Chapter 6

Counting the Votes: Differing Electoral Systems

In This Chapter

![]() Explaining first past the post

Explaining first past the post

![]() Winning a majority of votes

Winning a majority of votes

![]() Looking at proportional representation

Looking at proportional representation

Elections are a big deal in the UK (and in all democratic countries around the globe for that matter). From deciding which party is to form the national government to who’s going to be in charge of the local council, elections embody the democratic process in all its Technicolor glory.

Although election campaigns can go on for weeks and even months, the vote itself is squeezed into one day when electors are invited to attend a polling station and cast their votes. Election day is the people’s chance to make a difference by saying who they want to represent them, as well as their opportunity to kick politicians out of office who they feel aren’t doing a good job. For election day, read judgement day.

Get your calculator out now, because in this chapter I peer into the polling booths and explain exactly how people elect their politicians.

Listing the Big UK Elections

When you think about British elections your mind probably turns to a general election, with the high-profile national politicians going head to head and the airwaves crackling with all things political. However, the UK has lots of different elections in which you have a right to vote. Here’s a quick guide to the UK’s election scene:

- General elections: These elections are considered the biggies, with seats up for grabs in the UK parliament. Traditionally, these elections have the biggest turnouts and receive the most media coverage. Prime ministers (PMs) used to be able to call elections whenever they wanted, but under a new law introduced in 2010 general elections now occur once every five years, setting in stone five-year fixed-term parliaments.

- Devolved elections: The Scottish parliament and the Welsh and Northern Irish assemblies are big deals to the millions of people living in these parts of the UK. These bodies have lots of powers and in some ways are more important to people living within their compass than the UK parliament. Elections to these bodies take place once every four years and the system used is partly first past the post and partly proportional representation (check out the later sections ‘Coming Up On the Rails: The First-Past-the-Post System’ and ‘Examining Proportional Representation’, respectively).

- Local government elections: From county, parish and community councils to mayors, across the UK almost every year a new set of elections is held. These elections may not have the glamour of a general or devolved election but they’re important, because local government is responsible for many of the nation’s public services, as well as raising council taxes and business rates and approving or turning down planning applications. Chapter 17 has more on the inner workings of local government.

- European parliamentary elections: In some ways European elections shouldn’t be last in this list of elections, because many of the laws governing the life of Britons come from the European Union (EU). Turnout tends to be low – usually only between 30 and 40 per cent of people registered to vote bother to do so – and they take place once every five years, under a complex system called the D’Hondt method (see ‘Dividing in the D’Hondt method’, later in this chapter). The last European election was in 2014, and so the next is scheduled for 2019.

In total, 766 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) sit in the parliament building in Strasbourg, France. Of this number, 73 come from the UK, which slightly under-represents the UK’s share of the total population of the EU. The UK has a population of just over 60 million, which works out to roughly one MEP for every 850,000 citizens, whereas Malta, for example, with its total population of just over 320,000, has six MEPs.

In total, 766 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) sit in the parliament building in Strasbourg, France. Of this number, 73 come from the UK, which slightly under-represents the UK’s share of the total population of the EU. The UK has a population of just over 60 million, which works out to roughly one MEP for every 850,000 citizens, whereas Malta, for example, with its total population of just over 320,000, has six MEPs.

Meanwhile, across the country thousands of party workers go canvassing – trying to drum up support for their party’s candidate by knocking on constituents’ doors, setting up stands in shopping centres, holding public meetings and so on. On election day itself, the polling stations are open from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m., allowing tens of millions of people to vote. The votes are then counted and usually by the following morning the party winning the largest number of seats is clear and it gets to form the next government.

Coming Up On the Rails: The First-Past-the-Post System

The UK parliament is an ancient institution and its members (MPs) are elected by a system that goes back a long, long way.

The number of votes by which the winning candidate wins is irrelevant – just one suffices (as has happened on the odd occasion). More often than not, though, the winning candidate has a majority (the number of votes more than the next finisher) in the hundreds or thousands.

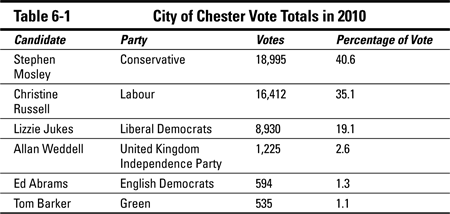

Table 6-1 shows the City of Chester candidates for its member of parliament and the vote totals from the 2010 general election.

