Chapter 14

Mastering Tricky Situations

In This Chapter

Making journal entries: Where there’s a debit, there must be a credit

Recording new bank loans and loan repayments

Supporting the consumer economy (and recording hire purchase debt)

Tweaking the bottom line (whose bottom?) with expense adjustments

Matching income against expenses

The line between what an accountant does and what a bookkeeper does is a grey one. Some bookkeepers only do the bare minimum and leave the accountant to do the rest. Other bookkeepers prepare accounts that are damned near perfect, and all the accountant does is double-check the entries and make a few final adjustments.

This chapter is for bookkeepers who fall into the damned near perfect category, or even the completely perfect category: Bookkeepers who are ahead of their game and who want to create a set of accounts that’s as clean as a whistle. I talk about the very trickiest transactions that a bookkeeper encounters, such as how to record new loans, figure out hire purchase entries, make adjustments for prepaid expenses, journal provisions for employee leave, and a lot more.

Keen to hone your skills to a razor-sharp edge? Then read on . . .

Recording Journal Entries

Most of the transactions I describe in this chapter don’t involve a bank account, and instead involve a general journal, which is a special kind of journal, typically an adjustment, that transfers amounts from one account to another. If you use handwritten books or a spreadsheet, you write up these adjustments in a general journal ledger or a general journal worksheet; if you use accounting software, you record these adjustments using the general journal menu.

Unlike most other bookkeeping transactions, when you record general journals you need to have an understanding of debits and credits. If you feel at all befuddled about debits and credits, have a quick read through Chapter 3 and then return to this chapter.

If you look at other bookkeeping books, you may notice that no mention is made of GST and journal entries. You typically see journals with a format similar to Figures 14-6, 14-7 and 14-8, that only show account names, amounts, debits and credits. The reason for this format is that many journal entries don’t include GST, because they are an adjustment between accounts, rather than a payment or receipt.

In this chapter, in the instances where GST does come in to play, I show the journals in a different format, using a screenshot from an accounting software package. If you’re in doubt about whether or not a journal includes GST, always seek advice from your company accountant.

Plunging Into Debt

Global financial crisis, my foot. Despite more doom and gloom in the papers than even a nine-year drought could elicit, there seems to be no slowdown in the willingness for businesses to hock themselves up to the eyeballs in debt. After all, that flash BMW with the sweet-smelling leather seats is essential business expenditure . . .

Going into the red

Imagine the business that you’re doing the books for receives a bank loan, with the funds deposited directly in the business cheque account. Recording new loans can be daunting at first, but here’s how it’s done:

1. Create a new liability account called Bank Loan.

2. Record a new deposit in your receipts journal, allocating this deposit to your new Bank Loan account.

In MYOB, you do this via Receive Money. In QuickBooks, you do this via Make Deposits. If you're doing books by hand or using a spreadsheet, you simply record this deposit in your receipts journal and add a special memo.

3. Make sure you don’t include any GST on this transaction.

Why? Because a loan itself doesn’t include any GST, even though you may plan to use the loan to purchase something that does have GST on it.

Now imagine that this business receives another bank loan, but this time the funds go straight to a third party, such as a car dealer or a retailer of equipment, without touching the business cheque account along the way. You use a different tactic:

1. Create a new liability account called Bank Loan.

2. Record a general journal entry that debits an appropriate asset account and credits the Bank Loan account.

In MYOB, you do this via Record Journal Entry. In QuickBooks, you go to Make General Journal Entries. If you’re doing books by hand or using a spreadsheet, you add a new entry in your general journal.

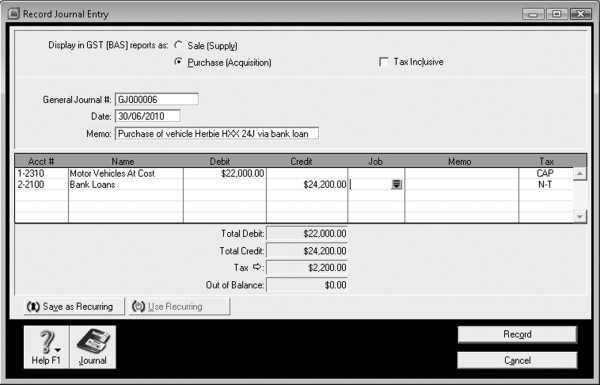

I show an example entry in Figure 14-1, where I purchase a motor vehicle for $24,200, including GST. In real life with a vehicle purchase, I would probably have on-road costs such as registration and insurance as well (I show this detail in Figure 14-4), but right now I’m keeping things nice and simple.

