Preparing for Your User Research Activity

Introduction

Presumably, you have completed all the research you can before involving your end users (refer to Chapter 2, page 24) and you have now identified the user research activity necessary to answer some of your open questions. In this chapter, we detail the key elements of preparing for your activity. These steps are critical to ensuring that you collect the best data possible from the real users of your product. We cover everything that happens or that you should be aware of prior to collecting your data—from creating a proposal to recruiting your participants.

Creating a Proposal

A proposal is a road map for the activity you are about to undertake. Whether you are a student writing a thesis or dissertation proposal, a nonprofit employee, or a corporate UX researcher, the idea behind creating a proposal is the same: to place a stake in the ground for everyone to work around. Proposals do not need to take long to write but can provide a great deal of value by getting everyone on the same page. In the following sections, we focus primarily on creating a business proposal because academic institutions and the like will have varied specific requirements. However, the general principles apply to all types of proposals.

Why Create a Proposal?

As soon as you and the team decide to conduct a user research activity, you should write a proposal. A proposal benefits both you and the product team by forcing you to think about the activity in its entirety and determining what and who will be involved. You need to have a clear understanding of what will be involved from the very beginning, and you must convey this information to everyone who will have a role in the activity.

A proposal clearly outlines the activity that you will be conducting and the type of data that will be collected. In addition, it assigns responsibilities and sets a time schedule for the activity and all associated deliverables. This is important when preparing for an activity that depends on the participation of multiple people. You want to make sure everyone involved is clear about what they are responsible for and what their deadlines are. A proposal will help you do this. It acts as an informal contract. By specifying the activity that will be run, the users who will participate, and the data that will be collected, there are no surprises, assumptions, or misconceptions.

Sections of the Proposal

There are a number of key elements to include in your proposal. We recommend including the following sections.

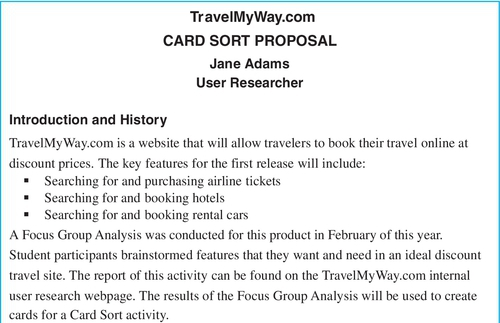

History

The history section of the proposal is used to provide some introductory information about the product and to outline any user research activities that have been conducted in the past for this product. This information can be very useful to anyone who is new to the team.

Objectives, Measures, and Scope of the Study

This section provides a brief description of the activity you will be conducting, as well as its goals, and the specific data that will be collected. It is also a good idea to indicate the specific payoffs that will result from this activity. This information helps to set expectations about the type of data that you will and will not be collecting. Do not assume that everyone is on the same page.

Method

The method section details how you will execute the activity and how the data will be analyzed. Often, members of a product team have never been a part of the kind of activity that you plan to conduct. This section is also a good refresher for those who are familiar with the activity but may not have been involved in this type of activity recently.

User Profile (aka “Participants”)

In this section, detail exactly who will be participating in the activity. It is essential to document this information to avoid any misunderstandings later on. You want to be as specific as possible. For example, do not just say “students;” instead, state exactly the type of student you are looking for. This might be the following:

■ Between the ages of 18 and 25

■ Currently enrolled in an undergraduate program

■ Has experience booking vacations on the web

It is critical that you bring in the correct user type for your activity. Work with the team to develop a detailed user profile (refer to Chapter 2, “User Profile” section, page 37). If you have not yet met with the team to determine the user profile, be sure to indicate that you will be working with them to establish the key characteristics of the participants for the activity. Avoid including any “special users” that the team thinks would be “interesting” to include but are outside of the user profile.

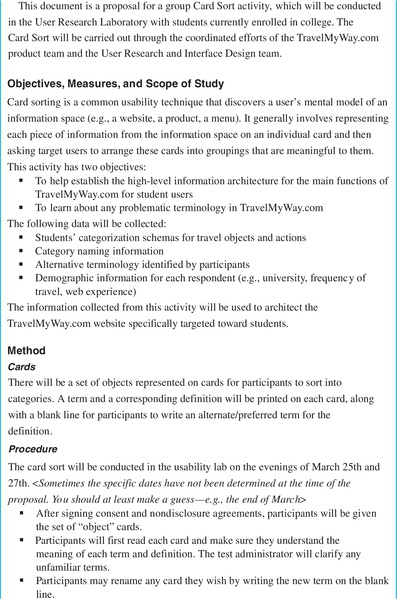

Recruitment

In this section, describe by whom and how the participants will be recruited. Will you recruit them, or will the product team do this? Will you post an advertisement on the web, use social media, or use a recruitment agency? Will you contact current customers? How many people will you recruit?

You will need to provide answers to all of these questions in the recruitment section. If the screener for the activity has already been created, you should attach this to the proposal as an appendix (see “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 129).

Incentives

Specify how participants will be compensated for their time and how much they will be compensated (see “Determining Participant Incentives” section, page 127). Also, indicate who will be responsible for acquiring these incentives. If the product team is doing the recruiting, you want to be sure the team does not offer inappropriately high incentives to secure participation (refer to Chapter 3, “Appropriate Incentives” section on page 73 for a discussion of appropriate incentive use). If your budget is limited, you and the product team may need to be creative when identifying an appropriate incentive.

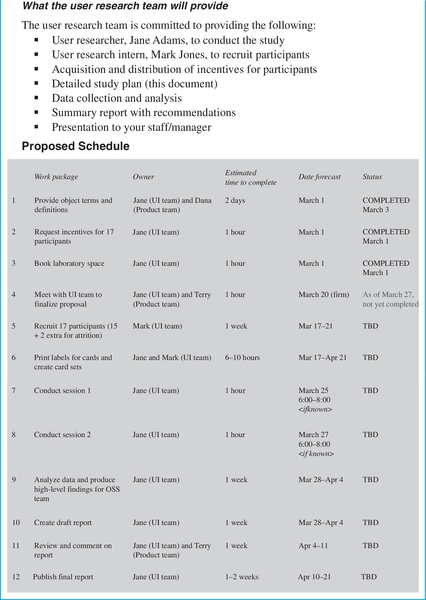

Responsibilities and Proposed Schedule

This is one of the most important pieces of your proposal—it is where you assign roles and responsibilities, as well as deliverable dates. Be as specific as possible in this section. Ideally, you want to have a specific person named for each deliverable. For example, do not just say that the product team is responsible for recruiting participants; instead, state that “John Brown from the product team” is responsible. The goal is for everyone to read your proposal and understand exactly who is responsible for what.

The same applies to dates—be specific. You can always amend your dates if timing must be adjusted. It is also nice to indicate approximately how much time it will take to complete each deliverable. If someone has never before participated in one of these activities, he or she might assume that a deliverable takes more or less time than it really does. People most often underestimate the amount of time it takes to prepare for an activity. Sharing time estimates in your proposal can help people set their own deadlines. In some cases, you may even want to include hours and cost. For example, if you are a consultant or your team uses a charge back model to other groups within the company, this level of detail will be important.