The result is that Stephen Mosley (Conservative) won the seat with a majority of 2,583 votes (18,995 – 16,412).

The race theme is also applicable to the forming of a government in parliament. If a party acquires more than 50 per cent of the seats in parliament, it holds a majority – which means that if all the party’s MPs vote in the same way it can’t lose the vote – and the monarch then asks it to form the government.

Looking at the advantages

First past the post has been around for a long time, which means that it must offer something that people like. Here’s what’s good – from some people’s perspective – about first past the post:

- Strong government: A political party can win a majority of seats in the House of Commons without getting a majority of votes cast. For example, in the 2005 general election Labour enjoyed a 66-seat majority but only gained around 40 per cent of all votes cast. Holding a majority in parliament means that the governing party has a virtual free hand to carry out its legislative programme and often leads to a strong government.

Under other systems, such as proportional representation – which I explain in ‘Perusing Proportional Representation’ later in this chapter – parties often have to work together and form coalitions to get legislation through their parliaments.

- Community-centric: Voting for an individual candidate to represent them in parliament allows voters to feel more ownership of their MPs. In fact, although MPs nearly always belong to a political party, they sometimes put the interests of their constituents over that of their party. For example, MPs may vote against their party over plans to close a hospital in the constituency. What’s more, MPs meet regularly to hear constituents’ concerns, regardless of whether the constituents voted for them or not. Under other election methods, such as the candidate list system – see the later section ‘Varying PR: Candidate list system’ – this connection between sitting MPs and their constituents is less strong.

Taking in the disadvantages

Every argument has two sides, and that’s certainly true when considering whether first past the post is right for the country. A lot of commentators simply don’t like the system, because it:

- Often ignores the majority of voters: MPs are regularly elected with a minority of the votes cast. Therefore, a majority of voters end up with an MP that they’ve voted against. Many suggest that this outcome is undemocratic.

- Aids the two major political parties and marginalises minor parties: Apart from the coalition government of 2010 until 2015, and a brief period in 1974 when the Liberals and Labour also formed a short-lived coalition government, for the last 75 years only one of two parties has been in government – Conservative or Labour. The two-party nature of parliamentary election results is no doubt aided by the first-past-the-post system, which makes one party gaining a majority in parliament and thereby forming the government that much easier.

Securing Over 50 Per Cent of the Vote: Majority Electoral Systems

Nineteenth-century US president Abraham Lincoln summed up democracy in his famous 1863 Gettysburg Address by stating that it was ‘Government of the people by the people for the people’. But can any government that attracts less than half the votes cast (which often happens under first past the post, as I describe in the earlier section ‘Coming Up On the Rails: The First-Past-the-Post System’) really live up to Old Abe’s ideal? Many people think not, and therefore some electoral systems are geared towards ensuring that the winning candidate has the support of over half the voters. This section covers three such majority electoral systems.

Laying bare the two-ballot system

- First ballot: Voters cast ballots for their preferred candidates. If one candidate gets over 50 per cent of the votes cast that person wins and no more voting is necessary. But if no candidate gets 50 per cent of the votes, a second round of voting takes place.

- Second round: Only the two candidates with the highest number of votes can stand; candidates who finished third, fourth or lower are automatically eliminated.

The idea is that those who voted for the now eliminated candidates vote for one of the remaining two candidates in the second ballot. Even if they choose not to vote, it doesn’t matter; with only two candidates standing in the second ballot, one of them is certain to achieve over 50 per cent of the votes and thereby win. French presidential elections use this system.

Playing the alternative vote system card

The candidate with the fewest number of first-preference votes is eliminated from the next round of voting. Ballot papers having that candidate marked as first preference are examined and the second-preference selections of those voters are then redistributed to the candidates remaining in the election. If these redistributed votes push one candidate over 50 per cent, that person wins and, again, job done. If still no candidate has over 50 per cent of the votes, again the candidate with the fewest number of votes is eliminated and the second preferences of that candidate redistributed.

