9

Amplifying Corporate Strategy

True Amplifiers increase the impact of organizations. Organizational impact is measured through the lens of value created for its stakeholders. Not all stakeholder value is created equally. One of the most important factors in creating corporate strategy is to fully understand the stakeholder value and time horizon of the strategy. Stakeholders include shareholders, employees, customers, and the societies in which they operate. Companies play a vital role in the economic engine that drive worldwide economies and raise the standard of living for all. The Business Roundtable recently adjusted its statement of purpose of a corporation to be more in line with the values of all stakeholders, not just shareholders.1 We believe effective corporate strategy takes a long-term view of the benefits for the stakeholders, and doing so creates an environment for companies to thrive well into the future.

The rate of change in the global economic environment continues to accelerate at breakneck speed. In this rapidly changing business climate, Amplifiers are playing an increasingly important role by constantly feeding data, insights, and other information into strategy formulation within their companies. It's impossible for leaders of large organizations to have a firm grasp on all of the market forces and details that affect strategy. Leaders cannot be successful without appropriately leveraging all the human resources at their disposal. Some leaders call this “returning authority,” when certain decisions are expected to be made closer to the front lines by followers who are closest to the fact pattern.

It's always been amazing to me to see how many different strategic frameworks have been published over the years. There are hundreds of books on strategy, most of which are pitching a particular strategic framework, method, or process for the company to follow. In our consulting business, we also have particular models that we deploy on a situational basis for different strategy engagements for our industry clients. Over the years, we found that what works best is to layer in different concepts from different models depending on the emphasis of the strategy. But regardless of the model used, the single common element of all good strategy projects is the human element and rigorous thought.

One of the fascinating elements of watching corporate strategy development unfold is how the organization experiences the “journey of the strategy.” For most people in the organization, when a leader articulates future strategy, it is as if they're standing on the South rim of the Grand Canyon unsure how to get to the North rim. The journey of the strategy is how the organization adjusts, adapts, learns, grows, and repositions the product or geographic portfolio, teams, and resources to get there. Frequently, these multiyear strategy efforts are launched with much fanfare. As the strategy unfolds over the ensuing time periods, fatigue starts to set in across the organization. Successful leaders need to understand this natural occurrence and nurture the organization along so that the proper pace can be maintained, enriched by leadership along the journey.

There are four key elements to effective corporate strategy. At every level, it is the human element that shapes the effectiveness of that strategy.

- The quality of the strategy itself. The creation and the quality of the strategy is an output of human analysis, research, scenario planning, visioning, and other activities to create the strategy. Amplifiers have a keen sense for the needs of all stakeholders and how to incorporate these needs into the strategic plan.

- The execution of the strategy. It doesn't matter how good the strategy is if the company cannot execute. A good strategy and a good execution of that strategy need to come together for an organization to be successful. At the heart of strategic execution are the people in the organization, not the strategy itself. An organization that develops a brilliant strategy that it can't execute will suboptimize stakeholder value.

- The sustainability of the strategy over time. Understanding the sustainability of a particular strategy is also critical. Some companies believe they are innovative, yet they pursue an acquisition strategy instead of creating an innovative culture. This works until the company is faced with massive goodwill and debt on the balance sheet.

- The agility of the strategy to accommodate strategic shifts. Great companies are able to pivot quickly and adjust to key market forces. They have built agility into their strategic processes. This is obviously far more difficult in heavily capital–intensive businesses with long product development cycles, but, nonetheless, strategic agility to capitalize on an emerging trend, or disengage a particular line of business, is a key element that separates great companies from good companies.

According to McKinsey & Company, 70 percent of transformation efforts fail.2 This is a striking statistic and leads us to ask several questions. How is success measured? Why do these transformation efforts fail? If so many transformation efforts fail, why do executives pursue them with the fervor that they do? Reviewing data from earnings calls and investor presentations reveals that almost all companies are pursuing a stated strategy. Does this mean that 70 percent of the Fortune 500 are pursuing a strategy destined for failure? Why do the 30 percent succeed? What do these 30 percent have in common? We believe the answer to this last question rests in how they activate Amplifiers to influence strategy formulation and execution.

Organizations measure success in a variety of ways. For many companies, they measure success by financial metrics such as market share, growth rates, or stock price performance. Other purpose-driven organizations measure patients served, life-saving therapeutics brought to market, or other societal benefits delivered to their constituents.

There is a vast array of strategic frameworks that exist. Some have been popularized over the years by major brand-name consulting firms. One example is the strategy of being number one, two, or three in an industry. This strategy was pursued by a number of former great companies. American Airlines flew itself into bankruptcy and was acquired by US Airways. Chrysler drove itself into the ground and was acquired. IBM rested on its laurels and failed to innovate. The transformation challenge at such a large conglomerate is significant. Nokia transformed itself over the course of a century, but after they ascended to the top of the smartphone market, seemingly achieving the stated strategy of being the top player in the market, they fell precipitously. Some of the biggest and well-funded number one, two, and three brewers of beer missed the craft brewing craze entirely. They were swept up in their own strategic echo chamber only to miss the trend. To be sure, these organizations had some great leaders at the helm, but despite spending tens of millions of dollars on strategy, they failed to recognize what was eroding their success. In some cases, they were able to recover and thrive, but in other cases they have fallen into obscurity.

