We the People: Racial Realism in Politics and Government

One might wonder why government employment should get its own chapter. After all, most government employees are skilled workers and professionals, similar to the skilled and professional workers who were the focus of Chapter 2. It is also the case that since 1972, Title VII has applied to government employment.

Yet government employment is also very different. This is because government employers sometimes have goals that private employers do not. In some cases, government employers may perceive a need to pay back voters with government jobs. Another objective may be to provide role models for young people. For both of these reasons, racial signaling has far more importance in government employment than in private employment, where it matters only sometimes in white-collar employment and hardly matters at all in blue-collar jobs. Yet racial abilities also matter a lot in some government jobs, especially policing and teaching. Thus, the American tradition of racial realism in government jobs is rich and long—and it has become even richer and more elaborate in keeping with the increasing racial diversity of the population.

Yet government employment is also very different, and racial signaling especially important, because it relates to power and nationalism in unique ways. As described in Chapter 1, government jobs are deeply linked to a group’s sense of having a say in their destiny—a big factor in the perception of government legitimacy. Denial of representation and influence in government has been a factor in secessionist movements and ethnic nationalism around the world.1 In some contexts, visible inclusion in the government (what political scientists called “descriptive representation”) can lead to better representation of previously excluded interests, allowing a wide and diverse segment of the public to feel included, and thus increasing the stability of the government.2 Widespread racial unrest and violence are certainly not unknown in the U.S., and the racial violence of the 1960s, as well as the six straight days of fighting that took place in Los Angeles as recently as 1992, reminds us that it can happen here.

Another key difference with government employment, and a factor that makes it necessary to treat it separately, is that it involves a different legal regime. Both Title VII as well as the Constitution regulate government employment. The Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws creates, as we shall see, new possibilities. The framers of the Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment, apparently preoccupied with other concerns, wrote nothing about “BFOQ” employer defenses. There is, consequently, no explicit constitutional statement of an exceptional lack of a BFOQ for racial discrimination in government employment as there is in Title VII. This clears the way for a judge-made race BFOQ. The problem for racial realism is that few judges have seized this opportunity: for the most part, courts allow hiring for racial abilities or signaling only in the context of law enforcement.

Nevertheless, racial realism (or its advocacy) is common in the practice of government employment, whether or not it is sanctioned by the law. This chapter focuses on three contexts of government employment. I begin at the top: elected positions and appointments made by elected officials. Technically, these are not “jobs” in the way other positions in this book are jobs. Presidents, members of Congress, mayors and the like are obviously not “hired”; they are chosen by voters. Furthermore, the appointments they make are not subject to Title VII any more than their election is governed by Title VII.3 At the federal level, for example, appointments are governed by the Constitution, which says little about the process other than that the President is to make the appointments with the advice and consent of the Senate. This constitutional provision was geared not toward equal opportunity, but toward avoiding the appointment of cronies.4

Yet these officials do work for us. They have jobs, and they draw paychecks. More importantly, if we are going to assess which strategies of managing race in employment are dominant in America, it is essential to understand how race matters at the top. What messages are our political leaders sending when they make appointments, and what messages are we sending to them when we elect them?

I will argue that our political officials entrusted with enforcing the laws—that is, executive branch officials—commonly make appointments based on interests in racial signaling and that there is a long history of this practice, though it used to be done more narrowly. While the only race that mattered was whiteness for most of the nation’s history, racial signaling with nonwhite appointments has occurred at the local level for more than a century, and at the federal level, it began with the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration. In recent decades, it has expanded beyond black and white to include Asians and Latinos, and it can be seen in White House appointments, positions of party leadership, and appointments to the judiciary. I also review evidence that supports the notion that race has important effects in the highest levels of government.

Next, I show how racial realism has shaped advocacy and employment in two key areas where citizens regularly interact with government: policing and teaching. Here again there is a long history of racial realism in practice, and an even longer history of advocacy, particularly in teaching. The notion that police officers and teachers should be hired and placed with an eye toward their racial abilities and signaling continues to be alive and well, and has changed and expanded as American demography has become more racially diverse. There is evidence to support racial realism in both cases, though as usual, that evidence is mixed.

Finally, I will explore the ways that the courts have treated this issue, highlighting their use of constitutional jurisprudence to get around the problem of a lack of race BFOQ in Title VII, as well as their inconsistency in crafting these legal rules. Courts have been more open to finding a compelling interest to use race in the hiring and placement of police officers than in teaching—even in instances where minority officers have resisted assignments to mostly minority neighborhoods—as they have identified an “operational needs” compelling interest that justified racial realism. On the other hand, racial-realist ideas common in education, such as the notion of racial “role models” for students, have either found no support or have been explicitly prohibited.

I also explore the implications of one of the Supreme Court’s most important rulings on race and compelling interests. Though it dealt with racial preferences in university admissions, many hoped the case would act as a catalyst for changes in employment law and increase opportunities for at least government institutions to use race in their hiring. In 2003’s Grutter v. Bollinger, the Supreme Court articulated a governmental interest in racial diversity due to its civic benefits, which would seem to have relevance to both upper and the lower positions in government employment. However, despite initial speculation, the Grutter opinion had only a very limited influence on government employment practices.

In emphasizing non-Title VII “employment” at the outset—that is, the ways that elected officials use race in governing the country—I am very deliberately trying to highlight the inconsistency in our laws and the practices of government officials. There can be little doubt that the leaders of American government regularly practice racial realism, and this makes it all the more remarkable that civil rights law offers so little authorization for what these leaders so clearly believe is the right thing to do.

Racial Realism in Political Appointments: An American Tradition, Now Multiplied

When Americans choose political leaders, they tend to choose those who look like themselves. White Americans have typically supported white leaders, and other races supported leaders of their own race. The dominance of white elected leaders is thus largely the result of the numerical dominance of white voters. The election rates of black and Latino leaders increase when these groups become a majority or near majority in a district.5 Throughout American history, elected Asians in the Senate have for the most part represented Hawaii, the only state with an Asian plurality.6 It is not clear why voters tend to vote for their own race, but it would seem likely that many use racial-realist strategies when voting, for example when considering which candidates will have the ability to represent them effectively. Knowing this, elected officials tend toward racial realism when making appointments as well.

Early Racial Realism in Urban Politics

Racial signaling for nonwhites became entrenched in the politics of local appointments by the early 1900s, when nonwhite populations with voting rights became large enough to sway elections. The strategy was to use the racial signaling to show that voter support was appreciated and to suggest that particular races had a voice in the government. As explained by political scientist Harold Gosnell in his 1935 study of the growing importance of African-Americans in Chicago politics, “When the Negroes had developed a small professional and business class, when their importance to a given faction or party was strategic, when they found white politicians who were courageous enough to back them under the fire of hostile sections of the white public, they secured some local and state positions.”7 But a hundred years ago, racial signaling required a delicate balancing act. A mayor wanting to reward blacks for their support had to be careful to avoid angering racist whites, who generally would allow immigrant groups to get their patronage rewards or have their own candidates but resisted sharing power with blacks.

In 1915, Chicago’s mayor, “Big Bill” Thompson, who enjoyed great support from the city’s African-Americans, was thus forced to defend his appointment of blacks to some quality government jobs:

My reason for making such appointments were [sic] three fold: First, because the person appointed was qualified for the position. Second, because in the name of humanity it is my duty to do what I can to elevate rather than degrade any class of American citizens. Third, because I am under obligations to this people for their continued friendship and confidence while I have been in this community.8

In city politics, the issue was whether city hall could use racial realism in the same ways that it had used ethnic realism to benefit such white groups as the Irish or Italians. As Thompson’s defensiveness shows, it was not always an easy sell.

