Chapter 10

Building Systems of Assessment for Deeper Learning

Reform of educational standards and assessments has been a constant theme in nations around the world. As part of an effort to keep up with countries that appear to be lengthening their educational lead over the United States, the nation’s governors and chief state school officers have issued the Common Core State Standards to specify the literacy and numeracy skills needed for success in the modern world. This goal has profound implications for teaching and testing. Genuine readiness for college and careers, as well as participation in today’s democratic society, requires, as President Obama has noted, much more than “bubbling in” answers on a test. Students need to be able to find, evaluate, synthesize, and use knowledge in new contexts, frame, and be able to solve nonroutine problems and produce research findings and solutions. The rapidly evolving workplace increasingly requires students to demonstrate well-developed thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, design strategies, and communication capabilities.

In addition, college faculty have identified critical thinking and problem solving as areas in which first-year college students are lacking when they enroll (Conley, 2005, 2014). As important as these skills are, the educational policy system and the larger political system are not functioning effectively to foster their development and implementation in US schools. A decade of test-based accountability targeted narrowly on reading and mathematics did help to focus schools on the importance of these subjects. However, in the process, the natural and necessary progression from basic skill acquisition to more complex application of these skills was disrupted. Unfortunately, there are few incentives in today’s policy system for educators to help students develop these skills. New systems of curriculum, assessment, and accountability will be needed to ensure that students are given the opportunities to learn what they need to be truly ready to succeed in college and careers.

ASSESSING WHERE WE’VE BEEN AND WHERE WE ARE GOING

Previous chapters have reviewed the narrowing of instruction that has occurred as a result of the high stakes associated with widely used multiple-choice tests. The focus on test preparation has been accompanied by less emphasis on skills such as written and oral communication, complex problem solving, and investigation that involves evaluation of evidence or application of knowledge (Darling-Hammond & Rustique-Forrester, 2005).

However, the recent advent of the Common Core State Standards provides an impetus for state legislators, governors, and educational leaders to rethink what it is that they want from public schools. This era of open thinking about how schools should be judged creates new opportunities to consider what it is that students should be expected to know and be able to do and how these things can best be measured.

The opportunities may be increased by the US Department of Education’s efforts to offer flexibility with respect to critical aspects of No Child Left Behind (NCLB). This flexibility opens the door to assessment systems that accommodate more ambitious learning goals and new accountability structures. Forty-four states have requested flexibility, and as of January 2014, forty-two state requests had been approved. An analysis of these waivers and flexibility requests indicates shifting state priorities, including an emphasis on developing college and career readiness as a key focal point for state education systems.

Concomitant with the implementation of the Common Core State Standards is the development of assessments designed to measure them. The two consortia of states that are designing the new assessment systems have taken on the challenging task of trying to measure all of the Common Core standards—113 in English/language arts/literacy and 200 in mathematics—with one set of tests. This task is particularly challenging given the range of cognitive complexity in the standards and the degree to which many standards can be defined only in relation to performance standards that specify the necessary challenge level for the course work that is ultimately used to teach them.

The Common Core State Standards are designed to specify much of the reading, writing, language, and mathematics knowledge and skills students need to be college and career ready. However, they do not claim to address everything that is necessary for postsecondary success, such as the interpersonal skills, perseverance, resilience, and academic mind-set that have been found to be as important as academic skills. In addition, the consortia assessments are not able to assess a number of important standards from among the Common Core standards, including oral communications, collaboration, and the capacity for extended investigations and problem solving. Finally, they will not test the application of English and mathematics skills to other subject areas or specify standards for the rest of the core academic curriculum. Therefore, more means of assessment will be needed to gauge the full range of knowledge and skills that comprise readiness for college and careers.

DEFINING COLLEGE AND CAREER READINESS

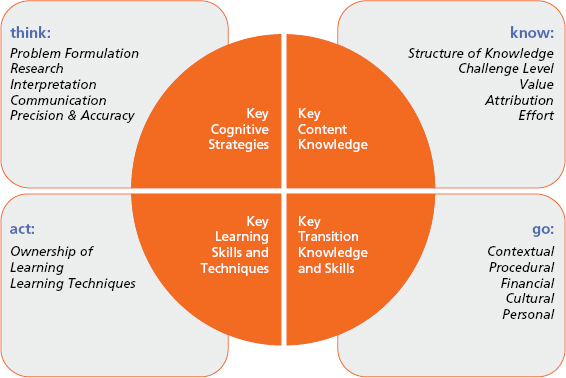

College and career readiness is a complex construct. The model developed by Conley (2014) contains seventeen aspects and forty-one components organized into four “keys”: Key Cognitive Strategies, Key Content Knowledge, Key Learning Skills and Techniques, and Key Transition Knowledge and Skills (figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1 Four Keys to College and Career Readiness

No one test, however innovative it is in terms of item types, can hope to address all or even most of these variables. More important, many of these need to be measured in low-stakes contexts, with feedback provided to students on where they stand relative to the goal of being college and career ready, not with the intent of classifying them or withholding a benefit, such as access to a particular program, curriculum, or diploma. For example, here are a number of important Common Core standards that, due to their very nature, the consortia assessments will not measure directly:

- Conducting extended research using multiple forms of evidence

- Communicating ideas—discussing or presenting orally or in multimedia formats

- Collaborating with others to define or solve a problem

- Planning, evaluating, and refining solution strategies

- Using mathematical tools and models in science, technology, and engineering contexts

It is easy to see from these examples that many of these standards are very important to being a well-prepared student who plans to pursue a bachelor’s degree or a career certificate. It is also readily apparent that these standards require a wider range of assessment techniques, many of which will work best in a classroom environment. For example, assessing student ability to conduct research and synthesize information would best be done through a research paper. The standard for planning, evaluating, and refining solution strategies suggests a multistep process where evidence is generated at multiple points in the process. Designing and using mathematical models is a task that occurs most naturally in other subject areas, such as the natural and social sciences and engineering, with complex problems set in real-world contexts.

