CHAPTER 9

Playing the Other Side of the Table: Using Options to Reduce Volatility

Options are derivatives. Now, when most investors—especially low volatility investors—come across the word derivatives, the small hairs on the back of their necks immediately tense up and stand at attention. Low volatility? Derivatives? Can’t use those two words in the same sentence, can we? Yikes!

Gamblers, among others, know that there are two sides to the table. (Oh my, now we’re bringing gambling into the discussion?) I hear you cry—but have no fear, because gamblers know that they take one side of the table and the dealer, or house, takes the other. Most games are set up so that the money is made by the dealer off the risks taken by the gambler, while the gambler hopes to get lucky once in a while. The dealer (and the house) make most of the money off the risks the gambler is taking. In the leading strategy we will introduce in this chapter, known as selling covered calls, you’ll learn to play the house side of the table. In the two other strategies, you’ll learn ways to transfer your risk to someone else, as if you’re working with an insurance agent.

This isn’t a book about derivatives. If it were, we probably wouldn’t be including low volatility investing in the title. Instead, it is about reducing volatility in your portfolio. It turns out that if you take the right side of certain option plays, you can reduce risk or transfer your risk to someone else. You can bend the risk/reward curve in your favor, to protect yourself against long-tail events, turn potential volatility into current cash, and limit your overall downside risk.

Now, back to the word derivative for just a moment. A derivative is, according to Wikipedia, a “financial instrument which derives its value from the value of underlying entities such as an asset, index, or interest rate.” Derivatives are used most often to gain leverage or to hedge an investment; the price of a derivative does not move one-for-one with the price of the underlying asset. The world of derivatives is very complex; some derivatives trade on exchanges, while others, like swaps, are created by hand to service the needs of individual traders. We will focus on the most common and transparent exchange-traded variety of derivatives: equity (stock) and index options.

This chapter is about how to use derivatives to both boost income and hedge a portfolio, two objectives consistent with the premise of low volatility investing. We will explore three strategies:

• Buying put options to transfer downside risk

• Selling covered call options to earn current cash and reduce downside risk

• Buying call options on riskier stocks to reduce downside risk

Before examining those three low volatility strategies, we’ll first do another field guide—not a textbook—on put and call options, what they are, and how they work. Then, consistent with other parts of this book, we’ll explore the three different strategies above for using options to reduce volatility, with brief discussions of the mechanics and an example.

KNOWING YOUR OPTIONS: EQUITY, INDEX, AND OTHER

In the past 20 years, markets for listed or exchange-traded options have flourished. Options can be bought and sold for thousands of companies, large and small, and on specialized investments, like ETFs or even stock indexes themselves. The Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) is the largest trading venue, but there are others. The CBOE and its accompanying training and educational materials (http://www.cboe.com) are some of the best places to become familiar with options trading and trading strategies.

PUTS AND CALLS: WHAT THEY ARE AND HOW THEY WORK

Equity options come in two basic types: puts and calls. A call option is a contract to buy 100 shares of an underlying stock at a specific price on or before a specific date. The price is known as the strike price, the date is known as the expiration. So, if you buy one XYZ June 30 call, you are buying a contract allowing you to buy 100 shares of XYZ at $30 each anytime before the June expiration. What do you pay for that call option contract? Similar to insurance, you pay an amount known as a premium, determined by several factors expanded on below.

A put option works in the other direction: an XYZ June 30 put contract gives you the right to sell 100 shares of XYZ at $30 on or before the expiration date. When you buy a put, you’re buying protection against a downside move in the underlying asset.

What Are Equity Options Worth?

In the above XYZ June 30 call example, it is easy to see that the option has value at expiration if the stock closes above $30, and is worthless if the option closes below that level. Likewise, the XYZ June 30 put has value if the stock closes below $30. But what is the value of that option before the expiration? In April or May? That’s where much of the interest in options arises.

As we first saw in Chapter 5 in the discussion of the Black–Scholes option pricing model, the value of an option is determined by three factors: (1) the difference between the current stock price and the strike price, (2) the time to expiration, and (3) the volatility of the underlying investment. Obviously, if the current price of a security is above the strike price, the call option will have value—and more value the larger the difference—while the put option has no theoretical value.

