India has the world’s second biggest population and the largest number of people living and working overseas. Its economy and technology sector has seen enormous growth in recent times, in no small part due to it being the go-to location for outsourcing services. Combined with a colonial past, the people have a certain level of cross-cultural integration, including with those whose culture is vastly different to their own.

In many aspects, agility would seem to fit well with the culture. The people are team-orientated, relationship-driven problem solvers. Yet, in other areas there are barriers to overcome. Either way, the importance of the country on the world stage and of its people all around the world cannot be ignored.

History

Homo sapiens had arrived in the Indian subcontinent by at the latest, 55,000 years ago. This length of time means that people in this part of the world are second only to those in Africa in genetic diversity.1 Along with settlements in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia (an area in the Middle East roughly comprising modern-day Iraq, Kuwait, parts of Southeast Turkey and Eastern Syria), the Indus Valley region in the North of India and modern-day Pakistan was home to the first civilizations from around 3000 BCE. Records from Mesopotamia indicate that Kerala in the Southwest of India was a major trading center for spices between these early civilizations at this time.

As urbanization increased over several centuries, the traditions of “Śramaṇa” arose. Śramaṇa can be translated as “making an effort or exertion,” or, “one who performs acts of mortification or austerity, an ascetic, monk, devotee, religious mendicant,”2 and its traces are part of all major Indian religions and culture. Śramaṇa was to become central to the philosophies of Jainism and Buddhism, and of “Saṃsāra,” the concept of all existence as perpetual cycles, of the sun rising and setting, of birth, death, and rebirth.

The Maurya Empire, the largest empire ever to have existed on the Indian subcontinent, was to dominate South Asia from the 4th to the 3rd centuries BCE. A number of kingdoms and other empires that ruled over the area were to follow, including the Gupta Empire. Historians refer to this time as the “Golden Age” when developments in areas such as administrative practices, science, mathematics, literature, architecture, and religion (Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism) spread across Asia. India’s economy became the largest in the world, accounting for between one-quarter and one-third of the world’s wealth over the first 100 years CE.3

Continued raids on Indian kingdoms in the North and West laid the foundation for The Delhi Sultanate. Based in Delhi, it ruled large parts of the Indian subcontinent between the 13th and 16th centuries, and created the conditions for a mix of ideas and philosophies between Indian and Islamic cultures. The Delhi Sultanate took India onto the international stage, accelerating the mix of people, trade, technology, and thought, and it was one of the few powers able to repel the Mongol Empire.

In the 15th century, Sikhism emerged. Some of the core beliefs of Sikhism includes a belief in equality for all of humankind, justice and prosperity for all, and engaging in “Seva” or “selfless service.” Alongside this, prominent beliefs in Hinduism includes the concept of “Dharma” which includes behaviors, duties, rights, conduct, and virtue that makes an orderly universe possible, and “Karma,” the theory of moral cause and effect. All of these beliefs are in evidence today, as shown in the following story from Kiran Divakaran, who writes about the Sri Sathya Sai Super Speciality Hospital in Bangalore.

The Sri Sathya Sai Super Speciality Hospital, Bangalore: A Harmonious Work Culture With a Clear Mission

A company without a clear mission and without a culture where people freely interact, mingle, and allow people’s creative juices to flow freely cannot be in as good a position to create significant value compared to those that do. People should have freedom to express themselves without being threatened, judged, or ridiculed, and they should feel an innate sense of why their work is important.

I get to experience this firsthand as a volunteer, or “seva dal” as they are referred to, at the Sri Sathya Sai Super Speciality Hospital in Whitefield, Bangalore. I go there to do “seva” (service) whenever possible to do my bit for society. On each visit, volunteers are given a task on rotation. At times, it could be assisting the nursing staff, at others, it could be taking blood samples from one part of the hospital to another. It could be bookkeeping, or helping patients through different tests and taking test reports to other units for processing.

The hospital is unique, in that it provides free medical care. No billing counter can be found anywhere – quite strange for a hospital in a country where many commercial hospitals look at the patient as a device for making money. No charge does not mean low quality – the work done at the hospital is second to none. World-class care is carried out at the Sri Sathya Sai Hospital in the fields of neurology, cardiology, and ophthalmology.

I am used to going there amidst my work at IT companies in Bangalore. Working at the hospital is not in the least bit stressful. People work in shifts of reasonable hours. I see people who start work at 7.30 a.m. and finish by 3.30–4.00 p.m. although during peak times key personnel sometimes work beyond the call of duty when there are instances of an influx of patients. People give their soul for the betterment of their fellow man in an environment of trust. I have heard stories from doctors who told me that they were more efficient and performed at their best in this environment than in other purely commercial run hospitals where making money was the sole intent. The environment has brought out the best in people.