The rich instructional experiences and products that result from such efforts should be able to inform teaching and student improvement rather than merely produce scores that are determined outside the school and sent back as two-digit numbers that reveal little about what students have actually accomplished. Although these products might inform summative judgments, they should also serve formative purposes: helping teachers understand student thinking and performance and helping students understand how they can continue to revise and improve their work.

The new assessments present many opportunities as well as challenges. The process of developing and implementing new assessments on this scale offers a once-in-a-generation chance to rethink the way student learning is supported and evaluated within each state. A state will be able to consider moving beyond an assessment system composed of often overlapping, redundant, or disconnected tests and toward a system of assessments that is based on using a range of measures that yield comprehensive, valid, and vital data for a variety of purposes. Among these, a critical priority is to enable teachers to improve instruction and students to improve their learning.

DEVELOPING SYSTEMS OF ASSESSMENT

Systems of assessment are designed strategically to offer information for distinctive purposes to different audiences: students, parents, teachers, administrators, and policymakers at the classroom, school, district, and state levels. A system of assessment may include large-scale assessments that offer information to policymakers (these are sometimes conducted on a sampling basis rather than for each student), along with much richer school or classroom assessments that offer more detailed information to guide teachers as they develop curriculum and instruction and students as they revise their work and set learning goals.

Colleges and employers can benefit from both summary data (e.g., grade point averages or test scores) and, in certain circumstances, more complex and authentic examples of students’ work such as essays or other writing samples, work products students have designed or fashioned, and presentations that showcase their thinking.

In its description of its new assessment framework, New Hampshire’s Department of Education (2013) notes:

Comprehensive assessment systems are generally defined as multiple levels of assessment designed to provide information for different users to fulfill different purposes. Most importantly, information gathered from classroom and school assessments should provide information to supplement accountability information generated at the state level, and state level assessments should provide information useful for evaluating local education programs and informing instructional practice. Further, the large-scale assessment should signal the kinds of learning expectations coherent with the intent of the standards and the kinds of learning demonstrations we would like to see in classrooms. (p. 9)

A key point in New Hampshire’s approach is that large-scale assessments should signal important learning goals and be compatible with the kinds of teaching that are desired in classrooms, and they should work in tandem with local assessments to meet information needs.

Current testing regimes in most states typically lack this kind of coherence and synergy and fail to measure deeper learning skills. However, a number of states developed thoughtful systems of assessment during the 1990s, and many countries have robust examples of such systems that have been in operation for long periods of time.

Examples of State Systems

As described in chapters 2 and 3, during the 1990s, a number of states developed standards-based systems of curriculum and assessment that included large-scale, on-demand tests in a number of subject areas—usually once in each grade span (3–5, 6–8, and 9–12), plus classroom-based assessments that involved students in completing performance tasks, such as science investigations; research, writing, or art projects; and portfolios of student work assembled over time to illustrate specific competencies.

These systems were designed to offer different kinds of information to different stakeholders. The on-demand tests usually included a combination of multiple-choice and short constructed-response items, with longer essays to evaluate writing. These scores informed state and local policymakers about how students were doing overall in key areas.

Going beyond these components, Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, New York, and Vermont involved students in classroom performance tasks of longer duration—from one class period to several—designed at the state level and administered and scored locally, with a moderated scoring process to ensure consistency. Maryland was able to mount an ambitious set of tasks across subject areas by using matrix sampling, which meant that different groups of students completed different tasks and the results could be aggregated across an entire district or state to report on more aspects of learning culled from across all the tasks.

Minnesota, Oregon, Wisconsin, and Wyoming introduced more individualized learning profiles of students that allowed students to demonstrate specified competencies through locally developed performance assessments. Minnesota’s Profiles of Learning set out expectations for graduation readiness in ten domains not tested in the state’s basic skills tests. For example, in social studies, the inquiry standard could be met with an issue analysis that required the student to research an issue and evaluate proposed positions or solutions by gathering information on the issue, evaluating points of view, looking for areas of difference and agreement, analyzing feasibility and practicality for proposed solutions, and comparing alternatives and their projected consequences. Oregon’s Certificates of Initial and Advanced Mastery included similar tasks that students could complete to demonstrate their competencies in various areas. These could then be recorded on the diploma. Students could use these competency demonstrations to meet proficiency-based entrance requirements at Oregon’s public universities.

Graduation portfolios in Rhode Island and New York have taken this idea a step further. For example, the New York Performance Standards Consortium, a group of several dozen secondary schools (now expanding to other states), has received a state-approved waiver allowing students to complete a graduation portfolio in lieu of some of the state Regents Examinations. This portfolio includes a set of ambitious performance tasks: a scientific investigation, a mathematical model, a literary analysis, and a history/social science research paper, sometimes augmented with other tasks like an arts demonstration or analyses of a community service or internship experience. These meet common standards and are evaluated on common scoring rubrics. More recently, New Hampshire introduced a technology portfolio for graduation that allows students to collect evidence to show how they have met standards in this field. Portfolios at lower grade levels, also scored by teachers in a moderated fashion, were used statewide in Vermont and Kentucky in writing and mathematics.

Examples of International Systems

Other countries with highly effective educational systems rely on a mix of measures that usually include classroom-based assessments of more complex academic tasks and exams that have open-ended essays and other item types that get at constellations of student knowledge and skill applied in a more holistic fashion. (See chapter 4, this volume.)

Examination systems in England, Singapore, and Australia, for example, have common features that can also be found in the International Baccalaureate system, used in more than one hundred countries around the world. Students typically choose the subjects or courses of study in which they will take examinations to demonstrate their competence, or “qualifications,” based on their interests and strengths. These qualifications exams are offered in vocational subjects as well as traditional academic subjects. Part of the exam grade is based on externally developed “sit-down” tests that feature open-ended essays and problems; the remainder, which can range from 25 to 60 percent of the total score, is based on specific tasks undertaken in the classroom to meet syllabus requirements.

