“The best way to guarantee a loss is to quit.”

Morgan Freeman

You’ve taken the first step and have begun your career, and now it’s time to move into the next phase: “Sticking It Out.”

How long is this stage? you might be wondering. The short answer is, longer than you think. You won’t just stick it out until you achieve the success you’re looking for. If you’re in this for the long haul, you’ll stick it out until you’re ready to retire. That is, if you do retire. Because artists, as you know, have the luxury of continuing their work long after the age of 65.

Sticking it out means making a decision to stay in the game even when all signs seem to point you in a direction off the board. Sticking it out means weathering the low-lows. It means finding a way to be happy for your friend who just landed a lead when your agent just dumped you. It means practicing the accent for your new role for ten or twelve hours instead of only the two hours you were required. It means showing up for the audition even when you’ve lost all confidence.

In this chapter, we’ll delve into the work involved with choosing to participate in an acting career. It’s all about choice—hard work, tenacity, creating your own opportunities. There will be lean months. There will be entire years when the only acting jobs you get are the ones you create for yourself. There will be eighteen-hour days with two jobs and acting class at night. There will be roles you get but have to give up for one reason or another.

Who Knew?

The overnight success stories you’ve heard of in the business are actually stories of dogged determination—people working quietly, tirelessly for years before that overnight success occurred. Morgan Freeman made his Off-Broadway debut in 1967, debuted on Broadway in 1968, and continued his theater work for years before receiving the Obie Award in 1980. He didn’t find success in film until 1987, in a supporting role in Street Smart, and he landed the films Glory and Driving Miss Daisy in 1988, at the age of 51.

If you want to reach the next stage of your acting career, you must first commit to this stage. In this chapter, we’ll discuss:

• How vocal training prepares you for a career in acting

• What vocal training looks like for the highest paid actors in the business

• Getting headshots, where to meet friends, and where to take acting classes

• How to get an audition, what to wear, and how not to panic when you get there

• The importance of managing your mental health

• How much appearance matters for actors

• How acting for the stage in Germany compares to acting in the United States

• What it looks like to overcome significant personal obstacles and stick it out against all odds

• How the art of acting compares to the art of working as a visual artist

• How to create a life as an actor and find a healthy balance between work and play

• Why it’s often a good idea to take a break from acting if you need to

But you’re not ready to take a break just yet. Let’s start with vocal training and see what that looks like for the actor in Los Angeles.

TRAINING YOUR VOICE FOR THE JOB

► An Interview With Bob Corff

Bob Corff has been working as a voice coach in Los Angeles for more than three decades. His film, television, and stage clients over the years have included Hank Azaria, Angela Bassett, Jason Bateman, Don Cheadle, Toni Collette, Jesse Eisenberg, Sally Field, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Samuel L. Jackson, Anna Kendrick, Jennifer Lawrence, Andie Macdowell, Ewan McGregor, Julianne Moore, Olivia Munn, Gwyneth Paltrow, Vanessa Redgrave, John C. Reilly, J.K. Simmons, Emma Stone, and Channing Tatum, to name a few. (For a complete list, visit Corff’s website at http://www.corffvoice.com.)

Bob Corff

I’m worried you’re evaluating my voice.

I know. I’m off duty, though—just here to serve.

So you work more with screen actors than theater actors, but you have a background in theater yourself, right?

Right. I’m old enough that I trained and then starred in three Broadway shows before I got into coaching, so I got my beginning on Broadway—I learned how to fill a house.

Could you tell me a little about your path to this career, your background?

Basically, I graduated from high school and decided that being in a rock band would be a good idea, so I put together a couple of musician friends, and we had one rehearsal and opened at a gas station. And as fate would have it, somebody from MGM records came in to get gas and found us. So I started as a lead singer in a rock group called “The Purple Gang.” That was the first taste of show business for me. I’d started taking voice lessons as soon as I thought about being an actor or a singer, because in those days, that’s what everybody did. I didn’t know anybody who didn’t do acting class, dance class, and voice class.

When was that?

Oh, this is back in the late ’60s. So I’ve seen how things have changed. Then, after I was in the rock band, I auditioned and got the lead in Hair. I took over for Jimmy Rado, who was the original star of it, and I did that for 11 months.

And this is important in terms of what we’re discussing here. Tom O’Horgan was the director, and after the first night of my doing a show, Tom said to me, “You know, in the second act, your voice needs to be much bigger. You need to fill the theater.” And I remember thinking to myself, this is a lot of intimate stuff going on with this character, and it felt really wrong to be talking so loud. But what I love about myself looking back was that I was smart enough to know that I didn’t want to lose that job. So I just talked really loud during the second act.

And I’ll tell you, it really didn’t feel good to me. And every night, Tom would come back and go, “Great!” And about the third night, it stopped feeling so weird. And then I just realized that to do a good job in the second act, it took that much vocal energy, and then it stopped feeling uncomfortable.

So it was just the newness of using your voice in that way.

It was. So what happens to a lot of people is that when you learn voice or some new technique, it’s uncomfortable in the beginning because it’s not natural. But the people who are successful are the ones who are willing to go through this discomfort to get to the place where it finally relaxes and they can say, oh, this is now my instrument.

Were you concerned that you looked like a bad actor in that second act? I imagine to some degree it’s a matter of trusting the director.

Well, I trusted him because I didn’t want to lose the job, and he was a famous director. And really, as smart as I thought I was at that age, I thought maybe he was smarter. But what I do with my clients now is, I tape the lessons—or now we’re using smartphones. So I say, “Now, you know that part where it felt really uncomfortable—too big, too loud, too exaggerated? Let’s listen to it.” And they’re always shocked and surprised, because it’s not. It’s just that if you have a very soft voice and then you start to talk a bit louder, it feels like you’re yelling, but you’re not.

And the more you talk at that volume, the more natural it feels?

Yes, but it can take many, many hours of that before it feels natural. I’ve had a chance to work with a lot of stars, and one of the things I admire and enjoy about working with those kinds of people is how hard they’re willing to work—how willing they are to do whatever it takes to get the result. I’ve had people who have said, “You know, I worked eleven hours on this yesterday,” and I would think, wow, I wouldn’t have the courage to tell them to practice eleven hours. But they did whatever it took so they could break through.

I think people sometimes attribute an artist’s success to luck or connections or something outside of his or her control.

No. People who are very successful work very, very hard—harder than you think. It’s not like, oh, I kind of would maybe like this to happen in my career. No. It’s, in two weeks I’ll be making a film that people can see for 100 years. Or in two weeks I’m going to be on stage in London. I’d better get my voice handled. So it’s real for them. They have to get it done, and they’re willing to do whatever it takes. So it’s rewarding for me, obviously, to work with people whose commitment is that complete.

What about talent? Are there some people who are just more talented, more capable of getting the accent, or getting rid of the accent? How do you tackle that?

The answer to the question is, yes, some people are more gifted. Being a singer, I think that’s why I was able to do accents—because I heard the melody, the stresses, the placement—so it was just a little song to me, that accent, so that was my way in. There are some people who have very good ears, and they’re quick to pick things up. But I’ve worked with really big stars who didn’t have that natural talent for accents. And for them, it was hard. It was just bone-crunching hard work, but they got it anyway because they did the work.

But yes, clearly some people get it more easily. That’s the first thing that everybody wants to know—how many lessons will it take? And I say, well, I would love to tell you, but if anybody tells you that they’re just making it up. I can give you an idea. It could be a couple lessons, or it could take you a couple of months. It depends how quickly you pick it up, how hard you work, and your commitment to consistency, doing it day after day.

Daily—and what about during the day in the actor’s real life? Do you recommend that actors practice the accent, incorporating it into their routine?

I do. It’s very hard for a lot of people to do it 100 percent of the time. I’ve had people who went in, auditioned with that accent, did the movie for three months, and when they finished the picture, they talked to that producer with their original accent and blew their minds. That’s an extreme case, but I would say that you should go to restaurants where you don’t know the waiter, in the taxi, or in the market where it doesn’t matter. Always do it there first, because you want to do it in a safe place before you start doing it in auditions or when you’re shooting or in rehearsal.