Figure 14-1: Purchasing a new vehicle via a bank loan.

3. Make sure you account for any GST on this transaction.

Unless you buy an asset second-hand from a private individual, most new assets such as motor vehicles and equipment include GST as part of the sale price. In Australia, use the ‘CAP’ tax code to indicate this purchase is a capital acquisition, and in New Zealand, use the standard ‘S’ tax code. (For more about tax codes, refer to Chapter 7.)

Aiming towards the black

An unhappy fact of life is that for every bank loan, there are loan repayments. So, how do you account for loan repayments in the books?

Easy. You record loan payments as a withdrawal from your bank account, and you allocate these withdrawals to the relevant liability account, usually called something like Bank Loan. (If you can’t see an account by this name, refer back to ‘Going into the red’ earlier in this chapter.) Loan repayments don’t have GST on them, so always code these transactions as non-reportable (Australia) or non-taxable (New Zealand).

By the way, if you use accounting software, see if the software features allow you to record loan repayments automatically. For example, I schedule the transaction for my car loan repayments so that my accounting software automatically records this transaction on the seventh day of every month.

Recording loan interest and fees

As a conscientious bookkeeper, you don’t only have to record loan repayments, but also loan interest and loan fees. Working from the loan statements, record a general journal for every interest entry or bank fee charged, dating this journal with the date that the interest or fee was charged.

Think carefully about GST reporting when recording loan interest or fees. In Australia, bank charges (with the exception of merchant fees) and interest expense are GST-free, which means you don’t claim GST on either expense, but you report these transactions on your Business activity statement. In New Zealand, bank charges and interest expense are classified as an exempt supply, which means you don’t claim GST on either expense, and you also don’t report these transactions on your GST return. (For more about tax codes, refer to Chapter 7.)

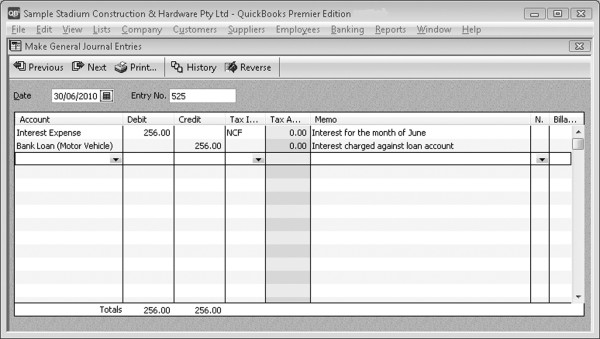

A typical general journal probably looks something similar to Figure 14-2. Note that I debit Interest Expense and Bank Charges and I credit the Bank Loan account. Remember that bank loans are liabilities, so crediting a liability account increases the outstanding balance.

Figure 14-2: Recording interest and bank fees charged against bank loans.

Copyright © 2010 Intuit Inc. All rights reserved.

When you finish all the journals, confirm your work. Generate a Balance Sheet report for the month that you’ve recorded interest payments up to (for example, if you enter interest expense transactions for January to March, generate a Balance Sheet as at 31 March), and check that the balance of the loan as it appears on the Balance Sheet matches against the bank statement.

If you find the loan on the Balance Sheet doesn’t match up against the bank statement, you’re best to try to reconcile this account in the same way as you reconcile any other bank account. Refer back to Chapter 11 to find out everything you ever wanted to know, and more, about reconciliations.

Working with Hire Purchase, Leases and Chattel Mortgages

Fast cars, shadowy corridors and an untrustworthy femme fatale — woops, I thought I was writing a film noir script for a minute. I’ll start again: Fast cars, shadowy corridors and . . . trade finance. Ah, to be a realist. In this section, I look at three additional kinds of finance options: hire purchase, leases and chattel mortgages. All three forms of finance are common in both Australia and New Zealand, and each one requires slightly different bookkeeping tactics.

Your starting point is always to get hold of the original paperwork, and double-check exactly what type of finance you’re working with. This paperwork is sometimes a tad confusing, so if you’re at all unsure, contact the bank, finance company or company accountant and ask for assistance.

