Introduction

The traditional world of project management belongs to yesterday. There will continue to be applications for which the traditional linear models we grew up with are appropriate, but as our profession matures we have discovered a whole new set of applications for which traditional project management (TPM) models are totally inappropriate. The majority of contemporary projects do not meet the conditions needed for using TPM models. The primary reason is the difficulty in specifying complete requirements at the beginning of the project. That difficulty arises from constant change, unclear business objectives, actions of competitors, and other factors.

Not having a complete and defined set of requirements precludes generating a complete work breakdown structure (WBS), required by all TPM models. Most observers would agree that except for the simplest of projects, it is not possible to specify complete requirements at the start of a project. Even if you could, one could easily argue that the world doesn’t stand still just because you are managing a project. Changes in business conditions, the competition, and technology all can and do render requirements incomplete or at least misguided. The contemporary business climate is one of unbridled change and speed. Requirements are never really established; they continue to change throughout the life of the project. Cyclical and recursive models are coming into vogue; yet, many organizations continue to try to fit square pegs into round holes. How foolish, and what a waste of time and money. The paradigm must shift, and any company that doesn’t embrace that shift is sure to be lost in the rush. Alan Deutschman’s axiom “change or die” was never truer than it is in today’s project-management environment.1

1 Alan Deutschman, Change or Die: The Three Keys to Change at Work and in Life (New York: HarperBusiness, 2007).

The Contemporary Project Landscape

Change is constant and unpredictable! That comes as no surprise to anyone. In fact, change itself is changing at an accelerating pace. That should come as no surprise to anyone either. Yesterday’s practices belong to yesterday. Today is a new day with new challenges. All project managers, whether the most senior or simply the “wannabes,” are challenged to think about how to effectively adapt their approaches to managing projects rather than routinely follow yesterday’s recipe.

There is a great deal of uncertainty on the road to breakthrough performance. Success will not come unless accompanied by courage, creativity, and flexibility. If we simply rely on the routine application of an off-the-shelf methodology, failure is very likely. As you will see in the pages that follow, I am not afraid to step outside the box and perhaps take you outside of your comfort zone. I am going to stretch your thinking about how to deliver effective project management, and hence deliver expected business value.

Nowhere is there more need for change than in the approaches you take to managing the class of project whose solution is not clearly defined or whose goal is only vaguely defined. These projects occur often, and most often do not fit your current practices. Anecdotal data I have collected from my world travels suggest that at least 70 percent of all projects do not fit the traditional, linear project-management life cycle that we have grown up with. A challenge has been issued to all of us. That challenge is to align our project-management processes and techniques with the changing needs of the project, your business environment, and the markets you serve—or risk being dismissed as irrelevant. That means we must embrace change in our approaches and models, as well as develop models that embrace change. The goal of this book is to introduce a new approach to managing projects—one that rises to these challenges. I call this approach the Adaptive Project Framework (APF).

The initial version of APF was developed as part of two separate engagements with my clients. Neither of these was a software-development project. In one engagement, the client required development of a project-management life cycle (PMLC) that was fully integrated into a systems-development life cycle (SDLC). The other engagement was to design a kiosk application for a large supermarket chain. So, one project involved business process design, while the other involved new-product development. APF can be applied to both types. That sets APF apart from most of the Agile approaches, which are designed around software-development projects. I’ll have more to say on both of these engagements as two of the four case studies used in this book.

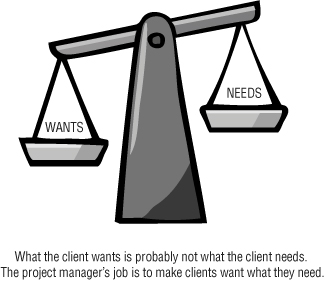

Buried beneath the mysticism that surrounds the technology revolution, a problem has surfaced. Businesspersons have an insatiable appetite to have their wants met. Sounds good so far, and no one would deny them that right. Surely technology could come to their rescue and help them get what they wanted. However, I have learned that wants are often the clients’ expression of what they think is a solution to some unstated or poorly defined problem they face. If we are lucky and their wants accurately reflect the solution to their problem, then the direction of the project is clear. But wants don’t often align with needs. Therefore, if you focus on satisfying wants, you may be focusing your attention in the wrong place and courting possible failure. Behind those wants are the true needs, which are often not stated. The businessperson has not distinguished between wants and needs; in fact, the wants have gotten in the way of seeing the real needs. This is not a matter of prioritization. It is a lack of understanding of the problem. This situation has persisted from the beginning of the technology revolution to this day.

