Introducing Serendipity

T.M. Race1 and S. Makri2, 1New College of Florida, Sarasota, FL, United States, 2City University London, London, United Kingdom

Abstract

Serendipity, the happy accident of discovery, not only manifests itself in scientific discoveries and modern innovations, but also our work and everyday activities. It has the potential to act as a catalyst for the acquisition of new knowledge, a jumpstart to creativity, and an energizer when we experience a slump in problem-solving. While often referred to as a “happy accident,” serendipity is not entirely due to chance; we can “prepare our minds” for serendipitous opportunities and need to seize them when they present themselves. Although serendipity involves an element of luck, it is more than blind luck. It cannot be controlled, but it can be influenced. It cannot be created on demand, but it can be cultivated. This book examines how we can cultivate serendipity in the context of accidental information discovery—by making room for serendipity in our lives (see chapter: Making Room for Serendipity) and by designing academic learning environments (see chapter: Teaching Serendipity) and digital information environments (see chapters: Serendipity in Current Digital Information Environments and Serendipity in Future Digital Information Environments) that create opportunities for it.

Keywords

Serendipity; accidental discovery; information discovery; information seeking; innovation; creativity; scientific discovery

Journalist Ted Gup published “The End of Serendipity” in 1997. In this essay, Gup compares his own boyhood experience of looking for information in a print set of the World Book Encyclopedia to his sons’ experiences of searching the World Book Encyclopedia on Compact Disc (CD)-ROM. Gup recognizes that the print version encourages one to browse the resource, bypassing the alphabetical structure and paging beyond the information item of interest—producing that elusive accidental interesting something. In contrast, the encyclopedia CD-ROM offers a direct route to the sought information via a keyword.

By 1997, the digital information landscape included the CD, the Digital Video Disc (DVD), the World Wide Web, and Dot.Com businesses (computerhistory.org) (Computer History, 2015). Communication via e-mail was commonplace, and digital citation indices like AGRICOLA, CiteSeer, and Web of Science facilitated electronic citation searches. Gup’s essay articulates one extreme of our perceptions of this new information landscape: while opportunities for accidental discovery were still present in the CD-ROM format, they were masked in the tools of efficiency-quick retrieval, high precision versus the more transparent “unconnected highways” (Gup, 1997) of the printed page. A similar argument can be made for modern-day Web search tools; while we have access to much more information than was available to us in 1997, search has only become more precise—helping us to better find information we need but hindering us in accidentally discovering information we need, but did not realize we needed.

Several “Letters to the Editor” were submitted by readers of Gup’s essay. Some readers agreed that advances in technology heralded the end of serendipity. However, others described their own positive experiences of accidental information discovery in digital information environments. Noting the exploration afforded by hyperlinks, Patterson (1998) comments, “I think that I can safely say that serendipity is alive and well.” Grafflin (1998) writes, “If you never use a web browser except to open a specific U.R.L., and if you never allow yourself to follow any link from that U.R.L. to another, you will have a more impoverished experience than if you leaf through an encyclopedia. But if you use the Web in a natural and relaxed fashion-searching, linking, backtracking, you will find a world infinitely more diverse than Mr. Gup’s beloved World Book Encyclopedia.” The “Letters to the Editor” demonstrate three key points:

1. Accidental information discoveries are useful. Gup was not alone in his identification of the value of accidental discovery—other people also found it a highly useful way of acquiring information.

2. Accidental information discoveries are not entirely “accidental”—they can be influenced. Characteristics of an information environment could influence the opportunities for these discoveries to occur.

3. Accidental information discoveries can be encouraged through design. Digital information environments can be designed to encourage these opportunities (eg, by allowing people to dodge around the imposed structure, through alphabetical arrangement or to explore beyond the specific item retrieved—by following hyperlinks).

Furthermore, Grafflin’s letter highlights the importance of adopting a certain attitude of mind; approaching information acquisition in a “natural and relaxed fashion” (p. B10). Accidental information discovery can be influenced not only by the nature of the digital information environment, but also by the nature of the person using the environment. Some people are more prone to accidental information discovery than others (Erdelez, 1999) and while it involves an element of “accident” and therefore cannot be directly controlled, it can be influenced (McBirnie, 2008). For example, creative professionals reported that they were more likely to experience serendipity when they varied their routines, relaxed their intellectual boundaries, and seized opportunities (Makri, Blandford, Woods, Sharples, & Maxwell, 2014). While attitudes of mind are often shaped by individual beliefs and value systems, they can also be fostered and nurtured through teaching. Therefore, just as digital information environments can be designed to create opportunities for accidental discovery, so can learning environments; Nutefall and Ryder (2010), for example, designed a university writing course that incorporated aspects of accidental information discovery.