I have always wondered why companies big and small cannot have cultures such as the Sri Sathya Sai Hospital. My service at the hospital has left me thinking that this is how all work should be, instead of people being made to chase endless deadlines, having every last grain of effort squeezed out of them, and people left feeling discontented and empty.

Current Problems in Organizations

Many companies are dealing with unrealistic expectations from investors, and upper management that demand success too quickly. Workers that try to outsmart each other to win the biggest bonus. Wrong behaviors are rewarded and few companies measure true success holistically. Work environments are a far cry from being psychologically safe, and people have no sense of purpose beyond earning money. The Sri Sathya Sai Hospital is a real life example of an institution that has broken the pattern and acts as an example for all of us to embrace.

Agile Principles As a Basis

One of the principles of the Agile Manifesto states, “Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.” Creating motivated individuals needs an environment of psychological safety and having the right vision and mission. According to Kahn,4 “Psychological safety is being able to show and employ one’s self without fear of negative consequences of self-image, status or career.” Once you create the right environment with psychological safety, where everyone feels motivated to contribute their best to a clear mission, the results can be amazing.

A Clear Mission

At the entrance of the Sri Sathya Sai Hospital the following mission is enshrined: “Paropakartham idam shariram.” In Sanskrit this means, “the body is for the service of others.” High quality, cost-free medical care is provided to all people that come, regardless of caste, creed, religion, nationality, or financial status. Combining spiritual values and medicine, the hospital respects the patient as a human being. It views illness and diseases as a consequence of how people live in society and therefore, it is the duty of society to treat every person.5

When Isaac Tigrett, the founder of the Hard Rock Café, approached the World Health Organization (WHO) with the idea of a hospital that gave treatment for free, he was met with ridicule. Tigrett did not give up and was to contribute enormously to the initial setup of the Sri Sathya Sai Hospital following the sale of the Hard Rock Café. The hospital is sustained by interest on its initial investments and the generous ongoing donations from society at large, not only in financial terms and equipment, but by the large number of volunteers, doctors, and medical staff who contribute their time at the hospital in response to an altruistic higher calling.

A lot of naysayers predicted the downfall of the hospital, but it has proven to be sustainable. It continues to serve and go from strength to strength. Rigid cost control, continuous innovation, and course corrections help to control the costs. Cured and recovered patients are asked to help in ways such as donating blood or returning to volunteer when possible, although this is not mandated. The hospital’s mission ripples through to the patients, many of whom start to help to care for others, validating the model further.

A Harmonious Environment

Tigrett was introduced to Sir Keith Critchlow, Professor Emeritus of the Prince of Wales School of Architecture in London. Critchlow designed the Sri Sathya Sai Hospital in a way that makes it feel more like a piece of art than a hospital. Despite the ever increasing demand, the atmosphere is one of calm, assisting in the healing process of the patients. The staff are trusted and have the necessary tools to carry out their duties. The environment enables the people that work at the hospital to give their best. Whether patients, medical professionals, or volunteers, all feel cared for.