If you remember anything from this introduction, remember the message conveyed in Figure I.1: that what the client wants is probably not what the client needs. If you blindly accept what clients say they want and proceed with a project on that basis, both you and the clients may be in for a rude awakening. You will have built something the clients cannot use. Often in the process of building the solution, the clients learn that what they need is not the same as what they say they wanted. Here we have the basis for rolling deadlines, scope creep, and an endless trail of changes, reworks, over-budget situations, and schedule slippages. TPM has to strain to keep up with the realities of projects such as these. A lot of time is wasted planning things that never happen. It’s no wonder that more than 65 percent of projects fail. That has to stop.

We need two things. The first is a process for discovering the needs that underlie the wants. Continuously asking “why” questions can uncover needs. I use Root Cause Analysis almost exclusively to peel away the wants and get to the real needs. Second, we need an approach that is built around change—one that embraces learning and discovery throughout the project life cycle. The approach must recognize that change will occur regardless of our attempts to the contrary. Our approach must have built-in processes to accommodate the changes that result from the learning and discovery that will certainly take place during execution of the project.

This book introduces a model that was designed precisely to accommodate these requirements. APF is that model. The name APF was carefully chosen.

Adaptive

From its very beginning to its very end, APF is designed to continuously adapt to the changing situation of a project. A change in the understanding of the solution might prompt a change in the way the project is managed, or in the very approach being used. Learning and discovery in the early cycles may lead to a change in the approach taken. For example, starting with an APF approach, you quickly discover the complete solution from the first few cycles of the project plan. Should you continue to use APF? Maybe some other Agile Project Management (APM) model would now fit better, or you might consider switching to some form of TPM, say an incremental approach. The new characteristics of the project will be the basis for any change of approach.

Nothing in APF is fixed. Every part of it is variable, and it constantly adjusts to the characteristics of the project. The changes in APF are not taken from a predefined list of possible changes. The changes in approach are a creative response to the changing needs of the situation. Obviously, APF requires meaningful involvement of the client and the project team, acting in an open and trusting partnership. Anything short of that will invite failure. To be successful with APF, you have to think like a chef and not like a cook! The cook can only follow recipes, and if an ingredient is missing, may be at a loss as to how to continue. A chef, on the other hand, has the skills and experiences to adapt to the situation and create recipes that work within the constraints of available ingredients.

My girlfriend provides an excellent example of what I mean. She makes a cheesecake that is to die for. Late one Sunday evening, she asked whether I would like her to bake a cheesecake for us. That’s a no-brainer for me, and so I said “you bet.” A few minutes after she started, I heard some rummaging around in the cupboards, followed by a moan from the kitchen. There was no vanilla extract, and that was an essential ingredient of her recipe. It was too late to go to the market, so I suggested she put the batter in the fridge and we’d pick up the vanilla extract in the morning. A few minutes later, I could smell a cheesecake in the oven. Maybe she had found the vanilla extract? No she hadn’t. Instead, she found a container of vanilla frosting, and vanilla extract was one of its main ingredients. She figured out how much vanilla frosting would equal the vanilla extract called for in the cheesecake recipe and used that instead. The cheesecake was awesome! So what does this have to do with project management? My point is that if all you can do is blindly follow someone else’s recipe for managing a project, you won’t have a chance. But if you can create a recipe adapted to the conditions of the moment, you will have planted the seeds of success.

Project

Projects are unique, and are never repeated under the same set of circumstances. So why isn’t our approach to managing them unique as well? I’m not advocating a wholesale change in management approach, but rather a thought-out approach—one that takes into account and deals with the vagaries of the project. There are project, organizational, and environmental characteristics to account for in choosing the best-fit project management approach. Among the characteristics I have encountered, the following arise frequently, and their impacts must be considered in your final decision as to the best-fit approach:

• Risk

• Cost

• Duration

• Complexity

• Market Stability

• Business Value

• Technology Used

• Business Climate

• Client Involvement

• Goal and Solution Clarity

• Number of Departments Affected

• Organizational Environment

• Team Skills and Competencies

• Completeness of Requirements

• Project Manager and Team Member Availability

Any combination of these project characteristics can cause a change in how the project is approached. For example, if a project approach requires heavy client involvement and you know from experience with this client that that won’t happen on this project, then you wouldn’t choose that approach. That may mean you have to compromise and choose a less-than-ideal approach to work around lack of meaningful client involvement. (Chaos Report 20072 lists, for the very first time, lack of meaningful client involvement as the number-one reason why projects fail.) Alternatively, you might build in a workshop on client involvement, and based on the results of the workshop make your decision on which project-management approach to use.

2 Standish Group, Chaos Report 2007: The Laws of CHAOS (Boston: Standish Group International, 2007).

As another example, suppose your organizational environment is characterized by frequent reorganization and realignment of roles and responsibilities. In such an environment, sponsorship and priorities of active projects will change. Your best-fit project management approach should be one in which deliverables are introduced in increments or short intervals rather than all-at-once at the end of a long project. Such a strategy will reduce the risk of wasted resources and loss of business value due to early termination of the project. I’ll return to this discussion in Chapter 9: APF Frequently Asked Questions.