These classroom-based assessments are generally created by the examinations board and are scored by local teachers according to common rubrics in a moderation process that ensures consistency in scoring. They may range from a portfolio-like collection of assignments, like the tasks required for England’s General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) exam in English, to single large projects that complement the sit-down test, like the science investigation required as part of Singapore’s high school science examinations. (See chapter 4.)

In Queensland, Australia, national testing occurs at grades 3, 5, 7, and 9, and the state offers a reference exam at grade 12. Most assessment is conducted through common statewide performance tasks that are administered locally, plus a rich system of local performance assessments developed at the school level but subject to quality control and moderation of scoring by a state panel. The Queensland Curriculum, Assessment, and Reporting Framework helps provide consistency from school to school based on the state’s content standards, called Essential Learnings, which include unit templates and guidance for assessments in each subject. These include extended research projects, analyses, and problem solutions across fields. (See table 10.1.)

Table 10.1 Queensland’s System of Assessments

| Presecondary Level | Senior Level (Grades 11–12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Curriculum guidance | Essential Learnings: Scope and sequence guides, unit templates, plus assessable elements and quality descriptors (rubrics) | Syllabi for each subject outlining content and assessments |

| External tests | National tests of literacy and numeracy at grades 3, 5, 7, 9; centrally scored | Queensland Core Skills Test, grade 12 |

| Locally administered performance tasks | Queensland Comparable Assessment Tasks: Common performance tasks at grades 4, 6, and 9; locally scored | Course assessments, outlined in syllabus; locally scored and externally moderated |

| Locally developed assessments | Local performance assessment systems; locally scored and externally moderated | Graduation portfolios; locally scored and externally moderated |

The kinds of tasks used are intended to develop students’ abilities to guide their own learning, which becomes deeper over time with repeated opportunities to engage complex tasks, and their teachers learn to incorporate this kind of work into the curriculum. Students are expected and supported to develop increasingly sophisticated skills that indicate college readiness. For example, there are two common tasks—one used in grade 7 in science and one expected of students at the senior level illustrating how students are expected to become more independent in managing scientific inquiry over time.

Within schools, groups of teachers develop, administer, and score the assessments with reference to the national curriculum guidelines and state syllabi (also developed by teachers). At the high school level, a student’s work is collected into a portfolio that is used as the primary measure of college readiness. Portfolio scoring is moderated by panels that include teachers from other schools and professors from the higher education system. A statewide examination serves as an external validity check, but not as the accountability measure for individual students (see chapter 4, this volume; see also Tung & Stazesky, 2010).

This type of assessment can be used as a reliable and valid measure because educators have acquired very similar ideas of what adequate performance on these papers and tasks looks like. In nations as varied as the Netherlands and Singapore, these shared mental models of student performance on tasks shape teacher judgments. These are developed from the earliest stages of teacher education and are reinforced by high-quality in-course assessments and grading practices based on scoring guides that are closely aligned with standards.

In such systems, the combination of training, moderated scoring, and auditing has allowed performance assessments to be scored at high levels of reliability, while they also offer a more valid method for evaluating higher-order thinking and performance skills (Darling-Hammond & Adamson, 2010). Where school systems have devoted resources to assessment at the classroom level and have invested in classroom-based performance assessors, teachers have developed deep expertise that translates into shared judgments and common mental models of what constitutes acceptable student performance on complex types of learning.

Instruction is guided and enriched by assessments that value deeper learning. Teachers’ capacity to teach for deeper learning is strengthened through the process of planning for curriculum and assessments, scoring student work, and reflecting collectively on how to improve instruction. Students work on these assessment tasks intensively, revise them to meet standards, and display their learning to parents, peers, teachers, and even future professors and employers. Policymakers can track general trends as scores from multiple measures are aggregated, reported, and analyzed.

WHY IS A SYSTEM OF ASSESSMENTS IMPORTANT?

A system of assessments is necessary to capture the wide range of skills that students must master to be successful in postsecondary school and beyond. Such a system can be critically important in a number of ways. A high-quality system of assessments can generate information for a variety of purposes without distorting classroom instruction. Assessment influences instruction, for better or worse, and most current state tests tend to ignore this effect or just hope for the best. Although not all test items can emulate high-quality learning experiences, a system that includes both traditional “sit-down” assessments and classroom-embedded assessments can more positively influence teaching and learning.

Furthermore, research has found that when teachers become experienced in developing and evaluating high-quality performance assessments, they are better able to design and deliver high-quality learning experiences because they have a stronger understanding of what kinds of tasks elicit thoughtful work, how students think as they complete such tasks, and what a quality standard looks like (see chapter 7, this volume). In many states that have used performance assessments in mathematics and English language arts, studies found that teachers spent more time on problem solving, mathematical communication, writing, and assignments requiring complex thinking (Stecher, Barron, Kaganoff, & Goodwin, 1998).

Rich performance assessments provide a vehicle for teachers to examine student work so they (and their students) may gain insights into how students learn in the specific content area and how teachers can facilitate improvements in this learning. Because they model worthwhile tasks and expectations, embed assessment into the curriculum, and develop teachers’ understanding of how to interpret and respond to student learning, the use of performance assessments typically improves instruction.

Right now, state tests in the United States are unable to perform these functions. Because they are typically limited to multiple-choice and short-answer formats, they provide little useful information to teachers about how students think and what they understand. Neither do they provide much insight to postsecondary institutions about how ready students are for college-level work or to prospective employers about work readiness or specific technical skills required for careers.

Current well-known status measures such as the SAT and ACT have modest predictive value but provide little actionable information. These tests have gotten better at specifying the knowledge and skills associated with particular score levels. However, they are not diagnostic of what students should do before or after the test to be more college ready. And because they do not measure skills like research, communication, or complex problem solving, they cannot indicate how well prepared students are in these areas that are critical for college success. The goal should not be simply to come up with better second-order measures when first-order measures of student work can be used directly, as they are elsewhere in the world. While the SAT and ACT can contribute to a system of assessments, educators should devote more of their effort to measures that can represent firsthand how well students can perform the actual tasks necessary for college success.

