“Content Analytics gives us the tools to make sure we’re not just watching, but instead are leading the charge.”

—Mattel

Supplier Case Study

In 2016, using the Content Analytics platform, bricks-to-clicks supplier Mattel had their single best year ever on Walmart.com. They increased their shipments to Walmart.com 39 percent over the previous year. That was more than five times better than the industry average of 7 percent predicted by research firm NPD. As Mattel put it, “We’ve never seen numbers like this before.”

Mattel is one of the world’s largest toy makers, with nearly $6 billion in annual revenue.

Rewind just a few months. Mattel saw a tremendous opportunity. They could see that e-commerce was growing. And they knew that a successful omnichannel activation approach would need to be at the center of their go-forward strategy.

Note

By using the Content Analytics platform, Mattel achieved more than five times better sales performance than the industry average.

At the same time, Mattel was faced with tremendous complexity. They were selling thousands of items across multiple channels. They needed a way to track and improve pricing, out-of-stock rates, and online product presence. They needed a complete solution that would give them end-to-end control. They found it in the Content Analytics platform, which fit seamlessly with the company’s focus on best-in-class omnichannel management. Mattel realized immediate success for a number of their original objectives.

Improving content health

Improving out-of-stock rates

Owning the Buy Box

Here’s how they did it—and how you can too, whether you’re just getting started in e-commerce or already have hundreds or even thousands of items for sale online.

Improving Content Health

Mattel’s first step with their new set of e-commerce tools was to go after what they identified early as a key obstacle: content quality. Improving the quality of their content would provide a significant impact quickly, leading to more sales. They used Content Health reports to identify products where they needed to optimize titles and product descriptions, add search-optimized keywords, and add or improve photos and videos. They leveraged the editing capability built in to the Content Analytics platform to make the content updates. Based on this work, they steadily improved until they achieved perfect content health scores, which they continue to monitor and maintain.

Content Analytics Content Health reports have become the standard in the industry because of their highly actionable nature. They provide you with the exact information you need to improve the content quality of your item pages.

Improving Out-of-Stock Rates

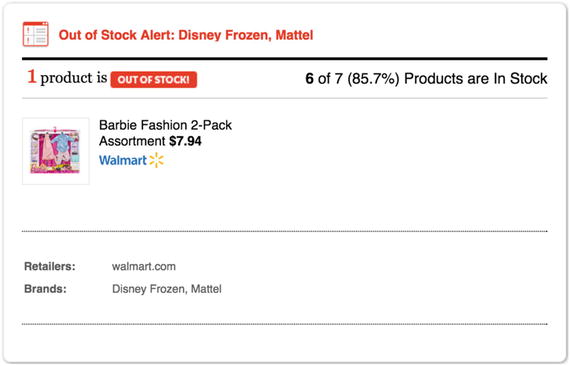

Mattel’s second step was to reduce out-of-stock rates. Mattel used a combination of out-of-stock reports and alerts to identify out-of-stock issues and take action when they occurred. Using the reports and alerts, they were able to reduce their reaction time by five days. As a result, they improved their out-of-stock rates for the Mattel Girl’s assortment from 43.7 percent to 16.3 percent.

Figure 4-1 shows a sample Out of Stock alert.

Figure 4-1. Out of Stock alert

As with other alerts, you can configure Out of Stock alerts to be sent just to yourself or to multiple people within your organization. That way everyone responsible for addressing supply chain and inventory issues can get notified at the same time.

Owning the Buy Box

Mattel’s third step was to make sure they were owning the Buy Box as often as possible. On Amazon.com and Walmart.com, when a seller wins the Buy Box, that seller becomes the default seller that captures the sale when a shopper adds the item to their shopping cart . If a seller prices an item higher than other sellers or is out of stock on an item, that seller will lose the Buy Box. First-party suppliers are constantly competing to win the Buy Box with marketplace sellers who sell the same item. So when a Mattel item went out of stock, a third-party (marketplace) seller would win the Buy Box. The result was overpriced purchases (which Mattel did not capture the additional revenue from) or abandoned sales. This loss of control was destroying value for both the retailer and Mattel.