But this value, sometimes known as intrinsic value, is just one factor. The longer the time to maturity, the more events can occur that will change the fortunes of the underlying investment, and the more chance the stock price has to exceed the strike price. Thus, an option expiring nine months from now has more possibilities than one expiring next week, and will be priced accordingly. Finally, the volatility, or variability, of the underlying stock influences the value of the option. A stock that regularly moves between 20 and 40 has more potential to produce winners for buyers of a 30 call than one that only moves between 28 and 32. Thus, the premium will be higher.

These factors play together in mathematically complex ways to drive the price of options. The Black-Scholes model calculates option values and, while useful, the behavior of prices is best understood by visual experience gained by examining the option chain over time.

Option Chains

An option chain is simply the list of available options on a security. For XYZ stock, there may be put and call options trading at 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, and 45. Whether or not an option is available depends on the interest of market makers and the market in general; there simply isn’t enough interest in a June 60 call for a stock trading in a 25 to 30 range for market makers to set one up. But as the price approaches 60, that option may appear, and it will appear if it becomes the next strike, that is, if the stock closes above 55.

To see what options are available for a stock, simply enter the stock ticker symbol in a financial portal or a broker site and look for an option chain or similar button, sometimes under an option tab.

Buying and Selling Options

Options are bought and sold through most online brokers. Today’s markets are highly liquid, and you can easily see what you’ll get if you sell or pay if you buy an option. Most trade in penny increments like stocks. Like stocks, brokers charge modest commissions for trading options contracts (1 contract = 100 shares in most cases); typical commissions run just slightly higher than stocks.

Most of the larger stocks have options that trade in monthly and quarterly expiration increments, and certain very active stocks now trade in weekly expirations. There are also longer-term options known as LEAPS, or Long-Term Equity AnticiPation Security contracts, which have expiration increments up to three years out, usually expiring in January of that year, as in a January 2015 call. Obviously, LEAPS will have a high premium for time value.

Most brokerage websites and, again, the CBOE website offer solid facts and instructional materials covering options, option trading, and option strategies.

WHAT DO I MEAN BY BENDING THE RISK/REWARD CURVE?

Can you fundamentally change the risk/reward profile of an investment? Not really. You can’t really change the external, internal, and personal risks of an investment or the world around it, other than by reducing exposure or avoiding the investment altogether. Just like buying car insurance, if you drive, you can reduce the probability of an accident by driving safely, but you can’t eliminate accidents altogether. However, you can change the financial outcome of that accident by buying insurance. Changing the financial outcomes in your favor is giving up something, usually money, to get something else: less volatility. That’s what I mean by bending the risk/reward curve. Here’s how options can help you do that:

• Buying puts is most like buying insurance: you’ll take a small loss (paying a premium) to protect against a larger one. It’s the most direct way to transfer your downside risk.

• Selling covered calls gives up large potential gains in favor of current income. You also get enhanced protection on the downside.

• Buying call options gives up a little cash now to achieve a large possible gain but avoids the risk of a major fall in the price of the underlying asset.

The rest of this chapter explores these three scenarios.

Buying Puts: An Investment Insurance Policy

Puts are the right to sell a given number of shares at a price by an expiration date. Buying a put is analogous to buying casualty insurance as you might for your house or car, but in this case it’s for an investment or for your entire portfolio. You’re transferring some or all of your risk to another party.

Here’s how it works. If you buy 100 shares of stock XYZ at $29.50, you might consider buying a June 29 put: the right to sell at $29 by the third week of June. That option gains intrinsic worth when XYZ drops below $29, and so far as your portfolio is concerned, gives you a downside floor for that stock. If the stock drops toward $29, the put value will rise, if it drops below $29, it is in the money and will rise equally with the fall of the stock. Thus, at $29, less the premium you paid, you’re 100 percent protected from further downside in the stock. If, in this case, you paid a $1.50 premium for the put, your downside floor is $27.50.

Figure 9.1 illustrates:

FIGURE 9.1

Put Buying Scenario

If you buy the put, you’re sacrificing the amount of the premium ($1.50 in this case) from your potential gain; that’s represented by area B on the chart. But you’re getting the downside protection shown as triangle A. If the stock drops to $27.50 or lower, the total value of your investment will remain $27.50. The chart illustrates the bending of the reward curve, from the steady rise to the right representing the stock performance with no options, to the knee curve, shown as a heavy black line, with options involved.