Why does this highly touted business school strategic philosophy fail so frequently? And why do so many companies still pursue it? No doubt, scale is helpful, but it is not essential for long-term success. In fact, evidence shows that being number one, two, or three in a market is far from guaranteeing long-term success. What then separates those who maintain the top spots and continue to execute well over time? There is some evidence that hubris can exist at the corporate level as well as the individual level. When this mindset is fixed in the employees of the firm, it hampers the ability for true Amplifiers to emerge.

Another common strategy is an untethered pursuit of growth for growth's sake. These acquisitive companies bought other companies, leveraging their balance sheets along the way. The amassing of goodwill to fund growth can work only in environments of low interest rates and rising stock prices. This strategy does produce growth, and when executive compensation rewards growth, this strategy is expensive for long-term stockholders. There are endless examples of companies that grew through acquisition but could not produce organic growth. When an existential shock hits the market, these companies fall from grace quickly.

We saw this strategy unravel recently during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Many companies, especially those in retail, who borrowed significantly to acquire companies for growth, were unable to survive the revenue shock caused by store closures. Companies with a strong balance sheet were able to withstand the disruption brought about by widespread shutdowns. There were surprising stumbles by companies not immediately thought of as at-risk because of the shutdown.

If 70 percent of transformation efforts fail, why do leaders embark on them? There are several reasons why business leaders create new strategies or undertake a business transformation:

- New leader—new strategy. The shelf life for a non-founder CEO is about eight to twelve years. CEOs transition due to normal succession planning or lack of performance. In the latter case, if the business is broken or is underperforming, there likely is an urgent need to make strategic adjustments or even transform the business. However, when a new CEO is promoted, or especially if they are brought in from the outside, they typically like to roll out a new strategy. It's rare for a new CEO to continue to pursue the previous leader's strategy. What's interesting about this phenomenon is that the strategy is more a reflection of the individual at the top than the company itself. When viewed through this lens, this is the most precarious rationale for a new strategy and especially a transformation. It's understandable that a new leader wants to make a mark, but the risk is the attachment of the strategy to the leader and not the connection/association of the strategy to the organization and its mission or purpose.

- Product or market stagnation. There are a number of industries that have reached maturity and will not be around in the future. Some of these companies are able to foresee the trend and proactively adjust their strategy well in advance of the change. And many of these companies are able to make these pivots time and again. For instance, I remember as a kid growing up in the 1970s watching the gasoline lines stretching for blocks. Neighbors could only go to the pumps on certain days based on their license plate number. Back then, experts surmised that by the year 2000, there would be no more crude oil left to be extracted, and thus, there would be no more gasoline. In retrospect, there were a number of strategic miscalculations made and in fact, daily crude oil output in 2020 far surpassed that of the 1970s. This was enabled largely through new oilfield discoveries and new technology to extract oil from the earth that was not possible back then. This illustrates how big oil companies have been busy for decades adjusting their strategies to ensure their survival.

- Technology upheaval. The technology changes that affect some industries have been remarkable. One of the most famous cases of technology annihilation is how Netflix destroyed Blockbuster. Netflix clearly understood what it was setting out to do, but Blockbuster did not appreciate the strategic threat and could not bring itself to disrupt its own business model. Blockbuster failed to realize that it was becoming a corporate zombie. It's interesting to think about the tech-enabled disruptors today in the established or entrenched companies that they are trying to upend. In retrospect, it is easy to see how Netflix put Blockbuster out of business. But how many business leaders are running a Blockbuster equivalent in a different industry? At what point do business leaders recognize the threat or the trend?

The auto industry is a fascinating example of a combination of megatrends coming together. First of all, we will eventually deplete fossil fuels, and the industry as constituted depends on combustible engines. Therefore, all auto executives need to incorporate this fact into their strategic thinking. Second, the technological advances in power storage and batteries are making it possible for electric vehicles to take hold. To be sure, the infrastructure for battery-operated cars requires a substantial investment, which likely will be accomplished through some sort of public-private partnership. Again, leaders of traditional car companies who do not incorporate electric vehicles into their fleet strategy will not be successful long term. Third, the strategy of being number one, two, or three in the market is a lazy strategy. Tesla is not even in the top ten of auto manufacturers, yet it currently has the largest market capitalization, with its next closest competitor, Toyota, at a very distant second.3 Finally, the rise in popularity of special purpose acquisition companies has made it possible for a number of emerging electric vehicle manufacturers to tap the public equity markets, raising capital and their brand profile. Many of these emerging electric vehicle companies will end up failing or being merged into others. However, some of these companies have a market capitalization that exceeds traditional auto manufacturers and may use that inflated currency to buy a traditional player. The confluence of these strategic considerations in the auto industry will be fascinating to watch.