Taking on a new hire purchase debt

Hire purchase is a loan allowing you to buy goods, such as equipment, vehicles or other assets on credit. You pay interest on this loan, and ownership transfers to you when the final loan payment is made.

In this section, I use the purchase of a new motor vehicle as an example for recording a hire purchase debt. I do this not only because motor vehicles are the most common thing that businesses buy on hire purchase, but also because this transaction is relatively complicated. In other words, if you can figure out how to record a hire purchase transaction for a motor vehicle, you can probably figure out any hire purchase transaction!

Your first step is always to get your hands on the original hire purchase agreement and make your way to where the figures are. The total amount of the debt typically has six elements:

The amount of principal being borrowed (from which a deposit has sometimes been paid)

Miscellaneous fees such as booking fees, dealer delivery fees, legal fees, valuation fees and stamp duty (stamp duty applies to Australia only)

Insurance and registration (new vehicles only)

Extras (roof racks, tow bars, window tinting and so on)

The total interest payable

GST (note that in Australia, GST isn’t charged on either stamp duty or registration)

In Figure 14-3, I show a typical extract from a hire purchase document summarising the purchase of a motor vehicle.

Figure 14-3: A typical summary from a hire purchase document.

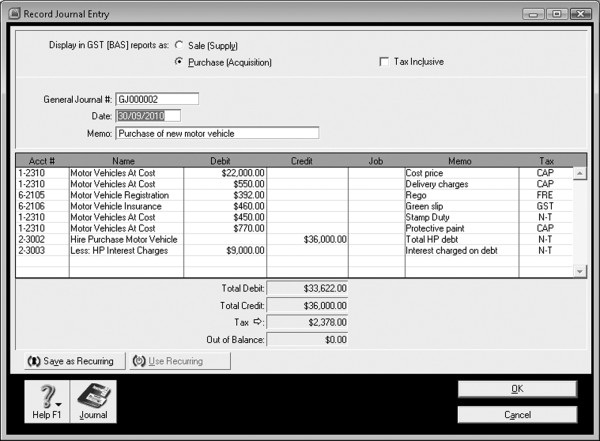

Figure 14-4 leaps straight into showing you what the journal for this transaction is. Here are a few tips explaining how this journal works:

I use the tax code of ‘CAP’ to show that the vehicle is a capital acquisition. In New Zealand, you don’t need to report capital acquisitions separately, so the tax code is just ‘S’.

With any new purchase, try to separate out capital costs (such as delivery and stamp duty) and expenses (such as registration and insurance).

You allocate the total amount of the hire purchase debt to a liability account called Hire Purchase plus a description of whatever it is you’re purchasing. (You’ll probably have to create a new account by this name.)

Look up the total interest that is charged on this loan, and allocate this total to a liability account called Less: HP Interest Charges. (You’ll probably have to create a new account by this name.)

If you do this journal entry for a business that reports for GST on a cash basis, you can’t claim all the GST on a hire purchase asset upfront. In this scenario, don’t use any tax codes that include GST on accounts you allocate to assets. Instead, show the value of GST on a separate line, and allocate this amount to your GST Paid account. See ‘Going for gold with GST adjustments’ later in this chapter for more details.

Figure 14-4: A journal entry showing the purchase of an asset using hire purchase.

Recording hire purchase payments

Most bookkeepers allocate hire purchase payments to an account called Hire Purchase Liability, and code this transaction as non-reportable (Australia) or non-taxable (New Zealand). This treatment is correct from an accountant’s perspective. The accountant then journals the total interest payable on the hire purchase once a year, debiting Interest Expense and crediting Hire Purchase Liability.

However, some business owners prefer to allocate hire purchase payments to an expense account called Motor Vehicle Hire Purchase. Although this treatment isn’t strictly correct — the payments are a repayment against a loan, and only the interest on this loan is an expense — you do get a more accurate reflection of month-to-month profitability with this method, especially in the earlier years of a hire purchase obligation, when both the interest and depreciation on the hire purchase asset are relatively high.

Of course, the most accurate method is to refer to the payments schedule provided by the finance company and split each payment between principal and interest expense. In practice, few accountants expect bookkeepers to go into this level of detail, and are fine to make an adjustment once a year to tweak the accounts.

