“If the rate of change on the outside exceeds the rate of change on the inside, the end is near.”

—Jack Welch

Truth be told, I didn’t realize it was a sales meeting until it was all over. We were in one of those non-descript-looking conference rooms—long table, Aeron chairs, and a lot of very serious-looking people, most of whom I didn’t know. They asked a lot of questions. Where were we based? How many people did we have? How would our platform operate on a large scale?

I looked around the room. They were nodding at each other, trading messages through thin air. But which way was the meeting going? Did they like what they saw? Were they going to throw me out and laugh about it afterward?

And then, suddenly, it was over. Thanks for coming in. Nice to meet you. Hope to see you again. After most of the people had filed out, the guy who had brought me in to present turned to me. This was the moment, I thought. The moment when he’s going to say no.

But instead he said, “How do you feel about doing a pilot? Can you send us a statement of work?” I breathed a small sigh of relief. Man, I thought, we might just make it. Because I wasn’t sitting in any conference room. I was sitting in a conference room at Walmart.com, the e-commerce arm of the world’s largest retailer.

Looking back over the past three years, the engagements that have been most successful for our clients have started with meetings not unlike the one we had that day. Granted, our slides have gotten a little more polished. We’ve built a comprehensive platform—the “Control Center for eCommerce ”—used by the biggest retailers and brands in the world. And we’ve grown in scale, analyzing more than 500 million products instead of the 5,000 for that first meeting at Walmart.com.

But our premise remains the same. Share compelling insight with our clients that they can’t get anywhere else. Find alignment on vision. Work together to deliver solutions that help our clients transition from in-store to online.

We call the organizations that are navigating this transition most successfully bricks-to-clicks companies. Typically, they are doing less than 20 percent of their sales online but want to do more.

The Bricks-to-Clicks Companies

Here’s what the bricks-to-clicks companies are doing well:

The bricks-to-clicks companies experiment obsessively. They don’t try just one approach. They try many different approaches in parallel. E-commerce is a world of experimentation.

The bricks-to-clicks companies adapt quickly. One supplier we work with theorized that sales from third-party sellers—marketplace sellers—might be eating into their growth. They immediately had us implement a new capability so they could measure the impact of marketplace sales on their first-party business. It turned out they were exactly right and now they have the data to prove it.

The bricks-to-clicks companies view growth in e-commerce as a long-term trend that is not going away. Just a few years ago when we were first talking to clients about Content Analytics, some told us that the time still wasn’t right for e-commerce—especially in areas like grocery—because there simply wasn’t enough money being spent on it to move the needle. Now we meet with directors and executives at these same companies whose jobs are dedicated to e-commerce. Many have built entire teams to address the specific needs of e-commerce .

The bricks-to-clicks companies apply technology so they can scale. Many of the clients we work with were trying to do brand audit s, brand content updates, and other activities manually, one product at a time. They’ve found that those processes simply don’t scale. What’s more, they consume an enormous amount of time of the personnel tasked with marketing, merchandising, and sales. They’ve brought in technology to help them scale up and to free their valuable people to do the jobs they came to do.

The bricks-to-clicks companies reduce their cycle times so they can operate at Internet speed. One supplier we work with told us they were used to getting a static brand audit once per year. Another supplier told us they were used to updating the content that showcases their products on retailer web sites once per year. Since they began working with us, both of these clients have used technology to accelerate their cycle times and are now able to receive brand audits, out-of-stock reports, and pricing reports and update their content on a daily basis.

The bricks-to-clicks companies use e-commerce to reinvent their workflows, processes, platforms, and organizations. They see that a decade from now, e-commerce will have transformed not only the online shopping experience but the in-store shopping experience as well.

Partnering with the World’s Largest Company

That is only half the story. The other half of the story—the theme that has emerged from three years of working with Walmart, P&G, Clorox, Levi’s, Mattel, Samsung, and many other of the world’s leading brands—is that thought leaders at bricks-to-clicks companies not only have the vision required to see the future of e-commerce but also have the interest and ability to build consensus across their organizations that organizational transformation is required to compete in that future e-commerce world.

It is one thing for an individual to take an interest in our product and what it can do to help our clients operate in the world of e-commerce. It is another thing altogether for a group of individuals within an organization to agree to bring us and our platform in to help them drive that transformation, not just internally but across all their suppliers as well.