Mattel used the Content Analytics pricing tools to receive notifications when prices went too high. They were able to notify their retail buyer who would adjust the prices back down to maintain ownership of the Buy Box, resulting in more direct sales for the retailer and Mattel .

Whenever the Buy Box went to a third-party seller, Mattel received an alert from the Content Analytics system. From these alerts, Mattel stumbled on a breakthrough. They decided to set up Mattel as a marketplace seller so they could be a third-party seller themselves for the same items in the Walmart.com marketplace. Thus, the “Mattel Shop” was born, demonstrating Mattel’s innovative approach as a bricks-to-clicks supplier.

When a Mattel item was out of stock on Walmart.com (direct), the Mattel Shop kicked in as a third-party seller to secure the Buy Box. This preserved brand equity, maintained control over the customer experience, and captured the customer as a Walmart-sourced transaction. What’s more, in the first month of operating the Mattel Shop as a marketplace seller, Mattel captured an additional $1.6 million in sales.

Mattel was careful to leave the Mattel Shop pricing just above Walmart.com’s own direct pricing. That way, Mattel never took the Buy Box away from the retailer and there was no cannibalization of direct sales.

Futures

Mattel has established four clear goals for their go-to market efforts.

Achieve long-term omnichannel success

Improve reporting and the supply chain to support omnichannel integration

Integrate processes to improve channel management and communication

Optimize the mobile shopping experience for research and conversion

Among the traditional bricks suppliers and retailers we work with, omnichannel is one of their top priorities. It has to be. For the first time ever, according to a joint UPS and Comscore study, shoppers are doing more of their shopping online than in stores, with more than 50 percent of purchases now made online.1 When it comes to the next generation of shoppers, millennials, the percent purchasing online is even higher, with millennials now making 54 percent of their purchases online. Online purchasing is here to stay, and suppliers and retailers alike are eager to get it right.

A study of 46,000 shoppers shows that omnichannel merchandising does work. Omnichannel shoppers spend more than their single-channel counterparts, with omnichannel participants in the study spending 4 percent in stores and 10 percent online.2 Omnichannel shoppers are also more loyal, logging “23 percent more repeat shopping trips” within six months after an omnichannel shopping experience.

Even historically online-only retailer Amazon.com is getting in on the act with the introduction of Amazon Go stores. Amazon Go is Amazon’s next-generation in-store shopping experience—with no checkout process. What makes Amazon Go different than most (all?) stores is that the store automatically figures out which items a consumer has taken from the shelf.3 The technology to track consumer behavior in stores (such as identifying specific walking paths through the store) has been around for some time. But this is the first an association is being made between an individual consumer action (taking an item off the shelf) and an item. Typically consumer actions are aggregated into more general models that are used to improve store and shelf layouts.

While the first-ever Amazon Go store (which so far is available only to Amazon employees) shows a promising picture of the store of the future, many suppliers and retailers are concerned with the here and now of today’s omnichannel experience.

The retailer ultimately controls the physical store experience. Yet suppliers have a great deal of control over the digital experience that accompanies that in-store experience, as well as the reporting that goes with the omnichannel experience.

Often when people talk about omnichannel, they mean the combination of in-store and online. But with always-connected mobile devices and an increasing propensity toward shopping on those devices, mobile should be considered an important channel in its own right in the omnichannel equation. Purchasing on smartphones continues to increase year over year, and some 63 percent of millennials now make purchases on their mobile devices. Now that bricks-to-clicks suppliers like Mattel have succeeded in achieving many of their core e-commerce optimization goals, their next step will be to optimize their omnichannel experience, across in-store, desktop, and mobile.

Retailer Case Study

Switching gears to the retailer side of the house, inventory optimization is one of the most frequent challenges we help with—and one of the most common issues we find. One retailer we work with had an ongoing issue around missing inventory. This isn’t inventory that was lost or stolen; it was inventory that their inventory feed said was there, but then that inventory mysteriously did not appear on their web site. What was going on? Where was the missing inventory?

