Chapter 6. Developing a Search-Optimized Site Architecture

So far we’ve focused on how to fill Web pages with relevant content for your target audiences. Of course, your pages don’t exist in isolation. Preferably, you develop a Web site full of pages as one orchestrated user experience. Your users expect a site with high-level information on the top-level landing pages. And these landing pages lead users to more detailed content, depending on their needs. In this way, your Web experiences are flexible and interactive, giving users the ability to choose exactly the information that is relevant to them.

As noted earlier, this is another way in which Web publishing differs from print publishing. In print, you develop the flow of information and the reader must adapt. Sure, readers can skim and skip sections. But a print publication is designed for linear, serial information processing. The information in one section or chapter builds on previous sections or chapters (as in this book). Print publications have their place. The writer presumes that the reader does not know the information with enough depth to predetermine the optimal information flow. Print readers give up control of information flow and read serially, sometimes consuming marginally relevant content in order to grasp the fullness of a topic.

But on the Web, users are in control. According to Jakob Nielsen (May 2008), readers who scan take an average of 3 to 6 seconds to determine whether a page of content is relevant to them. If it is, they spend an average of 26 seconds consuming the information on that page. Clearly, they have a low tolerance for consuming marginally relevant content. Our goal is to give them easy options to traverse our information in non-linear, interactive ways. This can be a challenge, especially when you consider that an increasing percentage of your visitors arrive in the middle of your site’s experience from search engines. It’s easy enough to design experiences if you presume that users come to your other pages from your home page—the front door of your site. But how do you account for users who enter through the side door (from Google or other search engines)? Though you can’t anticipate your users’ every move, you can at least provide cues to help users navigate both to higher-level (more basic or foundational) information and to lower-level (deeper, more detailed) content.

Besides helping visitors find relevant content, having a clear site architecture tends to improve search results, for two reasons. First, internal links improve a page’s PageRank—the part of Google’s algorithm that ranks pages higher if they are linked to other relevant pages on the Web (see Chapter 7). Though not as important as external links, Google will give you credit for links into your pages from highly relevant pages within your site. Second, the Google crawler mimics human Web navigation, following links in its path through your content. If you design a clear site architecture, you make it easier on the crawler and help ensure that the crawler will find your content and pass its information to the search engine.

Many site owners assume that having a clear site architecture is enough. But developing site architecture for visitors coming from search engines goes a step further. Your primary goal is to help users find the content they need with the fewest number of clicks. Clear site architecture helps them get to relevant content even if they land on a page that is not exactly what they want. And search-optimized site architecture helps them land directly on the most relevant pages in your site. That is the ideal situation for the user, requiring the fewest number of clicks to get to their destination. Search-optimized site architecture starts with keyword clouds and organizes pages around the keywords most relevant to the target audience for each page. In this way, keyword research can tell you not only how to create pages, but whole-site experiences with no gaps or overlaps in the content organized by the clouds of keywords that are most relevant to your target audience.

For a variety of reasons, having a search-optimized site architecture enables your target audience to find relevant content with a minimum of clicks. Web writers, editors, and content strategists need to understand the principles and best practices of effective search-optimized site architecture if they hope to consistently connect with their target audiences.

Developing Clear Information Architecture

Information Architecture (IA) is a discipline in which practitioners analyze intended information tasks and design experiences to make those tasks easier. The discipline touches all areas of information management, including but not limited to library science, software application development, technical communication, and Web development. Each field practices information architecture slightly differently. In Web development, the focus of information architecture efforts is Web usability, of which Nielsen (1999, 2001, 2006, 2008) is a leading practitioner.

Web usability is often divided between two primary fields: design—how a site looks to the user—and navigation design—how the visual elements that users interact with on the screen moves them through a site experience. Visual design gives users the cues they need to understand how to move around in a site. In particular, if users know where to find navigation items on every page, they will at least know where to look for relevant content from any page in your site.