That brings me back to that pivotal meeting at Walmart. As I walked out of the building that day, I realized two things. First, we were about to have the world’s largest retailer as our first paying customer. Second, we had better get to work building out our software platform to support immense scale. Providing insights for 5,000 products was one thing. Doing so for 5 million of them—and pretty soon 50 million of them—was going to be a much bigger, bet-the-company kind of challenge.

At the time, I was too excited to understand the implications of the meeting. But looking back I can see that Walmart did an amazing thing that day. They partnered with an early-stage company to accelerate getting the insights they needed. They did something that is difficult for even the nimblest of companies—they took a risk.

These days, now that we have a number of market-leading customers, things are different. But back then, partnering with us as an early-stage startup was no small feat. As the old saying goes, “No one ever got fired for buying from IBM.” Partnering with us meant getting us onboarded as a vendor, carving out time to meet with us on a regular basis, and convincing company leadership that we could deliver value not found anywhere else.

Over the years, people have asked me if it’s hard selling to large companies. The answer is that it’s not hard as long as we truly view our internal sponsors as partners.

Many startup founders come out of meetings with potential corporate sponsors wondering why their sponsors are so tough on them. They’re so tough because the questions they’re asking us are the same questions their peers, leadership teams, and procurement teams are going to ask them. Better that our sponsors ask us the tough questions early in the process so we can be prepared for them when they arise rather than waiting until someone else asks them and takes us out of contention later. A big part of our job is to build innovative technology that will help our customers beat their competition. But an even bigger part of our job is to help our customers bring those new capabilities into their organizations.

The next nine months were some of the toughest I’ve ever faced as a startup founder. First, we had to get through procurement at Walmart—that was the easy part. Second, we had to make our analytics platform work for millions of products, day in, day out. Third, we had to present all the data we were gathering in an easy-to-use and compelling way. That turned out to be the biggest challenge of all.

I met with people from Walmart almost every week. I made it a point to go in person because the best feedback came from these weekly conversations. Over the years, I have continued to meet with customers to get product feedback like this in person. Simply put, there is nothing like it.

As a buyer, any startup you work with will value the money you pay them. Money from customers is the best form of financing. After all, it doesn’t require a startup founder to give up any equity. And there’s nothing like a paying customer to help convince investors to invest! But equally valuable is the time that you as a buyer invest with a startup you’ve partnered with to provide input on product direction.

In customer meetings, I’m constantly taking notes on my smartphone, so much so that one of our customers once said, “If Dave writes it in his phone, it’s going to make it into the product in just a few weeks.” These days of course I’m careful to tell customers that I’m not busy doing e-mail or texting—I’m writing down their product feedback so I can get it back to our product team!

During the nine months of getting our platform to scale, we had some incredibly stressful weeks. For whatever reason, I got in the habit of wearing white dress shirts to my Walmart meetings. Our team always knew when I was going over to see Walmart before I told them. They could tell by the white dress shirt. Even our customers at Walmart found it amusing. One of them jokingly asked me if I owned any other dress shirts. I had to admit that my closet was full of white dress shirts!

The biggest challenge was preparing for the weekly meetings. To be ready for the meetings, we had to collect, analyze, and display the product data. Again, that’s not so hard to do for 5,000 products. But it was harder than we thought to do for millions and millions of products. Sometimes we’d get stuck in the data collection stage, other times in the analysis stage. A lot of the issues we faced stemmed from trying to move large amounts of data from one location to another. It turned out that a seemingly simple process took a lot longer than expected, until we made a key technical breakthrough that allowed us to leave all the data where it was and not move it around. From there on out, we were in good shape.

But just when we thought we had done everything we needed to do, we came across an even bigger challenge: how to communicate the insights we were generating in a form that the buyers, merchants, and merchant assistants at Walmart could act on.

Note

When it comes to analytics, gathering the data is a challenge. But delivering insights in a way that business users can act on—that’s an even bigger challenge.

Showing these users row after row of output data simply wasn’t going to cut it. Instead, we needed to summarize the results in a compelling visual fashion. Only after that should we deliver the detailed action items.

