Chapter 2

Creating a Framework

In This Chapter

Finding a home for every single transaction

Gathering materials with account classifications

Building foundations for your Profit & Loss report

Analysing income with a bird’s-eye view

Making everything just right with Balance Sheet accounts

The finished home — your first chart of accounts

If bookkeeping were just about doing your tax, the way you categorise information would be pretty simple. Income would be just one total, and most expenses would be lumped together, with only stuff like bank interest, rent and wages separated on reports.

However, your job as a bookkeeper is about much more than tax. You want to generate reports that explain exactly where your income comes from, which activities generate the most moolah, what the expenses are, how actual results compare against budgets, and lots more.

The way you categorise business transactions — in other words, the names of the accounts you use — provides the key to generating this kind of clued-up business reporting. Figuring out the accounts required takes a few smarts, because every business is unique and needs a custom-made list of accounts. But when complete, this list forms the framework for every business report.

In this chapter, I help you to build your own list of accounts. I wax lyrical about the differences between an asset and a liability, between income and expenses, and between earthlings and aliens. Discover how to set up a killer list of accounts that not only keeps the tax bigwigs happy, but helps this business flourish to boot.

Putting Everything in Its Place

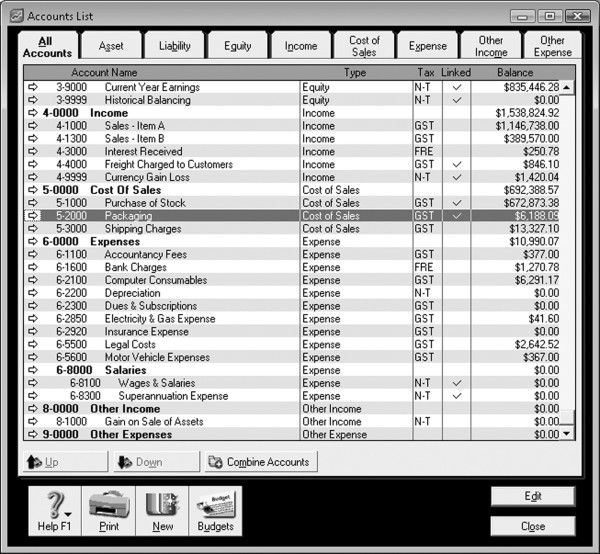

When I first worked as a bookkeeper, in the dim and distant past (but not before the dinosaurs, as my children claim), I worked with traditional handwritten ledgers. The cash disbursements ledger looked a little like Figure 2-1, with dates and amounts listed down the left-hand side, and a series of columns all the way across, with a different column for each kind of expense.

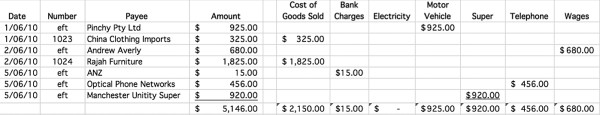

Regardless of how you do your books these days, the concept remains the same. If you work with handwritten books or even a spreadsheet, chances are that your books look pretty similar to Figure 2-1. Even with accounting software, the core information remains constant. Figure 2-2 shows the same transactions in QuickBooks, with a column for the date, the cheque number, a description, the allocation account and the amount.

In both Figure 2-1 and Figure 2-2, the choice of account is crucial. In Figure 2-1, the accounts are the headings that run along the top of each column. In Figure 2-2, the account appears in the bank register next to the name of the person being paid.

Figure 2-1: A hand-written cash disbursements ledger.

Figure 2-2: A bank register in QuickBooks.

Copyright © 2010 Intuit Inc. All rights reserved

Your job, as Bookkeeper-Chief-in-Command, is to decide exactly what these accounts should be. (After all, how can you record transactions if you don’t know where to put ’em?) The rest of this chapter gives lots of tips about how.

Classifying Accounts

A chart of accounts is the list of accounts to which you allocate transactions. These accounts describe what a business owns and what it owes, where money comes from and where money goes.

