Securing America’s International Business Future: An Overview (with P. Dickson)

Marketing News, April 2016

This first article is longer than the subsequent articles; however, it is still fun to read and, more importantly, guarantees a general overview which will make you understand crucial changes in international trade and marketing.

Twenty years ago, we presented a process-learning perspective on what was needed to ensure that America continues to be a winner in free trade markets and a shining city on the hill. Drawing on how Great Britain lost its lead in the industrial revolution, we proposed several integrated programs to promote the process-learning market. Central to this was the creation of well-paying jobs through superior commercialization of innovation.

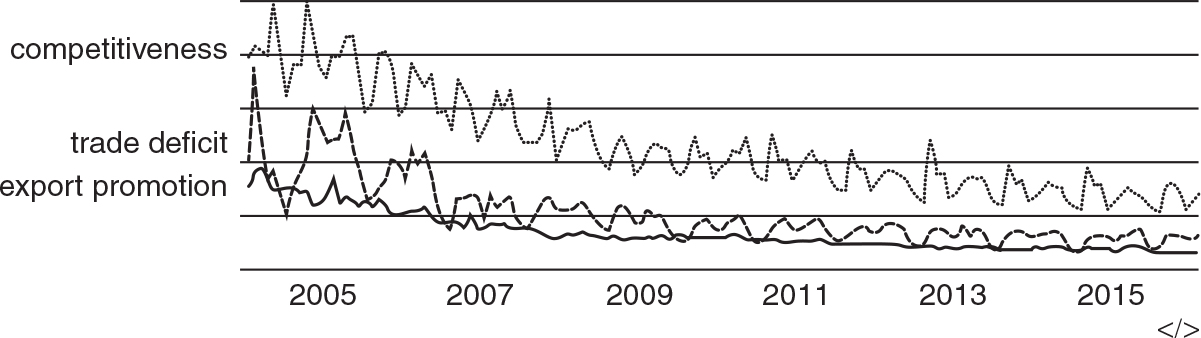

Since then, individuals such as Michael Porter have been outspoken about the need for a major public policy-driven innovation initiative, but little action has resulted. Interest in the topics of learning and innovation has actually declined in public discourse over the past 11 years as measured by Google Trends in Figure 1.1. It should have increased instead.