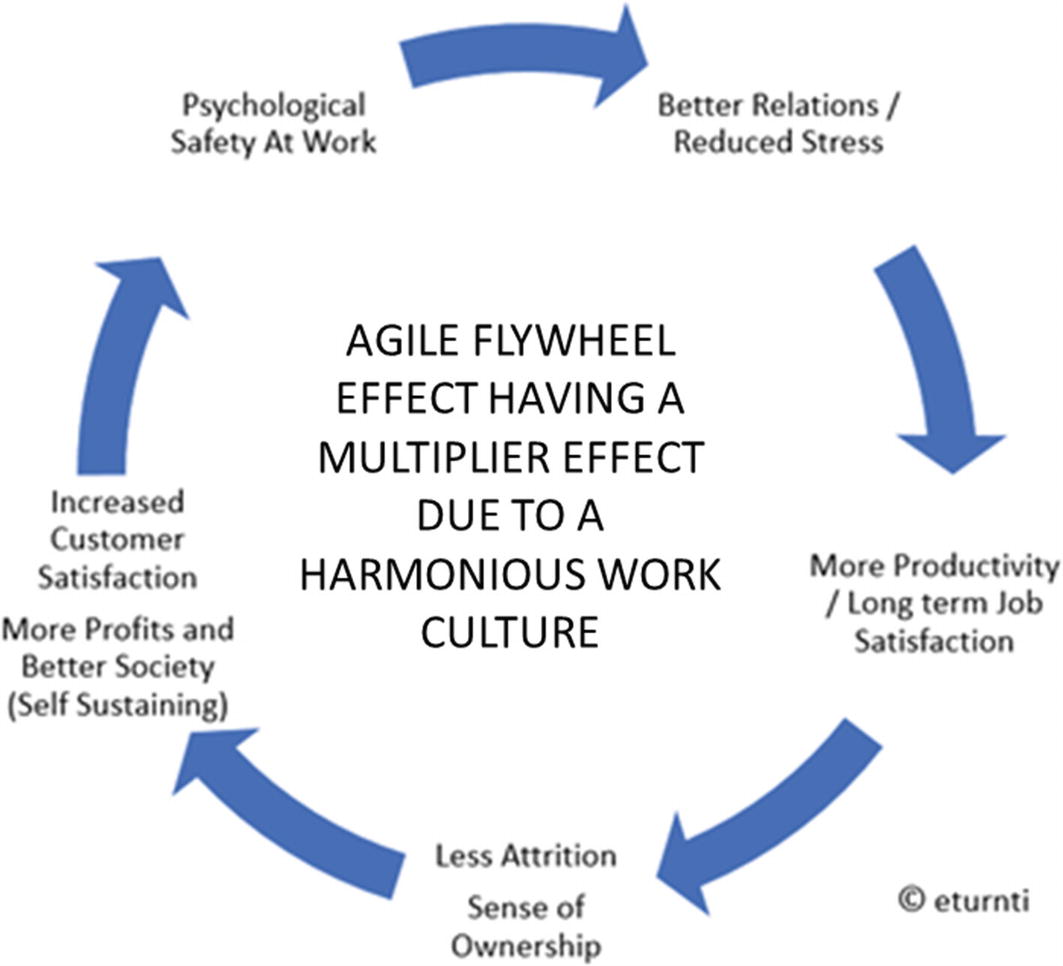

Agile Flywheel Effect

Agile flywheel effect

Environments where people are challenged without feeling threatened enable trust to be built and lead to organizations that can thrive.6 These environments of psychological safety, where there is a harmonious culture, and where there is a clear mission is now increasingly a characteristic of successful digital companies.

—Kiran Divakaran, principal consultant at Eturnti Consulting Pvt Ltd

Promote team psychological safety. Amy Edmondson, the Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at the Harvard Business School,7 talks8 about three simple things that individuals can do to promote team psychological safety.

Frame the work problem as a learning problem, not an execution problem.

Acknowledge your own fallibility.

Model curiosity and ask lots of questions.

Much of the approach and thinking that comes from the likes of Agile, Lean, Lean-UX, Lean Startup, and Design Thinking aligns perfectly well with the three elements that Edmondson describes. Work is seen as problems to solve. We accept “failures” (to learn fast). Proposed solutions are seen as assumptions to be tested. And the focus is on learning.

Continuing the history, at the end of the 15th century a Portuguese fleet discovered a route between Europe and India, paving the way for direct trade. The Portuguese set up a number of trading posts in coastal areas, and they were soon followed by the Dutch. War between the Dutch East India Company and the Indian kingdom of Travancore resulted in defeat on the Dutch side, and they never again posed a threat as colonizers. The French and the English also established their own trading posts, with the latter founding the East India Company (EIC) in 1600 to trade in the region.

The Mughal Empire conquered most of the Indian subcontinent in the 16th century and became the world’s biggest economy, larger than that of the whole of Europe. The Mughals intensified agricultural production, moved the economy toward industrial manufacturing, and developed a unique style of architecture which included the design and construction of the Taj Mahal. The Mughal Empire broke up in the early 18th century, paving the way for the European traders to exert political influence over the split Indian kingdoms. The EIC gradually expanded its power and influence, annexing Indian states and agreeing treaties with others where local rulers deferred power to the EIC in return for a certain level of autonomy and protection. Following the abolition of slavery in the 19th century, millions of Indian people were transported under contract to various European colonies as a substitute for slave labor. Thus began the growth in the large number of overseas Indian people throughout the world.

Grievances over land annexations, taxation, and cultural insensitivities saw growing unrest with the rule of the EIC during the 1800s. A large-scale rebellion by Indian soldiers employed by the EIC ran from 1857 to 1858 but was ultimately suppressed. As a consequence of the struggle, the British Crown took over all power from the EIC in what became known as the British Raj (Raj translates as “rule” in Sanskrit and Hindustani). Education was made a priority and would be based on the English language. Investment was made in infrastructure, including railways, canals, roads, ports, and telegraphy. However, India was made economically worse off overall because of the British. A series of diseases and famines killed tens of millions, but despite this, the population continued to grow.

To great outrage, Bengal was split into a Hindu Western half and a Muslim Eastern half in 1905. Though the British reunified Bengal in 1911, the action and the ongoing perception in clashes between Indian and British interests sowed the seeds for the independence movement. Under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, and inspired by the nationalistic leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who declared “Swaraj (self-rule) is my birthright, and I shall have it,” the Indian National Congress (INC) emerged as the leading political party calling for independence. Their approach to use non-violent methods included non-cooperation and civil disobedience.

Around one million Indian troops served in World War I. Recognizing the part that Indian people played, the Government of India Act 1919 was created, in principle creating a system of dual-rule. A peaceful protest that resulted in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, when troops were ordered to fire on protestors, led to Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement. Meanwhile, Muslim communities were divided on calling for an independent and united India, or a completely independent new Muslim state as called for by the All-India Muslim League. Muslims had always been a minority and some were wary of the prospect of being governed by a Hindu state.