Framework

APF has several variations. I compare it to following a recipe versus creating a recipe. TPM follows recipes. APF follows a framework. The TPM project manager needs to know how to follow a step-by-step task list with little thought of why. The TPM project manager is, in a certain sense, captive to the accompanying project-management approach. APF, on the other hand, creates recipes. APF project managers need to understand the situation they face and adapt their toolkits to fit the situation. APF allows for that adaptation as the project situation changes. The APF project manager is in charge of the approach rather than the approach being in charge of the project manager, as is the case with TPM projects.

In order to place APF in the proper context, I like to envision the various project-management approaches as being mapped into a very simple project landscape. That is the topic of the next section.

The project-management environment is an ever-changing one. It is defined by no fewer than seven interdependent variables. They are:

1. The characteristics of the environment in which the project will be executed

2. The characteristics of the project itself

3. The business process life cycle

4. The project management life cycle

5. The profile of the project team

6. The profile of the client team

7. The hardware/software technology to support the whole endeavor

While this may seem overwhelming, it isn’t. I’ll explore the complexities of this multi-dimensional environment with you and show you how to obtain and sustain an effective project-management presence in this changing environment.

For years now, management gurus have preached that an effective organization is one where there is a balance among staff, process, and technology. Staff is smart. Of that there is no doubt. How many times have you heard an executive say, “Just put five of our smart people together in a room and they will solve any problem you can throw at them”? That may be true, but I don’t think anyone would bet the future of the enterprise on the continuing heroic efforts of an anointed few. Technology is racing ahead faster than any organization can absorb, so that can’t be the obstacle. Process is the only thing left, and it is to the business process that we turn our attention in this book. But it isn’t just your normal everyday business process that interests us. We are going to look at a process that is really a process to define a process, rather than a staid and fixed approach—or recipe as I like to call it. Following the recipe analogy a bit further, I want to teach you how to create the recipe rather than just blindly follow some predefined recipe.

Balance between Staff, Process, and Technology

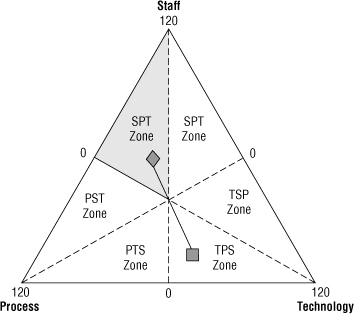

Several researchers have observed that successful organizations exhibit a balance among staff, process, and technology. As far as I know, no one has been able to build an assessment tool to measure the extent to which that balance exists. Several years ago, I undertook a project to develop an assessment instrument that measures the project-management balance in an organization with respect to the priority (and attention) it gives to staff, process, and technology. The assessment instrument is used to establish the current state and desired end state, and to suggest strategies for evolving from the current state to the desired end state. The underlying model that I developed is shown in Figure I.2.

Figure I.2 The Balance among Staff, Process, and Technology in an Organization

The triangle represents the three dimensions that determine project management balance: staff, process, technology. For the purposes of this assessment tool, Staff refers to the project team. Process refers to the project-management strategy that has been selected for the project. (The same model applies to any business process.) Finally, Technology refers to the tools, templates, hardware, and software that support the chosen project-management process.

The triangle is divided into six non-overlapping zones. Each zone is named with a combination of the letters S (representing Staff), P (Process), and T (Technology). Their ordering in the sector name gives us the ordering of their distances from each vertex, with the closest vertex listed first. The closer to a vertex a data point lies, the more important is that vertex to the organization. So, the combination SPT would mean that Staff is most important, Process less important, and Technology of even lesser importance to the organization. The ordering in this example also means that Staff (the project team) drives the choice of Process (the PMLC model) and that Staff and Process drive the choice of Technology (supporting hardware and software to be used).

The scores for each of the three parameters are linearly constrained. For this model the sum of their scores is 200, but it could be any number. This means that there is a dependency among the three parameters, and that every data point is constrained to lie within the boundary of the triangle.

The assessment data is summarized along these three dimensions and represented in the form of a straight line with a square at one end (current state) and a diamond at the other (desired state). The distance of the end points of the line to the vertices of the triangle give us a comparative measure of the priority of the given dimension to the organization. The closer the end point is to the vertex, the higher is the priority of the variable associated with that vertex. In this example, the location of the square tells us that the organization currently places a high degree of importance on Technology, less on Process, and least on Staff. In other words, the technology infrastructure has been dictated. That infrastructure determines the project-management process to be used, and the project team is chosen to be compatible with the established technology and process infrastructure. The location of the diamond tells us that the desired project-management culture is to have more-or-less equal importance placed on Process and Technology (Process has a bit higher priority than Technology), with the highest priority given to Staff. In other words, members of the project team are chosen first. They then determine the best project-management strategy to be used for the project they are to be assigned to, and finally they choose from among all available technologies those that best support their choice of project-management strategy. The SPT zone is the zone that should be preferred by most organizations, although not every organization will have the same desired end state. There will be variations depending on industry. For example, financial institutions will depend more heavily on Process and Technology, whereas the retailing industry might depend more heavily on Staff and Process.