In contrast to out-of-stock reporting, when we talk about inventory, we’re typically referring to a data feed or inventory status file we’re receiving directly from a retailer or supplier’s inventory management system. (In the supplier’s case, this normally applies to cases where the supplier is fulfilling the product directly, such as drop-ship vendors or marketplace sellers.) Inventory data usually comes from a back-end inventory management system that tracks how many units of inventory are on hand for every item.

On the surface, it seems like inventory feed data and the in-stock/out-of-stock status as reported on a retailer’s web site should be identical. Yet suppliers and retailers know all too well that this is often not the case.

I’ve gone into more than one prospect meeting thinking this is the one. This is the meeting where they’re going to tell me that they simply don’t need out-of-stock reporting—that they’ve got it covered. But I’ve never had that meeting. More often than not, I’ll go into a prospect meeting armed with a fresh out-of-stock report (the true shopper view of things) only to hear someone exclaim, “Wait, I thought those products were in stock!”

A complex combination of retailer system settings, physical product sources, and time-of-day issues determine whether products are shown as in stock or out of stock on a retailer’s web site.

To help solve the problem, the first thing we did was set up a daily inventory data feed from the retailer’s inventory system (in their case, GSI Commerce) to us. There was no complex integration—simply a data dump to us from their inventory system. We then started crawling the same items on their site. From there we could immediately tell there was a big difference between what their inventory system was reporting was available and what their web site was showing shoppers was available for purchase.

More importantly, we could tell exactly which products were being reported differently in the inventory system compared with what was displayed on the retailer’s web site. Previously, the retailer only knew that they had a big problem: there was a large quantity of inventory mysteriously missing, but they couldn’t tell which products were the issue.

Armed with the information about which specific products were different between the inventory system and the web site, the retailer has been able to track down the missing items. In all, we’ve helped the retailer find more than 60,000 units of inventory per month that should have been for sale on their web site but weren’t—millions of dollars in inventory that otherwise would not have been for sale. In the process, we’ve also helped the retailer improve overall customer satisfaction because there’s nothing more frustrating for a customer to find the item page for a product they want to buy only to discover that it’s out of stock. Or perhaps it’s more frustrating for a retailer to have the product a shopper wants to buy on hand and not be able to sell it to them.

As you can see, this intersection between retailer or supplier-provided data and web-crawled data is a powerful one. When we bring together multiple sources of data in this way, we can create meaningful new insights for our clients that weren’t available from the data when it was delivered separately—if it was delivered at all.

Leadership Opportunities

For many suppliers and retailers, e-commerce simply wasn’t a big enough channel to invest in—until suddenly it was. As a result, many bricks retailers and suppliers waited too long to stake out leadership positions in the e-commerce space. Yet there are still many opportunities.

Here’s how a few of our supplier clients are taking leadership positions in their respective verticals:

Electronics

Multiple dedicated e-commerce headcount

Comprehensive business reporting dashboard

Minimum advertised price (MAP) reporting

CPG

E-commerce centers of excellence

In-stock optimization

Robust cross-retailer pricing analytics

Brand integrity monitoring

Comprehensive content optimization

Apparel

Reporting across all major retailer e-commerce channels

Automated brand integrity checking, including for descriptions, imagery, and videos

Streamlined multiretailer content updating

Optimizing for scale

Home

Imagery improvement (more images and higher-resolution images)

Streamlined item setup process

Steps to E-commerce Leadership

Based on our work, we’ve identified four key steps to establishing leadership in e-commerce.

Be present online.

Use metrics to drive rapid, continuous improvement cycles.

Adopt a minimum viable product (MVP) approach.

Embrace the new path to purchase.

Be Present Online

The first step—being present online—may seem simple and obvious, yet many prospects we talk with are still establishing their presence online. When we analyzed the item pages of one large processed food maker on a few of their main retailers, we found that their items were for sale online. That was seemingly good news, except that the food maker was not a direct seller of any of their items. As a result, third parties (marketplace sellers) were listing the company’s items for sale on Amazon and Walmart. The company had no control over their brand/product presence.