After World War II in which millions more Indian people served despite non-cooperation tactics of the INC, the new British Labour government declared it was to end British rule of India. In August 1947, the states of India and Pakistan were created. One of the effects was the large-scale migration of the Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims moving between the two. In 1971, East Bengal, which had been part of Pakistan, became the independent state of Bangladesh following an independence war. The East Bengalis had support from India, and won their independence after growing international pressure on Pakistan.

India continues to have territorial disputes with Pakistan, most notably over the region of Kashmir, which resulted in three other wars between the countries before the end of the millennium. India has also had disputes with China, with the two going to war in 1962. After the United States and the United Kingdom refused to sell weapons to India, it turned to the Soviet Union with the two forming a strong economic and military relationship. India’s support for decolonization in Africa and other parts of Asia has helped it to develop good relations in these areas, as well as with Latin America.9 After the Cold War, India also developed relationships with the United States and the European Union.

Reforms and a liberalization of the economy that opened up foreign trade and investment in the 1990s has seen India become one of the world’s fastest growing economies in the world. Hundreds of millions of people have been taken out of poverty as India’s middle classes have grown. In addition, since independence, India has sustained the world’s largest multi-party parliamentary democracy when measured by population.

Insights

In addition to its international presence, India has inherited many influences from the British. These include a democratically elected parliament, use of the English language in education, business, and administration, the love of tea, and a passion for the game of cricket. While Hindi is the most widely spoken language, India has no national language. Instead, Hindi and English are listed as “official languages” in the constitution.10 In addition, the Indian caste system had many similarities with the British class system, and the British attempted to map Indian castes with British social classes. By introducing policies that gave preferential treatment to some castes over others and by using caste organization a central part of its administration, the British greatly influenced the system, resulting in lasting perceptions of superiority of one caste over another.

Since the 2010s, India has more people working overseas than any other country, with a diaspora population of around 17.5 million people recorded in 2019 according to the latest available data at the time of writing.11 India itself has become an IT services and outsourcing hub. It is no coincidence that most of the people we have spoken to have at some stage worked with off-shore teams based in India, or worked directly with people from the country. A certain level of international and cross-cultural awareness has therefore been attained above that of other cultures, including that of their former rulers.

The country has experienced rapid growth in its technology sector to begin to rival the United States and Europe. Bangalore is considered as a tech city and the “Silicon Valley” of India.12 According to NASSCOM’s report on the technology sector in India, the sector grew by 18 times in the first decade of the new millennium, with its Information Technology and Business Process Management industry worth US$191 billion and 4.4 million employees in 2020.13

A running theme in our conversations with people based in India or having been based there is the huge competition that there is between suppliers. This extends to individuals that feel they need to prove themselves to stand out from the crowd. Culturally, status is important, so the pursuit of certifications and qualifications to prove one’s self is common. Organizations do what they can to be competitive, catering for overseas clients and partners who themselves are looking to outsource in order to reduce their own costs.

Closed questions such as “will you complete it this month?” or, “can you deliver it?” are commonly likely to be answered in the affirmative. This often results in misunderstandings and frustration in outsiders who feel that commitments have been broken or that interlocutors have been untruthful when it is perceived that promises have been broken. Losing any business is loathed, but this is only a small part of the picture. While we heard evidence that promises are made that cannot be delivered in order to beat the competition, this behavior is also part of a culture where pride, politeness, saving face, diplomacy, and harmony – especially when dealing with people perceived to be more senior – comes first. We were told that the customer is “seen as god” and “you do not say no to a god” so any request that comes from the customer is accepted, even if it is unrealistic. Besides which, what has happened and what will happen are things that are not considered to be simply black and white. Giving a binary answer ahead of time on what is possible is unnatural in a culture unconcerned with agendas, and instead views what will happen as something that will emerge in time.

Another common mismatch with other cultures is in the differing perception of time. While wanting to be accommodating to foreign partners, there are bound to be misunderstandings between a culture where the concept of saṃsāra is embedded, and others that believe that the future can be controlled. A belief that time is made up of perpetual repeating cycles that includes birth, death, and reincarnation is at odds with one that focuses on making detailed plans complete with milestones and deadlines, especially when such deadlines appear arbitrary.

Despite the country’s geographical size, people in the cities are used to crowded conditions and little privacy. Perhaps because of this, people are warm and sociable, and friends are made easily. The communication style is such that listening with great respect is appreciated while dialogue can be verbose with long monologues. Yet the content can often seem ambiguous and perplexing for those unfamiliar with the communication style. Emotions are usually out in the open. We heard stories where emotional attachments can cause problems in Agile teams; openness means that too much information may sometimes be shared. Critique in retrospectives for example can be taken personally and felt as hurtful. Therefore, criticism is rarely given for the sake of harmony. Instead the focus is on praise, respect, and making friends.