Put buyers are looking for peace of mind. The best time to buy puts is when everything feels good and the markets (or the stocks under consideration) are calm or, better yet, going up. During volatile markets, when most people think about buying puts, the premiums go up because everyone wants to buy puts. The downside of put buying is that premiums paid are real cash and will diminish your returns in a steady or rising market. And, like your car insurance, put options expire and you have to write the check all over again.

Many low volatility investors buy a few puts here and there just for some protection and peace of mind, usually far out of the money to avoid large cash outlays. Some buy puts covering the broader market—on stock indexes or on ETFs mirroring the stock indexes—such as the SPDR S&P 500 Trust (SPY). Recently, a nine-month put covering a 10-percent drop in the SPY ETF (from 155 down to 140) cost $3.80 per put—$380 per contract—and that price will vary according to the market volatility experienced at the moment. In guarding against a 20- percent drop, that $3.80 invested would rise to approximately $15 ($1,500) at expiration if the 20-percent drop occurred.

Some put buyers will take large positions far out of the money (perhaps, 20- percent below the current price) knowing that even a small move downward will drive the put price higher, especially if the down move happens well before expiration. A similar 20-percent down move (strike price $125) sold recently for $1.80. Their goal is to sell when the put moves from, say, $1.80 to $3.60, a 100-percent gain, which could be realized with a far smaller downward move early on in the cycle. They’re not only protected, they actually make money well before the put reaches an in-the-money state.

Over time, you might realize, especially in volatile markets, that, like most other forms of insurance, such portfolio insurance is expensive to buy. Most investors keep the cost down by buying deep out of the money puts tied to market indexes for that just-in-case scenario, but it also works if you’re in a stock that might exhibit some future volatility. All that said, buying puts can give you peace of mind, and it’s a worthwhile tool to have in your low volatility bag of tricks.

Selling Covered Calls: Turning Volatility into Cash

Earlier on I explained the purchase of call contracts, that is, contracting to buy 100 shares of XYZ at $30 by the third Friday of June. That trade wins if the price closes above $30 plus the premium paid for the option and brokerage commission by that date.

But what if you sell that call option? What if you collect a $1.50 premium for allowing someone to buy 100 shares of XYZ at $30 by June from you? Picture yourself as the green-visored dealer or insurance agent on the other side of the table and you get the idea. Collecting money by selling options becomes a major play for the low volatility investor, generating both short-term income and downside protection.

Here’s how it works: if you buy or own 100 shares of XYZ, you can sell a covered call option (covered by your ownership of the underlying security), usually for a strike price slightly above your purchase price. Why slightly above? It’s to get the most time and volatility premium, and to lock in a sale price, if the stock rises, above your purchase price. So you make money on the premium and on a small amount of price appreciation. As an example, if you buy or own 100 XYZ at $29.50 and sell, or write, a June 30 call at $1.50, you’ll collect $1.50 for the option plus the 50-cent gain from $29.50 to $30 if the stock appreciates to $30 or higher. You can do this for virtually any stock in your portfolio; you don’t have to go out and buy the underlying stock to do this.

What are you actually doing? You are giving up, or transferring, the potential of a larger future gain—say, if the stock rises to $34 or $35—for a more certain $1.50 collected at the time the option is sold. You’re giving up what might happen in favor of a certain current income: a proverbial bird in hand. At the same time, you still retain most—but not all—of the ordinary investment risk that the stock price might decline. Why not all? Because if the stock you bought drops to $28, you still break even, as you sold a call for $1.50 on shares bought or valued at $29.50. If the stock drops further, you lose, but again, the losses are offset by the premium collected plus transaction costs.

Picturing It

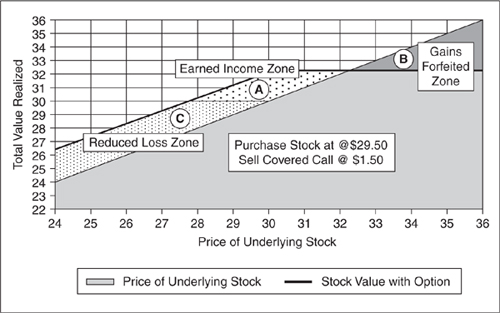

Figure 9.2 shows the above transaction graphically:

FIGURE 9.2

Covered Call-Writing Scenario

You buy or own 100 shares of XYZ at $29.50 and sell a June 30 call contract for $1.50. The slope of the straight up-and-to-the-right line shows the possible price outcomes with no options involved; you may realize any value along the sloping line.

