p.153

Strategy is dead. Long live strategic improvisation

Perplexity is the beginning of knowledge.

Kahlil Gibran

On 13 July 1985, just as Live Aid was beginning, I flew out of the UK aboard Aeroflot, to begin a tour of Russia lasting several weeks, spanning the whole continent. Despite the very strict rules on photography on the railway network, one of the more surprising sights I took away was spying a missile on a launch pad in the middle of Siberia as we ambled past on the Trans-Siberian Express! What was perhaps more revealing was the fact that the Soviet system of rigid five-year plans led to waste, hardship and bizarre Monty Pythonesque practices, such as having to keep the underfloor heating on in our apartment in Irkutsk at the height of summer. This required me to stand on one foot at a time in the shower and dance like a Prussian flamingo with matches under my feet! The experience of rigid plans that were totally out of phase with actual need was mirrored in trips to Bulgaria, Poland, Hungary and, worst of all, Romania, where central planning and manic control by Nicolae Ceausescu seemed to have left most people with basic subsistence but without resilience. Such things were not confined to the Communist world. In the early days of the European Union we saw butter mountains and other products of centralised long-term planning that was somehow disconnected with real life. You might well say that long-term thinking is dead in a disruptive business world, but what are the alternatives?

Strategy through the ages

Strategy is the process by which an enterprise examines its external and internal environments and makes choices that maximise its purpose, whether that is measured through profits or some other good, e.g. impact on society. Typically it involves some formal analysis, although some businesses develop strategy more intuitively, perhaps by experimentation in their marketplace. Typically strategy operates at three levels: The corporation; business unit level; functional level, e.g. HR strategy, marketing, etc.

p.154

p.155

There are several schools of thought on strategy. Here are some of the main thinkers in the field of strategy and their views condensed.

Competitive Strategy was epitomised by Michael Porter in his seminal book Competitive Advantage. Porter has now revised his views along the lines of our concept of SCA. Porter’s essential contribution was to look at the enterprise in systems thinking terms around five forces. A complex systemic interaction between:

• New market entrants who can disrupt your existing foothold on power simply by dint of their newness or perhaps by competitive pricing strategies and other approaches.

• Product and service substitution, which can also take a market by surprise. Quite literally, video killed the radio star!

• Customer bargaining power. Think of Tesco or Amazon dictating the terms of business and prices offered to their farmers for ‘grazing’ and their authors for ‘information grazing’.

• Supplier bargaining power with larger suppliers traditionally holding sway over the terms of business. Think of Tesco or Amazon dictating what the public can buy based on what they decide to stock in their stores.

• Industry rivalry with different players jockeying for position through different elements of the marketing mix from product to price, promotion, PR, etc.

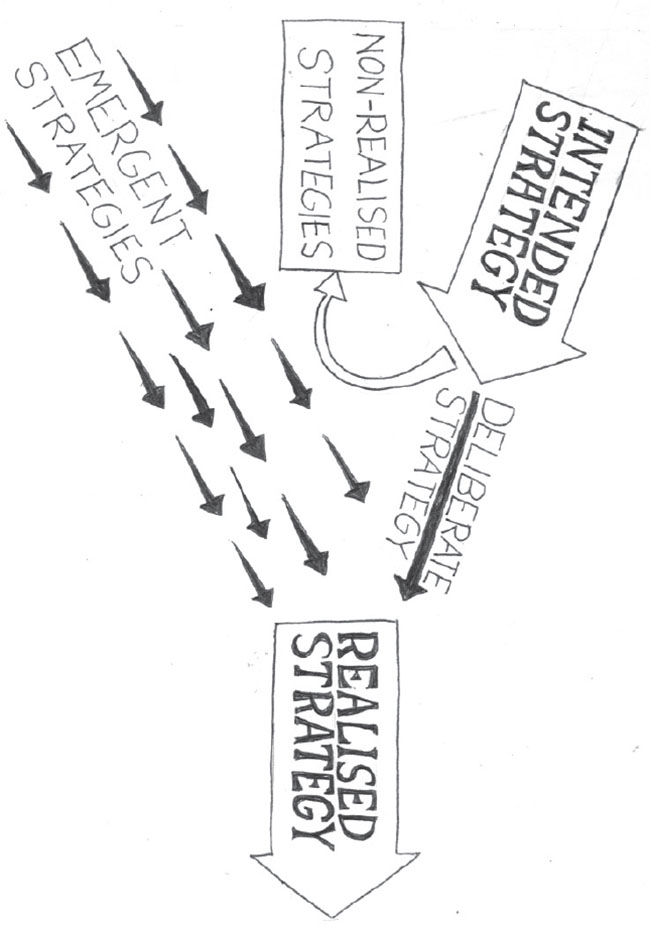

Porter’s thoughts fit in with the more general idea of deliberate strategy, which is analytical, structured and deterministic. Devices such as Vision and Mission Statements, SWOT analysis and MBO (Management by Objectives) are all products of a more deterministic approach to strategy. These are, of course, dreadfully attractive to those people who like to feel in control of their destiny and that of their enterprises.

