Chapter 5

The Great Enabler

Mike Beuscher is the grim reaper of Orange County, California. He’s a tall, pleasant-looking middle-aged fellow who makes his living clearing out homes after they have been foreclosed on, shattering the dreams of those who reached for a better life, even if they knew it couldn’t last. For Mike Beuscher, business has never been better.

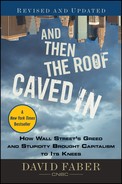

On the day we spent together, Beuscher gave me a tour of ground zero for the nation’s housing bubble: Orange County, California.We saw $750,000 homes now covered in graffiti inside and out. We saw gardens, once filled with flowers, now dried up and empty. We saw cockroach infestations, garbage piled high, swimming pools half filled with strangely green water. We saw houses denuded of all their plumbing, all their wiring, and all their appliances. We saw rat-infested homes that must have slept 20 people. We saw the grimy, unsavory, sordid underbelly of the housing boom, where anyone could get a mortgage to buy virtually anything when they could afford nothing.

Mike Beuscher’s license plate reads EVICTEM. It’s nice to see a man who embraces his work. And when his black pickup pulls up in front of a house, the message is clear: It’s time to go.

The homes that Mike Beuscher is sent to empty out and ready for sale are the homes in which people have stopped paying back their mortgages. Once homeowners miss three monthly payments they are considered in default on their mortgage. Foreclosure used to come soon after. These days, however, given the torrent of mortgage defaults, foreclosure usually doesn’t come for many months. But when it does, Mike Beuscher is there. Sometimes the people who live in these homes have been there for years, but more often than not, the homeowners Mike Beuscher is there to evict have barely been there long enough to memorize the address.

Mike Beuscher

Photo courtesy of CNBC.

Surveying the Wreckage of a Housing Bust with Mike Beuscher in Orange County, California

Photo courtesy of CNBC.

Mike Beuscher Shows Me a Future Breeding Ground for Mosquitoes

Photo courtesy of CNBC.

Mike Beuscher’s License Plate

Photo courtesy of CNBC.

They seized a brief opportunity to own a piece of the American Dream and now they’ve been scattered, their empty and decaying homes left behind as a reminder of that dream gone bad.

These are the people who received mortgages from all those lenders who were happy to grant them without regard to income, debts, or ability to put money down.

Why would financial institutions extend mortgages to people who could not pay them back? That does not make sense.

If those financial institutions that lent the money actually had to be concerned about whether it would be repaid, they would no doubt have invested a bit more time and effort in making certain their borrowers had a good chance of doing just that. But subprime lenders such as New Century and Ameriquest and Quick Loan were not concerned about being paid back. They parted with that mortgage as soon as the ink on the application was dry, selling it a few moments after the buyer of the house received their money. And who was buying these pitiful mortgages from their originators? Who would want to own hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of mortgages reflective of a huge decline in lending standards when everyone one of them was at risk should housing prices even so much as level off?

Before we answer that question, we need to make a necessary detour back to that time and place when Americans who wanted a mortgage had to unburden themselves of every last bit of financial information they could spare in order to get one.The bank that gave them that mortgage would often keep the mortgage on its balance sheet as an asset. That’s why lenders cared so much about whether they could repay that mortgage.

It wasn’t the most efficient of financial dealings. The bank that granted your mortgage had only so much money to allocate to lending. And while that amount might go up if its deposit base increased, the bank would never be in a position to give a mortgage to every potential homeowner who could afford one. It simply did not have enough money.That is why Fannie Mae was founded.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Hit the Scene

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Congress created Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) and gave it a mandate to buy mortgages from lenders, thereby freeing up capital for those lenders that they could use to extend more mortgages. Fannie Mae started as a rather modest effort. Its initial seed money of a billion dollars in capital was not going to let it buy up many mortgages. But because it was a government entity, it would in time be able to sell bonds to investors in order to raise more capital that it could then use to buy more mortgages. The bonds were an easy sell because people were sure they would be paid back since Fannie Mae was a government entity. Even after Fannie Mae went public in 1968, its status as a government-sponsored entity (GSE) allowed it to raise capital cheaply.