Is it always a matter of hard work then? Have you never come across an actor who simply wasn’t able to get a certain accent or get comfortable speaking loudly?

I have a sign next to my piano in my studio that says, “Change is possible.” A lot of people just think, hey, this is my voice. My shoe size is nine, and that’s not going to change. But your voice is a matter of muscle and coordination, so you can change your voice. But you have to believe it, because if you’re sure it can’t change, then you’ll be right.

What would you say are the most intimidating vocal problems for an actor to tackle?

I think it’s just confronting the sound of your own voice. People feel very uncomfortable when they listen back to their voice for the first time. The reason you’re uncomfortable is that when you talk, not only are you hearing your voice with your ears, but you’re hearing it bouncing around inside your own head, so it seems much more resonant and big inside your head. And then when you hear it played back, you’re just hearing it with your ears, which is how everybody else hears it. It can be uncomfortable at first, but you need to hear it.

You can’t fix something unless you can confront what’s really there. So that’s why I tell them, you’ve got to listen for these things. You will get better. But you’ve got to be willing to not be good for a while—that’s what it takes to become good.

I like that, “you’ve got to be willing to not be good for a while.”

I’m jumping off track a bit maybe, but as a personal side note—I have a friend who is a very successful screenwriter and then became a director, and we were having lunch years ago, and I said to him, “Don’t you think we’ve been lucky that we’ve done so well in our careers?” And he said, “Lucky? I wrote bad scripts for ten years before somebody finally hired me. I did my homework, and so did you.”

That’s how people become good. Every once in a while somebody gets something on no work. It’s like going to Vegas and putting in a quarter and winning $1 million, and then 20 million people come and lose. So it can make you think, maybe if somebody did it with no work, I can, too—but that very seldom ever happens.

Sure, and then where do you go from there? At some point—soon—you’re confronted with work!

Exactly. It’s a myth, that.

I’d love to talk more about the most common vocal problems and how to tackle them. So learning to deal with the sound of your own voice. What else?

I would say the thing I see most often now is that people don’t breathe properly. The voice is all about how you handle and organize and send your air out of you. So when people don’t breathe properly, the voice is weak—you can’t get it to go where you want it to go. And because there’s so much pressure today, more than ever, our stomachs are all locked up—beyond the fact that we want to look good and hold our stomach in! I find that’s pretty universal nowadays.

But when people start to breathe properly, it’s better for their health, too—because all of a sudden they feel better, they have oxygen and blood flowing in their system the way it’s supposed to, as opposed to being tight and living in a position of “I’m ready for the hit” all the time. That’s what happens, the stomach locks up like it’s ready for an attack, which isn’t a good position for art or life.

Do you think there’s any correlation between emotional stressors—or even personality temperaments—and the way actors speak or are able to speak?

Absolutely, and yet, there are people in show business who are very successful who are tense and crazy as a loon, but they have an instrument that works for them, so their voice can be good even when they’re not good. That’s what technique is for. It’s not for the days that you’re inspired, because those days you don’t need anybody. Those days, it’s all, “I’m flowing today—my choices are good, my voice is open.” But that doesn’t happen every day no matter who you are. So if you have an instrument that knows how to do its job, then when you open your mouth, out comes this big sound, and you go, “Oh, I’m here.” It grounds you, and then you can do your job.

If you were working with an actor who’s just about to showcase for agents, perhaps at the end of an MFA program, what kind of advice would you have for that actor?

Well, you only have two things to work with on a physical level—you have your body and your voice. People work on their bodies all the time—they go to the gym and dermatologists, they get their hair done. They do all kinds of things to get themselves looking as good as possible. But so often, they don’t do the work on the voice. And as a director friend of mine said a few years ago, your voice is your other face. It’s your instrument, and you need to train it to be capable of doing what your impulse wants to do as an actor. In the same way that your body can make someone take notice, can get you in the door, your vocal instrument can make the difference between getting the job and not getting the job. And when it’s working for you, that can make you feel strong and powerful—you know that you’ve done your work, and it showed up for you.

Do you have clients who are screen actors and then they transition because they have a theater gig?

I have that all the time. I have big stars who go to Broadway, London, or somewhere for a show. They have three months, and they panic and go, “I’ve never done theater!” So they have to come and really do some quick work to get that instrument working. Because if your body isn’t used to talking loud for two hours, your voice will go out. You’ll lose it.

You’ve been doing this a long time. Have you found over the years any analogies between being successful in your career and how you’re able to use and manipulate your voice?

Absolutely. Today more than ever—it’s always been true, but today especially—young people don’t want to be uncool. Really at any age. And one way to prove that you’re cool—as opposed to uncool—is to speak with everything on one level. [mimics] “See, I’m just not going to get too excited about anything, because that really shows weakness, I think. So I won’t show too much nuance. Just keep it flat and cool.”

But you’ve got to give of yourself. I say to my clients, your job is to wake people up, to excite them about whatever it is you’re talking about. Otherwise, they’ll give the part to somebody who is interesting to be around. You may think you sound cool, but you sound like you’re putting it on. You have to believe that. We see right through it. The best storytellers make you feel like you’re there. The best actors take you on a journey from their experience. They’re using their instrument to take you on that ride.

By the way …

Bob says there are two keys for actors who want to make their voice work for them: articulation and resonance.

Articulation

“You have to be clean and clear so people can understand you. You don’t want to be over-articulate, because we don’t speak that way anymore. But if I don’t understand you, I tune you out—and, before that, I get frustrated. So you have to think, as an actor, is that something you want to do? Frustrate your audience? Force them to tune you out?”

Resonance

“When your voice is anchored into your body, then your body resonates and you vibrate. What happens is, you’re using your body, it resonates you, and then it resonates the room, and people in the room become resonated. They go, you know what? I like him. They don’t know why. But they’re tuning in to you because they see you, hear you, and feel you—and those are the things you get when you tune up your instrument, your voice.”

What about casting directors? Do you think they’re tuned in to why they like a particular actor—that the actor’s voice might have something to do with it?

There are some casting directors who have no sense of that, and there are others who, if your voice isn’t good, they say, go to Bob, go to him right away. Some people are very voice aware and some aren’t—but either way, if your instrument is good, they’ll be getting a better you.

What I do is really kind of a secret. There aren’t very many actors who are that aware about voice anymore, but there are enough of them to keep me and my wife very busy. Most people don’t have the benefit of an instrument that works for them—and the ones who do, they do much better and feel better about themselves.

Bob’s wife Claire began as an apprentice to Bob and has since become a renowned dialect coach herself. She teaches private lessons at Corff Voice Studios and accent reduction classes at the Strasberg Institute, and she continues to develop audio accent courses with Bob.

Claire and Bob Corff Voice

Studio, Los Angeles

I wonder if there’s a correlation between that human instinct to fight against change or the willingness to embrace change as a means to success. Yes? No?

Yes, absolutely. I have such great respect for schoolteachers, because people come to me, they pay me good money, and they say they want me to help them, and then they resist anyway—because that’s what humans do. So when teachers are working with people who don’t even want to be there, that must be horrifying.

But I’m lucky. People at least—even though they’re resisting—they’re still trying. They’re showing up and doing the work. We’re in a process. We come, we work, we fight a little against change, because nature isn’t happy when things change. But the people who are brave and strong and successful are the ones who are willing to move through that discomfort.

When I think of stage acting and voice, I think of that “actor’s voice”—do you know what I mean? Seems like that might be different from what you’re teaching, though.

Look, you can go too far with just about anything. You might sometimes meet a stage actor who says, [mimics voice] “Hello, it’s so nice to meet you”—and you know instantly that you’re in the presence of an “actor.” But nobody talks like that anymore, unless you’re playing a character like that. So I’m not teaching that, but it was definitely the vocal style at one time.

Do some voice instructors still teach this, though? The actor’s voice?