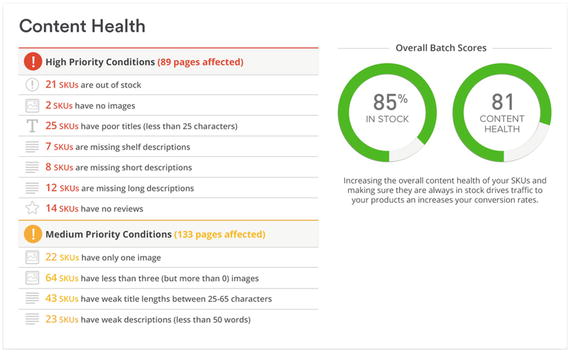

It was from that need that our Content Health audits, now the standard in the industry, were born (Figure 1-1). Content Health audits show our users, at a glance, how they’re doing and where their biggest opportunities are for improvement.

Figure 1-1. Content Analytics Content Health audit

Expanding Our Reach

A company like Walmart is so large that frequently people from different groups or divisions rarely have a chance to interact with each other in person. Speaking of himself and his colleague, another vice president, a vice president at Walmart once told me, “Dave, we don’t meet up nearly as much as we should. You’re giving us a rare opportunity to get together and share ideas.” Put another way, the adoption and expansion within the organization of a new technology platform—especially one that is used for high-level key performance indicator (KPI) reporting—can be a key mechanism for individuals and even entire groups within large companies to collaborate.

In the case of Walmart, our product brings together colleagues from marketing, merchandising, buying, and technology development. For a long time, I thought the main purpose and benefit of expanding our reach within another company was so that we could drive more revenue. Only more recently did I come to understand that there is a larger benefit to the “land and expand” strategy.

The more the usage of a product expands within a company, the more valuable that product becomes to the company using it—not just to the company selling it. There is an efficiency of scale that occurs when large companies use a platform throughout their organization. Looked at another way, adopting a technology platform is a form of building consensus. Regardless of the individual value any one user derives from the platform, the organization as a whole has determined there is sufficient common value to adopt the platform across multiple groups. This is how internal expansion works within a company.

External expansion can be equally as important. In the fall of 2014, after we had raised our Series A round of financing, I drove up to Napa from our office in the SoMa district of San Francisco to see one of our angel investors, Joe Schoendorf. Joe had been a very successful partner for many years at venture capital firm Accel Partners (famous for putting early money into Facebook), and his wife Nancy Schoendorf had been a partner and managing director at Mohr Davidow Ventures with many successful investments herself. That day I had a specific topic I wanted to discuss with Joe and Nancy: how we could expand our target market.

In the heat of being excited about the insights our technology platform could bring to a retailer like Walmart, we had discovered (as should perhaps have been obvious earlier in the process) that the market for selling software to retailers was not that big. In fact, many of them seemed to be fast going out of business, with constant reminders of the ineffectiveness of their legacy brick-and-mortar model in the form of headline-catching store closings numbering in the hundreds per retailer. Macy’s, Kohl’s, JCPenney—none was immune from the pressure of e-commerce.

Before his career as a venture capitalist, Joe had long before been a brand manager. As I told him about all the insights our analytics platform could provide, from out-of-stock to pricing data and from marketing metrics to competitive insight, Joe came to an interesting conclusion. Our biggest market, he observed, was not the retailers themselves but the hundreds of thousands of suppliers that made up their ecosystem. The Procter & Gambles, the Cloroxes, the Levi’s—there were far more of those companies than there were big retailers. What we were building, Joe observed, was not just an analytics platform but a complete brand management platform for e-commerce. We were providing the kind of insight brand managers had always wanted but found so difficult to get their hands on because of the challenges of gathering in-store shopping data.

But the Web was different. With the Web, instead of having to send tens of thousands of people into stores to gather pricing, inventory, and placement information, we could automate all that data collection with software. Not only that, but we could do it quickly, reliably, and at immense scale.

From there was born the idea for the end-to-end platform that our product has become: the “Control Center for eCommerce .” We would offer analytics, content management, and reporting with a road map for capabilities such as listings management and dynamic pricing down the line.

Note

Content Analytics provides an end-to-end platform for analytics, content management, and reporting in e-commerce.

I left our lunch realizing we had two markets to go after—retailers and suppliers. The more retailers we secured as customers, the more suppliers we would get, and the more suppliers we got as customers, the more likely it was that any given retailer would want to work with us. As I headed back to San Francisco, I felt invigorated. It would turn out that as big an opportunity as selling to retailers was, expanding to suppliers was even bigger.

Our product lent itself particularly well to this kind of external expansion. That’s because our Content Health reporting system identifies opportunities where suppliers can improve their online product presence.