Living it up with a new lease of life

A lease is a particular form of finance where a finance company buys an asset (such as a motor vehicle or new piece of equipment) on behalf of a business and then rents it back to the business. The business pays rent every month for an agreed amount of time, and then, if it chooses, at the end of this period buys the asset from the finance company for a reduced price.

Recording leases is usually pretty simple: You record the payment coming out of the business bank account, and allocate this payment to Lease Expense. You only have a couple of technicalities to bear in mind:

In Australia, some leases have a small amount of stamp duty included. Stamp duty doesn’t attract GST, so you need to split every lease payment transaction into two allocations: One for the taxable component, and another for the non-taxable component.

In some scenarios, such as a relatively short-term lease on an asset with a long life expectancy, accountants choose to show leased assets in the Balance Sheet. If this applies to the business you’re doing the books for, the accountant will provide you with a journal to record this asset in the books.

The first instalment of a lease sometimes includes additional amounts for registration and insurance. Find out what this first instalment includes and split it up correctly across the appropriate expense accounts.

Leases often involve a residual — a lump-sum payment payable at the end of the lease term that roughly equates to the value of the asset. If a business chooses to pay this residual, the asset transfers into its name. When (and if) this residual is paid, you allocate the whole amount to an asset account such as Motor Vehicles or Plant & Equipment, remembering of course that this residual payment almost certainly includes GST.

Signing up with a chattel mortgage

A chattel mortgage is a form of finance where ownership transfers to the purchaser right from the start (with hire purchase, ownership only transfers to the purchaser at the point that the final payment is made, and with leases, ownership only transfers to the purchaser if the purchaser chooses to pay the lump sum residual at the end of the lease term).

As a bookkeeper, you use the same method to record a chattel mortgage transaction as you do a hire purchase transaction (refer to ‘Taking on a new hire purchase debt’ earlier in this chapter) but with two important differences. First, when you record a chattel mortgage, you don’t record future interest charges, as I do in the last line of Figure 14-4. Second, you deal with GST differently: With a hire purchase debt, if you report for GST on a cash basis, you claim the GST back in small chunks with every repayment. With a chattel mortgage debt, regardless of whether you report for GST on a cash or an accrual/invoice basis, you claim back all the GST in one big lump in the first Business activity statement or GST return following the mortgage agreement.

Going for gold with GST adjustments

If you report for GST on an accrual or invoice basis, then you can claim the whole amount of GST upfront with the purchase of an asset via a bank loan, chattel mortgage or hire purchase. For example, the journal in Figure 14-4 shows GST of $2,378. Unless I make any adjustments otherwise, when I do my next Business activity statement (Australia) or GST return (New Zealand), this amount of GST is going to be included as a tax credit.

Things get thorny, however, if you report for GST on a cash basis and you finance an asset using hire purchase. Because you don’t actually own the asset yet when you have a hire purchase contract, you can only claim GST progressively with each payment. However, because each payment is effectively a mix of interest and principal (principal is the original cost of the asset in this case), you can’t claim GST on the whole payment. Instead, you can only claim GST on the part of the payment that relates to the principal. (You may need to refer to the hire purchase payment schedule in order to check the amount of GST charged.)

With this in mind, your first job is to make sure that the whole amount of GST doesn’t get claimed on the next Business activity statement. Assuming you already recorded a transaction in a format similar to Figure 14-4, where I recorded the full amount of GST, here’s what to do:

1. Create a new asset account called GST Yet To Be Claimed.

2. Do a journal entry that debits GST Yet To Be Claimed and credits your GST Paid account for the full amount of GST.

This gets the amount of GST out of your GST Paid account (which is right, because you can’t claim this GST yet), and stores it in an asset account, waiting for you to claim it back. Depending on how your accounting software reports GST, take care that this GST credit isn’t included in your activity statement.

Next, you have the tricky question of how to record your hire purchase repayments, and make sure you claim the full whack of GST that you’re due. I’m going to show you how to do this, using my original example (refer to Figure 14-3) of a hire purchase debt of $36,000, of which $9,000 is interest. I’m going to make this debt payable over three years (36 months), meaning repayments of $1,000 per month.

1. Look up how much GST is on the total hire purchase debt.

You can see from Figure 14-3 that the GST is $2,378.

2. Divide this GST by the number of repayments.

So, I’m planning to make 36 repayments. $2,378 divided by 36 equals $66.06 per month.