Therefore, although often referred to as a “happy accident,” serendipity is not entirely due to chance; we can “prepare our minds” to make accidental information discoveries and seize serendipitous opportunities when they present themselves—by mining the value from our discoveries. Although serendipity cannot be directly controlled, it can be influenced; we can create opportunities for it through the design of physical, digital, and learning environments. And although serendipity cannot be created on demand, it can be cultivated. This book examines how we can cultivate accidental information discoveries—by making room for serendipity in our lives (see chapter: Making Room for Serendipity), by incorporating it into pedagogy (see chapter: Teaching Serendipity), and by designing digital tools to create opportunities for it (see chapters: Serendipity in Current Digital Information Environments and Serendipity in Future Digital Information Environments).

Before focusing on how to cultivate serendipity, it is necessary to understand the history and nature of the phenomenon. In the remainder of this chapter, we provide a brief overview of the history of serendipity and its role in important scientific discoveries, creativity, and innovation and, finally, in accidental information discovery.

History of “Serendipity”

Serendipity is “the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way” (Oxford English Dictionary, 2013). In The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity, Merton and Barber (2004) chronicle the origin of the word “serendipity,” incarnations of use, and meanings in relation to scientific discovery. British writer and collector Horace Walpole coined the word in 1754, in a letter to his friend, Horace Mann. Walpole’s inspiration was a story, “The Travels and Adventures of the Three Princes of Serendip.” In his recounting of the story, the three princes successfully solve problems by carefully analyzing information gained accidentally, and forming correct deductions. Walpole’s personal emphasis identified three key elements for “serendipity”: accident, “sagacity,” and the discovery of something that was previously unknown (Merton & Barber, 2004, p. 2).

Walpole’s new word, “serendipity,” was not seen in print again until 1833, when his letters to Horace Mann were published (Merton & Barber, 2004, p. 22). Upon its resurrection, serendipity found an audience more receptive to its use, and the beginnings of an ongoing discussion regarding serendipity and its value to discovery. Serendipity is a subjective, shape-shifting concept: individual attitude and perception define its worth. To illustrate, Merton and Barber cite two different reports of Heinrich Schliemann’s archeological discoveries. C.W. Ceram (1986) (Gods, Graves, and Scholars) gives little weight to Schliemann’s “unexpected finds.” However, author Hendrik Van Loon (1974) in The Arts describes these unexpected discoveries as “the very exemplification of serendipity, and stresses how much of value he stumbled on in the course of his excavations, over and beyond any anticipation” (Merton & Barber, 2004, p. 20). Both Ceram and Van Loon acknowledge that chance played a role in discovery, but each assigns a different degree of worth to the role of happy accident.

Serendipity and Scientific Discovery

Historical accounts of significant scientific discoveries embrace serendipity as a key factor. Such accounts include:

• a method to measure the distances to stars (by astronomer Henrietta Leavitt; Lightman, 2006, p. 32),

• the discovery of penicillin (by biologist Alexander Fleming; Lightman, 2006, p. 32; Gest, 1997, p. 24),

• the discovery that elephants communicate via ultrasound (by biologist Kay Paine; Hoffman, 2005, p. 69),

• the discovery of microbes (by tailor Antonie van Leeuwenhoek; Hoffman, 2005, p. 69),

• the discovery of the cholera vaccine (by Louis Pasteur; Gest, 1997, p. 22).

These investigators achieved breakthroughs by being open to accidental discovery, being able to make connections, and being able to apply the new knowledge generated in a valuable way. Their experiences affirm Friedel’s comment: “There are philosophers of science who suggest, in fact, that serendipity is fundamental to all science, especially the most creative and important” (2001, p. 37).

Closer study of 20th century scientific discoveries reveals that serendipity does play an authentic role, despite its mutability. In his “taxonomy” of discovery, Lightman describes serendipitous discovery as “mysterious,” “unpredictable,” and seeming “… the least accessible to analysis and understanding.” Serendipity for scientists is “something they were not looking for” (2006, p. 31). Serendipity “lies beyond the scientific process” and is a clue to how our subconscious mind works.

With a similar goal of classifying serendipitous discoveries, Friedel (2001) identifies three types of happy accidents:

• Columbian—Columbus was searching for the Far East, but found America instead. Columbian serendipity occurs when “one is looking for one thing of value, but finds another thing of value” (p. 38).

