Chapter 5. Engaging with Your Web Visitors through More Targeted Search Referrals

On the Web, you do not address a generic passive audience; you engage a defined active one. That engagement starts with attracting a targeted audience with keywords, as we explained in the previous chapter. But it doesn’t end there. Search engines can help you attract a targeted audience, but once you get that audience on your site, you need to engage them with compelling links. This chapter is about helping visitors understand how to engage with your content, so they can use it to find what they need.

Making your audience engage deeply with your content has two main components. The first is a common consideration for all writing, which is especially important in Web writing: purpose. The most important thing about purpose is that content can be relevant to an audience in one visit and not in the next. Why? Because your visitors’ information-related needs change as they consume it. Content that readers find redundant is also irrelevant to them. Helping users find fresh content on topics of interest is both a challenge and an opportunity for Web publishers. This is another way that Web publishing differs from print. Print publications are complete. They either serve the intended purpose or they do not. But Web sites are always incomplete: If you find that your pages can do a better job of serving their intended purposes, you can and should change them.

Purpose is only the most important variable that affects how to create relevant experiences for Web audiences. As you know, natural language is quite complex, involving many other variables that affect relevance. You can simplify the problem by focusing on keywords, but you don’t want to oversimplify it in the process. We can help you understand how keywords and phrases affect the overall content of your pages, so that your site can engage visitors more deeply. The second half of this chapter shows how you can engage more deeply with your audience’s use of language. These methods include knowing their long-tail keyword habits in their search behavior, and discovering your audience’s writing and tagging habits in social media. If you know your audience at a deeper level, you can more deeply engage with them, by using their language when you write.

Using Page Purpose to Engage with Your Audience

Consider the following scenario. A user searches on an IBM product name and lands on an ibm.com marketing page for that product. The user already owns the product, but wants to find support pages for it. So even though the page’s topic is relevant to the visitor’s search query, the page itself is not. Why? Because the page’s purpose did not match the user’s interests. In fact, ibm.com receives many “Rate This Page” surveys in which people describe precisely this experience, essentially saying “Stop selling me a product I already own!” Our company’s marketing department works very hard to optimize its pages for search and garners the majority of the search visits for product names. It does this even though we know that 60 percent of ibm.com visitors are looking for support for products they already own.

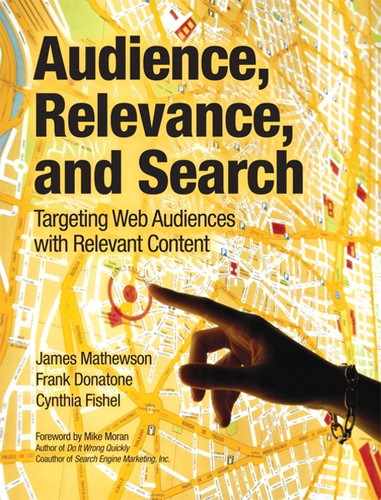

This illustrates the importance of including a page’s purpose in its keywords. This is important for different functional groups, such as marketing and support. But it’s also important within individual functional groups. For example, on a page that falls under marketing’s responsibility, one visitor might want to learn how to solve a particular problem with IBM technology, while another wants to look at what technology offerings might help solve the problem. In IBM we call the first purpose awareness and the second one consideration. Awareness pages tend to be more relevant for visitors who are trying to solve a problem, while consideration pages tend to be more relevant for those who want to compare and contrast potential solutions to a problem.

Some pages that are relevant to the same keywords are designed to help visitors with different purposes consume the same content. These generic landing pages are useful, but you only need a few of them. Most of your content will need to have a basic defined purpose for each page. To avoid negative user experiences like those shown in some of IBM’s user surveys, you’ll need to develop content that makes its purpose explicit in the title tag, as well as elsewhere on the page.

In some fields, this process is called task analysis—a term borrowed from software engineering—in which you develop use cases and make sure your pages accommodate most of them. A use case is a scenario in which a user experience (fictional or otherwise) is described. Most pages have several use cases; entire sites might have more use cases than can be enumerated. You can never anticipate your visitors’ every move. But, as we have said repeatedly, the beauty of the Web is that you can adjust your pages for the users who come to them. So even if you do not anticipate all the paths your visitors might take, you can follow their movements and make it easier on them as time goes on, by adjusting your experiences to suit their needs.