By selling the option, you transfer a possibility for larger gains (B) to the option buyer, receiving the premium—current income—as compensation. The total value of this investment at different price points is represented by the heavy stock value with option line. This is the bent risk/reward curve.

If the stock price goes below $28, you’ll lose, but the losses will be reduced by the option premium collected (C). The parallelogram (A) represents the sweet spot of this transaction; that is, you pocket the income, forgo no larger gains, and incur no net depreciation of your capital. Most likely you turn around and repeat the transaction after expiration, collecting another premium for the next option period. If all goes right, sustained short-term income can be generated from your investments.

Writing Covered Calls in Practice

Writing covered calls is a strategy to improve returns by generating short-term income and to play defense by reducing losses. While most people think derivatives and options are risky and not for them, writing covered calls effectively reduces your risk by transferring it to someone else. However, gains forfeited can be significant, and if you take away the upside on all of your investments, particularly with options written for long expiration time frames, long-term performance can be affected, particularly since downside exposure is retained.

Writing covered calls on a limited portion of your portfolio is usually best. That way you preserve upside gains on much of the portfolio. Some stocks may be acquired just to write covered calls. This works especially well on more volatile, lower-priced stocks that command relatively high option premiums. Here especially, you’re turning volatility to your advantage: in this case, cash.

Among the best uses of covered calls is to write, or sell, them when underlying stocks already in the portfolio reach the high end of recognizable trading ranges. Selling calls on a portion—perhaps half—of the position captures some income while preserving some of the growth opportunity. In sum, covered calls can be used to harvest income and reduce downside risk, and to take some risk off the table from appreciated investments. This explanation doesn’t cover all nuances of this strategy, but it gives an idea of how this powerful tool is used, and with practice you’ll get good at it.

BUYING CALLS: A WAY TO REDUCE DOWNSIDE RISK

When you sell call options, there is a buyer, and that call buyer takes on risk by betting on the price appreciation of the stock (triangle B in the diagram above). As a call buyer, he or she buys an out-of-the-money call, and unless the stock rises past the stock price, they lose everything. But you also gain leverage—buy that XYZ June 30 call for $1.50, and if the stock moves to $35 (a 17-percent gain) you realize a value of $5, a more than 200-percent gain! So you get a larger possible reward, but you also do something else: you limit your downside risk. What’s the most you can lose? The $1.50: the price of the option.

So buying calls, in this sense, is a risk-reducing play. When you buy a call, the premium paid is the maximum amount risked. So, if you buy the XYZ June 30 calls at $1.50, the $1.50 is the maximum amount you can lose, whereas if you buy the stock outright, you can lose much, or even all, of the share value, $29.50 in the example. However, since the option has value only when the stock rises above 30, the probability of losing everything up to $1.50 is higher when you buy the option.

Many active investors buy calls when stocks get oversold or hit the bottom end of trading ranges, or when they are unsure about a particular investment. If it sounds like a good idea but they want less exposure to the downside, they can buy a call option. In that sense, buying the call option reduces the volatility simply by taking some of it away (as in prices dropping to $27, $26, $25, and so forth. Many also buy calls to get an active but limited downside, exposure) to a sector, a low- or negatively correlated hedge, like gold through the SPDR Gold Trust (GLD), or the broader market itself through something like the SPDR S&P 500 Trust (SPY).

Some active investors buy in-the-money calls as a simple alternative to buying shares. There are two reasons for this. First, if the stock drops or goes flat because of time value and the value of possibilities, these calls tend to decline in value more slowly than the underlying stock, providing some near-term downside protection. Secondly, some investors take an option position to avoid laying out the entire share price of the stock. Keep in mind that the main risk of options comes from the time element: when buying a stock, there is no time limit to achieve a gain—you own it forever—while with an option, the stock must perform in the given time. So while you risk less capital, you do pay a risk premium and you do incur the risk of time.