Emergent strategy was the contribution made by Henry Mintzberg et al. Mintzberg and his followers made a distinction between deliberate strategy and emergent strategy. Emergent strategy results from the interaction of the organisation with its environment. Emergent strategies exhibit a kind of convergence in which ideas and actions from multiple sources integrate into a pattern. Authors such as Peter Senge tend to fit in with Mintzberg’s ideas in so far as they see a need for continual organisational learning. This seems increasingly relevant in a world where information is a major source of sustainable competitive advantage. For example, the founder of Wal-Mart built his stores close to his first store in rural settings rather than in big population cities, because it was easier for him to manage. He perhaps unwittingly stumbled upon a winning strategy. He found that there was less competition and people in the countryside would travel miles for discounted items.

p.156

p.157

Grant looked at strategy from the inside out, based on internal resources in what came to be called resource-based strategy, something that many smaller enterprises or voluntary ones operate by. Resources were defined thus:

• Valuable: A resource must enable a firm to employ a value-creating strategy, by either outperforming its competitors or reducing its own weaknesses.

• Rare: To be of value, a resource must be rare by definition. In a perfectly competitive strategic factor market for a resource, the price of the resource will be a reflection of its rarity.

• Hard to copy: If a valuable resource is controlled by only one firm it could be a source of a competitive advantage. More often it is bundles of resources that make a strategy hard to copy.

• Non-substitutable: Even if a resource is rare, potentially value-creating and imperfectly imitable, an equally important aspect is lack of substitutability.

Often these factors, when combined, lead to the notion of a USP or Unique Selling Proposition. Some niche businesses swear by this approach to strategy, others swear at it, believing that they control all the resources they need. A resource-based strategy can be a pragmatic step for enterprises that can combine elements of strategy in ways that build a unique position. If they can then brand that, their position can be sustainable.

Other views include strategy as agility and strategy as execution. Companies like Toyota, Nokia and Virgin pride themselves on being nimble and quick to respond. Nokia has mastered the chameleon principle, starting as a paper mill in 1865, moving through rubber boots to power generation and mobile phones. It remains to be seen how agile it remains under Microsoft’s stewardship. More provocatively, author and speaker Tom Peters suggests that strategy is execution. In other words, plans are nothing without action. This implies that strategy is made up on the ground and occasionally adjusted midstream in a chaotic business environment. Even large companies such as Unilever must consider the idea of flexible execution as customer moods and tastes change rapidly and brand loyalty is weaker. A relevant parallel to consider is the idea of improvisation in business and music. Here we examine the artform of improvisation in its many disguises and consider its application to a BBE.

p.158

The perils of free improvisation

As I write, we live in an age of greater spontaneity. A visible example of this is the recent sea change in our international affairs, where Donald Trump appears to have no time for rigid plans and stodgy committees, procedures and processes, preferring 140 characters rather than depth of character to make policy decisions. I must say I also have no appetite for petty bureaucracy in business. Yet Trump has adopted a pendulum ‘bipolar’ reversal, creating a war on plans and planning, where strategy is made on Twitter one day and reversed the next. In my experience, this free improvisation or ‘making it up as you go along’ approach to strategy is equally as unhelpful as long-range planning as exemplified by Shell in the industrial age and Communist Russia. To take a parallel lesson in music, in my time as a musician I have observed that freeform improvisation in music is often exhilarating for the musicians involved but it does not always attract or engage an audience. If I mentioned the musical artists Can, Stockhausen, Henry Cow et al., I am quite sure that only a few of you would have copies of their music in your collection. In extremis, free improvisation is an internally focused artform where the musicians are almost quite literally playing to themselves. Freeform guitar improviser Derek Bailey says that free improvisation is “playing without memory”.

In business, free improvisation, or what Professor John Kao calls jamming, is the realm of some start-up lifestyle businesses that are essentially serving themselves, sometimes with disastrous consequences. I must therefore take issue with Donald Trump over his free improvisation approach to strategy, although in doing so I may of course have missed the next wave. Time will tell. Undoubtedly we live in a disruptive world, but it does not follow that we should change our strategy as often as the ebb and flow of ladies’ hemlines in the fashion world, although it seems to be a modus operandi for strategy in the case of the 45th POTUS.