Origins of Racial Realism in the Federal Government: New Deals and Great Societies for African-Americans

Nonwhite voters found the federal government far less welcoming than cities like Chicago. They could find jobs, but opportunity was sharply limited well into the twentieth century. President William Howard Taft’s administration was the first to segregate the federal civil service, but Woodrow Wilson did the most to formally institutionalize that policy. It stayed segregated until the end of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration, though discrimination against African-Americans remained the rule until Lyndon Johnson took office.9

Despite his efforts to segregate, Taft was also a pioneer in that he was the first president to appoint an African-American to a position with policymaking power when he appointed William H. Lewis to be Assistant United States Attorney General.10 But it was FDR who, late in his first term, established racial realism as a normal management strategy at the federal level. In 1933, black leaders pressured Roosevelt to create a position for someone to oversee the treatment of blacks in his new programs. Clearly attempting a politically sensitive balancing act, the president chose a white Southerner for the position. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP told the administration that blacks “bitterly resent having a white man designated by the government to advise them of their welfare,” and the administration responded again, this time by adding Robert Weaver, a Harvard-educated economics Ph.D., to serve alongside the white official.11

Despite the inauspicious start, there was progress. By 1935, Roosevelt had appointed more than forty African-Americans to low-level positions in cabinet departments and New Deal agencies. Several of them would meet regularly with the president to advise on racial matters. They were informally dubbed the “Black Cabinet.”12

Roosevelt’s policies helped move African-American support from the Republicans to the Democrats. Truman’s support of civil rights helped to consolidate this support. Eisenhower, however, managed to win 40 percent of the black vote and rewarded that support with the high-level appointment of E. Frederic Morrow as a White House adviser.13 Still, the title of Morrow’s memoir, Black Man in the White House, trumpeted the exceptional nature of a high-level black appointment in the 1950s.14

Lyndon Johnson, who did so much for African-American causes, also appointed the first black cabinet secretary, Robert Weaver, as the head of the new Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The story behind Weaver’s rise from a low-level official in the Roosevelt administration to higher level posts under John F. Kennedy and Johnson, explored in rich detail by historian Wendell Pritchett, is useful to recount because it highlights the strategic thinking driving racial signaling in high-level appointments, as well as the meanings of both blackness and whiteness in an era when classically liberal nondiscrimination became the law of the land.

During the hard-fought 1960 campaign, Henry Cabot Lodge, the vice presidential running mate of Republican candidate Richard M. Nixon, announced to an audience in Harlem that Nixon would make history by being the first president to appoint an African-American to a cabinet position. Worried about his standing in the South, Nixon denied Lodge’s claim, and then Lodge denied he had ever made it. Kennedy said that making a appointment on the basis of race was “racism in reverse, and it’s worse.”15

Kennedy, however, won three quarters of the black vote, and—reflecting the hypocrisy that is so common in American racial politics—sought to reward blacks with federal appointments. Over the resistance of Southern members of Congress, Kennedy appointed Weaver, who had been a civil rights activist focused on segregation issues in New York City, to run the Housing and Home Finance Agency. One black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier, said approvingly that the appointment was a strike against housing discrimination, “because the new administrator, not appointed to the job necessarily because of his race, but because of his ability, will serve as a symbol.”16

Weaver’s rise would continue. Congress passed the Department of Housing and Urban Development Act in 1965, creating what came to be known as HUD. Johnson ultimately decided to appoint Weaver to the new cabinet post, but it took several months of analysis, as there were many concerns about his suitability for the job, some of which were related to race. For example, Senator Robert F. Kennedy (D-NY) argued that Weaver’s race was a problem in both the North and South, and both Kennedy and Johnson agreed there was “some advantage to having a white man in there.”17 Worrying about relations with Congress, Johnson told Roy Wilkins of the NAACP that “a white man can do a hell of a lot more for the Negro than the Negroes can do for themselves in these cities.”18 Yet Johnson was also very concerned about the racial signaling value of a Weaver appointment to black voters. He worried that appointing a white person would be a letdown to “little Negro boys in Podunk, Mississippi,” and that despite Johnson’s achievements for civil rights, blacks would see the Weaver snub and conclude that “when you get down to the nut-cutting … this Southerner just couldn’t quite cut the mustard—he just couldn’t name a Negro to the Cabinet.”19

While Johnson agonized about the decision, the black press urged him to move forward, with the Baltimore Afro-American arguing that Weaver would “wipe out big-city racial ghettoes,” the Chicago Defender maintaining that Weaver was the most qualified candidate, and the Pittsburgh Courier again playing up the racial signaling, stating that Weaver’s appointment “would mean that a Negro was a full-fledged member of the top power structure and would counteract much of the urban Negro revolt to the Republicans….”20 Roy Wilkins warned in a public statement that failing to appoint Weaver “might galvanize the Negro community into thinking that in rejecting Mr. Weaver [Johnson] was rejecting them.”21

Johnson told his attorney general, Nicholas Katzenbach, “I doubt this fellow will make the grade” and predicted he would be “a flop,” but at the same time, Johnson could not resist the powerful value of racial signaling. Therefore, “We’ve got to get a super man for number two place [sic], and then send this fellow all around policy touring and let this second fella do the work with the Congress and with the President and with all the other people.”22 Satisfied with this plan, Johnson announced on January 13, 1966, that Weaver would be the secretary of HUD. Civil rights leaders and the black press cheered.23 Johnson would also ingratiate himself further with civil rights groups when he nominated Thurgood Marshall to be the first African-American on the Supreme Court—a move the NAACP had lobbied for since the Kennedy administration.24

As the story of Weaver’s appointment makes clear, presidents may make appointment decisions while seriously considering the racial implications of their decisions. It also shows a widespread expectation of racial realism in appointments, and media elites and advocacy groups typically lobby specifically for appointments, emphasizing the importance of racial signaling or racial abilities or both.

Moreover, advocates for African-Americans were far from alone in this kind of lobbying. Latino groups were especially active during the Johnson and Nixon administrations, directing much of their lobbying energy toward securing government representation.25

By the late 1970s, presidents did not have to be pushed very hard. Jimmy Carter kept computerized records of the race and gender of his political appointments. During his term, 21 percent of his appointments were nonwhites (and 22 percent were women), including two black cabinet members (Donald F. McHenry was Secretary of the Army; and Patricia Roberts Harris was first Secretary of Housing and Urban Development and later headed Health, Education, and Welfare).26

The Republican Move to Anti-Affirmative Action—and Racial Realism

The current period of racial realism in government, in which both Republicans and Democrats know that how they manage racial signaling with their elected leaders and appointed officials is important to party success, began in the 1980s with the Reagan administration. This is also the period when the Republican party moved squarely to define itself as the party of racial conservatism (which by the 1980s meant classical liberalism), and thus to take stands opposed to affirmative action and other policies supported by African-American leaders. Though appointments of nonwhites fell to 9 percent, less than half of Carter’s percentage (women were 37 percent of all appointments), Republicans’ stated opposition to affirmative-action liberalism did not mean opposition to racial realism, as I show below.27

The main Republican strategy is to signal to white voters that they are not doing anything special for blacks—but also that they are not racists. Both parties increasingly appoint Latinos and Asians to top posts, and Republicans especially display their nonwhites as prominently as possible. As Paul Frymer has shown, the challenge for Democrats is to keep black voters loyal while not alienating white voters.28 Democrats have continued to support both affirmative-action liberalism in policy and racial realism in practice, but by the 1980s, some leaders in the Democratic party were arguing that being too closely identified with the interests of African-Americans was hurting the party’s chances at the ballot box.29

The primary way that Republicans have managed race has been to find, promote, and display people of color who criticize any or all racially liberal policies. We can see the importance of this racial signaling strategy for the modern Republican party in the meteoric rise of two African-Americans: renowned economist Glenn Loury and future Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

In the 1980s, Loury was building on his groundbreaking work on “social capital,” or how network ties play a key role in social mobility. He had begun to question the role of the government in ameliorating black inequality. If discrimination was not the key factor keeping blacks down, he reasoned, then government attempts to fight it, such as affirmative action, might be misguided.