Though Indian culture has inherited a sense of a class system from the British, Indian teams have a strong sense of collectivism. People come to each other’s aid when needed. We heard many stories of outside people working with Indian teams that were frustrated by the apparent silence of team members. People are used to command and control and defer to the leader. If someone is made a leader formally, they will act how they believe the leader should behave. Scrum Masters may act in a command and control way as it could be seen as a leadership position. If no leader is formally nominated, one will arise naturally from the collective group, and that person is expected to be the one to represent the team to outsiders.

Workplace trust is based on relationships ahead of tasks completed or achievements made, with nepotism a widespread factor. While great strides have been made, society remains patriarchal in varying degrees in different parts of the country. While India has seen spectacular economic growth in recent decades, poverty is also an ongoing and widespread issue.

Getting On and Around

Ziryan Salayi, an Agile Coach, Consultant and Facilitator from the Middle East but based in the Netherlands, shares some experience of bridging cultural differences with colleagues in India.

Understanding Culture Works Both Ways

As a consultant and an agilist, I have worked with people from all across the world. I have a Middle Eastern background, and my wife has a Vietnamese heritage. I also live in the Netherlands. So I have had many experiences understanding cultures from different perspectives. From all the stories I have to tell, I illustrate the power of cultural diversity with a description of my visit to Pune, India, with my previous colleague and manager.

The power of hierarchical awareness

Individual recognition vs. team recognition

Work relationships before and after office hours

Food as an elixir of trust

The Power of Hierarchical Awareness

My old manager is an example of an Agile leader. Her primary purpose is to make sure that people had all the expertise and freedom to deliver great products. She never used her hierarchical position in discussions and showed the courage to speak up to c-level management if decisions they had made would harm the team’s ability to self-organize. To top it off, she did this with genuine passion, and from a deeply rooted belief that this is the way to “manage” within an organization.

One day, she and I discussed the next steps in our Agile transformation. We noticed that there were some issues between team members in India and team members in the Netherlands. Lack of trust was one of these issues. Although we had weekly video conferences to improve, we believed that addressing the issue of trust and collaborating to improve was more effective when we saw each other face to face. We therefore decided to schedule a week’s trip to see our teams and team members in India and get to know them better. Management and team members in India were excited and happy to accommodate our stay. In preparation for our trip, the local managers in India planned a number of activities for our visit. My manager was surprised to see the first item on the itinerary was to “walk around the office and thank everyone.”

Manager: Ziryan, they are not talking about me? Right?

Me: I am afraid they are talking about you.

Manager: But, I am not going to speak in front of them. What do I have to say which is of any relevance to them? I’d rather the time be spent giving the teams a podium to speak up instead of me talking in my business-suit.

As right as she was if this was the Netherlands, she was not aware of a difference in culture. A cultural collaboration starts with showing respect to the needs of both cultures. In India, a talk from someone in a position of authority is important to acknowledge the value of the team members’ effort. Managers make the time to inspect the office and even take the time to thank everybody personally.

After a discussion, we ended up with us both wearing our business-suits on the first day. But, instead of my manager, it was me giving a speech and thanking everybody in the office for hosting us. Although I wasn’t a manager, they still treated me as higher up in the hierarchy. In order to respect the cultural expectations, the best alternative to my manager giving a speech was for me to give a talk. For the rest of the week, we could continue to work on gaining trust and have meaningful and open discussions despite the perception of a hierarchy.

Individual Recognition vs. Team Recognition

Being in an Agile organization, we value team effort and collaboration over individual targets and achievements. Yes, personal recognition is important, but team achievements are more important. We had this mindset, but we were in India where people have a different view.

On day three, we had a special event for the department. Everybody wore their best clothes and waited with full anticipation until it was 4.00 p.m. It was the annual event to look back at the results and communicate the plans for the rest of the year. Five minutes before the event, the manager in India approached us and told my manager that she had to make a special appearance. She had the honor of handing out the awards for individual achievements.

Manager: Ziryan, why are they asking me?

Me: Because you, as a manager from the Netherlands, are treated as a special guest.

Manager: But I don’t know them that well and I have no idea what they have done.

Me: You will receive details, and the management here will say some nice words.

Manager: But we are working Agile now. No one individual can achieve things alone.

Me: You are right. What are you saying?

Manager: I think we should honor all of the team members.

Me: I think we should, but that would have less impact.

Again, my manager was absolutely right. An individual achievement award made sense back when we were handing out tasks and worked more individually. In this transformation, we were focusing more on team results. From the perspective of team efforts, an individual cannot have achieved the results alone. And yet, having personal achievements is essential to motivate teams and team members in the Indian culture. Achievements like the employee of the month, best tester of the year, etc. are achievements one can take home so people’s family can be proud. “Out of all the thousands of employees, my son or daughter has received this award”!