The consortia assessments plan to be more directly aligned with postsecondary readiness expectations in English and mathematics. However, because the Common Core State Standards represent only this subset of the full range of college- and career-readiness expectations, states that rely solely on admissions tests and the new CCSS assessments will have two overlapping measures of the same domain. They will not together capture all the important aspects of readiness, nor will they be sufficiently actionable to guide instruction.

A system of assessments model can offer greater insight into college and career readiness and flexibility by allowing states to assemble the set of measures they feel best gauge a wider and more complex range of knowledge and skills in ways that approximate how these skills will be applied in postsecondary settings.

Such a system might begin with an on-demand assessment of the new Common Core standards developed by one of the new multistate consortia—the Partnership for Assessing Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) or the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC). They would then strategically design a variety of ways to develop, value, and look at the full range of Common Core standards and, beyond those, many of the additional college- and career-readiness skills, including content knowledge beyond English language arts and mathematics, key cognitive strategies, key learning skills and techniques, and transition knowledge and skills, as illustrated in Figure 10.2.

Figure 10.2 Competencies to Be Developed and Assessed

The recently released report of the Gordon Commission on Future Assessment in Education (2013), written by the nation’s leading experts in curriculum, teaching, and assessment, described the most critical objectives of new assessments this way:

To be helpful in achieving the learning goals laid out in the Common Core, assessments must fully represent the competencies that the increasingly complex and changing world demands. The best assessments can accelerate the acquisition of these competencies if they guide the actions of teachers and enable students to gauge their progress. To do so, the tasks and activities in the assessments must be models worthy of the attention and energy of teachers and students. The Commission calls on policy makers at all levels to actively promote this badly needed transformation in current assessment practice. . . . The assessment systems [must] be robust enough to drive the instructional changes required to meet the standards . . . and provide evidence of student learning useful to teachers. . . . Finally, it is also important that assessments do more than document what students are capable of and what they know. To be as useful as possible, assessments should provide clues as to why students think the way they do and how they are learning as well as the reasons for misunderstandings. (p. 7)

Following this report, a group of twenty assessment experts put forth a set of criteria for high-quality assessments. (See chapter 1, this volume.) Recognizing that no single assessment can evaluate all of the kinds of learning we value for students and no single instrument can meet all of the goals held by parents, practitioners, and policymakers, these experts advocate for a coordinated system of assessment in which different tools are used for different purposes—for example, formative and summative and diagnostic versus large-scale reporting (figure 10.3). These assessments should assess higher-order cognitive skills as they will be used in the real world rather than through artificial proxies; be benchmarked against those of the leading education countries; use items that are instructionally sensitive and educationally valuable; and be valid, reliable, and fair, which includes being used in ways that support positive outcomes for students and instructional quality.

Figure 10.3 Relative Emphasis on Assessment Purposes

Source: Paul Leather, personal communication, September 3, 2013.

HOW MIGHT STATES DEVELOP SYSTEMS OF ASSESSMENT?

As states seek to develop systems of assessment, they will want to consider how to meet the needs of various stakeholders for useful information, beginning with students themselves—along with their teachers and families who support their learning—and extending to policymakers who need to know how to invest in instructional improvements at the school, district, and state levels. In addition, employers and institutions of higher education need to understand what students know and can do as they leave high school and enter college or the workplace. Critically important is that this information be meaningful for these purposes rather than a remote proxy and encourage productive instruction truly supportive of deeper learning that students will be able to transfer to new situations.

As they seek to develop new systems of assessment, states should:

- Define college and career readiness

- Evaluate the gap between the system as it now exists and the desired system

- Identify policy purposes for state and local assessments

- Consider a continuum of assessments that address different purposes

- Identify the information assessments need to generate for different users:

- Policymakers (state and local)

- Students and parents

- Teachers

- Higher education and employers

- Develop assessments that can provide a profile of student abilities and accomplishments

- Connect these assessments to curriculum, instruction, and professional development in a productive teaching and learning system

- Create an accountability system that encourages the kinds of learning and practice that are needed to reach the goals of college and career readiness

An example of one state’s well-considered approach to developing such a system is the plan currently under way in New Hampshire.

In New Hampshire and other states that work to produce more useful and informative assessments, there is an effort to integrate assessment with teaching and learning. As more open-ended tasks offer more information about how students think and perform, they are also more useful for formative purposes, although they can and should offer information for summative judgments as well. In a new system of assessment, we should be able to move from an overemphasis on entirely external summative tests to a greater emphasis on assessment that can shape and inform learning.

A CONTINUUM OF ASSESSMENTS

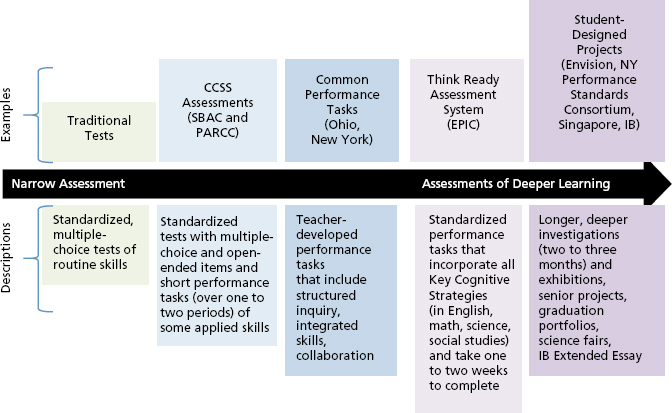

One of the key characteristics of a system of assessments is a continuum of options and methods for determining what students know and can do (figure 10.4).1 A benefit of this approach is that different types of information can be used for different purposes instead of trying to have one assessment address all needs. Performance assessments can be designed to gauge student growth on learning progressions, can be incorporated into proficiency determinations or end-of-course exams, or can be combined in a culminating fashion, as in the case of a graduation portfolio.