Loury came to the attention of Republicans after his 1984 speech to a group of civil rights leaders in Washington, DC. To an audience that included Coretta Scott King and John Jacob, the president of the National Urban League, Loury put surprising emphasis on a pillar of conservative thought: that the black poor have a responsibility to help themselves, including in such areas as low educational achievement, high crime rates, and out-of-wedlock births. Many in his audience were appalled.30

But conservatives loved it. The New York Times noted in a profile, “As a black critic of racial liberalism, Loury rose rapidly in Republican public-policy circles.” He sat with Reagan at a White House dinner, and his friend Bill Bennett, then Secretary of Education, offered him a position in his department as undersecretary. Other conservatives embraced Loury, including many identified with the neoconservative movement.31 Loury would go on to chair the board of a new initiative, the Center for New Black Leadership, organized to constitute a new and different (that is, not liberal) black political voice.

But Loury became disillusioned with conservatism, particularly on matters of race. In his view, the strand of conservative thought with which he identified, neoconservatism, which acknowledged at least some shared responsibility to bring about more racial equality, was losing its distinctiveness.32 The emerging conservative positions on race in the 1990s, such as the resurgence of biological explanations of poverty rooted in theories of racial differences in intelligence,33 offended Loury both intellectually and morally. He turned away from conservatism, and conservatives then turned their backs on him.

Loury later authored a very personal and insightful reflection on his relationships with conservatives, focusing on Jewish neoconservatives. Writing in the pages of CommonQuest, a short-lived but bold magazine focused on African-American and Jewish relations, Loury wrote of the signaling value of his race:

That I existed—a black neoconservative with the courage to lend his voice to the chorus, even while being branded a traitor by other blacks—was a certain kind of statement…. [M]y “breaking ranks” helped to confirm [the neoconservative positions on race] as valid and non-racist. Interestingly, given the color-blind mantra which animated much neoconservative criticism of affirmative action policies, my color became part of my qualifications as an intellectual warrior. Had I been white, my “brilliant, perceptive, courageous” insights would surely have seemed a lot more like pedestrian, commonplace complaints…. How could I insist to my black detractors, who accused me of being disloyal, that they should simply respond to my arguments, when it was not only, or sometimes even mainly, the power of my arguments that mattered?34

The racial signaling here was simple: if a black intellectual thought as Republicans did, then these thoughts could not be anti-black.

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’s story is similar to that of Loury—except that Thomas has not offered public reflections on the role of race in his ascendance, and he has stuck with the conservative program. For this, he has been richly rewarded. In his memoirs, Thomas recounts a phone call from the Office of Presidential Personnel in 1981. The caller invited Thomas to take a position as assistant secretary for civil rights in the Department of Education. Thomas was unenthusiastic, in part because he wanted the Department of Education to be abolished. But that was not the only reason for his reluctance: “I had no background in that area, and was sure that I’d been singled out solely because I was black, which I found demeaning.”35 He chose to accept the position anyway, however, because he was interested in racial issues.

Thomas seemed to get over his concern that he was being offered government appointments on racial grounds. His memoirs make no mention at all of the fact that the Reagan administration chose him to be chair of the EEOC—after the Senate had rejected another black conservative candidate, Detroit lawyer William Bell, following criticism from civil rights groups.36 This is all the more notable given that Thomas recalled that liberals were continually calling the Reagan administration racist. He himself urged more appointments for blacks, but offered no rationale for it, saying only that it was “important.”37

Thomas’s account of his elevation to circuit court judge and later to the Supreme Court also reveals little sense that his race played much of a role in his advancement, even though there is a history of race, ethnicity, and other demographic variables influencing court appointments, and even though President George H. W. Bush chose Thomas to replace Thurgood Marshall, the only other black justice in Supreme Court history. According to his memoirs, Thomas asked White House counsel Boyden Gray whether race was the deciding factor in his nomination. According to Thomas, “Boyden replied that in fact my race had actually worked against me. The initial plan, he said, had been to have me replace Justice (William) Brennan in order to avoid appointing me to what was widely perceived as the court’s ‘black’ seat, thus making the confirmation even more contentious.” Brennan had retired earlier than expected, and the Bush administration had felt Thomas, who had been a judge only a few months, needed more seasoning on the circuit court (nevertheless, Bush would wait less than two years before putting Thomas on the Supreme Court).38

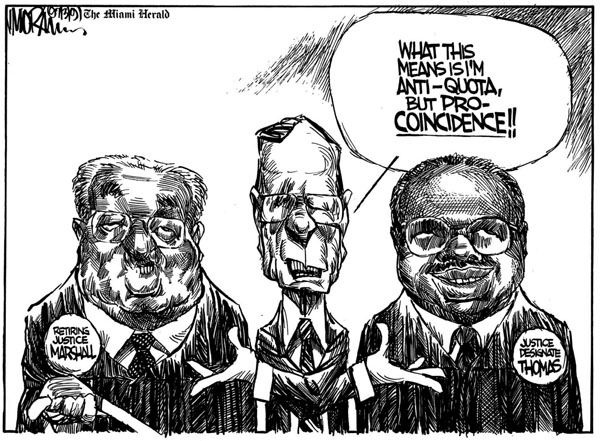

Thomas’s mostly color-blind account of events surrounding his appointment contrasts sharply with the public discourse of the time. Lauding Thomas’s self-help ideology, conservative columnist Cal Thomas wrote, “It will be amusing to watch the civil rights establishment trying to oppose him on such a clearly all-American agenda.”39 Pulitzer-Prizewinning political cartoonist Jim Morin drew Bush standing between Marshall and Thomas, pointing to each across his chest with opposite hands, and saying, “What this means is I’m anti-quota, but pro-coincidence!!”40 The Brookings Institution’s Thomas Mann said, “I think that Bush has moved very cleverly,” but “it is disingenuous for Bush to argue that race was not a factor in his appointment of Thomas.”41 The U.S. News & World Report wrote, “The president, despite his frequently stated opposition to quotas, was acutely conscious of the need to preserve black representation on the court after Marshall’s retirement. Bush also wanted to show sensitivity to black concerns after opposing Democratic civil rights legislation as a ‘quota bill’ earlier this year.” The right-leaning magazine also quoted a Bush adviser, who gloated that after confirmation, “‘the two highest senior black officials in the federal government will be Colin Powell [chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff] and Clarence Thomas. Both were named by a Republican president, and both cases suggest that the route to success is self-help and black pride, not dependence on white society.”42 Legal scholar Michael J. Gerhardt wrote in 1992 that Thomas “has done little, if any, memorable work” in any area outside of civil rights,43 and “no one took seriously the President’s characterization of Justice Thomas as ‘the best person’ in the country to serve on the Court.”44 Perhaps the most extreme criticism came from Senator Bill Bradley, who compared Bush’s use of race in the Thomas nomination to a campaign ad used against Michael Dukakis that highlighted the saga of murderer Willie Horton, who raped a woman while on a Massachusetts furlough program. Bradley argued that Bush’s “tactical use of Clarence Thomas, as with Willie Horton, depends for its effectiveness on the limited ability of all races to see beyond color and, as such, is a stunning example of political opportunism.”45

