Chapter 9

Investing in Assessments of Deeper Learning: The Costs and Benefits of Tests That Help Students Learn

The changing nature of work and society in today’s world places a premium not simply on students acquiring information, but on their ability to analyze, evaluate, design, and create new solutions and products. By the turn of the twenty-first century, for example, the top skills demanded by Fortune 500 companies had shifted from reading, writing, and arithmetic to teamwork, problem solving, and interpersonal skills (Cassel & Kolstad, 1998; Creativity in Action, 1990). Employers’ demands for routine skills had waned and had been replaced by a sharp increase in demand for complex thinking and communication abilities (Murnane & Levy, 1996).

Responding to these societal needs, policymakers in nearly every state have adopted the new Common Core State Standards (CCSS) intended to ensure that all students graduate from high school ready for college and careers, with skills for the new economy. These include students’ abilities to analyze, synthesize, and apply what they have learned to address new problems, design solutions, collaborate effectively, and communicate persuasively.

The changes in curriculum and assessment associated with these new expectations will be pronounced in the United States, where current tests tend to measure primarily low-level knowledge and skills. (See chapters 1 to 3, this volume.) The multiple-choice tests common in the United States stand in contrast to the performance assessments used in many other nations, where students are called on to design and conduct investigations, analyze data, draw valid conclusions, report findings, and defend their ideas (see chapter 4, this volume). These countries test students much less frequently with higher-quality assessments: external testing occurs at most once or twice before high school, and some, like Finland, do not have any external tests before the twelfth grade other than those that sample a small subset of students at a couple of grade levels to provide general information.

But performance assessments like those used in other countries were more common in many states during the 1990s, and researchers found they supported stronger instruction and greater student achievement on measures of higher-order skills. This was especially true when teachers were involved in scoring the assessments and reflecting together about how to improve curriculum and teaching. (See chapters 2, 3, and 7, this volume.) Unfortunately, most of these assessments were discontinued because of the countervailing requirements of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), which increased costs because of annual testing requirements and constrained the forms of assessment that could be used.

Solving the cost problem is critical to developing better assessments, which are critical to supporting more ambitious learning goals. The experience of the NCLB era demonstrates that what and how tests measure matters, because when they are used for decision making, they determine much of what happens in the classroom. US policies have increasingly used tests to determine what curriculum students can enroll in and whether they are promoted or graduated; whether teachers are tenured, continued, or fired; and whether schools are rewarded or sanctioned, even reconstituted or closed. As a result, the incentives for teachers to teach to the test have become increasingly intense (Amrein & Berliner, 2002).

Many analysts have found that intensive teaching to narrow tests has reduced time for topics and important subjects that are untested; focused instruction in tested areas on the multiple-choice and short-answer formats of the test rather than supporting more intellectually rigorous analyses; and reduced the emphasis on writing, oral communications, extended problem solving, research, and investigation, all abilities that are critical for college and career readiness (for a summary, see Darling-Hammond & Rustique-Forrester, 2005).

A recent report from the National Research Council noted, “The extent to which [deeper learning] goals are realized in educational settings will be strongly influenced by their inclusion in district, state, and national assessments” because of the strong influence of assessment on instruction in the United States (Pellegrino & Hilton, 2012).

The nation’s tangible expenditures on testing, as well as the costs to instruction, have not been considered in discussions of what kinds of assessment might be desirable as learning goals change. Building on the cost-benefit framework presented by Picus and colleagues in chapter 8, this chapter presents recent data and analysis that illustrate how higher-quality assessments can become affordable.