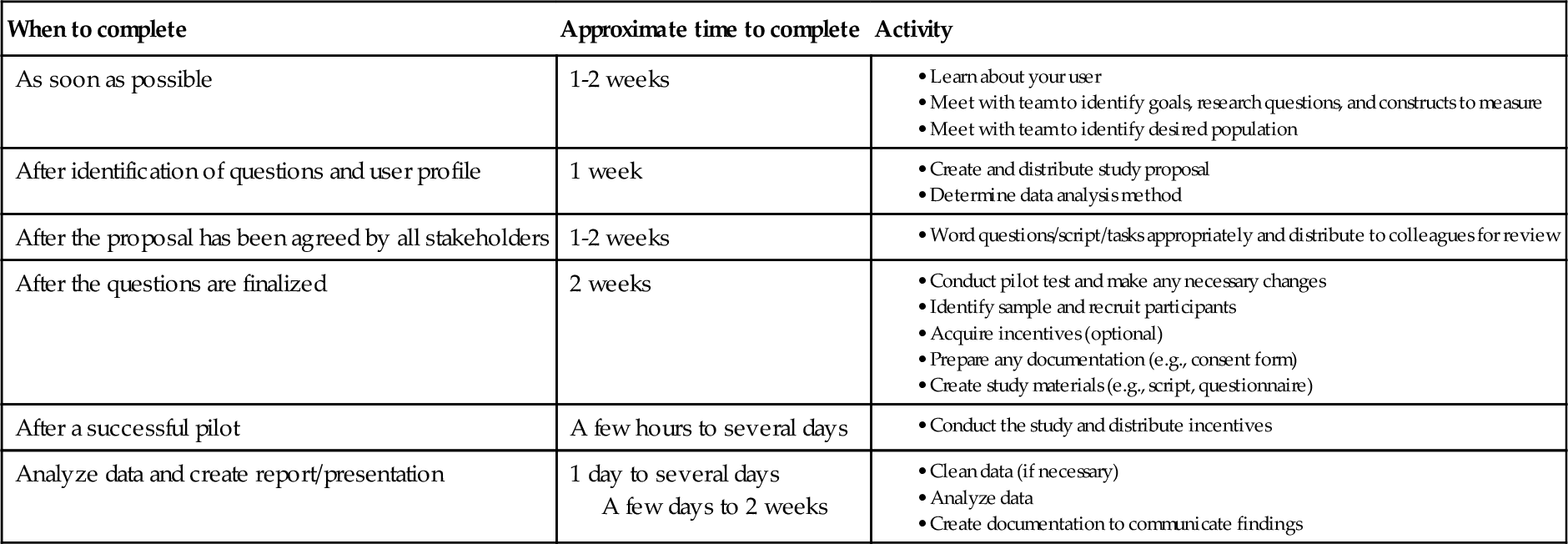

Once the preparation for the activity is under way, you can use this chart to track the completion of the deliverables. You will be able to see at a glance what work is outstanding and who is causing the bottleneck. In the next section, we provide a guide to help you determine how much time to plan for each phase of preparation.

Preparation Timeline

Table 6.1 contains approximate times based on our personal experience and should be used only as a guide. If you are new to research, the length estimate will likely be much longer. For example, it may take you double the time to create the questions, conduct the study, and analyze the data. In addition, the length of time for each step depends on a variety of factors, such as responsiveness of the product team, access to users, and resources available.

Table 6.1

Preparation timeline

Sample Proposal

The best way to get a sense of what a proposal should contain and the level of detail is to look at an example. Figure 6.1 offers a sample proposal for a card sorting activity to be conducted for our fictitious travel app. This sample can be easily modified to meet the needs of any activity.

Getting Commitment

Your proposal is written, but you are not done yet. In our experience, if stakeholders are unhappy with the results of a study, they will sometimes criticize one (or more) of the following:

■ The skills/knowledge/objectivity of the person who conducted the activity

■ The participants in the activity

■ The tasks/activity conducted

Being a member of the team and earning their respect (refer to Chapter 1, “Preventing Resistance” section, page 19) will help with the first issue. Getting everyone to sign off on the proposal can help with the last two. Make sure that everyone is clear, before the activity, about all aspects of the study to avoid argument and debate when you are presenting the results. This is critical. If there are objections or problems with what you have proposed, it is best to identify and deal with them now.

You might think that all you have to do is send the proposal to the appropriate people. This is exactly what you do not want to do! Never e-mail your proposal to all the stakeholders and assume they read it. In some cases, your e-mail will not even be opened. The reality is that everyone is very busy and most people do not have the time to read things that they do not believe to be critical. People may not believe your proposal is critical. It is your job to help them understand that it is.

Instead, organize a meeting to review the proposal. It can take as little as 30 minutes to review the proposal as a group. Anyone involved in the preparation for the activity or who will use the data should be present. At this meeting, you do not need to go through every single line of the proposal in detail, but you do want to hit several key points. They include the following:

■ The objective of the activity. It is important to have a clear objective and to stick to it. Often in planning, developers will bring up issues that are out of the scope of the objective. Discussing it up front can keep the subsequent discussions focused.

■ The data you will be collecting. Make sure the team has a clear understanding of what they will be getting.

■ The users who will be participating. You really want to make this clear. Make sure everyone agrees that the user profile is correct. You do not want to be told after the activity has been conducted that the users “were not representative of the product’s true end users”—and hence, the data you collected are useless. It may sound surprising, but this is not uncommon.

■ Each person’s role and what he or she is responsible for. Ensure that everyone takes ownership of roles and responsibilities. Make sure they truly understand what they are responsible for and how the project schedule will be impacted if delivery dates are not met.

■ The timeline and dates for deliverables. Emphasize that it is critical for all dates to be met. In many cases, there is no opportunity for slipping.

Although it may seem overkill to schedule yet another meeting, meeting in person has many advantages. First of all, it gets everyone involved, rather than creating an “us” versus “them” mentality (refer to Chapter 1, “Preventing Resistance” section, page 19). You want everyone to feel like a team going into this activity. In addition, by meeting, you can make sure everyone is in agreement with what you have proposed. If they are not, you now have a chance to make any necessary adjustments and all stakeholders will be aware of the changes. At the end of the meeting, everyone should have a clear understanding of what has been proposed and be satisfied with the proposal. All misconceptions or assumptions should be removed. Essentially, your contract has been “signed.” You are off to a great start.

Deciding the Duration and Timing of Your Session

You will need to decide the duration and timing of your session(s) before you begin recruiting your participants. It may sound like a trivial topic, but the timing of your activity can determine the ease or difficulty of the recruiting process; it may be easier to recruit people for an hour block after work hours than an hour block during regular work hours, for example. For individual activities, we offer users a variety of times of day to participate, from early morning to around 8 pm. We try to be as flexible as possible and conform to the individual’s schedule and preference. This flexibility allows us to recruit more participants.

For group sessions, it is a bit more challenging because you have to find one time to suit all participants. The participants we recruit typically have daytime jobs from 9 am to 5 pm, and not everyone can get time off in the middle of the day. We have found that conducting group sessions from 5-7 pm and 6-8 pm work best. We like to have our sessions end by 8 pm or 8:30 pm, as we have found that, after this time, people get very tired and their productivity drops noticeably. Because most people usually eat dinner around this time, we have discovered that providing dinner shortly before the session makes a huge difference. Participants appreciate the thought and enjoy the free food, and their blood sugar is raised so they are thinking better and have more energy. As an added bonus, participants chat together over dinner right before the session and develop a rapport. This is valuable because you want people to be comfortable in sharing their thoughts and experiences with each other. The cost is minimal (about $60 for two large pizzas, soda, and cookies), and it is truly worth it. For individual activities that are conducted over lunch or dinnertime, you may wish to do the same. The optimal times will depend on the working hours of your user type. If you are trying to recruit users who work night shifts, these recommended times may not apply.

User research activities can be tiring for both the moderator and the participant. They demand a good deal of cognitive energy, discussion, and active listening to collect effective data. We have found that two hours is typically the maximum amount of time you want to keep participants for most user research activities. This is particularly the case if the participants are coming to your activity after they have already had a full day’s work. Even two hours is a long time, so you want to provide a break when you see participants getting tired or restless. If you need more than two hours to collect data, it is often advisable to break the session into smaller chunks and run it over several days or evenings. For some activities, such as surveys, two hours is typically much more time than you can expect participants to provide. Keep your participants’ fatigue rate in mind when you decide how long your activity will be.

Recruiting Participants

Recruitment can be a time-consuming and costly activity. The information in this section can help you recruit users who represent the population of interest and can save you time, money, and effort.

Determining Participant Incentives

Before you can begin recruiting participants, you need to identify how you will compensate people for taking time out of their day to provide you with their expertise. You should provide your participants with some kind of incentive to thank them for their time and effort. The reality is that it also helps when recruiting, but you do not want your incentive to be the sole reason why people are participating. You should not make the potential participants “an offer they cannot refuse” (refer to Chapter 3, “Appropriate Incentives” section, page 73).