• Archimedian—Archimedes solved the question of how to measure the volume of an irregular solid while taking a bath (p. 40). Archimedean serendipity occurs when one finds “sought-for results, although by routes not logically deduced but luckily observed” (p. 38).

• Galilean—Galileo did not have a preconceived idea of what he would see through his telescope. Galilean serendipity occurs when we discover something valuable that we were not intentionally seeking (p. 40). Friedel writes that “Time and again in science we see this facility for using new instruments or capabilities to generate surprises” (p. 40).

That the paths to serendipity vary should not be a surprise. The multiple factors that engender serendipity are predicted by Walpole’s intent: Merton and Barber contend that Walpole built ambiguity into serendipity. “What Walpole obscured in his explanation of serendipity was the nature of the object discovered: whether it was a known quantity or an unknown quantity; whether it was something that might have been expected (retrospectively prophesied) or not; and finally, whether it was of any significance or not. It is the latitude that these obscurities give to individual interpretation that the complexity of meaning of serendipity has its origin” (Merton & Barber, 2004, p. 20). Serendipity may be initiated under varying circumstances. In addition, discussions surrounding scientific discovery and the role of serendipity center on contributing, yet competing, concepts of chance and sagacity, the individual knowledge needed to take advantage of chance (Merton & Barber, 2004, p. 20). There is no fixed and determined recipe for serendipity, but rather multiple situations that may foster accidental discovery, in combination with a specific person’s mindset.

Serendipity, Creativity, and Innovation

One of the most valuable benefits of serendipity is that it can be a route to creative problem-solving and innovation. Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow (2004) define creativity as “the interaction among aptitude, process, and environment by which an individual or group produces a perceptible product that is both novel and useful as defined within a social context.” Sabelli (2008) identifies diversification as a key component of creativity. As an example, Sabelli describes biotic patterns as creative, they “generate diversity, novelty, and complexity” (p. 2). Similarly, human innovation is a creative process (p. 2). “Innovations are creations, not accidents, and they always spring forth from the conjunction of many concurrent forces, conscious and unconscious” (p. 2). While innovation may be an act of creation rather than accident, accidental discovery can be the catalyst for the act.

Serendipity helps us to innovate, to be creative, by offering us bridges across and beyond our created structures. Ford (2013) cites McCracken (2012): we need serendipity in action, “we need ideas we can’t possibly guess that we need.” These accidental discoveries shift our thinking, helping us to view issues and problems differently, and jumpstarting connections between fields of knowledge (Erdelez, 1999; Foster & Ford, 2003).