Accounts fall into six broad classifications:

Assets: Things owned by the business, such as cash, money in bank accounts, computers, buildings, motor vehicles and so on.

Liabilities: The stuff that keeps people up at night, such as credit card debts, supplier accounts, tax owing and bank loans.

Equity: The owner’s stake in the business, made up of money invested initially, or accumulated profit/loss built up over time.

Income: Income, quite simply, is money generated from sales to customers or returns on investments.

Cost of sales: What it costs in raw materials, supplies or production labour to make the goods that you sell.

Expenses: Business overheads, such as advertising, bank charges, interest expense, rent or wages.

Assets, liabilities and equity belong in the Balance Sheet. Income, cost of sales and expenses belong in the Profit & Loss. Knowing where transactions end up helps you to classify everything correctly, and with this in hand, creating financial statements is easy as pie.

I explore each of these account classifications in much more detail later in this chapter, discussing what kinds of accounts typically belong under each one.

Building Your Profit & Loss Accounts

How you build your Profit & Loss accounts depends on what kind of system you’re using. If you’re working with handwritten books or a spreadsheet, then the accounts are simply the headings of the columns where you list transactions. If you’re working with accounting software, you typically go to either your Accounts List (in MYOB) or your Chart of Accounts (in QuickBooks).

When I’m helping bookkeepers set up accounts for a business, I always start by making sure these accounts make sense. I don’t hesitate to add or delete accounts, change account names or re-organise the order of accounts. This way, I’m sure my clients end up with information that provides the maximum punch for the minimum pain. (Now I come to think of it, that maximum punch/minimum pain scenario sounds depressingly like my son’s high school study tactics.)

Analysing income streams

Most businesses have more than one stream of income. Maybe you’re a builder who earns money from new houses, as well as renovations and extensions. Maybe you’re like me and earn money from a combination of journalism, consulting and teaching. Or maybe you’re a musician who also does a bit of teaching on the side.

As a bookkeeper, think about the different sources of income a business generates. If you have fewer than five income accounts, have a think about how you could describe your income in more detail. Each major source of income needs a separate income account. For example, my friend who is a builder divides income into four accounts: Bathroom Sales, Kitchen Sales, Tile Sales and Renovations. This way, he generates regular Profit & Loss reports that reflect how his business generates revenue.

Accountants also like to talk about other income or abnormal income. Other income or abnormal income includes any income that’s not really part of your everyday business, such as interest income, one-off capital gains or gifts from mysterious great-aunties. Other income gets reported separately at the bottom of a Profit & Loss report.

Separating cost of sales accounts

Whatever kind of business you have, you probably have some expenses that directly relate to sales. In accounting jargon, expenses that directly relate to sales are called variable expenses. Expenses that don’t directly relate to sales are called fixed expenses or overheads.

Variable expenses are classified as cost of sales accounts. The idea is that when sales go up, cost of sales goes up, and when sales go down, cost of sales goes down. My consumption of chocolate brownies and my waistline function in just the same way.

The kind of expenses that you categorise as cost of sales accounts depend on the nature of the business concerned. Here are a few examples to help you figure out what’s what:

Manufacturing company: Cost of sales accounts include raw materials, electricity, production labour and factory rental.

Real estate agent: Cost of sales accounts include advertising, agent commissions and signage.

Retailer: Retailers usually have a single cost of sales account simply called Purchases. Here’s where you allocate any stuff you buy for reselling to customers.

Tradesperson: Cost of sales accounts include materials, equipment hire and subcontract labour.

Confused? If you’re unsure whether an account is a cost of sales account or an expense account, ask yourself this question: Does this expense immediately increase if sales increase? If so, chances are this expense is a cost of sales account.

Cataloguing expenses

Expenses are the day-to-day running costs of your business and include things like advertising, bank fees and charges, computer consumables, electricity, motor vehicle, rent, telephone and administration wages. Accountants also sometimes refer to expenses as overheads.