The length of the line is directly proportional to the degree of organizational change that will be needed for the organization to reach its desired support environment. As part of my research, I expect to develop strategies to help the organization move from its current state to its desired state. If you are interested in more information about the SPT assessment tool, please contact me at [email protected].

In this book, I take the position that the characteristics of a project are the entry point into this model, and those characteristics drive our choice as to the team skills and competencies needed; then the team will determine the project-management tools, templates, and processes that should be used; and finally, the team and the tools, templates, and processes chosen will determine the best-fit technology to support it all. Obviously, this is not a recipe book to be blindly followed. Rather, it is a framework that teaches you how to create a recipe. Figure I.3 tells my story clearly. In other words, one of my objectives is to help you think like a great project manager and become a great project manager.

Figure I.3 Would You Rather Be a Chef Than a Cook?

Characteristics of the Project

When I think of the project-management landscape, I think of it at a higher level of abstraction than the seven variables discussed earlier. In keeping with my penchant for the simple and intuitive, I visualize it as a simple two-dimensional grid like the one shown in Figure I.4. The first dimension relates to the goal of the project. It has two values. The goal is either clearly specified (therefore completely known) or not clearly specified (therefore not completely known). The second dimension relates to the solution, or how you expect to reach the goal. That also has two values. The solution is either clearly specified (therefore completely known) or not clearly specified (therefore not completely known). If we intersect these two dimensions as shown in the figure, we have defined a four-category classification of projects. It is important to note that the boundary between clear and not-clear is a conceptual boundary. It is not quantitatively defined, but is only conceptually defined. This classification is simple, but it is inclusive of every project that ever was or ever will be. That is, every project must fall into one and only one of these four quadrants:

• TPM: Traditional Project Management (linear and incremental PMLC models)

• APM: Agile Project Management (iterative and adaptive PMLC models)

• xPM: Extreme Project Management (extreme PMLC models)

• MPx: Emertxe Project Management (extreme PMLC models)

Figure I.4 The Project-management Landscape

The projects in the TPM quadrant are those for which the goal and the solution are clearly defined. These will be simple projects that have been repeated a number of times in the past. There will be well-developed templates for all, or significant parts, of these projects. Because these projects are very familiar to the organization, the requirements will be known as well. Having complete requirements means that the solution will be clearly defined and the complete work breakdown structure (WBS) can be generated. TPM models will work quite well for these projects.

Next in order of increasing uncertainty are projects in the APM quadrant. The range of projects will be from those where the goal is clearly defined and most of the solution is known (perhaps with the exception of choosing how to render some features) to those where very little of the solution is known, and it must be discovered as part of the PMLC model chosen for managing the project. Because some of the solution is unknown, the risk associated with these projects is much higher than the risk associated with projects in the TPM quadrant. The successful completion of such projects will be critical to the organization. The business value must therefore be high enough to warrant taking on these higher-risk projects. Obviously, the requirements can’t be clearly and completely defined because that would imply knowing the complete solution. Therefore a complete WBS cannot be generated, and TPM Models cannot be used. What’s needed instead are PMLC models that incorporate solution-learning and -discovery features so that the complete solution can be found as part of executing the project. Our focus in this book will be on APF approaches which fall in the APM quadrant.

Next in the order of increasing uncertainty are projects in the xPM quadrant. For these projects, neither the goal nor the solution is clearly known; they must be concurrently learned and discovered as part of executing the project. These are usually R&D projects for which the risk of failure is very high. For these projects, the best-fit PMLC model must embrace a great deal of uncertainty and include investigative cycles that are designed to converge on a goal and a solution to support that goal. Even when that may be done successfully, there remains the question of business value. Does the solution to the now clearly defined goal offer sufficient business value to be useful to the organization? A good example of this situation is the project that eventually led 3M to the Post-it Note product. The glue produced from the original project did not deliver a product that had business value as originally defined, and sat on the shelf for about seven years until someone found an application with business value.