By 1982, Fannie Mae was funding one out of every seven mortgages made in the United States. And by then it had company. Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation) was launched in 1970, and, whereas its mission was identical to Fannie’s, it operated its business a bit differently. Well into the 1980s, Fannie Mae retained most of the mortgages it bought. I know that first hand. In one of the lowest moments of my professional life, in October 1986 (I remember the date because the Mets were playing the Astros in the National League Championship Series), I spent three days at Fannie’s northern Virginia headquarters pulling the mortgage-origination sheets of various borrowers (I was never told why). This, of course, was prior to the widespread use of computers and was one of a series of mind-numbing temporary jobs I held before thankfully embarking on a career in financial journalism.

Freddie Mac, unlike Fannie Mae, did not hold most of the mortgages it bought from lenders. It would bundle them together in what was initially called a mortgage participation certificate and eventually became known as a mortgage-backed security (MBS). The security, a pool of mortgages from across the country, paid its holders interest from the mortgage payments that were being made by homeowners (see Figure 5.1). It was normally rated triple-A (the highest credit rating) because American homeowners had a very good history of paying back their mortgages. Freddie Mac and eventually Fannie Mae (it offered its first mortgage-backed security in 1981 and would surpass Freddie in MBS issuance by 1992) would stand behind their mortgage-backed securities by agreeing to take back any mortgages in the pool that went bad. Of course, they received a nice fee for this guarantor service.

Figure 5.1 Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac would come to dominate the process for giving people mortgages in the United States even though neither company ever originated any of those mortgages. They did this by dictating to lenders the specific characteristics of the mortgages they would buy. If Fannie and Freddie told lenders they would only buy 30-year fixed-rate mortgages up to $250,000 with a loan-to-value of 80 percent from borrowers whose income had been well documented and who had FICO scores of over 700, then that is exactly what the majority of lending institutions in the United States would go out and originate. Fannie and Freddie set the standards under which they would purchase a mortgage and most financial institutions then conformed to those standards.That is how we got the term conforming mortgage.

Bill Dallas, who founded two mortgage lenders during his 30-year career in the mortgage business, watched Fannie and Freddie’s rise to preeminence. “Lenders on their own are not strong enough to put mortgage-backed securities together and then issue them directly to investors,” explains Dallas. “Most investors want a triple-A security and, long story short, the American business model for issuing mortgage-backed securities was Fannie and Freddie. Everyone knew they would stand behind the mortgages and their guidelines for underwriting mortgages had a history of working.”

It wasn’t the greatest business for the banks. There wasn’t much money to be made in granting mortgages that would conform to Freddie and Fannie’s standards, but for the decades of the eighties and nineties, that’s just the way it was, a commodity business.

Yes, there were always exceptions. Mortgages above Fannie and Freddie’s limit (which was $252,000 in 2002 and moved up to $333,000 by 2004) are known as jumbo mortgages and couldn’t be sold to them, nor could the mortgages being originated by the first wave of subprime lenders in the early 1990s. But jumbo or subprime mortgages at that time were a tiny part of the business, which was centered for decades on originating mortgages that could be sold to Fannie and Freddie.

Fannie and Freddie Get a Timeout

Unlike the banks they were buying mortgages from, the mortgage business for Fannie and Freddie was a money train. As the amount of mortgages they bought reached into the trillions of dollars, the two public companies became among the most profitable corporations in the world. They were lauded by investors for their exceptional earnings growth and for the predictability of their performance. Investors flock to companies that show consistent patterns of growth in earnings, rather than volatility in earnings, which can send a stock price down one quarter and up the next. Maintaining that consistency in order to keep shareholders happy, while their businesses became ever more complex, was not an easy task. Eventually, in order to preserve that predictability, the companies would have to lie.