A scholarly account of the appointment reveals the predictable considerations of racial signaling. Bush asked staff to concentrate on finding “non-traditional” candidates, and they provided the names of two appeals court judges: a Latino, Emilio M. Garza, and Thomas. Chief of Staff John Sununu supported Garza on the theory that Garza’s appointment might help win Latino votes, while appointing Thomas would not entice the overwhelmingly Democratic black voters to cast ballots for Republicans. White House Counsel C. Boyden Gray supported Thomas because of Thomas’s solidly conservative views. Bush went with Thomas because of his conservatism, which would satisfy the most conservative Republicans, and also because Bush anticipated that being African-American would ease the path to confirmation of a conservative nominee.46 It would be hard to oppose Thomas after Scalia and Kennedy had made it through the confirmation process, and African-Americans would have an especially hard time opposing him. Another factor was that the NAACP had privately said they would not oppose Thomas.47

By the mid-1990s, Republicans were regularly using racial realism while criticizing affirmative action. Oklahoman J. C. Watts, who in 1994 became the first black Republican member of Congress from a southern state since Reconstruction, experienced a totally unsurprising meteoric rise in the Republican Party. Watts was young, smart, possessed a warm personality, and was a gifted speaker, but he had little experience and no leadership position in the House. Nevertheless, the party gave him opportunities to maximize his visibility to voters. As USA Today reported in 1998, “A party seen as hostile to minorities meanwhile basks in a symbol of diversity who is also a bedrock conservative,” and “Republicans showcased Watts at their national convention in 1996 and chose him to give their response to the president’s State of the Union message in 1997.”48 It was the first time that an African-American gave the response to the State of the Union address. When the new Republican congressional majority made a move to retrench affirmative action, Watts played a key signaling role. He was a coauthor with senate leader and eventual GOP presidential nominee Robert J. Dole (R-KS) of a Wall Street Journal op-ed calling for an end to the controversial policy.49 Like Thomas, Watts hardly reflects in his memoirs on the role of race in gaining him these high-profile opportunities.50

Figure 1. Cartoon by Jim Morin shows George Bush during the nomination process for Justice Designate Thomas. Courtesy Jim Morin / The Miami Herald / Morintoons Syndicate.

Following Clinton’s unprecedented efforts at implementing diversity in his administration, which included African-Americans but also multiple Latinos and women, plus one Asian-American (which he called having a cabinet that “looks like America”51), the administration of George W. Bush went even further. He appointed consecutively two African-Americans to one of the most prestigious jobs in the administration, Secretary of State, with Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s National Security Advisor, succeeding Colin Powell (who had been Reagan’s National Security Advisor and also Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under George H. W. Bush and Clinton). Bush also appointed African-Americans as secretaries of Housing and Urban Development (Alphonso Jackson) and Education (Rod Paige). Latinos ran the Commerce Department (Carlos Gutierrez) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development after Jackson (Mel Martinez), and Asian-Americans oversaw Labor (Elaine Chao) and Transportation (Norman Mineta, who had been Secretary of Commerce in the last year of the Clinton administration).

The Impacts of President Obama and the Growing Latino Vote on GOP Racial Signaling Strategy

Two circumstances—the election of America’s first president with (known) African ancestry, and the rapid growth of Latino and Asian populations—have appeared to increase pressure on Republicans to signal openness to nonwhites.52 The Republicans installed the African-American former Lieutenant Governor of Maryland, Michael Steele, as Chair of the RNC. Steele bested another African-American, Ken Blackwell, the former Secretary of State of Ohio, as well as four white candidates. Though most party leaders (typically) downplayed the role of race in the process, some in the party openly celebrated the benefits of having Steele at the helm. Jim Greer, the chair of the Florida party, told the New York Times, ‘‘There certainly is an advantage of a credible message of inclusion if you have a minority as chairman.’’53 Andy McKenna, chair of the Illinois Republican Party, declared that Steele would “show our ideas are good for people across the economic spectrum, across the ethnic spectrum,” and Kevin DeWine of the Ohio party predicted Republicans would see Steele’s election “as a significant sign of change.”54 Joanne Young, a member of an advisory committee for the Washington, DC Republican Party, told the Washington Post, “He is very truly the representation of the party of Lincoln…. He will reach out to women and moderates. It’s a very positive message for the country to have an African-American who is at the helm of the Republican Party.” Upon election, Steele himself admitted: “We have an image problem,” because “We’ve been misidentified as a party that is insensitive, a party unconcerned about the lives of minorities…. That day is over.”55

Steele’s rise coincided with that of another nonwhite Republican, Louisiana Governor Piyush “Bobby” Jindal. Like J. C. Watts, Jindal was smart, young, and a gifted speaker when Republicans tapped him to represent the party following a Democratic president’s State of the Union address. Choosing a white Republican (which, not counting four Cuban-Americans, was the only option if they were to choose a speaker from Congress) would, it was apparently believed, have made for an unpleasant contrast to Obama. Much of the enthusiasm for Jindal’s role was, accordingly, due to his Asian immigrant roots. A GOP strategist ticked off Jindal’s positive attributes—and then added, “The Republican Party very strongly wants to have a new look…. They’re saying, ‘We’re not just a party of old white guys,’ and he’s part of that appeal.”56 Republican consultant Alex Castellanos told New York magazine that Jindal and Steele “look like the future.”57

Latinos became the largest minority in 2009, and this, too, had impacts in American politics and racial signaling strategies. In a replay of the strategy of finding African-Americans to take stands against policies typically identified as benefiting that group, in 2010 the GOP was showcasing Latino candidates to counteract the party’s strong anti-illegal immigration stance. Republican leaders have gone out of their way to recruit Latino candidates to represent conservative white districts around the country, including Georgia and North Carolina.58 The 2010 Republican candidate for the governorship of New Mexico, Susana Martinez, was an outspoken opponent of illegal immigration, arguing that undocumented immigrants should be prohibited from getting driver’s licenses, and she also defended a controversial Arizona law that required local police to detain suspected illegal aliens. She explained to the Wall Street Journal, “There is a stereotype that Hispanics must be in favor of different policies than I am expressing, and that’s not what I’m finding at all.”59

The Latino backgrounds of even a few candidates were a plus for the national party as well. Whit Ayres, a Republican pollster, told the Washington Post, “Republicans need to be clear that they not only want but welcome Hispanics into the Republican Party, and having … prominent, successful Hispanic Republicans sends that message loud and clear.”60 Similarly, Ayres told the Wall Street Journal: “Having Hispanic candidates be successful on the Republican ticket and visible nationally will go a long way toward rectifying … [the] damage” caused by the party’s restrictionist stance on immigration.61 Immigration restrictionist Congressman Lamar Smith (R-TX) penned a Washington Post op-ed in which he argued that opposing the legalization of undocumented immigrants was not hurting the GOP with Latino voters, while at the same time he emphasized the signaling power of the election of anti-legalization Latino governors, congressmembers, and a senator.62 In the run-up to the 2012 election, some conservatives openly discussed the strategy of using Cuban-American Marco Rubio as a running mate to lure Latino voters.63