We are often asked, “How much should I pay?” Based on our experiences and discussions with academics and professionals, incentive amounts can vary from $25 to $125 per hour based on many factors, including budget, location, user type, length of study, complexity of study, and more. We cannot provide strict guidance about how large an incentive you should offer. In the San Francisco Bay Area, we typically pay $100 per hour, whereas in Clemson, South Carolina, we typically pay participants $10-20 per hour. We may vary incentives based on the user type as well; for example, we may pay orderlies $50 for a two-hour study, but pay physicians $200 for the same session.

We recommend that you speak with colleagues at organizations similar to yours to see what the norm is. Offering too little can result in no participation for your studies. However, offering large incentives may encourage dishonest individuals to participate in your study. They may not be truthful about their skills. Make the incentive large enough to thank people for their time and expertise but nothing more.

Generic Users

When we use the term “generic users,” we are referring to people who participate in a user research activity, but have no ties to your company, university, or nonprofit organization. They are not customers or employees of your company or organization. They have typically been recruited via an advertisement or an internal database of potential participants, and they are representing themselves, not their company, at your session (this is discussed further in “Recruitment Methods”). This is the easiest group to compensate because there is no potential for conflicts of interest. You can offer them whatever you feel is appropriate. Some standard incentives include:

■ One of your company products for free (e.g., a piece of software)

■ A gift card (e.g., to an electronics store, to a department store) or a movie pass

■ Charitable donations in the participant’s name

Cash is often very desirable to participants, but it can be difficult to manage if you are running a large number of studies with many participants. In our experience, we have found a gift card to be a great alternative to cash. Gift cards can be used like a credit card. Participants can spend them at any place that takes credit cards, and they are convenient to manage. One thing to be aware of is that some gift cards charge convenience fees. You have to choose a card that does not have these charges. Or you can opt for an e-certificate for a specific store with a wide variety of options, like Amazon, as they typically do not have fees.

One thing to keep in mind is that you want to pay everyone involved in the same session the same amount. We sometimes come across situations where it is easy to schedule the first few participants but difficult to schedule the last few. Sometimes we are forced to increase the compensation in order to entice additional users. If you find yourself in such a situation, remember that you must also increase the compensation for those you have already recruited. A group session can become very uncomfortable and potentially confrontational if, during the activity, someone casually says, “This is a great way to make $100” to someone who you offered a payment of only $75. You do not want to lose the trust of your participants and potential end users—that is not worth the extra $25.

For highly paid individuals (e.g., CEOs), you could never offer them an incentive close to their normal compensation. For one study, a recruiting agency offered CEOs $500 per hour, but they could not get any takers. In these cases, a charitable donation in their name sometimes works better. For children, a gift card to a toy store or the movies or a pizza parlor tends to go over well (just make sure you approve it with their parents first).

Customers or Your Own Company Employees

If you are using someone within your company as a participant, you may not be able to pay them as you would a generic end user. We often use company logo gear, or “swag,” for these kinds of participants as a token of thanks. This is also often the case in corporate accounts with business users. Paying customers could represent a conflict of interest because this could be perceived as a payoff. Additionally, most activities are conducted during business hours, so the reality is that their company is paying for them to be there. The same is true for employees at your own company. Thank customer participants or internal employees with a company logo item of nominal value (e.g., mug, sweatshirt, keychain).

If sales representatives or members of the product team are doing the recruiting for you, make sure they understand what incentive you are offering to customers and why it is a conflict of interest to pay customers for their time and opinions. We recently had an uncomfortable situation in which the product team was recruiting for one of our activities. They contacted a customer that had participated in our activities before and always received swag. When the product team told them their employees would receive $150, they were thrilled. When we had to inform the customer that this was not true and that they would receive only swag, they were quite offended. No matter what we said, we could not make the customer (or the product team representative) understand the issue of conflict of interest, and they continued to demand the payment. After we made it clear that this would not happen, they declined to participate in the activity. You never want the situation to get to this point.

Students

In some academic settings, students are encouraged to participate in research activities as a way to learn about the research process. Sometimes called a “participant pool,” this group of students may be available to participate in user research studies as part of credit for a course or for extra credit. Ethically, whenever students are offered this opportunity, an alternative such as a writing assignment must be offered so students are not coerced to participate in studies to get extra credit.

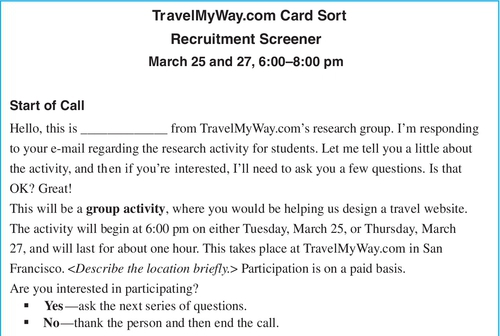

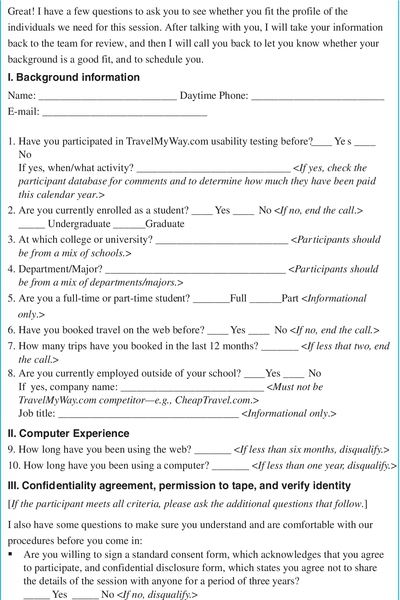

Developing a Recruiting Screener

Assuming you have created a user profile (refer to Chapter 2, “User Profile” section, page 37), the first step in recruiting is to create a detailed phone screener. A screener is composed of a series of questions to help you recruit participants who match your user profile for the proposed activity.

Screener Tips

There are a number of things to keep in mind when creating a phone screener. They include the following:

■ Work with the product team

■ Keep it short

■ Use test questions

■ Request demographic information

■ Eliminate competitors

■ Provide important details

■ Prepare a response for people who do not match the profile

Avoid Screening via E-mail

With the exception of surveys, it is ideal for you to talk to participants before scheduling their session for a number of reasons. Firstly, you want to get a sense of whether or not they truly match your profile, and it is difficult to do this via e-mail. Secondly, you want to make sure the participants are clear about what the activity entails and what they will be required to do (see “Provide Important Details” section, page 131). However, this may not always be practical. If you cannot speak with potential participants, we recommend a questionnaire like Google Forms, rather than e-mail. It is much easier to see at a glance in one spreadsheet who qualifies and who does not. The questionnaire is also an easy way to ensure you get the information you need consistently.

Work with the Product Team

We cannot emphasize too strongly how important it is to make sure you and the team are aligned on who the right users are for this study. Your screener is the tool to help with this. Make sure the product team helps you develop it. Their involvement will also help instill the sense that you are a team working together, and it will avoid anyone from the product team saying “You brought in the wrong user” after the activity has been completed.

Keep It Short

In the majority of cases, a screener should be relatively short. You do not want to keep a potential participant on the phone for more than 10 minutes. People are busy, and they do not have a lot of time to chat with you. You need to respect their time. Also, you are very busy and the longer your screener is, the longer it will take you to recruit your participants.

© 2000 The New Yorker Collection 2000 J. B. Handelsman from cartoonbank.com. All rights reserved.

Use Test Questions

Make sure that your participants are being honest about their experience. We are not trying to say that people will blatantly lie to you (although occasionally they will), but sometimes, people may exaggerate their experience level, or they may be unaware of the limitations of their knowledge or experience (thinking they are qualified for your activity when, in reality, they are not).

When recruiting technical users, determine that they have the correct level of technical expertise. You can do this by asking test questions. This is known as knowledge-based screening. For example, if you are looking for people with moderate experience with HTML coding, you might want to ask “What is a Common Gateway Interface (CGI) script and how have you used it in the past?” Like other user research activities, creating a good test question will require you to know the domain well.

Request Demographic Information

Your screener can also contain some further questions to learn more about the participant. These questions typically come at the end, once you have determined that the person is a suitable candidate. For example, you might want to know the person’s age and gender. Depending on your study needs, this information may be used to exclude them from participation. For example, if you are studying a new input device on a mobile phone among older adults, you will not include younger participants in your research activities. You can also use this demographic information to balance the diversity of your population of participants. In some academic situations, you are not able to collect this information until the time of the study. Be sure you know your policies in this area.