- Existential threat. The most obvious example of an existential threat was the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic had on many industries, including retail, travel, and entertainment. Many companies were already stretched on their balance sheets. When markets roll along incrementally, debt-burdened balance sheets do not play a critical role in corporate strategy. However, as we saw in these industries, many companies with stretched balance sheets ended up filing for bankruptcy, despite significant government intervention. Companies end up with stretched balance sheets for several reasons. For the most part, this happens as a result of heavily capital–intensive industries, leveraged buyouts, recapitalizations, or pursuing an acquisition strategy. Rarely does one see stretched balance sheets from working capital expansion due to profitable organic growth.

Companies in many industry sectors have been forced to make quick decisions to ensure their survival. The difference between companies that have thrived during the pandemic and those that have struggled extend beyond their balance sheets' ability to withstand the shock. Companies that have invested in digital tools and engaged consumers in a digital fashion have been able to weather the storm. For example, companies in the casual or quick-service restaurant industry that have had a digital strategy in place to enable mobile ordering and pick-up already in place, such as Starbucks, Chick-Fil-A, or Chipotle, experienced far less revenue impact than their competitors who didn't have mobile capability. Retailers who were able to quickly enable curbside pickup were able to soften the blow to their top-line revenue.

- Shareholder activism. Shareholder activism is a key driver for many corporate strategy initiatives. Activists advocate for change in many ways. They usually want companies to streamline their operations by divesting what they call non-core brands or divisions. In other cases, activists may advocate for combining assets or divisions with other companies in order to achieve scale. There have been some high-profile activist campaigns over the years. In some cases, the CEOs cater to the activists and address their strategy. On the flip side, there are CEOs like Indra Nooyi at PepsiCo, who have stood firm and have actually used activists to strengthen the resolve and the organizational commitment behind its strategy. Watching Nooyi in interviews defend her strategy at PepsiCo against the activists' attacks was a strong display of her leadership and conviction.

Necessary Ingredients for a Successful Transformation

Companies and their leaders learn from their failures and their successes. Through this lens, we try to learn why transformation projects and strategies fail. However, it is equally as important to understand why they succeed. In our experience working with companies to help them create and execute critical transformations, we identified at least seven key ingredients for success. We note, however, that understanding motives comes into play here as well. Companies and their CEOs have motives to embark on strategic initiatives. Assuming the motives are sound, the following components enable success.

- Soundness of strategy. The first component is the soundness of the strategy itself. There are a number of different methods to build a comprehensive and visionary strategy. It is critical to fully understand the organizational motives and strategic imperatives before embarking on a strategy effort. The methods per se are not as important as the robustness of thought, data, and insights used to formulate the strategy. Great leaders engage Amplifiers in strategy formulation. The strategy needs to incorporate physical, financial, and human assets and resources. Amplifiers will stretch the organization to achieve greater outcomes while shoring up areas of the business that need to be addressed. Clearly articulating the critical elements of the strategy, including the vision, goals, metrics, tactics, and road map, is essential for leaders to establish and communicate to the organization. The leader needs to create enthusiasm throughout the organization to increase the odds that they will actively participate in advancing the company toward its stated goal. This is one area where Amplifiers can play a vital role.

- Stakeholder alignment. Stakeholder alignment on a single vision is a necessary ingredient for success. Incorporating Amplifiers or Amplifier representatives from each of the key stakeholder groups ensures that stakeholder needs are either incorporated into or addressed in the strategy effort. It's generally impossible for all of the needs of all the stakeholders to be met. Therefore, there is a series of trade-offs, resource allocation, risk analysis, and other machinations required to arrive at the strategic vision. Given these trade-offs, the vision needs to be inclusive enough to paint the picture for those stakeholders who may not benefit as much. In this way, Amplifiers play a particularly important role as change agents. As influencers, they can persuade other followers to see the overall benefits of the trade-offs made so that the sum of the strategy and its benefits outweigh the trade-offs and their costs.

- Gap analysis. Unless the strategy is incremental, all transformation efforts require gap analyses that clearly define organizational shifts that are required to achieve the new vision. This gap analysis typically involves a comprehensive review of the current state of the business. For example, a biopharma company seeking to excel in oncology therapies might realize a gap it has in its R&D pipeline or depth of bench scientists able to discover new oncology drugs. Amplifiers help to increase the impact of gap analyses by critically assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the company to ground the vision in reality, while providing an achievable picture of the future.

- Funding the journey. Executives need to properly allocate financial and human resources to enable the success of the transformation journey. Leaders need to understand the long-term investments required to fully execute the strategy. This inevitably requires a set of trade-offs between short-term projects and, in some cases, conflicting change initiatives. As a result, there is a series of start-stop decisions as well as reallocation of human resources to properly staff the initiative. In the end, the funding needs to support the strategic journey.