Following the 2012 election, where Republicans held their majority in the House but failed to take the Senate or unseat Barack Obama, Republican leaders began a period of analysis of the failure of their presidential candidate, Mitt Romney, to attract more than 27 percent of the Latino vote and 26 percent of the Asian vote. Reince Priebus, the replacement of Michael Steele as head of the Republican National Committee, created a “Growth and Opportunity Project” to research plans for the future of the party. Much of its report focused heavily on demographics and strategies to reach nonwhites, women and youth. Despite the new tone of urgency, the report called for more of the same racial realism strategies the party had used for decades. It recommended the creation of a Growth and Opportunity Inclusion Council, which would (among other things) “train and prepare ethnic conservatives for media presentations nationally and locally…. This new organization should encourage governors to embrace diversity in hiring and appointments to the judiciary, boards and commissions.”64 The report also recommended that the RNC “hire Hispanic communications directors and political directors for key states and communities across the country” and “improve on promoting Hispanic staff and candidates within the Party,” using them in the media, and showing them “involved in political and budget decisions.”65 The report recommended similar actions for Asian-Americans and African-Americans. A section on “candidate recruitment” was heavily focused on finding nonwhite Republicans, as well as women.66 The party quickly began implementation of the report’s recommendations, hiring, for example, two Asian-Americans, Jason Chung and Stephen Fong, to focus on communications and grass roots campaigns aimed at Asian-Americans.67

The Latino ascendance has impacted Democrats as well. The Democrats’ use of racial signaling in political appointments remains conventional, following the logic of patronage politics similar to that exemplified by Big Bill Thompson at the start of this chapter or Johnson’s appointment of Weaver. Because Democrats receive the majority of Latino votes (as well as the majority of black and Asian votes, though there are ethnic variations within the Latino and Asian blocs), they continue to offer appointments to members of these groups either to reward them for their support or because organizations acting on behalf of these groups pressure the Democrats to make these appointments. For example, the Congressional Hispanic Caucus lobbied Obama to choose a Latino to replace Supreme Court Justice David Souter when he announced his retirement. The Caucus explained, “appointing our nation’s first Hispanic justice would undoubtedly be welcomed by our community and bring greater diversity of thought, perspective and experience to the nation’s legal system.”68 Other groups lobbying Obama for a Latino Justice were the National Hispanic Leadership Agenda, the Hispanic National Bar Association, and a group calling itself Hispanics for a Fair Judiciary.69 After Obama chose Sonia Sotomayor for the Supreme Court, the New York Times was able to report on the wide ripple effect in a satisfied Latino community, though there was also skepticism that one high-profile appointment was enough to earn votes.70 Obama allegedly sought diversity on the Court and especially a Latino justice well before the appointment, and he did appear to get a slight bump in support.71

Racial realism showed itself in the Sotomayor nomination in yet another way, when it became known that she had touted her own racial (and gender) abilities relative to a white male judge in a 2001 speech. She declared, “I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life.”72 Critics pounced on the statement, and it became an issue in the confirmation process. Perhaps most prominently, conservative commentator Rush Limbaugh and former Republican Speaker of the House (and 2009 Republican candidate for president) Newt Gingrich called Sotomayor’s comments racist. Gingrich wrote, “A white man racist nominee would be forced to withdraw,” and “a Latina woman racist should also withdraw.”73 Meanwhile, Latino support for congressional Republicans after the nomination fell from an already dismal 11 percent approval to 8 percent.74

Is Racial Realism Prevalent in Federal Appointments?

The foregoing should suggest that political elites regularly consider the race of their appointees and that they strategically manage racial signaling to achieve their electoral goals. Political scientists have only begun to study this phenomenon, however, so it is difficult to make broad, verifiable statements about how common this kind of racial realism is in appointments. The one area where it has been studied is in judicial appointments, and here most scholars are in agreement that appointments are made following racial-realist principles. Research has shown that presidents making appointments to the federal bench regularly consider race, as well as religion and gender.75 While Johnson was the first to appoint an African-American to the Supreme Court, it was Jimmy Carter who made racial as well as gender diversity a major goal of his overall judicial appointment strategy, and established the strategy as normal in presidential politics.76 Moreover, senators appear to believe that a Supreme Court Justice’s race matters to their electoral fortunes: Democrats were more likely to support the Clarence Thomas nomination if they had sizable black constituencies, and this was especially true if they were facing a reelection campaign.77

More recently, studies have shown that appointments of minorities to district courts correlate with the percentage of minorities in the voting age population of a district, as well as with the numbers of potential minority campaign donors.78 At the circuit court level, one study found that presidents’ decisions to appoint a minority judge correlates with ideology (conservatives being less likely to appoint minorities at this level) and whether a state in the circuit has a minority representative in Congress,79 but it is important to note that there are fewer minorities who share a conservative than a liberal ideology (and Republicans will rarely appoint liberals in order to pursue racial signaling goals). An analysis of George W. Bush’s appointment record not surprisingly found that he pursued racial and gender diversity goals when they fit with his ideological commitments.80

Does the Race of Government Officials Matter?

One important caveat must be kept in mind as we assess the effectiveness of racial realism in the top echelons of government: namely, that comprehensive evidence is difficult to obtain, and this for the simple reason that despite their growing presence in the electorate, there are still few nonwhite leaders in government, especially Asian-American leaders.81 Nevertheless, social scientists have studied this subject extensively, so much, in fact, that it is very difficult to summarize the massive number of findings on different racial groups and their impact on different aspects of government and politics.

The field can be divided into research on elected officials and research on appointees or bureaucrats. While my main interest is how political elites strategically use race when they “hire” and place different people through the appointment process, it is important to note that a very large body of research has also explored the ways in which the racial identities of elected officials themselves have effects on and importance to voters. The focus of this research has been on what political scientists call “descriptive representation” (when minority groups are represented by members of their own groups) and “substantive representation” (when those who represent minorities actually vote or take other actions that are in the minorities’ interests). This latter concept roughly conforms to what I have called throughout this study “racial abilities.”

Regarding this research on race and elected officials, it presents us first with evidence on the ways race matters to voters. One review of the literature found most evidence that whites and blacks both tend to prefer candidates of their own race, that whites tend to prefer lighter blacks over darker blacks, and that they say that they vote for African-Americans more than they actually do. Experimental study designs also show that race matters to voters. One experiment gave white subjects identical descriptions of political candidates, varying only the race of one of the candidates, and found that whites were more likely to vote for candidates when they were white rather than black. For these reasons, it is not surprising that only four blacks have ever served in the U.S. Senate, and only two since Reconstruction.82

Then there is evidence regarding how the race of elected leaders affects the attitudes or behavior of the public. One study has shown that blacks living in regions where the mayor of the largest city is black are more politically informed: they are more likely to be able to name their local school board president, their representative in Congress, and their state governor. Moreover, those blacks who are more informed tend to be more active. Participation in voting, campaigning, civic associations, and contacting government officials goes up when there is a black mayor. Having blacks in office also leads black citizens to be more trusting of government. Black mayors have some opposite effects on whites: they are less likely to know their school board president or representative in Congress than they would be if the mayor were white.83