The perils of rigid plans

I must also take on the mighty Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of Antifragile and The Black Swan on one particular matter. In Antifragile, Taleb criticises the idea of what he calls corporate teleology or, simply stated, planning. He says that everything he learned in business school was babble, although he also mentions that he never bought any of the books or paid attention to his tutors! Citing the examples of Coca-Cola, which began life as a pharmaceutical product, and Nokia who started life as a paper mill, Taleb dismisses the notion of planning. For me this is just too much of a generalisation and I must therefore challenge his generally brilliant thinking in this particular area. Rigid plans are certainly problematic in a changing world, yet I frequently experience the poverty in the complete lack of planning in smaller enterprises and start-ups, who often subscribe to the view that ‘planning is for dummies’, sometimes because they lack the skills to do so or because they prefer to run a lifestyle business. Managing by drifting might be a lifestyle choice for some but it rarely leads to sustainable success. Some structure/discipline is usually needed to scale an enterprise without placing a stranglehold on that business, its owner and the people. In many cases the old adage ‘Fail to plan, plan to fail’ is borne out by extensive experience.

p.159

Taleb cites the example of AZT as one of the few pharmaceuticals that resulted from deliberate planning to justify a complete dismissal of the importance of planning. Yet the drug Zidovudine (AZT) was discovered in 1964 as part of a project to discover potential anticancer drugs. AZT’s activity in HIV/AIDS was only identified and then licensed some 22 years later, due to the routine screening that pharmaceutical companies give to their store of novel compounds. This is clearly not an example of deliberate strategy, except in the sense that the deliberate screening of compounds against new diseases is a logical and systematic approach used by all pharmaceutical companies in the search for remedies. I was proud to help bring the product safely to market in record time so I have some insights into the process.

Viagra (Sildenafil) was also not the result of a planned approach or a deliberate strategy. The compound was synthesised originally for expected activity in the area of hypotension but it demonstrated none. However, nurses noticed that it had side effects of penile erections during clinical trials. Scientists examining the data picked this up. It also needed considerable effort by a woman working in Pfizer’s marketing division to persuade Board members to embrace this new area of medicine, which was not taken seriously initially. It is a fantastic example of the systematic use of planning and analysis, without which we would not have Viagra. Taleb seems to misunderstand the improvisational nature of early stage drug discovery. We need to harvest the benefits of planning and agility to profit from a disruptive world, so let us next look at what can be learned in business from the field of improvisation in music.

Not only strategy but also improvisation

Bad improvisers block action, often with a high degree of skill.

Good improvisers develop action.

Malcolm Gladwell, Blink

Improvisation is a mystery. You can write a book about it, but by the end no one still knows what it is. When I’m improvising and I’m in good form, I’m like somebody half sleeping. I even forget there are people in front of me.

Stéphane Grappelli

p.160

The word improvisation is derived from lîla, a Sanskrit word for divine play, which conveys the meaning of improvisation in terms of the creation of newness in the moment. Another way to think about improvisation is the French word bricolage, which means making do with the material at hand, perhaps like the notion of resource-based strategy and our thoughts to come on the power of constraints in business. The bricoleur is an artist of limits, the nearest equivalent thought being that of do it yourself or DIY. Improvisation is a product of bricolage but when people talk of improvisation they often think of music, dance and comedy, rather less business. Yet all of us practise improvisation every day in conversation and in a sense much of life is improvised, where we are testing thoughts out with others, sometimes in an open search and on other occasions a closed one, where we are seeking a more limited set of options or answers. Improvisation in my professional life started at an early age. At the tender age of 25 I was sent on my first international assignment for six weeks to start up a new pharmaceutical factory in Indonesia. The culture shock was palpable to say the least, having barely travelled further than Calais on a ferry to France before this 17-hour trip to what seemed like another planet where I was warned that there were frequent shootings of foreigners! There was nothing in the way of what we would call mentoring or detailed planning and much of what I did to respond to this challenge could therefore be called improvisation. I remember the mixture of confusion and terror as I had a short meeting with the old grandee who looked after international support before I set out from the UK. Rather than giving me a business briefing, he reminded me to get my cholera and typhoid jabs done, but his best advice was that I should make sure I took a jar of Piccalilli and a bottle of Drambuie for Harry, the ex-pat factory manager. It turned out that these items were impossible to get in Jakarta. As I was about to walk out of the office, he added dryly “Harry does not really want you there. He thinks he can do the job himself”. Being thrown in at the deep end is one way to learn to improvise and I think I profited hugely from this and many experiences like it, but there are others . . .

Improvisation is ubiquitous in life and business due to the inherent entropy in the human condition. As pearls are formed when a piece of grit slips into an oyster shell we improvise spontaneously all the time from shopping to photoshopping, from sailing to emailing . . . and more deliberately during iterative design and new product development. Even in those jobs we might casually see as non-improvisational walks of life, for example surgery. Talking with surgeons it becomes apparent that, although they have a model of the body in their head from their training in anatomy and so on, each patient they are working on is slightly different to the model. Thus a skilled surgeon will improvise around their mental model to conduct their work with flair with obviously dramatic effects if they are successful or otherwise. Jacopo Martellucci undertook detailed studies on improvisation and surgery, concluding that surgery shares certain parallels with jazz improvisation, such as:

p.161

• simultaneous reflection and action;

• simultaneous rule creation and rule following;

• patterns of mutually expected responses;

• use of shared codes and signs; for example, people sometimes tap their head to signify that the band needs to move back to the motif (the ‘head’);

• continuous integration of the known with the novel; and

• a heavy reliance on intuitive grasp and imagination.