Though task analysis can help you engage with your visitors after they come to your pages, you can also precondition them by helping them land directly on the pages relevant to their tasks when they come from search engines. Along with having keywords that describe each page’s topic, be sure to include each page’s purpose in the keywords in its title tag, heading, and URL. The tasks that we use in marketing contexts (which we elaborate on in the sidebar) are borrowed from the sales cycle, including awareness and consideration. For example, perhaps you have one base keyword phrase, say Service Oriented Architecture. You should then add a purpose to each page’s title tag, such as Service Oriented Architecture: Learn About and Service Oriented Architecture: Compare Products.

Suppose your site promotes smarter healthcare and has two stories about patient information management. One page could be about the generic concepts (such as defining the problem or describing the solutions at a high level). Here, users’ engagement is directed to information that gives them awareness. Other pages on the site might direct users to take action to find the particular solutions that matter to them. In particular, you might have a section for hospital administrators to evaluate products. This would be at the level of consideration.

Even when coming to pages with the same content topics, visitors may have a wide variety of purposes and tasks in mind. We can’t say this too often: The way to differentiate these pages for Google users is to state each page’s purpose clearly in the title tag, heading, URL, and abstract. In the abstract, tell users what you want them to do when they get to your page. In the above example, the keyword phrase might be medical information management. Perhaps that is also what you use in the awareness-level page. But in the consideration-level pages, you can add purpose qualifiers. For example, the lower-level pages might have the keyword phrases medical information management—evaluating patient privacy solutions, or medical information management—evaluating portable data solutions. And you could have a number of pages with different verbs in them, like purchasing, supporting, extending, and integrating. If portions of your target audience are interested in these different purposes, consider building such pages a click or two off from the generic landing page.

You can also precondition users by making sure that the page purpose is in the metadescription (<meta content="description">) in your page code. This will end up in the short description or snippet that search engines display in the search engine results page (SERP). Users who read this snippet will have a better idea of the page purpose before they land on your page from Google or other search engines.

We will discuss how to build site architectures using keywords as each page’s reason for being in Chapter 6. Considering purpose through task analysis is one of the prime ways to create an engaging site architecture. But to build a complete site that engages your audience at a deep level and keeps them coming back again and again in search of relevant content, you need to look deeper than just purpose. You must explore the depths of your audience’s vocabulary: not just their keywords in isolation, but their keyword clouds, and the myriad grammatical constructions they could use to combine keywords into meaningful sentences.

Going beyond Mere Keywords to Determine Relevance for an Audience

In the previous chapter, we assumed for the moment that all you know about your audience on the Web is that they came to your page from Google using a keyword string. But you often can know more than that. If you develop a deeper understanding of the language your visitors use—not just vocabulary, but also phraseology—you can engage more deeply with them. The rest of this chapter is about learning about your audience’s language use, in a way made possible only on the Web: through participating in their favorite social media sites.

A user can find the content on a page (with the same keywords) relevant one week and irrelevant the next. You might ask: How can this happen? If keyword usage determines relevance, how can attracting users to your pages though keywords sometimes drive them to irrelevant information? Well, language is a lot more complex than a simple matching algorithm between keywords and users. If it were that simple, Web writing and editing would be a matter for technology and not humans. But humans are needed to make good content decisions based on a variety of variables, including keyword usage.

What variables other than purpose affect whether content is relevant? One key variable is content freshness. All things considered, content that is up to date will be more relevant to users than stale content. But this is not an either/or proposition. There are degrees of content freshness. Also, not all content needs to be fresh. The relevance of news falls off quickly after it is published. On the other hand, product specifications retain freshness for a long time. Users have different expectations of freshness for different types of content. A podcast is expected to be recent, whereas certain white papers are evergreen, meaning that they stay fresh indefinitely. Fortunately, it is not hard to find out your users’ expectations of freshness for each content type. You can even set up systems that tell you when a piece of content has expired and automatically take it down.

