Chapter 4. Helium: A Blockchain-Based Wireless Network

“ The first major [blockchain] breakthrough was bitcoin, which invented digital gold. The second was Ethereum, which introduced general purpose smart contracts. Helium presents the most ambitious new use case for blockchains we’ve seen since Ethereum.” – Kyle Samani, managing partner of Multicoin Capital 1

Helium was no longer just hot air.

As CEO Amir Haleem looked over the crowd of several hundred people who had filled Austin’s trendy La Condesa restaurant for the August 2019 Helium launch party, he was overwhelmed by the enthusiastic response of all these early users who were eager to build “The People’s Network.” After months of marketing and promotion, participants had come from all over Texas to pick up their Helium Hotspots. Helium was now a real shipping product, not just vaporware.

As Amir conversed with members of the crowd, he noted some were blockchain enthusiasts, some were Internet of Things (IoT) experts, and some were just geeks who wanted to be part of this groundbreaking experiment. These early users would be building a massive wireless network not on phone company towers, but on small wireless devices located in their offices and bedrooms. In return, they’d be paid in blockchain-based Helium tokens.

These little Hotspots, in other words, would be minting money.

Knowing that the strength of any blockchain project is user adoption—getting people to join your blockchain—Amir understood that this small but committed tribe of early adopters would be key to kickstarting the initial wireless coverage for the Helium network. This was a critical time to achieve critical mass, and Helium tokens were the hook.

As the party attendees returned home and began to plug in their Hotspots, Amir monitored the growth of the network over the next several days. As he saw each Hotspot blip to life on his digital map of Austin, each widening their circle of coverage, he felt a mixture of pride and relief that the dream he and his team had envisioned six years ago was finally becoming a reality.

One side of his marketplace—the network—was lighting up, but the other side was still shrouded in darkness. It was a classic technology problem: they were building supply, but would there be enough demand? In other words, would the company be able to find customers who wanted to use this new low-cost, lower-power wireless network, or would Helium ultimately tank?

The Helium Origin Story

Founded in 2013 by Amir Haleem, a championship videogamer, and Shawn Fanning of Napster fame, Helium’s original business idea was to create a giant wireless network, like a cellular network, but for the low-cost, low-power, low-bandwidth world of sensors. Before the Internet of Things (IoT) was even a thing, the two entrepreneurs saw that tiny sensors would soon be embedded in millions of devices: thermostats, fire alarms, kitchen appliances, inventory trackers, and maybe eventually your dog.

All these devices had one thing in common: they would need a low-cost, low-power wireless connection to the Internet. (See Figure 4-1.)

Figure 4-1. That’s a lot of things.

By 2014, Haleem and Fanning’s idea had evolved into creating a wireless network out of millions of “hotspots.” These hotspots would connect with hotspots around them, like repeaters that boost a wireless signal within your home, creating a kind of decentralized mesh network. Instead of the cell towers of centralized phone companies (large and expensive), a network of volunteers would host mini cell towers that connected to each other (large and inexpensive).

The idea of a “decentralized network” was taking hold in Cuba, where citizens were fed up with the slow and expensive Internet service provided by the state-owned telecommunications company. With a do-it-yourself work ethic, citizens formed a grassroots “Street Network,” eventually known as SNET, hosted by a huge network of volunteers who set up and maintained wireless stations from their homes and apartments across the island.2

But that was Cuba; this was the United States, where Internet service was already cheap and fast. If they wanted to blanket the country with their own wireless network—a US version of SNET— how could they convince people to set up hotspots, much less install them in high windows or rooftops where they would get maximum coverage?

The company had a few other false starts, but the extra time worked in their favor. By 2016, their prediction had come true: there was an ecosystem of small devices that needed to connect to the Internet. Scooters. E-bikes. Lawn sprinklers. And yes, even your dog (or at least your dog collar). The Internet of Things was officially a thing.

They saw that the millions (soon to be billions) of tiny sensors had specific needs that were much different from a cellphone:

Battery life: measured in years, not hours

Size: small enough to fit on many devices (scooters, dog leashes, etc.)