He states:

As surgeons, we spend endless hours tying knots with one hand, practising with a piece of string over the back of a chair, building homemade simulators, or looking for other creative methods to learn surgical tricks. As musicians, we practice scales until they become automatic.

Healthware enterprise Touch Surgery is helping surgeons develop sufficient deliberate practice such that their reliability when dealing with real surgery patients improves. CEO Jean Nehme explains that they use cognitive mapping techniques, AI and 3D rendering technology to codify surgical procedures. Touch Surgery also work with leaders in virtual reality and augmented reality, working toward a vision of advancing surgical care in the operating room.

Henry Mintzberg characterised improvisation in business as a kind of ‘guerrilla management activity’. He wrote on how managers cover up intuition with apparently rational activity. I have noted on many occasions that much great thinking in business is often ‘flimsy’ in so far as it occurs in the bath, the bed and the bar. Yet managers feel that they need to dress their ideas up in PowerPoint, spreadsheets or graphs in order to persuade hard-bitten decision-makers that an idea is ‘oven ready’ and ‘pressure tested’. In some enterprises, the culture allows and encourages speculation as a means of accumulation. For example, 3M allow time and money for employees to improvise by developing new ideas and products outside the company’s current bandwidth for many years. Google allowed employees to operate on a 70/20/10 basis: 70% of their time on designated work, 20% of their time on projects and innovations linked to that designated work, and 10% of their time on ‘free’ innovative activity. This has produced innovations, such as Google Maps and Gmail, although Google have reviewed this policy now. Yet the term improvisation is relatively poorly understood in business circles, as it implies ‘making things up’ when nothing could be further from the truth. Improvisation in music offers unique insights into understanding improvisation in business. I have met the good, bad and ugly of improvisers in my time and it is wise to learn from the best.

As Mintzberg points out, improvisation is a natural phenomenon in most business situations. Just consider this ‘day in the life’ story taken from a colleague’s direct experience as a change agent. The facilitator (hereafter called Jane) starts her day at 5.00 a.m. with a light breakfast. After all, she has a 50 km journey to her client’s site. On arrival, Jane finds that the e-mails she sent regarding room layout and other important details have been mostly ignored. Just as well that she is there by 7.15 a.m. Jane fixes the various items that seem unimportant to the event organisers (but wonders why they asked her to e-mail all of this in the first place). Anyway, she continues to ensure that everything looks ‘swan like’ (graceful on the surface, with great amounts of turbulence underneath) by the time the client arrives at 8.45 for coffee. The client (Michael) throws in a few new surprises. Of the 20 people invited, it turns out that eight of them have been sent to another equally important meeting. “No matter,” says Michael, “I’ve invited a collection of office staff that may well find the meeting interesting, even though they have no real interest in or knowledge of the topic under review. You did say it was important to have naive people in the room, and these people know nothing about the product or why we are here today.” It turns out that Michael did not even send them the invitation, which explained the reason for the event and what was expected by the end. Jane smiles and sighs inside. “Ah well, this is one of the reasons why they hired me”, she says to herself. Jane reminds herself of some useful knowledge she picked up when working in an improvisational theatre company. If an unplanned obstacle, such as a chair, appears on stage, the rule is to make sure that you ‘use the obstacle’. She quickly ensures she gets round the new people to introduce herself, the purpose of the day and what is expected of them before the start time. At the start, she asks for one or two members of the group to explain the purpose of the day to the newcomers and asks the newcomers to ask questions until everyone is at the same starting point. Not only has she ‘used the obstacle’, but the exercise has additional value, as some of the previously invited people had not read the invitation anyway! Turns out that two of the administrators have sociology degrees and had wanted careers in marketing and sales. Another secretary is an avid collector of garden gnomes and spends some time explaining their virtues to Jane while she is trying to set the projector up. We can learn well about improvisation from the arts so let us look at the relationship between order, structure and creativity, improvisation in business through the ears and eyes of music.

p.162

Business improvisation lessons from music

The very act of putting my work on paper, of, as we say, kneading the dough, is for me inseparable from the pleasure of creation. So far as I am concerned, I cannot separate the spiritual effort from the psychological and physical effort; they confront me on the same level and do not present a hierarchy.

Igor Stravinsky

p.163

Improvisation in music has been recognised ever since Mozart, Beethoven and Chopin’s activities showed that improvisation was viewed as an acceptable alternative to the performance of compositions from notation. A modern day example of structured improvisation in action is the music polymath Prince. Prince was highly disciplined about his work, using structure as well as improvisation to achieve a seamless performance, leading the band using a series of codes that signal musical changes which the whole band understands. For example, when he says “On the one, bass,” the whole band stops playing except the bass player on the first beat of the next bar. This requires extensive practice of a repertoire of hundreds of songs, from which Prince would draw down some 20–50 or so on a given night, sometimes without prior warning. I have interviewed several members of Prince’s musical collaborators, such as George Clinton, Marcus Anderson, Sheila E and his wife Mayte Garcia. One of the standout moments was an interview with Ida Nielsen, Prince’s bass anchor for his last six years. She had some practical observations to ground the subject of skilful improvisation at the highest levels of performance with masters of their art.