- Change is communicated and role modeled. The case for change presented to the organization needs to be compelling and well communicated. Furthermore, the organization needs to see the leader role-model the behavior it expects to change. When Amplifiers are aligned with the leader, Amplifiers can help communicate and model this change to the broader organization.

- Accountable execution. Most corporate strategy projects involve a series of work streams. Each of these work streams needs to clearly fit together with visible goals, schedules, and allocated resources. Leaders need to be accountable to the organization to execute the strategy work streams, as well as to deliver the promised business benefits. Over the years, we have seen leaders roll out new strategies to be met with skeptical eyes among the rank-and-file employees as they view it as the “strategy du jour.” Being accountable along the way, leaders can deliver on elements of the strategy by setting the foundation, building credibility, and gaining momentum throughout the organization.

- Agile execution. Companies are shortening their strategic planning horizons and embracing a more agile strategy execution. Consumer trends, technology advancement, shrinking R&D discovery cycles, and other factors demand that companies rapidly adjust to changing market conditions, many times midstream. Companies who have an agile mindset are not caught up in their own agendas and can pivot more quickly to adjust and capitalize on new opportunities. That said, companies obviously need to understand the difference between short-term adjustments and the long-term strategic impacts of their transformation efforts.

At Clarkston we use an acronym to help the leaders with whom we work succeed in their transformation journeys. We have found that all the elements of EFFFORT need to be incorporated into the strategy or transformation initiative: Energy, Focus, Flexibility, Funding, Organizational (re)alignment, Resources, and Time.

Energy

As mentioned, many new strategies get created when a new CEO is put in charge or if there is a major existential jolt to the company. This seems to be the case whether or not the new CEO is appointed from the outside or promoted from within. Leaders typically want to make their mark on the company, and this is typically done through creating a changed vision for where they want to take the organization. The leadership team sets out with significant energy to frame this new vision, coupled with the drive to push it out throughout the employee base. However, it is amazing how often there is a disconnect between the energy at the top to advocate for change and the inertia present in the organization that is stalled.

In the best of times, a new CEO is appointed after a long, successful career of the predecessor. In this case, the organization is doing well, and the company's flywheel is rotating well without the need to exert much additional energy. This situation presents a challenge for the incoming leader. The organization is accustomed to the success it has generated over the previous years. New strategy and direction may be met with skepticism because the organization doesn't understand why it needs to change its successful methods or why a new vision for the future is even necessary. Here is where the phrase “the good is the enemy of the best” presents a particular challenge for the incoming leader. The new leader needs to channel the positive momentum the company has and frame the future opportunity in a way that will inspire and energize the company into action.