Well, there’s a wonderful woman, Edith Skinner—she’s got a very famous book, Speak With Distinction. And she was a great, great teacher, but she was a great teacher in the 1930s and ’40s and ’50s. And listen, I have great respect for her. The material is great. It’s just that nobody talks like that anymore—that was the way they spoke in the studio days. It’s called the mid-Atlantic accent. It’s in the middle of the ocean—not American. We have achieved a standard American accent now. In my programs, we have a lot of the same kind of exercises, but just with the pronunciation that people use today.

The thing is, you want to bring your voice up to the level of excellence, not excess. In this town, I’ve been doing it for thirty-five years now, and just about everybody knows who I am because I’m teaching what gets people jobs. A lot of voice teachers will teach you their “gift.” They have this big bass baritone body, and they always had that voice. I’m a tenor, so any bottom I have in my voice I had to put there. But no, if you sound phony and exaggerated, that’s not going to get you the job. That’s not what we’re striving for.

Next steps for the young actor?

Having a good voice will be a benefit to you whether you do stage or film. I’ve worked with a lot of really good actors who talk very soft when they’re doing a film, but their instrument is choosing exactly what they want it to do. And if there’s a high emotional scene, the instrument will take care of it. And if they do a show on Broadway or in London, their instrument is prepared for that. Your voice will follow you—wherever you go.

ESSENTIAL KNOWLEDGE AND HABITS

► An Interview With Jordan Lund

Jordan Lund has been acting professionally since the 1980s. He has made more than eighty film and television appearances and performed in more than 150 plays. He has worked on Broadway, Off-Broadway, in regional theater, and with some of the best Los Angeles theaters, including the Ahmanson, Pacific Resident Theater, the Blank Theatre, and the Odyssey Theatre.

Jordan Lund

Photo by Alex Monti Fox

Lund received classical training at Carnegie-Mellon University and began his career on Broadway at the Belasco Theatre for the New York Shakespeare Festival, in Romeo and Juliet, As You Like It, and Macbeth, all directed by Estelle Parsons. His Off-Broadway credits include All’s Well That Ends Well, Measure For Measure, The Golem, Twelfth Night, and King John, all at the Delacorte Theatre in Central Park for the New York Shakespeare Festival. Also in New York, Lund was in Eric Bogosian’s I Saw the Seven Angels at the Kitchen.

Lund is an Associate Artist with the New American Theatre in Los Angeles, where he has appeared in or directed twenty-two plays since 1997. He has had roles in films such as The Bucket List, Doc Hollywood, Speed, American President, and The Rookie, and in television shows such as NYPD Blue, Cheers, Frasier, Firefly, LA Law, Law & Order, Star Trek DS9 & TNG, Enterprise, ER, Chicago Hope, and The Practice. He has been teaching acting in Los Angeles since 1999.

You’ve been doing this a long time. What advice do you have for the aspiring actor?

The biggest advice I would give young actors is to get more than just actor training. Get a real training in the world. Learn about things that are going to bring you depth as an actor and as an artist. If you’re just learning voice and speech and movement and dance and acting technique, you’re not going to have any opinions or attitudes about politics, or religion, or education, or family—the things that you develop as a human being when you’re out in the world.

Any thoughts on paying the bills while you’re trying to get work acting?

Yes, you’ve got to earn a living. I’ve had long stretches of my career where I would work, and then stretches where I wouldn’t have an acting job. So it’s a good idea to figure out how to bring in income when you’re not working on the stage. You should have skills that you develop outside of acting.

What about acting skills? What do you think is the most important skill for actors to acquire?

I’ve learned over the years that the most important thing an actor can master is relaxation. It’s what stands in the way of an actor having authentic human behavior on stage. The stories, the plays, the movies, the TV shows—everything we do is pretend. The only authentic part is what we bring in our emotional life to the role. The very best actors can access their own personal life in those parameters, and that’s when we see an authentic, emotional performance.

Emotional availability and emotional expression is a really important part to the early development of an actor. I’ve worked with people in their 40s and 50s who have had conservatory training, and they’ve been working professionally, and the assumption is that they have emotional availability and also the ability to express it freely. But they don’t always, and when they don’t, it’s because of tension and self-consciousness. It’s impossible to be completely vulnerable and intimate in a public place if you’re self-conscious and tension visits you. So the actor has to continue to work on the ability to relax and let the expression come through.

Is some of the tension that you’re referring to in auditions? How can actors master the art of relaxation during the auditioning process—especially when it’s a coveted or potentially career-changing role?

Part of mastering the audition is understanding that it’s not about being rejected. We all have this feeling that if we don’t get the part, they’re rejecting us. But that’s not what it’s about. If I’m going into an audition and there are three other people auditioning for the same role and none of them looks or seems exactly like me, we’re not really in competition with each other. If they cast the other person, is it a rejection of me or is it an acceptance of the other person?

I’ve never walked into an audition where the people doing the auditioning were repelled by me, where I walked in and they said, you’re just too ugly, or I hate your voice, or my God, this guy stinks. Nobody’s ever done that in an audition. What they’ve done is treat me mostly with respect. They usually show you respect because you have a craft and they want you to do the best work so that you might be the one they cast.

And the reason they do or don’t cast you can be arbitrary. Maybe it’s because I’m three inches taller than all the other leads, and they don’t want me to stick out in terms of height, so they need somebody shorter. There are so many reasons why they pick somebody, and I’ve never imagined that any of those reasons has been because they rejected me. Actors need to cut that word out of their vocabulary. They can’t think about rejection.

“I’ve learned over the years that the most important thing an actor can master is relaxation. It’s what stands in the way of an actor having authentic human behavior on stage.”

Do you have any examples of getting cast for an arbitrary reason?

I know for a fact that one job I got was completely arbitrary, a guest star on a show on ABC for one season. When I was in the audition, one of the executive producers was wearing a golf shirt with the name of a golf course that I had played in New Jersey, and I mentioned it. We had a five-minute conversation about our experiences on that particular golf course. I got offered the role, and my first day of work, I walked onto the set and the producer came over to me immediately to ask if I’d played any rounds recently.

What about trying to land a leading role? Does that have more to do with talent? Is that a less arbitrary decision in the casting?

When it comes to talent, so often what you’ll see with young people coming into the business is that they censor themselves, so they don’t have full control over their craft—and that’s when the people casting can’t see their talent. They think they have to be perfect, that they have to make themselves look perfect. And unfortunately, that’s always going to work against them. So what happens is, they edit themselves in their work, and they try to behave in a way that they think people want to see.

I always tell my students to think of it this way—it’s okay for the audience to see me at my worst. If I’m going to bring a real human life to light in my performance, it has to be someone who you can sit in the audience and recognize. But that only happens when you watch fallible human beings. So we have to be willing to show the sides of ourselves as actors that we’re not proud of. It’s something that actors should try to start to get in the habit of from the very beginning of the journey, a willingness to show the side of themselves that they’re not proud of. It’s that willingness that allows an actor’s talent to emerge.

Do you think we confuse the idea that the lead role in a play—or film or TV show—is a hero? So actors have a sense that they should portray the character in a heroic way?

Look, if all I wanted to do was show you the heroic side of a character, then I wouldn’t be doing my job. I’m not illuminating a life. So I have to be willing to reveal weakness. And I have to be willing to seek the dark side in myself, in my own personality. How else do you play Jack the Ripper, or any of the other sociopaths that we get to play? They’re the most fun characters, but if you’re just play acting, it’s never going to be as moving to the audience as if you find the ugliness in yourself to bring to that light.

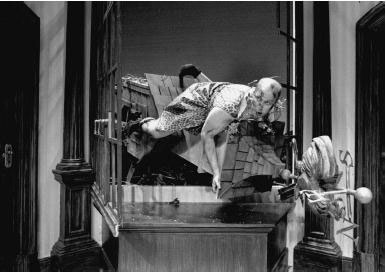

Jordan Lund as Sgt. Match in Joe Orton’s What the Butler Saw, Great Lakes Theater Festival, 1997

Photo by Roger Mastroianni

But being emotionally available is very different from being emotionally unstable. There used to be this idea that actors had to be unstable emotionally to be great artists. But actors shouldn’t be unstable emotionally. Actors should have psychological health so they’re able to go deep into themselves and utilize their emotional life without damaging themselves.