The discovery of that business value came from a project from the MPx quadrant. Projects in the MPx quadrant may seem like nonsense projects at first glance. Are there meaningful projects that consist of a solution looking for a problem? In fact there are. Wal-Mart’s initial investigation of the newly introduced RFID technology provides a good example. The question Wal-Mart was asked in this MPx project was: “Can you find an application (the project goal) of RFID technology (the solution) that has business value?” This sounds like an xPM quadrant project, but with the sequence reversed. That is why I call these projects Emertxe projects. If you haven’t already observed, Emertxe is Extreme spelled backwards. Both the xPM and MPx quadrants are heavily populated by R&D projects. The xPM-quadrant projects are projects looking for a solution to a fuzzily defined goal. The MPx-quadrant projects are projects looking for an application (the goal) of a technology (the solution or some variant of it) that has business value. xPM and MPx projects use the same PMLC model. An MPx project can be very simple or very complex. Refer to Chapter 8: APF in the Extreme for more details.

The best-fit quadrant can change as the project progresses. For example, early in a project’s life cycle, the goal may be clearly defined but the solution not clearly defined. That places the project in the APM quadrant, and the best-fit project management process for that quadrant can be chosen. As the project progresses, the solution may be discovered and become clearly defined. The project then moves to the TPM quadrant. The best-fit PMLC model approach may be changed from one in the APM quadrant to one in the TPM quadrant. There are a number of considerations when one is faced with this decision. They are discussed in Chapter 9: APF Frequently Asked Questions.

I contend that APM represents a class of projects that is continuously growing. I have traveled throughout the U.S., Europe, and Asia and have asked project managers what percentage of their projects falls into each of the quadrants. With very little variance in the estimates, they believe that 20 percent of their projects fall in the TPM quadrant, with 70 percent in the APM quadrant and 10 percent split between the xPM and MPx quadrants. I believe that the industry a company is in will have an impact on these percentages, but I don’t have any data to support that view. For example, in the building-construction industry, there should be a higher percentage of projects in the TPM quadrant than there would be for the financial-services industry.

My colleagues have confirmed these percentages from their own client experiences. There is a lot of consistent anecdotal evidence to support that distribution. I just haven’t come to a firm conclusion yet, since much of the APM quadrant is new. After we have gained more experience with APM projects and I hear more from my colleagues, we’ll have a better understanding of this landscape.

If we try to fit projects into the TPM quadrant when they really belong in the APM quadrant, then we are heading for trouble. This is what many have been doing even though they know that their approach is rigged. Many are not ready to embrace the alternatives. The results of a rigged approach range from mediocre success to outright failure. For years I have advocated that the approach to the project must ultimately be driven by the seven variables listed earlier. Once we have decided that the project is a TPM or APM or xPM project, then we can take these seven variables into account as we choose the specific best-fit PMLC model aligned with the chosen quadrant.

The APM quadrant is the focus of this book. The other quadrants will be referred to as needed to complete the discussion.

Even at this early stage in the discussion of the APM quadrant, you should be able to list some of the characteristics you would expect to see an APF PMLC model possess if it is to be successful. Here’s my list:

• APF requires a new mindset—one that thrives on change.

• APF is not a “one-size-fits-all” approach—it continuously adapts to change.

• APF utilizes a just-in-time planning approach.

• APF adapts tools, templates, and processes from TPM and xPM approaches.

• APF is based on the principle that you learn by discovery.

• APF guarantees “if you build it they will come.”

• APF seeks to get it right every time.

• APF is client-focused and client-driven.

• APF is grounded in an immutable set of core values.

• APF delivers maximum business value.

• APF eliminates all non-value-added work.

• APF approaches are less costly and require less time to execute than do TPM approaches.

• APF meaningfully and fully engages the client as primary decision maker.

• APF is based on a shared partnership between client and team.

• APF works—100 percent of the time! No exceptions!

Do I have your attention? Good! Read on and find out how APF approaches can significantly improve your company’s project performance and bottom-line impact.

Business Process Life Cycle

APF will have to integrate with other processes. They include software and systems development life cycles, product development life cycles, process improvement life cycles, and problem solving life cycles. There may be others as well. APF should be integrated into these business processes rather than having the business processes integrated into APF.

Project Management Life Cycle

As a project-management approach, APM must adapt to the project. It will not work effectively if it forces the project into its own set of rules and conventions. There will be several APM approaches that might be chosen for these projects. Among the current APM approaches, the industry includes the following software-development models:

• Adaptive Project Framework (APF) (the one discussed in this book)

• Adaptive Software Development (ASD)

• Feature Driven Development (FDD)

• Dynamic Systems Development Method (DSDM)

• Evolutionary Development Waterfall

• Prince2

• Scrum

• Rational Unified Process (RUP)

• Microsoft Solution Framework (MSF)

• Crystal

• xP

• and several others

Except for APF, a detailed discussion of these APM models is beyond the scope of this book. For more detail on TPM, APM, xPM, and MPx, see my book Effective Project Management: Traditional, Agile, Extreme, Fifth Edition.3

3 Robert D. Wysocki, Ph.D., Effective Project Management: Traditional, Agile, Extreme, Fifth Edition, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2009).