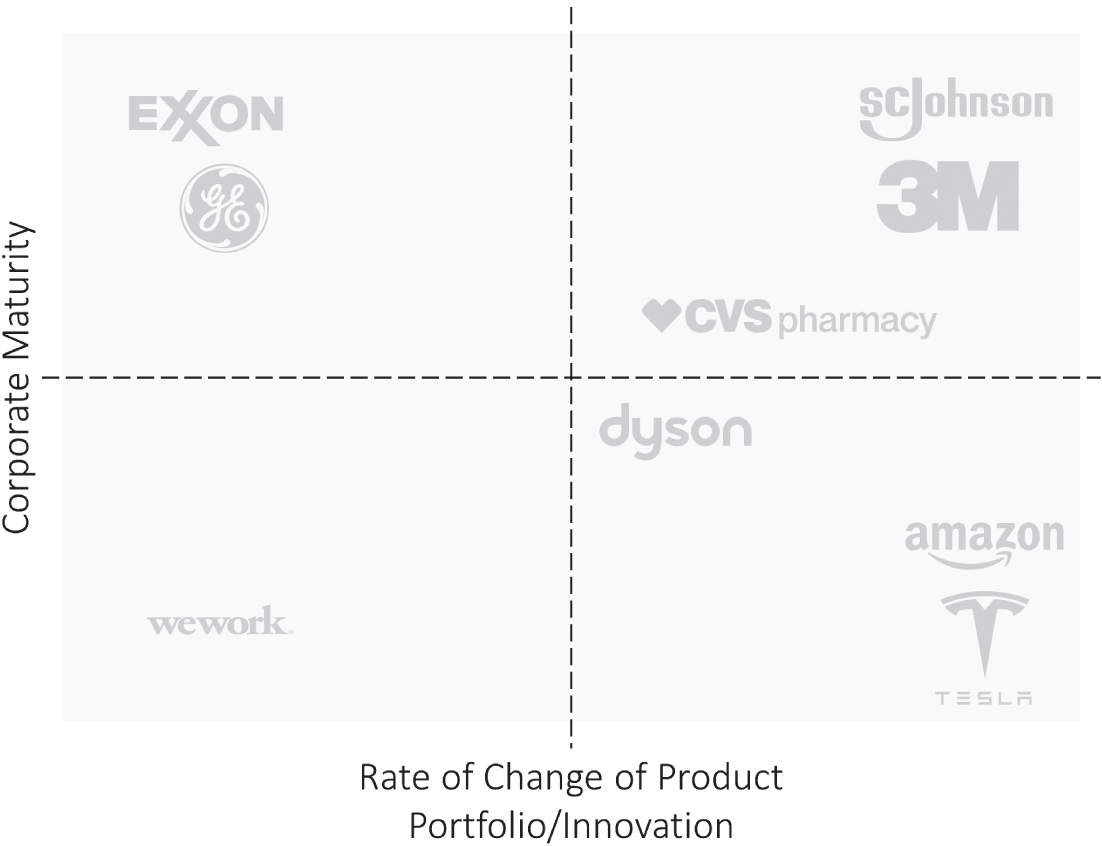

In other cases, the organization is stalled, and the new leader is tasked with changing the course to make new progress. In this case, the leader needs to break several habits throughout the company that are not producing the desired outcomes. Often, companies that are stalled have become complacent or incremental in their thinking and actions. Injecting energy into this environment is essential, albeit complicated. The most effective leaders will tap into Amplifier talent to magnify the impact and create positive energy for this change. In Figure 9.1 we show companies that have overcome the inertia quotient. These are companies that have been established for decades yet continue to innovate their products or how they do business.

Amplifiers create the energy necessary to drive a new strategy or transformation effort. The first activity is to tap into Amplifiers at all levels in the organization. Without the energy necessary to carry out the change, these projects will fall short of expectations, and thus fail. Amplifiers have a keen sense for the level of energy and effort needed to drive sustainable long-term change, to break bad habits, or to insert positive momentum in other areas.

FIGURE 9.1 Corporate Culture: Inertia Quotient

Flexibility Versus Focus

Any leader who has undertaken a large strategy project or transformation effort understands that rarely do these initiatives go as originally planned. Inevitably something will come up. The world we operate in is not linear. The best laid plans can be disrupted for myriad reasons—internally driven and externally driven. For larger companies, strategies are very complicated and must consider various scenarios, including those with lower probabilities of occurrence. Opportunistic M&A transactions present a common impetus for required adjustments to a strategy. Not all acquisition targets that would be good additions to the portfolio are available for sale at the optimal time. Acquisitive companies understand that when these assets hit the market, the company needs to be able to act quickly. On the flip side, when there is inbound interest for a portfolio asset, leadership also needs to be in a position to act quickly. Long-term portfolio planning needs to be focused and flexible.

Almost all companies are in various stages of executing a multiyear strategic plan. Virtually none of the executives within our client base were able to anticipate the impact the pandemic would have on their ongoing strategic initiatives. Every one of these clients needed to inject flexibility into their strategic plans. Some of our retail clients required wholesale change to adjust to store closures and significant decline in retail traffic. Other clients in our biopharmaceutical practice needed to adjust their focus in the lab to create vaccines and therapies necessary for public health. In other cases, our clients simply needed to make various course corrections to adjust for the virtual work of their white-collar team members while creating the process adjustments necessary to ensure the safety for their frontline blue-collar workforce.

Companies with the vision and foresight to shore up the balance sheet in advance of the pandemic were in a far better position to weather the storm. Many companies learned from the impact of the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, understanding that they were susceptible to market-driven shocks beyond their control. These companies took action to ensure that their balance sheets were strong so that they could be in a position to make thoughtful decisions without panicking. The pandemic tested the contingency planning element of strategic planning for many businesses. Many strategies are built based on robust market research and projections of demand and competitive positioning. However, downside planning is typically less of a focus. Many times, executives and visionary leaders are optimistic and don't dwell on negative scenarios. Here, Amplifiers are key in playing the devil's advocate role in a constructive and productive manner. The trusted skeptic Amplifier can pose the challenging and critical questions in an effort to shoot holes in the strategy in advance of the strategy deployment. If done well, this prepares the organization to adjust and be flexible when these outside existential shocks hit the market.

However, some organizations fail in part because their strategies lack focus and are too flexible. Although companies need to remain agile, successful companies stay focused on the long-term strategy and do not chase the short-term whims of the next shiny object placed in their path. This is a tricky balance, as we've seen some of the large and established consumer products giants miss major new consumer trends like craft beer or Greek yogurt. So, the balance between focus and flexibility is a fine line that needs to be actively managed.

Funding

One of the essential elements of any transformation effort is the proper allocation of human resources and funding. We are commonly engaged to help leaders create the transformation road map and journey. One of the key elements that drives success is the creation of clear goals and expected business outcomes that are properly funded with a demonstrable return on investment.

Companies make five mistakes when allocating resources for transformation efforts. The first is failing to properly allocate the adequate human resources, internally and externally, to staff the transformation. Another mistake is failing to account for the time necessary to change or influence behavior toward the new destination. This may be because of a lack of appreciation for the current state of the company. Or perhaps the leader has been in an echo chamber and fails to understand the inertia that exists throughout the company.