Researchers have found racial signaling effects at varying levels of government. Blacks are more likely to approve of the job their member of Congress is doing if that member is black, and blacks represented by blacks tend to know more about their representative than when they are represented by other races.84 Other evidence shows that black citizens are more likely to contact their legislative representative when that representative is black rather than white. White citizens are more likely to give favorable assessments to white representatives than nonwhite, and also are more likely to contact same-race representatives.85

Research on the 2008 election of Barack Obama has found that the election was the most racially polarizing in American history, as he especially attracted racial liberals and repelled racial conservatives.86 Black approval of Obama’s performance in office seems to be linked to his race, as blacks, regardless of their party and of their opinions on his policies, show more approval of Obama than do whites and more than blacks showed for President Clinton.87

There is also growing literature on what has become known as the “Obama Effect,” which essentially refers to the power of Obama’s racial signaling to change attitudes or other social dynamics. This research has identified a variety of effects linked to Obama, his race, and the context of presidential power, expertise, leadership, and family in which he is continually portrayed. For instance, there is evidence that Obama’s election has had positive effects on racial attitudes. One study found that exposure to Obama via television led to reductions in anti-black prejudice among conservatives, who had the most prejudice to begin with. This was true even when the exposure came via conservative television programs critical of Obama.88 On the other hand, an experimental study found that priming subjects to think about Obama was associated with no change in some measures of bias and actually seemed to produce increases in others associated with resentment of African-Americans.89 Along these lines, an analysis of discrimination law cases found that Obama’s election had no reduction in filings, and in fact charges of racial harassment discrimination began to identify individuals who “made references to Obama in ways that demonstrate racial animus against blacks.”90 One study found that black students improved their performance on standardized tests in periods right after extensive media coverage of Obama (specifically, his convention speech and his election), though a study using an experimental method found no difference in test performance between black students prompted to think about Obama before taking the test and those who were not so prompted.91

A more established line of research indicates that black legislators have racial abilities, showing more responsiveness to black interests than do white legislators. Though there are some prominent exceptions in the scholarly literature,92 one review concluded that much evidence indicates that black lawmakers are “far more likely than white Democrats to reflect the interests of their black constituencies” and are “also more likely to propose legislation consistent with African-American policy preferences.”93 Black legislators also more often locate their offices near the African-American community and staff these offices with African-Americans who have ties to the community, and they prove more successful in delivering federal funding for local projects that benefit blacks, including funding for historically black colleges and universities.94 Black and Latino members of Congress are also more likely than whites to exercise oversight of federal agencies in congressional hearings that deal with race or social welfare issues.95 Another racial effect relates to employment: a study of Southern communities found a correlation between the numbers of blacks on the city council and blacks in local government jobs.96

The evidence on Latino racial signaling and abilities is more mixed because of the heterogeneity of Latinos. Experts, activists, and Latinos themselves disagree on the meanings of the “Latino” or “Hispanic” categories, as both are made up of complex groupings of persons from Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America, and South America.97 Here is how one leading expert on Latino politics summed up the state of knowledge in the early 2000s: “As was true in 1990, in 2004 Latinos do not behave as a political group united by ethnicity. Latinos do not see themselves as united politically and they report that they will not vote for a candidate because of shared ethnicity.”98 One study has found that a candidate’s Latino identity has only an indirect impact on Latino voters.99 Moreover, a study of California and Texas found that having Latino legislators in the state legislature or the House of Representatives was associated with only a modest decrease in Latino political alienation.100

However, there are many recent studies showing that Latino identities do matter when it comes to filling upper-level federal positions and positions in more local governments. Districts with Latino populations, for example, are more likely to elect Latino candidates for state and congressional offices.101 A survey that asked respondents how they would vote in an election between Latino and non-Latino candidates (including scenarios where the Latino was of the opposite party of the respondent) found that Latinos with high degrees of ethnic attachment were more likely to support the Latino candidate when no party label was included, and somewhat more likely to vote for the Latino of the opposite party.102 This study also analyzed voting data in five mayoral elections in Los Angeles, Houston, New York, San Francisco, and Denver, as well as state legislative and congressional elections, and found that areas “with larger proportions of Latino registrants are more likely both to evidence high turnout rates when a Latino candidate is running for office and to vote for that candidate.”103 The reason for the higher turnouts may be not only a response to candidate race; Latino candidates in this study were found to make greater efforts to mobilize Latino voters than other candidates.104 While having a Latino representative or executive in office may have positive effects on voters (and an interview study found that Latinos in office tend to believe they have racial abilities to better represent Latinos105), there is little evidence that Latinos in office represent Latinos differently than non-Latinos.106

Studies of racial signaling or racial abilities on the part of appointees are far fewer, but they tend to show impacts. A survey experiment examined how same-race appointees affected three different measures of African-American and Asian-American racial identity: perceptions of shared racial fate, closeness to members of their own race, and a racialized political identity among blacks and Asian-Americans. Researchers showed half the respondents pictures of Democratic and Republican cabinet officials of their own race and included text highlighting their racial background (Ron Brown and Rod Paige to African-Americans; Norman Mineta and Elaine Chao to Asian-Americans), while the control group saw no pictures. For both African- and Asian-Americans, the individuals who viewed the same-race cabinet members were more likely to respond affirmatively on all of the three measures of racial identity.107

Data on the racial signaling effects of nonwhite judges, a group of appointees with high status but low visibility, are mixed. For example, a study of the effects of black judges in Mississippi on black Mississippians’ attitudes of the fairness of the state courts showed little impact.108 However, a study using an experimental survey technique has shown blacks to be more likely to view judiciaries as legitimate when they have black judges; this was true of even conservative blacks. Whites, including liberal whites, showed less support for a judiciary where blacks were well represented.109 A study of Texas Latinos’ attitudes toward the U.S. Supreme Court before and after the appointment of Latina Sonia Sotomayor showed an increase in approval of the Court as well as betterthan-expected knowledge of the appointment, but showed Sotomayor’s appointment having little effect on the attitudes of non-Latino whites.110

Nonwhites may support appointments of nonwhite judges for a variety of reasons, but the jury is still out on whether nonwhite judges have racial abilities that white judges lack (e.g., the “wise Latina” that Justice Sotomayor had celebrated, discussed above). Evidence exists both for and against the existence of racial abilities in judging. Supporting the view that there are no racial abilities in judging, a comparison of sentencing in trials presided over by a black judge with those where a white judge presided found no significant differences, as both black and white judges tended to impose harsher sentences on black defendants than on whites.111 Other studies have found no differences in sentencing, though the race of attorneys may be an intervening variable.112 A study of Clinton appointees also found no difference between black and white judges’ rulings in cases involving black issues.113

But other studies show that the race of the judge can matter in the administration of justice. A study of Carter’s black appointees found that they cast 79 percent of their votes in favor of the criminally accused, while Carter’s white appointees voted similarly only 53 percent of the time (oddly, however, this same study found almost no difference between the rulings of black and white judges in race discrimination cases).114 An analysis of black and white judges’ decisions on criminal search and seizure—a potentially better measure of racial abilities because judges have more discretion on these cases—found that black judges were more receptive to allegations of misconduct by law enforcement officials than were white judges.115 Another study of black and white judges’ decisions to incarcerate in a large American city found, after controlling for factors such as a defendant’s prior criminal record, that white judges were less likely than black judges to send white defendants to prison, though black and white judges treated black defendants with equal severity. On the other hand, black judges tended to be more lenient to black defendants on other measures of sentence severity, such as duration of jail time and opportunities for probation.116

In short, though the results are not consistent and there are likely differences between groups, there is considerable evidence that party leaders are wise to manage the racial signaling of elected officials and appointees. The race of government officials does often impact the public’s attitudes. There is also considerable evidence that the race of government officials matters in how they do their jobs. In other words, voters have good reason to care about the race of government officials, and party leaders have good reason to use the racial-realist strategy extensively.