Location tracking: without needing an expensive cellular connection

Long range: the ability to connect over entire cities

Encryption: secure enough to transfer sensitive personal data (the location of your pet or valuables)

The extra time worked in their favor in another way: as many television stations switched to digital, they were auctioning off their unused bandwidth spectrum. At the same time, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was opening up new wireless frequencies that didn’t require a license. As the entrepreneurs saw it, these devices would only need a slice of that spectrum, and there was plenty of it.

They had a model of what they wanted: a nationwide network of Helium Hotspots, which they came to call “The People’s Network.” But how would they get the people to build the network? How could they get these Hotspots to sell like hotcakes?

It was Fanning, the Napster creator, who first said it as a joke: “What if we could get these things to mine bitcoin?”

Solving the Chicken-or-Egg Problem

“By offering blockchain-based tokens, Helium incentivizes anyone to own a Hotspot and provide wireless coverage—so the network belongs to participants, not a single company. A network can be scaled much faster and more economically than if a single company tried to build out infrastructure.” - Dal Gemmell, Helium Head of Product Marketing

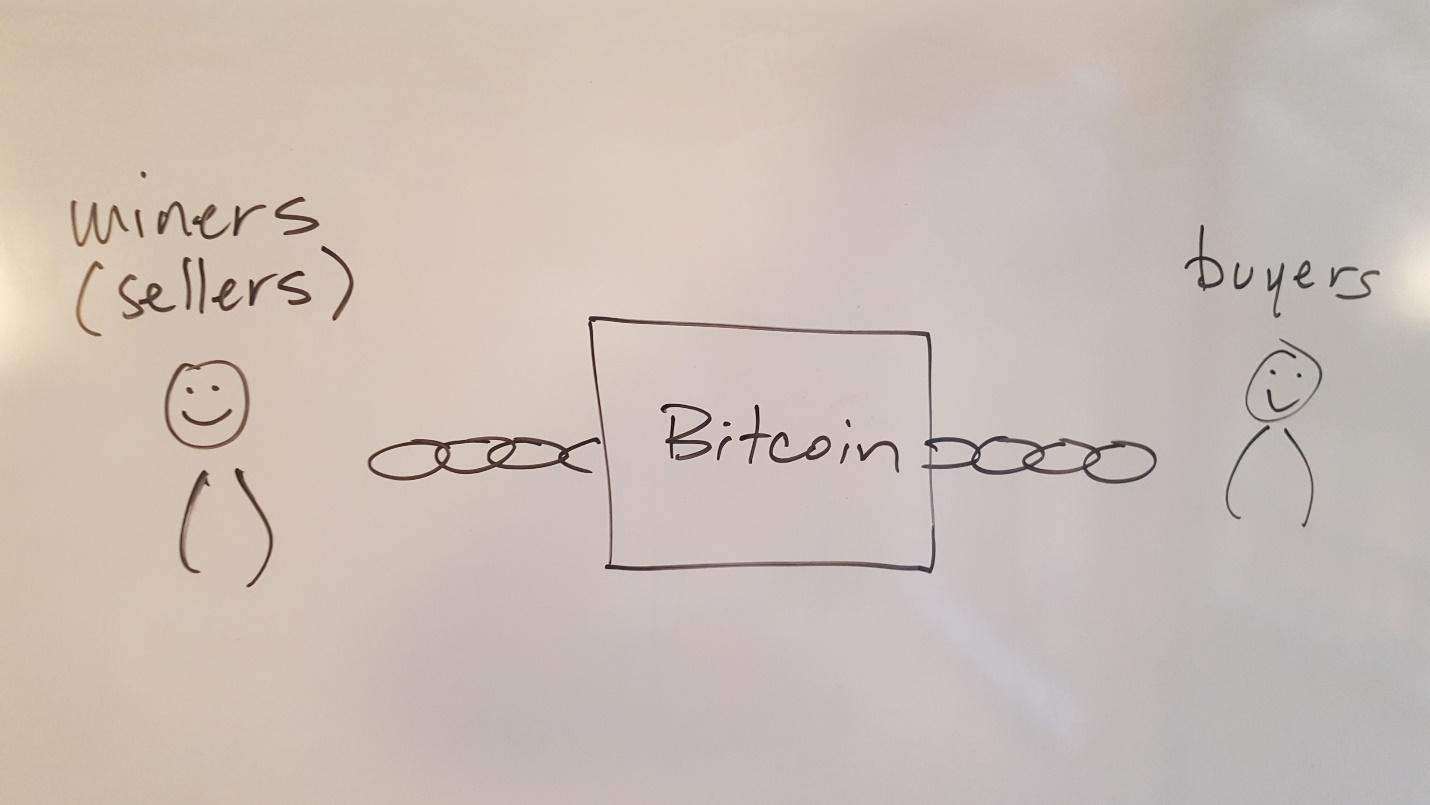

In their simplest form, blockchains use a two-sided marketplace: bitcoin, for example, has buyers and sellers. But how do you build a two-sided marketplace? Buyers can’t buy if there are no sellers, and vice versa. It is the classic chicken-or-egg problem: which comes first?