THE CHALLENGES FOR NEW ASSESSMENTS

The United States is poised to take a major step in the direction of curriculum and assessments for this kind of deeper learning with the adoption of the Common Core State Standards in more than forty states. The accompanying assessments developed by the two state consortia, the Partnership for Assessing Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) and the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC), to be launched in 2014–2015, are slated to include some performance-based assessment tasks. Understanding the importance of assessments to support the teaching of these higher-level skills, a number of states and districts are planning to augment the consortia assessments with more extended assessments like those used before NCLB. Initiatives such as the Innovation Lab Network (ILN) of states and districts, coordinated by the Council for Chief State School Officers, are developing strategies to create more intellectually ambitious assessments that are more internationally comparable. (See chapter 10, this volume.) These performance assessments may be used as formative tools to guide classroom instruction, as components of state assessment systems, in proficiency assessments that replace seat time expectations, as elements of end-of-course examinations, and in graduation portfolios.

The challenge ahead will be for states and districts to prepare to implement new assessments, given the many changes they will entail. On the one hand, there is substantial consensus that US assessments must evolve to meet the new expectations for student learning. On the other hand, there are countervailing pressures regarding funding, time, and traditions that could stand in the way of assessment changes.

Especially given the recent cutbacks in education funding in many states, there is concern that new assessment designs need to be as cost-effective and efficient as possible. At the same time, it is important for these assessments to encourage productive approaches to teaching and learning. High-quality assessments have tended to cost more than lower-quality assessments, primarily because performance tasks and essays require human scoring, whereas low-level skills can be measured with multiple-choice questions that are cheap to score.

EVALUATING INVESTMENTS IN ASSESSMENT

Despite the fact that US education policy relies heavily on tests to guide decisions about students, teachers, and schools, the level of investment in test quality is very low. Many states have budgeted only ten to twenty dollars per pupil for NCLB-required tests in math and reading; as a result, they have had to restrict their tests to multiple-choice methods. With spending on education averaging over ten thousand dollars per pupil, twenty dollars in combined testing costs for math and reading represents less than two-tenths of 1 percent of the costs of K–12 education—less than the cost of half a tank of gas. To get a sense of the relative size of this investment, think about the fact that most of us spend at least three hundred dollars a year for routine check-ups on our automobiles.

Yet this tiny investment in testing has enormous influence on instruction given the accountability policies that attach important consequences to scores. Multiple-choice tests, while inexpensive, produce few incentives to encourage instruction focused on higher-order thinking and performance skills. Open-ended assessments such as essay exams and performance tasks are more expensive to score, but they can support more ambitious teaching and learning.

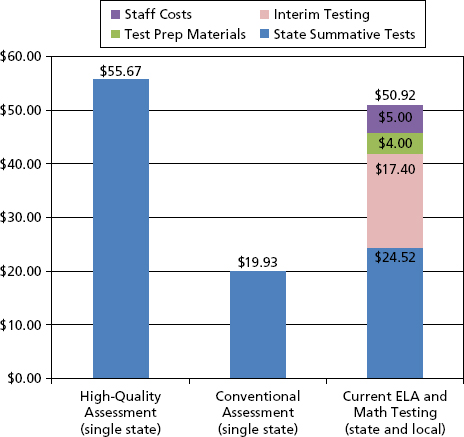

To get an idea of the differences in costs, the Assessment Solutions Group (Topol, Olson, & Roeber, 2010) estimated the current costs of a high-quality assessment conducted by a single medium-sized state. Instead of primarily multiple-choice items, the “high-quality” assessment design would replace about half of the multiple-choice items with short and long constructed-response items, plus both short and long performance tasks. The short tasks are on-demand activities that students complete in a class period involving a written activity or other product. Longer tasks involve students in more extended research or inquiry activities that result in a paper, a completed project, or a presentation. These are scored by trained scorers, who may be teachers.

This high-quality assessment costs about fifty-five dollars per student for English language arts and mathematics combined, as compared to the roughly twenty dollars per pupil that states spend for primarily multiple-choice approaches. (See figure 9.1.) It is easy to see why most states abandoned performance assessments and open-ended items when NCLB more than doubled the amount of required testing by mandating that every child be tested every year in most grade levels. This requirement replaced the earlier Elementary and Secondary Education Act expectation that states report assessment results once in elementary, middle, and high school. The earlier law also allowed the use of sampling rather than testing all students, which states like Maryland took advantage of in order to afford rich performance tasks. (See chapter 5, this volume.)