USING INDEX AND SECTOR OPTIONS

Index, sector, and ETF options extend the concept of equity options into market sectors and collective baskets of stocks. Thus, it becomes possible to buy or write calls on the S&P 500 as a whole, or virtually any other component of the market. As with equity options, low volatility investors can use these options to hedge against other investments and to generate short-term cash. There are options traded on major stock market indexes or averages, and options are also traded on many ETFs, thus giving active investors several ways to use options on major segments of the market.

ETF options allow investors to use them to hedge, generate cash, or gain long-term exposure to a market or market segment. As ETFs represent diversified portfolios, price movements are relatively modest compared to individual stocks, so premiums are relatively low. Still, covered call options can be used to generate some income against ETF holdings in a foundation or rotational portfolio and hedge against a downturn. You can protect from long-tail risks by buying ETF puts, or hedge with an inversely correlated investment like gold (the SPDR Gold ETF is a good vehicle).

ETF options are also a good way to play a vastly oversold market or sector. If the markets take a major spill, one can buy a call option on a SPDR S&P 500 ETF or the PowerShares QQQ Trust ETF (which covers the Nasdaq 100, known popularly as “cubes”) ETF. If the index rebounds, there is good upside potential; if it doesn’t, or if it declines further, you are only out the premium paid. Keep in mind that, as with all options, the greater the volatility, the higher the premium you’ll pay.

As you dig further into options and gain experience, there are lots of other strategies that can be used, mostly to be deployed as combinations of different types of options to reduce and transfer risk. Spreads, straddles, strangles, and others all play with timing, price, and trading ranges of underlying stocks to push the risk/reward curve around and produce income and/or gains and/or loss protection in the right circumstances. What’s been covered so far is probably enough; those more specialized strategies are more for traders and aren’t core techniques of the low volatility investor. Likewise, futures contracts and options on futures contracts may also enter the advanced lexicon, but it makes the most sense to stick with equity and ETF options to start out.

GETTING STARTED AS AN OPTION INVESTOR

The concept and use of equity options strengthen with time and practice. Investors new to the game should observe these instruments and their behavior over time, and begin with modest investments. Over time, each investor develops his or her own comfort zone for such issues as whether to trade in-the-money or out-of-the-money options, whether to sell covered calls or buy puts, and what time horizons to use. Investors learn price behavior over time, and to look for what makes sense in the context of their entire portfolios, without committing too much cash or locking in losses or giving away too much potential gain. Active option investors become familiar with certain stocks and their options, and many play short-term equity options on them each month. Others use longer-term options as stock surrogates or to hedge against major downside market activity. The cliché “to each his own” applies well to the strategic use of options.

KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Options are user-friendly, market-traded derivatives that give low volatility investors opportunities to reduce or transfer risk.

Options are user-friendly, market-traded derivatives that give low volatility investors opportunities to reduce or transfer risk.

![]() Options can be bought or sold (written) on equities, ETFs, or indexes, giving you ways to profit and/or hedge risk for individual stocks, sectors, or the entire market.

Options can be bought or sold (written) on equities, ETFs, or indexes, giving you ways to profit and/or hedge risk for individual stocks, sectors, or the entire market.

![]() Call options are contracts to buy a security at a set strike price at or before the expiration date; put options are contracts to sell the underlying security.

Call options are contracts to buy a security at a set strike price at or before the expiration date; put options are contracts to sell the underlying security.

![]() The premium is what you pay (or collect) for an option, and it works like an insurance premium.

The premium is what you pay (or collect) for an option, and it works like an insurance premium.

![]() By buying puts, you transfer the downside risk of a security or portfolio to someone else, and pay the put premium to do so.

By buying puts, you transfer the downside risk of a security or portfolio to someone else, and pay the put premium to do so.

![]() Selling covered calls allows you to transfer the opportunity for future gains to someone else, collecting the premium as profit and as an offset to your downside risk.

Selling covered calls allows you to transfer the opportunity for future gains to someone else, collecting the premium as profit and as an offset to your downside risk.

![]() Buying calls allows you to participate in a stock or ETF while limiting your downside risk. You pay the premium to limit your risk and to gain leverage.

Buying calls allows you to participate in a stock or ETF while limiting your downside risk. You pay the premium to limit your risk and to gain leverage.