Eliminate Competitors

If you work for a company, always, always find out where the potential participants work before you recruit them. You do not want to invite employees from companies that develop competing products (i.e., companies that develop or sell products that are anywhere close to the one being discussed in the study). Assuming you have done your homework (refer to Chapter 2, page 24), you should know who these companies are. Similarly, depending on your circumstances, you want to avoid members of the press, regardless of whether they will sign a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) or not. You might imagine that, ethically and legally, this would never happen, but it does. We once had a situation where an intern recruited someone from a competitor to participate in an activity; as luck would have it, the participant cancelled later on. If you find out that you have recruited a competitor before the study begins, call the participant and explain that you must cancel. Apologize for any inconvenience but state that you must cancel the appointment. People will usually understand.

Sending the participants’ profiles to the product team after recruitment is also a good double-check. The team may recognize a competitor they forgot to tell you about. If you are in doubt about a company, a quick web search can usually reveal whether the company in question makes products similar to yours.

Provide Important Details

Once you have determined that a participant is a good match for the activity, you should provide the person with some important details. It is only fair to let the potential participants know what they are signing up for (refer to Chapter 3, to learn more about how to treat participants). You do not want there to be any surprises when they show up on the day of the activity. Your goal is not to trick people into participating, so be up front. You want people who are genuinely interested. Here are some examples of things you should discuss:

■ Logistics: Time, date, and location of the activity.

■ Incentives: Tell them exactly how and how much they will be compensated.

■ Group versus individual: Let them know whether it is a group or individual activity. Some people are painfully shy and do not work well in groups. It is far better for you to find out over the phone than during the session. We have actually had a couple of potential participants who declined to participate in a session once they found out it was a group activity. They simply did not feel comfortable talking in front of strangers. Luckily, we learned this during the phone interview and not during the session, so we were able to recruit replacements. Conversely, some people do not like to participate in individual activities because they feel awkward going in alone.

■ Recording: Tell people in advance if you plan to record the session. Some people are not comfortable with this and would rather not participate. Others will want to make sure they dress well, look nice, etc.

■ Appointment time: Emphasize that participants must be on time. Late participants will not be introduced into an activity that has already started (refer to Chapter 7, “The Late Participant” section, page 176).

■ ID: If your company requires an ID from participants before entry, inform them that they will be required to show an ID before being admitted into the session (see “The Professional Participant” section, page 151).

■ Legal forms: Inform them that they will be required to sign a consent and NDA, if applicable, and make sure that they understand what these forms are (refer to Chapter 3, “Legal Considerations” section, page 76). You may even want to fax the forms to the participants in advance.

Prepare a Response for People Who Do Not Match the Profile

The reality is that not everyone is going to match your profile, so you will need to reject some very eager and interested potential participants. Before you start calling, you should have a response in mind for the person who does not match the profile. It can be an uncomfortable moment, so have something polite in mind to say, and include this in your screener so you do not find yourself lost for words. We often say, “I’m sorry, you do not fit the profile for this particular study, but thank you so much for your time.” If the person seems to be a great potential candidate, encourage him or her to respond to your recruitment postings in the future.

Sample Screener

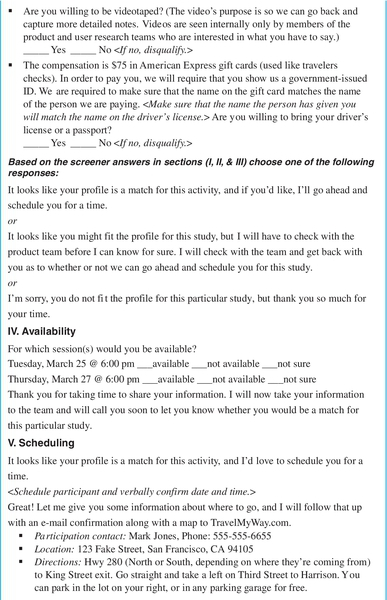

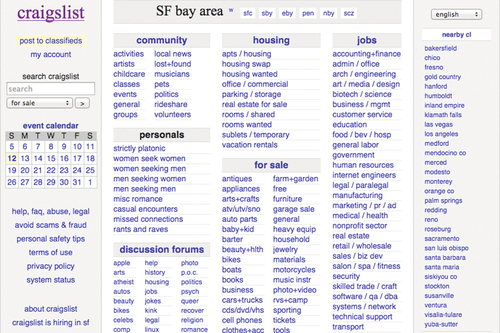

Figure 6.2 is a sample screener for the recruitment of students for a group card sorting activity. This should give you a sense of the kind of information that is important to include when recruiting participants.

Creating a Recruitment Advertisement

Regardless of the method you choose to recruit your participants, whether it is via social media, a web posting, or an internal database of participants (discussed later in “Recruitment Methods”), you will almost always require an advertisement to attract appropriate end users. Depending on your method of recruiting, you or the recruiter may e-mail the advertisement, post it on a website or social media, or relay its message via the phone. Potential participants will respond to this advertisement or posting if they are interested in your activity. You will then reply to these potential participants and screen them.

There are several things to keep in mind when creating your posting.

Provide Details

Provide some details about your study. If you simply state that you are looking for users to participate in a user research study, you will be swamped with responses! This is not going to help you. In your ad, you want to provide some details to help narrow your responses to ideal candidates, for example, seeking HTML5 experts between the ages of 45 and 65 years.

Include Logistics

Indicate the date, time, and location of the study. That way, those who are not available will not respond. You want to weed out unavailable participants immediately.

Cover Key Characteristics

Indicate some of the key characteristics of your user profile. This will prescreen appropriate candidates. These are usually high-level characteristics (e.g., job title, company size). You do not want to reveal all of the characteristics of your profile because, unfortunately, there are some people who will pretend to match the profile. If you list all of the screening criteria, deceitful participants will know how they should respond to all of your questions when you call.

For example, let us say you are looking for people who:

■ Have purchased at least three airline tickets via the web within the last 12 months

■ Have booked at least two hotels via the web within the last 12 months

■ Have booked at least one rental car via the web within the last 12 months

■ Have experienced using the http://www.TravelMyWay.com website or app

■ Have a minimum of two years’ web experience

■ Have a minimum of one year computer experience

In your posting, you might indicate that you are looking for people who are over 18, enjoy frequent travel, and have used travel apps.

Do Not Stress the Incentive

Avoid phrases like “Earn money now!” This attracts people who want easy money and those who will be more likely to deceive you for the cash. Incentives are meant to compensate people for their time and effort, as well as to thank them, not entice them to do something they otherwise would hesitate to do. An individual who is attending your session only for the money will complete your activity as quickly as possible and with as little effort as possible. That kind of data can do more harm than good. Trust us.

State How They Should Respond

We suggest providing a generic, single-purpose e-mail address (e.g., [email protected]) for interested individuals to respond to rather than your personal e-mail address or phone number. If you provide your personal contact information (particularly a phone number), your voice mail and/or e-mail inbox will be jammed with responses. Another infrequent but possible consequence is being contacted by desperate individuals wanting to participate and wondering why you have not called them yet. By providing a generic e-mail address, you can review the responses and contact whomever you feel will be most appropriate for your activity.

It is also nice to set up an automatic response on the e-mail account, if it is used solely for recruiting purposes. Keep it generic, so you can use it for all of your studies. Here is a sample response:

Thank you for your interest in our study! We will be reviewing interested respondents over the next two weeks, and we will contact you if we think you are a match for our study.

Sincerely,

TheTravelMyWay.comTeam

Include a Link to Your In-House Participant Database

If you have an in-house participant database (see below to learn more), you should point participants to your web questionnaire, at the bottom of your ad.

Be Aware of Types of Bias

Ideally, you do not want your advertisement to appeal to certain members of your user population and not others. You do not want to exclude true end users from participating. This is easy to do unknowingly based on where you post your advertisement or the content within the advertisement.

For example, let us say that http://www.TravelMyWay.com is conducting a focus group for frequent travelers. To advertise the activity, you have decided to post signs around local colleges and on college webpages because students are often looking for ways to make easy money. As a result, you have unknowingly biased your sample to people who are in these college buildings (i.e., mostly students), and it is possible that any uniqueness in this segment of the population may impact your results. Make sure you think about bias factors when you are creating and posting your advertisement.