What about the aspiring actor who knows that he or she is emotionally unstable? Can a person with fragile mental health hope to succeed in this career?

Sure, some actors just need another outlet to learn how to express themselves honestly, and maybe that means a twelve-step program. Maybe it means a group therapy. Maybe it means talking to a clergy. Maybe it means talking to therapist. Any of those things are good. The key is to take care of yourself emotionally.

The Actors Fund

For information about counseling services for actors, visit the Actors Fund at http://www.actorsfund.org. Administered from offices in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago, the Actors Fund is a national, nonprofit organization serving all entertainment professionals through comprehensive services and programs. In addition to providing counseling, substance abuse, and mental health services, the fund provides emergency grants for essentials such as food, rent, and medical care. The Actors Fund was founded in 1882, serving performing arts and entertainment professionals in film, theater, television, music, opera, and dance.

How important are looks in this business? Does a serious actor pay attention to appearance?

If you want to spend time working out, getting healthy, doing your hair right, picking the right clothes, there’s nothing wrong with that. Beauty is prized in our business, so the better you look, the more opportunities you’re probably going to have. But you can’t do it at the expense of your emotional strength and life. And you can’t do it at the expense of your craft, doing the hard work of being an actor.

For so many people, fame has become an end result, a goal. I have plenty of contemporaries who have expressed that they would like to be successful as actors. But for most of them, the important thing was always to be an actor, to get the work. My contemporaries who I respect, if they could work all the time, that would be the greatest thing of all. It was never about being famous or looking perfect.

Every actor wants to get an agent. How do you advise your students about this?

Nobody gets an agent until they’re hip deep in it. But in the meantime, you send out emails to agencies with your picture and resume. Or you send out snail mail of flyers and postcards of shows you’re doing—try to get them to see shows. Also, there’s a new tool for marketing actors that hasn’t been around too long: casting director workshops. The only kind of workshop a casting director can conduct is one where there’s no promise of work, and very often they can’t even advertise where they work. But that can be a great way to introduce yourself and your work to people who are in the business of casting actors. And casting directors work with all the agents, so instead of contacting one agent at a time, this way you can talk to a casting director who has your back, and maybe he or she will introduce you to some people. The key is you have to be constantly proactive, either networking, seeking out representation or people to see you, self-generating work, doing scenes and monologues for classes, doing plays. If you’re in Los Angeles and New York, you should be auditioning constantly for plays and doing as many as you can, no matter what they pay you—and they probably mostly won’t pay you much.

“Beauty is prized in our business, so the better you look, the more opportunities you’re probably going to have. But you can’t do it at the expense of your emotional strength and life. And you can’t do it at the expense of your craft, doing the hard work of being an actor.”

Can anybody audition? If you move to New York or Los Angeles and you don’t have an agent yet, you can just audition for plays?

I’m not talking about Broadway plays. They’re little theaters. Some of them are under union supervision, some of them aren’t—but even the ones that are under union supervision are allowed to cast nonunion actors. Backstage also has auditions for plays at some of the little theaters around town, so on a weekly basis there are auditions available.

Also, in Los Angeles, there are about 200 membership theater companies. They all have websites with links to audition information. You join the company, and then they have to let you audition for plays. You pay your monthly dues. Some of them have meetings. Some of them you have to do other kind of work, like box office, or clean the bathrooms, or build the sets to donate hours for the company—and some of them don’t.

But that’s how actors without agents get considered for acting roles, and there are people who get them regularly through those vehicles. And sometimes you get lucky—you do a play, somebody else who’s in the play brought her agent that night, the agent sees you, and bingo, you meet an agent. There is no one way to do it.

Have you ever known that to happen?

Where someone’s agent first saw them on stage? Oh, yeah. I’ve known several people that’s happened to. That’s actually the best way. The agent was there for a client, but you knocked it out of the park that night.

Are there agents who only represent theater actors?

Agents don’t really do that anymore. But the opposite is true—there are agents who won’t represent actors for theater. Out here in LA, there are a lot of agents who will only represent actors for commercials, or on camera, or for voiceovers. They discourage their clients from auditioning for theater.

Because it doesn’t pay?

Right, and because LA theater is kind of the redheaded stepchild. At the Ahmanson Theatre and Mark Taper Forum, the contract has an eight-week out. Meaning, if I want to get out of the play, I have to give eight weeks’ notice. That’s pretty unrealistic, but its purpose is to discourage actors from looking for other work. Although it doesn’t stop people, and there are still plenty of people who work all the time in film and television during the day during performances of their shows. So no, if someone wants to just do theater, LA is the wrong place.

What are the options if you choose not to live in Los Angeles or New York?

Go to some of the smaller markets if you want to start a theater career. Markets like San Francisco, Seattle, Minneapolis, or Chicago—those markets have very vibrant theater scenes, and most of it is nonunion theater. A smaller market, or regional theater. That’s another real option for young actors coming out of school, to seek the regional theater life.

Should actors just starting out get headshots for theater work and different headshots for film and television work?

It’s all the same now. Everybody uses the same thing, a color headshot. And all you’ve got to do is go online. Every headshot photographer has a website. And everything is done digitally. Very few pictures are printed.

There’s so much rejection for actors. How can an actor know whether he or she has enough talent to pursue the career?

It’s an intangible. There is no way to know for sure. But you have to know that you’re enough. That’s another thing I try to impart to students all the time. You’re enough. No one is like you. Everybody is completely unique. So if you just simply exist honestly and authentically up there on that stage, then you will be perfectly you. When you try to start being somebody else, that’s when it gets cliché and no one wants to watch it.

Any final words of advice?

Don’t become complacent. It’s a real seduction to have an evening job, working at a restaurant or bar where you’re making some decent money and you have your friends. You’re going out drinking and partying, and all that fun stuff that actors do. And that’s important for actors to have fun. But if you’re doing that, don’t sleep until 3:00 pm and do nothing all day. You have to be proactive on a daily basis. Do something every day for your acting career, every single day. No matter what it is, do something. Maybe it’s a learning thing or a marketing thing, or maybe you’re working on a scene or monologue for a class.

You’re working in a solitary way so much of the time as an actor, so it’s a good idea to have a coach, or a friend to work with, or an acting class to go to. You want to make sure you have somebody to work off of when you’re practicing a monologue or preparing for an audition, so it’s not just a vacuum and you’re not relying only on your instincts. But you should always be learning. It takes a lot of work to be an actor, and it should be work. Any job that you succeed at, you put work into it. It doesn’t just happen.

THIS IS NOT MY BEAUTIFUL HOUSE!

A Semi-Imaginary Interview With Berliner Ensemble Actor Laura Tratnik

• By John Crutchfield

Setting: A two-bedroom flat in Berlin-Kreuzberg. Tastefully but minimally furnished w/beige couch, a few mismatched chairs, a bookshelf crammed with titles in English and German, plus an assortment of DVDs in no particular order. At one end of the couch LAURA, a svelte European woman in her early thirties, sits with her legs folded under her. At the other, JOHN, a somewhat scrawny American man in his mid-forties, sits with a laptop on his knees. For some reason, he wears an obviously fake black mustache. From OFF we hear the sound of a CHILD singing to herself—a bilingual mash-up of the Frozen soundtrack.

JOHN: [calling OFF] Polly? Could you sing a little more quietly, please? Mama and Daddy are working in here. [The singing continues unabated.] Okay. I guess we’ll have to deal.

LAURA: Um, can I ask you a question?

JOHN: Sure.

LAURA: What’s with the ’stache?

JOHN: I thought it would make things more objective.

LAURA: It’s weird.

JOHN: Exactly. A little Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt. In fact, for purposes of this interview, I’d like you to call me Klaus.

LAURA: Uh huh.

JOHN: But before we begin, I should say that this is for a chapter called “Sticking It Out.”