Chicken-Or-Egg Problem: When building a two-sided blockchain marketplace (buyers and sellers, or buyers and miners), which comes first, the chicken (miners) or the egg (buyers)? One solution: pay off the chickens.

Bitcoin began by attracting enthusiasts who built the network, who were rewarded in turn with small amounts of bitcoin. At first, they bought and sold this bitcoin from each other for fractions of a penny—but as their numbers grew, so did the network, and so did their net worth. As the price of bitcoin grew, more buyers attracted more sellers, and vice versa. (See Figure 4-2.)

Figure 4-2. All blockchains are multi-sided marketplaces.

The lesson: to kickstart their blockchain, Helium needed to reward the Hotspot owners. When users plugged in a Hotspot (i.e., when they created a new node on the network), they’d earn money. The company would create a blockchain-based token—the Helium token—to reward users for building the network, for holding their nodes.

Importantly, they called this activity mining.

Mining: Broadly speaking, the process of paying users small rewards for supporting the network. Like mining gold, mining should take “work” (like setting up and maintaining a Hotspot), and a reward is not always guaranteed (that reward may go to a nearby Hotspot instead of yours).

By framing Hotspot ownership as mining, Helium was creating a new mental model of money. Now it was in miners’ best interest to not only install Hotspots, but to configure them for optimal coverage, since they would also earn Helium tokens for the data that passed through each Hotspot. In fact, Helium Hotspots were an investment opportunity for landlords and businesses with multiple properties. (See Figure 4-3.)

Figure 4-3. How you solve the chicken-or-egg problem: you pay off the chickens.

Helium minted its own money—the Helium token—to motivate users to build out one side of the marketplace. The next problem was how to build the other side. Assuming these Helium tokens were worth real money, where would that money come from? In other words, who would pay to use this thing?

As it turned out, there were a lot of Things that would pay to use this thing.

An Internet for the Internet of Things

Package delivery. Rental returns. Supply chains. Energy metering. Temperature sensors. As the team envisioned from the beginning, all these Internet-connected devices were potential use cases for the Helium network. (See Figure 4-3.) For manufacturers of these connected devices, Helium had several advantages over existing solutions:

Operating cost: Where a sensor that connected to the 3G cellular network would cost a few dollars per month,3

a sensor connected to the Helium Network would cost a few pennies per month. For companies with millions of sensors, the cost savings were enormous.

Range: Bluetooth sensors only worked at short ranges, as anyone with a Bluetooth phone headset can attest. The Helium Network could provide connectivity several miles away from the nearest Hotspot.

Power: Where cellular chips kill batteries (think about how often you charge your cellphone), the Helium sensors could last several years.

Encryption: All communications over the Helium Network would have end-to-end encryption, meaning it was suitable for sensitive data. Even though ordinary users were funneling packets of data through their Hotspots, it was scrambled so they couldn’t read it.

Decentralization: With a traditional centralized telecom, your data plan gets more expensive every year (as users increase, they have to invest in more infrastructure). With the Helium decentralized network, it grows organically as more Hotspots are added, driving costs down.

Figure 4-4. Building out the buyer side of the marketplace.

After securing a $16 million round of funding, the entrepreneurs built a team of hardware, software, and blockchain experts, with a small business development team who began to search for prospective customers, including:

Bike and scooter rental companies. Rental apps for pedal bikes, electric bikes, and scooters were growing quickly. One of their challenges was the short lifespan of their vehicles, which were relatively expensive to maintain and replace. In some cities, users could “drop off” a scooter anywhere, leaving vehicles scattered across the city. Helium sensors could help rental companies keep track of inventory—as well as provide valuable usage data for peak rental times and neighborhoods.