Another type of bias is referred to as nonresponder bias. This is created when certain types of people do not respond to your posting. There will always be suitable people who do not respond, but if there is a pattern, then this is a problem. To avoid nonresponder bias, you must ensure that your call for participation is perceived equally by all potential users and that your advertisement is viewed by a variety of people from within your user population.

One kind of bias that you are unable to eliminate is self-selection bias. You can reduce this by inviting a random sample of people to complete your survey (i.e., a survey pop-up appears for every 10th visitor who comes to your website), rather than having it open to the public, but the reality is that not all people you invite will want to participate. Some of the invited participants will self-select to not participate in your activity.

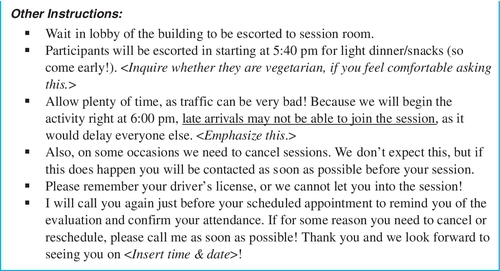

Sample Posting

Figure 6.3 is a sample posting to give you a sense of how a posting might look when it all comes together.

Recruitment Methods

There are a variety of methods to attract users, and each method has its own strengths and weaknesses. If one fails, then you can try another. In this section, we will touch on some of these methods, so you can identify the one that will best suit your needs.

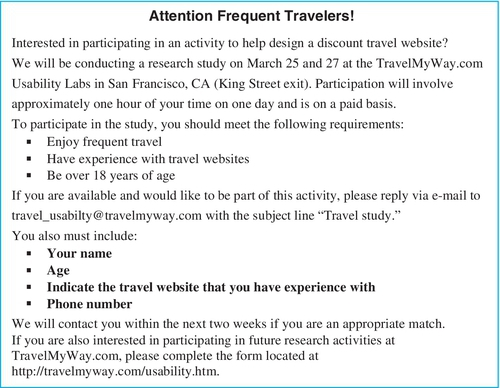

Advertise on Community Bulletin Board Sites and Via Social Networks

Web-based community bulletin boards (e.g., http://www.craigslist.org) allow people to browse everything from houses to jobs to things for sale (see Figure 6.4). We have found them to be an effective way to attract a variety of users. We will typically place these ads in the classified section under “Jobs.” You may be able to post for free or for less than $100, depending on the area of the country you live in and the particular bulletin board. The ad is usually posted within 30 minutes from when you submit it. One of the advantages of this method is that it is a great prescreen if you are looking for people who use the web and/or computers. If they have found your ad, you know they are web users! However, you should be aware that this has become such a popular source for study recruitment, particularly in tech areas like the San Francisco Bay Area, Seattle, New York, Atlanta, and Austin, that “professional” participants lurk on those sites. These are individuals that spend a significant portion of their time participating in studies and may not be completely honest in screeners so they can increase their chances of being selected.

If you are looking for people who are local, use a site that is local to your area. Sites such as your local newspaper website or community publications are good choices. If you do not have access to any web publications in your area or if you want people who do not have web experience, you could post your advertisement in a physical newspaper or even on paper on real bulletin boards.

Create an In-House Database

You can create a database within your organization where you maintain a list of people who are interested in participating in user research activities. This database can hold some of the key characteristics about each person (e.g., age, gender, job title, years of experience, industry, company name, location, etc.). Prior to conducting an activity, you can search the database to find a set of potential participants who fit your user profile.

Once you have found potential participants, you can e-mail them some of the information about the study and ask them to e-mail you if they would like to participate. The e-mail should be similar to an ad you would post on a web community bulletin board site (see Figure 6.3). State that you obtained the person’s name from your in-house participant database, which he or she signed up for, and provide a link or option to be removed from your database. For those who respond, you should then contact them over the phone and run through your screener to check that they do indeed qualify for your study (refer to “Developing a Recruiting Screener” section, page 129).

Social media is a great mechanism for getting people to sign up and take your database survey. We use sites like Google +, Facebook, and Twitter. Today, most companies have official pages on all three, both as just the company (e.g., http://www.google.com) and as product-specific pages (e.g., Chrome). So if you need to attract a particular product user, it is very helpful to post on those product pages. It helps with legitimacy, and we really do see a spike in sign-ups when we do it. We do not recommend social media for individual studies, though, because people will post questions like “Was I selected?” “When will I find out?” “Why wasn’t I selected?” With hundreds of sign-ups, there is no way we could respond to everyone about a single study.

Use a Recruiting Agency

You can hire companies to do the recruiting for you. They have staff devoted to finding participants. These companies are often market research firms, but depending on your user type, temporary staffing agencies can also do the work. You can contact the American Marketing Association (www.marketingpower.com) to find companies that offer this service in your area. It can certainly be extremely helpful. We have found that a recruiting service is most beneficial when trying to recruit a user type that is difficult to find. They are also great when you need to conduct a brand-blind and/or sponsor-blind study (i.e., when you do not want participants to know who is conducting the study or for whom the product was created).

For example, we needed to conduct a study with physicians. Our participant database did not contain physicians, and an electronic community bulletin board posting was unsuccessful. As a result, we went to a recruiting agency and they were able to get these participants for us.

An additional benefit to using recruiting agencies is that they usually handle the incentives. Once you have a purchase order with the company, you can include money for incentives. The recruiting agency will then be responsible for paying the participants at the end of a study. This is one less thing for you to worry about.

You might ask, “Why not use these agencies exclusively and save time?” One of the reasons is cost. Typically, they will charge anywhere from $100 to $200 to recruit each participant (not including the incentives). The price varies depending on how hard they think it will be for them to attract the type of user you are looking for. If you are a little more budget-conscious, you might want to pursue some of the other recruiting options, but keep in mind that your time is money. A recruiting agency might be a bargain compared to your own time spent recruiting.

Also, in our experience, participants recruited by an agency have a higher no-show rate and are more likely to be professional participants. One reason for this is that not all agencies call to remind the participants about the activity the day before (or on the day of) the study. Additionally, using a recruiting agency adds a level of separation between you and the participants—if you do the recruiting yourself, they may feel more obligated to show up. Your experience will vary depending on the vendor and your specific needs, so do your homework!

Some recruiting agencies need more advance notice to recruit than we normally need ourselves. Some agencies we have worked with required a one-month notice to recruit so they had enough resources lined up. The smaller the agency, the more likely this will be the case. Consequently, if you need to do a quick, lightweight activity, an agency might not be able to assist you, but it never hurts to inquire.

Lastly, we have found that agencies are not effective in recruiting very specialized user types. Typically, the people making the calls will not have domain knowledge about the product you are recruiting for. Imagine you are conducting a database study and you require participants who have an intermediate level of computer programming knowledge. You have devised a set of test questions to assess their knowledge about programming. Unless these questions have very precise answers (e.g., multiple-choice), the recruiter will not be able to assess whether the potential participant is providing the correct answers. A participant may provide an answer that is close enough, but the recruiter does not know that. Even having precise multiple-choice answers does not always help. Sometimes, the qualifications are so complex that you simply have to get on the phone with candidates.

Regardless of these issues, a recruiting agency can be extremely valuable. If you decide to use one, there are a few things to keep in mind.

Cartoon by Abi Jones

Provide a Screener

You will still need to design the phone screener and have the product team approve it (see above to learn more). The recruitment agency will know nothing about your product, so the screener may need to be more detailed than usual. Indicate what the desired responses are for each question and when the phone call should end because the potential participant does not meet the necessary criteria. Also provide a posting, if they are going to advertise to attract participants.

Be sure to discuss the phone screener with the recruiter(s). Do not just send it via e-mail and tell them to contact you if they have any questions. You want to make sure they understand and interpret each and every question as it was intended. Make sure you do this, even if you are recruiting for users with a non-technical profile. You may even choose to do some role-playing with the recruiter. Only when the recruiter begins putting your screener to work will you see whether he or she really understands it. Many research firms will employ a number of people to make recruitment calls. If you are unable to speak with all of them, then you should speak with your key point of contact at the agency and go through the screener.