Figure 9.1 Per Pupil Assessment Costs

Sources: Topol et al. (2010, 2013). Darling-Hammond and Adamson (2013).

Although the federal government contributed to the costs of assessment, Congress chose a level of investment that was pegged to the costs estimated by the US Government Accounting Office (GAO) for the use of multiple-choice tests (US General Accounting Office, 2003). States committed to more extensive performance assessment, such as Connecticut, which included extended writing tasks, science investigations, and other intellectually challenging tasks in its assessments, were unable to afford a large share of the costs of their assessments when NCLB required that every student in certain grade levels be tested annually. Connecticut sued the US Department of Education for the costs of maintaining its rich assessment program under NCLB, and, in the course of negotiations, it was advised by the department to revert to multiple-choice testing (Blumenthal, 2006).

Unfortunately, the apparently economical prices currently attached to state tests do not capture the considerable opportunity costs associated with counterproductive instructional incentives and lack of useful information for instruction. (See chapter 8, this volume.) Missing from the cost calculus are the missed opportunities for assessing and developing higher-order thinking skills, which have consequences for students’ learning and abilities. Nor do these price tags capture many hidden expenditures on interim and benchmark assessments and other test preparation materials and activities that states, districts, and schools spend in current systems. Because of the nature of current summative tests, all of these materials focus on lower-level skills measured in limited ways.

From a cost-benefit perspective, the current approach could be penny wise and pound foolish. Constraining our assessments to instruments that can measure only low-level learning, and then tying decision making that will drive virtually all instructional efforts to what they measure, is a recipe for low-quality schooling. Although they may appear to be low in costs, most states’ current testing systems are not organized to produce the kind of student learning encouraged in high-performing countries.

Ultimately policymakers would like to know whether the benefits of performance assessment (e.g., more valid measurement of student performance and positive impact on classroom practice) justify the burdens (in terms of development costs, classroom time, scoring costs, and so on). The data in chapter 8 suggest that the expenditures and administrative burdens associated with performance assessments, particularly portfolios and extended hands-on science tasks, can be high relative to multiple-choice tests. Yet that is not the end of the story.

First, the benefits may justify the burdens from the perspective of education. For example, Vermont teachers and principals thought their state’s portfolio assessment program was a “worthwhile burden.” In fact, in the first years, many schools expanded their use of portfolios to include other subjects (Koretz, Stecher, Klein, & McCaffrey, 1994), and even in recent years, most Vermont districts have continued the use of the writing and mathematics portfolios, even though they are not used for state accountability purposes. Similarly, Kentucky principals reported that although they found Kentucky Instructional Results Information System to be burdensome, the benefits outweighed the burdens (Koretz, Barron, Mitchell, & Stecher, 1996). Second, as we illustrate in this chapter, the costs associated with performance assessments have declined over the past decade, making it more attractive to incorporate some degree of performance assessment into state testing programs.

WHAT DO WE ACTUALLY SPEND FOR TESTING TODAY?

While cost concerns have narrowed the design of most state tests, districts and schools currently spend quite a bit more to boost achievement on those tests. Two recent independent studies, one from the Assessment Solutions Group and the other from the Brookings Institution, estimated the average combined costs for state English language arts and math tests at $25 to $27 per pupil, with a very wide range: a few states reported spending in the range of $10 to $15 per pupil, and some reported spending more than $50 per pupil (Chingos, 2012; Topol, Olson, Roeber, & Hennon, 2013). The Brookings study found that the lowest-spending states were Oregon, Georgia, and California. On the upper end, Massachusetts, which uses more open-ended items, spent $64 per pupil, and tiny Hawaii spent just over $100 per pupil (Chingos, 2012).