Profile of the Project Team

Alignment between the project-management approach and the team’s skills and competencies is essential for project success. For example, if the project is very complex and will require a lot of creativity and outside-the-box thinking on the part of the team, then choosing a team filled with professionals who like to follow a recipe won’t work. If this is your team’s profile and you have an APM or xPM project, this may require using an approach that isn’t the best fit for the project but does match the team strengths and preferences.

All APM approaches require a project team consisting of senior-level professionals who can work unsupervised. An APM project is no place for a rookie project manager or team member. Many APM project teams must be colocated. While there are some workarounds to avoid having a colocated team, they come with attendant risks. We’ll discuss the implications in Chapter 9: APF Frequently Asked Questions.

Profile of the Client Team

Just as the chosen approach must align with the team, it must also align with the client. For example, clients of the take-charge type that are quite comfortable with the lead position might resist an approach where they have little or no say in what happens. If they are capable of taking charge, choose an approach where they can take charge (Scrum, for example). You will always be there as backup if they tend to stray outside of scope.

Supporting Technology

I’ve always remembered what a friend and colleague used to say: Don’t kill mosquitoes with a sledge hammer. She was of course referring to the use of technology. I’ve run projects where the best-fit technology was a whiteboard with sticky notes and marking pens. Use the appropriate technology. Most APM projects can use a low-tech approach very successfully. Just because the computer is there, it doesn’t mean you have to use the latest and greatest toys. Your focus for an APM project should be on creating business value from what you deliver, not on how you deliver it.

Project Management Is Organized Common Sense

I keep things simple and intuitive. One way to simply and intuitively define project management is that it is a set of tools, templates, and processes designed to answer the following six questions:

1. What business situation is being addressed by this project?

5. How will you know you did it?

Let’s quickly look at the answers to these questions.

1. What Business Situation Is Being Addressed by This Project?

The situation is either a problem that needs a solution or an untapped business opportunity. If it is a problem, the solution may be clearly defined and the delivery of that solution should be rather straightforward. If the solution is not completely known, then the project-management approach must accommodate the learning and discovery of that solution. Obviously, these will be higher-risk projects than TPM projects, simply because the deliverables are not clearly defined and may not be discovered despite the best efforts being extended.

A project to take advantage of an untapped business opportunity can be done in several ways, discussed in Chapter 1: Overview of the Adaptive Project Framework.

Keep in mind that your project may be competing for resources with other projects that are addressing the same business situation but from a completely different perspective. For example, your project may be attacking one part of the problem while another project is considering a different part of the problem. It would be good if you knew this, because integrating the two projects into a single program may be cost beneficial. At least you would have more points of view to consider. The importance to senior managers of finding that solution or taking advantage of that untapped business opportunity will also compete with the importance of other project proposals.

2. What Do You Need to Do?

The obvious answer is to solve the problem or take advantage of the untapped business opportunity. That’s all well and good; but given the business circumstances under which the project will be undertaken, it may not be possible. Even in those rare cases where the solution is clearly known, you might not have the skilled resources to do the project; and if you do have them, they may not be available when you need them. When the solution is not known or only partially known, you might not be successful in finding that heretofore-unknown solution. In any case, you need to document what needs to be done.

3. What Will You Do?

The answer to this question will be framed in your project goal and objectives statements. Maybe you and others will propose partial solutions to the problem or ways to use the untapped business opportunity. In any case, your goal and objective statements will clearly state your intentions.

4. How Will You Do It?

This answer gives your approach to the project and your detailed plan for meeting the goal and objective statements discussed above.

5. How Will You Know You Did It?

Your solution to the problem or approach to the untapped business opportunity will deliver some business value to the organization. That is your success criterion. It will have been used as the basis for approving your doing the project. That success criterion may be expressed in the form of Increased Revenue or Avoided Costs or Improved Services. IRACIS is the acronym for these three areas of business value. Whatever form that success criterion takes, it will be expressed in quantitative terms so that there is no argument as to whether you achieved the expected business results or not. As part of the post-implementation audit, you will compare the actual business value realized to the estimated business value stated in the project plan that justified doing the project in the first place.

6. How Well Did You Do?

There are really four questions that comprise this question. The first and most important is, how well did your deliverables meet the stated success criteria? The second is, how well did the project team perform? The third is, how well did the project-management approach work for this project? The fourth is, what lessons were learned that can be applied to future projects? The answers are all part of the post-implementation audit.

Project Management Is Organized Common Sense

The answers to the above six questions reduce project management to nothing more than organized common sense. If it weren’t organized common sense, then why would you want to do it at all? So a good test of whether or not your project-management approach makes sense lies in your answers to these six questions.