As a result, buyers at retailers are inclined to share the Content Health reports with their suppliers so their suppliers know where they need to improve. On the one hand, we can provide sitewide analytics to our retail customers; on the other hand, we can drill down to a specific supplier and provide insight into how that supplier is doing relative to its peers and which specific items can be improved and how.

At our supplier customers, “land and expand” works in much the same way. We often start with just a few users—from shopper marketing, sales, supply chain, or e-commerce management. In some cases, our supplier users come from retailer-specific teams within their companies. These teams sell to and support their retail partners such as Amazon, Walmart, Jet, Target, and others. In other cases, our users have a more global function, managing e-commerce across two, three, or even as many as ten, twenty, or more retail partners.

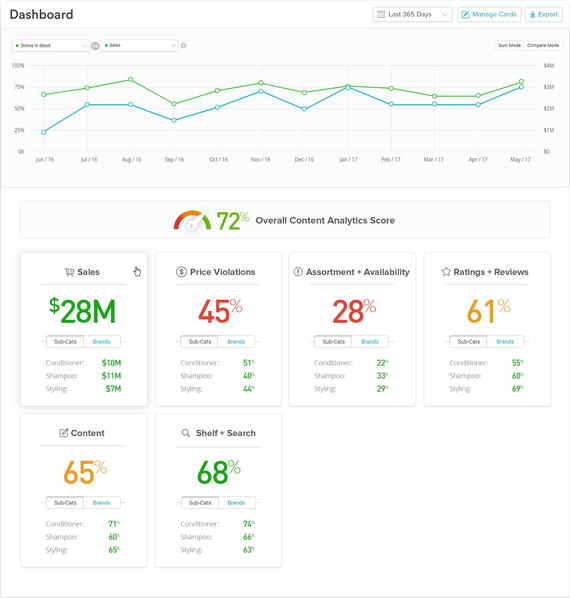

Sometimes we’ll solve a specific point problem, such as an issue with out-of-stock items. Other times, we’ll provide a comprehensive business Dashboard (shown in Figure 1-2) that covers all of a company’s e-commerce metrics and allows users to drill down in specific areas, such as pricing or content health .

Figure 1-2. The Dashboard

If we start with the broad Dashboard, we often find ourselves expanding to users who focus on specific functional areas, such as supply chain management. If we start out solving a specific issue, we later find customers asking us if we can help them solve other challenges, such as measuring price volatility or content health . Either case means an expansion—a growing consensus within the supplier that even though the benefit from our product to any one individual may be different, there is agreement that there is overall benefit to the customer across multiple users (and therefore across multiple groups).

This kind of cross-group adoption of our product (and any technology product, for that matter) is crucially important both for the company making the product and for the company using it. It means there is consensus on creating change within the organization.

Of course, there are many retailers that our suppliers sell through but don’t have time to interact with regularly on a one-on-one basis. In fact, specialty independent retailers (SIRs) are the fastest-growing segment of the retailer part of e-commerce.

Suppliers like Levi’s want not just to report on their performance across these retailers but also to improve the way their brands are represented across these retailers. They want to ensure that these retailers are showing the current images, product descriptions, and videos possible. Yet at the same time, they don’t have the resources necessary to deliver updated content to every single one of these retailers.

Once again, technology to the rescue. In this case, our suppliers introduce us to their retailer partners, to whom we can then deliver comprehensive, up-to-date content directly from the suppliers, further increasing the network effect. Our Master Catalog is a comprehensive, cloud-based product information management (PIM) system that stores brand content and delivers that content to retailers in the form they expect. Not only do our supplier clients build consensus and drive change internally, but they also drive change externally. No matter which side of the table you’re on, the model is a powerful one.

But what about when the use of products does not expand internally (and externally, when it makes sense)? In that case, customers need to evaluate two possible causes. First, there is the possibility that the product in question is simply not a good product. Users find it difficult to use or it isn’t delivering on the functionality it promised. Second, lack of usage expansion can be a signal that the company has failed to reach consensus that change is needed or that the right stakeholders weren’t involved early enough in the purchase process. In such cases, the product often needs to be re-bought, with the right stakeholders involved from the get-go.

Reducing Risk in Technology Adoption

One way some customers have reduced the risk associated with adopting a new technology platform like ours is to run low-cost pilots to try us out. Procter & Gamble (P&G), for example, first evaluated our product during a three-month pilot focused on reducing out-of-stock rates. Although our product was still relatively early in its development, our sponsor had the vision to see its potential. During the pilot, not only did P&G’s in-stock rates improve, we were also able to deliver increased visibility to help them identify the possible sources of issues causing products to go out of stock.