Visual design is important, but for the purposes of a search-optimized site architecture, navigation design is what distinguishes a good Web user experience from a poor one. A site might have a clear page layout, with easy links and icons that give users an idea of what they can expect when they click on them. But if the links don’t move them to the content they need, they will eventually abandon the site. Also, search crawlers focus on metadata and text, ignoring visual design. How easy it is for crawlers to find your content determines whether they can index all your content. Even the best visual design can’t make up for dead ends, circular paths, or other navigation mistakes.

Navigation design typically begins with task analysis, in which designers try to think of all the ways the target audience might need to use the site’s information. Task analysis leads to flow diagrams and wireframes, visual representations of a site based on flow diagrams, which spell out how to make these usage patterns as simple as possible. Task analysis is related to page purpose (covered in Chapter 5)—in the sense that every page on your site must have a defined purpose that supports a node in your site’s wireframe. Every node has a defined task, which is defined by the page purpose.

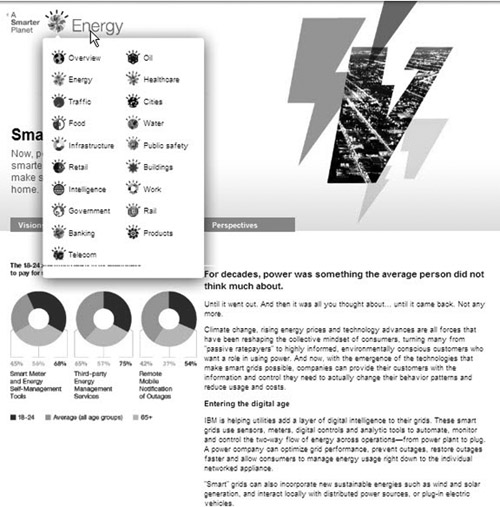

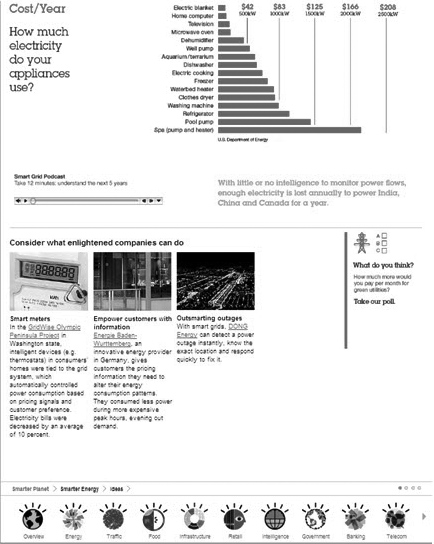

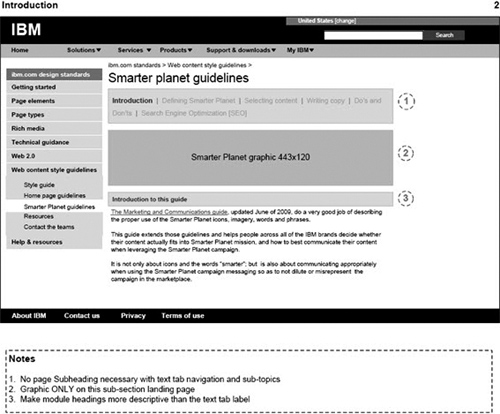

In Chapter 5, we discussed common marketing page purposes, such as awareness, consideration, and interest. When designing a site for audiences interested in a certain product, it is important to serve them the information on that product at the appropriate place in the sales cycle. This is an example of how the scenarios you develop must consider how users move from one page purpose to another, as their tasks demand. Figure 6.1 shows a typical flow diagram of a simplified marketing site experience. Figure 6.2 translates the flow diagram into a wireframe document.

Figure 6.1. Flow chart of Smarter Planet Standards sites with different user tasks.

Figure 6.2. Wireframes from the flow diagram.

If you combine the visual design with navigation design, you get what we call a site’s architecture. This consists of domains, main categories pages, and subcategories pages. These pages are also related to the media assets for which they serve as a conduit, such as videos, podcasts, PDFs, presentations, documents, and audio files.