Food and beverage delivery. Water delivery companies wanted monitoring devices on machines so they could quickly replenish water jugs, and eliminate unneeded deliveries from their routes.4

Any company operating vending machines or automated kiosks could use the same technology to notify them when an item was out of stock.

Smart trackers. Another emerging industry was smart pet collars, with a low-cost sensor that allowed owners to keep track of their pets, and easily locate missing animals through a downloadable app. This was potentially a huge market, since similar location trackers could be developed for children, the elderly, or those with special needs. Location trackers could also be used for package deliveries, rental cars, and anti-theft devices.

Wildfire detection. Where it isn’t fiscally feasible for traditional telecom providers to build the infrastructure to reach remote wilderness areas, a Helium network could be created to cover vast areas of forest for just a few thousand dollars. Hotspots connecting to sensors that monitor temperature (heat) or air quality (smoke) could easily detect and notify firefighters and forest rangers before these fires got out of control.

Agriculture. Sensors could guide farmers in which crops to grow, at the optimal time of year, in order to maximize yields. Helium sensors could collect data from automated irrigation devices and transmit it back to cloud-based control centers.5

Given the small profit margins generated by many farms, this data could be a matter of survival for family farms—and the future of agriculture.

With the growing list of use cases, the Helium team realized that a proprietary technology would probably get limited reception: customers would not want to be locked into a solution from a single company, and would likely work toward a global standard (like 3G).

So Helium made a critical decision: they would become the global standard. The company made a bold move, in the spirit of the decentralized blockchain, by open sourcing the design of the Hotspot, the sensors, and the software. Other companies would be free to manufacture their own Hotspots; anyone could build on the Helium Network. By opening up the technology to everyone, the company placed a big bet that Helium would take off. (See Figure 4-4.)

But first, the technology had to actually work.

Figure 4-5. The open-source chip for the Helium Hotspot, free for any company to manufacture.