Given that in some cultures, recognizing individual achievements is a way of motivating people from childhood, we cannot neglect this and focus only on team achievements. Parents in the Middle East often want their children to have respected professions like doctors or lawyers when they grow up, so it is important for individual’s efforts and progress to be rewarded. I remember how we had an annual “best student of the year” award in primary school in Iran and Iraq when I was younger. Before we came to the Netherlands, my brother and I were number one and number two in our class from the first grade to the third grade. Being awarded was a big achievement for me and acknowledgment of my effort, which made our parents proud.

Work Relationships Before and After Office Hours

My manager and another colleague arrived in Pune on a Saturday, and I arrived on a Monday. From day one, several colleagues from the Pune Office welcomed my manager and my colleague and gave them a city tour. They also took them to places to go shopping, go for food, etc. To my manager’s surprise, throughout the week, the colleagues from the Pune office kept joining us, bringing us to restaurants and fun places in Pune. After three days, my manager started feeling uncomfortable and guilty at the same time.

Manager: Ziryan, what shall we have for dinner tonight?

Me: Our colleagues were talking about bringing us to a biryani place tonight.

Manager: Wow, are they joining us again? Don’t they have a family to go to? I feel so guilty that they join us every day.

Me: It is their way to show their appreciation. They have arranged it with their families as well.

Often, in some cultures, working hours are for colleagues and outside office hours are for family. Occasionally you take people out for dinner or to a company event. However, usually, these are planned in advance. In Middle Eastern and Asian cultures, you see a different pattern. If you have visitors, you make sure they feel at ease and don’t get bored during their stay. When the colleagues from India visited us in the Netherlands, I had to explain to them that there would be evenings that they were on their own. Not because our colleagues didn’t value them, but because of the work culture in the Netherlands.

Food As an Elixir of Trust

Office hours in India start around 9.00 a.m. and end around 6.00 p.m. During these working hours, there are two very important moments – lunch and mid-afternoon chai. When we were working from a distance, colleagues in the Netherlands were agitated by colleagues’ work-ethics in India. Colleagues in India were often not available after the Daily Scrum. Also, they would not be available for 45 minutes just after our lunchtime. This behavior was high on my manager’s agenda to discuss with the managers in India. In preparation for our stay, my manager and I had a little discussion.

Manager: Ziryan, I hear many complaints about the work-ethics and availability of our colleagues in India. This is a high priority to discuss.

Me: OK, that is not good. What ethics are we discussing?

Manager: Team members are gone for hours, and I don’t think they are working the 8 hours they claim to do per day.

Me: Hmm… that sounds disturbing. What times are they absent?

Manager: Often after the Daily Scrum in the morning and after lunchtime.

Me: Ah, I see. I think they have very good reasons for this. They need this time!

Manager: What do you mean?

Me: Wait and see when we are there.

On the first day, we were invited to lunch with the local management team. They had taken 1.5 hours for this lunch. My manager was surprised. What are we going to eat that takes longer than the regular 45–60 minutes? However, she understood that it would maybe take more time because we were having lunch with the management team. On the second day, we had a 1.5-hour lunch and a long break in the afternoon for chai – this time with only two managers and some team members. The third day it was the same.

Manager: Ziryan, I still do not see why we have to have these long lunches and breaks in the afternoon.

Me: Why not?

Manager: It is affecting our effectiveness and productivity.

Me: OK, how much have you heard about our colleagues during these lunches?

Manager: I have heard a lot about their passion, their family, and their background.

Me: Would you have heard this if we did not have lunch?

Manager: I guess not.

Me: Exactly.

Although it sounds very unproductive, these moments are there to create a bond between team members. Team members share food and share moments. In Eastern cultures, food is the elixir of trust. When you have nothing in common, the love for food brings people together. If you investigate the time people are spending on breaks, lunch, and chai, it is probably less than people in the Netherlands office spend on chit-chat, coffee breaks (every hour), smoke breaks, lunches, and more coffee breaks in between meetings. The only difference is that in India, formal breaks take longer and contribute to the team building relationships and trust with each other.

Takeaways About the Difference in Cultures

Our issues between teams in the Netherlands and teams in India are not unique. For us to work together effectively, we need to change our perspective about the way we perceive different cultures. I often encounter that we want to get to know the other culture to find ways to get things done in the way we are used to in our own culture.

The trip in this story, among others, raised awareness for us to approach cultural diversity differently than we were used to. Understanding how another culture works is not sufficient to collaborate on an equal level. It takes openness and respect. For me, effectively collaborating in different cultures means I have to respect and be open to others’ habits and comply as much as possible with the other culture. Only then can I be seen as an equal and gain trust.