The above process works for cases in which you are trying to re-architect an existing experience, as we describe in the Smarter Planet case study (see sidebar). In the case of Smarter Planet, we were fortunate that the content did not need a major overhaul. We just assigned new keywords to the existing content and the experience was ready to go for the new content as we added it—about half way through the content plan. But what do you do when you need to develop a site architecture from the ground up? In that case, do you start with a content plan, and try to see how the pages within the plan interrelate before developing the flow diagrams and wireframes? Or do you start with the flow diagrams and wireframes and develop a content plan to fill the pages with compelling content?

In our experience, it is usually better to start with the content plan and develop your architecture from it. As the old adage says: Form follows function. Start with a content plan, including items such as your audience, topic, page purposes, and calls to action. Then develop your site architecture to suit the content plan. But when you have the site architecture done, you will need to fit your content to the page templates according to the design, and it might not all fit just right. So you go back and tweak the architecture to allow your content to grow to suit the needs of the audience. And perhaps along the way, you discover gaps or potential overlaps that you did not consider when you developed the content plan.

It is not uncommon to go through several drafts of the site architecture and content plan before publishing. Even then, when you start measuring the results of your new Web site, you will find room for improvement, and places where adjustments are needed. Visitor data will tell you a lot about the effectiveness of your site’s experience for your audience. Perhaps user feedback will cue you about an unforeseen gap. Or there may be an apparent conflict between two similar pages. Like most things in Web publishing, developing a clear site architecture based on a content plan is an iterative process. And as in most other areas of Web publishing, you can come closer to your target and reduce revisions if you develop your content plan and site architecture with search engines in mind.

Developing Search-Optimized Information Architecture

Developing clear site architecture is part of the basic blocking and tackling of Web development. If you’re familiar with Web publishing, nothing that we have presented so far should surprise you. But we think clear site architecture is not enough. It’s all well and good to have clear paths to the content on your site. This enables visitors to find relevant content even if they came from Google and landed on a page that was not directly relevant to what they were trying to find. But it’s even better if you can design your site architecture to make it more likely that they will land directly on pages containing the content they’re looking for. This is what we mean by search-optimized site architecture.

Just like ordinary clear site architecture, search-optimized site architecture starts with a content plan. But a search-optimized content plan starts with keyword research. From a keyword cloud that is highly relevant to your topic and target audience, you can develop a content plan that covers the cloud completely, without overlap.

Think of a Web site as being like a grocery store. It’s ideal if you carry everything your customers want, and nothing more. They don’t have to go to other stores to find what they’re looking for. And you don’t get left with inventory they won’t buy. In grocery stores, organizing the aisles into logical product families (and facing the products for easy visual retrieval) will ensure that the customers can quickly find what they need. If they don’t, they will leave in frustration to look in another store for the products you carry.

In Web development, content modules are like the products in a grocery store. And pages are like the aisles, in which you organize and face similar content modules, by category, to users. You want to try to develop exactly the content your target audience needs. If you have too much “content inventory” on your shelves, it can actually make it harder for your audience to find what it needs on a topic (not to mention the cost of developing the excess content). If your shelves are bare or lack key content your visitors need, they will go to a competitor to find it. And if your content is not organized in a logical way, they might leave your site in frustration before they find the content you have so painstakingly developed.

We suggest that the most logical, semantic way to organize your content is by keyword relationships. Keyword relationships can help you understand to what extent pages of content are relevant to each other.1

1 To be clear, content is only relevant to visitors, not to other content. But we say that content is relevant to other content as a short cut for saying that a visitor finds both pieces of content relevant and judges that they are related. For example, two pieces of content on the same product are relevant to each other because visitors can grasp the product-level relationship between them.

Given enough time and attention, visitors could find any piece of content relevant to any other. But their time and attention span are short. To feel that two pieces of content are sufficiently relevant to each other to be worth their time and attention, visitors must see this quickly. But how can you predict how well visitors will correlate different pages of content on the same site? The easiest and best way is to look at how they use keywords and see what relationships they grasp between pages with keywords in the same cloud or family.