The Hotspot Heats Up

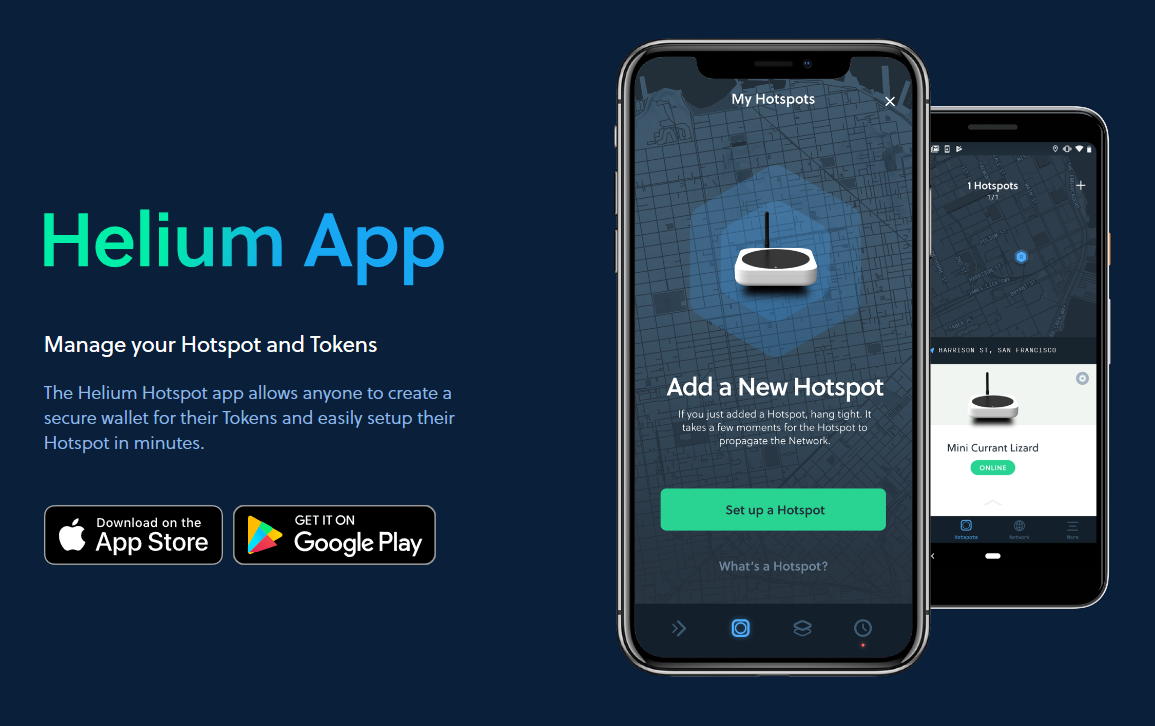

At the heart of this decentralized network was the Helium Hotspot, a small hardware device about the size of a smartphone, using a new long-range, low-power wireless protocol. The result was a $500 consumer-focused network node that was easy to set up and configure through a user-friendly smartphone app.

The company wisely hired product development experts who put a great deal of effort into the look and feel of the app. They wanted a seamless, user-friendly experience for configuring and maintaining Hotspots, so anyone could own one—not just hardware geeks and blockchain wonks. In addition to hiding the complexity of the network behind a simple interface, they designed the app (see Figure 4-5)to provide friendly, colorful, real-time stats on how much wireless traffic each Hotspot was routing.6

Figure 4-6. Easy to add, easy to monitor.7

Maximizing range was critical for making the network useable, because Hotspot coverage could be dramatically impacted by location, building materials, and radio wave interference. A Hotspot in San Francisco, for example, might have a range of about two to three miles, meaning Helium would need about 150 hotspots to cover the city. In rural areas, however, the range could extend out to ten miles.

To achieve this range, the Helium team had to develop a new wireless protocol called LongFi, a kind of long-range WiFi. It allowed any IoT device to connect to any Hotspot—up to thousands of devices per HotSpot—and transmit data back and forth over long ranges while maximizing battery life.8

But that wasn’t enough. The protocol also had to be decentralized, meaning it had to:

Set up without third-party assistance or verification;

Connect and send data without centralized validation;

Send payment from devices to Hotspots without intermediaries.

In typical networks, a centralized figure often provides access to the network (like your network admin). Helium’s decentralized wireless protocol (LongFi) and its decentralized hardware (the Helium Hotspot) allowed for unlimited growth of the network, without a central authority.

Even the sensors were decentralized. Let’s imagine a scooter rental company using the Helium network to track a fleet of scooters: it would receive a unique ID to be used across all its scooter sensors, with all Hotspots trusting that ID. This enabled sensors to “roam” without needing to re-authenticate: A rented scooter moving through a city, for example, would always stay logged into the network.

LongFi was built to transfer small packets of data, not for the high bandwidth requirements of smartphones or computers. But LongFi, unlike WiFi, didn’t require you to keep logging in. Any authenticated sensor on any Helium Hotspot could be trusted. As COO Frank Mong explained, the system is permissionless, meaning a username and password are not needed, as trust is stored on the decentralized blockchain.9

Permissionless: A confusing term that means “not requiring permission.” Permissionless systems do not require a username and password because the permission (i.e., the trust or authentication) has been stored on a blockchain.

The two-sided marketplace was coming together, with network “owners” on one side, and network “users” on the other. As Figure 4-6 shows, Helium was a set of open-source hardware and software standards that sat in the middle.

Figure 4-7. The software and hardware that runs the marketplace.

The team was building an entire ecosystem around the Helium token, the digital currency that would run this blockchain. But as with any economic system, there was quickly a lot of value at stake.

Helium Tokenomics

Miners hoped Helium tokens would rise in value, like an investment. But buyers wanted a fixed price. A scooter rental company, for example, wouldn’t use a technology that cost five cents per device this year, and ten cents per device next year.

The solution was to create two separate tokens: Helium Network Tokens (HNT) and Data Credits (DC). Where HNT could change in value (like an investment), DC would be a stable unit of purchasing power to use the network (like a currency). Think of these as mining tokens and usage tokens. (See Figure 4-7.)

Figure 4-8. The Tokenomics of Helium.

Here the company made an important decision: HNT would only be created when users did real “work.” Where most blockchain projects begin with a fixed amount of “pre-mined” tokens, HNT tokens would only be created when users set up Hotspots, validated other Hotspots, or had data transferred over their Hotspots.10

We call this idea token creation = value creation.