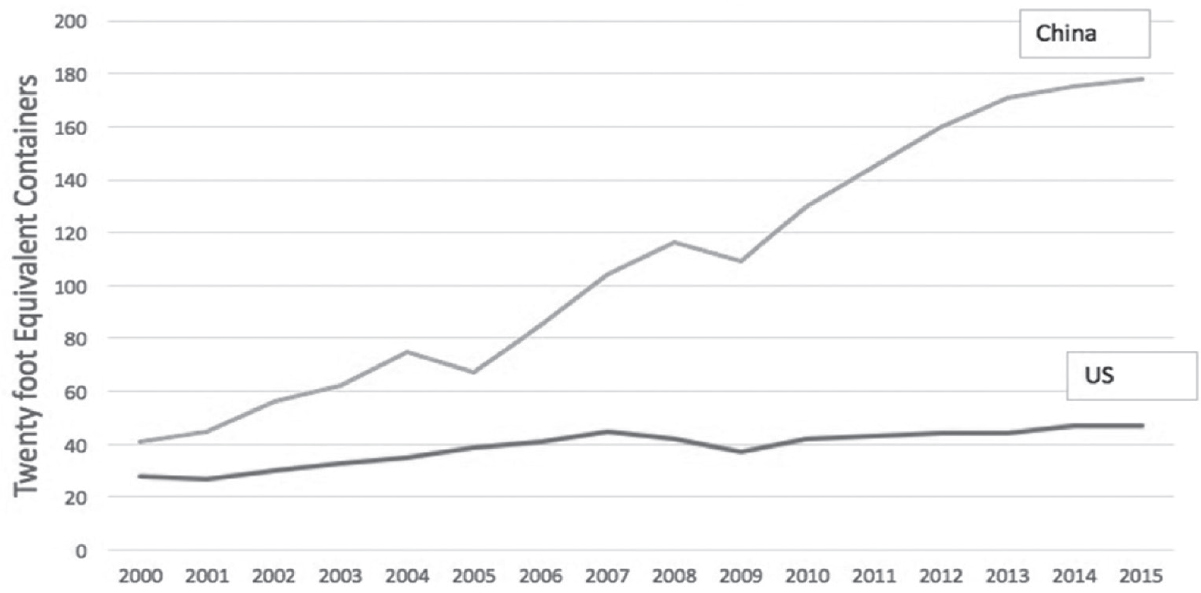

Meanwhile the world has moved on. The extraordinary growth of Asian economies, in particular China’s over the past 20 years has dramatically altered the challenges and raised the stakes. According to the World Bank, in terms of port container traffic, the Chinese economy has grown logistically from being about equal to the United States in 2000 to being four times larger in 2015, as shown in Figure 1.2.

Judging by these traffic flows, a lot more experiential learning is being done in the Chinese economy and it is not just learning how to move containers. It is learning how to develop, market, and distribute new products to the market. Learning-by-doing has made many sectors of the Chinese economy more capable and competitive than their counterparts in the United States. This enormous learning advantage gained by active international traders, many of them from Asia, appears to have been insufficiently recognized by the political and business leadership of the United States. Failure to learn because of not doing will lead to diminished results for the U.S. economy. It will bring lower wages and greater income inequality to the United States over the next several decades. We propose a number of public–private sector initiatives that can be implemented rapidly by a new administration to rebuild the nation’s competence and confidence in its process-learning capabilities and commercialization of innovation. But first the story behind why these initiatives are needed.

Figure 1.1 Frequency of learning and innovation

Source: Google Trends (www.google.com/trends), from 2005 to 2015

Figure 1.2 China and U.S. container traffic, 2000–2015

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators (WDIs), Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and China Port Container official website, February 2015.

How the Business World Has Changed

Much pivots from innovations in transportation, communication, and logistics. The key trade barrier that reduced competition between national economic enterprises was the prohibitive cost of transporting products safely to faraway destinations. The impact of this trade barrier has shifted due to lower tariffs, and better information flows. Declining energy prices contribute to low transportation costs. Innovation has led to higher trade volume. Research has found a positive and statistically significant correlation between innovation and export. Manufacturing and distribution quality control were supported by the innovation of at-a-distance systems controls, such as ISO9000 certification and performance contracts.

As collateral effects, these breakthroughs have accelerated the learning of foreign suppliers, and created cheap and seamless logistic flows between low labor cost (LLC) economies and Western markets. Marketplace technology transfers between developed and developing economies now occur at a breakneck speed. Online tools are the new reality that permit the legal transfer of ideas from innovator to imitator at almost no cost and in real time. Beyond that, the Internet has empowered the theft of intellectual property estimated to cost U.S. companies more than $300 billion per year.

American business ideas support America’s competitors. American higher education transfers its newest thoughts and practices to the world’s knowledge workers as a deliberate business development strategy. American multinational company managers increase owner profits by transferring ideas and value-added processes to their global supply chains and operations in LLC economies. Sadly, the transfer prices typically charged are based on the cost of knowledge replication rather than that of knowledge regeneration, thus providing very little recovery of investment capital.

The Learning Curve Advantage of Imitators

Transfers to offshore imitators reinforce those who already possess a steeper learning curve than the original innovator. An imitator’s learning curve is always steeper than the original innovator’s learning curve. However fast we move into new fields, the rest of the world will catch up faster. As illustrated in Figure 1.3’s learning curve, in many technologies, U.S. businesses are at the top, whereas Chinese businesses are half-way up and thus learning faster and more.

Also, American firms often follow traditional and conservative improvement methods. Many Asian companies in contrast find innovative ways of dealing with new issues, letting them climb even faster.

The advantage, however, flips when American innovation frequency creates new firms, markets, and learning curves. Then, American companies are on the steep part of the learning S curve whereas Chinese and many other Asian start-ups are still at the fermenting stage. One interesting observation here is that younger firms have more to gain than older firms from increasing sales through exports. Sadly, however, U.S. intensity of start-up activity of firms is declining or tepid at best. In some quarters, there is expectation of a growing firm founders’ gap, which causes the United States to fall behind.