3. Multiply this amount of GST by 11.

This calculation gives you the taxable amount of each repayment. So, in my example, $66.06 multiplied by 10 is $726.61. This means that $726.61 of each repayment is taxable.

4. Deduct this amount from the total loan repayment.

My loan repayment is $1,000 per month. If I deduct $726.61 from this amount, I get $273.39. This amount is the amount that is non-taxable in each payment.

5. Record your hire purchase repayment, setting up this transaction to record automatically if possible.

In MYOB, transactions that record automatically every month are called recurring. In QuickBooks, the term is memorised. You can see how this transaction looks in Figure 14-5.

6. Check with the company accountant that your method of calculations is acceptable.

With this method, you take easy street and claim GST evenly over the life of the asset. However, some accountants prefer to be more precise, claiming the exact amount of principal and interest for each repayment, referring to a schedule of payments with each transaction. (The amount of interest declines as you pay off the debt, so in theory the split between principal and interest changes with every transaction.)

Figure 14-5: Recording hire purchase repayments for businesses that report for GST on a cash basis.

Copyright © 2010 Intuit Inc. All rights reserved.

Phew! You’re in the running for a silver medal. But if you want to go for gold, then you have one more job to do at the end of each year:

1. Calculate how much GST you have claimed back during the financial year on this asset.

In other words, look up all the repayments that you allocated to your Hire Purchase Liability account where you claimed GST. In my example, I claim back $66.06 GST per month, making for $792.72 for the year.

2. Debit your Hire Purchase Liability account and credit your GST Yet to be Claimed account for this amount.

In one fell swoop, I score a gold medal, reallocating the amount of GST I’ve claimed during the year against the Hire Purchase Liability account. What a wonder.

Tweaking the Bottom Line

Three accountants are being interviewed for a job. They’re all experienced, well-presented and amply qualified. So the HR officer poses the question (one that he personally, being a touchy-feely type, finds difficult to answer): ‘What is two plus two?’

‘Four’, replies the first candidate, quick as a flash. ‘Statistically anything between 3.9 and 4.1’, replies the second, with a nerdy twitch of the eyebrows. ‘Two plus two?’ counters the third, ‘I must ask a question in return — what would you like the answer to be?’

Accounting is not a science, rather an art form. I’m not talking tax evasion here, but rather I’m describing how the job of an accountant is often to tweak the figures, not only to get the best result from a tax perspective, but to match expenses against income and come up with financial statements that make sense. As a bookkeeper who’s on top of their game, it pays to understand the nature of these adjustments and also, in some situations, be able to make the journals yourself. So in the next few pages, I explain some of the most common types of adjustments that accountants (and bookkeepers) make.

Reallocating prepaid expenses

Prepayments are expenses that a business pays for in one lump sum (such as annual insurance or commercial bill interest), but which are really expenses paid in advance for months or even years ahead. The problem for you as a bookkeeper is this: If you record prepayments as an expense in the month when they’re paid, you understate the profit for that month but overstate it for the following months.

Don’t sweat. You can keep things sweet by using a series of simple journal entries to spread expenses evenly over the months or year ahead. Here’s your battle tactic:

1. Create a new asset account called Prepayments.

This account is always a current asset account.

2. Allocate the payment of the expense to this prepayment account.

For example, if you’re paying $12,000 (plus GST) for the insurance premium, you don’t allocate this expense to Insurance Expense, rather you allocate it to Prepayments. And remember, even though you’re allocating this payment to an asset account, don’t forget to claim the GST.

3. Divide the amount of the prepayment by the number of months it covers.

For example, if I pay $12,000 in advance for an insurance premium for the next 12 months, I divide $12,000 by 12 to arrive at $1,000 per month.

4. At the end of that month, record a journal entry that debits the expense account and credits the prepayment account for the monthly amount.

In Figure 14-6, I record a journal entry that debits Insurance Expense for $1,000 and credits Prepayments for $1,000.

Make sure you don’t claim any GST with this journal entry. You already claimed GST when you recorded the original payment (if in doubt, check back to Step 2), so you can’t double-dip.

Figure 14-6: Adjusting for expenses paid in advance.

5. If possible, set this journal up as a repeating journal so that it happens automatically at the end of each month.

Whether or not you can do this depends on what accounting software you’re using (if any). In MYOB software, repeating journals are called recurring transactions; in QuickBooks, repeating journals are called memorised transactions.