Ida is a living example of the idea of ‘deliberate practice’ as proposed by K. Anders Ericsson. Deliberate practice requires the systematic extension of one’s repertoire beyond one’s comfort zone. In our experience, some musicians reach a plateau of competence, due to re-rehearsing that which they already know. To master an instrument requires practice outside of the known regions of your competence. Ida related a story about learning ‘Donna Lee’ by bass maestro Jaco Pastorius that was way out of her competence range at the time. She pointed out that by setting the bar very high, eventually difficult pieces become easy. In my own case, I consciously switched from playing rock music to gypsy jazz in order to move my playing skill up a level through seeing and hearing things anew after I had plateaued in an existing genre. This concept applies in many fields of human achievement. The parallel notion in business is that of extending your competence beyond familiar behaviours or even familiar markets in order to master new approaches. The degree to which you decide to do this of course depends on your enterprise’s risk profile.

Ida respects and learns from great innovators in her field, like so many masters of their art, fusing their insights and inspirations into her own unique style. Her influencers include Marcus Miller, Victor Wooten, Bootsy Collins, Steve Bailey, Rocco Prestia, Jaco Pastorius and Esperanza Spalding. She cites Larry Graham as a key influence. Larry is credited with the invention of ‘slap bass playing’. This occurred out of the constraint of not having a drummer in the band, which required him to develop a more rhythmic way of playing the instrument. We explore the role that constraints and bricolage play in the improvisational process shortly.

Ida also spoke with me on the relationship between mastery and agility/improvisation when working with Prince himself. Ida had to learn more than 300 songs in order to have the flexibility to vary a given performance, sometimes on the fly. This is quite different from performing with most professional musicians, who prefer to hone a set and perform this as a set piece on all dates of a tour. This level of agility gave Prince and 3rd Eye Girl the ability to personalise their music to a given audience every night. To do this requires mastery at the individual and team levels, with everyone paying close attention to each other’s performances. This is IQ, EQ and SQ working in perfect harmony in the context of a team performance. Mayte also testified to the fact that Prince was a workaholic and a perfectionist in a counter-intuitive observation to what most people would think about people who are improvisers. Prince put much more than the so-called 10 000 hours of deliberate practice into his work in order to set himself free to improvise. His blend of order and creativity was exemplified down to the last detail. Mayte pointed out that all of his clothes were arranged in separate colours in his wardrobe. In their 10-year relationship, Mayte performed an estimated 129 shows, not including after shows, music videos, jam sessions and award shows and the work was of prime importance. Prince studied James Brown’s way of working and adopted a disciplined approach to the work:

p.164

We all worked for him. Whilst on tour I was not doing enough activity to keep in shape and Prince docked my pay and whilst he was very encouraging, he also expected discipline and the entire band knew that. It was a wake up call. Any dancer or ballerina that wants to be great knows that it requires hours of blood, sweat and tears to be your best. Nobody sees it.

Mayte Garcia

Prince’s sax player Marcus Anderson is a rare breed in so far that he is an improvising musician who is also classically trained. Sometimes one discipline drives out the other unless you are a master of your art, which Marcus is. He also gives testimony to the value of mastery or what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called the state of ‘flow’.

Although I can read music and therefore understand the ‘mathematics’ of jazz, the real skill of improvisation comes from using your ear/intuition, paying attention to the other band members, feeding off them and finding a flow that moves the group performance up to the max.

Marcus Anderson

The insights we can take away from Prince’s example is that improvisation is largely about ‘prepared spontaneity’. This aligns well with the idea of anticipation, which also has transferable value for businesses. Scott McGill, an improvisational musician who has worked with John Coltrane’s teacher talked a lot about anticipatory skills when improvising. McGill is also influenced by Ericsson’s findings. Ericsson noticed that the fastest and most accurate typists are the ones who can quickly anticipate the next move: “In sum, the superior speed of reactions by expert performers, such as typists and athletes, appears to depend primarily on cognitive representations mediating skilled anticipation rather than faster basic speed of their nervous system.”

p.165

Ericsson suggests that deliberate practice requires individuals to set performance goals beyond their current level of achievement, thus leading to repeated failures until eventual mastery is achieved. He also insisted that performing at the highest level depends on the quantity and quality of that deliberate practice. The concept of setting performance goals that are higher than one possesses but that are not too far from one’s present abilities agrees with other concepts such as Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is defined as the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers. If we are to swim rather than sink in the information age, we all need to:

1. Learn to stretch beyond our comfort zones and completely switch genres on occasion to improve our value and relevance in a changing world. You might wish to seek out a challenge in order to grow, even something you would naturally avoid.