In November 2003, after an 11-month review of its accounting, Freddie Mac divulged that it had understated its earnings by $5 billion over the past three years. In an effort to make its business look predictable, Freddie’s management had gone so far as to say it earned less money than it really did.The bulk of the accounting misstatement centered on Freddie’s attempt to hedge its exposure to changes in interest rates by using derivatives. The admission by Freddie immediately turned regulators’ attention to Fannie, and a similar accounting probe concluded 10 months later that it, too, had been guilty of manipulating its quarterly earnings so they would appear less volatile than they actually were. In Fannie’s case, most of the shenanigans were to overstate profits, but the effect was the same. “Fannie Mae management intentionally smoothed out gyrations in its earnings to show investors it was a low risk company. It maintained a corporate culture that emphasized stable earnings at the expense of accurate financial disclosures,” said a September 2004 report from Fannie and Freddie’s chief regulator, the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight (OFHEO).

With their credibility in tatters, Congress up in arms, and their regulator, OFHEO, on the warpath, Fannie and Freddie retreated from the market they had dominated for the past 20 years. They began to buy fewer mortgages in a period where people were buying and refinancing more homes than ever before. “Knowing our industry, at its heart it’s a people industry,” explains Bill Dallas. “It’s customer relationships at the front end and it’s being driven by small and medium-sized mortgage bankers that deal with Fannie and Freddie on the back end. We were used to being led by two big actuaries, this oligopoly that owned the world. So we got all of our rules from those guys and that’s what we did.”

Suddenly, the leader of the U.S. mortgage market had gone home. And with no one to tell them what to do, the mortgage originators found themselves free to expand the guidelines they had lived with for years as long as they could find a buyer for the mortgages they were underwriting. That’s when they met Wall Street. It was a union that would change the course of financial history.

Bill Dallas had dealt with Wall Street for much of his career. The lenders he had founded, First Franklin and Ownit, relied on Wall Street to buy their mortgages because most of them did not conform to Fannie and Freddie’s guidelines. Dallas had been selling mortgages to Wall Street for quite some time, but now, with Fannie and Freddie on the sidelines, the floodgates had opened:

The moment the mortgage originator met an unregulated Wall Street, those are two wires you don’t want to cross. Because the mortgage broker is there to help the consumer get the house, buy the property. They’re not naturally going to be saying “Oh, you know, I don’t want to do this.”

In 2003, roughly $4 trillion worth of mortgages were originated in the United States. It is the single largest amount of mortgages ever originated in U.S. history. In that same record year, 70 percent of those mortgages were sold to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Seventy percent of that $4 trillion in mortgages conformed to Fannie and Freddie’s guidelines.

In 2006, roughly $3 trillion worth of mortgages were originated in the United States. In that year, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac accounted for only 30 percent of the secondary market. In three years, the share of mortgages they bought had gone from 70 percent of all the mortgages originated to 30 percent. The guidelines for lending that Fannie and Freddie had so diligently applied to the mortgage market were no longer operative. So who stepped in to fill the void and buy all those mortgages made during a period of declining lending standards? It was Wall Street.

Wall Street’s investment banks had always played in the nation’s mortgage market. It was Wall Street that funded the first subprime lenders by buying their mortgages and packaging them into mortgage-backed securities that were then sold to investors. Of course, those MBSs carried a much higher interest rate and a lower credit rating than anything sold by Fannie and Freddie because they carried a higher chance of default. Wall Street also bought the prime mortgages that were too big for Fannie and Freddie and also securitized and sold them. Wall Street played in the mortgage market, but had always played outside the conforming space that Freddie and Fannie dominated and it was always a relatively small space to play in.

Without Wall Street to buy their mortgages, firms like New Century, Ameriquest, and Quick Loan could never have existed. That’s why they were known as capital markets lenders. They needed access to the capital markets, where bonds and stocks are sold, in order to have their mortgages packed into mortgage-backed securities and sold to investors. They got that access through Wall Street. But prior to 2004 their business, falling as it did in the “nonconforming” space, was still a small one.

Wall Street Takes Over

Myths have a way of being perpetuated long enough that they become unquestioned facts. One such myth that has been bruited about in 2008 and 2009 is that the lax lending standards of Fannie and Freddie promulgated the current crisis. It is not true. Wall Street rushed into the vacuum created by the absence of Fannie and Freddie in 2003-2005. It was Wall Street that took their market share and became the leader. It was Wall Street that encouraged mortgage originators of every kind to lower their standards by providing an endless supply of new capital to fund their mortgages. It was Wall Street that found willing buyers for U.S. mortgages around the globe in order to keep funding the mortgage market. It was Wall Street.