—Ziryan Salayi, Agile Coach, Consultant, and Facilitator at Scrum Facilitators

Several factors including past colonial rule and an embedded class system has instilled hierarchical systems and perhaps a cautiousness in the psyche. Hierarchical systems are common in organizations, and this helps to provide a sense of structure. In our discussions with practitioners, there was evidence that leaders who are open, eloquent, humble, provide safety, and take a carrot before the stick approach are loved. This style of leadership is likely to build trust and loyalty.

Establishing a trusting and psychologically safe environment where people are empowered may take time for those unused to such environments. Pranshu Mahajan, a Scrum Master with many years of experience working in various capacities in India, shares his story on the importance of learning to navigate Indian company hierarchies and building trust in Agile teams.

Trust: The Basic Building Block of Agile Teams

Scene 1

A group of young developers are sitting in a training room in Bangalore. They are eagerly awaiting the Agile Coach from another office of the company who is coming to help them start their team’s Agile transformation.

The team’s Scrum Master (who is new to the role and still learning how to be awesome) is sitting with them, finally able to see the process that she believed in and pushed for getting started. A point to note here: The team’s managers were not a part of these workshops.

The Agile Coach arrives and introduces the Agile Manifesto and what Scrum is, and then goes on to talk about how the team currently functions to explore ways to improve together.

The participants are a little shy when it comes to talking about their current problems. The Scrum Master keeps that concern on-hold considering this is their first session.

It is a 2-day training. On the second day, they continue from where they had left off. They speak at length about how they as a team can drive changes and make things better.

They discuss initiatives they could try and changes they could make starting tomorrow, etc.

The session ends on a high, and from the Scrum Master’s perspective, the training was great. Nobody raises anything major when feedback is asked for at the end of the sessions. It feels like people are happy with it.

So the day after, the Scrum Master decides to ask the team again what they thought of the training. He did this by organizing a variation of Rocket Retrospective to keep things quick, time-boxed, and get some feedback. Put simply, each member of the team writes anonymously on a post-it note their thoughts and all notes are placed face down on a table. The notes are then shuffled and revealed.

“It was great in theory but the Agile Coach doesn’t understand our problems.”

“How can someone from outside tell us how to fix stuff?”

“Until he works with us and sees our reality, he will propose a theoretical solution not applicable to us.”

“Let’s see what our site lead has to say about these changes that are being proposed from outside.”

“How can we agree on something when our manager is not here?”

Someone the team doesn’t trust came in and told them how to improve.

Indian companies are used to hierarchies. With management missing, telling the team to drive improvement on their own did not sit well with them.

It seems like the transformation stopped before it began. A rocky start.

This is a real story without making reference to anyone involved. I was part of this team of developers back then and went through my first “Agile Transformation” experience. I would like to point out that after this, it took a considerably long time for this team to get started with an Agile adoption again.

Scene 2

The same company, another department, another team. This team has heard a lot of things about how some of the other teams in the company have been transformed. And they are looking to start their own journey.

The new Scrum Master for the team discusses how they can kick things off. They talk about how they can learn this “Agile mindset” and about the potential improvements that they could make, etc.

Even though the Scrum Master is new to the team and the company, she has already accomplished her first step in a short period of time: to build trust with the team by showing that she is part of the team and will be going on the journey with them.

The next few weeks sees her organizing workshops to educate the team about Agile methodologies, the Agile mindset itself, ways of working such as Kanban, Scrum, etc. She and the team have intense discussions about how they can improve the current ways of working. And how to take the first step.

These workshops are messy and what comes out is not the answer to the team’s problems. But the first step toward a goal they envision together.

Next up, the Scrum Master takes these outcomes and gets the managers on board. She gets the managers excited about the things they agreed with the team. This excitement trickles down to the team (which is always a good thing).

The team commits and starts working toward their goals. There are a lot of arguments, some restructuring of the team, some people moved to other teams, and others joined this team. But they manage to pull through and achieve a lot of the things they highlighted in the Agile workshops.

One day, the Scrum Master decides to talk to the people about how they think this transformation journey is going. She decides to facilitate a retrospective focusing on how the team feels about how things are going.

“I did not know it was going to be so hard. But since we could focus on the problems we wanted to solve, it became worthwhile.”

“This only happened because we did it together. We all work together and it’s easier to communicate.”

“I was telling our management to stop sending consultants from outside. We know the situation better than they could. See, this worked out beautifully.”

“It’s great that we have someone who knew our situation before they decided to start solving problems for us.”

The team discussed and figured out the next steps together. There was no one from outside of the team telling them what to do. The Scrum Master was already part of the team.

The management being on board and supporting the team meant everyone was all in and committed. We do not skip hierarchies in India.

This team had a great start to living the Scrum values. I was part of this team. I was transitioning from being a development team member to a Scrum Master and this was a great learning experience. Later when I started supporting a different team as a Scrum Master, I relied on this experience a lot and it helped me grow into the role.

This team hasn’t stopped improving to this day. The last time I spoke to them, they were trying to make things better for themselves every week and trying to make things easier for the people who use their products. And they were living the values of commitment, courage, focus, openness, and respect.