Accruing future expenses

An expense accrual is an adjustment for expenses that you haven’t received a bill for yet, but which the business has incurred. Many smaller businesses that report on a cash basis don’t bother with accruals. However, most larger businesses make accruals for expenses at the end of each financial year, and sometimes more often than that, so that they can accurately match expenses to the period in which they’re incurred. (For an explanation about cash versus accrual accounting, refer to Chapter 2.)

(By the way, a provision is pretty much the same as an accrual — being an adjustment for expenses or income not yet billed — but with the difference that the exact amount or the exact timing is uncertain. I talk more about provisions in the section ‘Figuring out leave provisions’.)

Here are some examples of accruals that accountants, or bookkeepers, often make:

Accounting and tax agent fees: In Australia, the accountant sometimes makes a journal entry on the last day of the financial year for the accounting fees that the business is going to incur for the year just gone.

Bills not yet received: Accountants sometimes make an accrual for bills expected from suppliers for work done in one financial year, but not received until the next.

Commission payable: Maybe the business pays commission to agents monthly, 20 days after the end of each month. In this case, the accountant may make an accrual at the end of each month for the commission payable.

Franchise fees payable: Typically, a franchisee pays the franchisor in the month or quarter after each reporting period. However, the accountant needs to make an accrual for franchise fees at the end of each month, so that the franchise expense belongs to the correct period.

Wages payable: If a business has a large payroll and pays employees fortnightly, and the financial year ends just before payday, accountants sometimes do a journal to recognise the expense of unpaid wages.

The reason accountants and bookkeepers make accruals is to meet the matching principle of accrual accounting, which aims to bundle together income and associated expenses into the same period. For example, by making an accrual for commission at the end of each month, you match the commission to the same month as the sales to which it belongs.

Enough of all this theory: If you want to do an accrual, how do you go about it? Hold my hand, I’ll lead the way:

1. Create a new liability account that describes the accrual that you’re about to make.

I like to be specific when describing accrual accounts, using names like ‘Accrual for Bills Not Yet Received’ or ‘Accrued Commission’, rather than vague descriptions such as ‘Accrued Expenses’.

2. At the end of each period (this can be weekly, monthly or quarterly), record a journal entry that debits the expense account and credits the liability account for the amount owing.

For example, if you pay sales commissions every month, you calculate at the end of each month how much commission is due, then you make a journal entry debiting Commission Expense and crediting Accrued Commission. You can see how this journal looks in Figure 14-7.

Don’t claim any GST with this journal entry. You can’t claim GST until you either receive a bill or make a payment.

3. When you pay this expense, allocate this payment to the relevant liability account, not the expense account.

For example, when you pay commission at some point during the following month, you allocate this payment to Accrued Commission, not Commission Expense. (And at this point, you can claim the GST if applicable.)

Figure 14-7: Making an accrual for expenses.

4. Check that the balance of your accrual account returns to zero, and if not, make an adjusting journal entry.

Sometimes when you finalise accounts, you realise that your accrual wasn’t completely accurate. For example, maybe you calculate commission to be $1,000 for a particular month, but the payment ends up being for $990. You need to make a final adjusting journal that debits the Accrued Commission account and credits Commission Expense for the remaining $10.

An alternative approach, and one that many accountants who only make journals once a year prefer, is to reverse accruals on the first day of the following month, recording a journal entry that debits the accrual and credits the expense. Then, when the expense occurs, this payment gets allocated to the relevant expense account.

Figuring out leave provisions

A leave provision is an entry in your accounts that allows for leave entitlements owing to employees. For example, if I have an employee who currently earns $52,000 per year, and she’s got four weeks of annual leave and two weeks of sick leave up her sleeve, making six weeks altogether, then I have a potential liability of approximately $6,000.

If you’re lucky, you may find that the responsibility for calculating and recording leave provisions falls to the company accountant, rather than you as a bookkeeper. But if you’re not so lucky — a likely scenario for a bookkeeper working in not-for-profit organisations — you’re going to have to get your head around this whole messy business. So here goes:

1. Print up a Balance Sheet for the last day of your financial year and highlight the balances of all the leave provision accounts.

Look for liability accounts called Provision for Long Service Leave, Provision for Holiday Leave and so on. Oh yes, and if your organisation makes journals for leave on a monthly basis, rather than an annual basis, then you print up a Balance Sheet for the month just gone, rather than for the year just gone.