Ask for the Completed Screeners to Be Sent After Each Person Is Recruited

This is a way for you to monitor who is being recruited and to double-check that the right people are being signed up. You can also send the completed screeners along to members of the product team to make sure they are happy with each recruit. This has been very successful for us in the past.

Ensure They Remind the Participants of Your Activity

It sounds obvious, but reminding participants of your activity will drastically decrease the no-show rate, as will sending them a calendar invite when you schedule them. Sometimes, recruiting agencies recruit participants one to two weeks before the activity. You want to make sure they call to remind people on the day before (and possibly again on the day of) the activity to get confirmation of attendance. It is valuable to include reminder calls in your contract with the recruitment agency, which also states that you will not pay for no-shows. This increases their motivation to get those participants in your door.

Avoid the Professional Participant

Yes, even with recruitment agencies, you must avoid the “professional participant.” A recruitment agency may call on the same people over and over to participate in a variety of studies. The participant may be new to you but could have participated in three other studies this month. Although the participant may meet all of your other criteria, someone who seeks out research studies for regular income is not representative of your true end user. They will likely behave differently and provide more “polished” responses if they think they know what you are looking for.

You can insist that the recruitment agency provide only “fresh” participants. To double-check this, chatting with participants at the beginning of your session can reveal a great deal. Simply ask, “So, how many of you have participated in studies for the ABC agency before?” People will often be proud to inform you that the recruiting agency calls on them for their expertise “all the time.”

Keep in Mind that You Cannot Add Them to Your Database

You may be thinking that you will use a recruiting agency to help you recruit people initially and then add those folks to your participant database for future studies. In nearly all cases, you will not be able to do this. Most recruiting agencies have a clause in their contract that states that you cannot enlist any of the participants they have recruited unless it is done via them. Make sure you are aware of this clause, if it exists.

Make Use of Customer Contacts

Current or potential customers can make ideal participants. They truly have something at stake because, at the end of the day, they are going to have to use the product. As a result, they will likely not have problems being honest with you. Sometimes, they are brutally honest.

Typically, a product team, a sales consultant, or account manager will have a number of customer contacts with whom they have close relationships. The challenge can be convincing them to let you have access to them. Often, they are worried or concerned that you may cause them to lose a deal or that you might upset the customer. Normally, a discussion about your motives can help alleviate this problem.

Start by setting up a meeting to discuss your proposal (see “Getting Commitment” section, page 124). Once the product team member, sales consultant, or account manager understands the goal of your user research activity, they will hopefully also see the benefits of customer participation. It is a “win-win” situation for both you and the customer. Customers love to be involved in the process and have their voices heard, and you can collect some really great data. Another nice perk is that it can cost you less, as you typically provide only a small token of appreciation rather than money (see “Determining Participant Incentives” section, page 127).

Despite your efforts, it is possible that you will be forbidden from talking with certain customers. You will have to live with this. The last thing you want is to make an account manager angry or cause a situation in which a customer calls your company’s representative to complain that he or she wants what the user research group showed him or her, not what the representative is selling. The internal contacts within your company can be invaluable when it comes to recruiting customers—they know their customers and can assist your recruiting—but they have to be treated with respect and kept informed about what you are doing.

If you decide to work with customers, there are several things to keep in mind.

Be Wary of the Angry Customer

When choosing customers to work with, it is best to choose those who currently have a good relationship with your company. This will simply make things easier. You want to avoid situations that involve heavy politics and angry customers. The last thing you or your group needs is to be blamed for a spoiled business deal. However, deals have actually been saved as a result of intervention from the user research professionals—the customer appreciated the attention he or she was receiving and recognized that the company was trying to improve the product based on his or her feedback. If you find yourself dealing with a dissatisfied customer, give the participants an opportunity to vent; however, do not allow this to be the focus of your activity. Providing 15 minutes at the beginning of a session for a participant to express his or her likes, dislikes, challenges, and concerns can allow you to move on and focus on the desired research activity you planned.

When recruiting customers, if you get a sense that the customer may have an agenda, plan a method to deal with this. Customers often have gripes about the current product and want to tell someone. One way to handle this is to have them meet with a member of the product team in a separate meeting from the activity. The user research needs to coordinate this with the product team. It requires additional effort, but it helps both sides.

Avoid the Unique Customer

It is best to work with a customer that is in line with most of your other customers. Sometimes, there are customers who have highly customized your product for their unique needs. Some companies have business processes that differ from the norm or industry standards. If you are helping the product development team conduct user research for a “special customer,” this is fine. If you are trying to conduct user research that is going to be representative of the majority of your user population, you will not want to work with a customer that has processes different from the majority of potential users.

Recruiting Internal Employees

Sometimes, your customers are people who are internal to your company. These can be the hardest people of all to recruit. In our experience, they are very busy and may not feel it is worth their time to volunteer. If you are attempting to recruit internal participants, we have found it extremely effective to get their management’s buy-in first. That way, when you contact them, you can say, “Hi John, I am contacting you because your boss, Sue, thought you would be an ideal candidate for this study.” If their boss wants them to participate, they are unlikely to decline.

Allow More Time to Recruit

Unfortunately, this is one of the disadvantages of using customers. Typically, customer recruiting can be a slow process. There is often corporate red tape that you need to go through. You may need to explain to a number of people what you are doing and whom you need to participate. You also need to rely on someone within the company to help you get access to the right people. The reality is that although this may be your top priority, in most cases, it is not theirs, so things will always move more slowly than you would like. You may also have to go through the legal department for both your company and the customer’s in order to get approval for your activity. NDAs may need to be changed (refer to Chapter 3, “Legal Considerations” section, page 76).

Make Sure the Right People Are Recruited

You need to ensure that your internal recruiter or recruiting agency contact is crystal clear about the participants you need. In most cases, the contact will think you want to talk to the people who are responsible for purchasing or installing the software. If you are in fact seeking end users, be sure the person understands that you want to talk to the people who will be using the software after it has been purchased and installed. It is best not to hand your screener over to the customer contact. Instead, provide the person with the user profile (refer to Chapter 2, “User Profile” section, page 37) and have him or her e-mail you the names and contact information of people seeming to match this profile. You can then contact them yourself and run them through your screener to make sure they qualify.

It is important to note that companies often want to send their best and brightest people. As a result, it can be difficult to get a representative sample with customers. You should bring this issue up with the customer contact and say, “I don’t want only your best people. I want people with a range of skills and experience.”

Also, do not be surprised if the customer insists on including “special” users in your study. Often, supervisors will insist on having their input heard before you can access their employees (the true end users). Even if you do not need feedback from purchasing decision-makers or supervisors, you may have to include them in your activity. It may take longer to complete your study with additional participants, but the feedback you receive could be useful. At the very least, you have created a more positive relationship with the customer by including those “special” users.

Preventing No-Shows

Regardless of your recruitment method, you will encounter situations where people who have agreed to participate do not show up on the day of the activity. This is very frustrating. The reason could be that something more important came up, or the participant might have just completely forgotten. There are some simple strategies to try and prevent this from occurring.

Provide Contact Information

Participants are often recruited one to two weeks before the activity begins. When we recruit, participants are given a contact name, e-mail, and phone number and told to contact this person if they will not be able to make the session for any reason. We understand that people do have lives and that our activity probably ranks low in the grand scheme of things. We try to emphasize to participants that we really want them to participate, but we will understand if they cannot make the appointment. We let them know that we really appreciate when people take the time to call and cancel or reschedule; it allows us an opportunity to find someone else or to at least make good use of our time instead of waiting around for someone who is not going to show up. We want them to know that it is the people who do not appear who cause the most difficulty.

Remind Them

The day before, and on the day of the activity, contact the participants to remind them. Some people just simply forget, especially if it is on a Monday morning! A simple reminder can prevent this.

Try to phone people rather than e-mail them, because you need to know whether or not they will be coming. If you catch them on the phone, you can get this immediately. Also, you can reiterate a couple of very important points to them. Remind them that they must be on time for the activity and they must bring a valid ID (if required), or they will not be admitted to the session. If you send an e-mail, you will have to hope that people read it carefully and take note of these important details. Also, you will have to wait for people to respond to confirm. Sometimes, people do not read your e-mail closely, and they do not respond (especially, if they know they are not coming). If participants cannot be reached by phone and you must leave a voice mail, remind them about the date and time of the session and all of the other pertinent details. Ask them to call you back to confirm their attendance.