The third trap is tripping over dollars to pick up pennies. Some pursue quick wins that are worth pennies at the expense of more substantial harder-fought wins to pick up dollars and position the firm in a substantially better place for long-term success. In some turnaround situations, quick wins are necessary to create a stronger income statement or balance sheet necessary for the company to be more strategic in the long run. However, good companies seeking to be great ought to carefully consider the trade-off of pursuing near-certain short-term smaller gains that prevent longer-term and larger gains. Sometimes it is necessary, and more effective, to push for more impactful change, even knowing it may be a harder fight.

The fourth mistake is funding transformations off the company's balance sheet. Some companies justify new initiatives only that are capital projects, leveraged buyouts, changes to revenue recognition methods, or acquisitions that add to goodwill on the balance sheet. Although all of these can be pursued for legitimate reasons, we do see far too frequently how companies get derailed by leaning on these methods instead of building a compelling case with a strong underlying strategic rationale.

The fifth trap is focusing on short-term quarterly performance instead of adequately funding the strategy in the short run to achieve long-term success. There is a disconnect when public companies are taken private because they need to reinvest to transform the business. A notable example is Dell, which was a very successful public company for a period of years but ultimately failed to innovate and needed to transform. Dell was taken private, which enabled it to invest for the long term without the quarterly scrutiny imposed on it by institutional shareholders. I'm always impressed by the CEOs who have the courage to stand up to these institutional shareholders and impress on them that the decisions they are making today will benefit stakeholders years down the road.

Organizational (Re)alignment

Effective leaders understand that they need to have the right organizational structure and culture in order to be successful in carrying out any transformation effort. The right people and mindset are needed to drive change. We have seen time and time again unwillingness from executives to make the changes they know are right. Great leaders understand, as Jim Collins states in Good To Great, that having the right leaders on the bus is essential for long-term success. One of the common mistakes or regrets leaders confessed to me is that they waited too long to make a necessary change in key personnel. Rarely do they say that they made the change too quickly. Having the wrong people in key roles never gets better with time. In fact, having the wrong people in key roles has a negative impact on other followers and Amplifiers, and this erodes the credibility of the leader. Leaders are often loyal to these executives, but the rest of the organization already knows they should be swapped out.

Many companies are incremental thinkers and have an incremental culture. Often seen in large and established public entities, these companies evolve in this manner based on long periods of managing quarterly numbers, while individuals in the organization play the political game safe as they seek their next promotion. It is a cascading crescendo of micro-decisions and incremental moves that create a difficult culture for real change to take root. Most companies do not fully see that they are even in this category. They carry out their businesses quarter in and quarter out. We call them zombie companies because they are dead and don't seem to recognize it. Unless these companies get resuscitated, they will not perform better than overall GDP. Many of these companies can change course to become more innovative or entrepreneurial with the proper injection of a combination of long-term thinking, vision, acceptance of failure (experimental, new business model, and innovation failure), and organizational change. Discovering the Amplifiers and potential Amplifiers within these companies can mean the difference between breathing life and energy back into their innovative cores or seeing them wither and fade away into obsolescence.

Over the years, we have seen companies reorganize in an attempt to increase sales or change the culture. Although reorganization can play a role in such change, it cannot be the sole means to the end. It can only be part of the puzzle and not the complete answer. Companies with obsolete product portfolios cannot reorganize their way into success. Companies with static incremental culture cannot reorganize their way into creating a culture of innovation. Leaders pursue reorganizations simply because it is an obvious and public display of “change.” However, these leaders are confusing a reorganized corporate hierarchy with the underlying change in mindset that is actually needed for real change to take hold. Amplifiers enable organizational change and mindset change, thus unlocking the power of the masses needed to increase the probability the organization will achieve the strategic goals of the transformation effort. When included as part of a comprehensive strategy, organizational realignments can play a powerful tool for creating lasting change to support the strategy and cultural shifts.

Resources

Adequately resourcing strategic transformation projects is essential. Most companies have more to do than resources with which to do it. Leaders must evaluate the trade-offs and wisely choose between what they are going to do and what they are not going to do. Taking resources away from one area of the business to support another is a difficult decision for many executives to make. Great leaders demand the best people for their transformation efforts. This puts even more pressure on the department managers. Many times, the departments that need to free up resources for a transformation effort often complain that they are already understaffed as it is. But there is no gain without some level of pain. Amplifiers step in to help their colleagues understand the impact in the short run of their increased workload and help the leaders paint the picture for why the change is necessary to create a better long-term and sustainable company for all the stakeholders.