The Brookings study estimated that tests required under NCLB tests cost $723 million annually, paid to vendors that administer the tests.1 With the addition of other subject areas and in-house state spending, these costs more than doubled, to an estimated $1.7 billion annually. Though a large number, this represents only one-fourth of 1 percent of annual national K–12 education spending.

Beyond these costs, however, are the considerable investments some states and nearly all local districts are making in interim and benchmark assessments, test preparation materials and programs, and interventions to improve scores. Two recent surveys of districts, one by the Assessment Solutions Group (ASG); (Topol et al., 2013) and another by the American Institutes of Research (Heppen et al., 2012) found that all the districts they surveyed used interim or benchmark tests, usually developed by or with a vendor.

These tests carry noticeable costs. For example, one widely used online interim test cost $12.50 per student per year (Illinois Department of Education, 2011). Districts also pay for data management systems and, often, test preparation materials designed to improve scores. Test preparation programs range in cost from about $2.00 to $8.00 per pupil.2

Based on data from 189 districts and one state that sponsors statewide interim tests, ASG found that interim testing costs ranged from about $6 to $60 per pupil in 2011, with an average of $17 to $18 per pupil. By ASG estimates, the average costs of state tests and local benchmark assessments in English language arts and mathematics are about $42 per pupil. These estimates do not include test preparation materials or staff time for development, administration, analysis of the data, or professional development related to the assessments. Topol and colleagues (2013) note:

All in all, most states and their districts are spending $35–$55 per student on testing [for English language arts and mathematics], not counting any of the related human resource and other time that goes into the testing and test preparation, professional development, data analysis, interventions and supplemental education services designed to raise scores, all of which are pointed at relatively narrow kinds of learning that have a dubious relationship to the skills and abilities students are now being called upon to acquire. In total, these investments amount to many billions of dollars of educational investment that may not be leveraging the kinds of instruction the Common Core standards and understandings of 21st century skills require. (p. 12)

Appendix D illustrates these costs for three states, selected to represent the range of current spending on tests. California is currently one of the lowest-spending states, Kentucky is a mid-spending state, and Massachusetts is one of the highest-spending states. In brief, as table 9.1 shows, combined state and local spending in these three states on NCLB-required ELA and mathematics testing ranges from $30 to $87, with Kentucky near the national average, at $40. The state-provided data for Kentucky do not include the additional costs of interim testing (e.g., data systems, materials, teacher scoring) reported in the surveys for the other two states. Based on the reports of districts that could calculate these costs, a conservative estimate would be an additional 20 percent on top of the interim testing costs that are paid to test vendors. This would bring Kentucky’s total for ELA and math testing at the state and local level to approximately $43 per pupil, very close to the ASG national estimate of $4 per pupil.

Table 9.1 Estimated Costs for State Tests Plus Local Interim Testing

| California | Kentucky | Massachusetts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interim testing costs | $14.71 | $15.04a | $23.39 | |||

| All tests | ELA plus math | All tests | ELA plus math | All tests | ELA plus math | |

| State testing costs | $19.64 | $16.63 | $51.68 | $24.95 | NA | $63.75 |

| State + local costs | $34.35 | $31.45 | $66.72 | $39.99 | NA | $87.39 |

| aKentucky’s estimate for interim testing costs, provided from a state data set, does not include costs beyond those allocated directly for vendor test fees (e.g., data management systems, teacher scoring). | ||||||

None of these estimates include what states and localities spend for test preparation materials (about $4 per pupil on average) and the staff costs associated with administering and scoring the tests (at least $5 per pupil). Adding these costs would place the average costs of state and local testing in the areas of English language arts and mathematics at over $50 per pupil. (See table 9.1.)

Because of pressures to teach to the test in high-stakes accountability systems, the additional costs for interim and benchmark testing have become viewed as mandatory. Ironically, these combined costs of test preparation, interim testing, and summative testing are very close to the costs of operating a much higher-quality summative assessment that would involve students in challenging performances. However, in most cases, the current expenditures do not improve the quality of assessment or leverage higher-quality instruction because they are focused on raising scores on current state tests, which measure mostly low-level skills.