Michael Francis is one of those decent, hardworking guys who go to Wall Street, not because they think they’re going to be a master of the universe, but because it’s always proved a good place to support a family. Francis spent many of his 23 years in the mortgage business selling loans to Wall Street.Then he moved from the selling of mortgages to the buying of them, joining an investment bank in its capital markets division.Things went well for Francis. He would eventually run the capital markets side of the mortgage-origination business at a very well-known investment bank. He has asked me not to name it. While it is one of the best known of investment banks and it did participate fully in the mortgage business, it acted with a bit more sagacity than many of its competitors.

Michael Francis

Photo courtesy of CNBC.

Interview with Michael Francis

Photo courtesy of CNBC.

Francis explains his duties:

I was in charge of our sales force. . . . It’s really a buying force, but they’re called salespeople. Their job was to go to smaller, mid-size as well as larger mortgage originators, banks as well as privately owned firms, and show them what programs we had, what our rates and what our prices were and get them to sell more loans to us.

Francis’s job was to convince the people who ran mortgage-lending operations that they would do well to sell their mortgages to his firm. And how did he do that?

The first part of our pitch is that we are Wall Street. We’re the big bad guy that has all the access to capital that you need. That was the kind of lead-in, very typical of the way a lot of conversations started with people. And then once we get past the handshakes and everything we really just try to do a good job of explaining what the differences are around our program versus our competitors’. We’re going to give you a great price and a great rate and it’s all going to be quick.

An investment bank’s “mortgage program” comprises all the terms under which that institution will buy mortgages from an originator. It tells the originator what types of mortgages will be purchased and sets the credit standards that must apply to those mortgages. It tells them what the spread will be for those mortgages. A spread is the difference between what it cost the lender to originate the mortgage and what they are able to sell it for. Francis would also inform the lender of how quickly they would be paid by the investment bank.

Quickness of payment was an important point for many mortgage originators, who relied on a “warehouse” line of credit from a commercial or investment bank that gave them the short-term financing they needed to fund the mortgages they were making. The average mortgage bank that Francis’s firm dealt with had a net worth of between three and five million dollars. It could borrow as much as 20 times that net worth on its warehouse line of credit. “But if they’re a mortgage shop doing two or three hundred million a month, you can see they’re going to produce more loans than they actually have capacity for. So the goal for them is to get the loan closed and have us, the end investor, buy that loan as quickly as possible to allow them to relieve the warehouse line so they had money in the tank to lend to the next guy,” explains Francis.

If speed was of the essence, so was listening:

The places that I worked did a pretty good job of reaching out to clients and asking for opinions on how we could shape our business to make it easier for them. Mortgage originators are on the ground beating the pavement, trying to get loans to make money.They are naturally gonna come up with a lot of different ideas on how they could generate more revenue through more loan volume. So we would reach out to those folks to help us try and twist and turn our programs to give them a program they could drive a ton more volume through.

Remember Bill Dallas’s warning about “two wires you don’t want to cross”? This is exactly what he was talking about. Michael Francis’s firm and virtually every other Wall Street firm was not telling the originators what type of mortgage they would buy as Fannie and Freddie had always done. Instead, Wall Street firms were giving the originators free reign to tell them what mortgages they should be buying. And that’s exactly what happened.

After Fannie and Freddie pulled back from the market, investors who bought mortgage-backed securities were left to look to Wall Street to quench their thirst for this fixed-income product. “It was an absolute shift,” says Francis. “With so much liquidity moving away from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac the world just completely shifted and there were more Wall Street private securitizations being done than Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac MBS.” That shift gave Wall Street great power in dictating what mortgages would be originated and gave it pricing power versus Freddie and Fannie that it had never had. “We made it easier for a borrower to get a loan and then the cost of that loan on our side became much less. But for us, you wouldn’t have to give as much documentation. If the cost is the same, but you have to do less work, why wouldn’t you go left versus going right?” explains Francis.