Transformation efforts fail or succeed largely as a result of the people who are assigned to carry out the transformation, but also by the people who need to embrace the work required of the transformed enterprise. Companies with a talent development mindset understand how they need to evaluate and activate Amplifiers to fill critical roles on transformation initiatives. Most large transformation projects require not only identifying outstanding internal resources but also high-quality external resources to support the initiatives. Unfortunately, the purchasing function often plays a more prominent role in selecting external talent than does the HR function. Instead, purchasing should play a supporting role to the HR function when selecting external talent. The HR function has the training and skills necessary to understand the full picture of human talent and culture, enabling the transformation project the best chance for success.

Time

Most transformation efforts worth their weight take time. Patience is a virtue, and effective leaders need to balance making progress with the fact that transformations are multiyear efforts. Organizations require institutional stamina to persevere through these multiyear transformation efforts. This is especially true when the culture needs to be changed, when the change requires long product development cycles, or when the required time to adopt to a particular change is longer than expected. Therefore, leaders need to set achievable interim milestones that have clear goals and expected outcomes. These multiyear transformation efforts are a bit like a relay race. Often, the leader who embarks on the journey and runs the first leg needs to hand the baton to the successor to continue to carry on the race. Amplifiers can help bridge that gap of institutional knowledge and fortitude.

Amplifier Impact on Corporate Strategy

True Amplifiers play a special role in helping companies realize their corporate strategies. Any leader who has undertaken a transformation or strategic initiative understands the crucial role true Amplifiers play. Amplifiers are motivated in a variety of ways to help inform, shape, develop, and execute corporate strategy. These individuals have a special ability to see the future, discern patterns, pick up trends, spot opportunities, and fundamentally see the existential needs to transform. Amplifiers also have a strong sense of responsibility to help the leader navigate the ship into new waters based on a compelling belief in the mission and the purpose of the company. In situations where there is a burning platform, they feel a particular obligation to help the leaders lead the transformation efforts and magnify their power throughout the organization.

Some Amplifiers are motivated by their own personal desires to advance their careers or even by the sense of adventure. Amplifiers are never satisfied with the status quo, and they have a strong sense that any company not advancing forward is actually falling behind. They are not afraid of change and in fact garner energy from change in the desire to constantly improve how they are operating as a company.

Successful companies use Amplifiers to serve as the upward feedback mechanism to advocate for change and bring fresh ideas into the strategic planning process. Given that Amplifiers exist throughout the rank-and-file employee base of the company, their ideas are closer to the action in the field and, if channeled correctly, can bring tremendous insight into the strategic planning process. Because most Amplifiers have a low self-orientation, they place a higher value on the company and its many stakeholders than they do on themselves. The pureness of their motives means the strategic inputs are often synthesized into recommendations that circle back up the corporate hierarchy.

Some leaders are gifted at anticipating the future but are unable to translate that vision into language and actions the organization can understand. The leader may suffer from “Cassondra's Curse”—the blessing of the power to see and predict the future, but the curse of being unable to paint a clear picture of it. Often, such leaders speak in “riddles” when describing the vision and are not fully able to cascade the transformational vision throughout the organization. Amplifiers play a crucial role in translating the vision to a believable course of action for the rest of the organization to follow. They bring a unique blend of closeness to where the rest of the company stands today and an understanding and appreciation of the leader's vision for the future.

In other cases, leaders and their executive teams get excited about a particular idea or strategy. To achieve these goals, these leaders need to be involved in more than just the ideation and the vision but also to oversee the execution. Frequently, and given the demands on their time, some leaders will kick-start the strategy or transformation effort and then get distracted or pulled into other seemingly more pressing or urgent matters. Effective leaders need to balance these inevitable conflicts by strategically delegating when appropriate while publicly supporting the initiative through to completion. Amplifiers can play an important role in enabling the leader not to fall into the trap of believing the “innovator must be the implementer.” Amplifiers enable leaders to be part of the execution in a visible way while still maintaining focus on other aspects of the business.

One of the key challenges in executing corporate strategy and especially transformation initiatives is the dual engine dilemma, which suggests that the organization must operate dual engines—the current business and the newly conceived transformed business. In many cases, the new engine cannibalizes the bread-and-butter existing business. In other cases, the new engine requires implementing a business model that contradicts the company's legacy success. Nurturing the new engine while keeping the lights on in the existing engine is not an easy task. Occasionally, inertia will drive energy toward the existing engine, and the organization may consider the new engine a distraction. Here's when Amplifiers can play a critical role in helping the organization power through the dual engine dilemma. They can help leaders communicate the need to reallocate resources toward the new lines of business that do not seem to advance the company's legacy economic engine. In some cases it may be an obvious extension to the product line, and in other cases it may be a revolutionary new model for bringing value to customers. In both cases, Amplifiers are able to articulate the benefits of the new strategy in a way that influences others to join the effort.

Take the auto industry as a classic example of the dual engine dilemma. All of the top ten auto manufacturers are facing the same fundamental strategic considerations. The pace and approach that each considers will be the difference between winners and losers. What will separate the strategies these auto manufacturers will deploy over the next decade will depend largely on their corporate culture and the degree to which they have Amplifiers throughout the organization driving change.