Token Creation = Value Creation (TC = VC): A best practice is to only create new blockchain tokens when some valuable unit of work has been performed (like validating a transaction on the blockchain). We do not recommend “pre-mining” tokens (creating a bank of tokens at the outset), or awarding tokens in so-called “airdrops” (free giveaways), as these do not encourage building long-term value.

On the other side of the marketplace, companies could use the Helium network by purchasing DC tokens, which gave them predictable costs and avoided crypto concerns like how the DC tokens would be classified by regulators. A Data Credit was true to its name: literally, a credit that allowed you to transfer one byte of data over the network, denominated in U.S. dollars.

The Helium team made another critical decision: Data Credits could only be acquired by burning, or deleting, Helium Network Tokens. This process was managed through a “ Burn and Mint Equilibrium”11

developed by Multicoin Capital. The fixed price of DC, based on market analysis, was set at $0.0001 per data fragment, or around $.24 to $.32 per megabyte.

Burning and minting: Two sides of the same virtual coin. Minting is creating a new token; burning is destroying it, or removing it from circulation. (Think of it like creating and deleting a file.)

As HNT was converted into DC through this burning process, those HNT were eliminated from circulation. Thus, Helium’s monetary policy was market-driven, i.e., based on who was actually using the system. Theoretically, the more people that used the Helium network, the more tokens would be removed from the system, thus making the existing tokens more valuable—and providing an incentive for more Hotspots. (See Figure 4-8.)

Figure 4-9. A “virtuous circle” of tokenomics.

In theory, as the demand for HNT tokens increases, the price of HNT should also increase. However, because Data Credits can’t be sold to other users, customers can be confident that DC will maintain their value.

In summary, Helium’s tokenomics were designed to create price stability for customers through the DC “usage token,” while still allowing miners to make money with the HNT “mining token.” Where the DC was non-transferrable, the HNT could be bought and sold freely, and perhaps later even sold on digital exchanges at a profit. Miners, of course, were hoping that the price of HNT would slowly rise up.

Funding and Team

Throughout this six-year journey, Helium pivoted several times, but always maintained the same problem statement: simplifying the process of connecting small, low-bandwidth devices to the internet on batteries that will last for years, with sensors that connect over miles. The company completed three rounds of venture funding:

Series A Funding – $16 million from Khosla Ventures, with participation from FirstMark Capital, Digital Garage, Marc Benioff, SV Angel, and Slow Ventures.12

Series B Funding – $20 million from GV (formerly Google Ventures), with participation from Khosla Ventures, FirstMark and Munich RE/Hartford Steam Boiler Ventures.13

Series C Funding – $15 million from Union Square Ventures, Fred Wilson, and Multicoin Capital.

One of the key takeaways from the Helium story is the importance of a consistent vision—both inside the company and with outside investors—even while the product pivots. This vision had to be both large and compelling enough to attract all the partners needed to build this massive ecosystem.

Internally, the company built small, agile teams around this vision in several key areas:

Distributed Systems Blockchain Team (6-7 employees)

Wireless Protocol Team (6-7 employees)

Mobile App Team (2-3 employees)

Hardware Manufacturing (largely outsourced, with 2 employees managing the vendor)

Business Development (4 employees, each assigned a geographical region)

The Helium business model was a combination of earning tokens from the network (motivation to make the network succeed), and offering services and support for organizations that want to use the open-source network (similar to Red Hat Software, which offers services and support for the open-source Linux). In this business model, Helium empowers the people to create a network that companies pay to use. Helium doesn’t own that network; the people who own the Hotspots do. The company was, in a sense, creating a network only to give it away.

But it all came down to getting network coverage: without a network of sufficient size, Helium would be nothing but vaporware.

The Launch

The company chose Austin, Texas as the site for the initial launch. As a rising technology hub, Austin had plenty of wireless technology early adopters and blockchain enthusiasts. It was a prime location for innovators, startups, and investors. And Austin had a number of local companies that were interested in piloting Helium (Lime, the scooter rental company, was already lined up).

The company determined it would take about 100 to 150 Hotspots to provide full coverage for the city. Within a month, they had exceeded that goal, with 200 Hotspots installed in Greater Austin—enough coverage for the entire city.

Thus, by offering a user-friendly product with blockchain-based rewards, Helium doubled its minimum goal of 100 Hotspots, convincing users to install enough $500 Hotspots to provide wireless coverage for the city of Austin.