This process of elimination and counting second preferences – and, in some variants of the system, the third, fourth and even fifth preferences – goes on and on and, yes, on, until finally one of the candidates breaches the magic 50 per cent of votes cast.

Throwing in the supplementary vote system

If no candidate gets 50 per cent, however, all but the two highest-polling candidates are eliminated. The second-preference votes are added to the first preferences of the two remaining candidates. This process leads to one of the candidates achieving the magic 50 per cent and is a good deal less long-winded than the alternative vote system.

Perusing Proportional Representation

For example, at the 2005 general election Labour, under first past the post, had a majority of 66 seats and yet only won 40.7 per cent of the votes cast. If the election had been run under the PR system, Labour would still have been the biggest party but wouldn’t have come near to obtaining a majority of seats. As a result, in parliament Labour would have been forced to rely on the support of other political parties to see its bills made into law.

Proportional representation doesn’t always result in a coalition government, but it happens more often than not. In order to have a majority of seats in parliament under the PR system, one party has to poll more than 50 per cent of all the votes cast in the country; looking at the history of UK general elections that’s a very difficult task to achieve.

Some people suggest that coalition governments are a good thing, arguing that they prevent one party from pursuing extremist policies. If no single political party has a majority, it has to rely on the support of another party or two to govern and the other parties in the coalition tend to rein in extreme policies.

Most European countries operate a system of PR and so coalitions are commonplace.

Refining PR: Single transferable vote

Strap yourself in again: this variation on PR is another complex electoral system.

If one of them now breaches the quota level, that candidate is elected. After the second candidate has been elected, that person’s preferences are thrown into the mix, leading to other candidates breaching the quota level and being elected.

A slight variant on this process is that, after the second seat is filled, instead of the other preferences from the voters for that newly elected candidate being counted, the candidate who polled the fewest first preferences is eliminated and lower preferences on the ballots for that eliminated candidate are redistributed to the other candidates, all with the object of pushing another candidate over the quota to be elected.

This process continues until all the seats in the region are filled. This voting system is used in the Republic of Ireland – and it’s clearly the one of choice for mathematicians everywhere!

Varying PR: Candidate list system

For example, say ten seats are up for grabs in the whole of East Anglia. Labour and Conservative get 40 per cent of the vote each, while the Lib Dems and the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) receive 10 per cent each. So, out of the ten seats Labour and Conservative get four each and Lib Dems and UKIP each get one.

What about those candidate lists? Well, Labour and Conservative see the first four candidates on their lists elected and the Lib Dems and UKIP only the name at the top of their list. Under this system, electors are voting for political parties rather than individuals.

Dividing in the D’Hondt method

Here’s a simple example of a fictional region I call Mercia. Out of 935,000 votes cast, the political parties finish up with the following number of votes:

- Labour 400,000

- Conservative 300,000

- Liberal Democrat 110,000

- Green Party 75,000

- UKIP 50,000

Under the D’Hondt method, the region’s five seats are distributed as follows:

- Seat 1 goes to Labour: It has the highest number of votes and the candidate at the top of its party list is a new MEP. Halving Labour’s total vote tally results in the following numbers:

- Conservative 300,000

- Labour 200,000

- Liberal Democrat 110,000

- Green Party 75,000

- UKIP 50,000

- Seat 2 goes to the Conservatives: Its vote tally is halved (again the candidate at the top of its party list is now an MEP), and for seat 3 the votes stand as follows:

- Labour 200,000

- Conservative 150,000

- Liberal Democrat 110,000

- Green Party 75,000

- UKIP 50,000

- Seat 3 goes to Labour: The candidate second on Labour’s party list is now an MEP. Its voting tally is halved again:

- Conservative 150,000

- Liberal Democrat 110,000

- Labour 100,000

- Green Party 75,000

- UKIP 50,000

- Seat 4 goes to the Conservatives: The second candidate on the party’s list is now an MEP. The Conservative’s tally is again halved:

- Liberal Democrat 110,000

- Labour 100,000

- Green Party 75,000

- Conservative 75,000

- UKIP 50,000

- The final seat goes to the Lib Dems.

If more than five seats were up for grabs, the process of distributing seats and filling them with candidates from the party lists goes on and on, with even the Greens and UKIP likely to get an MEP. Contrast this scenario with the first-past-the-post system (see the earlier ