CHAPTER 6

The Chapter You’ll Love to Hate

Politics!

There. Are you angry yet?

Nothing makes folks touchy quite like politics. Few humans lack strong political opinions. Partisans love their side, hate the other. Centrists hate extremists of both sides while caring little for ideology. The far left and far right think the center-left and center-right are wishy-washy weaklings. And they’re all surely, confidently, right. It’s a battle for America’s heart and soul, and we aren’t supposed to bring it up before dessert.

But we’re friends now, so here we go. Politics are charged, but they matter for stocks. Nasty laws and regulations have caused or worsened bear markets. Seemingly tiny rule changes can disrupt entire industries and capital markets. Widespread myths about ideology and partisan rhetoric can give contrarians big opportunities to game the crowd.

We’ll cover all of this and more in these pages. Warning, you might not like it. If you lean one way or the other—doesn’t matter which way—your instinct will be to hate at least 50% of this chapter. Just human nature! Battling this instinct is step one. Whether liberal or conservative you’re far from alone, and your ideology is surely priced always. That’s very hard for most people to swallow.

To help spare your sanity, we’ll stay away from pure sociopolitical factors. I don’t do sociology. That’s for someone else. As I mentioned in Chapter 4, it is fine and dandy to think and have opinions about these. They impact everyday life! But they’re out of the investing realm. Markets focus narrowly. Stocks don’t care who your neighbor Bob marries and whether they replace the champagne toast with ceremonial pot smoking at the reception. Stocks care how rules and regulations impact the flow of capital and resources, profits, foreign trade and the ease and cost of commerce—and whether that’s already priced or not and really only over the next approximate 30 months or so. Narrow variables, and easy to isolate if you know what to look for and can train your brain to be objective.

You might already be skeptical. That’s ok! I won’t cry if you skip to Chapter 7. But I hope you don’t, because this chapter has some prime contrarian tricks and powerful elephants in the room. Here’s the menu:

- How to clear your brain of bias, one of investing’s deadliest traps

- The biggest elephant in the political living room—and not the one on the Republican Party’s logo

- When new laws matter … and when they don’t

- Why Congress isn’t always stocks’ biggest political enemy

Step 1: Ditch Your Biases

Presidents, prime ministers, governors, senators, members of Congress, members of parliament, military dictators, fascist thug dictators and commie thug dictators have one thing in common: They’re politicians. Experts at self-promotion and marketing. Big-time elected politicians run on focus-group-tested platforms. Dictators survive on manufactured cult of personality. In and out of democracies, political life is one big ad campaign.

There are exceptions, perhaps. Maybe some wanna-be Mr. Smith went to Washington with ideals and values. Life can imitate Frank Capra films. But most high-ranking politicians are megalomaniacs with a high incidence of observed psychopathic traits. I didn’t make that up—several psychological studies show it, including one from the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 2012.1 Life imitates The Onion, too: “Nation Tunes In to See Which Sociopath More Likable This Time,” which skewered the 2012 Presidential debates, wasn’t entirely satire.2

My point isn’t that all politicians are evil. If you like a politician or two, be my guest! Have opinions! Again, societal and political issues are important, interesting and fine to think about. Education, foreign policy, civil liberties and all the rest matter. It is natural and great to have strong opinions in these areas. But markets don’t care about ideology. So when you’re thinking about markets, turning off your opinions is best. Political bias blinds.

The easiest way to turn off bias, in my experience, is to make “he’s just a politician” or “she’s just a politician” your mantra. If you find yourself believing Presidential candidate John or Jane Chowderhead will be wonderful or terrible for stocks based on speeches, debates and campaign ads, remind yourself: “Just a politician.” They’re in marketing mode. Their goal is to pique your emotions. When investing, you want to turn off your emotions.

The more you remember they’re all politicians, the easier it is to objectively assess how politics impact stocks. Politics matter! But not in a “Party X is good for stocks and Party Y is bad” kind of way. Or in a “Party Y is good for stocks and Party X is bad” way, lest you think I’m an anti-Y-ist. “Y,” you might ask? Because “Y” and “X” are always priced. Stocks care more about actual laws, rules and regulations. Policies’ seen and unseen consequences. Get past your opinions, and reality is easier to see.

My Guy Is Best, Your Guy Is Worst and Other Unhelpful Opinions

Investing on opinions is folly, but many folks do it. Talking heads and op-ed pages encourage us. Many state their beliefs as fact, with ideology and cherry-picked factoids as evidence. Fine for them—they’re pundits, not analysts! Their job is to be opinionated and attract eyeballs. But most don’t provide usable facts for you, the cool-headed contrarian.

Markets discount this quickly. Political opinions are everywhere! All over TV, your newspaper, the Internet, your office, your neighbor’s dinner table—widely discussed and therefore pre-priced. A lot of it conflicts! One paper could call a candidate with big spending plans a welfare state-loving socialist nightmare. Another could call him a pro-growth dream who will turn the underprivileged into employable human capital and bring jobs to our underemployed youth. One cable pundit could call a tax-cutting supply-side reformer the market’s knight in shining armor. Another could call him the austerity-obsessed first horseman of the apocalypse.

Same goes for new laws. Take the Affordable Care Act (ACA), or “Obamacare” if you prefer. A Google search for “Obamacare op-ed” returns over a million hits. Over one million published opinions on whether the law is wonderful or a disaster. Some love it. Others loathe it. For hundreds or more different reasons. And they’re all just fine opinions.

Opinions are not facts. Facts are solid. Irrefutable. Feelings are squishy, fungible and differ from person to person. For everyone who hates a politician, party or law, someone else loves them. For every person who thinks tax hikes kill consumption, another thinks they’re deficit-reduction magic that help fund the solutions we need to help consumers.

Markets reflect all these emotions. The sheer volume of political noise in our media, combined with the fact we have over 146 million registered American voters,3 makes it impossible for the opinion of “manyone” not to be priced in. However strongly you feel about a President, a candidate, the party controlling Congress or a new law, there is little or nothing in your opinion that someone else doesn’t already know. You’re unlikely to be “anyone” and likely to be “manyone” in political sociology unless your views are shared by almost no one. Part of a big crowd, fully priced.

Stocks are politically agnostic—they don’t care which party is in power. Bear markets begin and end on both parties’ watch, as Table 6.1 shows. Neither is inherently good or bad for markets.

Table 6.1 S&P 500 Bear Markets and Presidential Party

| Start | President | End | President |

| 9/6/1929 | Hoover [R] | 6/1/1932 | Hoover [R] |

| 3/10/1937 | FDR [D] | 4/28/1942 | FDR [D] |

| 5/30/1946 | Truman [D] | 6/13/1949 | Truman [D] |

| 8/2/1956 | Eisenhower [R] | 10/22/1957 | Eisenhower [R] |

| 12/12/1961 | Kennedy [D] | 6/26/1962 | Kennedy [D] |

| 2/9/1966 | Johnson [D] | 10/7/1966 | Johnson [D] |

| 11/29/1968 | Johnson [D] | 5/26/1970 | Nixon [R] |

| 1/11/1973 | Nixon [R] | 10/3/1974 | Ford [R] |

| 11/28/1980 | Carter [D] | 8/12/1982 | Reagan [R] |

| 8/25/1987 | Reagan [R] | 12/4/1987 | Reagan [R] |

| 7/16/1990 | Bush [R] | 10/11/1990 | Bush [R] |

| 3/24/2000 | Clinton [D] | 10/9/2002 | GW Bush [R] |

| 10/9/2007 | GW Bush [R] | 3/9/2009 | Obama [D] |

Source: FactSet, as of 12/2/2014. S&P 500 bear markets, 1929–2014.

Opinions can influence sentiment, but this gets baked in during campaign season. The likelier a candidate appears to win, the more investors vote their feelings and opinions about him or her, and this shows up in prices. If you wake up the day after the election and decide to buy or sell based on how you feel about who won, you’re too late.

I wrote about this in my 2010 book, Debunkery—I called it the “Perverse Inverse.” There, I explained that about two-thirds of American investors lean Republican and see the GOP as pro-business—forgetting they’re just politicians. They believe the campaign marketing spin. They also forget Democrats are just politicians, believing all their campaign marketing spin about social fairness and big government. They see Democrats as anti-business wealth redistributors. Two strong opinions! These are usually baked into election-year returns. In election years when the Presidency flips from red to blue, stocks tend to render below-average returns—and fall further if Congress flips, too. When the White House flips to the GOP, stocks average positive, and rise even higher if Congress follows.

But when the new President is in office, stocks U-turn! Stocks are historically up big in Democrats’ inauguration years. Even bigger if Congress went blue, too. But they’re down in Republicans’ first years. Table 6.2 has the numbers, straight from Debunkery.

Table 6.2 Party Changes and S&P 500 Performance

| Election Year | Inauguration Year | |

| Presidency changed from Republican to Democrat | –2.8% | 21.8% |

| Presidency changed from Democrat to Republican | 13.2% | –6.6% |

| Presidency and Congress changed from Democrat to Republican | –8.9% | 52.9% |

| Presidency and Congress changed from Republican to Democrat | 25.5% | –3.0% |

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc. S&P 500 Total Return, 12/31/1925–12/31/2009.

Why? They’re all just politicians! The Democrats aren’t really so anti-business as feared. Republicans aren’t as pro-business as hoped. What was priced in—hopes and fears—in this realm tend to be heartfelt and extreme. These people won a popularity contest to get their job. Their main goal? Staying well-liked for the re-election campaign. Following campaign pledges to a T would alienate almost half the population. The pledges folks love or hate usually get watered down or shelved. All those strong opinions don’t matter on a forward-looking basis.

Opinions are feelings about what a politician has done or might do. Stocks can swing on this sentiment in the short term, but you can’t time investing decisions around it—too many other variables. Your best bet, when thinking politically, is to look at the will-do. What will actually become law? What is the likeliest impact on commerce, trade, banking and markets?

A Magical Elephant Named Gridlock

Deep political analysis is hard work—identifying unseen consequences and avoiding the broken window fallacy takes imagination and go-it-alone chutzpah. We’ll get there later. First, we’ll hit the highest, easiest level.

In competitive, developed countries like America, markets hate active legislatures. Stocks know the status quo. They know the rules and how to navigate them. Change requires adaptation. It also creates winners and losers, which markets hate. If Congress can’t do anything, they can’t screw anything up—a huge relief for stocks.

The more laws Congress passes, the higher the chance they could redraw property rights, rewrite regulation or redistribute wealth, resources and opportunity—all negative. Prospect theory—folks’ tendency to feel the pain of loss more than the joy of an equivalent gain—is big in behavioral finance, as we’ll see in Chapter 9, but it applies to legislation too. If a new law shifts resources from Group A to Group B, Group A hates it more than Group B loves it. Their net negativity can weigh on stocks. The more active Congress is, the more risk averse markets get. Political risk aversion spills psychologically to market risk aversion.

So to see how politics will impact stocks, first ask: What’s the likelihood these greasy politicians pass something radical? Low or high?

This is easy and basic, but few look there. Here, too, feelings get in the way. We have plenty of evidence markets love gridlock. As I showed in my 2006 book, The Only Three Questions That Count, years three and four of a President’s term have the highest average returns, and gridlock is why. Presidents usually lose power in midterms. They know it, so they front-load big moves into years one and two. Obama did it with the ACA and Dodd-Frank. Bush did it with Sarbanes-Oxley. Clinton did it with tax hikes and attempts at health care reform. Late-term changes like 1999’s Gramm-Leach-Bliley are rare.

Markets love gridlock, but people hate it. As people, we hate polarization and bickering do-nothing Congresses. The rancor is annoying. We voted for these clowns so they could fix whatever we think needs fixing, not so they could squabble and sit on their hands. The fewer laws Congress passes, the lower their approval ratings sink. In 2013, Congress passed a record-low 72 measures.4 That November, Congress’s approval rating hit a record-low 9%.5 They were only nine percentage points more popular than Ebola! But the S&P 500 finished up 32.4%.6 Voters’ broad dissatisfaction with Washington blinds folks—they don’t appreciate the fact gridlock blocks new laws potentially spooking stocks. Partisans want their party’s proposals to pass. Independent-minded folks want bipartisan compromise and less bickering. Few believe doing nothing is best or even ok—because they too much believe their own ideology. Liberals hate nothing happening because they want what they want. Conservatives too. Non-ideologists too. Only markets like it because when political risk aversion falls, risk aversion falls.

Bipartisan compromise might sound nice. It implies watered-down, middle-of-the-road laws. But history has some big bipartisan stinkers, like Sarbanes-Oxley. The devastating Tariff Act of 1930—Smoot-Hawley—enjoyed broad bipartisan support. So did the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, aka the Jones Act, which bottlenecks US crude oil transportation even today. The Humphrey-Hawkins Act of 1978 was another bipartisan bomb. It created the Fed’s dual mandate, tying US monetary policy to the long-ago debunked belief that inflation and unemployment are linked. Bipartisan doesn’t mean good. It means popular.

Great as gridlock is, few fathom its market benefits. Gridlock is the elephant in the room! Markets thrive on gridlock, but not because a magic gridlock switch flips in investors’ minds. It is more of a non-realization realization that radical new laws aren’t passing. The absence of a negative is a positive. Everyone sees gridlock. Most just can’t see that doing nothing does a lot for stocks.

(Not) Just a Bill Sittin’ on Capitol Hill

Not every fundamentally negative new law mangles markets. Stocks hate quick, radical change—having to adapt and discover winners and losers real-time. The negative surprise potential is huge. The more time markets have to discover and digest potential negatives (or positives), the more muted the impact tends to be—stocks vet out potential surprises early, sapping their power. They can still hurt or help, but less.

Markets start digesting new laws when the proposal enters public conversation. The initial discussion, draft legislation, multiple rounds of Congressional debate and amendments—and all the media chatter—let markets price the wide-ranging opinions and likely outcomes. Every pundit who discovers a potential winner or loser does stocks a favor, letting them discount the potential fallout. When you know something bad is coming, and you can brace for it, it is easier to deal with than a surprise.

The longer the discovery period, the less jarring the actual law’s impact tends to be. Conversely, short discovery periods can bite hard.

Consider stocks’ reaction to one of recent history’s worst laws: The “Act to protect investors by improving the accuracy and reliability of corporate disclosures made pursuant to the securities laws, and for other purposes,” better known as Sarbanes-Oxley or Sarbox. The name sounds great, but it was Congress’s overreaction to the Enron accounting scandal. Sarbox tried to improve corporate governance and transparency by doing things like making CEOs criminally liable for accounting and reporting errors. A huge, costly burden on publicly traded companies. Nasty stuff!

Sarbox moved fast. The draft bill was introduced February 14, 2002, after about six weeks of Senate hearings on Enron and other perceived ills of corporate America. House committee debate lasted two months—short by DC standards. The final version hit the full House April 16 and passed April 24. The Senate passed its stricter version July 15. Congress set out to reconcile the two bills July 24 and 25. Most observers thought the softer House version would win the day and become law. Yet largely due to a last-minute sticky situation involving President Bush and personal loans from corporations to board members, he suddenly shifted his support to the Senate version, the law we have today. And, with the WorldCom scandal breaking during the legislative process, most provisions were given more teeth behind closed doors. President Bush signed the law July 30, and it took effect that day. No phase-in—just boom! Let there be rules!

Stocks were already in a bear market, but Sarbox likely made it much worse. Between April 16 and July 25, the S&P 500 fell –25.4%.9 The bear market lasted another two and a half months. But a bull market began October 9—even though Sarbox was big and bad, cyclical factors overruled it. The existence of big rules doesn’t keep stocks from rising. Markets can adapt, and they adapted to Sarbox. The initial shock hurts markets. Then life goes on.

Few fathomed this when Congress passed another sweeping overhaul, the ACA. The ACA isn’t as fundamentally negative as Sarbox. Sarbox hamstrung all of corporate America! The ACA was big, but tamer—it created winners and losers in health care, and incrementally raised investment taxes and businesses’ costs. But many investors saw it as the devil, half a step from socialism. When it passed in March 2010, folks feared it would sink stocks. Fears resurged repeatedly for years. Yet, as much as folks hated the law, stocks did fine. Why? It was priced!

As I said before, stocks start discounting laws when people start discussing them. ACA entered the national conversation way back in 2008’s Presidential campaign. Not as the ACA! But John McCain and Barack Obama both promised big health care reform. After Obama won, markets knew they’d get his version. He outsourced it to Congress, which spent over a year writing, debating, rewriting and neutering the legislation. It passed on a Sunday, March 21, 2010. Stocks rose the next day. A correction ran from April 15 to July 5, but that had much more to do with fears Greece would collapse and take the euro down with it. Health Care stocks didn’t do great in 2010—they underperformed through early 2011—but that’s normal when a law radically alters an industry’s foundation. Some segments of Health Care, like managed care facilities, had to overhaul their business models. Just normal. Health Care stocks still rose! Just less than the overall market.

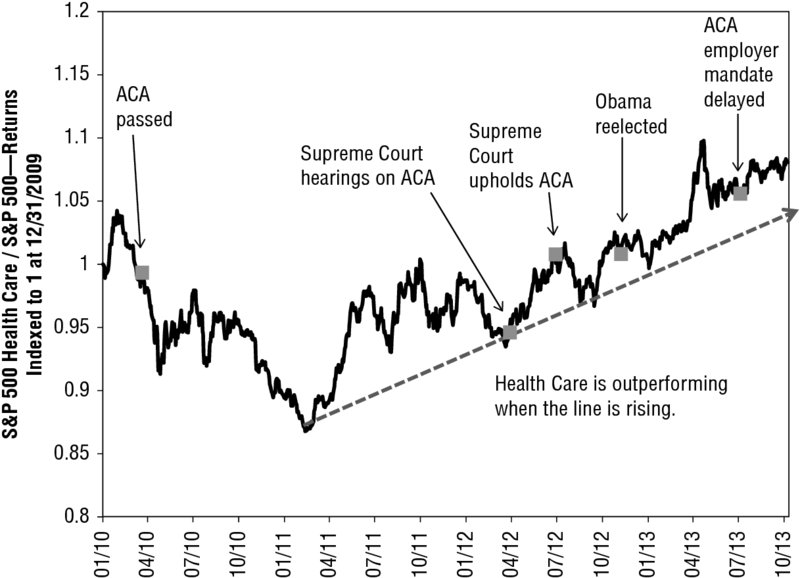

ACA fears resurged repeatedly for four years, but stocks fared well. Markets rose amid the early 2012 Supreme Court arguments and in the run-up to the decision. The Court affirmed most of the ACA’s constitutionality on June 28, 2012. Stocks marched higher. The 2012 Presidential election was widely seen as a referendum on the ACA, and Obama’s victory the law’s final affirmation. Stocks fell a bit the two weeks after the election, then turned higher—and Health Care outperformed. In July 2013, when Obama delayed the hotly contested employer mandate for one year, stocks yawned—not what you’d expect if the delay were wildly bullish (or bearish, depending on your viewpoint). When folks found out they couldn’t keep their plans, contrary to Obama’s promises, their anger didn’t sink stocks. Neither did the investment income tax tweaks that took effect in 2013. Markets rose throughout the botched rollout in late 2013 and early 2014. All these negatives were priced. And here is the kicker: From early 2011 on, throughout all the eyeball-grabbing events above, US Health Care stocks beat the S&P 500 (Figure 6.1). And why? Maybe it was because the ACA was much smaller than originally feared—a point still today few have noticed.

Figure 6.1 S&P 500 Health Care Versus S&P 500

Source: FactSet, as of 10/9/2013. S&P 500 Health Care and S&P 500 Total Returns, 12/31/2009–10/8/2013. Indexed to 1 on 12/31/2009.

During the 2008 Presidential campaign, there were 44.7 million uninsured people, 14.9% of the population.10 Obama claimed his health care reform plan would insure about 35 million of them. Well, one year in, he overshot. Most sources estimate that the net reduction in the nominal uninsured population from 2013 is between 7 and 10 million, but this is somewhat skewed by population growth. Private and government estimates both show the percentage of uninsured folks in 2014 declining to levels a bit below 2008. Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) put it at 13.1%; Gallup polls say 13.4%.11 Either way, that 35 million increase didn’t happen.

Why is this important? With the ACA, folks first feared and priced the cost of subsidizing insurance for 35 million folks, and markets couldn’t quickly discover the likelihood of sky-high costs. As Nancy Pelosi infamously quipped, Congress had to pass the ACA for anyone (including them) to find out what was in it. Markets initially digested that much bigger outcome, then gradually came to realize the ACA wouldn’t work as intended. In the end, it cost about 10% to 15% of what folks initially assumed, for a 10% to 15% increase in the insured population. There are mountains and there are molehills.

In the end, we went through all this rigmarole for a few million folks who weren’t insured before but are now—maybe 1.1% of the total US population.12 If someone had said in 2008 that insurance premiums would rise 4% to cover 1.1% of the population, the world might have looked at it differently. If someone says, we’re creating a new program for 35 million people, that’s huge! For 3.5 million, it’s much smaller. Markets would have known the ACA wouldn’t bring down the broader world the way people feared it would. Instead of massive subsidies to cover 10% of the population, we’re talking about 1%. For the 99%, the piece of the cost to cover the 1% is much lower. This smaller-than-expected outcome gave markets relief. I think. Maybe I’m wrong.

There was an elephant in the ACA, but it wasn’t market-related. In all the hubbub, folks forgot Obama’s goal was to take 45 million uninsured down to 10 million. Very few realize that for all the cost, hassle and aggressive marketing, coverage improved just modestly—evidence government programs don’t work. That’s the elephant. In this day and age, and few fathom this, it is nearly impossible for the government to “do” much. Too much arteriosclerosis.

The ACA’s ultimate fecklessness stared us in the face from day one. Think of it this way: Wal-Mart’s global empire wasn’t built in a day—Sam Walton started small, with one store in Arkansas in 1950. It took decades of trial and error and organic growth to build an efficient, massive marketplace. If it took a genius businessman like Walton decades, how could the government implement the massive infrastructure of the ACA in three years without a hitch? The outcome was always going to be huge up-front cost, clunky rollout and limited benefits.

Markets don’t care about this, though. The government has spent inefficiently since about always—no shock factor. And the bill didn’t sink us—like we chronicled in Chapter 4, we don’t have a debt problem. Not a market risk—just a political problem and more fodder in the big versus small government debate. And one that will likely come back as the liberals who championed the ACA find out there are still over 40 million uninsured folks—the people they wanted to help weren’t helped so much. The universal health care debate will return, whether in 10 years, 15 years or whenever. Some other group will cook up some new scheme, saying Obama was too timid and didn’t do it right. Maybe they’ll try to tax the wealthy to create a Social Security–like trust for 25-year-old meth heads who can’t otherwise snort insurance. Who knows—and not in the next 30 months! But it won’t end. The king is dead, long live the king.

That Which Is Seen and That Which Is Unseen

The ACA had huge unintended consequences, but they weren’t as huge as expected and were too minor and too well-known to matter to stocks. The ACA misaligned the incentives to own health insurance. Since the law raised insurance firms’ regulatory costs, premiums went up. For many businesses, it was cheaper to pay the fine than comply with the mandate. Many provided health benefits anyway—great for recruiting and retaining workers! But others cut their plans, shunting consumers to the state and national health exchanges. Some folks bought insurance, but others realized there, too, the penalty was cheaper than premiums. With the ban on pre-existing conditions gone, healthy folks could just pay the fine, pay for basic doctor’s visits out of pocket, and wait to buy health insurance until they needed something major. Unintended, but not unseen.

What really rankles stocks are the unintended consequences few see—Bastiat’s shoemaker missing out on a six-franc sale because the shopkeeper’s son broke a window. Downstream unintended consequences that will catch folks by surprise.

These can rear their ugly heads years after the law is passed—this is when “not in the next 30 months” meets “now.” Take Sarbox again. As we explored in Chapter 1, 2008’s panic happened because hyper-aggressive asset write-downs wiped about ![]() 2 trillion from America’s banking systems. The mark-to-market accounting rule was the direct culprit—a secondary regulatory change, not Congress’s handiwork (perhaps more dangerous, which we’ll get to shortly). But you have to wonder, would banks have slashed their balance sheets so ruthlessly if CEOs and CFOs weren’t criminally and civilly liable for bogus accounting as defined in Sarbox? Without the threat of jail time, would write-downs have dwarfed the roughly

2 trillion from America’s banking systems. The mark-to-market accounting rule was the direct culprit—a secondary regulatory change, not Congress’s handiwork (perhaps more dangerous, which we’ll get to shortly). But you have to wonder, would banks have slashed their balance sheets so ruthlessly if CEOs and CFOs weren’t criminally and civilly liable for bogus accounting as defined in Sarbox? Without the threat of jail time, would write-downs have dwarfed the roughly ![]() 300 billion in actual loan losses?13 Consider: In 1990, then Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan wrote a letter to Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Commissioner Richard Breeden suggesting that mark-to-market accounting for illiquid bank loans was wrongheaded because bankers could get aggressive with valuing assets with no ready market, based on sheer irrationality. He couldn’t know it then, but post-Sarbox, the incentives flipped.

300 billion in actual loan losses?13 Consider: In 1990, then Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan wrote a letter to Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Commissioner Richard Breeden suggesting that mark-to-market accounting for illiquid bank loans was wrongheaded because bankers could get aggressive with valuing assets with no ready market, based on sheer irrationality. He couldn’t know it then, but post-Sarbox, the incentives flipped.

Sarbox played out in a way no one—at least no one publicly documented beforehand—saw coming. Seeing these things takes imagination. It also requires you to go against the grain and move past the chatter—true contrarian stuff. When it comes to laws, the crowd focuses on the immediate seen consequences. Will the ACA whack growth? Will tax hikes hit spending? These are fine questions, but they’re often too widely discussed to matter to stocks. The trick is training your brain to imagine what others can’t.

Here’s an example. Europe’s parliament just cracked down on bankers’ bonuses. They decided bankers’ exorbitant bonuses caused the financial crisis by encouraging risky behavior that brought down the entire system. Wrongheaded, but politicians always need a scapegoat, and bankers are an easy target. No one ever told small children bedtime stories aimed at encouraging them to grow up to be bankers. So they passed a rule capping bonuses at 100% of annual salary—200% if shareholders approve. They believe this will crisis-proof their system because bankers will no longer have a monetary incentive to make risky bets.

This is wrong, obviously—crisis-proof is a fairy tale. Worse, it introduces negatives. Some get plenty of headlines. Britain filed a lawsuit with Europe’s top court arguing the cap would hollow out London’s banking sector as firms fled the stupid rule, eroding the economy. A tad overstated, perhaps—banks need a European hub, and Britain’s competitive advantage is huge—but fair enough. (The court, predictably, is unsympathetic.) Widely discussed, though—the market has probably dealt with it.

There is another high-potential negative, though perhaps years downstream. Bonuses are discretionary compensation—variable costs. Paying big bonuses lets banks keep salaries low, giving them more flexibility to get lean in tough times. But banks aren’t so dumb. They need top talent! If they make everyone take pay cuts, talent will flee to other industries. So they’ll amp up salaries and pay smaller bonuses, keeping total compensation roughly the same. Here’s the problem: Salaries are a fixed cost. The next time trouble hits and revenues dive, bonus-cutting won’t get costs in line. Banks will face a choice: Make massive layoffs or take huge losses and fail. This is a fundamental negative for banks somewhere down the line. Not in the next 30 months! Not for current markets. But someday. It is an elephant that will remain patiently, quietly, unseen in our room awaiting crisis-oriented movement.

What’s Worse Than a Politician?

Many unseen negatives don’t come from Congress. At least not directly. Lawmakers have their faults, but sometimes they realize they’re collectively stupid and not experts in business, so they outsource rule-writing when they reform regulations. They did this with the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. The law itself was about 2,000 pages deferring action to regulatory bodies—the SEC, Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Office of Thrift Supervision and so on. Some provisions were placeholders for actual rules. Others mandated studies, with loose directions for the regulators to write rules later if they decided it was necessary.

There is an elephant here, and it is a bad one! To many, outsourcing rulemaking sounds sensible. Again, members of Congress aren’t bankers. They aren’t experts, so of course they can’t write rules governing banks without inflicting collateral damage. From that viewpoint, having the regulators do the dirty work sounds logical. Even good!

Here’s the problem. Regulators often don’t know their own bounds, and often no one really manages or monitors them. Congress technically has oversight, but this usually amounts to snoozing through the occasional testimony. In practice, regulators can be police, judge and jury.

Regulators also operate in the shadows. When Congress makes a law, everything plays out in public. You can read every draft online, at www.govtrack.us. You can watch the debates on C-SPAN. Journalists observe and report on the debates and negotiating. Negatives are discovered and often pre-priced. You don’t always get this when regulators write laws! They do much of it behind closed doors. You don’t get hundreds of politicians debating a rule publicly in daylight. You get a dozen unelected, unsupervised well-meaners working in secret.

When unchecked regulators write nasty things into laws that can take effect without long public comment, bad things happen fast. The huge recent disaster, covered in Chapter 1, was FAS 157, the mark-to-market accounting rule. We saw a minor example in December 2013, when the feds released the final draft of the Volcker Rule.

The Volcker Rule, part of Dodd-Frank, started as former Fed head Paul Volcker’s three-page proposal to ban banks’ proprietary trading—trading for their own book, not customers’ accounts. Another misdirected effort to prevent a 2008 repeat—proprietary trading didn’t cause the crisis. Banks wrote down assets they planned to hold to maturity, not securities in their trading books. (They already marked those assets to market.) According to the Government Accountability Office, the six biggest banks realized just ![]() 15.8 billion in trading losses from Q4 2007 to Q4 2008.14 Peanuts! A prop-trading ban wouldn’t have saved Lehman Brothers. But politicians will never see this.

15.8 billion in trading losses from Q4 2007 to Q4 2008.14 Peanuts! A prop-trading ban wouldn’t have saved Lehman Brothers. But politicians will never see this.

When Congress passed Dodd-Frank, it outsourced the Volcker Rule to the Fed, FDIC, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and SEC. This alphabet soup released a draft in 2011 for public comment—nice of them—and the public commented. The regulators went back to work, reviewed the comments and rewrote parts of the law. On December 10, 2013, they released the rewrite, called it a final rule and made it effective in July 2015. No ifs, ands or buts (they said).

Problem was, the final rule contained some nasty nuggets that weren’t in the draft. One banned banks from holding collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) backed by trust-preferred securities—TruPS-backed CDOs, in bankerspeak. I’ll spare you the boring technical details here, but these were pooled debt securities community banks have long owned without trouble. They (used to) have favorable accounting and regulatory treatment, and they pay nice interest, so banks would buy and hold them to maturity. Under the amended Volcker Rule, however, collecting income meant banks had an ownership interest (rather than passive stakes). No-no time! This forced banks to reclassify TruPS-backed CDOs as “available-for-sale” assets and mark them to market. Uh-oh!

Within two weeks, Zions Bancorporation—a Utah-based regional bank—announced a ![]() 387 million write-down on TruPS-backed CDOs, blaming Volcker. The American Bankers Association (ABA) sued the feds, claiming community banks were whacked without cause. The public hates big banks, not so much small banks, so the feds bent. But they haven’t patched a similar rule banning banks from owning certain collateralized loan obligations, which the ABA estimates could trigger a

387 million write-down on TruPS-backed CDOs, blaming Volcker. The American Bankers Association (ABA) sued the feds, claiming community banks were whacked without cause. The public hates big banks, not so much small banks, so the feds bent. But they haven’t patched a similar rule banning banks from owning certain collateralized loan obligations, which the ABA estimates could trigger a ![]() 70 billion fire sale. Nowhere big enough to cause a 2008-style write-down spiral, but illustrative.

70 billion fire sale. Nowhere big enough to cause a 2008-style write-down spiral, but illustrative.

Not all regulatory wrangling comes from Congressional outsourcing. The Executive branch does damage on its own, too. The Treasury introduced some unseen negatives in 2014 when they cracked down on “inversion” mergers and acquisitions (M&A) deals—where an American company buys a smaller foreign company and moves corporate headquarters there for tax purposes. America has the dubious distinction of being the only major developed country to tax companies’ foreign earnings after they’ve already paid foreign taxes. Companies pay only if they repatriate earnings, so piling up cash abroad is an obvious solution, but firms want to invest here! Inversions are the solution. By becoming “foreign,” companies could bring foreign earnings back to America and invest as they see fit, while reducing tax costs. A win-win. But you won’t read that in media.

Inversions became a bogeyman. Politicians hate losing tax dollars! So they spun a shaggy dog story about inversions whacking business investment (ignoring that inversions’ primary purpose is to enable investment!). It caught on fast. The Treasury tried to goad Congress into legislating a ban, calling it their patriotic duty, but gridlock got in the way. So the Treasury took action, “reinterpreting” the tax code to make inversions more difficult and to chip at the benefits—they banned some creative transactions that inverted firms would use to transfer earnings back to America. The logic here is inverted (pun intended)—if you say you hate inversions because they kill investment, the solution shouldn’t make investment more difficult.

But that isn’t the elephant in the room here—most firms don’t care about inversions. They care about rules changing. Usually Congress changes the rules, but the Treasury set a precedent by rewriting rules when Congress couldn’t! The changes were small and toothless, but they chipped at the law, changing the game. Now firms have to wonder: “If the Treasury can do this, what else can they do? What other rules will they tweak? How the heck do I plan for it? How can I, when I don’t know how in the h-e-double-hockey-sticks they’ll try to hurt me?”

This uncertainty discourages risk taking. Why make a bold move or start a long-term project with high up-front costs if regulators could change the rules with no warning and pinch your profits? Forget it!

These are small negatives, but illustrative of the unseen surprises the budding contrarian wants to watch for. Train your brain to look for these, and you’ll have an easier time spotting the big one—the unseen rule change that could wipe a few trillion off world GDP and kill a bull market.

Why the Government Already Made the Next Crisis Worse

I have one more story for you before we kiss politics good-bye and move to more polite topics. There is one more source of unseen political risk. Risk doesn’t come just from laws and rules! Politicians’ non-rulemaking actions have consequences, too. Actions send messages—sometimes terrible ones that turn into ticking time bombs. The Obama administration created a big time bomb in the wake of the 2008 crisis—one every savvy investor should know and learn from.

Politicians have one purpose in life: getting elected. Most don’t think past “Will this get me votes?” when making decisions. If their voting public thinks a business or industry is a villain, politicians are all too happy to crucify it.

After 2008’s panic, people decided banks were villains. Evil rent-seekers that forced loans on naïve folks who didn’t qualify, knowingly packaged bad loans into toxic securities, defrauded Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into buying them, gleefully foreclosed on innocent people when housing crashed, and made off with hundreds of billions in taxpayer money. The public demanded their pound of flesh, and pandering politicians delivered five. They didn’t care that the popular narrative was ridiculously false—only votes mattered! From 2010 through August 2014, the government slapped over ![]() 125 billion in crisis-related legal fines on the six largest banks. Probably more by the time you read this. Not important by itself (except to them).

125 billion in crisis-related legal fines on the six largest banks. Probably more by the time you read this. Not important by itself (except to them).

JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America account for over ![]() 100 billion or 80% of the total. Trouble is, most of the lawsuits and charges weren’t really against them. They were against the firms JPMorgan and Bank of America bought during the crisis. Those acquisitions did Washington a favor. If this is how the government “thanks” banks who help by buying failing banks in a crisis, it sends a message: Don’t help us again. Pretty amazingly dumb phenomenon.

100 billion or 80% of the total. Trouble is, most of the lawsuits and charges weren’t really against them. They were against the firms JPMorgan and Bank of America bought during the crisis. Those acquisitions did Washington a favor. If this is how the government “thanks” banks who help by buying failing banks in a crisis, it sends a message: Don’t help us again. Pretty amazingly dumb phenomenon.

This cuts against over a century of crisis management tradition. Healthy big banks have long helped during financial crises. They lend to or buy failing banks and guarantee customers’ deposits, helping prevent bank runs. When they buy, they assume the liabilities, but they also get the assets (on the cheap) and the customers. This isn’t charity—it makes business sense in the long run. But we’ve done it every crisis (and some in between).