Their products were being sold at all kinds of different prices, completely unrelated to what a shopper would expect to pay for the same items in a store. The imagery that most of the marketplace sellers used was poor—low-resolution images that did not do justice to the products and were often of lower quality than the images on the supplier’s own brand site. Plus, the supplier’s products were not optimized for maximum visibility in search on the retailers’ web sites.

When we first talked with this supplier, we realized that they were not yet at the optimization stage. They were at the initialization stage—getting their products online. To get products online, bricks-to-clicks suppliers follow a few key steps.

Identify the products they want to get online.

Set up those items.

Create best-in-class content for those items.

To help new suppliers get started, we often show them examples of the following: content health audits for best-in-class e-commerce suppliers, fully optimized item pages containing great content, and fully built out e-commerce reporting Dashboard s. This quickly gives new suppliers a sense of what winning will look like.

Of course, being present doesn’t end with having items for sale on retailer web sites. It’s also important to have a great brand site, filled with compelling content. That means putting high-resolution images, optimized product descriptions, and videos not just on your retailer partners’ web sites but on your own brand site. Fortunately, the Content Analytics platform not only can provide reports and recommendations for your retailer product presence but can do so for your brand site (if you have one) too. Once you are set up as a direct supplier to your e-commerce retail channels and you have a fully built-out brand site, you’re in a much better position to control—or at least influence—your brand presence online.

Use Metrics to Drive Rapid, Continuous Improvement Cycles

Many of our suppliers use the reporting metrics we provide to drive improvement at the individual, department, company, and partner levels. Metrics are typically used to motivate behavior.

Internal measurement: Heatmaps enable you to compare performance across departments and brands within your company, helping you to manage and optimize your entire portfolio. Cross-retailer heatmaps let you see where you have opportunities to improve across retailers, which is especially useful when you have sales teams that sell to specific retailers.

External measurement: Suppliers use the Content Analytics Competitive Insights module to evaluate external competition. This module supports brand groups. Each group can have a primary brand—your brand and the competitor brands. Bricks-to-clicks clients who are managing a portfolio set up multiple brand groups so they can check on each brand.

Time-based measurement: Suppliers use time-based competition, with both internal and external metrics, to motivate performance. Suppliers want to make sure their products continue to perform well over time—and they ideally want to see metrics continue to improve from one measurement period (e.g., week, month, quarter, or year) to the next.

Objective measurement: Bricks-to-clicks suppliers want to be best-in-class. The Content Analytics platform has built-in criteria that we’ve developed based on industry best practices and ongoing statistical analysis. Suppliers measure themselves against these criteria to make sure they are adhering to these best practices.

Bricks-and-clicks measurement: Bricks-to-clicks suppliers want to match or beat their in-store market share numbers, which they have been investing in for years. Therefore, they often use their in-store numbers as the benchmark for their digital share of shelf and share of search measurements.

Just as important as the metrics themselves, however, is how bricks-to-clicks suppliers put these metrics to work. One key approach across many successful bricks-to-clicks suppliers is widespread, internal reporting done on a regular cadence. For some suppliers that means every day; for others, every week. Regardless of the frequency, the consistency of measurement and distribution of the resulting metrics is core to their approach.

By “reporting” internally on their key e-commerce metrics, our suppliers drive awareness of the importance of e-commerce within the organization. From there, they drive awareness around the importance of what the metrics themselves are measuring such as content quality, placements, inventory, pricing, and, ultimately, sales. By contrasting areas they’re doing well in with areas in which they need to improve, bricks-to-clicks suppliers demonstrate progress while also making the case for further investment. Bricks-to-clicks suppliers create a culture of continuous improvement through ongoing measurement, awareness generation, and business optimization.

Note

In e-commerce, continuous improvement cycles times are fast—measured in days or weeks instead of months or years.