Figure 10.4 Assessment Continuum

These assessments can be thought of as existing along a continuum.2 At one end are the multiple-choice and close-ended items found in today’s traditional tests. These measure recall and recognition but not higher-level thinking skills or the ability to apply them. The tasks become more complex and extend over longer periods of time at each step along the continuum. They also measure larger and more integrated sets of knowledge and skill and provide insight into more cognitively complex aspects of learning and the application of knowledge to new settings and situations. As the more challenging tasks require greater student initiation of designs, ideas, and performances, they encourage and tap the planning and work management skills especially needed for college and careers.

The types of performance tasks or measures that are useful in a system of assessments can cover a wide span, from a single class period to a semester. They are generally graded by teachers (for their own students or in a system that is moderated across schools for other students) and can yield the kinds of information needed to help inform a range of decisions. Performance tasks may also be subject to some degree of external quality control. This can be accomplished by specifying task content, including creating common tasks at the state or district level, designing the conditions for task administration, managing how tasks are scored, and deciding how results are reported.

The most basic form of performance task may simply require a student to solve a multipart problem and explain the solution, write several paragraphs that analyze a piece of text or other evidence, or synthesize and reorganize information into a coherent whole. Even simple tasks assess knowledge and skills that cannot be gauged well with multiple-choice items. Teachers may devise these types of tasks themselves, pull them from curriculum materials, or access them online. They are generally closely tied to the content at hand and require only modest extrapolation and application of terms, ideas, and concepts being learned in class. An example of this type of task might be one in which students are asked to write a new ending to a story using a different literary style. More sophisticated in-class tasks might have students analyze which cell phone plan is most beneficial to them and their family based on their usage patterns (which students would estimate or have previously been told to bring to class) or by using average usage data they must gather online and interpret.

Next along the continuum of performance tasks are those that require at least some out-of-class work. These are incrementally more complicated because the teacher has to verify that all the work produced is the student’s own. Tasks of this nature might involve having students access information from US Census databases to answer specific questions about local conditions. The task could be measures of ELA knowledge and skills, math knowledge and skills, or a combination of the two. Part of the requirement would be a draft and then final version with edits and revisions. Tasks of this type can be developed by teachers individually or collectively, provided by states, or secured from online task banks. While some are teacher developed and not necessarily reviewed for their content validity or other psychometric properties, a growing number of short tasks have been carefully designed and thoroughly vetted to ensure they measure what they purport to measure and can be scored reliably. The following task is from the Ohio Performance Assessment Pilot Project:

In another performance task example, students in middle school math might be asked to use information about traffic volumes and flow to identify the best routes to take to get to various destinations and then to make recommendations on how to improve traffic flow overall or where to site a new hospital so that it is accessible but not in an area of high congestion. The first part might be completed in class individually, while the second might require additional work outside class followed by group work in class. Scoring might include a component score for correct use of mathematics, a separate one for problem-solving techniques, and a third for thoroughness of proposed solution.

A third example is a type of task that may take several weeks or even months of a semester. This is really best described as a project. Often it is the student who defines the focus of the project and is responsible for organizing the task and locating all the necessary information to complete it. The student may be expected to follow a particular outline or to address a range of requirements in the process of completing the project. The project may be judged by the teacher alone or scored by one or more other teachers in a moderated process that allows teachers to calibrate their scores to a benchmark standard.

For this type of project, a student or team of students might undertake an investigation of locally sourced foods. That investigation would require them to research where food they eat comes from, what proportion of the price represents transportation, how dependent they are on other parts of the country for their food, what choices they could make if they wished to eat more locally produced food, what the economic implications of doing so would be, and whether doing so could cause economic disruption in other parts of the country as an unintended consequence. The project would be presented to the class and scored by the teacher using a scoring guide that included ratings of the use of mathematics and economics content knowledge; the quality of argumentation; the appropriateness of sources of information cited and referenced; the quality and logic of the conclusions reached; and overall precision, accuracy, and attention to detail.

Finally, the fourth type of performance assessment can be classified as the culminating project. This type of demonstration is a means to gauge student knowledge and skill cumulatively. Taking the project one step further, students study one topic for a semester or even an entire year, applying what they are learning in their academic classes to help them work on the project. The results are presented to a panel that includes teachers, experts from the community, and fellow students. The culminating project may be interdisciplinary and generally includes a terminal paper and accompanying documentation, reflecting overall cognitive development and a range of academic skills.

This method of juried exhibitions is used in some examination systems abroad (e.g., in the Project Work task required as part of the International Baccalaureate and the A-level exams in Singapore, described in chapter 4) and, in the United States, by schools in the New York Performance Standards Collaborative and a number of networks.3 It allows students to communicate their ideas in writing, orally, and in other formats (e.g., with the use of multimedia technology or through products they have created) and to demonstrate the depth of their understanding as they respond to questions from others, rather like a dissertation defense. In Singapore, the project must also be collaborative, integrating another key skill.

A slight variation on this model is for the culminating demonstration to be based on a portfolio of work and not on one project alone. In this model, students integrate findings and observations from multiple projects, tasks, or assignments into a final demonstration that is organized around a topic, such as sustainability, public mental health services in the community, or a business plan for starting an enterprise chosen by the student.

Rich performance tasks can generate insight into other aspects of student learning skills and strategies. For example, teachers can report on student ability to sustain effort when confronted with difficult tasks; manage time to complete complex, multistep assignments; and work with others to improve both individual and group performance. This evidence of readiness for postsecondary educational opportunities and career pathways can be used in combination with scores on tests to provide a more balanced view of students’ abilities, including those critical to success, such as evidence of effective study habits, good collaborative skills, and resourcefulness.