Although some prospects ask us to do free pilots, paid pilots nearly always produce better results. That’s because clients take paid pilots more seriously than free pilots. On our end, it means we know a client is serious about doing business with us, assuming things go well during the pilot. A paid pilot also helps with prioritization—anything paid is going to get a higher priority than something that’s free. Paid means that both sides have made a commitment to the pilot. The customer is paying and expects value in return; we’re getting paid and expect to deliver on that value.

Paid pilots are also a great consensus-building mechanism for our clients. In most larger organizations, paying for something means that at least a few other people have to get involved, whether that’s a manager, a vice president, or a team.

Of course, many clients choose to skip the pilot altogether and go directly to a purchase. The way our platform works, it’s possible for us to load actual client product information and analytics into our platform with no integration on the client’s part. In fact, this was one of my underlying requirements for the platform—that we be able to go into initial client meetings with data preloaded.

At a previous company that I started, I had experienced the pain involved for both us and the customer when we had to perform months of integration work up front before we could deliver any value. I vowed at Content Analytics that we would put neither our customers nor ourselves through that kind of pain. This in and of itself is another form of risk reduction: enabling customers to get value from a new technology in a matter of days or even hours rather than months or years.

Note

One of the key innovations in our platform approach is that we can be up and running in a matter of days—rather than in months or years.

This innovation, the ability to get up and running and deliver immediate value, turned out to be one of the key selling points of our platform when we went in to pitch to a major apparel maker.

Ironically, we were late to the party. In the summer of 2015, I had been asked to be the keynote speaker at an e-commerce event in San Francisco. One of the attendees at that event, a business development executive for a major consulting firm, came up to me afterward and suggested that we partner, specifically in the area of e-commerce. It made complete sense. We would supply the technology platform, and the consulting partner would supply the services and ongoing project management.

Just a few days later, our contact told me he had a great opportunity for us with a local apparel retailer (one of the world’s largest). A director at the company was looking for a way to report on key e-commerce metrics. He was relatively far down the path in the vendor selection process but was interested in seeing what we could provide. We would be talking with him the next morning. With little time to prepare, we pulled together a set of slides and a demo with a comprehensive analysis of the company’s products.

When I later asked the director what had caused him to choose our solution over the competition, he told me point blank that it was the speed with which we could deliver value. They’d been working on the integration required for a competitor’s solution for almost a year. In contrast, we were able to deliver value on a day’s notice. If there’s one thing that reduces risk even more than a pilot, it’s seeing insights about your own products live in our platform during a first meeting.

Customer-Driven Development Model

When it comes to making a purchase decision that has the potential to transform the way your organization operates, it’s important to ask yourself what kind of buyer you are. Some of our buyers are pioneers—they see the future of e-commerce and want to bring in the necessary technology to support it. Others are entrepreneurs within large corporations—they simply want to contribute some of their hard-won knowledge to help a startup grow. And still others are proven operators, trying to solve a set of problems they’ve had for a long time—tracking down missing inventory or storing brand content that’s located in a million different places in a centralized location.

None of our customers fits one profile alone. Many want to be involved in some way with a startup while getting the capabilities they need to solve their immediate business needs. All understand the requirement to build consensus within their organizations. They see our platform as a centralized control center that will truly help them improve their business operations. And they’re not shy about telling us what they think should be on our product road map and when.

So much of what we do involves listening to our customers’ explanations of how their businesses operate—and how they could operate more efficiently—and then building the software that makes more efficient operation possible. I often feel when we have a successful client engagement that our software platform is the last thing we sell. What customers really buy is our ability to understand their needs, translate those into execution, and solve their problems quickly. We happen to sell them a license to some software so we can get paid. But what they buy is an entire operating model that helps them solve their business challenges.

This kind of customer-driven development (CDD) model requires an immense investment of time and effort on our part with our customers. But without it we would not have the kind of comprehensive “Control Center for eCommerce ” that we have today. Of course, it’s a two-way street. When we come up with a new idea for a product capability or spot a new trend in the industry, our existing customers are the first to hear about it.

Operating at Web Speed

Quite often, our customers know they want to change the speed at which they operate, but their biggest challenge is: how? When I asked one of our sponsors at P&G how often he was used to getting certain reports about the health of his brand, he showed me a PDF report file that had been put together by hand. “We get this once a year,” he said. He wanted to get an updated version of the report every single day.