Lessons Learned

Helium offers several best practices for technology leaders working on blockchain projects:

Stick to your knitting. Even as the product pivots, keep to your overarching principles (decentralized, open-source, permissionless) that are consistent with your vision for the project.

Focus on the front end. While good back-end blockchain developers are critical, be sure to hire a team capable of hiding the complexity of blockchain in a well-designed, user-friendly product.

Build open and scale quickly. As most blockchains will become a “winner takes all” or “winner takes most” scenario, lean toward making blockchain projects that are open and free.

Design tokenomics carefully. Be sure that tokens are only created when value is created, thinking through the needs of both sides of your marketplace, the chicken and the egg.

Keep it simple. In order to reach the mass market, your blockchain ultimately needs to be easy to explain and understand. Where it’s not possible to keep it simple, hide the complexity. (See Figure 4-10.)

Figure 4-10. Hide the complexity.14

Next Steps

“ The larger the network, the more valuable it becomes.” – CEO Amir Haleem

The telecommunications industry was ripe for disruption. Amir knew that once “The People’s Network” reached a critical mass, the blockchain-based network would become a powerful disruptive force, democratizing network access and distributing wealth to the masses.

Figure 4-11. Austin lights up.

As Amir watched new hotspots lighting up on his map of Austin, he pondered the company’s next move. (See Figure 4-11). How could the company rapidly scale “The People’s Network,” making sure both sides of the marketplace stayed in sync?

Should Helium seek additional IoT applications, including wearable technology and personal security? If so, on which of the many IoT applications should Helium’s business development team focus their efforts?

Should Helium consider listing its token on digital exchanges? This would increase demand for HNT, providing more liquidity for buyers and sellers. But listing on digital exchanges was expensive and time-consuming, and no one could predict how the market might price HNT.

Should Helium even be in the hardware business, or should the company partner with a manufacturer to take their open-source designs and produce Hotspots at scale, enabling Helium to focus on blockchain and software?

If you were the CEO of Helium, where would you float your next trial balloon?

1 https://decrypt.co/8179/helium-trial-balloon-a-new-peer-to-peer-wireless-network-goes-live-in-austin

2 https://www.wired.com/2017/07/inside-cubas-diy-internet-revolution/

3 https://www.link-labs.com/blog/cellular-iot

4 Haleem, Amir. “Entering the Next Phase of Helium.” Medium. The Helium Blog, August 3, 2019. https://blog.helium.com/entering-the-next-phase-of-helium-cfd7df3c6e3.

5 Haleem, Amir. “Entering the Next Phase of Helium.” Medium. The Helium Blog, August 3, 2019. https://blog.helium.com/entering-the-next-phase-of-helium-cfd7df3c6e3.

6 Dale, Brady. “Crypto-Powered IoT Networks Are on Their Way to Over 250 US Cities.” Yahoo! Finance. Yahoo!, September 24, 2019. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/crypto-powered-iot-networks-way-120050824.html.

7 http://www.helium.com.

8 Gemmell, Dal. “Learning about LongFi.” Medium. The Helium Blog, September 10, 2019. https://blog.helium.com/learning-about-longfi-4b7b36c9bf54.

9 Guida, Bill. “Helium | Longfi | Peer-to-Peer Wireless Network | IoT | Helium Token |.” YouTube.com. Bull Flag Group, August 13, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lW866pj6yQQ.

10 Haleem, Amir. “Entering the Next Phase of Helium.” Medium. The Helium Blog, August 3, 2019. https://blog.helium.com/entering-the-next-phase-of-helium-cfd7df3c6e3.

11 Samani, Kyle. “New Models for Utility Tokens.” Multicoin Capital. Multicoin Capital, February 13, 2018. https://multicoin.capital/2018/02/13/new-models-utility-tokens/.

12 Lawler, Ryan. “With $16M In Funding, Helium Wants To Provide The Connective Tissue For The Internet Of Things.” TechCrunch. TechCrunch, December 10, 2014. https://techcrunch.com/2014/12/09/helium/.

13 “Helium Raises $20 Million Series B Funding Round to Accelerate Smart Sensing Solutions.” Businesswire.com. Businesswire, April 25, 2016. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20160425005330/en/Helium-Raises-20-Million-Series-Funding-Accelerate.

14 http://www.helium.com.