This raises an important question: Might our nation’s schools be able to improve test quality and better invest valuable resources with a more integrated, higher-quality assessment system, especially if resources currently spent in uncoordinated, fragmented ways can be coordinated to support complementary assessment activities that focus on higher-order skills?

REALIZING THE BENEFITS OF HIGH-QUALITY ASSESSMENTS

In order to realize the benefits of high-quality assessments, it will be important to figure out how to make them both affordable and feasible to implement in state and local school systems. Doing this will depend on:

- Having a vision of a high-quality assessment system and how it can operate to strengthen learning

- Taking advantage of cost savings associated with consortia and productive uses of technology

- Involving teachers in scoring assessments in ways that also support teacher learning and improved instruction

- Being strategic about combining state and local resources to make sound, coherent investments in high-quality assessments

Developing a Vision of a High-Quality Assessment System

Over a number of years, the Council for Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) has worked with key stakeholders to develop a set of principles for student assessment systems. These principles suggest that the student assessment process should be considered a system that supports a variety of purposes, such as informing learning and instruction, determining progress, measuring achievement, and providing information for accountability. A CCSSO report outlined key elements of high-quality assessment systems:

- Standards guide an integrated system of curriculum, assessment, instruction, and teacher development. Formative tools, along with interim and summative assessments, are connected to a common curricular vision tied to professional learning. Thus, everything that informs the work of schools is well aligned and pulling in the same direction.

- State and local assessments work together to provide a balance of assessments offering evidence of student performance on challenging tasks that evaluate applications of knowledge and skills. State and local assessments work together to evaluate a broad array of competencies that generalize to higher education and careers. Components of the assessment system should evaluate students’ abilities to find, analyze, and use resources; communicate in multiple forms; use technology; collaborate with others; and frame and solve complex problems.

- Teachers are integrally involved in the development of curriculum and the development and scoring of assessment measures. The assessment systems are designed to increase the capacity of teachers to prepare students for the demands of college and careers by involving them in moderated scoring of the assessments, which enables them to deeply understand the standards and develop stronger curriculum and instruction.

- Assessment measures are designed to improve teaching and learning. Successful systems emphasize the quality of assessments over the quantity. They invest in a set of formative and summative approaches that support the learning of ambitious intellectual skills in the classroom. Assessment as, of, and for learning is made possible by (1) the use of curriculum-embedded assessments, which provide models of good curriculum and assessment practice, contribute to curriculum equity across classrooms, and allow teachers to evaluate student learning in support of teaching decisions; (2) close examination and scoring of student work as sources of ongoing professional development; and (3) use of learning progressions that allow teachers to see where students are on multiple dimensions of learning and to strategically support their progress.

- Accountability systems are designed to evaluate and encourage multiple dimensions of student success. Both student assessments and school accountability are based on multiple measures. Beyond test data, school indicators may include student participation in challenging curricula, progress through school, graduation rates, college attendance, citizenship, a safe and caring climate, and school improvement. When evaluating schools, many nations include information from school inspections in which experts closely examine teaching, learning, and school operations in order to diagnose school needs and guide targeted improvement efforts (Darling-Hammond, 2010).

Making High-Quality Assessments Affordable

Recent advances in a number of areas have made renewed efforts to implement performance-based assessments more financially viable. Cost savings are associated with advances in computer-based scoring of open-ended items and tasks plus more economical approaches to teacher scoring, as well as the savings of computer-administered assessments, and the economies of scale that states realize as part of a consortium.