There are many more variables that affect relevance than we have space to enumerate. That is for linguists to deal with, rather than writing instructors. But we can point you to a few additional ways to learn how your audience phrases their needs, so you can better meet those needs with relevant content. You can do more sophisticated long-tail keyword research, using what we know about how search engines determine relevance for longer queries. And you can learn more about how your audience writes and responds in social media settings. These two tactics are the subject of the rest of this chapter.

Using Keyword Research to Optimize for Long Tails

What are long-tail keywords? They are not necessarily longer strings of keywords, as you might think. The term The Long Tail was coined by Wired magazine’s editor Chris Anderson in an article in 2004 (and elaborated in 2006 in his book by the same name). The Long Tail is a marketing concept in which companies sell small volumes of hard-to-find items to high volumes of diverse customers. One example of this model is Etsy.com, a cooperative site for people who create niche crafts such as jewelry. This is in contrast to a company that sells high volumes of just a few popular items, as Dell does. The Long Tail actually refers to the demographics of people with highly specialized, diverse needs—Etsy.com visitors, for example. The concept has been extended to keywords. Long-tail keywords are like hard-to find items—longer key phrases that users take the trouble to type in when they want to find something quite specific. This is in contrast to popular search words, which are highly coveted by marketers because they will draw high volumes from a relatively narrow demographic.

So far we have helped you optimize for conventional high-demand terms. This section is about capturing the long-tail demographic—diverse audiences who have unique interests in your content. This is yet another way in which Web publishing differs radically from print. In the print world, you don’t get a book deal unless the publisher is convinced that the book will sell in relatively high volumes. Magazines go out of business unless the readership is large enough for advertisers to want to buy ads. On the Web, Etsy.com is an example of a very successful model. Any individual page on that site might only get ten visits per month. But the sheer volume of pages, and the depth of engagement by its users, enable Etsy.com to make money and continue to serve its constituents.

From a keyword perspective, long-tail keywords are basically an expansion of a core, generic, high-volume keyword phrase. These expansions typically include numerous combinations and permutations of high-volume keywords and their associated or relevant phrases. But they need not be longer than the original high-volume keyword. They can just be unique ways of phrasing variations of it.

According to doshdosh.com (www.doshdosh.com/how-to-target-long-tail-keywords-increase-search-traffic/), these long-tail keywords tend to be much more targeted than general or main keyword topics because they literally embody a visitor’s need for specific information. Taken individually, these phrases are unlikely to account for a large number of searches. But taken as a whole, they can provide significant qualified traffic. The main advantages to optimizing pages for long-tail keywords are increased visibility and better audience targeting. Even though individual long-tail keywords do not have high demand in Google—since few people actually search on them—they produce a lot of traffic, because there are so many of them. Long-tail keywords tend to help with targeting because visitors who use such specific search phrases tend to be looking for exactly what they will find through long-tail searches.

According to Aaron Wall of SEO Book (see www.seobook.com/archives/000657.shtml), by conducting a careful analysis of Google results and ranking pages, you can see how semantics plays into Google’s ranking algorithm. The following italicized passage, which gives some of Wall’s most important ideas, is taken directly from the seobook.com page mentioned above.

Nonetheless, it is overtly obvious to anyone who studies search relevancy algorithms by watching the results and ranking pages that the following are true for Google:

• Search engines such as Google do try to figure out phrase relationships when processing queries, improving the rankings of pages with related phrases even if those pages are not focused on the target term

• Pages that are too focused on one phrase tend to rank worse than one would expect (sometimes even being filtered out for what some SEOs call being over-optimized)

• Pages that are focused on a wider net of related keywords tend to have more stable rankings for the core keyword and rank for a wider net of keywords

When Wall speaks of “a wider net of keywords” What he means by this is capturing long-tail keyword combinations. Some pages have so little copy that it is very difficult to optimize them for anything but the chosen keywords. We recommend a minimum of 300 words on a page, which allows you to write about your topic in greater depth. This will give you more opportunities to use different word combinations and grammatical constructions related to the same topic. But don’t be redundant just to get multiple long-tail combinations into your copy. And don’t skimp on copy just because you just want to satisfy the scanners in your audience. There are ways of convincing scanners to read. Scanning and reading are not mutually exclusive. True, Web users tend to scan before determining if a page is worth their time. But once they determine that they want to read it, they’ll read between 300 and 500 words. Make sure that you give scanners the contextual cues they need, such as bolded words and multiple headings that include keywords, but don’t short change the readers either. If you satisfy both types of visitors, you’ll have a better chance of capturing traffic from long-tail demographics.