As a bookkeeper, make sure you tailor the expense accounts to the business concerned. On one hand, you don’t want to create too many accounts (I once saw a chart of accounts where there was a different expense account for every employee, and with over 25 employees this became ridiculous). On the other hand, if a business has a particular expense that makes up a large proportion of its expenditure, additional analysis can help.

Here are some expenses I usually include in a list of accounts:

Accounting Fees: I keep accounting fees separate from contract bookkeeping fees, so I can easily monitor what each service costs a business.

Bank Fees: Use this account for the regular transaction fees you get on your bank account. If you get charged merchant fees — which you will do if customers pay by credit card — you need a separate account for merchant fees.

Computer Expenses: I dump expenses for stuff like CDs, incidental software and printer ink into this account. I also often create additional expense accounts for Internet Expense and/or Website Maintenance.

Dues & Subscriptions: Here’s the spot for licence fees, professional memberships, magazine subscriptions and similar items.

Electricity & Gas: This is where you can catalogue your personal contribution to climate change.

Home Office Expenses: If a business operates from home, you may include expenses such as electricity, mortgage interest, rates and repairs in this account. (However, check with the accountant first regarding what home office expenses can be claimed.)

Insurance: If you have hefty insurance bills, I suggest you create a header account called Insurance Expense and, underneath, create detail or subaccounts for different kinds of insurance, such as Building and Contents Insurance or Public Liability Insurance.

I usually tuck the insurance for vehicles under the Motor Vehicles header, rather than the Insurance header, because when you report for tax, you need to report separately for motor vehicle expenses.

Interest Expense: Don’t get muddled between bank charges and interest. Bank statements always differentiate clearly between the two; all you have to do is be alert to the difference.

Motor Vehicle Expense: Again, maybe make a header account called Motor Vehicle Expense and, underneath, create subaccounts for fuel, maintenance, registration and so on.

Office Expense: You can use this account for squillions of different things, from printing and stationery to paper and pens, from a new office chair to a new filing cabinet. Just make sure you’re clear about the distinction between an expense and an asset — see the sidebar ‘When is an asset really an asset? later in this chapter for more details.

Rent Expense: Unless you work out of a home office, you almost certainly pay rent on an office or factory.

Salaries & Wages: If you have more than a handful of employees, consider creating detail accounts or subaccounts for the different categories of employees (see the sidebar ‘Under the microscope’ later in the chapter). For example, a restaurant may have three accounts; one account for kitchen staff, another for front-of-house staff and another for management.

Superannuation: In Australia, I suggest you create two superannuation expense accounts: one for employees and one for directors or business owners. In New Zealand, you need only one expense account for super, usually called KiwiSaver — Employer Contribution.

Telephone: If telephone expenses are high, create two accounts: one for office phone and the other for mobile phone.

Travel & Entertainment: If you travel overseas, remember to separate domestic and overseas travel. And if you spend money on entertainment, remember to trawl through the many thousands of pages of legislation to see what’s deductible and what’s not. (In New Zealand, the IR268 Entertainment Expenses booklet helps you figure out what expenses are deductible, and saves your accountant sifting through every entry. In Australia, the legislation is so complex you’re probably best to speak to your accountant for advice.)

By the way, accountants sometimes also use other expenses as an additional account classification. Other expenses are abnormal expenses that aren’t part of your everyday business, such as lawsuit expenses, capital losses or entertaining aliens from outer space.

Seeing Where the Money’s Made

Some businesses are actually several businesses bundled under the one name — like the newsagent who doubles as a post office and dry-cleaning agency, or the handyman who fixes your cupboard doors and also mows the lawn. To use accounting jargon, some businesses have multiple cost centres.