LAURA: Which means …?

JOHN: You know, keeping the dream alive, not giving up just because you haven’t had instant success right out of drama school. Which now that I think of it, doesn’t really apply to you.

LAURA: No.

JOHN: Okay, well, so you’re a counterexample. We can work with that. You graduated contract in hand. The Berliner Ensemble, no less. So: to what do you attribute your success, Ms. Tratnik?

LAURA: Right. Well, I would say that my success is due in large part to the reputation of my school.

JOHN: Ah! The Ernst Busch Academy of Dramatic Arts!

LAURA: That’s the one. It’s seen here as sort of the West Point of drama schools, where artistic directors from major houses all over Germany, Austria, and Switzerland scout new talent. I had several offers before I completed my studies.

JOHN: Amazing. But how did you end up there to begin with?

LAURA: Luck had a lot to do with it. In this profession, there’s always an element of luck and the magic of the moment. If you’re in good form on the day of an audition, then maybe, during those few brief minutes, you manage to concentrate and at the same time let go. Of course, I get nervous during auditions, but usually I’m pretty focused. My basic attitude is always, Now I’m gonna show you people! Probably because I found my way to theater by accident.

[From OFF, the CHILD sings, “Here I stand…”]

JOHN: [calling OFF] Uh, Polly? Maybe you want to go back into Mama and Daddy’s room to sing?

CHILD: [OFF] No!

JOHN: [to LAURA] Wait. You found theater by accident?

LAURA: I had an arts-based education in the Waldorf School, but I never thought about theater as a career. In fact, I came to Berlin to study Japanology at Humboldt University. And even that was really just an excuse to move to Berlin.

JOHN: Japanology?

LAURA: Yeah. “Japan” plus “ology.” “Japanology.” Maybe it’s a German thing. Anyway, one night I went down to Vienna for this art opening, and out of nowhere the gallerist tells me I have something special and I ought to apply to acting school. No one had ever said anything like that to me before, but somehow it resonated. So without telling anyone, I started preparing for an audition at Ernst Busch.

JOHN: Knowing that something like 2,000 people apply there every year? And they accept 15?

LAURA: Well, I figured I might as well go for the best. I had nothing to lose.

JOHN: And you think that attitude helped you?

LAURA: Absolutely. It made me more open and emotionally available. I mean, I’d worked really hard on my monologues, but my feeling walking in was like, Hey, let’s just go for it and see what happens.

JOHN: And …? What happened?

LAURA: Um, honey?

JOHN: Klaus!

LAURA: Your ’stache is coming off on that side.

JOHN: [investigates face] Oh. [Reattaches mustache.] Thanks.

LAURA: And I wonder if it’s really necessary? I mean, it makes you look like Kaiser Wilhelm II. After chemotherapy. Or maybe an institutional delousing.

JOHN: I think it’s working just fine. You were saying, Ms. Tratnik?

[A moment of indecipherable nonverbal communication between spouses.]

LAURA: [sighs] So I made the first cut and then the second cut—and with that I was an acting student.

JOHN: I see. And meanwhile, the other 1,985 people who’d been dreaming of this their whole lives and preparing for months and going without the refined pleasures of Japanology … What did they get? A set of steak knives?

LAURA: But that’s what I’m saying, “Klaus.” I think it actually helped me that I hadn’t been dreaming of it my whole life. I had other experiences. Even Japanology helped me somehow.

JOHN: So, what’s the upshot here? The way to become a successful actor is to not want to become a successful actor?

LAURA: Kind of.

JOHN: That’s totally Zen.

LAURA: Or is it fate? I mean, I’m here now, and certain factors led me here, a particular combination of talent, choice, luck, hard work, timing, circumstance. Take away one small thing, and the outcome would be totally different. Or would it?

JOHN: This is getting mystical. I don’t do mystical. No one named Klaus does mystical. Ever. Let’s get back to the facts. [Reads from computer screen.] “You’ve worked in both Europe and North America. How would you characterize the difference?”

LAURA: Well, certain things are the same everywhere—how people function together, the power structures and hierarchies. But there are differences that change the way you experience the work. What I love about working in the US is the concentration on the actor. Often, what the actor offers in rehearsal becomes the basis for the whole staging of the play.

JOHN: Are you suggesting, Ms. Tratnik, that actors are creative artists? Good God!

LAURA: They can be. And it has to do with curiosity. Not only curiosity about the world—history, politics, the arts, the natural sciences—although that is extremely important too. But also curiosity about oneself. A desire to find out things you don’t know, to break open your idea of who you are and look deeper. Your curiosity has to be stronger than your ego and your need for security. That’s why courage is so important for an actor.

JOHN: And you think American actors are strong in this way?

LAURA: Well, I think American culture encourages people to see themselves as creative, but it only goes so deep. When I watch American TV series or films, or go to see plays in the US, the actors often have this wonderful naturalness about them. But over time, you notice that this becomes a sort of habit. In a way, American actors mostly play themselves—which explains why they’re so good at it. Like even you, right now, you’re still just John.

JOHN: I beg your pardon. I am most certainly not “John.” Need I remind you that I have a mustache? And please consider my nervous tick. [does something with eyebrows] It’s a character choice.

LAURA: Except it’s the same character choice you make for every character I’ve ever seen you perform—and frankly, you do it at breakfast too.

JOHN: Have you never heard of the Method?

LAURA: Is this interview over yet?

JOHN: Far from it. You have yet to tell us anything about how the actor is viewed here in Europe.

LAURA: Well, the dominant principle here and in much of Europe is Regietheater, or director-centered theater. So the director is more the star than the actor. The stage actor’s purpose is really to bring about the director’s vision.

JOHN: Is there an actors’ union in Germany?

LAURA: No, so that’s another big difference. But really, the professional circumstances are difficult to compare. We have a lot of state-supported ensemble theaters, even in smaller cities, so working actors in Germany are more likely to be salaried than freelance. Which is nice, because it means you get to live and work in one place.

JOHN: Think of these American actors, where if you want a career you have to be completely flexible, traveling to jobs and living out of your suitcase for months on end. You come back home to your partner, and they’re like, “You talkin’ to me?” And then the mohawk. It gets ugly.

LAURA: True. Which is one reason so many artists end up together. It takes one to know one. The only problem then is that your partner is equally overworked and underpaid and torn between the limitless demands of art and life, and so who’s going to pay the utilities this month and who’s going to pick the kid up from day-care? “Oh shit, we have a kid?” And so on. Actually, artists should marry dentists.

JOHN: How long have you felt this way?

LAURA: But the whole cultural paradigm is different here. Being an artist in Germany actually confers a certain social status, even if you’re living hand to mouth. Artists are seen as doing something important in the culture. In the US, it’s more of an all-or-nothing view. Unless you make lots of money or get a zillion views on YouTube, no one seems particularly interested in whatever it is you’re doing with this so-called art thing. People look at you funny and assume it’s a cover for laziness or something illegal—which is pretty discouraging for the artists themselves. On the other hand, it can lead to a kind of solidarity and love of the work for its own sake. I mean, look at you guys at the Magnetic Theatre. You have this tiny space, and everybody has to have a day job, but you’ve got total artistic freedom. Sure, your annual budget wouldn’t pay Bob Wilson’s laundry bill, but at least it’s your own thing you’re doing, and you know the people you’re doing it for. And who knows where it might lead?

JOHN: You make poverty and despair sound so nice.

LAURA: And by the way: ’Stache Alert.

JOHN: Oh. Thanks. [investigates face, reattaches mustache] Can you tell us about your work at the Berliner Ensemble, Ms. Tratnik?

LAURA: Yeah, you know? This whole [air quotes] “interview” thing? What are you doing? This isn’t even me. These words aren’t even mine. If they were, they’d be in German. And worst of all—it’s not funny!

JOHN: Who said that was my artistic intention? Believe me, after living in Berlin for three years, I am so far beyond that, Ms. Tratnik. Oh, so very far. You have no idea. So maybe you could just get with the program here? Your work at the Berliner Ensemble?

[Another moment of indecipherable nonverbal etc.]

LAURA: The Berliner Ensemble is a repertory theater. Dozens of plays rotate through the schedule every season. Meanwhile, new productions are premiered, while older ones—or ones that aren’t doing well at the box—get retired. Certain productions are considered classics, though, and will play till doomsday: Tabori’s Waiting for Godot, Wilson’s The Three Penny Opera. This season, I’m in fifteen different plays, some supporting roles, some leads, and during the day I’m usually in rehearsal. But my schedule is extremely unpredictable, and it changes on short notice. The total hours per week range between thirty and ninety, depending—and is out of all proportion to the salary. The contract is officially year to year, but generally, if you do a good job, your contract gets renewed. So even though we don’t have a union, there’s some degree of security.

JOHN: [reading] “What would you say is the greatest professional challenge you’ve faced, and how did you …”

LAURA: Shhhhh!

JOHN: What?

[A faint sound from the next room. Matches being struck? Tissue paper being torn into interesting shapes?]

LAURA: [calling OFF] Polly?

CHILD: [OFF] Yes?

LAURA: [calling OFF] What are you doing?

CHILD: [OFF] I’m making myself beautiful!

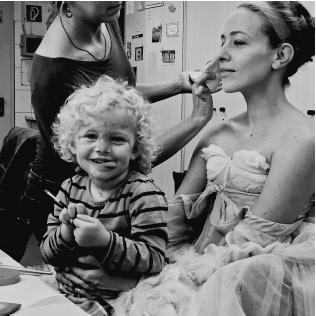

Theater makeup? That’s easy!

LAURA: Uh oh. [calling OFF] Like what exactly? I hope you’re not getting into my makeup …

[silence]

JOHN: [calling OFF] Polly, are you playing with Mama’s makeup?

CHILD: [OFF] No.

[beat]

LAURA: Is she lying?

JOHN: Does she even know you can do that?

[beat]

LAURA: My greatest challenge—staying true to myself. Going my own way, however difficult that is. Not becoming dependent on external circumstances or the demands or moods of directors and colleagues. In this profession, you have to preserve your inner equilibrium. You have to let yourself be challenged without losing your bearings on who you are. Only then are you able to do your best. Very rarely does everything just click from the start. Usually, you have to fight to be recognized in your full depth and complexity as a human being and an artist. This is extremely important early in your career, because it sets the tone for the kind of collaborator you’re going to be.

JOHN: [reading] “At one point, you took a break from your career, moved to the US, got married, and had a child. How did this experience change you?”

LAURA: It changed everything. I’m no longer constantly at war with myself. I have a healthy counterbalance to my professional life that puts a lot of things in perspective. At the same time, I’m less driven than I was before, and my need for peace and quiet is greater.

JOHN: So how do you manage career and family?

LAURA: Good question. During a big production last year, for instance, I realized at one point that for three weeks I hadn’t put my daughter to bed a single time. That made it clear to me that something had to change.

JOHN: I suspect you weren’t the only one who felt that way …

LAURA: No, “Klaus,” I don’t believe I was. And would you mind if I stuffed that mustache up your nostrils using my thumbs?

JOHN: [reading] “What advice would you give actors just starting out in their careers, especially those struggling to ‘make it’”?

LAURA: I’d remind them that life outside the theater is also important. In fact, it’s what we create out of, and it’s what we present on stage. Acting is the most beautiful job in the world, but it also eats its own young. The only way to survive is to be obstinate, and to do it for your own joy and satisfaction. Not to get famous. That’s mostly out of your control anyway. Better to love the work itself. Then if the big break happens and you get “discovered,” super—and if not, who cares? You still have this thing you love that you can keep doing. All you need is your own creativity and the respect of your collaborators. As long as you keep your spirits up and your love of the work alive, it will continue to give your life meaning. That’s what it means to have integrity as an artist.

JOHN: [reading] “Where do you see yourself in ten years?”

LAURA: Somewhere else. Earning more money, so that I can travel and have my own house and a garden. Doing artistic projects only if they make me happy and stimulate me and involve people I like.

JOHN: You’d walk away from your acting career?

LAURA: From the career, yes. From acting, from the art itself, no.

JOHN: [reading] “If you could go back to the day you graduated from acting school, what would you do differently?”

LAURA: Nothing.

JOHN: Nothing?

LAURA: Nope.

JOHN: Not even crash a few parties at the School of Dentistry?

[A side door bangs open: a small CHILD wobbles in on a pair of women’s high-heeled shoes, wearing a pink tutu turned inside-out and a small plastic crown. Dark red lipstick covers much of her face and arms.]

CHILD: Ta-da!

[Curtain]

Husband-and-wife team JOHN CRUTCHFIELD and LAURA TRATNIK currently make their home in Berlin, Germany, where Tratnik is a member of the Berliner Ensemble and Crutchfield teaches courses in creative writing and theater at the Freie Universität Berlin. He is also a Founding Member of the Magnetic Theatre in Asheville, North Carolina, where he continues to direct and perform original work, including, most recently, The Jacob Higginbotham Show. In addition to her acting work at the Berliner Ensemble, Tratnik has appeared in two of John’s plays, The Strange and Tragical Adventures of Pinocchio (Magnetic Theatre) and Come Thick Night: A Shakespearean Gruselkabinett (FringeNYC 2014), both of which Crutchfield also directed. More is sure to come.

John Crutchfield

Laura Tratnik

Photo by Lauren Abe (press photo for The Songs of Robert, 2007)

An Interview With Regan Linton

► By Jason Dorwart

Regan Linton is a professional stage and film actor. She uses a wheelchair due to a spinal cord injury from a car accident in college. In 2013, she graduated from the MFA Acting Program at University of California San Diego (UCSD) as the first wheelchair user to do so. Prior to graduate school, she worked for six years with Denver-based community theater companies and was honored with numerous awards for her performances, including the Colorado Theatre Guild Henry Award and Denver Post Ovation Award.

Regan Linton

Photo by Kathy Hollis Cooper

Can you tell me about yourself and your spinal cord injury?

Sure. I grew up playing sports and was very active. In undergrad, at University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles, I was in a car accident and came away with a T-4 complete spinal cord injury where I was paralyzed from my chest down. Basically, I have no sensation or movement below that, and I use a manual wheelchair. It definitely wasn’t something I ever planned, and it has changed my life in many ways—mostly for the better.

Did you have dreams of getting into acting before your spinal cord injury?

I did. I started performing when I was a kid. I took theater classes, acting classes. I was a shy, introverted, do-gooder child, and theater was the place I could act out and let that other side of me—the darker, angry side—come out. Theater was where I processed a lot of emotions as a kid. In high school, I had dreams of going to a major conservatory, but I didn’t get in. I went to film school and started doing other things.

What prompted you to start acting again?

Immediately after my injury, I was like, “There’s no possible way I’m ever going to perform again. How can I even do that?” All of a sudden having a two-thirds paralyzed body—in my mind, I couldn’t act without legs. I couldn’t act without full abdominal breath support. But I still had a passion for it. But afterward, I completely changed the way I thought about my body—and about my body on stage—and it reinvigorated my confidence that I could get on stage and do some acting.

At what point did you think to yourself, “I can make a living at this”?

I’m still trying to convince myself, but not because I’m an actor on wheels. It’s because that’s the way the actor life is. When I auditioned for the UCSD MFA program, the head of the program, Kyle Donnelly, asked me point blank in the audition, “Do you think you can work as a professional actor?” There was something inside me in that moment that thought, “Absolutely, yes. Of course I can.” The confidence I had gained competing city wide with other theater companies and being honored with a couple of local acting awards made me think, “Oh, I can do this! The only thing I’m lacking is professional training, technical training, and the experience of getting myself out there.”

Sometimes people attribute an artist’s success to connections or something outside of the artist’s own control. What is your take on that?