In a recent study, ASG found that the cost of higher-quality assessments—that is, tests that replace half of the usual multiple-choice items with open-ended items and performance tasks—can be significantly reduced in these ways (Topol et al., 2010):

- Participating in a state assessment consortium

- Using online delivery of assessments

- Scoring open-ended items and tasks through computer-based scoring or by using teachers who are paid professional development stipends

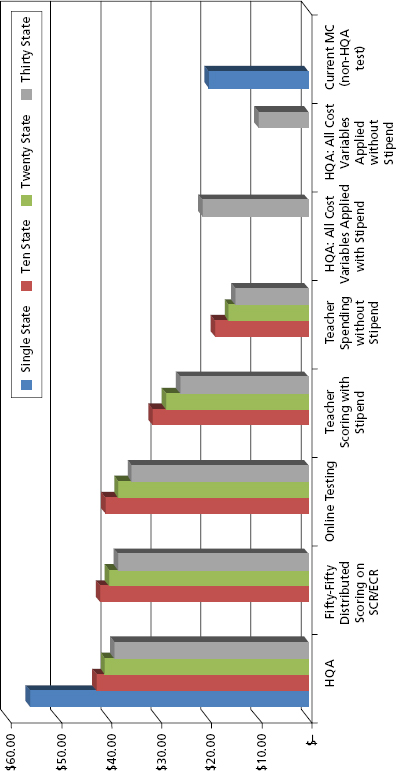

Based on data ASG collected in 2010, the fifty-five dollars estimated as the cost for a state to administer high-quality assessments would be reduced by just over half if all of the cost-savings approaches were applied (Topol et al., 2010). Thus, increasing assessment quality appears to be an achievable goal. Figure 9.2 shows the total cost per student for the different models that were analyzed. As can be seen, total costs are almost three times higher for the high-quality assessments than for the traditional assessment (nearly fifty-six dollars compared to twenty dollars). This is primarily due to the increased costs for scoring of constructed response and performance items in the high-quality assessments. However, if these items are scored by teachers instead of by the vendor, the total costs can be reduced by about 25 percent if teachers earning stipends are used and by about half if teacher time is part of otherwise-covered professional development time.

Figure 9.2 Expenditures per Student for a High-Quality Assessment (HQA)

Participating in an assessment consortium reduces the total costs significantly. Larger consortia are able to achieve more savings than a ten-state consortium, but the savings secured as states increase are not linear. Various online assessment delivery strategies were analyzed and found to have some additional benefit in reducing the cost of the HQA. Combining all cost-reduction strategies in a thirty-state consortium that pays teachers a $125 per day stipend to score peformance tasks results in a cost per student of only $21—about what is spent by a typical state for its current, largely multiple-choice, assessment.

In these estimates, the greatest savings are realized by being part of a multistate consortium that can share fixed costs by using teachers for scoring and by delivering assessments online rather than in paper-and-pencil format (as both of the two new assessment consortia plan to do).

Computer-based scoring of some items can also realize savings. Such software has been studied extensively in recent years and has been found, for some kinds of items, to produce relatively comparable results to hand scoring by humans. (See chapter 5, this volume.) Currently, scoring based on computerized artificial intelligence (AI scoring) is more effective with extended constructed-response items or essays where linguistic features are a major aspect of the scoring than with shorter open-ended items, items that must evaluate the relationships between concepts being discussed, or items that must evaluate the correctness of specific, complex information, including those that include multiple representations of ideas (e.g., mathematical modeling tasks that include graphic, written, and formula responses). The cost can be considerable for developing the algorithm for scoring each item, which often relies on extensive human scoring followed by analysis of scoring elements and “tuning” of the scoring engine. Where it can be used successfully, computer-based scoring that uses artificial intelligence engines is less expensive than human scoring by trained teachers. However, both of these methods are less expensive than vendor scoring (Topol et al., 2010).