Policing While Black: Racial Realism and the Enforcement of Law

Could the government’s most basic duty—the provision of law enforcement, public safety, and justice—require attention to the race of law enforcement officers? The belief that good police work requires racial realism has a long history in the U.S. and may be more entrenched now than ever. Advocates speak from positions of authority, such as federal commissions or government positions, and also come from grass roots nonwhite communities. They argue that officers vary by race in their ability to police a neighborhood, or that the race of an officer can communicate a powerful signal of self-sovereignty because when the police look like the policed, there is at least an appearance of fair law enforcement.

Race Matching of Police: An American Tradition

Though current practices and advocacy reflect a departure in terms of scale and diversity, police departments in America have long hired and placed officers on the basis of race. Early moves in this direction were intended to produce effective policing, but they were more about managing racial signaling to whites than to nonwhites. In the nineteenth century, city governments doled out police jobs as rewards for political loyalty, and blacks received these patronage rewards on occasion. But they faced serious problems: some white officers, as well as white citizens, were so offended by the idea of a black man in a uniform—a black man with authority—that black officers faced violence, including physical assaults. Departments therefore segregated black officers and sent them to police black neighborhoods, because it was only there that they could work without disruption.117 As late as the 1950s, the two African-Americans on the police force in New Orleans could only patrol black neighborhoods, could not wear uniforms, and could not arrest whites.118

Yet even in these early years there were some who believed being black made some officers better qualified to enforce the law in black neighborhoods. This perception of racial abilities would become more prevalent among government officials and scholars over the next few decades.119 For example, as early as 1931, a report by the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement stressed the benefits of recruiting diverse police officers familiar with the language, habits, and cultures of ethnic groups.120

It was the racial violence of the 1960s, however, that boosted racial realism in policing to the national agenda. Studies of the violence almost always found that even in the best of times, there was a disconnect between white police forces and black neighborhoods, with blacks often feeling that they were under foreign and hostile occupation. At worst there was brutality and other abuses of power by police.

It was often a rumor of police brutality that set off the 1960s megariots (many called them rebellions) in the urban North, including the riots in Harlem and Rochester in 1964, in the Watts section of Los Angeles in 1965, and in Detroit and Newark in 1967. There were also hundreds of other riots/rebellions in cities big and small. Some caused tens of millions of dollars in property damage, almost all of it in predominately black neighborhoods. Thousands were injured and/or arrested.121

Observers increasingly saw racial mismatches between police and neighborhoods as a major part of the problem. Lyndon Johnson’s aides communicated from the front lines that the whiteness of the police and the resulting lack of racial understanding were creating tensions in black communities and called urgently for more black faces on the police and National Guard forces trying to maintain order.122 Whether the strategy was racial signaling, racial abilities, or both was unclear, but it was certainly more an instance of racial realism than affirmative action when New York installed an African-American to head the Harlem precinct after the riot there, and created a new post of “Community Relations Coordinator” in Harlem. The African-American officer appointed to that post was asked by the New York Times if race was a factor in his appointment, and he replied, “Candidly, I suppose it was. And that’s all right with me. The important thing is I think I can improve the situation there.”123

Similarly, in 1966, New York City used a $2.9 million federal grant to recruit one thousand disadvantaged blacks and Puerto Ricans to the police force. According to the New York Times, this effort aimed to “lessen the odds of race rioting.”124 A New York police chief explained, “The recruitment of Negroes into the department is not simply opening up jobs to all members of the community, but also a political necessity for pacifying the Negro community and winning the support of its members.”125

A year later, Lyndon Johnson’s President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice extolled the value of racial signaling in the police force. Calling for “a sufficient number of minority-group officers at all levels of activity and authority,” the report stated that “a department can show convincingly that it does not practice racial discrimination by recruiting minority-group officers, by assigning them fairly to duties of all sorts in all kinds of neighborhoods, and by pursuing promotion policies that are scrupulously fair to such officers. If there is not a substantial percentage of Negro officers among the policemen in a Negro neighborhood, many residents will reach the conclusion that the neighborhood is being policed, not for the purpose of maintaining law and order, but for the purpose of maintaining the ghetto’s status quo.” Moreover, if this effort was to show an advance over the old policy of a segregated police force, it would need to be balanced by a strategy of placing black officers in white neighborhoods as well.126

This report also cited a need for the racial abilities of black officers, explaining that a “lack of understanding of the problems and behaviors of minority groups is common to most police departments” and is a “serious deterrent” to effective policing. The report concluded that “a major, and most urgent, step in the direction of improving police-community relations is recruiting more, many more, policemen from minority groups.”127

A better-known federal government report, though one that came to similar racial-realist conclusions, was that of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, more popularly known as the Kerner Commission. As it did for journalism, the report also gave prominent support to racial realism in policing. Black officers have special abilities, the report argued, because they “can increase departmental insight into ghetto problems, and provide information necessary for early anticipation of the tensions and grievances that can lead to disorders.” In addition, “There is evidence that Negro officers also can be particularly effective in controlling any disorders that do break out.”128

Other official bodies have fostered the notion that effective policing requires racial realism in hiring and placement. A 1973 report by the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, for example, added its voice to previous commission findings, stating that “minority officers are better able to police a minority community because of their familiarity with the culture.”129

At around the same time, Congress was debating amendments to Title VII that would expand its coverage to government employment. While Senate and House reports noted the value of having nonwhites in a variety of government positions, law enforcement received special attention. Though the bill supported a classically liberal approach, the Senate Report stated in 1971, “The exclusion of minorities from effective participation in the bureaucracy not only promotes ignorance of minority problems in that particular community, but also creates mistrust, alienation, and all too often hostility towards the entire process of government.”130 The House echoed this theme: “The problem of employment discrimination is particularly acute and has the most deleterious effect in these governmental activities which are most visible to the minority communities (notably education, law enforcement, and the administration of justice) with the result that the credibility of the government’s claim to represent all the people is negated.”131

Nearly twenty years later, the message was the same following some incidents of police brutality in Los Angeles, most notably the beating of Rodney King, which was caught on grainy, graphic video. A report on the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department called for better nonwhite representation on the force and better utilization of the racial abilities of nonwhite officers. It argued, “These officers have important knowledge, experience and insights regarding effective and sensitive community-based policing…. Their cultural knowledge and communication skills could be invaluable in defusing tensions on a street corner or in a jail cell…. Many minority officers have a broad historical and societal perspective that is most useful in the Department’s efforts to increase the sophistication and effectiveness of its community-policing efforts.”132

Though conservatives can be suspicious of racial realism in policing,133 George W. Bush’s Justice Department declared in 2001: “A diverse law enforcement agency can better develop relationships with the community it serves, promote trust in the fairness of law enforcement, and facilitate effective policing by encouraging citizen support and cooperation.” More practically, it advised: “Law enforcement agencies should seek to hire and retain a diverse workforce that can bring an array of backgrounds and perspectives to bear on the issues the agencies confront and the choices they must make in enforcing the law.”134

While many advocates speaking on behalf of the government have long supported racial realism in policing, local groups advocating on behalf of nonwhites have done so as well.135 In Brooklyn in 1964, the head of a group called the African Nationalist Pioneer Movement stated: “The assignment of more Negro patrolmen to the Bedford-Stuyvesant area will go a long way to improve community relations with police.”136 When the city put a black officer in charge of its largest station in Harlem, one civil rights leader remarked in 1966 that the effort “has made a dramatic difference. It’s more difficult for the inhabitants of Harlem to look upon the police as their enemy when he’s the same color as they are.”137 The most common pattern for advocacy of this kind would be an egregious incident of police brutality spurring calls from local civil rights leaders and African-American ministers for an increased black presence on the ground and in the police administration. For example, after the NYPD’s 1997 beating and torture of Haitian immigrant Abner Louima, the Giuliani administration worked with civil rights groups on a plan to move more black police officers to the Brooklyn precinct where the torture occurred (see below).