As a bookkeeper, part of the process of deciding what accounts you need involves considering whether this business also needs cost centre or project reporting. If so, you almost certainly require accounting software for this level of detailed analysis. The practicalities of how you effect this reporting depend on what accounting software you choose, but the principles are the same. By analysing how much money you’re making (or losing!) on everything a business does, you can fine-tune a business to maximise the chances of success.

By the way, don’t be tempted to create a swag of new accounts with a separate set for each cost centre. Instead, use a single set of accounts, but take advantage of the cost centre reporting in your accounting software.

In MYOB, there are two ways to report on cost centres: jobs and categories. Jobs are the most versatile feature, because you can allocate a single transaction to more than one job. Categories work better if you have separate bank accounts for each cost centre, or separate physical locations, or branches. Sometimes it works best to use both jobs and categories. For example, an architect client of mine has an office in Brisbane and another in Sydney. He uses the category feature in MYOB to identify which office transactions belong to, but he still uses the jobs feature to track profitability on each different project.

In QuickBooks, you can report by cost centre using the Customer/Job feature or the class tracking feature. Generally, the job feature works best for individual projects and class tracking works best for different company divisions. For example, builders often use the Customer/Job feature to keep track of profit on individual jobs, but use class tracking to categorise these jobs, separating new houses, project homes and home renovations into different classes.

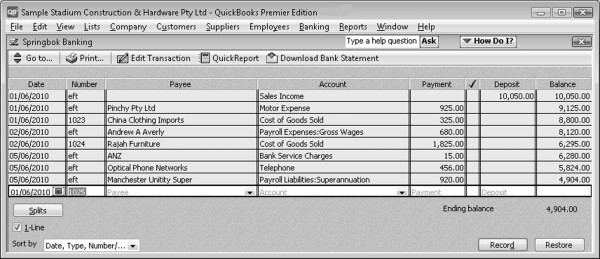

Whichever accounting software you use, the principle remains the same. You don’t just allocate a single transaction to an account, but you allocate it in other ways also. For example, in the screenshot in Figure 2-3, the transaction is allocated in several different ways: The Card field shows the name of the supplier; the Acct # column shows the type of expense; the Job column shows the projects; and the Category field shows the branch of the business that incurred the expense.

Figure 2-3: Accounting for cost centres.

Itemising Balance Sheet Accounts

If a business is already up and running, and has already completed the first year of business, an easy way to see what Balance Sheet accounts are required is to get your hands on last year’s Balance Sheet report from the accountant.

If a business is new, you can simply create new Balance Sheet accounts as and when you need them. However, read through the next few pages to get an idea of what accounts you may need to get you started.

Adding up the assets (ah, joy of joys)

So what’s an asset? Is it your pearly white teeth, your fine singing voice or your generous nature? None of these things, I’m afraid. The International Accounting Standards Board defines an asset as ‘a resource controlled by the enterprise as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the enterprise’.

Hmmm. My mind goes to mush when faced with this kind of talk, so I’m going to put it more simply: Assets are the good stuff, including anything you own, such as computers, office equipment, motor vehicles and cash.

Accountants like to classify assets according to how readily these assets can be converted into cash, typically using the headings current assets, non-current assests (also called fixed assests) and intangible assets.

Current assets

A current asset is anything that a business owns that can realistically be converted into cash within the next 12 months.

The kinds of things that get lumped into current assets include

Bank accounts and cash: Accounts that fall into this account type include petty cash, cheque accounts, savings accounts, term deposits and so on.

Short-term investments: No, I’m not talking about your latest love. I’m thinking of nerdy stuff such as shares or unit trust holdings.

Accounts receivable: Accounts receivable is the bookkeeping term for money that customers owe you. (Accountants sometimes refer to this account as trade debtors.)

Inventory: Another old-fashioned bookkeeping term, inventory is the word bookkeepers use for stock or raw materials that get sold to customers or assembled to make goods.

Prepayments: Smaller businesses don’t usually account for prepayments, but larger businesses make adjustments for things such as prepaid insurance, rent in advance or deposits paid to suppliers.