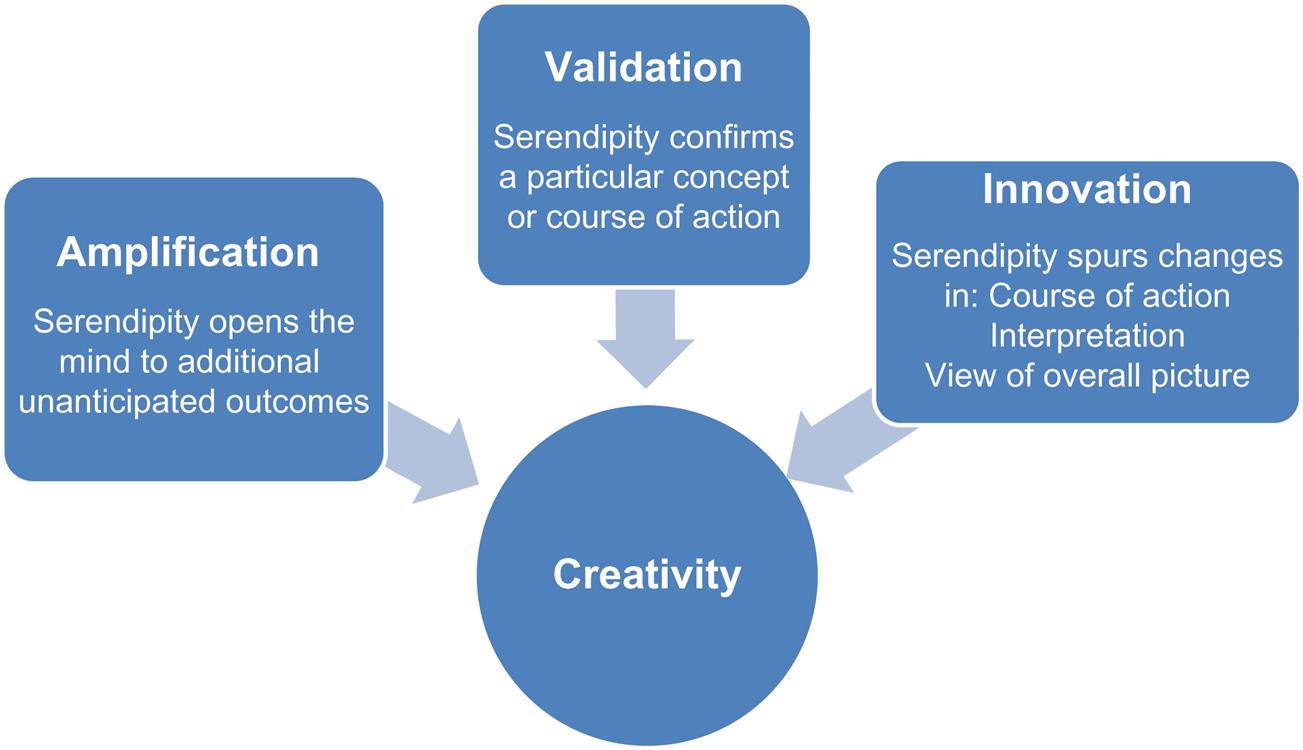

Encountering information that was not previously known or anticipated can influence the creative process in three basic ways: validation, amplification, and innovation. Fig. 1.1 depicts the ways in which serendipity and creativity may interact. In its simplest, most direct effect, accidental discovery may confirm or reinforce an existing concept or course of action (Foster & Ford, 2003).

Accidental discovery may also amplify one’s creativity by amplifying our reception to the unexpected. Once we know that the unanticipated exists and can be useful, we may become open to more possibilities occurring (Sabelli, 2008). It is therefore possible to become more creative by recognizing serendipity and allowing it to become part of our process of problem-solving and creating.

Finally, accidental discovery can stimulate innovation. This influence has probably been the most analyzed, and serendipity may lead to innovation by many means. Serendipity can lead to a change in a course of action (Guha, 2009; Johnson, 2010; McBirnie, 2008); a change in interpretation (Guha, 2009; Johnson, 2010; McBirnie, 2008); and/or a change in the perception of the overall picture (Sabelli, 2008). These shifts in actions, interpretations, or perceptions spawn innovations. The innovation may come via new connections (Nutefall & Ryder, 2010). It may also manifest itself via leaps in discovery, a radical problem-solving beyond known boundaries (Foster & Ford, 2003; Sabelli, 2008). As noted by Makri and Blandford (2012), serendipity “provides new insight or perspective that pushed the boundaries of existing knowledge” (p. 695).

Johnson (2010) identifies serendipity as one of the seven pathways to innovation. In order for innovation to take place, we have to embrace “the adjacent possible”—the possibility that is a little different, on the verge of our normal thoughts. Accidental discovery, whether through dreams or networking with others, is one means of striking on innovative solutions. Johnson cites examples of businesses that have broken down barriers in order to make accidental discovery, and innovation, more likely. IBM and Proctor and Gamble are sharing innovations more openly (p. 125). Nike released more than 400 patents for “environmentally friendly materials technologies” through Green XChange (p. 125). Modern businesses recognize that networking, being open to discovery, can be good for business and responding to change. In his description of dreaming, Johnson notes that “The chaos mode is where the brain assimilates new information and explores strategies for responding to a changed situation” (p. 105). Extrapolating from the chaos of dreams to the business world, too much control limits accidents, including happy ones, and potential of innovations.

Hagel, Brown, and Davison (2010) articulate the link between accidental information discovery and innovation in a different way, describing the “serendipity funnel.” Historical planning models relied on stability, including relatively stable sources of information. The current environment is fluid, information sharing is rapid, and information sources and their relative stability shift. “…Managers today must tap into multiple, fast-moving, informal knowledge flows” (Schum, 2010, p. 67). Knowledge can be a moving target, and therefore the search itself, in order to be useful, may need to be less targeted and more fluid. Accident may play an even more important role in finding the information needed. Managing the serendipity funnel means maximizing one’s opportunity for accidental discovery—for example, communicating with innovators in real time via social networks.

Serendipity and Information Discovery

The importance of serendipity is recognized when we see its results. Major breakthroughs happen in science. Businesses create innovative solutions. Discussing these examples helps to illuminate critical aspects of accidental information discovery. These aspects include the defining characteristics of the occurrence—accident, sagacity, and finding something not sought—as well as the shifting perception of occurrence depending on the individual. Serendipity encourages creative leaps, building links, and fostering innovation. Information is an important conduit for serendipity; accidental information discovery can support scientific discovery, spur creativity, and drive innovation.