Figure 1.3 Business positions on the learning curve

Strategic constraints can, if understood well, also help the success of the underdog. We have established the benefits which Asian imitators can obtain from American innovators. There is, however, no prohibition of an imitation strategy by U.S. firms. We already do so with Indian products and services, such as the radio (1895 in Calcutta) and the discovery of water on the lunar surface (2013), and Chinese products for the Fourth of July fireworks (7th century AD), or, in future, with the Beijing Electron Positron Collider (BEPC) (2016). Any firm or industry that can position itself on the steep part of the “S” curve through imitation can have an advantage above the Overlord. The bottom line: Imitation strategies can work for American firms too!

Experience Curves and Exports

In studying the effect of experience, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG 2016) found costs on value added to go down 20 to 30 percent every time cumulative output doubles. BCG attributes this decline to greater managerial, production, and logistical expertise arising from greater product experience, leading to lower costs. Small firms can rapidly decrease their high initial costs, since their cumulative volume tends to be small and can be doubled and redoubled quickly. Thus, a good way for a new firm to compete with an established one is to increase sales volume rapidly, thus quickly lowering its costs, even if this strategy hurts short-term profits.

Exporting can be a key strategy for new and young firms to do so. By selling outside the domestic market to more customers, small firms gain more rapidly in product experience and decrease unit costs, and are better able to compete with established larger firms. Larger firms, on the other hand, do not have as much to gain by increasing their sales volume through exporting, as they have already obtained earlier significant cumulative outputs in the domestic market.

The Enterprise Development Dynamic

The effects of logistics innovation, accelerated technology transfer, and learning advantage loomed large in the 1980s when American supply chain capabilities leapt forward. The actual cost of distribution as a percentage of GDP declined while the quality of service went up. Distribution bundlers such as FedEx flourished. Many companies rerouted their supply chains through LLC economies to stay price competitive and increase their profits. Otherwise, they were outcompeted and investment dried up.

This shift is not unexpected according to Vernon and Wells, whose product cycle theory concludes that profitable innovations require large quantities of capital and highly skilled labor. Innovating countries increase their exports while competitors exercise downward pressure on prices and profit margins.

For mature products, manufacturing is completely standardized. The availability of cheap and unskilled labor dictates the country of production. Profit margins are thin, and competition is fierce. Exports peak as the LLC countries expand production and become net exporters themselves.

Initiation of production in the United States and the moving of factories abroad can well be done by the same firm. Transfer of production locale may mean a job loss for employees but is not necessarily a loss of competitiveness for the firm. Yet, without any planning for transition, the value of unemployed workers quickly races toward zero. This is unacceptable and explains why re-shoring must become a new preference. Currently, the dynamic progresses through these steps:

1. Western engineers and managers set up production lines that meet desired quality standards in LLC economies. Western technology and manufacturing innovation that fit with the LLC worker skills, work ethic, and costs are transferred to new supply chain partners.

2. With increasing manufacturing experience, both costs and quality defects go down (the experience curve). Supply chain partners innovate processes that increase quality and reduce costs continuously.

3. Goods supplied by supply chain partners start to be sold in the LLC domestic economy at low prices, encouraging local markets and brand growth. Source nations such as China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, and Brazil create new powerful brands that are world class.

4. The new brands are marketed and sold in other emerging markets where they often outcompete established Western brands.

5. The new brands absorb share and profitability in Western economies.

6. New brands become of higher quality and outcompete established brands.

The above development dynamic expands around the globe. Highly motivated, education-focused workers and companies will likely design and deliver better lean products and services to global markets than those less motivated, interested, and educated.

Reality creates not just a labor market problem but also a capital market problem. Investment may continue to flow through and greatly enrich Wall Street, but it will pool where the action is—which is Main Road, PRC, where markets, jobs, and capital are created.