This more varied information can come from performance tasks, where teachers observe the learning skills, techniques, and strategies students employ. Scoring guides can rate these types of learning skills along with content knowledge. Such performance task scores can be used to identify students with postsecondary potential who may not demonstrate their capacity fully on tests, but respond well to performance tasks as a means to express their knowledge and skills, their ability to learn independently, and their capacity to find resources when needed.

HOW CAN ASSESSMENT BE MADE USEFUL FOR STUDENTS AS WELL AS ADULTS?

A carefully designed system of assessments takes into account the varied needs of all the constituents who use assessment data: students, parents, and teachers; principals, superintendents, and boards of education; postsecondary officials and administrators in proprietary training programs; state education department staff, legislators, and governors; staff at the US Department of Education and in Congress; members of education advocacy groups; the business community; and many others. A system of assessments collates information from different sources to address a wide range of needs. The system does so in a way that results in a more holistic picture of students, schools, and educational systems. Such an approach does not waste or duplicate information or effort, but also does not rely a single source of data inappropriately.

Assessment to Guide Learning

Everyone agrees in principle that assessment can be instructive, but in practice, we tend to create a distinction between teaching and testing. Students can learn a great deal from assessments beyond where they stand in comparison to other students or the teacher’s expectations as expressed in a grade. A primary, though often forgotten, purpose of high-quality assessments is to help students learn how to improve their own work and learning strategies. Particularly in this era when learning-to-learn skills are increasingly important, it is critical that assessments help students internalize standards, become increasingly able to reflect on and evaluate their own work, and be motivated and capable of revising and improving it, as well as seeking out additional resources (human and otherwise) to answer emerging questions.

Assessments can serve these purposes when they are clearly linked to standards that are reflected in the rubrics used for scoring the work, when these criteria are made available to students as they are developing their work, and when students are given the opportunity to engage in self- and peer assessments using these tools. In addition, students develop these skills when assessments ask them to exhibit their work in presentations to others, where they must both explain their ideas or solutions and answer questions that probe more deeply, and then revise the work to address these further questions.

Through the use of rubrics and public presentations, students can receive feedback that is both concise and precise, as well as generalizable. They end up with a much better idea of what to do differently next time, particularly compared to what they do if they receive an item analysis from a standardized test or generalized comments from a teacher on a paper such as “nice job,” or “good point.” When students receive feedback of many different types from different sources, they can begin to triangulate among them to identify patterns of strength and weakness beyond just the specific questions they got right or wrong. This more comprehensive, holistic sense of knowledge and skills empowers learners and builds self-awareness and self-efficacy.

This approach to assessment assumes that students are a primary consumer of the information they produce, and it designs assessment processes that explicitly develop students’ metacognitive skills and give them opportunities for reflection and revision to meet standards. Not incidentally, these processes also support student learning by deepening teachers’ learning about what constitutes high-quality work and how to support it—both individually and collectively as a staff.

Assessment to Construct Student Profiles

In addition, assessments can support student learning by giving an overview of what students have accomplished, thus pointing to areas where students can take pride and further develop their strengths—with an eye toward college and career pursuits—as well as areas where they need to focus for further development.

Information from a range of sources can be combined into a student profile that provides additional data, such as teacher observations and ratings of students, student self-reports, and other measures such as internships and public service experiences. The profile is different from a transcript in part because it contains a wider range of information and because, where possible, it presents the information in relation to student aspirations and interests. In other words, students who wish to pursue health occupations would have evidence in their profile of the degree to which they are developing the knowledge and skills needed to enter this general field of study and pursue a career in it. Knowing something about student interests and aspirations provides a lens through which profile data can be interpreted and readiness determinations made more precisely. For students who do not know what they want to do beyond high school, a default profile can continue to determine readiness in relation to the requirements of general education courses at four-year institutions.

Why is a profile approach potentially important? Students can be expected to perform only as highly as their aspirations dictate. Getting students to engage in challenging learning tasks requires that they have some motivation or reason for doing so. A profile connected to their interests and aspirations helps show students why it is important to strive to achieve academically and develop the learning skills and techniques they will need throughout their career. Profiles are also a way to go a step beyond current college admissions processes that rely on grades and admissions tests scores primarily. More selective schools already review a wider array of data that looks in many ways like a profile. The admissions process seeks to learn more about student interests and aspirations and how these align with their preparation. This process is often called portfolio review. Why only the highest-achieving students should be encouraged to form and pursue goals and develop portfolios is not at all clear, especially at a time when all students are being urged to raise their expectations and engage more deeply in cognitively challenging learning.

Gathering and reporting information in this fashion is consistent with a research-based model of college and career readiness and leads to a full portrait of the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students need to succeed after high school. The profile provides students a clear understanding of the degree to which they are ready to pursue their postsecondary goals and also signals to teachers and schools a wider range of areas where student readiness needs to be addressed. While much of this information would be less useful for high-stakes accountability purposes, it is essential for students to have as they seek to become ready for their futures.

The following description is illustrative only; it is not meant to suggest the single blueprint for a profile system. Some of these sources would be appropriate as supplemental information; none should be the sole source of a decision about a student’s readiness. Work continues on identifying measures that can contribute to functional student profiles that combine multiple data sources in ways that yield insight into how well a student may succeed in postsecondary education or employment in a designated program of study or field.

An example profile could have the following types of measures in it:

- Common Core State Standards consortia exams

- Grade point average (cumulative and disaggregated by subject)

- Admissions tests (e.g., SAT, ACT) or sequence of Common Core or admissions-aligned tests (e.g., EPAS, Aspire, Pathways)

- Classroom-administered performance tasks (e.g., research papers)

- Oral presentation beyond consortia requirements and scored discussion

- Teacher rating of student note-taking skills, ability to follow directions, persistence with challenging tasks, and other evidence of learning skills and ownership of learning

- Student self-report on effort used to complete an activity and student self-report of goals and actions taken to achieve personal goals

- Student self-report of aspirations and goals

- Student postsecondary plans

This list ranges from rigorous tests to self-reports. Although the measures are not comparable and cannot be combined into a single score, they are useful because they offer insights into different aspects of a student’s abilities and goals.