Over-recruit

Even though you have provided your participants with contact information to cancel and you have called to remind them, there are still people who will not show up. To counteract this problem, you can over-recruit participants. It is useful to recruit one extra person for every four or five participants needed; some colleagues even double recruit—two people for every one needed!

Sometimes, everyone will show up, but we feel this cost is worth it. It is better to have more people than not enough. When everyone shows, you can deal with this in a couple of ways. If it is an individual activity, you can run the additional sessions (it costs more time and money but you get more data) or you can call and cancel the additional sessions. If participants do not receive your cancellation message in time and they appear at the scheduled time, you should pay them the full incentive for their trouble.

If everyone shows up for a group activity, we typically keep all participants. An extra couple of participants will not negatively impact your session. If there is some reason why you cannot involve the additional participants, you will have to turn them away. Be sure to pay them the full amount for their trouble.

Recruiting International Participants

Depending on the product you are working on and its market, you may need to include participants from other countries. You cannot assume that you can recruit for or conduct the activity in the same manner as you would in your own country. Below are some pieces of advice to keep in mind when conducting international user research activities (Dray & Mrazek, 1996):

■ Use a professional recruiting agency in the country where you will be conducting the study. It is highly unlikely you will know the best places or methods for recruiting your end users.

■ Learn the cultural and behavioral taboos and expectations. The recruiting agency can help you, or you can check out several books specifically for this. (Refer to “Suggested Resources for Additional Reading” section on page 148 for more information.)

■ If your participants speak another language, you will need a translator, unless you are perfectly fluent. Even if your user speaks your language, you will need a translator. The participants will likely be more comfortable speaking in their own language or could have some difficulty understanding some of your terminology, if they are not fluent. There are often slang or technical terms that you will miss out on, despite being well-versed in the foreign language.

■ If you are doing in-home studies in some countries in Europe, not only is it unusual to go to someone’s home for an interview or other activities, but it is also unusual for guests to bring food to someone’s home. Since you are a foreigner, or because the study is unusual, bringing food will likely be accepted.

■ Punctuality can be an issue. For example, you must be on time when observing participants in Germany. In Korea or Italy, however, time is somewhat relative—appointments are more like suggestions and very likely will not begin on time. Keep this in mind when scheduling multiple visits in one day.

■ Pay attention to holiday seasons. For example, you will be hard-pressed to find European users to observe in August, since many Europeans go on vacation at that time. Also, countries with a large Islamic population will likely be unavailable during Ramadan.

Recruiting is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to conducting international field studies. You cannot simply apply a user research method in a foreign country in the same way that you would in your own country.

Recruiting Special Populations

There are a number of special considerations when recruiting special populations of users. These populations can include such groups as children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. This section discusses some things to consider. Sometimes, special populations require more time to recruit, so factor that into your plan.

Transportation

You may need to arrange transportation for people who are unable to get to the site of the activity. You should be prepared to arrange for someone to pick them up before the activity and drop them off at the completion of the activity. This could be done using taxis, or you could arrange to have one of your employees do it. Also, if it is possible, you should consider going to the participant rather than having him or her come to you.

Escorts

Some populations may require an escort. For example, in the case of participants under the age of 18, a legal guardian must accompany them. You will also need this guardian to sign all consent and confidential disclosure forms. You may also find that adults with disabilities or the elderly may require an escort. This is not a problem. If the escort is present when the user research session is being conducted, simply ask him or her to sit quietly and not interfere with the session. It is most important for the participant to be safe and feel comfortable (refer to Chapter 3, “Ethical Considerations” section, page 67). This takes priority over everything else.

Facilities

Find out whether any of your participants have special needs with regard to facilities as soon as you recruit them. If any of your participants have physical disabilities, you must make sure that the facility where you will be holding your activity can accommodate people with disabilities. You should ensure that it has parking for the handicapped, wheelchair ramps, and elevators and that the building is wheelchair-accessible in all ways (bathroom, doorways, etc.). Also keep in mind that the facility may need to accommodate a dog if any of your participants use one as an aid.

If you are bringing children to your site, it is always a nice idea to make your space “kid-friendly.” Put up a few children’s posters. Bring a few toys that they can play with during a break. A few small touches can go a long way to helping child participants feel at ease.

Online Services

There are many vendors available to conduct studies on your online product. A simple web search for “online usability testing” will highlight those vendors. They can conduct research methods like surveys, card sorting, and usability evaluations online. Most provide their own panel of participants for your study. These are most likely nonprobability-based samples and may be rife with professional participants (refer to Chapter 10, “Probability Versus Nonprobability Sampling” section, page 271). Some allow you to conduct the research yourself using their tools and your own participants (e.g., from your customer database), so be sure to ask.

If they are recruiting, you must indicate your desired user profile and provide a script for the participants to follow. They also may require you to provide a link to your site/product, upload a prototype, or provide other content (e.g., names of your features in your product for card sorting). The vendor then e-mails study invitations to members of their panel that meet your user profile. Within hours, you can get dozens of completed responses, sometimes with videos of the participants’ think-aloud commentary. Be aware that, although participants may be under an NDA, there is a greater risk of confidential product details being leaked. If this is not a concern for you, the online data collection is an excellent way to get feedback quickly from a large sample across the country.

Crowd Sourcing

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, or MTurk (http://www.mturk.com), is a popular method for quick recruiting and getting quick feedback from a large sample on microtasks (i.e., tasks that take a few seconds to a couple minutes to complete). Depending on the length and complexity of your tasks, each completed response can cost less than a dollar (sometimes just pennies!). This is an affordable way to get feedback from a large sample fast! MTurk participants are slightly more demographically diverse than standard Internet samples and significantly more diverse than typical American college samples (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011); however, like other research panels, MTurk has a set of “professional participants” known as “super-Turkers” that spend 20 + hours/week completing tasks (Bohannon, 2011). You can include some screener questions, but this method is really best for basic tasks that are applicable across a broad spectrum of users, not highly trained or domain-specific users. To ensure more reliable and valid responses, include ways to check that participants are reading your tasks and responding completely (e.g., throw out responses that are too quick, look for straight lining, include test questions, minimum character count for open-ended questions) (Kittur, Chi, & Suh, 2008). If possible, make it just as easy for participants to provide valid responses as it is to try to “cheat” the system (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Casler, Bickel, & Hackett, 2013).

Tracking Participants

When recruiting, there are a number of facts about the participants that you need to track. To help you accomplish this, set up a database that lists all of the participants that you contact. This can be the beginning of a very simple participant database. You will want to track such things as:

■ The activities they have participated in

■ The date of the activity

■ How much they were paid

■ Any negative comments regarding your experience with the participant (e.g., “user did not show up,” “user did not participate,” “user was rude”)

■ Any positive comments (e.g., “Nikhil was a great contributor”)

■ Current contact information (e-mail address, phone number)

Tax Implications

If any participant is paid over $600 in one calendar year in the United States, your organization will be required to complete and submit a 1099 tax form ($600 threshold based on time of publication). Failure to do so can get your organization into serious trouble. To track this, you will need to know how much each participant has been paid each calendar year. If you want to avoid submitting tax forms, as soon as an individual reaches the $550 mark, move him or her to a watch list (see below), because when he or she hits $600, you will have to complete the forms. This list should be reviewed prior to recruiting. Keep in mind that you must account for the retail value of swag you give participants, just as if they were cash or gift cards. If you have a small set of users providing ongoing feedback on one of your products (e.g., a wearable computing device) and the individuals get to keep it after the study is over, you must account for the full retail value of that device, not what your company paid for it. If the retail price of that device will be $600 or more, you will have to submit the tax forms.

The Professional Participant

Believe it or not, there are people who seem to make a career out of participating in user research activities and market research studies. Some are just genuinely interested in your studies, but others are genuinely interested in the money. You definitely want to avoid recruiting the latter.