2. Generate a report that shows how much leave employees are due.

Most organisations make provisions for annual leave and long service leave, but some organisations also make provisions for a whole swag of other entitlements such as sick leave, time-in-lieu owing, accrued rostered days off and so on.

By the way, if you need more info about calculating employee entitlements, scoot back to Chapter 10.

3. Chat to the company accountant about whether you need to adjust the leave figures at all.

Some accountants like to adjust leave figures, adding leave loading to annual leave, or adjusting long service leave accruals by calculating the probability of how many employees are going to stick around long enough to be eligible.

4. For each leave provision, calculate the difference between the Balance Sheet and the value of leave owing.

For example, if the leave report shows $5,000 outstanding in annual leave and the Balance Sheet shows $4,000, then the difference is $1,000. (Of course, if nobody has recorded leave provisions before now, then the difference is $5,000.)

5. Record a journal entry to adjust every provision account.

To increase the balance of a provision account, debit an expense account called Wage Provision Expense (create an expense account by this name if you don’t already have one) and credit the provision account. To decrease the balance of a provision account, debit the provision account and credit Wage Provision Expense. You can see how this works in Figure 14-8, where I increase the Provision for Annual Leave account by $1,000.

6. Check that the balances of your provision accounts are correct.

Even after a mind-numbing number of years doing this journal entry caper, I still sometimes have a brain freeze and muddle my debits and credits. That’s why I always check the Balance Sheet to see if the new balances of my provision accounts now match up with the leave reports.

By the way, most small businesses don’t worry about leave provision; not only are the journal entries somewhat tricky, but in most circumstance you can’t claim unpaid leave as a tax deduction anyway. (In Australia, you can’t claim unpaid leave at all; in New Zealand you can only claim unpaid leave as a taxable deduction if the leave is taken within 63 days of the end of the financial year.) Generally, only larger businesses, businesses that hire out staff and have a large payroll, as well as community and not-for-profit organisations, go to the trouble of recording leave provisions.

Figure 14-8: Making journals for leave provisions.

Separating private expenses from business ones

Many businesses, especially businesses that have a home office, end up with a bit of a jumble of business and personal transactions. Your job as a bookkeeper is to make sure that all legitimate business expenses get claimed, and that no personal expenses end up in the mix.

I’m going to give some examples from my own clients, where the bookkeeper needs to adjust for personal usage:

One client of mine claims 100 per cent of his motor vehicle expenses throughout the year. However, his log book shows that he can only claim 85 per cent of motor vehicle expenses, meaning that his bookkeeper needs to adjust for the non-claimable 15 per cent.

The same client runs his business from a home office and claims all electricity bills as a business expense. The bookkeeper later makes an adjustment, only claiming 20 per cent of electricity as a business deduction.

Another client of mine pays a cleaner every week from her own pocket for cleaning both her home and the office. She doesn’t claim any of this expense during the year, so her bookkeeper makes an adjustment once a year for 25 per cent of the total cleaning bill.

Adjusting expenses is easy. To adjust for an expense that has been overclaimed (such as a business claiming 100 per cent of a motor vehicle when it can only claim 85 per cent), do a journal that debits Owner’s Drawings and credits the relevant expense account for the amount that was overclaimed. For example, in Figure 14-9, the business owner has claimed $8,000 of motor vehicle expenses, claiming 100 per cent each time. I need to adjust for 15 per cent personal use, so I debit Owner’s Drawings (an equity account) for $1,200 and credit Motor Vehicle Expense for $1,200. You can also see that because GST was claimed against these vehicle expenses in the first place, I’m also careful to include GST in my adjustment.

To adjust for an expense that has been underclaimed, do a journal that debits the relevant expense account and credits Owner’s Drawings for the amount that was overclaimed.

Figure 14-9: Adjusting expenses to allow for personal usage.

By the way, I’m assuming in both these examples that you’re doing the books for a sole trader, because this is the kind of business where personal and business expenses most often become intertwined. However, if you’re doing the books for a partnership, you adjust Partners’ Drawings instead or, if you’re doing the books for a company, you make adjustments against the Directors’/Shareholders’ Loan account.

Bringing Income into Line

Although tidying up accounts usually involves making adjustments to expenses, you get some situations where you need to adjust income also. To close off this chapter, I talk about two situations where you may need to make income adjustments: The first is matching income to the correct period if you receive payment in advance; the second is recording dividend income correctly.