In addition, the advantage of a profile approach, regardless of the precise measures selected to comprise it, is that students receive clearer guidance about where they stand in relation to college and career readiness, and they are then able to align their behavior with their goals. A wider range of behavior and skills is valued, including student goals, aspirations, and postsecondary plans, which strengthens student ownership of learning. Furthermore, schools and postsecondary institutions receive much more actionable information that can be used to improve student success, and state agencies and other stakeholders have a truer picture of how well schools are preparing students for college and careers.

Assessment to Inform Valid Decisions

When a decision is being made about an individual student, the information used must be valid. In other words, assessments should not be used for purposes other than those for which they were designed. For example, although the tendency to reduce the results of assessments to cut scores may be a convenient way to meet certain accountability needs (e.g., documenting how many students have achieved a particular level of performance) it is not a good way to make decisions about individual students. When a cut score on a test is used for a consequential decision about a student, it is a violation of a number of principles of good test design and appropriate score use, as specified in the Standards on Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education, 1999). This is particularly true in the case of high-stakes decisions about individual students. Cut scores generally, and a single cut score in particular, are not valid as the basis for high-stakes decisions about individual students. The higher the stakes are at the individual level, the more information is needed to understand a student’s knowledge and capacity. For example, if scores are going to be used to make decisions about graduation, remediation, program placement, admissions, or financial aid, more than a single test score is required. Additional sources of information on the knowledge and skills associated with readiness and success allow for more accurate interpretation based on evidence about the individual. Such data, including classroom-based performance evidence, are important to reduce the probability of making incorrect status determinations.

A system of assessments can provide the valid, reliable information needed for a variety of purposes, including important educational decisions. In fact, college admission at most four-year institutions in this country already takes multiple data sources into account, combining grade point averages with information about a student’s course choices, extracurricular experiences, test scores, essays, and sometimes interviews. In some cases when a student is on the margin, additional information from the application or a portfolio of work may be examined before a decision is made.

A system of assessments opens the door to a much wider array of measurement instruments and approaches. Currently states limit their assessment options because almost all assessment is viewed through the lens of high-stakes accountability purposes and the technical requirements associated with these types of tests. This makes perfect sense as far as it goes, but current assessments are not sufficient to bring about improvements in student readiness for college and careers: readiness depends on more than what high-stakes tests measure. A system of assessments yields a wider range of actionable information, much of it low stakes, that students and their teachers can use to develop the broad range of knowledge and skills needed for postsecondary success.

For example, teacher reports on students in the form of course grades are becoming progressively less reliable as grade point averages continue their thirty-year trend of increasing. Grades are supposed to be a measure of subject-area mastery, but they rarely are. They contain a mixture of information on performance, attitude, and ability to game the system. They do not include direct information on important aspects of student learning, such as the ability to sustain effort when confronted with difficult tasks; the ability to manage time to complete complex, multistep assignments; or the ability to work with others to improve both individual and group performance. Additional measures that capture this type of information are also needed. A system-of-assessments model can accommodate teacher ratings of student learning skills in addition to and separate from course grades. This additional information can conceivably yield valuable evidence of readiness for postsecondary educational opportunities and career pathways or, conversely, point out areas in need of improvement, areas not obvious from a course grade alone.

NEW SYSTEMS OF ACCOUNTABILITY

As states develop new systems of assessment, it will be important to develop new systems of accountability as well. As they do so, it is important to incorporate productive uses of new assessments while recognizing that assessments of student performance provide information for an accountability system, but they are not the system itself.

Genuine accountability can occur only when useful processes exist for using information to improve what schools and teachers do on behalf of students (Darling-Hammond, 1992–1993). Assessments and outcome standards alone cannot guarantee that schools will know how to improve or be able to make the changes that will help students learn more effectively. In fact, standards that are improperly designed can undermine accountability.

Defining Accountability

Accountability for education is achieved when the policies and operating practices of a school, school system, and state work both to provide quality education and correct problems as they occur. There must also be methods for changing school practices—even totally rethinking certain aspects of schooling—if they are not working well. Assessment data are helpful to the extent that they provide relevant, valid, and timely information about how individual students are doing and how schools are serving them. But these kinds of data are only a small part of the total process.

An accountability system is a set of commitments, policies, and practices that are designed to:

- Increase the probability that schools will use good practices on behalf of students

- Reduce the likelihood that schools will engage in harmful practices

- Encourage ongoing assessment on the part of schools and educators to identify, diagnose, and change courses of action that are harmful or ineffective

Thus, in addition to outcome standards that rely on many kinds of data, accountability must encompass professional standards of practice—how a school, school system, or state hires, supports, and evaluates its staff; how it makes decisions about curriculum and ensures that the best available knowledge will be acquired and used; how it organizes relationships between adults and children to allow the needs of learners to be known and addressed; how it creates incentives and safeguards to ensure that teachers and students are supported in their efforts and that problems are effectively addressed; how it establishes communication mechanisms between and among teachers, students, and parents; how it evaluates its own functioning as well as student progress; and how it provides incentives for continual improvement. These are the core building blocks of accountability. They reveal the capacity of educational institutions to serve their students well.

Even with the advent of more challenging and authentic measures of student performance, the creation of accountable schools and school systems will demand methods for inspiring equitable access to appropriate learning opportunities so that all students can achieve these learning goals. A complete view of accountability must take into account the appropriate roles of states and school districts in supporting local schools in their efforts to meet standards. This includes standards of delivery, including accountability for resources.

Accountability tools must address the barriers to good education that exist not only within schools and classrooms, but at the district, state, and national levels as well. For although schools themselves may be appropriately viewed as the unit of change in education reform, the structuring of inequality in learning opportunities occurs outside the school in the governmental units where funding formulas, resource allocations, and other educational policies are forged. In sum, if students are to be well served, accountability must be reciprocal. That is, federal, state, and local education agencies must themselves meet certain standards of delivery while school-based educators and students are expected to meet certain standards of practice and learning.