What is out of my control is how people are going to respond to me as an actor on wheels. Sometimes they think I’m very inspirational, and sometimes they’re amazed and don’t know how I do it. Sometimes they think I’m doing it as a character choice, and they don’t know I actually use a wheelchair full time. There are not a lot of professional actors out there with different physicalities and my level of training. I was looking into the possibility of grad school and found only a handful—five people—who use wheelchairs and had gone to school and trained.

“Oh, I can do this! The only thing I’m lacking is professional training, technical training, and the experience of getting myself out there.”

What would you say an actor can control?

The biggest thing actors can control is how they respond to feedback. The way you respond to the world is within your control. You have the choice in life to be like, “Okay, people have said no, and that means no, and therefore I’m not going to continue.” Or when you get rejected, you can say, “Well, screw that. I’m going to continue to improve and go forward.” It’s my inner competitive spirit to go against the lack of expectations people might have for me.

In your mind, what is the difference between talent and skill for an actor?

Oh, my! A skill is your toolbox. In grad school, that’s what I was gaining—tools to build skills. Repetition and experience are needed to build skill. It’s a trade. To do it well, you have to do something over and over again so it becomes part of you. But talent is sometimes an arbitrary concept. The greatest talent in acting is the willingness to be vulnerable. One of the things I had the ability to do partly because of my injury—which was also enhanced by my training—was just be. Just be on stage and be in the world.

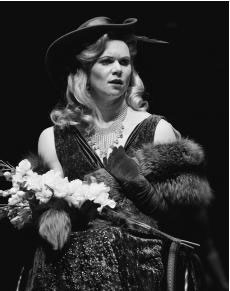

Regan Linton as Don John and Barret O’Brien as Borachio in Much Ado About Nothing, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, 2015, directed by Lileana Blain-Cruz

Photo by Jenny Graham, courtesy of Oregon Shakespeare Festival

At the end of its MFA program, UCSD has an actors’ showcase. What was your experience with that as an actor in a wheelchair?

It’s one of the most beneficial and absurd things all at the same time—to spend so much time preparing for the tiny amount of stage time you’re going to spend in front agents and managers. Part of me thought, “This is the most ridiculous thing.” It seems like such a silly blip on the radar, and yet I got a good agent out of it who has really been beneficial to me and has helped me grow in my professionalism.

For me, a lot of my time was spent educating the agents and managers: “Oh, this is my experience. Yes, I use a wheelchair. Yes, I can do things. I can get out of my wheelchair. I’m not glued to it.” Educating about larger disability things but also giving them an idea of what kind of an actor I was. There aren’t a lot of actors on wheels. Often, I go into an audition, and it’s like I’m not only proving my talents and worth and capability as an actor but also my worth as a human being—and even sometimes trying to prove that I should be alive.

How many meetings did you get compared to your classmates?

My response from showcase was much lower than most of my classmates. Maybe three agents total wanted to meet with me. Managers, I got one meeting. I have classmates who got responses from twenty managers in Los Angeles. I got a much a lower response. But that said, the response I did get was very genuine. Often, when they encounter actors, it’s like, “We don’t really know who this person is.” Maybe my authenticity was more on the surface, and the people who did meet with me were genuinely interested in me as an actor and not something superficial about my wheels and my physical persona.

I know you moved to Los Angeles and had auditions but weren’t getting a lot of work at first. What did you do to keep yourself in shape and mentally sharp before landing your first role?

I moved to Los Angeles in June. That timing was weird because of the casting cycle. Summertime is dead. I had a few hard months, even as we started moving into the fall when things start picking up again. They say in Los Angeles or New York, it takes at least three years to have people even be aware of you. That’s with having a really great agent or manager. Most people take a job—becoming a waiter or valet or something. Those jobs are very labor based and weren’t workable for me, so I struggled a lot with, “How do I keep myself engaged?”

I ended up doing small projects I got through grad school contacts. Then I did land a part on one show, but the show was cancelled three days later, so I never ended up filming that. So I stayed pretty regular with physical activities. I would swim and work out with a trainer, and I would try to do whatever I could to pick up side jobs. Eventually, I decided to write my own material. That ended up taking a good amount of my time when I was in Los Angeles. I wrote my own show for the Hollywood fringe and also worked on some web series ideas with friends. That was a lot of my daily work.

When you go to an audition, do casting directors know you’re in a wheelchair beforehand?

Yes, typically they do. My agent would make an extra phone call to say, “Hey, this is my client. She’s really a great actor, and by the way, she uses a wheelchair …” Most of the breakdowns that come out don’t mention a wheelchair, so the casting directors aren’t thinking of the possibility that a person on wheels could be in the role. When I’m presented to them, a lot of reactionary things go through their heads, “Would she survive on set? Can she work an eight-hour or ten-hour day? Does she need an accessible dressing room? Do we have that?”

It’s always helpful having an agent who has been in the business for a long time and has personal connections with the casting directors, because they respect her opinion. Often she’s the one who gets me in the door to a lot of auditions, because she’ll make a call. I put that I’m a wheelchair user on my resumé because I feel like, ultimately, they’re going to hire me or not hire me, and they’re going to have to know I use a wheelchair. I don’t really like the idea of surprising somebody by just rolling into the room. I realize my privilege of having an agent who’ll submit me and make that extra phone call to give a heads up.

Are there roles that you might resist taking because of how they portray disability?

Luckily, my agent has been pretty careful and approached me as an actor and not as a disability charity case. She knew I’m a diverse entity. I’m not a common entity, but she wasn’t ready to exploit that.

There was one breakdown in particular that read, “People with disabilities needed to sit around Jesus and accept his love,” or something like that. I used it as material in my Hollywood fringe show I wrote. I can often tell from the breakdown wording that it’s something I wouldn’t do. It’s a hard decision—many disabled characters portray the same storyline, but at the same time, it’s giving you stage time and visibility. There was a play I was offered about a young woman who had become paralyzed and how her family was dealing with it. It was the worst play I’ve read about disability. The playwright had taken every cliché about becoming paralyzed and everything sensational and shoved it together. That was a major playhouse, and I ended up turning it down because I felt, “This is not a story I want to be telling.” A lot of the people writing these roles aren’t writing from a disability perspective, and often they don’t feel complete to me. I would rather go for roles without disability written in and re-envision the role instead of playing these poorly crafted characters with a disability.

“I put that I’m a wheelchair user on my resumé because I feel like, ultimately, they’re going to hire me or not hire me, and they’re going to have to know I use a wheelchair. I don’t really like the idea of surprising somebody by just rolling into the room. I realize my privilege of having an agent who’ll submit me and make that extra phone call to give a heads up.”

Life is more expensive for disabled people. Is this accounted for in your contracts?

Life costs more because of my disability, no question, but I don’t get paid any more than other actors, so I end up absorbing the extra expense. I have to buy wheelchairs and pay for maintenance—casters, wheels, tubes, cushions. I’m using my own chairs during shows, so I have to buy supplies more frequently. And it’s a murky area as to who’s responsible for these expenses during the show. My chair could easily be considered a prop or costume, like someone’s shoes. But there are no guidelines I’ve found to help theaters clarify whether they should help with the expense. So yes, it definitely costs more to be an actor on wheels, but this isn’t accounted for in my salary.

When I was hired for an NBC show, they were trying to figure out whether I was going to need an accessible trailer. My agent intervened and advocated for me and said, “This is something you have to provide under the ADA regardless of whether it is an extra expense for you.” I also know for Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF), it was definitely a consideration. As a union actor on a ten-month contract, they’re required to provide housing. At the time I was hired, they had no wheelchair-accessible housing, so they ended up renovating a unit. From their perspective, because they’re a great theater company, they thought it was something they needed to do in general. If they renovated, it would be available for all of their actors, including a wheelchair-using actor.

When I don’t get a project, I don’t know whether it’s them thinking through the logistics of if I’m actually going to be able to get on stage, or is the dressing room accessible, or do they have an accessible actor apartment? I don’t know how much that factors in to their ultimate decision.

Have you had any issues with Actors’ Equity health insurance because of your pre-existing condition?