Why I Wrote This Book

Project failure rates upwards of 65 percent (the most recently reported statistic4) are just unacceptable. This is not a new problem, but little seems to be happening to improve the likelihood of project success. Project managers continue to force-fit new project situations into old project-management approaches. What a waste of time and resources! A few years ago, I did some serious retrospective thinking about project failure, and asked myself what could be done. Quite by accident, I had two separate but concurrent client engagements that were good examples of the problem situation where the solutions were only partially defined. I knew a TPM approach would not work. I used those two engagements as the impetus for designing an approach to project management that accommodated the fast-paced, high-change business environment we were living in and would embrace convergence toward the solution using an iterative approach. The result became known as APF. APF is in the APM category of approaches.

4 Standish Group 2007.

How This Book Is Structured

The book consists of this introduction and ten chapters. The first chapter defines APF and puts it in context among project-management approaches. The next five chapters (Chapters 2 through 6) are each devoted to one of the five phases of the APF life cycle. Chapters 2 through 6 are all structured the same way. Each chapter begins with an overview of the phase. Its artifacts, processes, and deliverables are then discussed. The chapter ends with a section on one or more of the four case studies introduced below, as appropriate, a summary of the chapter, and several discussion questions for the academic market. Chapter 7 describes variations in the application of APF. Chapter 8 relates APF to Extreme Project Management approaches. Chapter 9 is a collection of frequently asked questions and answers. Chapter 10 takes a step back and positions APF in the context of the project-management landscape, with more of a future orientation.

Case Studies

As examples of the use of APF outside the software-development arena, I will be referring to the following four case studies. They are all examples of actual client engagements where APF was the approach. I have taken some editorial license to better illustrate APF’s characteristics. For the protection of my clients, I have disguised all of the names and the businesses. However, I have tried to preserve the nature of the engagement along with its failures and successes. Any resemblance to actual people or businesses is strictly coincidental.

Snacks Fifth Avenue: Kiosk Design

Snacks Fifth Avenue was looking for a way to create more interest for its shoppers and draw more traffic into its ten New York stores. The company viewed itself as somewhat of a boutique, and attracted high-end customers to its shops. It offered the most complete line of international snack foods and party products of any of its competitors. The kiosk had not yet been widely introduced in retailing, and here was an opportunity to do so profitably. My partner and I developed an approach to support the changing needs of the project and the discovery of the solution through iteration. That approach eventually became the initial version of APF that we successfully used for new-product development, and in this case resulted in a shopping kiosk that located food items, accepted orders, and assisted customers with maps and other directional aids. Interest in the shopping experience began to slowly increase as shoppers accepted and used the new technology. Store managers reported increases in activity as customers began to integrate use of the technology into their shopping experience.

Kamikazi Software Systems: Systems Development Project Management Process Design

Kamikazi Software Systems, a business-to-business and business-to-consumer Web site software development firm, built its reputation on fixed cost/time bids for custom designed internet/intranet sites. The development environment was obviously high risk. Recent trends showed that Kamikazi was not making its margins on smaller projects; in fact, the trend was definitely in the wrong direction. Through project reviews, Kamikazi learned that the number of change requests was growing and the process for managing those changes wasn’t holding up. The company approached us to help design, develop, and implement a project-management process that would work in its systems-development environment.

The development teams were seldom able to complete client projects within either budget or timeline parameters. Despite the fact that they had an established project-management process at CMM level 3, senior managers were unable to isolate the problem and correct it. What they did learn is that the internal clients were generally satisfied with the deliverables, but only after one or two unplanned revisions beyond the original specifications. Since these were not budgeted, these outcomes were not met by senior management with any joy or celebration. Because of this, APF’s just-in-time planning and iterative cycles were developed as a potential stopgap measure. The following results were achieved:

• Budget and timeline constraints were more consistently met.

• At first, the client’s representatives were uncomfortable with a variable scope, but because of their integral involvement in priority decisions and cycle planning, they were satisfied with the final deliverables.

• The general consensus was that projects finished in less time and with higher client acceptance than would have been the case if the old traditional approaches had been used.

• Having the client involved made problem solving and conflict resolution a much more productive exchange between the team and the client.

Pizza Delivered Quickly: Order Entry and Home Delivery Process Design

Pizza Delivered Quickly (PDQ) is a 40-year-old, family-owned, local chain of four eat-in and home-delivery pizza stores. PDQ’s stores are located in Woodville, a growing Midwestern city of 200,000. Recently, PDQ has lost 30 percent of its sales revenue, due mostly to a drop in home-delivery business. The company attributes this solely to its major competitor, a national pizza chain with ten stores, which started operation in Woodville 18 months earlier and is promoting a program that guarantees 45-minute delivery service from order entry to home delivery. PDQ advertises one-hour delivery. PDQ currently uses computers for in-store operations and the usual business functions, but otherwise is not heavily dependent upon software systems to help receive, process, and home-deliver customers’ orders. Pepe Ronee, PDQ’s Supervisor of Computer Services, has been charged with developing a software application to identify optimal “pizza factory” locations and with creating a software system to operate them more efficiently. In commissioning this project, Dee Livery, PDQ’s president, said to pull out all the stops. She further stated that the future of PDQ depends on the success of this project. She wants the team to configure the business to deliver pizza unbaked and “ready for the oven” in 30 minutes or less or deliver it pre-baked in 45 minutes or less. Given their current application of computer technology this was a daunting challenge but essential to the survival of PDQ.