Wall Street’s rising prominence was good news for Quick Loan Funding. “The way Wall Street works is if you have a need for a product, and you have a track record and you have volume showing that you can originate loans, then Wall Street will bend over backward to come out with a product to buy,” says Lou Pacific, a 30-year veteran of the mortgage business who was a vice president at Quick Loan.

Just as Mike Francis said, the originators were going to Wall Street and asking them for the money to back a certain mortgage product. Lou Pacific recounts how the conversations would go:

We’d approach Wall Street and say “Look, we have a product we think we can sell. And I can promise you $500 million a month or whatever in this product.” And Wall Street would say, “Okay, this firm has a track record, they want this product, they’re doing a lot of volume, let’s give it to them.” And let’s say it was Merrill Lynch or Credit Suisse or whoever it was they went to, the word on the Street would spread that this product could be funded by Wall Street.

When the word got out, as it always did, that Merrill or another firm was funding a 95 percent loan-to-value mortgage for borrowers with a 580 FICO and above, the other subprime lenders would quickly try to horn in on the action. The result: A whole lot of mortgages would get signed up for people who fit the parameters of that particular program because the mortgage companies were being incentivized to sell that loan, knowing they had a willing buyer. “The incentive was that you would get a larger rebate on the loan. If a broker did a loan, the lender [Wall Street] would pay a certain amount of money for that loan,” explains Pacific. “You would charge the borrower one or two percent of the loan as an origination fee and the lender would pay you up to three percent of the loan amount after the loan closed. It’s called a rebate or yield spread premium and that’s how you made your money.” Pacific says the key to attracting Wall Street’s largesse was having a track record, delivering volume, and putting people in mortgages at the highest rate possible.

Yes, that’s right: The higher the rate on the mortgage, the more money the originator would be paid in that rebate by Wall Street. “If you could sell the loan for a higher rate and sell a lot of them at a higher rate, then Wall Street was in love with you. They would bend over backwards for you. They would buy anything you’d give ’em, just about,” gushed Pacific. Subprime loans carried a low initial rate, but over the life of the loan a very high rate. It proved the perfect product for Wall Street. It also proved tempting for many of the subprime firms to convince consumers to take a subprime loan even if they qualified for a much lower-priced prime loan. “We used to get an awful lot of them [prime borrowers],” says Pacific unapologetically. “They were more concerned with the speed of getting a loan. And plus the average person doesn’t understand where their credit ranking is, some don’t think they can qualify for a good loan, but they can. So they’ll call and if you sell a loan with a higher FICO score, you’re going to make more money on it.” Pacific claims that when he encountered such a person he would refuse his business and tell him to go to his local bank.

Pacific says that during his time at Quick Loan, he never saw Wall Street reject a mortgage booked by the firm. “Once you have volume, the word in this small community here in Irvine gets out. And Wall Street goes strictly by volume and how much money they can make off the loans. So if you have a company that’s doing a lot of business at a high interest rate, which most of the subprime loans were, then they can make money on their end.” There was one caveat: The person whose mortgage was sold to Wall Street had to make the first three monthly payments; otherwise the firm that bought the mortgage had the right to give it back to originators like Quick Loan. After three months, the originator was in the clear.

A Tsunami of Mortgages

At the investment bank where Michael Francis worked, business had never been better. The firm needed to buy $100 million worth of mortgages each month if it had any hope of breaking even, and when Francis was putting things together in 1997 and 1998 that was just a dream. By 2002, $100 million in mortgage volume became a reality, and that was before Fannie and Freddie’s decision to retreat from the market.

“Within a six-month period of passing $100 million we were doin’ $500 million and at this point we’ve gone beyond our wildest expectations,” recalls Francis.

And it’s not just something that’s putting out a little bit of money. It was putting out a fairly substantial amount of cash. And it was a dominant fixed income asset within the firm. If there were no mortgages, fixed income would be a blip on the radar of the earnings of the firm. Now mortgages were the reason fixed income became as big as it was.

