Surveys

Introduction

Surveys can be an extremely effective way to gather information from a large sample in a relatively short period of time. The problem is that a valid and reliable survey can be very difficult to design; yet surveys are perceived as very easy to create. It is just a bunch of questions, right? Well yes, but the questions you choose and how you ask them are critical. A poorly designed survey can provide meaningless or—even worse—inaccurate information. Additionally, how you choose your survey respondents will greatly impact the validity and reliability of your data. In this chapter, we hope to enlighten you about this process. Surveys can provide you with great data, but you must be familiar with the rules of creation and collection and the particulars of analyzing survey data, which is very different from log files or behavioral data. In this chapter, we cover the key topics that are important to consider when designing a survey and analyzing the data. Our primary focus is on web surveys because that is the most common survey format today; however, we also discuss paper and telephone surveys, as they offer unique benefits. In addition, we share an industry case study with you to show how Google uses surveys to track user sentiment over time.

When Should You Use a Survey?

Whether it is for a brand-new product or a new version of a product, a survey can be a great way to start your user research. In the case of a new product, surveys can be used to:

■ Help you identify your target user population

■ Help you identify current pain points and opportunities that your product could fulfill

■ Find out at a high level how users are currently accomplishing their tasks

In the case of an existing product, a survey can help you to:

■ Learn about your current user population and their characteristics

■ Find out the users’ likes/dislikes about the current product and track user sentiment over time

■ Learn how users currently use the system

Also, whether it is for a new or existing product, surveys are a way to reach a larger number of people than other methods typically allow. Surveys can be provided to users as a standalone research activity or as a supplement to other user activities (e.g., following a card sort).

Things to Be Aware of When Using a Survey

As with any user research technique, there are always factors that you must be aware of before you conduct a survey. Here, we describe several types of bias you need to be aware of and ways to mitigate them.

Selection Bias

Some users/customers/respondents are easier to contact and recruit than others. You can create a selection bias (i.e., the systematic exclusion of some unit from your data set) by conducting convenience sampling (i.e., recruiting based on convenience). These might be people who have signed up to be your participant database, students and staff at your university, friends and family, colleagues, etc. Obviously, getting responses only from those that are most convenient may not result in accurate data.

Nonresponse Bias

The unfortunate reality of surveys is that not everyone is going to respond and those that do choose to respond may be systematically different from those who do not. For example, very privacy-conscious individuals may be unlikely to respond to your survey, and this would be a real problem if you are interested in feedback on your privacy policy. Experienced survey researchers give response rate estimates of anywhere between 20% and 60%, depending on user type and whether incentives are offered or not. In our experience, you are likely to get a response rate closer to 20%, unless you have a very small, targeted population that has agreed to complete your survey ahead of time. However, there are some things you can do to improve the response rate:

■ Personalize it. Include a cover letter/e-mail or header at the top of the survey with the respondent’s name to provide information about the purpose of the study and how long it will take. Tell the respondents how important their feedback is to your organization. Conversely, incorrectly personalizing it (e.g., wrong name or title) can destroy your response rate.

■ Keep it short. We recommend 10 minutes or less. It is not just about the number of questions. Avoid long essay questions or those that require significant cognitive effort.

■ Make it easy to complete and return. For example, if you are sending surveys in the mail, include a self-addressed envelope with prepaid postage.

■ Follow up with polite reminders via multiple modes. A couple of reminders should be sufficient without harassing the respondent. If potential respondents were initially contacted via e-mail, try contacting nonrespondents via the phone.

■ Offer a small incentive. For example, offering participants a $5 coffee card for completing a survey can greatly increase the response rate. At Google, we have found that raffles to win a high-price item do not significantly increase response rates.

Satisficing

Satisficing is a decision-making strategy where individuals aim to reach satisfactory (not ideal) results by putting in just enough effort to meet some minimal threshold. This is situational, not intrinsic to the individual (Holbrook, Green, & Krosnick, 2003; Vannette & Krosnick, 2014). By that, we mean that people do not open your survey with a plan to satisfice; it happens when they encounter surveys that require too much cognitive effort (e.g., lengthy, difficult-to-answer questions, confusing questions). When respondents see a large block of rating scale questions with the same headers, they are likely to straight-line (i.e., select the same choice for all questions) rather than read and consider each option individually. Obviously, you want to make your survey as brief as possible, write clear questions, and make sure you are not asking things a participant cannot answer.

Your survey mode can also increase satisficing. Respondents in phone sureys demonstrated more satisficing behavior than in face-to-face surveys (Holbrook et al., 2003) and online surveys (Chang & Krosnick, 2009). However, within online samples, there was greater satisficing among probability panels than nonprobability panels (Yeager et al., 2011). Probability sampling (aka random sampling) means that everyone in your desired population has an equal, nonzero chance of being selected. Nonprobability sampling means that respondents are recruited from an opt-in panel that may or may not represent your desired population. Because respondents in nonprobability panels pick and choose which surveys to answer in return for an incentive, they are most likely to only pick those they are interested in and comfortable answering (Callegaro et al., 2014).

Additionally, you can help avoid satisficing by offering an incentive, periodically reminding respondents how important their thoughtful responses are, and communicating when it seems they are answering the questions too quickly. When you test your survey, you can get an idea for how long each question should take to answer, and if the respondent answers too quickly, some online survey tools allow you to provide a pop-up that tells respondents, “You seem to be answering these questions very quickly. Can you review your responses on this page before continuing?” If a respondent is just trying to get an incentive for completing the survey, you should notify him or her that he or she will not be able to do it quickly. He or she may quit at this point but it is better to avoid collecting invalid data.

Acquiescence Bias

Some people are more likely to agree with any statement, regardless what it says. This is referred to as acquiescence bias. Certain question formats are more prone to bring out this behavior than others and should be avoided (Saris, Revilla, Krosnick, & Shaeffer, 2010). These include asking respondents if or how much they agree with a statement, any binary question (e.g., true/false, yes/no), and, of course, leading questions (e.g., “How annoyed are you with online advertising?”). We will cover how to avoid these pitfalls later in the chapter.

Creating and Distributing Your Survey

One of the biggest misconceptions about a survey is the speed with which you can prepare for, collect, and analyze the results. A survey can be an extremely valuable method, but it takes time to do it correctly. In this section, we will discuss the preparation required for this user research method.

Identify the Objectives of Your Study

Do not just jump in and start writing your survey. You need to do some prep work. Ask yourself the following:

■ Who do we want to learn about? (refer to Chapter 2, “Learn About Your Users” section, page 35)

■ What information are you looking for (i.e., what questions are you trying to answer)?

■ How will you distribute the survey and collect responses?

■ How will you analyze the data?

■ Who will be involved in the process?

It is important to come up with answers to these questions and to document your plan. As with all user research activities, you should write a proposal that clearly states the objectives of your study (refer to Chapter 6, “Creating a Proposal” section, page 116). The proposal should also explicitly state the deliverables and include a timeline. Because you normally want to recruit a large number of participants, it can be resource-intensive to conduct a survey. There are more participants to recruit and potentially compensate, as well as more data to analyze than for most user research activities. As a result, it is important to get your survey right the first time and get sign-off by all stakeholders. A proposal can help you do this.

Players in Your Activity

A survey is different from the other activities described in this book because—unless it is a part of another activity—you are typically not present as the survey is completed. As a result, there is no moderator, no notetaker, no videographer, etc. The players are your participants, but now, we will refer to them as respondents.

The first thing to determine is the user population (refer to Chapter 2, “Learn About Your Users” section, page 35). Who do you plan to distribute this survey to? Are they the people registered with your website? Are they using your product? Are they a specific segment of the population (e.g., college students)? Who you distribute your survey to should be based on what you want to know. The answers to these questions will impact the questions you include.

Number of Respondents

You must be sure that you can invite enough people from your desired user population (e.g., current users, potential users) to get a statistically significant response. That means that you can be confident that the results you observe are not the product of chance. If your sample is too small, the data you collect cannot be extrapolated to your entire population. If you cannot increase your sample size, do not despair. At that point, it becomes a feedback form. A feedback form does not offer everyone in your population an equal chance of being selected to provide feedback (e.g., only the people on your mailing list are contacted, it is posted on your website under “Contact Us” and only people who visit there will see it and have the opportunity to complete it). As a result, it does not necessarily represent your entire population. For example, it may represent only people that are fans and signed up for your mailing list or customers that are particularly angry about your customer service and seek out a way to contact you. On the other hand, you do not need (nor want!) to collect responses from everyone in your population. That would be a census and is not necessary to understand your population.