Try & Buy Department Stores: Curriculum Design, Development, and Delivery

Try & Buy Department Stores is among the largest discount department stores in the world. Its Information Systems Department (ISD) comprises over 10,000 professionals, of whom approximately 2,000 were project managers. The systems development staff was organized along customer/product/service lines. There were 184 such groups. Each customer/product/services group operated independently, with its own processes, tools, and templates. There was a very strong sense of team and pride within each group. Despite cross-group project problems, of which there were several, the independent organizational structure did allow ISD to develop expertise in each customer group. Much of the success of Try & Buy was attributable to that unique structure. There were a number of problems, however. Projects were generally late, seldom completed, and poorly tested, and produced high-maintenance results. Adopting a project-management methodology that all 184 teams would be required to use was quickly dismissed as impractical and a waste of time and money. ISD senior managers felt that a training solution was what they needed.

Who Should Read This Book?

In general, this book will be of value to several different professional groups, but they all have a few things in common. You are creative thinkers. Rather than blindly following a task list, you ask, “Why?” If tasks don’t make sense, you either delete them or replace them with tasks that do make sense. You are fixed on delivering client-acceptable business value. You strive to do this in concert with your clients, not separate from them. This collaborative effort is the major strength of your approach. You are open to new ideas and concepts of effective project management. You are team players. You realize that only through a collaborative effort with your client will you have any chance of success. If you are struggling to deliver “knock-your-socks-off” service and know that you need some help, you have come to the right place. If this describes you, then you should continue reading. I have some great stuff to add to your toolkit! If this does not describe you, you need to do some serious reflection. The world is about to pass you by.

Project and Program Managers

These professionals are the primary beneficiaries of this book. As they encounter projects that just don’t meet the requirements of the traditional approaches, APF may be their best alternative. This book will give them a model that does.

Software Developers

APF is, after all, an agile software-development management process. There is much to learn about requirements gathering and what to do with the results. Meaningful client involvement and collaboration is a must. The change process is not the enemy. It can be a great asset if used correctly. All of these issues are discussed.

Product Developers

There is little mention in the literature about using APM models for product development. APF is designed primarily for that audience. Each of the case studies describes a non-software development application of APF.

Process Designers

One of the original applications of APF was a process-design project. The Kamikazi Software Development Company is the case study that traces the development of APF through the eyes of a systems-development process project. The case study provides an interesting look at a company that had been hell-bent on making its square peg fit a round hole, and it was costing dearly at the bottom line. It even took some time after the process was finished for the company to realize that it was the solution it had been looking for but was too blind to see. In retrospect, APF may have been the primary reason why this company survived the dot-com debacle and flourishes to this day.

Business Analysts

APF is a powerful tool for process-design and process-improvement projects. The investigative nature of the APF cycles is designed to uncover feasible process changes for measurable improvements.

Process Improvement Professionals

APF is a powerful tool for process-improvement projects. The same comments apply as above.

Research & Development Professionals

APF, xPM, and MPx share a lot in common. As the goal becomes fuzzy, the choice of approaches should migrate from APF to either xPM or MPx. The interesting commonality is that the structure of the phases of xPM and MPx is the same. Both xPM and MPx are also designed for discovery of both the goal and the solution to that evolving goal. Even at completion, the remaining question is, “Does the business value generated from the xPM or MPx goal/solution contribute acceptable business value?”

Problem Solvers

There are many problem-solving models; APF is one of them. In the typical APF project, you want to find a complete solution to a complex problem.

Putting It All Together

APF is a bold step forward in project-management approaches. To be successful requires that you reach inside yourself and summon up all the creative juices and outside-the-box thinking that you possibly can. APF requires the same from the client. APF is not for the faint of heart. It requires seeing the project as the unique entity that it is and drawing upon a vetted collection of tools, templates, and processes to craft the best-fit management approach for your project. There is no silver bullet, so don’t expect one. There is no recipe, so don’t look for one. But take solace in the fact that you are about to become a chef and not just a cook! If you apply what I have to offer, you will be prepared to effectively manage any project, no matter how complex and uncertain it might be. I’ve been there and done that many times, and I know that what I am advocating here works all the time!

In this book, I prepare you for an exciting, challenging, and rewarding career.