The world was flush with cash and mortgage-backed securities were more popular than ever. China and other Asian countries were watching their economies soar and were wracking up huge surpluses of dollars in the process. Meanwhile, Russia and countries in the Middle East that relied on the export of oil to the United States were swimming in dollars they needed to invest. The result was unprecedented worldwide demand for dollar-denominated products like the American mortgage-backed security. And if a firm could provide that much-in-demand investment vehicle, it could try to cater to all the fixed-income needs of its clients. “Not only would we get them a mortgage bond.We had convertible bonds. We had corporate bonds. There was debt to be structured. Now we could capture every investor and bring them everything they could ever want. And why would they need to go across the street when they could get it all from us,” explains Francis.

The bankers at Francis’s firm had never been busier.They aggregated billions of dollars in mortgages that had been originated all over the United States, separated them into different buckets depending on the type of loan (fixed rate or adjustable), and went about creating the pools of collateral from which the mortgage-backed security bonds would spring forth. “We would start to evaluate what type of bonds were being produced by other Street firms and what type of bonds some of our clients were looking for and then create pools of collateral to meet their investment needs.”

In fact, for many Wall Street firms it wasn’t enough merely to be able to package mortgage-backed securities. They wanted in on the whole process, from origination to packaging to selling and even to the exacting business of collecting people’s mortgage payments and distributing them to MBS holders (known as servicing).

Lehman Brothers was the first Wall Street firm to really embrace all aspects of the mortgage business. Bill Dallas remembers:

What was the Lehman model? “We wanna originate it. So we’re gonna buy originators and we’re gonna buy a servicer.” And they were pretty successful at it. They bought BNC Mortgage. They bought Finance America. They bought their own servicer, called Aurora. Well, Wall Street firms are pretty much lemmings. If Lehman’s doing it and they’re successful at it, then Bear Stearns will go and Merrill will go and Goldman will go. They’ll all go at it. And they all did.

And so they all were ready when Fannie and Freddie skipped off into their accounting scandal-induced timeout.The competition became fierce as Wall Street firms tried to land as many mortgages as they could lay their hands on, feverishly chasing the fees from creating the mortgage-backed securities that were now loved by investors around the globe. Lending standards quickly fell victim to the onslaught. Michael Francis remembers the slide in standards that led to the widespread use of mortgages that required no documentation of income.

“We started to loosen the guidelines,” explains Francis, “at the same time that more and more people were wanting to get in on that loan. And was it the absolute best loan for every single borrower? I would say, generally speaking, no. But the path of least resistance is the biggest reason that loan became very popular.” That and the knowledge that if one firm chose not to buy those mortgages, another surely would.

In 2003, Francis moved from one Wall Street firm to another. His new firm was a bit more cautious than the firm he had left and approached the stated income loans nervously. “We would have conversations about whether this was appropriate or not. For a very long time, everyone on our trading desk, and I think it’s safe to say everyone, felt that on a stated income loan it was appropriate to make the borrower think twice about what they were putting on that application.”

IRS form 4506 allows a mortgage lender to have access to a couple of key lines of a person’s tax return in order to verify his or her income. Francis’s firm tried to get lenders to have their clients sign that form. “We tried to implement it and we couldn’t because it literally would have shut production down to zero, because none of our competitors, Wall Street, or not, were asking for that form.” It’s the same story as the one told by Bill Dallas. If the lender making the mortgage or the Wall Street firm buying it had demanded accountability, they would not have been better off as a result; they would have been out of the business.

Once Wall Street allowed mortgage lenders to not even try to keep their customers honest, there wasn’t much left to do when it came to due diligence. There were automated tools that allowed the investment banks to ascertain whether the values ascribed to a particular property made sense given where the property was located. And the Wall Street firms could also verify that the borrower was a real person and the house they were buying or refinancing was in fact a house. But that’s about it. Everything else was taken on faith. And most of that faith centered on housing prices. If the asset class kept appreciating, all would be well.