JP Morgan—the man and his bank—rode to the rescue during the Panic of 1893, engineering and guaranteeing the government bonds sold to repatriate gold from foreign investors and replenish reserves. He effectively spent his own money to bail out the US Treasury. He did it again in the Panic of 1907, serving as lender of last resort (that was pre–Federal Reserve). If he determined cash-crunched banks were fundamentally solvent, with solid assets and workable business models, he arranged funding. He cobbled a coalition of strong banks that pooled money to keep struggling ones alive. When brokerage firm Moore and Schley became insolvent after it couldn’t repay over ![]() 6 million (a lot then) in loans backed by shares of the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI), Morgan arranged for US Steel (which he controlled) to buy the stock and ultimately buy TCI. Moore and Schley was saved. He also bailed out New York City, helping save the New York Stock Exchange.

6 million (a lot then) in loans backed by shares of the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI), Morgan arranged for US Steel (which he controlled) to buy the stock and ultimately buy TCI. Moore and Schley was saved. He also bailed out New York City, helping save the New York Stock Exchange.

North Carolina National Bank (NCNB) was the savior during our infamous savings and loan crisis (when more banks and money value of banks failed than in the 2007–2009 recession), buying the failed First Republic Bank in 1988. NCNB bought several other failing lenders in Texas and nationally over the next several years. Never heard of NCNB? Or forgot the name? That’s because through a series of mergers it became NationsBank, which bought Bank of America in 1998 and took on the name. For all intents and purposes, today’s Bank of America is the same institution that helped the FDIC time and again in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Ken Lewis, Bank of America’s CEO in 2008, came from NCNB. He was NCNB CEO Hugh McColl Jr.’s right-hand man in 1988, running NCNB Texas National Bank—the entity resulting from the First Republic business. He learned the art of buying failing banks firsthand, and he put it to use in 2008, buying the failing mortgage lender Countrywide and flailing Merrill Lynch. Meanwhile, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon (who was mentored by Citi’s earlier takeover maestro, Sandy Weill) went back to his firm’s roots, buying the ashes of Bear Stearns at the Fed’s behest in March 2008. When Washington Mutual (WaMu) failed in September, JPMorgan Chase bought it as a favor to the FDIC.

Imagine, for a moment, life without these purchases (or Wells Fargo’s purchase of Wachovia). Chaos! Markets started panicking when Bear Stearns appeared to go under—they stabilized and rallied when JPMorgan stepped in. The WaMu purchase saved the FDIC from paying on insured deposits—a huge expense, considering WaMu had an estimated ![]() 165 billion in deposits when it failed.15 Bank of America’s purchase of Merrill Lynch granted the brokerage house access to the Fed’s emergency discount window, keeping it alive and likely sparing huge taxpayer expense. People think the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) was too expensive, but the

165 billion in deposits when it failed.15 Bank of America’s purchase of Merrill Lynch granted the brokerage house access to the Fed’s emergency discount window, keeping it alive and likely sparing huge taxpayer expense. People think the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) was too expensive, but the ![]() 423 billion spent through TARP is nothing compared to the cost if the Treasury and FDIC didn’t have private sector help.16

423 billion spent through TARP is nothing compared to the cost if the Treasury and FDIC didn’t have private sector help.16

This is how the system is supposed to work. You want the private sector to handle this stuff. The private sector does it way better than the government ever could. We saw how that worked when the Federal Reserve and Treasury killed Lehman Brothers after finagling the JPMorgan/Bear merger and effectively nationalizing Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and American International Group (AIG). They arbitrarily picked winners and losers and created sheer panic. If they had to pick the fate of WaMu and Merrill Lynch too? Lord help us.

JPMorgan and Bank of America kept things running, kept customers relatively secure and probably prevented a much deeper panic. The government should have thrown a parade. Instead it turned on the white knights. The feds sued Bank of America for Countrywide’s alleged mortgage fraud. They charged and fined JPMorgan for Bear’s and WaMu’s dirty deeds. All for political gain!

There is a terrible irony here. The banks that threw up their hands in 2008 and said, “Heck no, we won’t help!” didn’t get hurt much. Goldman Sachs paid just ![]() 900 million in fines. Morgan Stanley paid

900 million in fines. Morgan Stanley paid ![]() 1.9 billion. Those that didn’t step in and help didn’t get hurt much. But the good guys got whacked.

1.9 billion. Those that didn’t step in and help didn’t get hurt much. But the good guys got whacked.

By hurting the helpers, the government sent a super-strong message: “Don’t help us bail anyone out ever again.” The good guys heard it. I’ll let Jamie Dimon speak for himself: “Let’s get this one exactly right. We were asked to do it. We did it at great risk to ourselves. … Would I have done Bear Stearns again knowing what I know today? It’s real close.”17 You can believe Bank of America feels the same. Wells Fargo—lucky to escape with just ![]() 9 billion in fines—is watching.

9 billion in fines—is watching.

The next time a big bank goes under, the government could find itself isolated. We’ll all pay a price for politicians’ greed and popularity quest. This is more likely to exacerbate a bear market than cause one. Banks fail primarily in bad times, not good ones! But it is an entirely unnecessary political risk.

Politicians might not be the most dangerous people in America—most aren’t deranged axe murders. But they’re among investors’ worst enemies. The more you know your enemy, the easier it is to beat him.

I’ve told you these stories and chronicled these risks not to scare you—just to help you know your enemy. Now you know his tricks and weapons, and you’re ready for the fight!

Which means we’re also ready for far more pleasant topics! What fun is in store? Time to turn to Chapter 7 and find out!