To determine how many responses you need, there are many free sample-size calculators available online. To use them, you will need to know the size of your population (i.e., the total number of people in the group you are interested in studying), the margin of error you can accept (i.e., the amount of error you can tolerate), desired confidence interval (i.e., the amount of uncertainty you can accept), and the expected response distribution (i.e., for each question, how skewed do you expect the response to be). If you do not know what the response distribution will be, you should leave this as 50%, which will result in the largest sample size needed. Let us continue with our travel example. If we are interested in getting feedback from our existing customer base, we need to identify how large that population is. We do not know what our response distribution is, so we will set it at 50%. If our population is 23,000 customers and we are looking for a margin of error of ± 3% and confidence interval (CI) of 95%, we will need a sample size (i.e., number of completed responses) of 1020. This is the minimum number of responses you will want to collect for your desired level of certainty and error, but of course, you will have to contact far more customers than that to collect the desired number of completes. The exact number depends on many factors, including the engagement of your population, survey method (e.g., phone, paper, web), whether or not you provide an incentive, and how lengthy or difficult your survey is, among other factors. (Note that sample sizes do not increase much for populations above 20,000.)

Probability Versus Nonprobability Sampling

As with any other research method, you may want or need to outsource the recruiting for your study. In the case of surveys, you would use a survey panel to collect data. These are individuals who are recruited by a vendor based on the desired user characteristics to complete your survey. Perhaps you are not interested in existing customers and therefore have no way to contact your desired population. There are many survey vendors available (e.g., SSI, YouGov, GfK, Gallup), and they vary in cost, speed, and access to respondents. The key thing you need to know is whether they are using probability or nonprobability sampling. Probability sampling might happen via a customer list (if your population is composed of those customers), intercept surveys (e.g., randomly selected individuals who visit your site invited via a link or pop-up), random digit dialing (RDD), and address-based sampling (e.g., addresses are selected at random from your region of interest). In this case, the vendor would not have a panel ready to pull from but would need to recruit fresh for each survey. Nonprobability sampling involves panels of respondents owned by the vendor that are typically incentivized per survey completed. The same respondents often sign up for multiple-survey or market research panels. The vendors will weight the data to try to make the sample look more like your desired population. For example, if your desired population of business travelers is composed of 70% economy, 20% business, and 10% first-class flyers in the real world but the sample from the panel has only 5% business and 1% first-class flyers, the vendor will multiply the responses to increase the representation of the business and first-class flyers while decreasing the representation of the economy flyers. Unfortunately, this does not actually improve the accuracy of the results when compared with those from a probability-based sample (Callegaro et al., 2014). In addition, nonprobability-based samples are more interested in taking surveys and are experts at it.

Compose Your Questions

Previously, you identified the objectives of your survey. Now, it is time to create questions that address those objectives. Recommendations in this section will also help increase completion rates for your survey. This stage is the same regardless of how you plan to distribute your survey (e.g., paper, web). However, the formatting of your questions may vary depending on the distribution method. The stage of “building” your survey and the impact of different distribution methods are discussed later in this chapter.

Identify Your Research Questions and Constructs

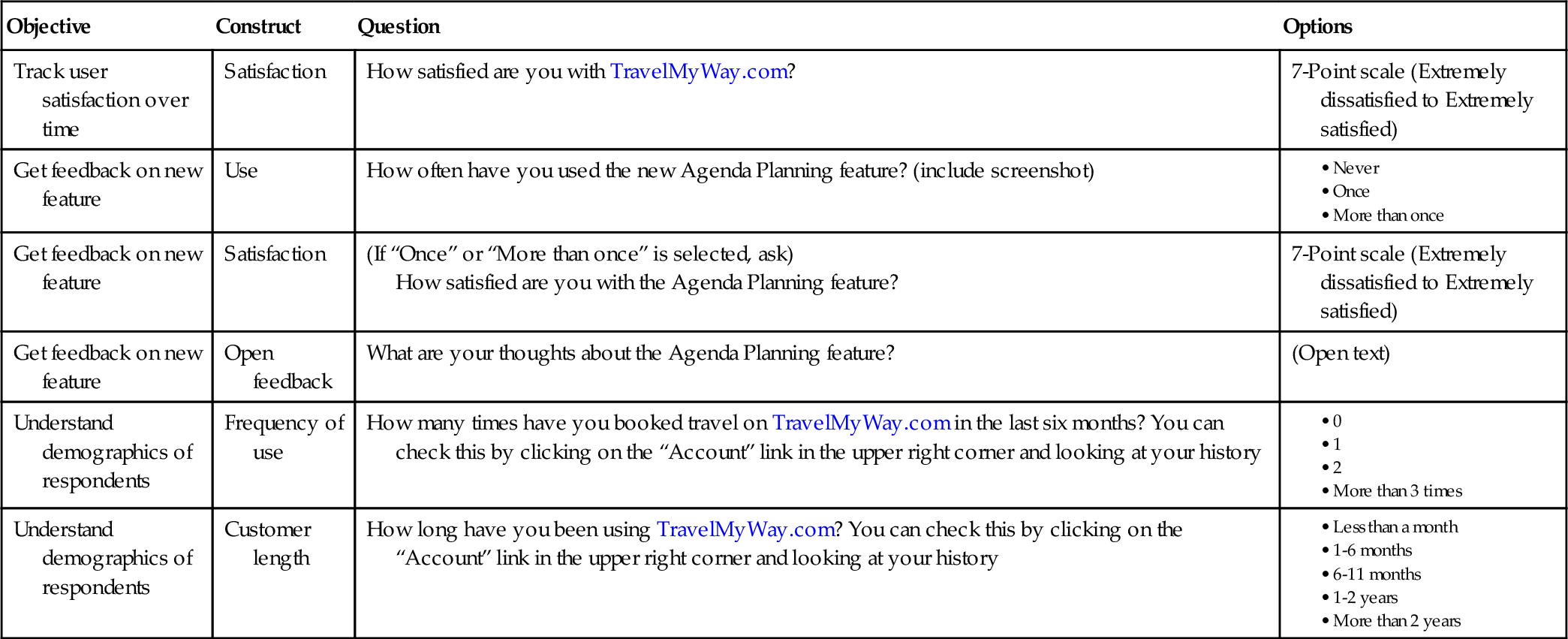

For each objective, you need to identify your research question(s) and the constructs you want to measure to answer those questions. We recommend creating a table to help with this. Table 10.1 is a sample table of what you might create for TravelMyWay.com. This is your first draft and you will likely need to iterate on it but working from this table will help avoid questions that are not directly tied to your objective, track branching logic, and help you group similar questions to avoid redundancy.

Table 10.1

Sample table of objectives, constructs, and questions

| Objective | Construct | Question | Options |

| Track user satisfaction over time | Satisfaction | How satisfied are you with TravelMyWay.com? | 7-Point scale (Extremely dissatisfied to Extremely satisfied) |

| Get feedback on new feature | Use | How often have you used the new Agenda Planning feature? (include screenshot) |

• Once • More than once |

| Get feedback on new feature | Satisfaction | (If “Once” or “More than once” is selected, ask) How satisfied are you with the Agenda Planning feature? | 7-Point scale (Extremely dissatisfied to Extremely satisfied) |

| Get feedback on new feature | Open feedback | What are your thoughts about the Agenda Planning feature? | (Open text) |

| Understand demographics of respondents | Frequency of use | How many times have you booked travel on TravelMyWay.com in the last six months? You can check this by clicking on the “Account” link in the upper right corner and looking at your history |

• 1 • 2 • More than 3 times |

| Understand demographics of respondents | Customer length | How long have you been using TravelMyWay.com? You can check this by clicking on the “Account” link in the upper right corner and looking at your history |

• 1-6 months • 6-11 months • 1-2 years • More than 2 years |

Keep It Short

One of the key pieces of advice is to keep the survey short. If you ignore this rule, you are doomed to fail because no one will take the time to complete your survey.

There are several ways to keep your survey short:

■ Every question should be tied to an objective and (ideally) be actionable. One of your objectives may be to understand your user population or their context of use. You may want to track this over time. It is not necessarily actionable, but it can still be an important objective of the survey. Work with your stakeholders to find out the information they need to know and throw out “nice to know” or “curiosity” questions.

■ Use branching logic. Not every question will apply to every respondent. If a respondent has not used a feature, for example, do not ask him or her about his or her satisfaction with the feature. Adding “If you have used feature X” at the beginning of the question does not help. You are taking up valuable space and time by making the respondent read it, and there is a good chance that the respondent will answer it anyway. A user’s satisfaction with a feature he or she does not use is not helpful in making decisions.

■ Do not ask questions that respondents cannot answer validly. Just like you do not want to ask people about features they do not have experience with, you do not want to ask them to predict the future (e.g., How often would use a feature that does X?) or to tell you about things that happened long ago, at least not without assistance. If you want to know if a respondent is a frequent customer based on how often he or she uses your product, you can ask him or her how often he or she has used the product in a given time frame, as long as there is an easy way for him or her to find this information (e.g., provide instructions for how to look in his or her account history).

■ No essay questions. You do not need to avoid open-ended questions (OEQs) but use them only when appropriate and do not seek lengthy, detailed responses. See the discussion on writing OEQs on page 276.

■ Avoid sensitive questions. This is discussed in the next section, but the general rule is to avoid asking sensitive questions unless you really need the information to make decisions.

■ Break questions up. If you have a long list of questions that are all critical to your objective(s), you have a couple options for shortening the survey. One is to divide the questions into a series of shorter surveys. This works well if you have clearly defined topics that make it easy to group into smaller surveys; however, you will lose the ability to do analysis across the entire data set. For example, if you want to know about the travel preferences for those that travel by train and plane, you could divide the questions into a train survey and a plane survey, but unless you give the survey to the same sample and are able to identify who completed each survey, you will not be able to join the data later and see correlations between those that travel by train and plane. Another option is to randomly assign a subset of the questions to different respondents. You will need a much larger sample size to ensure that you get a significant number of responses to every question, but if you are successful, you will be able to conduct analysis across the entire data set.

If you can adhere to these rules, then your survey will have a much greater chance of being completed.

Asking Sensitive Questions

Both interviews and surveys have pros and cons with regards to asking sensitive questions. In an interview, you have the opportunity to develop a rapport with the respondent and gain his or her trust. But even if the respondent does trust you, he or she may not feel comfortable answering the question in person. If your survey is anonymous, it is often easier to discuss sensitive topics that would be awkward to ask face-to-face (e.g., age, salary range). However, even in anonymous surveys, people may balk at being asked for this type of information or you may encounter social desirability bias (i.e., people responding with the answer they think is most socially acceptable, even if it is not true for them).

Ask yourself or your team whether you really need the information. Demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, salary range, education) are often asked because it is believed that these are ‘standard’ questions, but behavioral factors (e.g., how frequently they use your product, experience with a competitor’s product) are usually more predictive of future behavior than demographic data. If you are convinced that the answers to sensitive questions will help you better understand your user population and therefore your product, provide a little verbiage with the question to let respondents know why you need this information, for example, “To help inform decisions about our privacy policy, we would like to know the following information.”

Clearly mark these questions as “optional.” Never make them required because either respondents will refuse to complete your survey or they may purposely provide inaccurate information just to move forward with the survey if you offered an incentive for completion. Finally, save these questions for the end of the survey. Allow participants to see the type of information you are interested in, and then, they can decide if they want to associate sensitive information with it.

Question Format and Wording

Once you have come up with your objectives, constructs, and list of questions, you will need to determine their wording and format. By “format,” we are referring to how the respondents are expected to respond to the question and the layout and structure of your survey. Participants are far more likely to respond when they perceive your survey as clear, understandable, concise, of value, and of interest.

Response Format

For each of your questions, you must decide the format in which you want the participant to respond: either from a set of options you provide or through free response. OEQs allow the respondents to compose their own answers, for example, “What is one thing you would like to see changed or added to TravelMyWay.com?” Closed-ended questions require participants to answer the questions by either:

■ Providing a single value or fact

■ Selecting all the values that apply to them from a given list

■ Providing an opinion on a scale

There are several things to keep in mind with OEQs:

■ Data analysis is tedious and complex because it is qualitative data that must first be coded before you can analyze them.

■ Because respondents use their own words/phrases/terms, responses can be difficult to comprehend and you typically will not have an opportunity to follow up and clarify with the person who responded.

■ They can make the survey longer to complete, thereby decreasing the return rate.

The bottom line is do not ask for lengthy OEQs. They are best used when:

■ You do not know the full universe of responses to write a closed-ended question. You can conduct your survey with a small sample of respondents, analyze the answers to the OEQ in this case, and then categorize them to create your options for a close-ended question for the rest of your sample.

■ There are too many options to list them all.

■ You do not want to bias respondents with your options but instead want to collect their top-of-mind feedback.

■ You are capturing likes and dislikes.

Clearly labeling OEQs as “optional” will increase the likelihood that respondents will complete your survey and only answer the OEQs where they feel that have something to contribute. Forcing respondents to answer OEQs will hurt your completion rate, increase satisficing, and may earn you gibberish responses from respondents that do not having something to contribute.

There are three main types of closed-ended question responses to choose from: multiple choice, rating scales, and ranking scales. Each serves a different purpose but all provide data that can be analyzed quantitatively.

Multiple-Choice Questions

In multiple-choice questions, respondents are provided with a question that has a selection of predetermined responses to choose from. In some cases, respondents are asked to select multiple responses, and in other cases, they are asked to select single responses. In either case, make sure that the options provided are either randomized to avoid a primacy effect (i.e., respondents gravitate to the first option they see) or, if appropriate, placed in a logical order (e.g., days of the week, numbers, size) (Krosnick, Li, & Lehman, 1990).

■ Multiple responses. Participants can choose more than one response from a list of options. This is ideal when the real world does not force people to make a single choice. See example:

■ Single response. Participants are provided with a set of options from which to choose only one answer. This is ideal in cases where the real world does limit people to a single choice. See example below:

■ Binary. As the name implies, the respondent must select from only two options, for example, “yes/no,” “true/false,” or “agree/disagree.” With binary questions, you are forcing participants to drop all shades of gray and pick the answer that best describes their situation or opinion. It is very simple to analyze data from these types of questions, but you introduce error by not better understanding some of the subtleties in their selection. Additionally, these types of questions are prone to acquiescence bias. As a result, you should avoid using binary questions.

Rating Scales

There are a variety of scale questions that can be incorporated into surveys. Likert scale and ranking scale are two of the most common scales.

The Likert scale is the most frequently-used rating scale. Jon Krosnick at Stanford University has conducted lengthy empirical research to identify the ideal number of scale items, wording, and layout of Likert scales to optimize validity and reliability (Krosnick & Tahk, 2008).

■ Unipolar constructs (i.e., units that go from nothing to a lot) are best measured on a 5-point scale. Some example unipolar constructs include usefulness, importance, and degree. The recommended scale labels are Not at all […], Slightly […], Moderately […], Very […], and Extremely […].

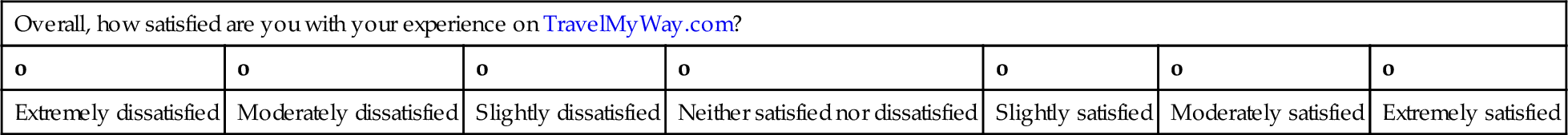

■ Bipolar constructs (i.e., units that have a midpoint and two extremes) are best measured on a 7-point scale. The most frequently used bipolar construct is satisfaction. The recommended scale labels are Extremely […], Moderately […], Slightly […], Neither […] nor […], Slightly […], Moderately […], and Extremely […].

In both cases, move from negative (e.g., Not at all useful, Extremely dissatisfied) to positive (e.g., Extremely useful, Extremely satisfied). The negative extreme is listed first to allow for a more natural mapping to how respondents interpret bipolar constructs (Tourangeau, Couper, & Conrad, 2004).

Providing labels on all points of the scale avoids ambiguity and ensures that all of your respondents are rating with the same scale in mind (Krosnick & Presser, 2010). These particular labels have been shown to be perceived as equally spaced and result in a normal distribution (Wildt & Mazis, 1978). Do not include numbers on your scale, as they add visual clutter without improving interpretation. Below is an example of a fully-labeled Likert scale.

| Overall, how satisfied are you with your experience on TravelMyWay.com? | ||||||

| o | o | o | o | o | o | o |

| Extremely dissatisfied | Moderately dissatisfied | Slightly dissatisfied | Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | Slightly satisfied | Moderately satisfied | Extremely satisfied |

Another type of rating scale question asks users to give a priority rating for a range of options, for example:

In this rating question, you are not comparing the options given against one another. As a result, more than one option can have the same rating.

Ranking Scales

This type of scale question gives participants a variety of options and asks them to provide a rank for each one. Unlike the rating scale question, the respondent is allowed to use each rank only once. In other words, the respondent cannot state that all four answers are “most important.” These questions can be cognitively more taxing. To make it easier, break it into separate questions. For example, first ask “What is your most preferred method for booking travel?” and then follow up with “What is your second most preferred method for booking travel?” and remove the option that the respondent selected in the previous question.

The ranking scale differs from a rating scale because the respondent is comparing the options presented against one another to come up with a unique ranking for each option.

Other

Avoid including “other” as an option in your closed-ended questions unless you are not sure you know the complete list of options a respondent may need. It is cognitively easier to choose it than to match the answer they have in mind to one of the options in your question. If “other” receives more than 3% of your total responses, categorize the responses and add additional options to your question.

Question Wording

Your choice of words for survey questions is critical. Regardless of the format, avoid vague options like “few,” “many,” and “often.” Participants will differ in their perception of those options, and it will be difficult for you to quantify them when you analyze the data. Avoid jargon and abbreviations for similar reasons. Not all respondents may recognize or interpret it the way you intended.

Double-barreled questions are a common pitfall. This is when two questions are combined as one, for example, “How satisfied are you with the customer support you received online and/or over the phone?” The problem is that respondents may have different answers for each piece of the question, but you are forcing them to pick a single answer. In that case, the respondents must choose if it is better to provide an average of how they feel, provide the best rating or the lowest rating, or simply satisfice and pick an option that does not accurately represent how they feel.

Statements Versus Questions

As mentioned earlier, binary (e.g., yes/no, true/false, agree/disagree) questions and statements lead to acquiescence bias. Instead of providing statements for respondents to reply to (whether binary or a rating scale), it is best to identify the construct you are interested in and then write a question to measure it. For example, instead of asking “How strongly do you agree with the statement ‘I prefer to fly rather take a train’?” or “True or False: ‘I prefer to fly rather than take a train,’” you should identify the construct of interest. In this case, it is mode of travel preference. You could measure this by asking the respondents to rank their modes of travel by preference or ask them how satisfied they are with each mode of travel.

Determine Now How You Will Analyze Your Data

Those who are new to survey methodologies have a tendency to wait until the data have been collected before they consider how they will be analyzed. An experienced researcher will tell you that this is a big mistake. You may end up collecting data that are unnecessary for you to answer your research questions or, worse, not collecting data that are necessary. Once your survey is closed, it is too late to get the data you need without launching another survey, and that is both expensive and time-consuming.

By thinking about your data analysis before you distribute your survey, you can make sure the survey contains the correct questions and options. Ask yourself the following questions:

■ What kind of analysis do you plan to perform (e.g., descriptive statistics, inferential statistics)? Go through each question and determine what you will do with the data. Identify any comparisons that you would like to make and document this information. This can impact the question format.

■ Are there questions that you do not know how to analyze? You should either remove them, do some research to figure out how to analyze them, or contact a statistics professional.

■ Will the analysis provide you with the answers you need? If not, perhaps you are missing questions.

■ Do you have the correct tools to analyze the data? If you plan to do data analysis beyond what a spreadsheet can normally handle (e.g., descriptive statistics), you will need a statistical package like SPSS™, SAS™, or R. If your company does not have access to such a tool, you will need to acquire it. Keep in mind that if you must purchase it, it may take time for a purchase order or requisition to go through. You do not want to hold up your data analysis because you are waiting for your manager to give approval to purchase the software you need. In addition, if you are unfamiliar with the tool, you can spend the time you are waiting for the survey data to come in to learn how to use the tool.

■ How will the data be entered into the analysis tool? This will help you budget your time. If the data will be entered manually (e.g., in the case of a paper survey), allot more time. If the data will be entered automatically via the web, you may need to write a script. If you do not know how to do this, make time to learn.

By answering these questions early on, you will help ensure that the data analysis goes smoothly. This really should not take a lot of time, but by putting in the effort up front, you will also know exactly what to expect when you get to this stage of the process, and you will avoid any headaches, lost data, or useless data.

Building the Survey

Now that you have composed your questions, you can move on to the next stage, which is building the survey in the format in which it will be distributed (e.g., paper, web, e-mail). There are a number of common elements to keep in mind when building your survey, regardless of the distribution method. These will be discussed first. Then, we look at elements unique to each distribution method.

Standard Items to Include

There are certain elements that every survey should contain, regardless of topic or distribution method.

Title

Give every survey a title. The title should give the respondent a quick sense of the purpose of the survey (e.g., TravelMyWay.com Customer Satisfaction Survey). Keep it short and sweet.

Instructions

Include any instructional text that is necessary for your survey as a whole or for individual questions. The more explicit you can be, the better. For example, an instruction that applies to the whole survey might be “Please return the completed survey in the enclosed self-addressed, postage-paid envelope.” An instruction that applies to an individual question might read, “Of the following, check the one answer that most applies to you.” Of course, you want to design the survey form and structure so that the need for instructions is minimized. A lengthy list of instructions either will not be read or will inhibit potential respondents from completing the survey.

Contact Information

There are many reasons why you should include contact information on your surveys. If a potential respondent has a question prior to completing the survey (e.g., When is it due? What is the compensation? Who is conducting the study?), he or she may choose to skip your survey if your contact information is not available. However, you should make every effort to include all relevant information in your survey, so respondents will have no need to contact you. Participants also have the right to be fully informed before consenting to your research so you are ethically obligated to provide them with a way to ask you questions.

If your survey was distributed via mail with a self-addressed envelope, it is still wise to include the return address on the survey itself. Without a return address on the survey, if the return envelope is lost, people will be unable to respond. And last but not least, providing your contact information lends legitimacy to the survey.

Purpose

In a line or two, tell participants why you are conducting the survey. Ethically, they have a right to know (refer to Chapter 3, “The Right to Be Informed” section, page 70). Also, if you have a legitimate purpose, it will attract respondents and make them want to complete the survey. A purpose could read something like the following:

TravelMyWay.com is conducting this survey because we value our customers and we want to learn whether our travel site meets their needs, as well as what we can do to improve our site.

Time to Complete

People will want to know at the beginning how long it will take to finish the survey before they invest their time into it. You do not want respondents to quit in the middle of your 15-minute survey because they thought it would take five minutes and now they have to run to a meeting. It is only fair to set people’s expectations ahead of time, and respondents will appreciate this information. If you do not provide it, many potential respondents will not bother with your survey because they do not know what they are getting into. Worse, if you understate the time to complete, you will violate the respondent’s trust and risk a low completion for the current survey and lower response rate for future surveys.

Confidentiality and Anonymity

You are obligated to protect respondents’ privacy (refer to Chapter 3 “Privacy,” page 66). Data collected from respondents should always be kept confidential, unless you explicitly tell them otherwise (refer to Chapter 3, “Anonymity,” page 66). Confidentiality means that the person’s identity will not be associated in any way with the data provided. As the researcher, you may know the identity of the participant because you recruited him or her; however, you keep his or her identity confidential by not associating any personally identifying information (PII) with his or her data. You should make a clear statement of confidentiality at the beginning of your survey.

Anonymity is different from confidentiality. If a respondent is anonymous, it means that even you, the researcher, cannot associate a completed survey with the respondent’s identity, usually because you did not collect any PII in the first place or you do not have access to it, if it is collected. Make sure that you are clear with respondents about the distinction. Web surveys, for example, are typically confidential but not anonymous. They are not anonymous because you could trace the survey (via an IP address or panel member ID number) back to the computer/individual from which it was sent. This does not necessarily mean that the survey is not anonymous because someone may use a public computer, but you cannot make this promise in advance. Be sure ahead of time that you can adhere to any confidentiality and/or anonymity statements that you make. In addition to informing respondents of whether their responses are confidential or anonymous, you should also point them toward your company’s privacy policy.

Visual Design

How your survey is constructed is just as important as the questions it contains. There are ways to structure a survey to improve the response rate and reduce the likelihood that respondents will complete the survey incorrectly.

Responsive Design

Increasingly, people are accessing information on mobile devices rather than desktop or laptop computers. This means that there is a good chance respondents will attempt to complete your survey on their phone or tablet. Using responsive design means that your online survey will scale to look great regardless of the size of the device. Check your survey on multiple mobile devices to ensure everyone can complete your survey with ease.

Reduce Clutter

Whether you are creating your survey electronically or on paper, avoid clutter. The document should be visually neat and attractive. Be a minimalist. Include a survey title and some instructional text, but avoid unnecessary headers, text, lines, borders, boxes, etc. As we mentioned earlier, it is imperative that you keep your survey short. Provide sufficient white space to keep the survey readable and one question distinguishable from another. A dense two-page survey (whether online or on paper) is actually worse than a five-page survey with the questions well spaced. Dense surveys take longer to read and it can be difficult to distinguish between questions.

Font Selection

You may be tempted to choose a small font size so that you can fit in more questions, but this is not advisable. A 12-point font is the smallest recommended. If you are creating an online survey, choose fonts that are comparable to these sizes. For web surveys, set relative rather than absolute font sizes so that users can adjust the size via their browsers. Remember that some respondents may complete your survey on a smartphone rather than a large computer monitor.

Font style is another important consideration. Choose a font that is highly readable. Standard sans serif fonts (fonts without tails on the characters, such as Arial or Verdana) are good choices. Avoid decorative or whimsical fonts, for example, Monotype Corsiva, as they tend to be much more difficult to read. Choose one font style and stick with it. NEVER USE ALL CAPS AS IT IS VERY DIFFICULT TO READ.

Use a Logical Sequence and Groupings

Surveys, like interviews, should be treated like a conversation. In a normal conversation, you do not jump from one topic to another without some kind of segue to notify the other person that you are changing topics. This would be confusing for the other person you are talking to, and the same is true in interviews and surveys. If your survey will cover more than one topic, group them together and add section headers to tell respondents you are moving on to a new topic.

Start with the simple questions first and then move toward the more complex ones to build a rapport. As discussed earlier, if you must include sensitive or demographic questions, leave them until the end of the survey and mark them as “optional.” Confirm during your pilot testing that the flow of the survey makes sense, especially in the case of surveys that include significant branching.

Considerations When Choosing a Survey Distribution Method

This section discusses a variety of factors that apply to each of the distribution methods. This information should enable you to make the appropriate distribution choice based on your needs.

Cost per Complete

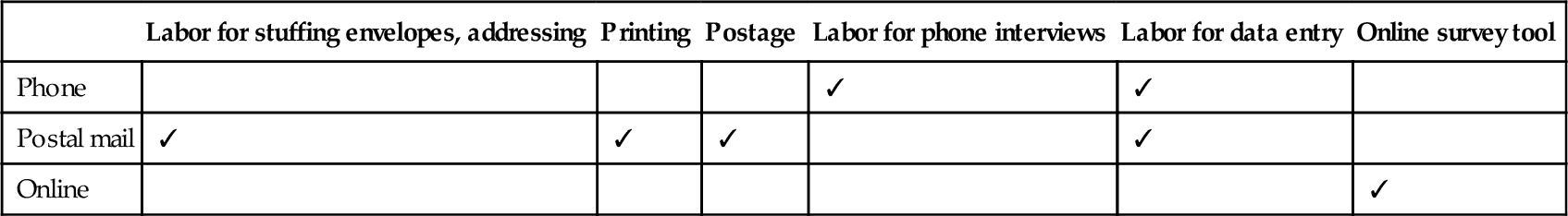

There are several collection costs one must keep in mind when considering which survey method to use. Unique costs per method are shown in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2

Costs per survey method

| Labor for stuffing envelopes, addressing | Printing | Postage | Labor for phone interviews | Labor for data entry | Online survey tool | |

| Phone | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Postal mail | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Online | ✓ |

Respondents

If you have a customer list, regardless of which method you use, there are no upfront costs for getting access to your desired population. If not, you must pay a vendor to recruit respondents. For a full discussion about selecting research vendors, refer to Chapter 6, “Recruiting Participants” section on page 126. The response rate is often higher when contacting your own customers because customers feel invested in improving the product or service they use. However, it is important to realize that your customer list may not be up-to-date. People move, change phone numbers (work and personal), and sometimes give “junk” e-mail addresses to avoid getting spam. To get an idea of what your overall response rate will be before contacting every customer in your database, send your survey through your desired means (i.e., e-mail invitation, phone, mail) to 100 customers and see how many respond. You may be surprised how many “bounced” e-mails or disconnected phone lines you encounter. If you have a well-developed marketing department that communicates with your customers via e-mail using tools, such as MailChimp or Constant Contact, they should have a good idea of the health and activity of your mailing list.

Labor

Labor costs of data analysis will be the same regardless of the method you choose. Until now, we have not talked a lot about the use of telephone surveys using RDD or a customer list. Phone surveys require labor costs to conduct the interviews over the phone and enter the data, whereas paper-based surveys require costs for paper and printing, labor costs to stuff and label the envelopes, postage (both to the respondent and back to you), and entering the data.

Time

Paper-based and phone surveys require more time to prepare and collect data. Allow time in your schedule to make copies of your paper-based survey and to stuff and address a large number of envelopes. Data entry also takes significant time. Do a trial data entry early on using one of your completed pilot surveys, so you can get a sense of just how long this will take. It is also wise to have a second individual check the data entry for errors. Experienced researchers can tell you that this always takes longer than expected. It is better to be aware of this ahead of time, so you can budget the extra time into your schedule.

Tools

Online surveys will most likely require the purchase of a license for an online survey tool, although some basic ones are free (e.g., Google Forms). However, there are no additional costs over the other methods. Phone and e-mail surveys can be created cheaply using any word processing document; however, you will likely want to use a survey tool for phone interviewers to directly enter responses and skip the data entry step later.

Response Rate

The upfront costs are not the only thing to consider when deciding which method to choose. Your response rate will vary depending on the survey mode you choose, so what you are really interested in calculating is the cost per complete (i.e., total costs divided by the number of completed responses). Additionally, different modes are better at reaching different types of respondents. As a result, researchers who really need to get results from a representative sample of their entire population will often conduct mixed-mode surveys (i.e., conducting a survey via more than one mode) to enhance the representativeness of respondents. Mixed-mode surveys reduce coverage bias (i.e., some of your population is not covered by the sampling frame) and nonresponse errors and increase response rates and the overall number of respondents. Unfortunately, they are more expensive and laborious to manage. Several studies have been conducted comparing the costs, response rates, and composition of respondents (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2009; Greenlaw & Brown-Welty, 2009; Groves, Dilman, Eltinge, & Little, 2002; Holbrook, Krosnick, & Pfent, 2007; Schonlau et al., 2004; Weisberg, 2005). One recent study (Crow, Johnson, & Hanneman, 2011) found mixed benefits in using mixed-mode surveys. Costs per complete were highest for phone ($71.78) and then for postal mail ($34.80) and cheapest for online ($9.81). They knew the demographics of their population and could conduct an analysis of nonresponse. They found that multiple modes improved the representativeness of gender in the sample but actually made the sample less representative of the citizenship and college affiliation of the overall population. At this time, it is unclear if mixed-mode surveys are worth the added cost and effort required to conduct them.

Interactivity

E-mail and paper-based surveys do not offer interactivity. The interactivity of the web provides some additional advantages.

Validation

The survey program can check each survey response for omitted answers and errors when the respondent submits it. For example, it can determine whether the respondent has left any questions blank and provide a warning or error message, limit the format of the response based on the question type (e.g., allow only numbers for questions requiring a number), and give a warning if the respondent is answering the questions too quickly.

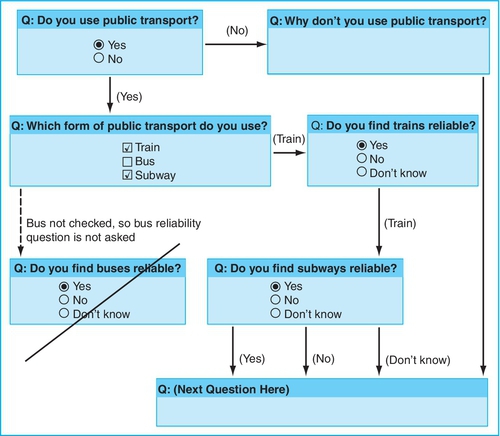

Allow for More Complex Designs

With careful design, a web-based survey can help you to make a detailed or large survey simple from the users’ point of view. Online, you have the ability to include branching questions without the respondent even being aware of the branch (see Figure 10.1).

For example, let us say that the question asks whether a participant uses public transit and the response to this question will determine the set of questions the person will be required to answer. You could choose a design where once respondents answer the question, they are required to click “Next.” When they click “Next,” they will be seamlessly brought to the next appropriate set of questions based on the response they made on the previous page. The respondents will not even see the questions for the alternative responses. This also prevents respondents from answering questions they should not based on the experience (or lack thereof).

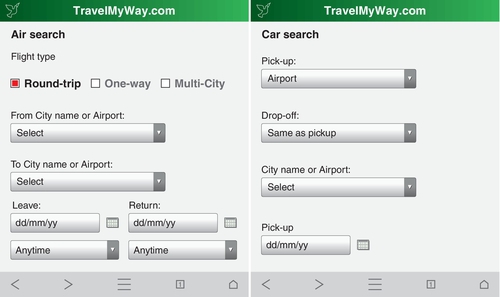

More Intuitive Design

Web widgets can help make your survey more intuitive. Widgets such as droplists can reduce the physical length of your survey and can clearly communicate the options available to the user. Radio buttons can limit respondents to one selection, rather than multiple, if required (see Figure 10.2).

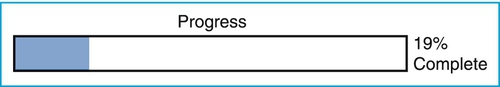

Progress Indicators

If a survey is broken into multiple pages online, progress indicators are often included to let respondents know how far along they are and how many more questions they have left to complete (see Figure 10.3). The belief is that this decreases the drop-off rate (i.e., respondents exiting the survey before completing it). However, a meta-analysis of 32 studies of medium to long length (10 minutes or more) on the effectiveness of progress indicators found that “overall, using a constant progress indicator does not significantly help reduce drop-offs and that effectiveness of the progress indicator varies depending on the speed of indicator …” (Villar, Callegaro, & Yang, 2013). If a progress indicator started off showing quick progress and then slowed down as one progressed through the survey, the drop-off rate was decreased. However, if a progress indicator started off showing slow progress and then sped up during the survey, drop-off rates increased. They also found that a constant progress indicator increased the drop-off rate when a small incentive was provided for completing the survey. From this study, we do not know if progress indicators are effective for short surveys (e.g., five minutes or less); because they are short, however, the progress indicator will move fast and is more noticeable. It is hypothesized, then, that progress indicators will be helpful.

Amount of Work for the Respondent

After completing a survey via the phone or web, respondents are done. Those completing a paper-based survey must place it in an envelope and drop it in the mail, thereby decreasing the chances of receiving completed surveys.

Data Delivery

Responses received online are much faster than with the traditional mail survey. You must incorporate the time for the survey to be returned to you via the postal system when using paper-based surveys and additional time for data entry.

Consistency

By the term “consistency,” we are referring to how the participant sees the survey. This is not an issue for paper-based surveys because you have total control over the way the questions appear. In the case of online surveys, your survey may look and behave differently depending on the device (e.g., desktop, laptop, tablet, smartphone) and browser used to open it. Ideally, you want your survey to render well regardless of device and browser. Test your survey across browsers and devices before launching to ensure the ideal user experience, or you may find lower completion rates for a portion of your sample.

Privacy

Respondents may be hesitant to complete your survey because they are concerned about their privacy. This can be manifested by lower completion rates (discussed above) and by the amount of satisficing and social desirability bias observed. This is usually not an issue for paper-based surveys since the person can remain anonymous (other than the postmark on the envelope). One study (Holbrook et al., 2003) comparing telephone to face-to-face surveys found that respondents in the telephone survey were more likely to satisfice, to express suspicion about the interview, and to demonstrate social desirability bias. Another study found more satisficing and social desirability bias in the telephone surveys than online surveys. Remember that you are ethically obligated to protect the respondents’ privacy (refer to Chapter 3, “Privacy,” page 66). Inform respondents in the beginning if the survey will be confidential or anonymous and point them to your company’s privacy policy.

Computer Expertise/Access

Obviously, computer expertise and/or access is not an issue for paper-based surveys, but it is an issue for online surveys. If your respondents have varying levels of computer experience or access to the web, this could impact your survey results. You should also determine if your survey tool is accessibility-compliant. If it cannot be completed with a screen reader or without the use of a mouse, for example, you will be excluding a segment of your population. You can increase the representativeness of your sample by conducting a multimode survey, but ideally, your tools should also be universally accessible.

Pilot Test Your Survey and Iterate

The value of running a pilot or pretesting your user research activity is discussed in Chapter 6 “Preparing for Your Activity” (refer to “Piloting Your Activity” section, page 155). However, testing your survey is so important to its success that we want to discuss the specifics here in more detail. Keep in mind that once you send the survey out the door, you will not be able to get it back to make changes—so it is critical to discover any problems before you reach the distribution stage.

You may be thinking, “Well, my survey is on the web, so I can make changes as I discover them.” Wrong. If you catch mistakes after distribution or realize that your questions are not being interpreted in the way intended, you will have to discard the previous data. You cannot compare the data before and after edits. This means that it will take more time to collect additional data points and cost more money.

When running your pilot, you want to make sure that you are recruiting people who match your user profile, not just your colleagues. Colleagues can help you catch typos and grammatical errors, but unless they are domain experts, many of the questions may not make sense to them. Using people who fit the user profile will help you confirm that your questions are clear and understandable. You will want to look for the following:

■ Typos and grammatical errors.

■ The time it takes to complete the survey (if it is too long, now is your chance to shorten it).

■ Comprehensibility of the format, instructions, and questions.

■ In the case of a web survey, determine (a) whether there are any broken links or bugs and (b) whether the data are returned in the correct or expected format.

A modified version of a technique referred to as cognitive interview testing (or cognitive pretest) is critical when piloting your survey. We say a “modified version” because formal cognitive interviewing can be quite labor-intensive. It can involve piloting a dozen or more people through iterative versions of your survey and then undertaking a detailed analysis. Unfortunately, in the world of product development, schedules do not allow for this. The key element of this technique that will benefit you in evaluating your survey is the think-aloud protocol.

Think-aloud protocol—or “verbal protocol” as it is often called—is described elsewhere in this book (refer to Chapter 7, “Using a Think-Aloud Protocol” section, page 169). If you have ever run a usability test, you are likely familiar with this technique. When applied to survey evaluation, the idea is that you watch someone complete your survey while literally thinking aloud, as you observe. As the participant reads through the questions, he or she tells you what he or she is thinking. The person’s verbal commentary will allow you to identify problems, such as questions that are not interpreted correctly or that are confusing. In addition, during the completion of the survey, you can note questions that are completed with incorrect answers, skipped questions, hesitations, or any other behaviors that indicate a potential problem understanding the survey. After the completion of the survey, you should discuss each of these potential problem areas with the pilot respondent. This is referred to as the retrospective interview. You can also follow up with the pilot respondent and ask for his or her thoughts on the survey: “Did you find it interesting?” “Would you likely fill it out if approached?” This is sure to provide some revealing insights. Do not skip the cognitive pretest or retrospective interview, no matter how pressed for time you may be! If participants do not interpret your questions correctly or are confused, the data collected will be meaningless.

After you have completed your cognitive pretesting, you will want to conduct a pilot study with a dozen or so respondents and then analyze the data exactly as you would if you were working with the final data. Obviously, this is too small of a sample to draw conclusions, but what you are checking is whether the data are all formatted correctly, there are no bugs (in the case online surveys), and you have all of the data you need to answer your research questions. Many people skip this step because it is viewed as not worth the time or effort, and stakeholders are usually anxious to get data collection started; however, once you experience a data collection error, you will never skip this step again. Save yourself the pain and do an analysis pilot!

Data Analysis and Interpretation

You have collected all of your survey responses, so what is next? Now, it is time to find out what all of those responses are telling you. You should be well prepared if you did an analysis pilot.

Initial Assessment

Your first step (if this did not happen automatically via the web) is to get the data into an electronic file. Typically, the data will be entered into a spreadsheet or .csv file. Attach to this file metadata about your survey (e.g., researcher, dates the survey was conducted, panel used, screening criteria). Having these data embedded as the first few lines of your file means that you (or researchers after you) will always know important details about how the data were collected without having to track down a separate report or presentation.

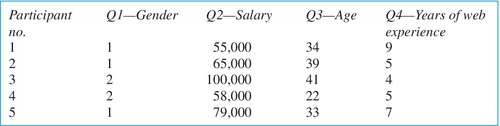

Microsoft® Excel®, SPSS, SAS, and R are some of the well-known programs that will enable you to accomplish your analyses. The rows will be used to denote each participant, and the columns will be used to indicate each question. Some statistical packages allow you to enter only numeric values, so you may need to do some coding. For example, if you asked people how they booked their most recent travel, you would not be able to enter “web,” “travel agency,” or “other” into the spreadsheet; you would have to use a code for each response, such as “web = 1,” “travel agency = 2,” and “other = 3.” Figure 10.4 illustrates a sample of data entered in a spreadsheet format. For the same reason, these tools cannot handle the text responses respondents enter for “other.” You will be able to see how many respondents chose “other,” but you will need to use a qualitative analysis tool (refer to Chapter 8, “Qualitative Analysis Tools” section, page 208) or affinity diagram (refer to Chapter 12, “Affinity Diagram” section, page 363) or to manually group the responses yourself.

Once you have your data in the spreadsheet, you should scan it to catch any abnormalities. This is manageable if you have 100 or fewer responses, but it can be more difficult once you get beyond that. Look for typos that may have been generated at your end or by the participant. For example, you might find in the age column that someone is listed as age “400,” when this is likely supposed to be “40.” Some quick descriptive statistics (e.g., mean, min/max) can often show you big errors like this. If you have the paper survey to refer to, you can go back and find out whether there was a data entry error on your part. If data entry was automatic (i.e., via the web), you cannot ethically make any changes. Unless you can contact that respondent, you cannot assume you knew what he or she meant and then change the data. You will have to drop the abnormal data point or leave it as is (your stats package will ignore any empty fields in its calculation). You may also find that some cells are missing data. If you entered your data manually, the ideal situation is to have a colleague read out the raw data to you while you check your spreadsheet. This is more reliable than “eyeballing” it, but because of time constraints, this may not be possible if you have a lot of data.

Types of Calculation

Below, we discuss the most typical forms of data analysis for closed-ended questions. You should review Section “Qualitative Analysis Tools” in Chapter 8 on page 208 for a discussion of qualitative data analysis for OEQs.

Many of the types of calculation you will carry out for most surveys are fairly straightforward, and we will describe them only briefly here. There are many introductory statistics books available today, in the event that you need more of a foundation. Our goal is not to teach you statistics, but to let you know what the common statistics are and why you might want to use them. These types of calculations can be illustrated effectively by using graphs and/or tables. Where appropriate, we have inserted some sample visuals.

Descriptive Statistics

These measures describe the sample in your population. They are the key calculations that will be of importance to you for closed-ended questions and can easily be calculated by any basic statistics program or spreadsheet.

Central Tendency

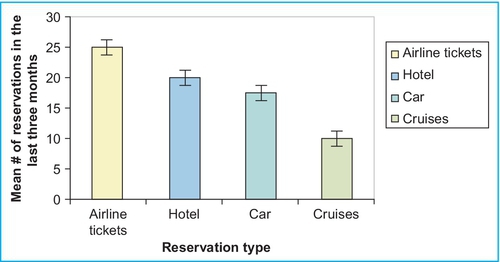

■ Mean: Average of the scores in the population. It equals the sum of the scores divided by the number of scores. See Figure 10.5.

■ Median: The point that divides the distribution of scores in half. Numerically, half of the scores in your sample will have values that are equal to or larger than the median, and half will have values that are equal to or smaller than the median. This is the best indicator of the “typical case” when your data are skewed.

■ Mode: The score in the population that occurs most frequently. The mode is not the frequency of the most numerous score. It is the value of that score itself. The mode is the best indicator of the “typical case” when the data are extremely skewed to one side or the other.

■ Maximum and minimum: The maximum indicates how far the data extend in the upper direction, while the minimum shows how far the data extend in the lower direction. In other words, the minimum is the smallest number in your data set and the maximum is the largest.

Measures of Dispersion

These statistics show you the “spread” or dispersion of the data around the mean.

■ Range: The maximum value minus the minimum value. It indicates the spread between the two extremes.

■ Standard deviation: A measure of the deviation from the mean. The larger the standard deviation, the more varied the responses were that participants gave.

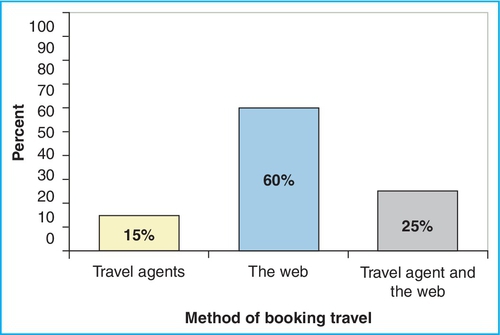

■ Frequency: The number of times that each response is chosen. This is one of the more useful calculations for survey analysis. This kind of information can be used to create graphs that clearly illustrate your findings. It is nice to convert the frequencies to percentages (see Figure 10.6).

Measures of Association

Measures of association allow you to identify the relationship between two survey variables.

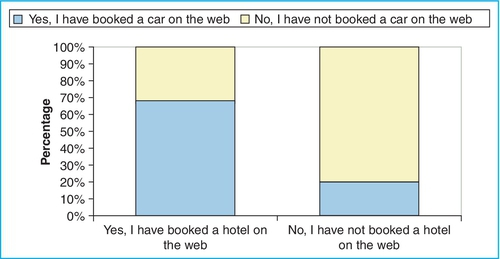

■ Comparisons: Comparisons demonstrate how answers to one question are related to the responses to another question in order to see relationships. For example, let us say we had a question that asked people whether they made hotel reservations via the web. Imagine 73% had and 27% had not. As a comparison, we want to see whether the answer to this question relates to whether or not they book cars on the web. So, of the 73% that have booked a hotel online, how many of them have also booked a car online? This is an example of a cross tabulation. You can graph it to see the relationships more clearly (see Figure 10.7). Pivot tables are one way to conduct this analysis.

■ Correlations: They are used to measure the degree to which two variables are related. It is important to note that correlations do not imply causation (i.e., you could not state that the presence of hotel deals caused people to book a hotel). Correlation analysis generates a correlation coefficient, which is the measure of how the two variables move together. This value ranges from 0 (indicating no relationship) to ± 1. A positive number indicates a positive correlation, and the closer that number is to 1, the stronger the positive correlation. A “positive correlation” means that the two variables move in the same direction together, while a “negative correlation” means that the two variables move in the opposite direction.

Inferential Statistics

Like the name implies, these measures allow us to make inferences or predictions about the characteristics of our population. We first need to test how generalizable these findings are to the larger population, and to do that, we need to do tests of significance (i.e., confirming that these findings were not the result of random chance or errors in sampling). This is accomplished via T-tests, Chi-squared, and ANOVA, for instance. Other inferential statistics include factor analysis and regression analysis, just to name a few. Using our TravelMyWay.com example, let us imagine your company is trying to decide whether or not to do away with the live chat feature. If you conducted a survey to inform your decision, you would likely want to know if the use of the live chat feature is significantly correlated with other measures like satisfaction and willingness to use the service in the future. To answer this question, inferential statistics will be required. Refer to the “Suggested Resources” if you would like to find a book to learn more about this type of analysis.

Paradata Analysis

Paradata is the information about the process of responding to the survey. This includes things like how long it took the respondent to answer each question or the whole survey, if he or she changed any answers to his or her questions or went back to previous pages, if the respondent opened and closed the survey without completing it (i.e., partial completion), and how he or she completed it (e.g., smartphone app, web browser, phone, paper). It can be enlightening to examine these data to see if your survey is too long and confusing, if there are issues completing your survey via one of the modes (e.g., respondents that started the survey on a smartphone or tablet never submitted), or if you have a set of respondents that are flying through your survey far too quickly. It is unlikely you can collect much of these data for phone or paper surveys, but you can via some web survey tools and vendors.

Communicating the Findings

As fascinating as you might find all of the detailed analyses of your survey, it is unlikely that your stakeholders will be equally fascinated by the minutia. You cannot present a 60-slide presentation to your stakeholders covering all of your analyses, so you really need to pick a few critical findings that tell a story. Once you have identified what those few critical findings are, you can begin to create your presentation (e.g., report, slides, poster, handouts).

An important thing to keep in mind when presenting survey results is to make them as visual as possible. You want those reviewing the findings to be able to see the findings at a glance. Bar charts and line graphs are the most effective ways to do this. Most statistics packages or Microsoft Excel will enable you to create these visuals with ease.

Obviously, you will need to explain what the results mean in terms of the study objectives and any limitations in the data. If the results were inconclusive, highly varied, or not representative of the true user population, state this clearly. It would be irresponsible to allow people to draw conclusions from results that were inaccurate. For example, if you know your sample was biased because you learned that the product team was sending only their best customers the link to your survey, inform the stakeholders that the data can be applied only to the most experienced customers. It is your responsibility to understand who the survey is representing and what conclusions can be drawn from the results. Sometimes, the answer is “further investigation is needed.”

Pulling It All Together

In this chapter, we have illustrated the details of creating an effective survey. You should now be able to create valuable questions and format your survey in a way that is easy to understand and that attracts the interest of the potential respondents. You should also be equipped to deploy your survey, collect the responses, and analyze and present the data. You are now ready to hit the ground running to create a survey that will allow you to collect the user research you need.

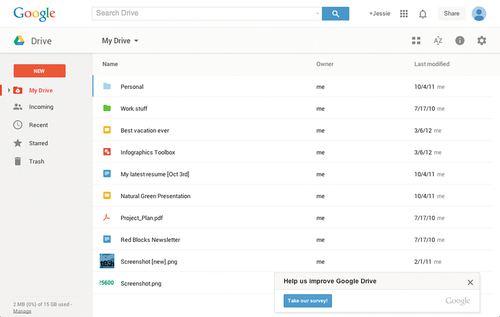

By inviting users to the survey as they are using the product, HaTS yields timely metrics and insights. HaTS applies best practices in sampling and questionnaire design, informed by decades of academic research, to optimize data validity and reliability. HaTS also uses consistent sampling and standardized results reporting to enhance its scalability. Launched in 2006, HaTS has expanded to many of Google’s products, including Google Search, Gmail, Google Maps, Google Docs, Google Drive, and YouTube. Surveys now play an important role as a user-centric method to inform product decisions and measure progress toward goals.

In the remainder of this case study, we will take a closer look at how we use HaTS for the Google Drive product, discussing its approach to sampling and respondent invitation, the questionnaire instrument, and some of the insights it has provided to the team.

Sampling and Invitation

The essence of surveying is sampling, a way to gather information about a population by obtaining data from a subset of that population. Depending on the population size and the number of survey respondents, we can estimate metrics at a certain level of precision and confidence. HaTS uses a probability-based sampling approach, randomly selecting users to see a survey invitation.

Each week, we invite a representative set of Google Drive’s users to take HaTS. An algorithm randomly segments the entire user base into distinct buckets. Each bucket may see the survey invitation for a week; then, the invitation rotates to the next bucket. Randomizing based on individual users, instead of page views (e.g., choosing every nth visitor), reduces bias toward users that visit the product more frequently. To avoid effects of survey fatigue, users shown an invitation to HaTS are not invited again for at least 12 weeks. The target sample size (i.e., the number of survey completions) depends on the level of precision needed for reliable estimates and comparisons. For Google Drive’s HaTS, as commonly used for such research, we aim for at least 384 responses per week, which translates to a ± 5% margin of error with 95% confidence.

One of the fundamental strengths of HaTS is that people are invited to the survey as they are using the product itself; therefore, the responses directly reflect users’ attitudes and perceptions in context of their actual experiences with the product. We invite potential respondents through a small dialog shown at the bottom of the product page (see Figure 10.8). The invitation is visually differentiated from other content on the page and positioned so that it is easily seen when the page loads. Note that HaTS does not use pop-up invitations requiring users to respond before they can continue to the rest of the site, as that would interrupt users’ normal workflows. The invitation text is “Help us improve Google Drive” with a “Take our survey!” call to action; this neutral wording encourages all users equally, not only those with especially positive or negative feedback.

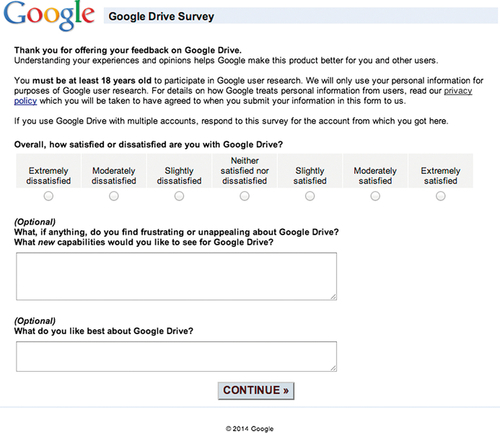

Questionnaire Instrument

We designed the HaTS questionnaire following established guidelines to optimize the reliability and validity of responses (Müller, Sedley, & Ferrall-Nunge, 2014). HaTS minimizes common biases such as satisficing (Krosnick, 1991; Krosnick, Narayan, & Smith, 1996; Krosnick, 1999), acquiescence (Smith, 1967; Saris et al., 2010), social desirability (Schlenker & Weigold, 1989), and order effects (Landon, 1971; Tourangeau et al., 2004). It also relies on an extensive body of research regarding the structure of scales and responses options (Krosnick & Fabrigar, 1997). We optimized the visual design of the HaTS questionnaire for usability and avoid unnecessary and biasing visual stimuli (Couper, 2008).

The core of Google Drive’s HaTS lies in measuring users’ overall attitudes over time, by tracking satisfaction. We collect satisfaction ratings by asking, “Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with Google Drive?” (see Figure 10.9) referring to the concept of satisfaction in a neutral way by calling out both “satisfied” and “dissatisfied.” As satisfaction is a bipolar construct and we have sufficient space in the user interface, a 7-point scale is used to optimize validity and reliability, while minimizing the respondents’ efforts (Krosnick & Fabrigar, 1997; Krosnick & Tahk, 2008). The scale is fully-labeled without using numbers to ensure respondents consistently interpret the answer options (Krosnick & Presser, 2010). Scale items are displayed horizontally to minimize order biases and are equally spaced (Tourangeau, 1984), both semantically and visually (Couper, 2008): “Extremely dissatisfied,” “Moderately dissatisfied,” “Slightly dissatisfied,” “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” “Slightly satisfied,” “Moderately satisfied,” and “Extremely satisfied.” Note the use of “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied” instead of “Neutral” as the midpoint, which reduces satisficing (Krosnick, 1991). Furthermore, the negative extreme is listed first to allow for a more natural mapping to how respondents interpret bipolar constructs (Tourangeau et al., 2004). The satisfaction question is the only required question within HaTS, since without a response to this question, the primary goal of HaTS is not achieved.

Another critical goal of ours for Google Drive’s HaTS is to gather qualitative data about users’ experiences. Through two OEQs (see Figure 10.9), we ask respondents to describe the most frustrating aspects of the product (“What, if anything, do you find frustrating or unappealing about Google Drive?” and “What new capabilities would you like to see for Google Drive?”) and what they like the most about the product (“What do you like best about Google Drive?”). Even though the former question may appear as double-barreled in its current design, through experimentation, we determined that asking about experienced frustrations and new capabilities in the same question increased the response quantity (i.e., a higher percentage of respondents provided input) and quality (i.e., responses were more thoughtful in their description and provided additional details) and also reduced analysis efforts. Respondents are encouraged to spend more time on the frustrations questions since they are listed first, and their answer text field is larger (Couper, 2008). These questions are explicitly labeled as “(Optional),” ensuring that respondents do not quit the survey if they perceive an open-ended response as too much effort and minimizing random responses (e.g., “asdf”) that slow down the analysis process. We have consistently received response rates between 40% and 60% for these OEQs when applying this format.

Even though this case study only concentrates on HaTS’ first-page questions about the respondent’s overall attitudes and experiences with the product, the HaTS questionnaire contains further pages. On the second page, we explore common attributes and product-specific tasks; on the third page, we ask about some of the respondent’s characteristics; and we reserve the fourth and last page for more ad hoc questions.

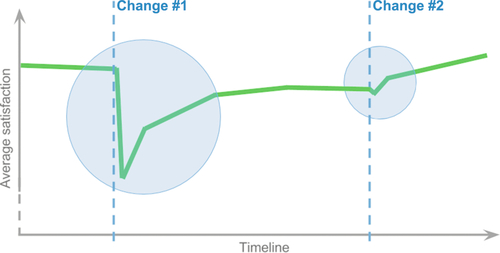

Applications and Insights