Elements of an Accountability System

This tripartite conception of accountability should include at least the following:4

- Accountability for resources (based on standards of delivery), encompassing:

- Adequate and equitable school resources (dollars, instructional materials, and equipment, including technology), allocated based on student needs

- Equitable access to curriculum, supported by policies that do not unnecessarily deny students access to programs of study from which they could benefit

- Access for all students to well-prepared teachers and other professional staff, based on policies that expand professional expertise and create incentives for equitable distribution of educators

- Accountability for professional practice, ensuring:

- Educator capacity that enables teachers to teach for deeper learning and administrators to understand and support this work at the school and district levels

- High-quality preparation, induction, and professional development

- Licensing based on evidence of teacher and administrator performance in supporting diverse learners to meet challenging standards

- Evaluation based on multiple indicators of practice, contributions to student learning, and contributions to colleagues that supports ongoing learning

- Schools designed to support personalization and deeper learning for students

- Processes that support continuous improvement for learners, teachers, and schools, including cycles of inquiry, goal-setting, and shared learning

- Educator capacity that enables teachers to teach for deeper learning and administrators to understand and support this work at the school and district levels

- Accountability for learning, based on:

- Multiple measures that are complementary and contribute to a comprehensive picture of the quality of learning in classrooms, schools, school systems, and states

- High-quality assessments that encourage and reflect deeper learning and authentic evidence of student readiness to succeed in college and in work

- Profiles of information about students, teachers, schools, and districts that move beyond a single cut score to a richer set of data that can provide indicators of accomplishment and grist for ongoing improvement

In the context of a comprehensive system of accountability, a system of assessments should strive to recognize and acknowledge that education is a complex process and that meeting goals for students, teachers, and schools requires indicators that draw from direct measures of the actual knowledge and skills associated with subsequent success. Most important, all of the elements of a system of assessments should be actionable and under the control of educators to improve. The more directly that educators can address the accountability measures and effect changes in student behavior associated with them, the more likely they are to do so.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

States interested in pursuing a system of assessments within a productive approach to accountability should consider the following action steps:

- Define college and career readiness comprehensively and note what will be involved with measuring all the components of the definition and supporting students to meet these goals.

- Realign other policy areas, program requirements, and funding to these goals, so that the state has a focused system of efforts that pulls in a common direction.

- Identify the information that is needed to determine if students are college and career ready based on this definition. Be sure to identify sources that are actionable—in other words, that students and teachers can act on to improve readiness.

- Determine the relationship between the definition of college and career readiness and school accountability needs. In other words, which aspects of the definition are most important for schools to be held accountable to address and which are important but may not necessarily lend themselves well to inclusion in an accountability system?

- Determine the professional learning, curriculum, and resource supports that schools and educators need to be able to provide a high-quality, personalized education for students that enables college and career readiness.

- Consider which opportunity-to-learn and educational process measures are needed to enable attainment of the outcome measures. Developing a plan to undertake the changes that may be needed in school funding systems, curriculum frameworks, and professional development supports—and launching work on these fronts—communicates that the state is serious about taking responsibility for its aspects of accountability.

- Develop, disseminate, and implement comprehensive standards (in areas beyond the CCSS), curricular frameworks, learning progressions, instructional tools and modules, exemplars of student work, and other materials aligned to the college- and career-readiness goals that support classroom practices that advance deeper learning outcomes. Develop teacher education and development standards and programs that enable educators to learn these practices.

- Support schools in developing approaches that offer all students opportunities to learn the new content in ways that can enable them to develop college- and career-readiness skills and all teachers opportunities to learn to teach to new standards. Consider the ways in which changes in the use of time and technologies may factor into these new approaches.

- Establish a clear framework for a comprehensive system of assessments aligned with CCSS and college- and career-ready outcomes.

- Assess the various ways in which information and accountability needs could be met by a variety of measures, including performance assessments, and integrate measures appropriately into curriculum development and professional learning opportunities.

- Ensure that these include opportunities for teachers to design, score, and discuss rich assessments of student learning.

- Consider how measures could be triangulated—in other words, how information from more than one source could be combined to reach a more accurate or complete judgment about a particular aspect of performance. Many important metacognitive learning skills, for example, can best be measured both as processes and products.

- Create a system of multiple measures for uses of assessments that result in decisions about students, educators, or schools. Where cut scores are proposed or may have been used, identify supplemental data that will reduce the misclassification rate when combined with a benchmark score. Develop profiles of information for evaluating and conveying insights about students and schools.

- Work with postsecondary and workforce representatives when developing new measures and implementing a system of accountability to ensure acceptance of the system and its measures of college and career readiness. Determine beforehand how data from the system will be used by postsecondary institutions and employers, and develop safeguards to avoid misuse of data, particularly cut scores. Define with postsecondary stakeholders how the results of rich measures of student learning can be best conveyed and used (e.g., digital portfolios, summary data supplemented by a taxonomy of work samples) and what kinds of profiles of information about students will be most useful and usable.

- Develop means for system learning to support continuous improvement at all levels of the system. These will include involving educators in the development and scoring of assessments so that they deeply learn the standards and have opportunities to share practice; means for documenting best practices and disseminating knowledge through online platforms sharing studies and highlighting exemplars; school study visits; conferences focused on the developing and sharing practices; feedback loops to students, educators, and schools about their work (e.g., through exhibitions, educator evaluation systems, and school quality reviews); and collaboration opportunities within and across schools and networks.

Research and experience make it clear that educational systems that can accomplish the deeper learning goals now before us must incorporate assessments that honor and reflect those goals. New systems of assessment, connected to appropriate resources, learning opportunities, and productive visions of accountability, are a critical foundation for enabling students to meet the challenges that face them in twenty-first-century colleges and careers.