Business kept on building. In 2002, Michael Francis was ecstatic to see his firm pass the $100 million mark in the amount of mortgages it bought in a given month. By 2005, his firm was buying an average of $4 billion a month in mortgages. That’s right: a 40-fold increase in monthly mortgage volume. And almost all of those mortgages were of the type sold by the guys in Irvine, California:They didn’t come close to conforming to the long-held standards once enforced by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

From Ownit to Out of It

The brief life of the mortgage lender Ownit, which was started by Bill Dallas in late 2003 and closed by him three years later, is instructive of the era. When Dallas founded Ownit, he wasn’t looking to capitalize on the housing boom, but rather a coming housing bust. “The strategy was that the brutal facts are going to affect the industry, and we’ll swoop in ’cause we have superior knowledge and better products. We were forecasting home price depreciation.” But Dallas wasn’t forecasting that Wall Street would take over the securitization market for mortgage-backed securities and in so doing extend the life of a small housing bubble while inflating it to enormous proportions.

Ownit’s main focus was on giving mortgages to people who couldn’t afford a down payment, but who had good credit. It offered 100 percent loan-to-value mortgages with an average size between $200,000 and $300,000 for borrowers who fully documented their income. Dallas says that space in the market, which he had originally pioneered when he ran First Franklin, had always seen low default rates.

Ownit started its life by buying a small mortgage company called Oakmont that had given out about $800 million worth of mortgages per year. “Less than a year later,” recalls Dallas, “we were doing $4 billion and the second year we were doing more in a month than Oakmont did in the entire year of 2003. And that just shows you the insatiable appetite for what we were doing in the marketplace.” Wall Street loved his product and Dallas was now focused on getting bigger.

But when you get that big, you have to find a stable source of those short-term loans called warehouse lines of credit that can fund your mortgages when you make them and before you sell them. Dallas turned to Merrill Lynch for a billion-dollar line of credit. He had dealt with the firm in the past when First Franklin sold it mortgages. Now, Merrill would get into business with Dallas’s new firm, and to cement the relationship, Merrill Lynch bought a 20 percent ownership stake in the private company for $100 million in the fall of 2005. It wasn’t long after that the wheels started to come off.

By 2006, with short-term interest rates hitting multiyear highs and the credit quality of available borrowers moving still lower, Ownit started to loosen its standards. It wanted to prove to Merrill that it had made a good decision in its choice of partner by showing it could grow. But to do so, Ownit started to do loans it had once avoided. “We never did a lot of it, but even doing a little bit was enough to taint the whole ship. When you mix no income verification with low FICO customers it’s a bad mix,” says a regretful Dallas. Making 100 percent loan-to-value adjustable-rate mortgages when interest rates are rising isn’t the greatest place to be, and when you start to loosen your standards, things go downhill pretty fast. At least they did for Ownit.

The business model—and by that I mean how much can you sell the loan for [to Wall Street] versus the risk that you’re taking—was in question. And I can remember having a conversation with my board [of directors], saying, “Look we really have two questions that we have to answer. Do we want to continue to try and take that risk and continue to grow? Or do we wanna shrink?”

The decision was soon made for him. In September 2006, Merrill Lynch bought First Franklin, the first mortgage lender Dallas founded, from National City Bank for $1.3 billion. First Franklin wasn’t seeing (or admitting) the problems that Ownit was, and Merrill was happy to focus its energy on its new acquisition rather than a firm that was still trying to play by the old rules of underwriting. “We shut it down in ’06 because we could not navigate it any longer. And I just said, ‘You know, I’m done. I’ve tried my best. It’s gonna get worse. So we’re out.’ And what people don’t understand is that one hundred percent loans should have gone to ninety-five percent, should have gone to ninety percent. We should had more down payment. We should had more income,” laments Dallas.

In a normal mortgage world, the one ruled by Freddie and Fannie for all those years, when interest rates started going up, mortgage volume should have started going down. And for prime borrowers, that’s just what happened. The issuance of prime mortgages fell sharply in late 2004 and stayed down as the Federal Reserve raised interest rates from the historic low of 1 percent in June 2004 to a high of 5.25 percent two years later. But instead of overall mortgage issuance falling, the drop in prime mortgages was replaced by an avalanche of subprime and alt-A mortgages.