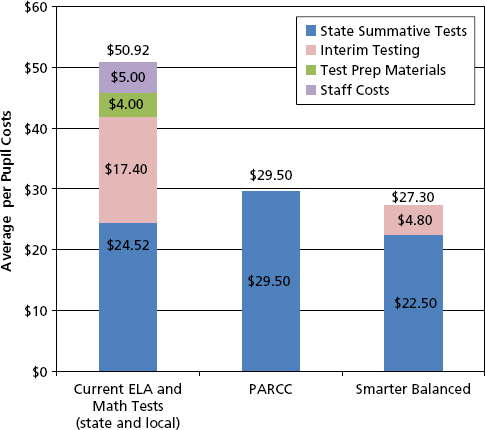

Indeed, promises of savings that permit higher-quality assessments for a much lower price than states could experience individually appear likely to be realized. Recently the Smarter Balanced and PARCC consortia announced expected costs to states for systems that include formative and interim tools and more performance-based items that are far lower than most states are paying now for lower-quality tests (figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3 Average per Pupil Costs for State and Local Tests in ELA and Math, 2012

AI scoring may become more cost-efficient over time while still allowing for items that are sufficiently complex to measure the standards. Getting to that point will require additional research tied to extensive experience in human scoring of complex tasks, because it is analysis of this scoring experience that provides the means for training an AI engine. In the meanwhile and even after, there are many benefits to including teachers in the scoring of performance-based assessments.

Making High-Quality Assessment Feasible

If we believe that assessment systems should encourage the kinds of learning students will need for later success, it will be important to figure out how to develop and use what Lauren Resnick (1987) has termed “tests worth teaching to.” To realize the benefits of high-quality assessments and to make them feasible in the United States, at least two things will be needed.

First, strategies must be devised for involving teachers in scoring to increase the benefits and reduce the costs of high-quality systems. High-achieving systems in many countries increase the benefits of performance assessments and offset the costs by engaging teachers in developing, reviewing, scoring, and using the results of assessments. Comparability in scoring is achieved through the use of standardized rubrics, as well as training, moderation, and audit systems that support consistency in scoring. The moderation process in which teachers learn to calibrate their scoring to a standard is a strong professional learning experience that enables teachers to deeply understand the standards and the kind of student performance they require. This sparks conversations about revisions to curriculum and teaching. As teachers become more skilled at using new assessment practices and developing curriculum, they become more effective at teaching the standards. Thus, the assessment systems increase the capacity of teachers to prepare students for the demands of college and careers in this new century and global society.

These teacher scoring strategies are like those that are currently used in the Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate programs in the United States, as well as those used in states that launched leading-edge assessment systems during the 1990s, such as Connecticut, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, New York, and Vermont. Research about the outcomes of these systems has found that they support growth in teaching and gains in student outcomes on assessments of higher-order skills (see chapter 7, this volume).

Like European and Asian countries, New York State has long maintained its Regents Examination program, which includes open-ended essays and tasks, by setting aside days for teacher scoring. Other states have also engaged teachers in scoring as part of professional development time, knowing that teachers learn about their students and their instruction during the scoring and debriefing process.

Table 9.2 shows assessment costs under three scoring assumptions: traditional scoring by a test vendor, scoring by trained teachers paid $125 a day, and costs if teachers engage in scoring as part of already-planned professional development. The table shows that the cost of the assessment program is substantially lower when states’ teachers are used for scoring and if the cost of this scoring is associated with the professional development budget. These costs decline somewhat in consortia with more states. Using teachers to score performance items as part of their compensation or professional development makes a substantial difference, reducing costs to $18.70 per student in the ten-state consortium and $14.57 in the thirty-state consortium. Paying teachers a stipend of $125 a day still saves significant costs and results in an assessment cost of $31.17 per student at the ten-state consortium size and $25.71 at the thirty-state consortium size. With very large consortia, the $25.71 per student cost of the assessment is at the mid-range of today’s high stakes assessments.