2. Tolerate, learn from and even enjoy mistakes and occasional failures, recovering rapidly.

3. Learn how to improvise and ripen our ideas so that they produce ROI (Return On Innovation).

If you are to improvise, it follows that there will be occasional mistakes. Improvisation is also based on having certain rules (constraints) and freedoms and it requires us to embrace the unfamiliar (dissonance). We next explore these as the breakfast of champion Brain Based Leaders.

GROUND CONTROL

Deliberate practice

• Start by setting yourself a stretch goal that is within your ZPD.

• To learn skills more rapidly observe others who excel at your goal.

• Make incremental changes each time you practise and note what works and what does not.

• To move toward your goal more quickly, get feedback from a friend, mentor or coach or use video to improve your performance. Use an app or a diary to record your progress.

• Systematically work on weak areas, not by repeating them but by visualising ways to overcome them and then practising strategies to reach your goals.

p.166

The power of mistakes

Do not fear mistakes. There are none.

Miles Davis

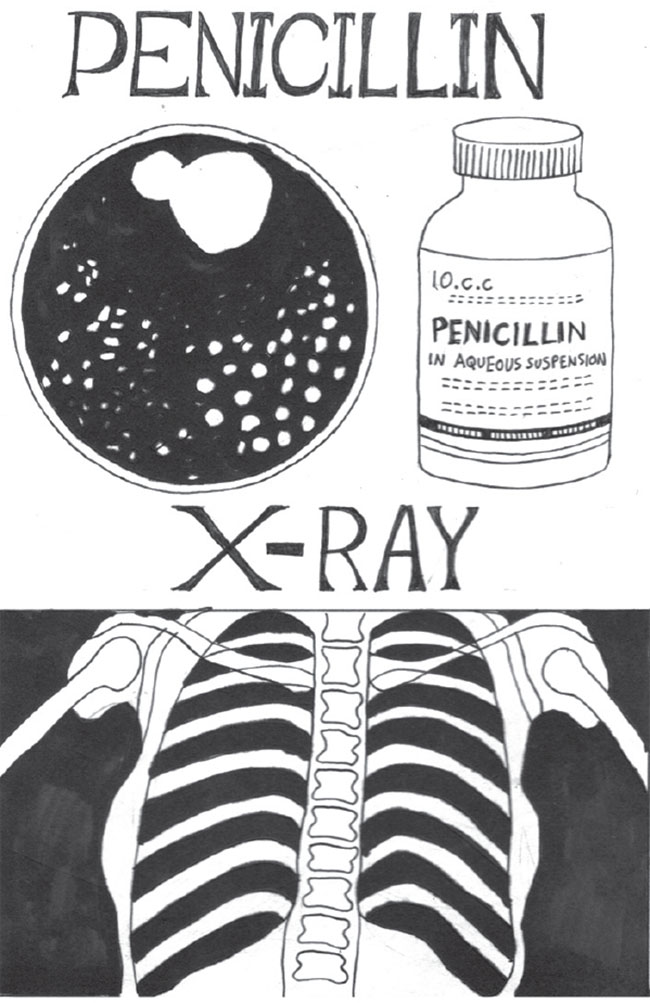

If enterprises are going to improvise, then it follows that there will be mistakes and occasional downright failures. How we respond to such things is therefore critical as leaders. The history of innovation is littered with mistakes and failures. We would not have penicillin without Fleming’s tardiness in leaving his culture plates unwashed while he went on holiday. Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays was thanks to careless handling of a photographic plate. I interviewed psychedelic rockers Hawkwind who were innovators of their age, performing with highly volatile VCS3 analogue synthesisers that would break down frequently or go out of tune due to the temperature. I asked them how they managed to reproduce their sound and the randomness with Apple Macs and they did admit that they had to consciously work at introducing failure into work in order to give it their characteristic strangeness and charm. The digital world is currently not as prone to analogue mistakes as the human condition and this makes it especially important for us to nurture our mistakes in the future if we are to produce things that take people by surprise.

When I worked in novel pharmaceutical development at The Wellcome Foundation we had an urgent and important problem on the pathway to the delivery of the world’s first HIV/AIDS product that came to be known as AZT/Zidovudine/Retrovir. We needed to make the very first products for clinical trial. The product was presented as capsules in blister packs. During the packaging process one in a million or so of the capsules would burst. You might think this is not a massive problem, yet a burst capsule in a production line would mean that hundreds and possibly thousands of capsules would have to be rejected due to powder contamination in the blister packing machine, which would mean that the machine would have to be completely cleaned and thousands of packs rejected due to poor sealing. Supplies of the drug were scarce and this obviously had massive implications for our ability to deliver this drug to patients in time and all efforts were directed to finding out the cause of the problem. All minds were applied to the problem and various ‘theories’ emerged. The most prevalent paradigm was that the machine was somehow damaging the capsules and a vulnerable one would break occasionally. High-speed video cameras were deployed and I recall spending hours looking for the source of the problem like a modern day Sherlock Holmes of drug development. All efforts were diverted to improving the handling of the capsules until I decided to study the gelatin capsules themselves, against the advice and hectoring of my bosses to “stay focused on the packaging machine and simply stake out the production department until I’d figured it out”. I did as I was told . . . and decided to do some other things . . .