No. That’s one of the greatest benefits. In Los Angeles, I was without insurance. I’d gone off of my co-insurance, and Obamacare hadn’t started yet. I ended up using some free clinics. When I finally started at OSF, one of the best perks of being a union actor is the health insurance. It’s been wonderful. It’s really good health insurance. It’s difficult to keep, because you have to keep working—but for the time I’ve been on it, it’s been great.

Is there anything backstage that you need accommodation for, such as for quick changes or pants or specially constructed costumes?

It depends on the show, but in general, I’m able to do lot of my backstage work on my own. I do my own makeup. For one of the shows I was in at OSF, I did all my own costume changes. If I have a quick change, stuff is built with Velcro, or it would be laid over the top. For Much Ado About Nothing at OSF, there was a part where I put a dress on for a party. It was put over my fatigues, which was part of the design concept. But the dress only zipped from my torso up, so it didn’t actually go underneath my butt—but it looked like it did, so you couldn’t tell. That’s one adaptive accommodation. But I’m probably one of the least high-maintenance actors up there this year. One major accommodation at OSF—it’s a repertory theater, so they’re changing the set and putting different sets in and out. They built ramps for all of the entrances instead of stairs. But they’re beneficial! The entire crew uses those ramps for taking sets on and off stage. Really, it ends up being a universally accessible design for everybody. There are still definitely inaccessible things, but OSF is good about making accommodations whenever needed.

Regan Linton as the Mysterious Woman in Secret Love in Peach Blossom Land, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, 2015, written and directed by Stan Lai

Photo by Jenny Graham, courtesy of Oregon Shakespeare Festival

Advanced age and disability are often conflated. Have you found yourself reading for characters who are older than you because of your wheelchair?

Funny you should ask, because I was just asked to read for a project that I didn’t get—but I was asked to read for As You Like It, and it was an all-female production. The breakdown even said, “Somebody who should be able to read older.” I once played Ouiser Boudreaux in Steel Magnolias, who’s supposed to be like 50-plus years old. I don’t necessarily mind that. I love those roles. As a female, those are the roles I gravitate toward anyway—they’re the wiser, more experienced, more messy roles. I like that I fit into those maybe more than I would without my wheelchair.

But you’re right—there’s a lack of awareness of the fact that somebody can be young and vibrant and capable and productive and also have a different ability. Even with Much Ado this year, the particular take on my character, Don John—she’s the villain, and the take on her was that she had been injured in battle and is a veteran coming back. There are certain storylines that tend to pop up, because it’s what the public is aware of when it comes to disability—and often that’s an injured veteran or somebody who is indigent. We rarely see the storyline of somebody young and living their life and working and raising a family or those types of progressive storyline.

Now that you’re actually working, what’s your daily routine? Do you have time for training or skill maintenance while rehearsing and performing?

The rep acting lifestyle is pretty intense. It doesn’t sound like it’s going to be when you hear that you’ll have six shows a week. Initially it didn’t sound to me like it would be that taxing, and I thought, “Oh, I’ll have plenty of time for doing side gigs.”

The most difficult part is that your schedule is so irregular. You can’t say, “Okay, every night I’m going to have a show at 8:00 pm, and therefore I can set up my day. It’s like one night you’ll have a show at 8:00 pm, and then the next day you have a double. Then the next day you’re off, and the next day you have a matinee. The irregularity makes it really difficult to establish a routine, whether it’s exercise or physical therapy.

My daily routine often involves one show a day, maybe teaching a workshop or doing a discussion, training, or doing physical therapy. Then also, because I’m this unique actor entity, I’m frequently contacted by people from all over for articles or school papers, so often I’m doing that kind of advocacy or education work as well.

Any advice for the actor who’s really struggling to break in?

Oh, my word. You mean any general actor, not an actor with a different physicality? Really, it’s all the same. I’ve discovered—and you often hear it—“If you’re doing good work, people are going to hear about it. If you’re focused on what really, truly matters to you, then the rest will come. The success will come.” I know that can seem like a load of jargon, but I truly believe it. I think I’ve been a more effective actor post-injury. Not because I’m a unique entity, but because I have a better sense of self and of the stories I’m really passionate about telling, the places I’m passionate about working, the places I feel like I fit.

How do you get away from going through the motions and being this kind of empty vessel?

It’s weird, because that’s what we are. We’re an instrument—a vessel for other characters to flow through. Experience is great, but at some point, pull back and ask, “Okay, what really matters to me?” If you want to be a Shakespeare actor, don’t waste your time doing stuff that doesn’t apply. If you want to be part of Cirque du Soleil, go up to Canada and bang on the door until they let you in. Don’t stop learning and dreaming and believing you still have something more to learn or gain from people from all different experience levels or ages. I feel like the most beneficial thing I’ve held onto is probably that thirst for still being curious at all points of the game.

JASON DORWART is a PhD candidate at the University of California, San Diego where he is researching performances by and about people with disabilities. He is also a standup comedian and was a recurring company member of the Nebraska Shakespeare Festival. His work has previously appeared in TheatreForum. With his wife, Laura, Dorwart is editing a forthcoming anthology entitled mad/crip/sex. Dorwart’s assistant directing credits include A Play on Two Chairs (University of Colorado), Narnia (CenterStage), and As You Like It (Nebraska Shakespeare Festival). He holds a BFA in Theatre from Creighton University, an MA in Theatre from the University of Colorado, and a JD from the University of Denver.

Jason Dorwart

Photo by Chris Dorwart

A DIALOGUE ABOUT THE ART OF WORKING AS AN ACTOR

► By Kate Kramer and Elizabeth Stevens

Elizabeth and I met in the spring of 2012 when we became neighbors in West Philadelphia. Our friendship quickly developed when we discovered that we shared common ground in the arts and in higher education. We’re both educators and scholars, and both artists—I’m in fine arts and Elizabeth is on the stage.

As we’ve been at this game of working and living and teaching in the arts for a combined forty years now, we’re intimately familiar with the struggle and exhilaration of what it takes to “make it” in the arts. We welcome this opportunity to share our insights and concerns about the complexities of the artistic journey.

Kate: In the arts, I encourage artists to pursue work at whatever pace they can manage. In the juried situation, artists have a lot of work to do once they’re selected. They have to make the art for the exhibition, to get physical work ready for the show itself, and sometimes to build crates for shipping. A calendar of submissions and activities can help them keep track of submissions and the work required to fulfill their commitments or upcoming opportunities. Are there similar cycles in theater and auditions, or similar seasons?

Elizabeth: Hmmm … not exactly. Casting for plays can happen months, or even sometimes years, before the play, depending on the project and the kind of theater. And those things happen all the time. The good thing is that most actors and artists already know that they need to work their butts off. We’re told over and over that if you’re not working or trying to work all the time, if you’re not making drastic sacrifices, you’ll never make it. So actors and artists don’t really need to hear that they need to work hard, because they already know it. All of the auditioning can be exhausting.

Kate: Right! I think every successful artist I know is a work-a-holic. And by “successful” I mean someone who is doing the craft, involved in making.

Elizabeth: I think actors and artists might need to hear the flipside of this: You need to take care of yourself and have a life. Actors tend to audition for everything without discernment. And it’s hard to go to auditions and have a day job. Careers require making priorities, so the things you really care about auditioning for, the people you really want to work with, these are the things you should make sacrifices for—like asking for time off of work, or not hanging out with your friends, or missing that trip you’ve been planning for a while. But I think going to every single audition, which some people recommend—while it does give you practice in auditioning and in getting used to the constant “no”s—it isn’t sustainable forever. And it’s probably not how you’re going to get work.

Kate: Will actors find their people, their peers, at these auditions? Will they make connections with actors as well as casting agents, casting directors, or directors?

Elizabeth: Not really. The audition situation necessarily puts the actors in an unequal status relationship with the rest of the team. A big casting call is typically a table of people who are watching and judging you for about two minutes and then dismissing you. And while it might possibly be a chance to get your foot in the door, it’s downright demoralizing if it’s the only thing you’re doing to get work.

Kate: It sounds completely alienating.