Not coincidentally, starting your content plan with keyword research is also the most effective way to attract a highly targeted audience from search engines. Your site visitors are individuals, with different cultural backgrounds, ethnicities, religions, experiences, geographical origins, and family origins. Two visitors will not use the exact same keywords to describe what they are looking for in Google, even if they are looking for the same thing. And two visitors who are looking for entirely different things might use the same keywords. You will never engage perfectly with your diverse Web audience. But if you cover the range of possibilities as completely as you can, you will do a better job of targeting the diverse set of individuals who share an interest in your content.

Another consideration in any content plan is the linking plan. Links are not merely flat pathways from one page to another. Links themselves convey relevance. A key aspect of gaining link equity (or link juice) from internal links is to have clickable text displayed to users that takes them on the next leg of their journey through your site. If the text of a link to a page matches the keywords on the target page, Google will give you the maximum value for that link. So if you design your pages with keywords in mind, you can write your link text to match the keywords of your destination pages.

For these reasons, it’s best to start your content plan with a description of your target audience. Then, perform keyword research into what words and phrases your target audience uses to find similar content. When you do this, you will start to see semantic relationships between the high-demand keywords in the same cloud, so that within your site architecture, you can connect pages based on those keywords. It can also make you more aware of how your target audience uses keywords to find related relevant content.

You can also start to see how to fill gaps in your content plan. As a first pass, you could add high-demand keywords. A second pass might include the keywords in the same clouds as the high-demand keywords. The third pass might include long-tail keywords. You need not get to this level of granularity initially, but the process of developing a content plan from a set of high-demand keywords can go all the way down to the long-tail. The important thing is that keywords can guide you at just about every level of site architecture.

Besides developing the most logical site architecture you can, developing search-optimized site architectures has four main benefits:

- It enables you to cover the range of possible keyword combinations that your target audience uses, thus capturing a higher proportion of targeted visitors.

- It enables you to fill gaps in content that you did not appreciate prior to doing keyword research.

- It enables you to gain market intelligence on your target audience, which helps you better address the needs of the audience that you attract from Google.

- It enhances internal link equity. Search engines use the same algorithm to assess whether two pages are relevant to each other as they do to judge if a page is relevant to a keyword phrase. If the pages that link to one another on your experience have related keywords, Google will judge them as relevant to each other, and that will tend to increase their PageRank from your internal links.

When you build sites based on your target audience’s keyword usage, you ensure that visitors will find the items they need from your grocery store of content. Your pages, or shelves, will be well stocked with all the items that your diverse, but focused, audience needs. And you can minimize empty shelves and reduce redundant page inventory in the process.

Developing a Search-Optimized Information Governance System

So far we’ve helped you optimize a whole architecture of your own pages. But what if your pages are related to others on your site and you don’t own those other pages? How do you collaborate effectively with others in your company who also publish Web content on your site, so that the whole site experience is search optimized?

Perhaps you write for marketing pages and you need to understand content from other parts of the sales cycle, such as support, in order to draw the right audience to your pages. Or perhaps you write for the support organization and you need to collaborate with others in your own organization to ensure that you are all creating an orchestrated content experience for customers who need support. Whatever your role, chances are you have experienced customers coming to your pages from other parts of the site and having trouble with the user experience because that other part of the site does things differently.

One of the main complaints we get at IBM through the “Rate This Page” and “Web Listening Post” Web surveys is that content seems duplicated. If you work on a site with any complexity at all, especially if multiple owners maintain different areas of the site, you will know that it’s extremely difficult to keep duplicate content out of the experience. Unless these various owners from different parts of the site have a collaborative governance system, they end up building parallel experiences and competing with one another for the same audiences. In many cases, they even use the same keywords for their pages, which dilutes the effectiveness of any one page on the same topic.

Your organization doesn’t have to have the size and scope of IBM to experience the difficulties in sharing content—or even information about content—between content owners who share one site. Even a site with five owners (such as a blog by one of this book’s authors, Twinkietown.com) can run into conflicts. The author has written several blog posts, only to be pushed off the front page by collaborators who were unaware of concurrent development. Unless you are the only one responsible for content on your site, chances are that you need a management system that all content owners can access.