Many of our clients have become the captains of their categories (that is, the number-one player in their category) through decades of investment of capital and human resources in the offline world. Their brands are known the world over. The strategy worked because in the brick-and-mortar world, it was the ability to buy out the shelf and apply capital and human resources to building brand value that mattered most. Speed was simply not the number-one factor that determined a brand’s success, and the systems that allowed brands to operate internally and to connect brands with their retail partners demonstrated as much.

In the e-commerce world, speed is everything. Millions of new products become available for sale online every day. The digital shelf changes from minute to minute.

Companies can and are taking immediate action to boost share of voice, increase product visibility, and respond to changes in product availability. The days of waiting until the end of the quarter or the end of the year to make a change are over. In e-commerce, every second counts.

While we’re not the only company that can help our clients operate at web speed, our customers have told us that we are one of the few. For us to help our customers operate at web speed, we have to operate at web speed ourselves. To do that, we rely on a certain set of web operating principles.

Deliver new product capabilities in weeks, rather than in the typical enterprise cycle of quarters or years.

Deliver data insights and brand updates in seconds, minutes, or hours, rather than in weeks, months, or years.

Operate at unparalleled scale, providing insight and brand management capabilities equally effectively across billions of items as we do across hundreds of items.

Use a modern, cloud-based technology stack that supports scaling up compute resources on demand.

Combine many sources of data into one comprehensive view, rather than operating as another silo within organizations that are already heavily siloed.

Meet the needs of our individual users while delivering a platform that provides value across our clients’ entire organizations.

Use a customer-driven design approach so we build real, practical solutions, rather than spending months in the back room building software that no one will ever use.

These principles that make up the core of our organization are the very same principles we bring to the companies we work with.

In many cases, our clients have had new ideas about how their businesses should operate for years—they simply haven’t been able to find a partner to work with that can deliver on those ideas. To every partnership, our clients bring their domain knowledge and expertise; we bring our proven technology execution capability. In our minds, it is an unparalleled focus on the CDD model and a proven ability to execute that our clients should be looking for when choosing a technology partner. If one thing holds true in the web era of commerce, it is that new capabilities are constantly emerging. As a result, it’s not enough for buyers to partner with technology vendors who can solve the needs of today. They must partner with buyers who can solve the needs of today and rapidly iterate to solve the needs of tomorrow.

Stop the Meeting

Early on in our work with a director and his team at one supplier, we were reporting on average review rating and review counts. The director knew his company had an issue with reviews on a particular retailer but hadn’t been able to pinpoint the exact issue. What our reports showed was that only a certain segment of the supplier’s product assortment had an issue. This segment of the assortment not only had a limited number of reviews but also had low ratings—few reviews with low ratings is not a good combination.

We had one of those moments I love to talk about—our customer exclaimed, “Stop the meeting! I know what to do!” He immediately contacted the team at his company responsible for reviews. That team updated the company’s review syndication approach. Almost immediately, the supplier started receiving a more representative mix of reviews and a larger quantity of reviews.

What was happening? The supplier has both a direct retail site (that is, a site where they sell direct to consumers) and a thriving wholesale business. For this part of the supplier’s assortment, shoppers were writing large numbers of reviews and almost all of them positive reviews at that. But most of those reviews were being sent to the retailer’s retail site. The small number of remaining negative reviews were being syndicated via the supplier’s review syndication network, producing an artificially negative perspective on an otherwise great product.

At Content Analytics, we live for these “stop the meeting” moments when we deliver an insight so valuable to a supplier or retailer that they’re able to take immediate action. This is just one small example of how we partner with our clients to help them transform their businesses.

Summary

People often ask me why I started Content Analytics. My first response is normally that I was looking for an opportunity at the intersection of Big Data and a rapidly growing market. In building and delivering the world’s foremost “Control Center for eCommerce ,” I have found that intersection.

Yet it is the intersection of our software platform with our customers’ business needs that has proven even more rewarding. In building Content Analytics, I’ve had the privilege of getting to know and work with leaders inside some of the world’s most innovative brands—both large and small. That interaction has enabled us to build software that solves real, pressing business challenges.

One of the biggest challenges facing brands today, of course, is an increasing loss of control. Consumers are taking comparison shopping to a new level from the convenience of their mobile phones, while computer algorithms are exerting ever more control over the digital shelf. How can brands regain control? We’ll take a look at the answer to that question in the next chapter.