New patterns of trade have, often seamlessly, integrated U.S. interests even without effective industrial policy. Localized competitiveness used to encourage innovation. The United States’ economy remains large, variable and vibrant, and its consumers are loyal to domestic products. In consequence any decline tends to be gradual without a view of the abyss. But the slow, intermittent nature makes the situation highly insidious. Like the slowly cooked frog, who does not notice the rising heat, there is no alarm to trigger broad-based sacrifices in support of decisive action.

Being Great at Certain Things

Here are some possible remedies.

1. Rapidly increase the number and proportion of new firms.

2. Encourage and assist with the cost of training process improvement expertise. Highlight innovations that have systemwide effects.

3. Sponsor research and training centers focused on supporting new processes, such as big data analysis through cross-collaboration for example, between the Commerce Department, the SBA, the International Trade Commission, and AID.

4. Have public and private sectors jointly create pop-up research centers that better train process improvers, and domestically distribute insights of companies that innovate successfully.

5. The Commerce Department should assert its communication role by patronizing an annual case competition with key examples of how international business obstacles have been creatively overcome through process innovation.

6. The U.S. Commercial Service should identify key global innovators, from whom it can acquire process information and distribute such as a clearing house or seminar coordinator both for American innovators and imitators. Government servants had to learn for more than a decade that service exports are just as good as exports from manufacturing plants. Now, they must learn to appreciate American imitation and support it as an information-clearing house, and perhaps even through export fireside chats. While we strongly support the gathering and distribution of targeted information focused on interested firms, we do not support the selection of winners and losers.

7. There is a need for an ongoing thrust in support of innovation—maybe through an Innovators’ Day, when firms can brag a little and crown their key contributors to innovation. There could even be innovation competitions in schools, reminiscent of spelling bees, and an annual School District innovation runoff.

There is nothing demeaning about supporting business which has made America great! Government, firms, and employees need to write a new history. Training and support of knowledge workers who help to commercialize American innovation, imitation, and incubation is crucial. It is imperative to periodically evaluate how support and funding for international business programs translate into success. The goal is to increase American knowledge workers’ likelihood of producing innovative goods that outsell global competition, allow America’s economy to adapt and move into newer fields quicker and more successfully than anyone else, and ensure that the American economy profits from freer trade.

Innovation Scholarships can be awarded to local students and faculty with the best commercializing innovation ideas for the three business sectors most important to each state’s economy. Of crucial importance is to not let such awards become captive to one interest group. Rather, there must be an early cross-fertilization between fields, for example venture capitalists, successful academics, service experts, and engineers. University business incubators have been successful in cultivating exactly such an environment. The Halcyon Incubator floated by the S&R Foundation is just one example of this success. The sponsorship of a meaningful number of scholarships would consume only a fraction of the savings achieved by forthcoming U.S. base closures in Europe.

Each team will nurture a start-up business venture around the central innovator’s idea. Higher education should be expected, using its own endowment funds, to invest in a portfolio of job-creating business ventures. These should be limited to 2 years for any given project and end with a major attempt to secure crowd funding. Concurrently, a series of innovation and imitation presentations, starting at the local level and continuing upwards, can enlighten and encourage supporters and participants. Such collaboration between fields and facility has already been applied quite successfully in Germany.

Figure 1.4 indicates the necessity for and a benchmark of some key terms: trade deficit, export promotion, and competitiveness. They reflect the positioning for the U.S.’ international business policy actions and outlook. While the apparent loose correlation between the three factors in general appeals for a partial linkage between them, we find the downslide, which occurred for all three factors during the past 11 years, to be quite troublesome.

Figure 1.4 Frequency-of-mention: trade deficit, competitiveness, and export promotion

competitiveness: dotted line; trade deficit: dashed line; export promotion: solid line

Source: Google Trends (www.google.com/trends), from 2005 to 2015, e.g. Google Trends (www.google.com/trends) on Trade deficit, competitiveness, export promotion, from 2005 to 2015.

In summary, we recommend a sustained decade-long deployment of government and higher education resources to provide incentives that encourage planning and training for the facilitation of creating additional, younger and more internationally oriented firms. The firms then must be provided with dedicated workers and a supportive broad-based educational infrastructure, and successful management capable and willing to innovate, imitate, and internationalize. The youth of this nation must again think of progress in terms of internationally commercializing its work. After all, they are the future!