Haven’t many suppliers developed continuous improvement programs in the past? Yes, they have. What’s different in e-commerce is that continuous improvement cycle times are dramatically faster. Bricks-to-clicks suppliers move their businesses to a daily or weekly continuous improvement cycle from a quarterly or annual cycle.

With faster cycle times comes a greater ability to respond to exceptions. There’s no need for a product to stay out of stock for long when inventory can be sourced from multiple locations, even multiple sellers. Prices can be adjusted in near real time. Broken or incorrect product imagery can be updated in minutes if not seconds.

The key to such a high level of responsiveness is being able to respond to these kinds of exceptions quickly. Bricks-to-clicks suppliers who implement a platform like Content Analytics get notified about exceptions and are able to manage them efficiently.

Adopt an MVP Approach

The Lean Startup movement took hold several years ago in Silicon Valley, in the midst of the financial crisis. We’ve found that the most nimble bricks-to-clicks players have adopted this model in their entry into e-commerce. One of the core principles of the Lean Startup movement is the concept of minimum viable product. An MVP is “that version of a new product that allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort.”4 It is not a cheaper version of your actual product but rather a deliverable that enables you to collect the maximum amount of learning.5

How does this concept translate to leadership in e-commerce? Many clients we talk with have been trained to accept (unfortunately) long development cycles, heavy IT investment, and months or years of up-front implementation time before they can take action. Over the years, they’ve had to buy the entire system even though they really just wanted to run a few simple experiments.

When it comes to e-commerce, the MVP approach means being able to gather the maximum learning about what will work best for you in e-commerce with the least amount of effort—and to do so as quickly as possible. Because e-commerce is moving so quickly, our clients can’t afford to spend months or years determining their strategy. They need to act quickly.

Here are a few examples:

One of our suppliers focuses on optimizing a list of 300 key products. Although we have their full product set of thousands of products loaded into our system, by making a concerted effort on the top 300 products, they’ve achieved improvement in out-of-stock rates and content quality very rapidly.

Another global supplier we work with started out by optimizing just 15 items in the grocery category. That may not seem like a lot, but at a company that does nearly $30 billion in revenue annually, changes are often considered only if they’re going to move the needle by at least a billion dollars. MVP allowed the company to do maximum learning with minimum risk.

A third supplier we work with started out wanting to answer the question, could they improve their in-stock rates using our platform? Like other clients, they considered a boil-the-ocean approach but ultimately felt that if they could improve in one area, they could learn how to improve in others. Our work with them has continued in a similar way over time, running additional small e-commerce experiments to streamline their workflows and free them up to focus on selling to their customers—the retailers.

These are just a few of the many examples of how suppliers are using the MVP model to learn in e-commerce. The MVP approach provides them not only with a rapid learning process but with the ability to run multiple “experiments” in parallel.

Just as our bricks-to-clicks clients adopt an MVP approach to learning and experimentation, they also adopt an all-in approach to e-commerce execution based on that learning. They then continue to use the experiments to tune their full-scale effort, using the learning to figure out where to double down and where to cut back.

Embrace the New Path to Purchase

Whether you’re a small supplier with a few dozen products to sell online or a large supplier with tens or even hundreds of thousands of products, embracing the new path to purchase is key. With brick-and-mortar stores, among the hardest parts of selling were convincing a retailer to carry your product and then figuring out how to supply enough inventory so shoppers could see that product on the shelf—or many shelves because there were many physical stores.

Today, nearly anyone can become a seller. You can make a traditional arrangement with the retailer, with the retailer stocking and shipping your products. You can also sell through marketplace s on Amazon, Walmart, eBay, Overstock, and others, or you can get set up as a drop-ship vendor (DSV) .

Like marketplaces, DSV programs have changed the seller landscape, making it easier for smaller and newer sellers to act as virtual first-party sellers on large web sites like Amazon and Walmart. Typically, getting items through item setup as a DSV is easier and faster than making it through a true first-party setup process. With both marketplace and drop-ship approaches, consumers typically receive the product direct from the seller. But with marketplace sales, the seller controls the price (not the retailer), and the fact that the sale is coming from a marketplace seller is made clear on the site via “sold by” text indicating who the marketplace seller is.