Information Science research into accidental information discovery breaks out into three broad and overlapping areas: describing/defining serendipity (often in the context of information discovery), understanding interactive information acquisition [and, in particular, how information can be encountered (Erdelez, 1999) rather than sought], and designing digital information environments that create opportunities for accidental information discovery.

Walpole’s intended ambiguity continues to manifest itself in descriptions of serendipity in Information Science. McBirnie (2008) characterizes these ambiguous aspects: it is rare, but regular; sometimes an active “happening upon,” sometimes a passive “happening” (p. 607). Researchers describe serendipity as accidental, random, unpredictable, elusive, slippery, subjective, positive, exciting, and fulfilling (Foster & Ford, 2003; Hoeflich, 2007; Makri & Blandford, 2012; McBirnie, 2008; Fig. 1.2). Though unpredictable, an important consequence of serendipity is that unexpected information can revitalize a stalling, unsuccessful search by injecting positivity (Erdelez, 1999)—it is after all a “happy” accident.

Early work on serendipity in digital information environments studied the phenomenon in relation to browsing Online Public Access Catalogs (OPACs; O’Connor, 1988; Rice, 1988). Functionality for supporting serendipitous discovery included browsable search indexes and similar article citation retrieval (Rice, 1988). Ford, O’Hara, and Whiklo (2009) extended the relationship between browsing and serendipity, creating a browsable electronic reference book shelf, complete with Library of Congress classification numbers and images of vendor book covers.

Research in the 2000s moved away from studying serendipity in OPACS and toward studying serendipity on the Web. Campos and de Figueiredo (2001) built Max, a web browsing agent. Max mined interesting “information surprises” by generating search queries based on interests users provided in an individual profile. It then used Google to search the web using those queries and sent the results back to users by e-mail. Early results showed that these surprises helped to develop the search, by initiating new interests or modifying the search itself. Toms (2000) also studied opportunities to encourage accidental information discovery on the Web. In this study, participants were provided with articles that were both similar to and different from their initial query. The resulting serendipitous discoveries supported the notion that systems can be designed with accidental discovery in mind.

Because so much of serendipity depends on personal perception, studies on how people accidentally discover or encounter (Erdelez, 1999) information in digital information environments are requisite to understanding possibilities for designing to support serendipity. Like serendipity itself, potential design interventions for supporting serendipity through design take many forms. Some existing design interventions include: presenting raw data in a navigable system of linked data relationships (Beale, 2007); presenting web browsing results coded to reflect relevance (Beale, 2007); designing system supports that are responsive to changes in cognitive perception of relevance (Cosijn & Bothma, 2006); creating browsable data maps via hyperlinks (Stevenson, Tuohy, & Norrish, 2008); creating interactive visualizations of library collections (Thudt, Hinrichs, & Carpendale, 2012) and creating a “semantic sketchbook” to support reflection and the making of “aha” connections (Maxwell et al., 2012).

Since the 1980s, research interest in serendipity in the context of information discovery has continued to grow. Various terms have been used to describe the phenomenon—information encountering (Erdelez, 1999), serendipitous information retrieval (Toms 2000), serendipity in information seeking (McBirnie, 2008), opportunistic discovery of information (Erdelez et al. 2011), incidental information exposure (Yadamsuren & Erdelez, 2010), and accidental information discovery (the term we adopt in this book). The adoption of different but highly conceptually similar terms might be explained by the slippery and subjective nature of the phenomenon. However, as this emerging research area matures and we gain a clearer understanding of its scope and boundaries, there is potential for common terminology to be adopted. In this research area, a particularly important question that is attracting considerable research interest is “how can we (best) create opportunities for accidental information discovery?” This is the question we focus on in this book.

The chapters that follow examine how we can cultivate accidental information discoveries—creating opportunities for “happy accidents” without undermining the “accident” that ignites serendipity. In chapter “Making Room for Serendipity,” Race examines individual and environmental factors that can support or hinder these discoveries and discusses how we can “make room” for serendipity in our lives by adopting an attitude of mind that is receptive to it. In chapter “Teaching Serendipity,” Ryder and Nutefall discuss how serendipity can be incorporated into academic learning environments; how we can “teach” it. In chapter “Serendipity in Current Digital Information Environments,” Makri and Race review existing digital tools that create opportunities for accidental information discovery. Chapter “Serendipity in Future Digital Information Environments” comprises a collection of essays from active researchers in the field, discussing serendipity in future information landscapes.