Bill Dallas had been around long enough to know something was amiss. He had never seen a market where volume went up while interest rates did as well. The proliferation of toxic mortgage products and the willingness of Wall Street to buy them created demand that should not have been there and wasn’t during any previous interest rate cycle. Bill Dallas shut down rather than make mortgages that were going to go bad only months after they had been funded.

Back from the Grave

If only our story ended there. But like a horror movie in which a character has avoided a bloody death until foolishly venturing back to the place where the murder was committed, so too did Fannie and Freddie decide it was time to return to the scene of the crime. Their timeout was over and now their managements eyed a market that was no longer built for their rules. As subprime and alt-A loans ballooned to a bigger and bigger percentage of the mortgage market, the risk-management restrictions Fannie and Freddie had in place limited each company’s involvement with those type of mortgages. They might want to once again dominate the mortgage-backed security market, but they were not going to be able to do that unless they could buy most of the mortgages that were being made.

In June 2005, Fannie Mae found itself at a “strategic crossroads,” according to a then-confidential presentation prepared for Fannie’s then-CEO, Daniel Mudd. The document, unearthed by Representative Henry Waxman’s Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, lays out two clear choices. Fannie Mae could either “stay the course” or “meet the market where the market is.”

Staying the course meant sticking with the prime, well-documented mortgages that had always been Fannie and Freddie’s bread and butter. But the real “revenue opportunity,” according to the confidential presentation, was in buying subprime and other alternative mortgages. The presentation acknowledged that investing in the riskier mortgages would bring higher credit losses and exposure to unknown risks. But it would also mean bigger profit margins and it would satisfy their overseers in Congress, who were urging the GSEs to make credit more widely available to borrowers who had not always been its recipients.

Fannie and Freddie were getting bullied by the lenders of Irvine, California, who taunted the two companies with their newfound access to Wall Street’s securitization pipeline. “You need us more than we need you,” was the subprime lenders’ new mantra and Fannie and Freddie took the bait. After all, while they were government-sponsored entities, they were also public companies with a responsibility to drive profits for their shareholders, profits that would also reward their management.

In 2004, Freddie Mac’s chief risk officer sent an e-mail to CEO Richard Syron urging the company to stop purchasing loans that had no income or asset requirements as soon as “practicable.” Freddie had only recently begun some small purchases of these loans, which the chief risk officer warned were targeted to borrowers who would have trouble qualifying for a mortgage if their financial position were adequately disclosed. Syron fired him.

Suffice it to say, as the materials furnished by Waxman’s committee indicate, Fannie and Freddie plunged deep into the parts of the mortgage market they had once avoided. They were also cheered on for doing so by influential congresspersons such as Democratic Representative Barney Frank from Massachusetts. The decision cost them both dearly. Had Fannie and Freddie stayed on the sidelines, they would have had more than a fighting chance to survive the housing market’s implosion instead of being consumed by it.

With Fannie and Freddie back in the game and competing vigorously with Wall Street to buy subprime and alternative mortgages, the pace of securitization hit previously unimagined heights, which meant the amount of money available to these subprime borrowers skyrocketed as well. In 2005, 80 percent of subprime mortgages were being securitized and sold to voracious investors around the world. The subprime mortgage had become a chief export of our country.

Alan Greenspan believes the roots of the credit crisis spring directly from this fact. “Were it not for the securitization and essentially spreading those mortgage-backeds across the world, the subprime problem would have been constrained to the United States. ’Cause I know of no single mortgage that is subprime which is held outside the United States other than in securitized form,” says the former Fed chairman.

The tremendous demand for mortgage-backed securities made up of subprime mortgages had begun at the early part of the housing boom in 2003 and 2004, when rising home prices enabled subprime borrowers to refinance their way out of any financial trouble. The rate of return on mortgage-backed securities from those years was high because people kept paying their mortgages or even repaid them in full due to sales or refinancings.

Greenspan says their mistake was assuming the future would be like the past. “The basic problem that they created was they perceived delinquencies and defaults were very small, as they were in the early stages of the subprime market, because home prices were rising.”

No one ever seemed to ask what would happen if housing prices started to fall.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.