p.167

p.168

I developed a set of elaborate experiments to test the capsules for rigidity and therefore potential fragility under stress during packaging. We had just introduced tamper-evident sealing of capsules due to concerns arising from the Johnson and Johnson Tylenol incident where people died from the introduction of poison into the capsules in 1982. Our tamper-evidence system required that each capsule would be filled with powder, the cap applied and then a liquid gelatin seal applied around the middle of the capsule. I hypothesised that this made the capsule much more rigid when shocked and may have contributed to the problem. I set about trying to replicate the ‘painting of hot gelatin’ on the capsules with an artists’ paintbrush. I started to notice that this did make capsules more rigid, but needed to find a way to test my hypothesis. Talking with my friend and colleague Jim Coghill, one day I ‘found the answer’. For some reason, unknown to anybody including me, I used to have a small bust of Lenin that I bought in Russia on my travels at that time. It sat staring menacingly at any bosses that wanted to speak with me in my office cubicle. I needed something to test my theory about rigidity and the bust of Lenin fitted the bill perfectly.

Jim and I started smashing capsule samples while discussing the rigidity/flexibility properties of ones that had the tamper-evident seal (banded) versus unbanded. Jim remembers picking Lenin up and smashing a capsule with him. V.I. Lenin burst this banded capsule, which resulted in a jet of toxic powder all over my desk. But Vladimir squashed the unbanded ones. On inspection, most of the powder was retained within the intact but deformed unbanded capsule shell. This was our ‘aha’ moment!

To create happy accidents we need both techniques/discipline and freedom from techniques/discipline. In this case, our ‘technique’ was not a spreadsheet or a machine but a found object, which allowed us to see the problem more clearly. True intelligence involves surrendering ourselves to the possibility that we will succeed if we open ourselves up to making a mistake in order to learn. This is especially so when you are stuck. Successful people allow space and time for free play/improvisation with the obstacles to progress. What I call ripening and incubation occur when we have mental and physical freedom to reflect and learn about obstacles to progress. This may be done in an active experimentation capacity, as our bust of Lenin shows. It may also take place in more passive contexts, such as the 3 B’s: in the bed, in the bath, in the bar. In our example of the capsule breakage problem, we felt we had the freedom to play and experiment with the bust of Lenin. This is how problems come to be solved, and not necessarily through sheer persistence.

p.169

As a result of these experiments, my attention switched locations to the department where the capsules were manufactured rather than the building where they were packaged. It turned out after much investigation that one of the process operatives would sometimes leave the gelatin roller running during lunchtime whereas others did not. On those occasions a small deposit of gelatin would build up on the rollers and one or two capsules would then get a marginally thicker seal as soon as production started in the afternoon. These capsules were the rigid ones that would be subsequently susceptible to breakage during packaging. All of our intelligence had prompted us to look in entirely the wrong places for the answer to the problem and it was counter-intuitive intelligence that eventually solved the problem.

The point here is that analytics and therefore machine learning/AI did not solve this problem. A machine would not have thought to smash the capsules with a bust of Lenin! We must embrace mistakes and failures if we are to learn faster than our competitors.

p.170

The power of dissonance

One thing I know, that I know nothing.

This is the source of my wisdom.

Socrates

People talk eloquently about the need to hire disruptors, but corporate life can all but squeeze the life out of those valuable free radicals of free enterprise. A good disruptor must be comfortable with and capable of managing what psychologists call ‘cognitive dissonance’. Turning to music to draw a simple parallel, musical dissonance occurs when two notes conflict together, due to them having frequencies that interfere. The effect is for the sound to somehow jar in your ear. In musical terms notes that are one, two or six intervals apart can cause the most interference effects that we experience as musical dissonance. In contrast, consonance is when those frequencies add together for a generally pleasant effect such as experienced in what are known as third part harmonies such as The Beatles, The Beach Boys and consonant four part harmonies in Barber Shop music. Listen to the beginning guitar phrase to ‘Paint It Black’ by the Rolling Stones just before the drums kick in to hear two dissonant notes, just one semitone apart. Speaking from the world of physics, the notes ‘interfere’ in a joyous way and give the song a distinctive motif. Other examples include Jon Lord’s keyboard solo on ‘Flight of the Rat’ from ‘Deep Purple in Rock’. The glorious clashing of guitars and viola on ‘Venus in Furs’ by the Velvet Underground is another good example. The best example of unbearable musical dissonance is Lou Reed’s classic album ‘Metal Machine Music’, which consists of 64 minutes of white and pink noise, which to most ears is quite unlistenable (and of course to a few is pure joy). Reed observed somewhat pompously on the album sleeve ‘My day beats your week’ in a rather carefree attitude to the record company who had wanted a repeat performance of ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ from his best-selling album ‘Transformer’. Heavy metal pioneers Black Sabbath are also masters of the universe in terms of using dissonance to great effect in their music, typified by the title track of their first album ‘Black Sabbath’, which uses the 6th interval as the signature motif. The 6th interval was considered so powerful that the Catholic Church tried to ban its use in the 16th century, long before our understanding of physics developed to the point that we understood that you cannot simply ‘ban’ electromagnetic radiation!