Work in progress: Work in progress includes jobs that have started but aren’t yet complete.

Non-current assets

This classification (also sometimes known as fixed assests) is for anything physical that you can touch, feel and see, but that isn’t readily converted to cash. Sounds kind of sensual but I’m talking about relatively mundane things such as office equipment, land and buildings, computers and motor vehicles.

Land and buildings: So if a business buys a block of land or a building, this is the account to choose.

Plant and equipment: Completely unrelated to potting mix, this rather agricultural sounding account includes stuff like new computers, telephone systems, machinery and tools.

Motor vehicles: Yep, that banged up rusty old heap is actually an asset, not a liability.

Accumulated depreciation: Yet another weird expression, meaning the amount the accountant has already claimed back on assets. I talk more about the convoluted workings of depreciation in Chapter 13.

Intangible assets

An intangible asset is something that is worth something, but that you can’t touch, smell or see. Intangible assets are usually not readily convertible into cash. (My husband assures me that his sense of humour is one of his intangible assets. At times, however, I reckon it’s more of a liability.)

The most common intangible assets are borrowing expenses, formation expenses, franchise ownership, goodwill and trademarks.

Borrowing expenses (Australia only): For example, if you were to take out a $50,000 loan over five years, and the bank charged a one-off fee of $1,000, the accountant may choose to allocate this expense to an asset account called Borrowing Expenses and amortise this expense over the period of the loan.

Formation expenses: Formation expenses usually relate to the cost of setting up a company. Because formation expenses aren’t tax-deductible, some accountants choose to show these expenses as an asset. (Other accountants write off formation expenses straight away, and make a tax adjustment in the final return.)

Goodwill: Goodwill is another example of an intangible asset. Many businesses don’t put a value on goodwill until they sell the business to someone else. At that point, goodwill becomes part of the purchase price and shows up on the Balance Sheet as an intangible asset.

Listing liabilities (oh, woe is me)

Liabilities are the stuff that keeps you awake at night. You know, bulging credit card accounts, supplier bills, GST owing, hideous bank loans and that unmentionable loan from your parents-in-law.

In the same way as accountants like to bundle assets into groups, they do the same with liabilities.

Current liabilities

A current liability is an amount owed by the business which is due within a one-year period. The kinds of accounts that sit under current liabilities include

Credit cards: I recommend bookkeepers think of credit cards in the same way as any other bank account. It’s just that the business owes the bank money, rather than the other way around. Strangely enough, simply ignoring credit cards and pretending they don’t exist doesn’t seem to work as a strategy.

Overdrafts: Again, you treat an overdraft in the same way as a regular bank account.

Accounts payable: Accounts payable (also called trade creditors) is the term for money that you owe to suppliers.

Other current liabilities: This category covers any other liabilities that are relatively short term, such as customer deposits, employee wages, tax owing, GST owing or short-term director loans.

Non-current liabilities

A non-current liability is anything you owe that isn’t due to be paid out within the next 12 months. The kinds of accounts that sit under non-current liabilities include

Hire purchase debts: Hire purchase debts are usually non-current liabilities because they’re payable over several years (although some accountants prefer to split hire purchase debts into current and non-current liabilities). Hire purchase liability accounts come complete with a partner, a strange account that goes by the name ‘Unexpired Interest Charges’ or ‘Future HP Interest Charges’. For more about this topic, check out Chapter 14.

Bank loans or mortgages: You know what these are. Seems that banks are always in on the act.

Accounting for equity

Equity is a fancy term for the ‘interest’ that a director or an owner has in the business, including both capital contributed and the profit or loss built up over time. The kind of equity accounts you need when bookkeeping depend on whether the business has a sole trader, partnership or company structure.

Out on your own (sole trader accounts)

Sole trader equity accounts include Owner’s Capital, Current Years’ Profits and Owner’s Drawings. As a bookkeeper, the only equity accounts you allocate transactions to are Owner’s Drawings, which is the account where you allocate any personal spending by the owner, and Owner’s Contributions, where you allocate personal contributions from the owner.