In our own work optimizing pages for ibm.com, we encounter the following scenario over and over. We look for relatively high-demand keywords with relatively low competition. Then we optimize pages with the keywords we chose. Our traffic to those pages might go up exponentially, but this increase is not clearly linked to the keywords we chose. We might not rank well for those words because of higher competition—it takes time to build sufficient link equity to rank well for terms with a lot of competition. But nonetheless, we get good search referral data, because users are coming to our pages from long-tail variations of keywords we chose. The reason is that in addition to optimizing for our chosen keywords, we also optimize for several related strings of words. Some of this happens naturally: Good writers tend to vary their usage patterns with the same root words to break up the monotony. But some of it is planned: We expect writers to consciously stem verb forms, to use variations of the same noun, to use synonyms, and to try to use keywords in different parts of speech. All of these writing practices cater to searchers who come to your site using long-tail keywords. The good news is that people who use long-tail searches are more apt to find your content relevant to them and are less apt to bounce off your page.

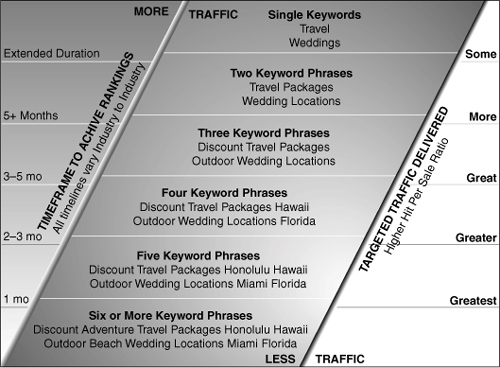

According to Stoney deGeyter (2008), a leading expert on keyword research and selection from Pole Position Marketing, Web writers should focus on word strings two to four words long when trying to target their audience through long-tail keywords: “In general, terms with two to four words are the best. With two to four words, each search term can be both descriptive and specific. If a specific term is typed into the search engine and your site appears, the searcher knows you have precisely what they are looking for.” (See Figure 5.2.)

Figure 5.2. The long-tail keyword time to market and targeted traffic matrix.

(Source: deGeyter 2008)

When it comes to keyword usage, the goal is to find the right combination of words to attract a more targeted audience and to engage them with the phrases they use to describe things. In marketing contexts, it costs money to optimize for high-demand words, especially those with a lot of competition. But if you optimize for long-tail keywords, you can get a much better return on investment with a smaller number of qualified visitors than you would with a large number of unqualified visitors coming to your site from high-demand keyword searches. And you can optimize for long-tail keywords more quickly than for high-demand words. This enables you to engage with your target audience almost as soon as you publish your content.

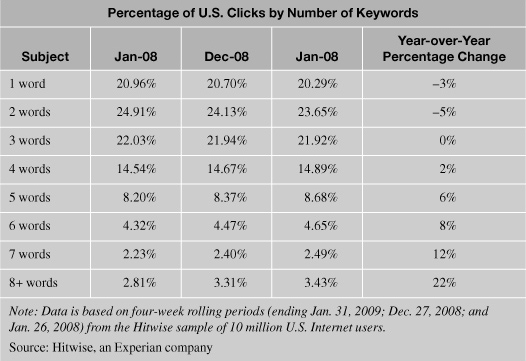

The other thing to keep in mind about long-tail keywords is that as users become more search-savvy, the trend is toward longer tails. As they learn how to zero in on relevant content through search, users form their search strings in more sophisticated ways, typically with three or four words. Recent research from Hitwise confirms this trend, as noted elsewhere by Matt McGee (see http://searchengineland.com/search-queries-getting-longer-16676).

More than half of all search queries are at least three words long, and more than a third are four words or longer.

