real advantage from performance appraisal?

Producing real results from appraisal, be it development, competency improvement, or business performance, is achievable by merely changing the focus and emphasis of any traditional appraisal system.

The only thought any manager should have at appraisal is “How can I set this person up to be successful?” With that thought clearly in mind, the rest should be straightforward and fully managed by AI.

Time reviewing the past (which we cannot change) should be reduced to 20 percent of the appraisal time—looking forward, setting SMART or WWW objectives, and discussing success should be our prime and only focus. At least 80 percent of focused attention must be for success in the future.

If for any genuine reason an employee (appraise) is unable to meet an objective because of a lack of skill, knowledge, or experience, then some form of action, perhaps training, needs to be arranged before the date of the start of the objective.

This is a critical step that needs to be taken if an employee is to be successful—training first before meeting an objective. New focus = new results.

Once objectives have been set and agreed, the measurement of results must be an ongoing, a regular, and a scheduled activity—after all, is this not the basis of why we employ managers? This measurement must take the form of an ongoing and performance-focused interaction between appraise and appraiser.

The focus on everyone being successful should be the manager’s overriding aim. This is not easy with difficult and challenging employees, the lazy, and the unengaged. A good manager should apply the same technique to everyone—change will happen only when trust and credibility have been established (Miller 2017a).

Is Appraisal a Motivational Tool?

Is appraisal a motivational tool? Just ask yourself, will employees be more motivated by failure—the old rear mirror approach; or will employees be more motivated by success in an environment that breeds success; the forward success-driven approach.

Motivational success through appraisal can be measured. Do some statistical analysis such as measuring sickness levels before adopting the new approach and then examining the sickness levels after. Also, look at staff turnover both before the adoption of the new system and after. Staff satisfaction surveys are also a useful indicator. Where does 360-degree appraisal fit with the new model?

Three hundred and sixty-degree appraisal is yet another shining example of what is believed to be best practice. Does it work?

How much does it cost to run the process? Is it going to be of any use in the AI world?

The term motivation is often wrapped in with the benefits of appraisal. If the appraisal is an essential motivational tool, then managers need help to get the new approach right.

Performance against agreed targets needs to be measured and discussed throughout the year, with success celebrated as appropriate. Then, when the next round of appraisals starts, the majority of employees will be confident in the knowledge that you are focusing on making them successful. Success breeds success.

Most managers have difficulty with setting measurable performance targets. Although this is a vital part of the job, it is seldom tackled with much enthusiasm. Short workshops on setting specific objectives are an excellent way to start, using the SMART process to help them focus.

Another good investment would be a briefing on the value of coaching and using Management by Walking About, which is an excellent tool to keep ongoing involvement in place.

A key input factor for managers’ and supervisors’ bonuses should be based on the percentage of performance achieved during the year. By linking directly to pay, the incentive is created to make things happen.

Organizational Benefits

Changing the focus for appraisal is a case of everything to gain and little to lose.

In AI terms, performance appraisal correctly focused is the hub for most HR activities.

Some of the organizational benefits that should be seen include projects delivered on time and within budget, reduced absenteeism levels, improved staff morale, reduced training budget, a more agile organization, and lower staff turnover in the long term.

The process will clearly identify poor performing managers, supervisors, and employees, and will enable a definite and measurable impact on the bottom-line to be seen.

Although this might seem appropriate only to the private sector, many of the benefits mentioned do map very nicely into the public sector.

There should also be a change in the way HR is viewed, as this gives a clear indicator that HR is adding value by using business skills to enhance business performance.

Connectivity has become an issue in the United Kingdom, with surveys showing that staff increasingly have low connectivity with their employers.

As the new appraisal focus is based on shared responsibility for success, there will be a greater feeling of inclusion and the possibility for building long-term connectivity.

Rewards based on measurable performance are also fair and equitable and will be seen as such.

Those showing potential through improved performance will be the first candidates for development, training must take on a new and specific role that is directly linked to achieving business objectives, which is a prerequisite for talented people. Finally, there will be an overall view that we are doing the right thing and something that is worth doing—because it is measurable and taken seriously.

The AI Impact

AI can run almost all of this process. The two critical requirements for productivity coming out of Appraisal are Performance scores and Competency scores. The former is the main feed into an AI-run bonus scheme (discussed later in Chapter 7). Competencies determine training needs allowing Training Needs Analysis to be fully automated (Chapter 5). AI will also be able to manage continuity of the process and will adjust any rouge scores. These scores are like to come from appraisal where the manager gives higher scores for favored employees or training courses as a reward.

Doing this seems very simple and it is. What AI will significantly add is much tighter control of the process and intrinsically link this process directly with training, evaluation, calculation of Return on Investment, and pay and compensation.

Many HR functions have some of these data, but I have yet to see it work seamlessly. It is a perfect fit for process redesign and for using AI.

Often a missing link will show if a performance appraisal adds value (Figure 4.8). This would be a smooth operation for AI, and the flow of useful management information would be truly beneficial.

Figure 4.8 The appraisal big picture

Is performance appraisal a motivational tool—sickness levels are a good indicator of staff happiness and motivated staff—the correlation would also be managed seamlessly by AI.