Note

With marketplace sales, the seller sets the price, and the retailer takes a fee for the sale. With DSV sales, the retailer prices and sells the item, recognizing revenue for the full price of the product and later remitting the wholesale price to the supplier.

With DSV sales, the retailer prices and sells the item, with the full revenue for the item going to the retailer and then the retailer remitting the wholesale price of the product to the seller later. In a marketplace sale, the retailer takes a fee for the sale.6 Regardless of approach, the process of getting online and selling items is much simpler and faster with e-commerce than it was in the brick-and-mortar world.

While listing and selling has gotten easier with e-commerce, the path to purchase has become more complex. With brick-and-mortar stores, you sourced the product, stocked it, got it carried, and drove demand, in large part through advertising.

With e-commerce, the process doesn’t start when the consumer enters a store, and it doesn’t stop once the consumer makes a purchase. The “path to purchase” is much more extensive. With e-commerce you’re engaging in an ongoing dialogue with the consumer, one that is shaped through price, digital product presence, social influence, and delivery.

Consumers do research online—even if they purchase in-store. They read reviews, check social media, talk to their friends, and build a view on the items and brands they want to purchase. Both online and in-store they continue to research right up until the moment of purchase. And they remain highly connected, with more than 90 percent of consumers using their smartphones while in store.7

Returns are also vastly different online than in stores. Online, a whopping 30 percent or more of all products ordered are returned as compared with 8.89 percent of products purchased in stores. Return rates are even higher during holiday periods, with return rates reaching as high as 50 percent. With almost 50 percent of retailers now offering free returns and 79 percent of consumers stating a desire for free return shipping, returns are getting easier.8

Unlike in-store returns, which have never been the easiest process in the world, e-commerce returns are easy. A prepaid return label often comes included with the original shipping box, and consumers are not against checking prices even after receiving their item and returning it if they find a better price elsewhere. Discount promotions can also play a factor. If a product is cheaper today than it was yesterday, shoppers can easily swap out the product for the same product at a lower price.9

Among other reasons shoppers cite for returning items is that the product they received doesn’t look like the one they ordered online—or they’ve received the wrong product. What’s more, if a product arrives late, doesn’t fit (in the case of apparel), or doesn’t meet expectations in some other way, shoppers are inclined to give a low rating and write a negative review, and this negative review becomes associated with the product, whether the issue was truly the seller’s fault or not.

All of these factors—more sellers competing for the same path to purchase, a greater number of products available, lower switching costs, and more informed shoppers—mean that the path to purchase is more complex online than in stores. With e-commerce, it’s no longer a one-size-fits-all path to purchase. It’s a sophisticated, customized path to purchase that requires long-term, ongoing engagement with shoppers.

Our bricks-to-clicks suppliers invest heavily in delivering the best path to purchase possible with their largest retail partners. But they’re also finding ways to measure and optimize their brand and product presence across the long tail of hundreds, if not thousands, of specialty independent retailers, one of the fastest-growing segments of the retail market.10 That kind of scale can be achieved only with a technology platform like Content Analytics that can provide reporting, manage content, and deliver brand integrity across the many retailers that suppliers don’t have the capacity to support on a one-to-one basis. Bricks-to-clicks suppliers are truly embracing—and leading—this new and highly sophisticated path to purchase.

Summary

The first shopping mall opened in 1956 in Edina, Minnesota, a suburb of the Twin Cities. Since then we have seen the emergence of e-commerce in the mid-1990s and now the seemingly overnight shift in purchasing behavior from in-store to online. The Internet has played a big part, and so too has the widespread adoption of mobile devices and low-cost shipping.

The next generation of shoppers is inherently digital and always connected, creating a more nuanced and significantly more complex path to purchase than ever before. Although the landscape is evolving rapidly, and in many cases because the landscape is evolving rapidly, nimble suppliers, who are open to rapid experimentation, can quickly make the transition from bricks to clicks. In the process, they can maintain, regain, and even establish long-term market leadership positions.