Some government officials have discussed the racial abilities and signaling benefits of African-American cops in African-American neighborhoods in interview studies. An analysis of black economic equality in the South found this perspective to be common. One white police chief explained, “We need to understand all citizens and can’t understand blacks without having blacks on the force…. It helps us deal with a culture we [whites] don’t understand. Blacks can be loud, boisterous, and in your face—most white officers don’t understand this.”138 A black officer in Quincy, Florida, explained, “When it gets ‘hot’ in black areas, they [blacks] want and need black officers…. Blacks frown on white police … they’re a symbol of white control and power. Black police are trusted more and have an attachment to blacks.”139

It should be noted that some police departments have sought to take advantage of racial abilities and signaling by means that stop short of hiring actual police officers. One strategy is to set up a “multicultural storefront” police station, staffed at least in part with “community service officers” who share the race and ethnicity of the community. This strategy allows for closer day-to-day contact and better relations, and arose partly in response from public pressure to “do something visibly special” for minorities.140 It also avoids the problem of finding minorities who can pass the various background and aptitude tests required for all police officers. Though not actually police officers, community service officers can act as cultural emissaries for the police department as well as signal some degree of self-sovereignty.

Another strategy is to institute advisory boards or appoint special assistants to the chief representing different ethnic and racial groups (as well as women, gays, and lesbians). These representatives are intended to serve as conduits of racial and ethnic culture and knowledge.141 Though citizen advisory boards were first set up in the late 1970s, and nearly 90 percent of departments in big cities have some citizen oversight for complaints, there is very little evidence as to whether or not the boards have an impact.142

The Evidence: Do Cops Have Racial Abilities? Does Racial Signaling Work?

Racial meanings are deeply woven into the interface between the police and the American public. Opinion polls reveal that blacks, whites, and Latinos have very different attitudes toward the police. These divergent opinions are especially apparent when the local headlines are dominated by an incident of police brutality. Shortly after the February 1999 police killing of Amadou Diallo, for example, a New York Times poll found that 72 percent of blacks and 62 percent of Hispanics, but only 33 percent of whites thought most officers use excessive force. Similarly, a June 1999 Quinnipiac College poll found that while only 25 percent of whites thought police brutality was “very serious,” 81 percent of blacks and 59 percent of Hispanics thought so.143

For some, this is already ample grounds to justify racial realism, but there is more direct evidence that specifically supports the strategy of racial signaling. Large numbers of blacks and Latinos appear to believe that a police officer’s race matters. A comprehensive survey study of attitudes toward race and policing conducted in 2002 found that nearly 70 percent of blacks thought there were differences between black and white police officers, while about 45 percent of Latinos saw differences, and about 38 percent of whites did. Almost half of blacks thought that Latino officers were different. About 30 percent of Latinos saw a difference between Latino and white officers, slightly more than whites did.144 This study also found that all three groups tended to see white cops as “tough/arrogant/insensitive” and black cops as “courteous/respectful/understanding,” though this pattern was most evident among black respondents.145 As one black respondent explained, “Black officers are more empathetic toward citizens. Black officers are taught, by virtue of their racial background, not to have bias or prejudice, whereas their white counterparts are not. Black officers are taught … not to lump everyone into one category…. White officers are taught that certain people always behave a certain way” (original emphasis).146 Though only 5 percent of blacks and 4 percent of Latinos wanted exclusively black and Latino officers, respectively, majorities of blacks and Latinos perceived race to matter enough that they preferred a racial mix of officers in their neighborhoods.147 These respondents lauded racially mixed policing teams as a means whereby nonwhites could educate whites on the job, and associated them with “impartiality,” “fairness,” and “checks and balances.”148 Given these attitudes, it is not surprising that one study found that Latinos in Houston would sometimes wait days until they thought they saw a Latino officer before they were willing to report a crime.149

There is also evidence that police officers themselves, as well as representatives of the nation’s police departments, believe racial realism is sound strategy in policing. For example, one interview study of fifty black police officers in the South found that the officers were “nearly unanimous” in believing they had special insights into problems.150 As one stated:

I really believe that African Americans, because we have always been on the receiving end of a lot of that stuff, that we really have a deeper level of understanding and compassion for other people. I really think it’s difficult for whites today to really see even the subtle vestiges of discrimination and prejudices…. I’m just saying that I think whites by and large have real difficulty, really being able to perceive and understand people who have to walk through that stuff, day after day after day.151

The argument that nonwhite officers can better understand nonwhite citizens also came up repeatedly in my research assistants’ interviews with police officials from around the country. Representatives from eight of the nine large city departments with whom we spoke cited a goal of racial balance in the police force, and four of the nine described the racial ability of understanding of people and neighborhoods as one of the reasons. The liaison to Asian police officers in a major West Coast city, for example, told us that his department tried to employ the same percentage of minorities as lived in the city, explaining that a major challenge for police in his city was “the trust factor,” and that a way to gain minority residents’ trust was to employ officers who “resemble them or understand their cultures and traditions.” He explained, “I think if we have a specific Latino officer in a Latino community that’ll actually go a longer way. The reason why is tradition, cultural, history, language. Those are just barriers that officer will not have to deal with.”152

We can see, then, that the public and many officers and their leadership seem to care a lot about race and offer support for at least some hiring and placing based on racial-realist principles. Are they right to do so?

Despite the claims of government bodies, civil rights leaders, city residents, and some police officers themselves that nonwhite officers have special racial abilities of understanding, social scientists have had trouble demonstrating that the phenomenon is real and has significant effects on policing. Here we have the benefit of two especially comprehensive, authoritative reviews of an extensive literature. First, legal scholar David Sklansky’s analysis of the research on police officer race shows, first, that there was an impressive increase in the percentage of nonwhite officers in major cities across the U.S. between 1967 and 2000. For example, New York City’s police force increased from about 5 percent to 35 percent minority; Chicago and Philadelphia both increased from around 20 percent to 40 percent; Detroit went from 5 percent to 65 percent minority; and San Francisco from 5 percent to 40. But when it came to the effects of this diversification, Sklansky found contradictory conclusions in the literature. He noted, on the one hand: “There are studies finding that black officers shoot just as often as white officers; that black officers arrest just as often as white officers; that black officers are often prejudiced against black citizens; that black officers get less cooperation than white officers from black citizens; and that black officers are just as likely, or even more likely, to elicit citizen complaints and to be the subject of disciplinary actions.” On the other hand, “there are also studies concluding that black officers get more cooperation than white officers from black citizens; that black officers are less prejudiced against blacks and know more about the black community; and that black officers are more likely to arrest white suspects and less likely to arrest black suspects.”153 Despite the mixed findings, Sklansky noted that scholars typically have viewed the evidence as indicating that officer race does not correlate with policing behavior.