The Lessons

The first, and most important step that you need to understand while trying to drive changes in India is building trust.

I cannot emphasize this step enough. For as long as I have worked in India (almost a decade) in a variety of roles, ranging from software development and support, to leading people, to functioning as a Scrum Master, this one factor has stood out to me the most.

Trust alone transcends the role that you have in a company. Be it a Scrum Master/Agile Coach, People Manager, Director, etc. Unless you have your team’s trust, things will not go smoothly.

This becomes especially true if you want to drive a transformation.

The second thing is to learn how to work within hierarchies.

This might sound a little weird considering the Agile methodologies talk about self-organizing and self-managing teams. In Scrum, for example, the emphasis is on three roles, each with their own accountabilities.

Again, start by building trust with managers. Keep them in the loop and make them understand the what and why of the Agile approach before you start with the team.

You might at this point say – moving away from command and control hierarchies is exactly what we are trying to achieve.

To which I say – yes, I agree. Also, a Scrum Master/Coach has to be tactful. Understanding the art of the possible is a skill Scrum Masters need to learn.

My third tip is to give feedback one-to-one in person.

Indian people generally don’t do well in giving or receiving feedback in an open setting. This is something to watch out for. For feedback of an individual (not team-related), make a note, have a one-to-one with them, and talk.

Then help the team and the individuals grow. Help them create an environment where exchanging feedback is appreciated and safe. It’s not easy, but the journey is a great one to take because what you get in the end is a psychologically safe, self-managing team who can be constantly improving to deliver great quality products to customers.

The final piece of the puzzle – build relationships outside of work.

We Indians value our relationships a lot. Be it personal or professional. Unless we get along on a personal level, we will not really get along professionally. We believe the people we trust would do no harm to us. One example in a professional context where trust would be broken is yelling at an individual in-front of the rest of the team. We need to build trust, and see others wherever they are in the hierarchy as a friend (and it is not super hard to make friends here). Once you penetrate the circle of trust, it is effortless to discuss, implement, and drive improvements.

—Pranshu Mahajan, Scrum Master (Helping teams in their journey from being good to great)

Hierarchical structures do not automatically prohibit agility. Though we have spoken about hierarchy in organizations as a barrier to adoption in a number of instances in this book, how they work in practice can take many forms. As we saw in many South American companies, the structure may appear hierarchical on paper, though the organizational culture allows things such as horizontal communication, and peers resolving issues rather than escalating to a manager. In Japan, we saw hierarchical structures, yet the focus is on consensus building, getting people involved, and managers as servant-leaders. Building trust and respect, as we saw in Pranshu’s example, helps everyone to get into the desired mindset for servant-leadership and self-organization to succeed.

Many may feel uncomfortable transitioning to a self-organizing state, and will search for a leader for guidance. As mentioned earlier, in the absence of a formal leader in a group, one will naturally emerge. There may be a temptation to push against this for an Agile team, to insist on equality, but it could be argued that this is an acceptable form of self-organization. The team itself has agreed that this is the way they want to operate. As an outsider, it is advised to first build a relationship with the individual that emerges as leader – everyone else will follow.

Historically in hierarchical organizations, team members are used to, and feel the need to be given, explicit instructions to carry out. However, as in every culture and organization, when an environment of trust and safety has been established, people can prove themselves to be accomplished and skillful problem solvers.

A desire to deliver a good service, combined with business partners eager to progress, as well as the communication style, means there can be a tendency for overcommitting. Planning will be more successful when using open questions such as “How long do you think we will need?” This gives team members more room to express reality than questions that corner them into having to give a yes or no answer, such as “Will it be ready by X date?”

People are warm, respectful, communicative, and quick to share what they have equitably. It is relatively easy to build good relationships. Life is centered around family, so enquiring about people’s family and showing respect for their achievements will win hearts. It is unlikely to take very long before enquiries are made about your own marital status, children, etc. Marriage is so central to life that it is a point of fascination in many conversations.

Making friends and building relationships for the long term are more important than any short-term deal. Oral agreements are just as valid, if not more so, than written documents. People are used to uncertainty and ambiguity being part of life; the future is seen as uncontrollable, and truth does not have a binary answer. Facts and appearances have many moving parts and are open to interpretation and negotiation, so some decisions should not be made quickly. Acceptance of these factors has led to a flexibility in dealing with and managing uncertainty that perhaps other cultures could do well to learn from.

Agile Community Events and Meetups

AgilityToday: http://agilitytoday.com/

Agile Software Community of India: https://agileindia.org/

Agile Network India: https://agilenetworkindia.com/

Discuss Agile Network Bangalore: www.meetup.com/discuss-agile-network-bangalore/

Agile Transformation Minds (ATM) – India: www.meetup.com/atminds/

Scrum Bangalore: www.meetup.com/ScrumBangalore/