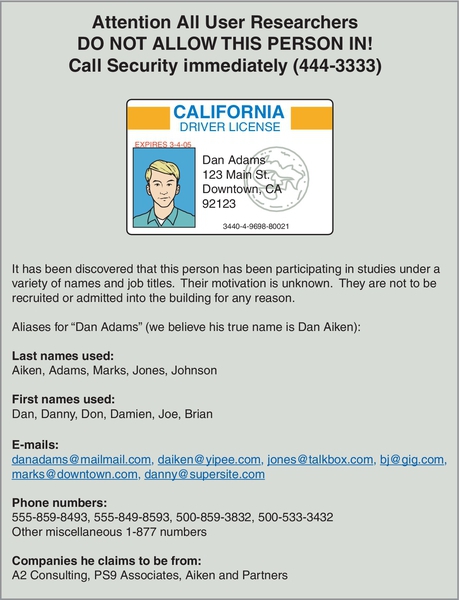

We follow the rule that a person can participate in an activity once every three months or until he or she reaches the $600/year mark (see “Tax Implications” section above). Unfortunately, there are some people who do not want to play by these rules. We have come across people who have changed their names and/or job titles in order to be selected for studies. We are not talking about subtle changes. In one case, we had a participant who claimed to be a university professor one evening and a project manager another evening—we have compiled at least nine different aliases, phone numbers, and e-mail addresses for this participant! The good news is that these kinds of people tend to be the rare exceptions.

By tracking the participants you have used in the past, you can take the contact information you receive from your recruits and make sure that it does not match the contact information of anyone else on your list. When we discover people who are using aliases, or who we suspect are using aliases, we place them on a watch list (see below).

We also attempt to prevent the alias portion of the problem by making people aware during the recruiting process that they will be required to bring a valid government-issued ID (e.g., driver’s license, passport). If they do not bring their ID, they will not be admitted into the activity. You need to be strict about this. It is not good enough to fax a photocopy or send an e-mail of the license before or after the activity. The troublesome participant described above actually altered her driver’s license and e-mailed it to us to receive the incentive she had been denied the night before.

Create a Watch List

The watch list is an important item in your recruiting toolbox. It is where you place the names of people you have recruited in the past but do not want to recruit in the future. These people can include those who:

■ Are close to or have reached the $600 per calendar year payment limit (you can remove them from the watch list on January 1st)

■ Have been dishonest in any way (e.g., used an alias, changed job role without a clear explanation)

■ Have been poor participants in the past (e.g., rude, did not contribute, showed up late)

■ Did not show up for an activity

The bottom line is that you want to do all you can to avoid bringing in participants who do not help the research goals. Again, in the case of our troublesome participant, she managed to sweet-talk her way into more than one study without a driver’s license (“I left it in my other purse” and “I didn’t drive today”). As a result, we posted warning signs for all researchers in our group. We even included her picture. See Figure 6.5 for an example of a “Warning” poster.

Creating a Protocol

A protocol is a script that outlines all procedures you will perform as a moderator and the order in which you will carry out these procedures. It acts as a checklist for all of the session steps and may be required if you are seeking Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for your study (see Chapter 3, page 66).

The protocol is very important for a number of reasons. First, if you are running multiple sessions of the same activity (e.g., two focus groups), it ensures that each activity and each participant is treated consistently. If you run several sessions, you tend to get tired and may forget details. The protocol helps you keep the sessions organized and polished. If you run the session differently for each activity, you will impact the data that you receive for each session. For example, if the two groups receive different sets of instructions, each group may have a different understanding of the activity and hence produce different results.

Second, the protocol is important if there is a different person running each session. This is never ideal, but the reality is that it does happen. The two people should develop the protocol together and rehearse it.

Third, a protocol helps you as a facilitator to ensure that you relay all of the necessary information to your participants. There is typically a wealth of things to convey during a session, and a protocol can help ensure that you cover everything. It could be disastrous if you forgot to have everyone sign your confidential disclosure agreements—and imagine the drama if you forgot to pay them at the end of the session.

Finally, a protocol allows someone else to replicate your study, should the need arise.

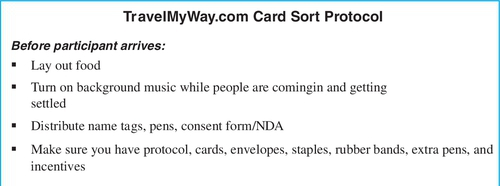

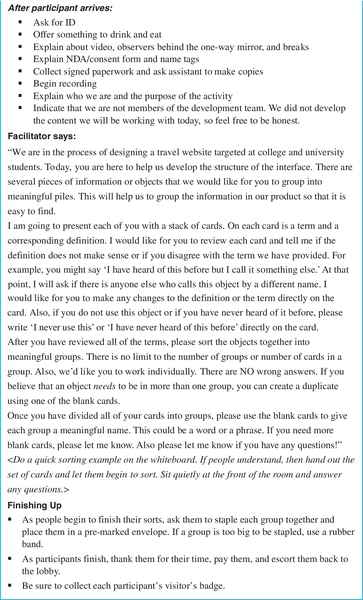

Sample Protocol

Figure 6.6 is a sample protocol for a group card-sorting activity. Of course, you need to modify the protocol according to the activity you are conducting, but this one should give you a good sense of what it should contain.

Piloting Your Activity

A pilot is essentially a practice run for your activity. It is a mandatory element for any user research activity. These activities are complex, and even experienced user researchers need to conduct a pilot. You cannot conduct a professional activity without a pilot. It is more than “practice;” it is debugging. Run the activity as though it is the true session. Do everything exactly as you plan to for the real session. Get a few of your colleagues to help you out. If you are running a group activity that requires 12 people, you do not need to get 12 people to participate in the pilot. (It would be great if you could, but it usually is not realistic or necessary.) Three or four colleagues will typically help you accomplish your purpose. We recommend running a pilot about three days before your session; this will give you time to fix any problems that crop up.

Conducting a pilot can help you accomplish a number of goals.

Is the Audiovisual Equipment Working?

This is your chance to set camera angles, check microphones, and make sure that the quality of recording is going to be acceptable. You do not want to find out after the session that the video camera or tape recorder was not working.

Clarity of Instructions and Questions

You want to make sure that instructions to the participants are clear and understandable. By trying to explain an activity to colleagues ahead of time, you can get feedback about what was understandable and what was not so clear.

Find Bugs or Glitches

A fresh set of eyes can often pick up bugs or glitches that you have not noticed. These could be anything from typos in your documentation to hiccups in the product you plan to demo. You will obviously want to catch these embarrassing oversights or errors before your real session.

Practice

If you have never conducted this type of activity before, or it has been a while, a pilot offers you an opportunity to practice and get comfortable. A nervous or uncomfortable facilitator makes for nervous and uncomfortable participants. The more you can practice your moderation skills, the better (refer to Chapter 7, “Moderating Your Activity” section, page 165).

The pilot will also give you a sense of the timing of the activity. Each activity has a predetermined amount of time, and you need to stay within that limit. By doing a pilot, you can find out whether you need to abbreviate anything.

Who Should Attend?

If this is the first time you have conducted this type of activity, it is advisable to have someone experienced in your pilot session. He or she will be able to give you feedback about what can be improved. After the pilot, if you do not feel comfortable executing the activity due to inexperience as a moderator, you will seriously want to consider having someone experienced (a colleague or consultant) step in for you. You can then shadow the experienced moderator to increase your comfort level for next time. Members of the product team or your advisor, if you are a student, should attend your pilot session. They are a part of your team for this activity, so you want them to be involved in every step—and this is an important step. Even though they have read your proposal (see “Getting Commitment” section, page 124), they may not have a good sense of how the activity will “look.” The pilot will give them this sense. It also gives the product team members one last chance to voice any concerns or issues. Be prepared for some possible critical feedback. If you feel their concerns are legitimate, you now have an opportunity to address them.

Ironically, the pilot is the one session to which you may feel uncomfortable inviting team members because you may be nervous and because events do go awry at pilots. But if you explain the nature and purpose of pilots to the team and set their expectations, they can help you without causing you to feel threatened.

Pulling It All Together

Preparation is the key to a successful user research activity. Be sure to get the product team involved in the preparation immediately, and work together as a team. In this chapter, we have covered all the key deliverables and action items that you and your product team will need to complete in order to prepare for a successful user research activity.