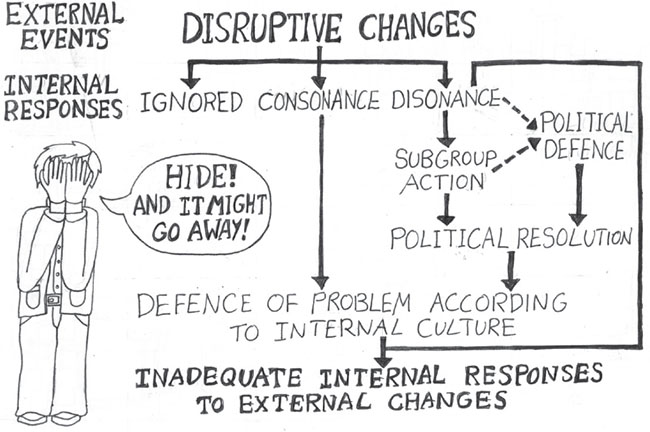

Yet many great earworms are the result of using unusual combinations of notes, which quite literally make the music unique. Dissonance can make musicians millions, so where is the useful parallel in psychology and business? Gerry Johnson offered us valuable insights about cognitive dissonance in his classic work on this topic. Businesses have a range of responses to disruptive external changes, ranging from ignorance, consonance or dissonance. Internal politics can kick in which usually results in conflict and then attack/defend spirals or referrals to committees. Worse still is denial. In all cases this leads to an inadequate response to external opportunities or threats with the consequence that the business fails to capitalise on external change. This might account for why Kodak did not see the Polaroid camera on the horizon, and why they failed to predict the impact of digital photography on sales of photographic paper.

p.171

p.172

A typical situation of cognitive dissonance in business is with ill-formed or dysfunctional teams at a meeting. Everyone says agreeable things. On leaving the meeting room everyone privately criticises the meeting, the views and even personalities of the people present. Unlike our musical example, cognitive dissonance can cost millions and even billions, as Pfizer found out with their inhalable insulin product Exubera. Leaders must get used to hearing ideas that do not accord or strike a chord with their own. The successful innovator is a master of gaining people’s attention to hear dissonant ideas and embrace them. There are different types of innovator:

• Conformist innovators accept the dominant values and relationships within the business and attempt to demonstrate how their activities contribute to the enterprise’s success criteria.

• Deviant innovators act by working toward organisational success in their own way, demonstrate that their contributions provide a different yet better set of criteria for change, thereby gaining acceptance of their ideas.

Elon Musk is a good example of a deviant innovator, having set up Tesla Motors in 2004, opening up all his patents and changing the dynamics of patent control by saying “We will not initiate patent lawsuits against anyone who, in good faith, wants to use our technology”. Tesla Motors also broke with tradition by selling direct to the public rather than via showrooms.

Greg Smith of Arthur D. Little sees the need to address cognitive dissonance as a business-critical issue when analytics do not match people’s mental models or beliefs.

We tend to hire young minds. The more senior some people get, the more people can become successful by what they know rather than their ability to find an answer. The more we define ourselves by knowing the answers, the more unsuitable we are in facing unknown and unknowable problems and challenges. A lot of seniority is based on knowing the answers rather than being able to find answers. The CEO should be the Chief Don’t Know Officer even though there are clearly times to be more knowledgeable such as when presenting to shareholders.

As consultants we are taught to deal in certainty and yet the best answers are often “I don’t know”. The dualities of one-zero, in-out, on-off are a limitation in finding ingenious solutions to problems as much innovation springs from the spaces in between these polarities.

p.173

GROUND CONTROL

Dissonance and consonance

Write down a number of your strongest held beliefs. These could be things about the world around you, your principles, expectations of others and so on.

Now reverse these beliefs in a radical way. Don’t just say “I don’t believe x”, think of a serious antithesis. For example, if you feel you get the best out of people by being nice to them, imagine that you believe that you get the best out of people by ignoring them or abusing them in some way.

Try ‘living with these beliefs’ for a few days and note how you feel about them over time. Ask questions of them from time to time.

Review your findings to see if you can extend the repertoire of your behaviours and beliefs as a result.