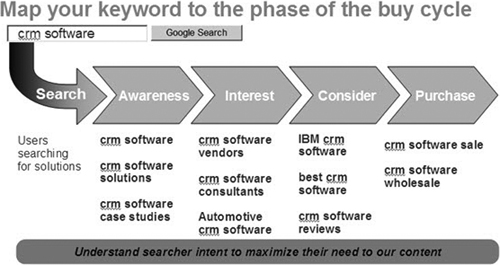

As users become more familiar with the use of search engines, their queries become more specific, and therefore are longer (Figure 5.4). McGee adds that The takeaway point here is that the so-called long-tail of search continues to get longer. As searchers get more sophisticated in how they use Google, Yahoo, Live Search, etc., it opens up more opportunities for webmasters and marketers to create content and ads that capture these longer search queries.

Table 5.4. This chart from Hitwise shows how over time, click-throughs for longer search queries have increased. (Cited by Matt McGee at http://searchengineland.com/search-queries-getting-longer-16676)

Writing for long-tail keywords mostly follows naturally from writing good Web copy. Don’t use the same constructions over and over, but vary them, using synonyms and different grammatical combinations to communicate related concepts. And don’t skimp on body copy. If you understand how your audience is coming to your pages through long-tail keyword combinations, you can edit them to include the combinations that your audience enters into search queries. This helps you to grow a highly targeted audience.

Using Social Media to Enhance Your Audience Understanding

You can define the audience you want to attract by using the combination of research methods outlined in the sidebar “Using the Power of the Web to Better Understand Your Audience.” But that definition never completely captures the audience that comes to your site and finds your content relevant. After you publish your content, people will come to your site who you never expected would find your content relevant. How do you get to know these folks better? We recommend letting your audience contribute to your site by commenting on your content. You could do this through a regular blog, polls, or by having a comment feature added to all articles or stories. These social media tools can really help you learn about and engage with your audience at a deep level. This is one of the emerging aspects of the Web that has accelerated its evolution away from print.

With so many tools available, many site owners throw content against the wall and hope it sticks to some of the folks who come to their site. With modern tools such as polls and blog comments, that can work, as long as you commit to adjusting content to your audience’s needs as you go. But we hope you aspire to learn more about your audience before they come to your site. If it works to gain more information about your audience through their comments on your site, why not try to learn more about them through their comments, tags, social bookmarks, and other activities on other sites that include social media functions? This section discusses tactics for mining social media sites to learn more about your target audience, so that you can create more relevant content for them when they get to your site. If you also include social media functions on your site, you can do a better job of adjusting your content to these users.

In speaking about social media below, you will continually see terms such as tags, tagging, notes, and bookmarks. When they visit sites, people use tags or bookmarks so they can easily return to a given page. These can give you some insight into what words are most popular and into how users build queries. This builds on your knowledge of the keywords that people use when they search. Further, in some cases, these social media tools can show the semantic relationships between words. The keywords that you can glean by exploring social media tools and sites can give you valuable insights into how users perceive your products, services, and content. These will allow you to further understand trends and collect competitive data.

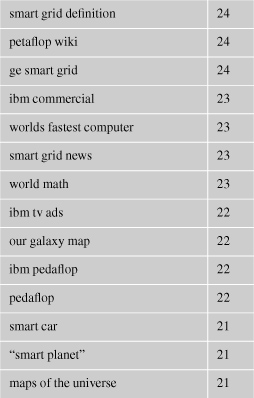

Many sites that feature social tagging to help people find items posted by like-minded users use the tag cloud interface (see Figure 5.7). We recommend that you enable social tagging on your site, to find out how people tag your content. We also recommend that you look at competitive sites’ implementations of social tagging and see how their users tag content. When you develop keyword clouds as part of the set of seed words in your keyword research, you can compare those to tag clouds to find similar relationships. The basic idea is that tag clouds and keyword clouds are very similar. They both include sets of related words used by Web site visitors to find and catalog content for easier retrieval. If users tag content with some words, they are likely to use the same words in their keyword searches. For example, in the sidebar on tools, the tag cloud generated by Quintura can be used as part of your keyword research to generate a keyword cloud.

Figure 5.7. A typical tag cloud interface. Content producers tag pieces of content (in this case RSS feeds) and the application displays the content most often tagged with the same words. Users can slide the bar at the top to display more or fewer tags in the cloud and click and add tags of interest into their personal RSS feed folders.