Shifting income received in advance

Occasionally businesses receive money in advance from customers. For example, I can think of two of my clients (one does bush regeneration and the other designs websites) who tend to get a flurry of advance payments just before the end of the financial year, with many clients paying thousands of dollars upfront for work that hasn’t even started yet. Another client, a not-for-profit organisation, survives on large government grants that are always paid six or twelve months in advance.

The name of the game, from an accounting perspective, is matching the income to the period in which it is earned.

1. Create a new liability account called Unearned Income or Income in Advance.

2. Figure out when the work that belongs to this income is going to take place, and when you want the income to show up in the accounts.

So, if you receive a government grant of $12,000 in advance for 12 months, you want to show $1,000 of grant income every month for the next 12 months. Or, if a customer pays $5,000 in June for a website design that you’re going to do in July and August, you want to show $2,500 as income in July, and $2,500 in August.

3. Allocate the whole amount of payment to Unearned Income.

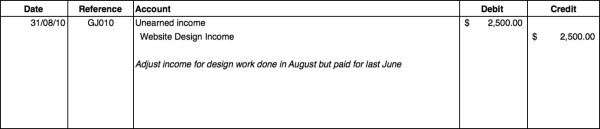

4. At the end of each month, make a journal entry that debits Unearned Income and credits the relevant income account for the amount earned.

See Figure 14-10 for how the deed is done.

5. At the end of the job, project, contract or whatever, check that the balance of Unearned Income returns to zero.

Make sure that when the income is earned and the deed is done, your Unearned Income liability account clears back to zero. Too often I go to check the accounts for a client and find amounts sitting in Unearned Income that have sat there for so long that nobody can even remember what they were for.

Figure 14-10: Matching income to the period when it is earned.

In this example, I show a ‘traditional’ approach for recording unearned income. However, if you use accounting software and the unearned income only spans one period — maybe you receive the money in June and then do the job in July — an easier approach is to generate a sales order to the customer, and apply customer prepayments against this order. Most accounting software is intelligent enough to realise that order prepayments automatically go to a liability account. When you later convert this sales order to an invoice, the software automatically transfers the deposit from a liability account to income.

Grossing up dividends

At first, recording dividend income seems easy (by dividend income, I mean dividends you receive from shares such as BHP or Telstra or whatever). You simply allocate the moolah against an income account called Dividend Income or something similar, and you’re done.

But here’s the rub: You actually get two kinds of dividends: Franked dividends, which are company dividends that include an imputation credit; and unfranked dividends, which are company dividends that don’t include an imputation credit (franked dividends are the most common of the two). Imputation credit is just a fancy word meaning tax credit, currently paid at a rate of 30 per cent in both Australia and New Zealand.

Occasionally, dividends may also include a credit for Withholding Tax. How you allocate this tax depends on whether the dividend is paid to an individual or a business entity — check with the company accountant if you’re not sure.

Almost all dividend statements show how much the imputation credit is worth, but the maths works out so that every 70 cents dividend paid includes a 30 cent tax credit. So if you receive a dividend for $70, you automatically receive an invisible tax credit of $30. (I say ‘invisible’, because you have nothing to show for this tax credit until tax return time.) Note: In some situations, you may receive a partly franked dividend, so I recommend that you always double-check the dividend remittance advice for the value of the tax credit.

Being the truly brilliant bookkeeper that you are, your job is to gross up dividends when you record them in the books, meaning that you allocate the gross value of the dividend to Dividend Income, and allocate tax credit to an asset account called Imputation Credits. The gross value equals the net amount you receive, plus the value of the tax credit.

Maybe an example will help explain what I mean. In Figure 14-11, I receive a franked dividend from Woolworths. The amount of the cheque from Woolies is $140, and the paperwork that comes with the dividend says I have a tax credit of $60. I do the following:

1. I enter the value of the cheque as the amount received (that’s $140).

2. I gross up the dividend by adding $140 and $60 together, making $200.

3. I allocate $200 to Dividend Income as a positive amount.

4. I allocate the tax credit (that’s $60) to Imputation Credits as a negative amount.

Voilà. My debits match my credits, and I have the feeling that the world is set to rights.

Figure 14-11: Dividends usually include imputation credits of 30 per cent.