Modern content management systems contain content calendar functions, and other features that help Web publishers from different organizations within one company develop content in an orchestrated way. If that describes your current environment, feel free to skip the rest of this section. But if, like IBM, you have multiple content management systems and authoring environments within a large company environment, read on. We have learned some lessons in one of the largest and most complex content management environments in the world. You can put these lessons to use to make your whole Web experience better.

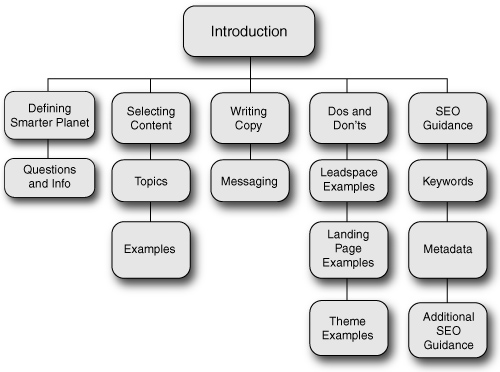

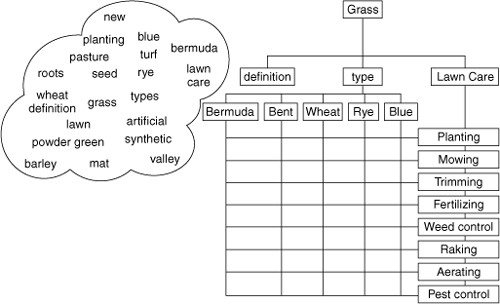

No matter what system you use to govern gaps and overlaps across an enterprise of content with multiple owners, we recommend that you base your underlying structure on keywords. Just as you build a search-optimized site architecture from a set of keyword clouds, so you should base your whole content enterprise on a bank of keyword clouds (see Figure 6.5). Imagine a spreadsheet with the keywords, associated pages, page owners, target audiences, page purposes, related assets, metadata, and other relevant information as the main columns, and individual pages as the rows.

Figure 6.5. Using Quintura, we developed a keyword cloud around the word “Grass.” From that, we made a site map.

If every content owner from a business has such a spreadsheet of current and planned content, everyone can plan and execute content that does not overlap with existing or reserved keywords. Without that information, content owners might create their content as a multitude of unrelated, unconnected sites under one domain. This leads to poor search optimization, and to a failure to connect your target audience with relevant content. So a centralized management system is a must for large enterprise content teams. It all starts with keyword clouds and then proceeds with a content, site architecture and linking strategy. Publishing the content is just the first step. As the multiple related pages on a site evolve, they need a common metrics platform by which to judge how the orchestrated experience is performing as a whole. See Chapter 9 for information on that topic.

Summary

• Pages are not developed in isolation, but in the context of an entire site experience.

• Unlike print information experiences, Web experiences must be flexible and interactive, allowing users to create the experience that best suits their needs.

• Gearing Web pages for your users starts with a clear site architecture, which makes it easy to follow the paths through a site to get to their destination.

• Clear site architecture helps users and search crawlers find what they’re looking for. It also helps improve the PageRank for your pages.

• Clear site architecture is not enough, however. You also need to develop search-optimized site architecture.

• Search-optimized site architecture starts with keyword research to develop a content plan that matches the high-demand search terms that your target audience uses to describe topics related to yours. If necessary, the plan can proceed to the keyword clouds around the high-demand keywords, and, ultimately, to the long-tails. The content plan spawns a flow diagram and, ultimately, wireframes that detail the site experience for the user.

• Developing pages from these wireframes is an iterative process, often resulting in many drafts and revisions.

• After a set of pages is published, tuning the experience for the target audience is also an iterative process involving page effectiveness metrics, page and link changes, republishing, and additional metrics.

• In larger organizations, content owners must work together through a collaborative management system to reduce keyword competition, content overlaps, and confusing interlinking.