Table 9.2 Assessment Costs under Different Teacher Scoring Assumptions

| Consortium Size | Contractor Cost (On-Site Scoring) | Teacher Stipend ($125) | Teacher Professional Development Scoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ten states | $42.41 | $31.17 | $18.70 |

| Thirty states | $38.83 | $25.71 | $14.57 |

States could make scoring of open-ended assessments more affordable by making creative use of existing professional development days and using existing incentives, such as continuing education requirements that would offer units for engagement in scoring and associated discussions of curriculum and instruction. This would link professional development and assessment budgets in a cohesive project that helps teachers improve instruction, assessment, and delivery of standards.

As noted earlier, technology can be used to make new assessments more efficient and affordable by delivering the assessments; in some cases, scoring the results; and by delivering responses to teachers who are trained scorers so they can evaluate them from an electronic platform. Such a platform can also support calibration of scorers and moderation of scores. These technologies are already being used in the International Baccalaureate and Hong Kong assessment systems, both of which include open-ended tests along with classroom-based papers and projects in their examination systems.

In order to gain the cost benefits of machine scoring and the teaching and learning benefits of teacher-moderated scoring, a mixed system could be developed. Computer-based scoring can be used for constructed-response tasks where appropriate, while teachers score a proportion of these tasks for anchoring and learning purposes. Meanwhile, teachers can be engaged to score tasks that require more nuanced professional judgments, which will also support instruction focused on more challenging forms of learning.

Second, realizing the benefits of high-quality assessments and making them feasible in the United States also requires strategies for pooling resources to enable more integrated systems of formative and summative assessment that better represent higher-order skills.

Although considerable state and local resources are currently spent on testing, these investments generally do not leverage higher-quality teaching or assessment because they are focused almost exclusively on boosting scores on tests of lower-level skills. Furthermore, investments from states, districts, and schools are fragmented and uncoordinated, so they do not support alignment of effort or economies of scale.

The goal for states should be to create the kind of teaching and learning system that many other countries have built to provide an integrated approach to curriculum, instruction, assessment, and teacher development. The new assessment consortia, PARCC and Smarter Balanced, could offer a first step in this direction as they seek to build coherent systems of formative supports, along with interim and summative assessments that include greater focus on higher-order skills.

To take advantage of these possibilities and enhance the quality of learning, states will need to think about their investments in standards as more than the line item for testing in the state budget. They will need to connect interagency planning and pool resources for curriculum, assessment, and professional development so that these elements are mutually reinforcing.

CONCLUSION

Testing in the United States has been shaped by pressures to test frequently and inexpensively, and studies have found that most state tests focus almost exclusively on multiple-choice questions that measure low-level skills. Educators and policymakers know that assessments need to evolve to support college and career readiness. In order to meet the demands of a knowledge-based economy and the expectations represented in new Common Core State Standards, assessments must better represent more complex competencies.

Currently the average state testing system in English language arts and mathematics costs $25 to $27 per pupil. However, the pressures of meeting accountability requirements have caused states and localities to add additional interim and benchmark tests, as well as spending for data systems and test preparation. In combination, these expenditures now average closer to $50 per pupil.

These resources, which still total less than 1 percent of overall per pupil spending, could support much higher-quality assessments, including performance tasks that include critical thinking and problem-solving skills, if they were refocused to do so. To shift our current systems of assessment, states and districts will need to support higher-quality assessments through a combination of strategies:

- Cost savings, such as the economies of scale enabled by state consortia, online delivery, and efficient scoring of open-ended tasks by teachers and computers

- Strategic reallocation of resources currently used for state and local testing in fragmented ways that are not focused on improved assessment quality

- Use of professional learning time and incentives to support teacher engagement in assessment scoring, development, and use, which provide the double benefit of improved instruction and more efficient use of resources

The question for policymakers has shifted from, “Can we afford high-quality assessments of deeper learning?” to, “Can we afford not to have high-quality assessments?” The answer is that assessments of deeper learning are needed to provide the impetus for students to develop skills for the knowledge economy, a prerequisite for global competitiveness and for the long-term well-being of the nation.