(Source: www.ibm.com)

Examples of social tagging or social bookmarking sites include digg.com, delicious.com, and flickr.com. IBM is experimenting with using social tagging to help users find content (see Figure 5.7). We plan to mine this tagging data for our keyword research. In addition to tag clouds, we recommend checking out sites with stable social tagging functions, especially www.delicious.com/tag/, a social bookmarking site that lets you see if your keywords are being used as tags and lets you view other complementary tags. Another nifty function at www.delicious.com/url/, lets you see if your URL is being tagged.

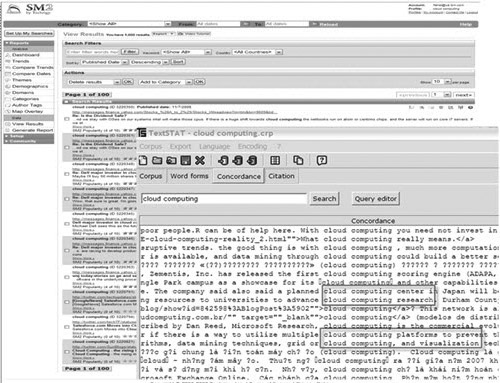

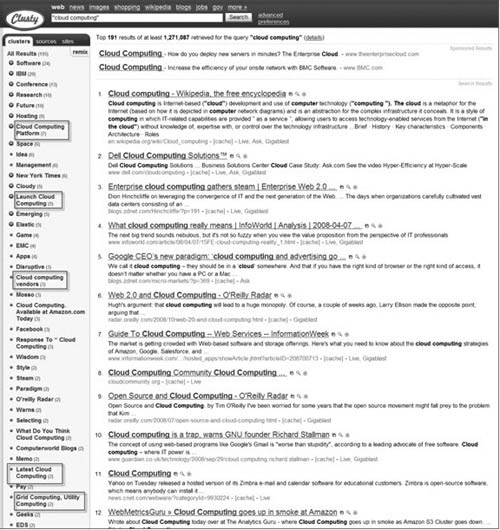

As you can see from the sidebar, social media analysis tools like Alterian SM2 can help you see how people construct their queries. This can give you insight into word patterns, which ultimately helps you create your long-tail keyword patterns. You can also conduct local SEO through keyword analysis by using tools such as Clusty, a social media search engine (Figure 5.9). For a given keyword phrase that you enter, Clusty queries several top search engines, combines the results, and generates an ordered list of those keywords, based on comparative ranking. This “metasearch” approach helps raise the best results to the top and push search engine spam to the bottom.

Figure 5.9. Clusters help you see your search results by topic so you can zero in on exactly what you’re looking for or discover unexpected relationships between items.

(Source: www.clusty.com)

In Clusty, you will find categorization or “clusters” (or topics) in the left navigation bar. These may help you see keyword possibilities that you might not have considered otherwise. Clusty also has a “remix” feature that allows you to see one level deeper for other submerged related topics. Using these words in your content will greatly help you increase the relevance of your site.

Summary

• Basic SEO only explains a small part of the opportunities that you as a Web content publisher have to provide relevant content to your audience.

• Beyond mere keywords, page purpose is a key element. Users who find your topics relevant one day might not the next if they come to your site with a different purpose in mind. Awareness and consideration are two common purposes in marketing contexts.

• Beyond purpose, you must take several linguistic variables into account to better connect with your audience. Use can use word patterns located from search engines and tools as alternate primary keywords, secondary keywords, or as the core of long-tail keywords.

• Using long-tail keywords can lead to better engagement by attracting people who are deeply interested in your topics. Multi-phrase search queries generally target more interested, potential customers.

• Because there is less competition for multi-phrase search queries, use them to help your long-tail keywords rank better.

• Use social media functions to learn more about the users who find your content through search.

• As important as it is to connect with users who come to your site, it’s even more important to use social media functions such as social tagging and bookmarking to validate keyword research with tag cloud research.

• Use keywords located in social media posts to gain insight into search query constructions and patterns. By using social media tools, you can see how your audience is using your keyword terms. You can also see how others are searching, what other words are being used in conjunction with your keywords, and other word possibilities.

• To optimize your pages for search, use words that your target audience or competitors use.