In the case of Volkswagen, we saw how a corrosive corporate culture can destroy consumer confidence and lead to widespread deceit. The top-down nature of their command-and-control hierarchy, coupled with sheep-like followers, yielded poor performance and ineffective strategic decision-making. The issue facing the automakers has been obvious since the oil crisis of the 1970s. Emerging battery technology and the strong consumer desire to eliminate greenhouse gases are market forces now at play that were not as prominent decades ago, when the auto manufacturers were facing the same dual engine dilemma. Until Tesla entered the market, there was no real competitive threat to cause the organizations to move away from their primary economic engine. Great companies, such as Apple, Google, 3M, Amazon, and others, leverage Amplifiers within to spot and act on innovative new opportunities to change their economic engines ahead of it becoming a crisis situation.

There are always more exciting ideas than organizations have the time or resources to pursue. Great companies and their leaders need to make these strategic trade-offs. Trade-off indecisiveness is a crippling handicap for companies and titled executives. Organizations must have a way to effectively and efficiently decide what they will do, what they will not do, and what they will stop doing. Amplifiers are able to magnify the strengths and weaknesses of the strategic choices confronting leaders and help them arrive at the best possible decisions. When organizations add new strategic initiatives and do not make the proper trade-off regarding what they are no longer going to do, the organization feels overburdened. Amplifiers can magnify the voice of the broader employee base so that leaders can appropriately disengage with certain nonstrategic initiatives or initiatives that may conflict with the ability to deliver on the transformation goals.

Nelson Mandela said, “When conditions change, you must change your strategy and your mind. That's not indecisiveness, that's pragmatism.”4 It is important to remain flexible while engaged in a transformation journey, which is long and hard and is never a straight line. The leaders and Amplifiers supporting and enabling the effort must often check progress against success measures, adjusting the course as necessary. They may need to scrap ideas that are no longer relevant or double down when new ideas emerge that are primed for magnified success. It is essential to adjust as conditions change while maintaining focus on the overall transformation journey.

When new CEOs are brought in from the outside, there is a natural period of time necessary for them to earn the trust of the organization. In other cases, as was the case of GE under Immelt, the CEO or titled executive has a high degree of self-orientation and the broader employee base is unsure whether the executive is out for himself or knows what's in the best interest of all the stakeholders. When there is lack of trust, dysfunctional and passive aggressive behaviors permeate the organization. Amplifiers play a critical role in building the trust bridge between executives and the broader employee base when needed. When trust exists, the organization will go to great lengths to help execute the strategy. Companies that operate with a high degree of mutual trust are able to form high-performing cross-functional teams that work together to deliver a common goal. During the inevitable peaks and valleys of the difficult transformation journey, this highly functioning team will be able to deliver a clear vision and strategy, magnified by trust and respect for one another. These high-performing teams remain aligned and focused on the priorities and goals at hand and are especially effective when leveraging the power of three Amplifier concept from chapter 3.

Most transformation efforts will encounter an unforeseen problem or mistake along the way. The best leaders will immediately step up and own the mistake. By publicly praising the individual who pointed out the mistake, the leader helps create a culture in which employees feel comfortable bringing forth shortcomings or defects that can be addressed early on in order to avoid disastrous long-term consequences. It takes a degree of humility for a leader to own the mistake and praise the person who brought it forward. Amplifiers hold their leaders accountable and keep them honest with this practice. They demand excellence and will constantly raise the bar for performance regardless of whether it is the leader or another colleague within the company.

Meaningful corporate strategies designed to create transformative business results inevitably create varying degrees of friction. Great companies and leaders embrace friction where it counts. Transformation requires the elimination of strongly held business models and paradigms and forces individuals to stretch or abolish the preconceived notions about the business and its goals. A lack of friction and transformation often means that the business isn't actually changing; it's repositioning or shifting but not actively transforming. Embracing the friction ultimately drives a better outcome for the business as a whole. By removing the conflict powered by egoism or fear, the remaining friction empowers business transformation.

Friction forces leaders to reexamine positions, test boundaries, challenge the strategic beliefs. These are all elements of a genuine transformation. As long as leaders are aligned to the ultimate goal and are committed to change, friction serves as a positive means to the goal. Amplifiers bring out creative friction among the key stakeholders to ensure diversity of thought, and differing perspectives are brought to bear not only in the formation of the new strategy, but also in its execution.

Notes

- 1. “Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘An Economy That Serves All Americans,'” Business Roundtable, August 19, 2019, www.businessroundtable.org/business-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans.

- 2. Harry Robinson, “Why Do Most Transformations Fail? A Conversation with Harry Robinson,” McKinsey, July 10, 2019, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/transformation/our-insights/why-do-most-transformations-fail-a-conversation-with-harry-robinson.

- 3. S&P Capital IQ, Clarkston research.

- 4. Nelson Mandela and Richard Stengel, Mandela's Way: Lessons for an Uncertain Age (New York: Broadway Books, 2010), 113.