Sometimes, if a small business owner has only one bank account and uses this account for both business and personal spending, I create several Owner’s Drawings accounts. For example, a client of mine has one account called ‘Owner’s Drawings Mortgage Payments’, another account called ‘Owner’s Drawings Tax Payments’ and another account called ‘All Other Owner’s Drawings’.

Takes two to tango (partnerships)

With a partnership, each partner has both a Partner’s Capital account and a Partner’s Drawings account. At the end of each year, the accountant also uses a Distribution of Profit account for each partner. (The Partner Capital accounts, when added together, are equivalent to Retained Earnings in a company.)

As a bookkeeper, the only account you use on a regular basis is the Partner’s Drawings account.

Although partnerships don’t require an account called Retained Earnings, if you’re working with accounting software, you usually find this account is a default account that you can’t delete (at the end of each financial year, current year’s earnings ‘roll over’ into this Retained Earnings account). You can rename this account to become one of the Partner’s Capital accounts. The accountant can then provide a journal at the end of each year that adjusts the partnership capital accounts.

Aiming high (companies and trusts)

Companies typically have Retained Earnings, Current Year’s Earnings, Dividends Paid and Shareholder Capital as the equity accounts. Occasionally, companies also have reserve accounts, such as an Asset Revaluation Reserve.

Retained earnings are the income that a company holds onto, and doesn’t distribute to shareholders. Retained earnings (or losses) are cumulative, building up from one year to the next. When shareholders receive a profit distribution, you allocate this payment to an equity account called Dividends Paid.

Trusts have a similar equity account structure to companies, but have an account called Issued Ordinary Units or Trust Equity instead of Share Capital. When trust beneficiaries receive a profit distribution, you allocate this payment to an equity account called Trust Distributions Paid.

Don’t allocate any transactions to equity accounts for a company or for a trust unless instructed to do so by an accountant.

You may be wondering where to allocate personal spending by company directors. Either allocate personal spending to Director’s Wages (in which case you need to allow for wages and superannuation), or allocate personal spending to a liability account called Director’s Loan (in Australia) or Shareholder’s Loan or Shareholder’s Current Account (in New Zealand).

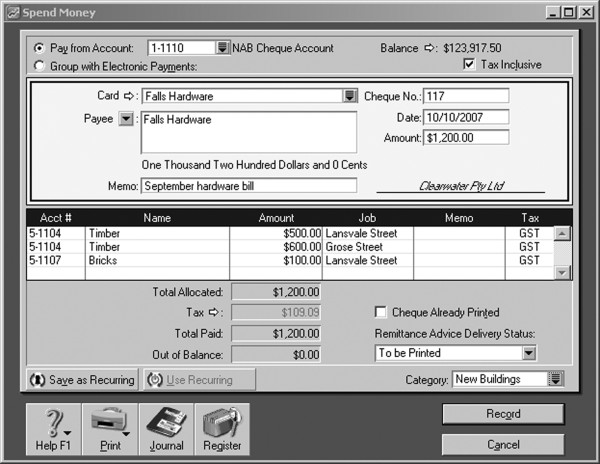

Building a Final Chart of Accounts

In Figure 2-4, you can see some of the accounts that make up the final chart of accounts for a wholesale business. The format of this chart of accounts is typical (listing account name, type, balance and so on), but remember that just as every business is unique, so every chart of accounts is unique also.

One feature with accounting software is that you usually get a choice of a few dozen templates when getting started. You can pick your business type from this list of templates and with three clicks of your heels have a complete chart of accounts ready to go. However, although a standard template seems like a quick way to get started, you may end up wasting hours customising this accounts list to suit. If the standard template isn’t a good fit, you’re best to start from scratch building your own chart of accounts.

Figure 2-4: A final chart of accounts, ready for action.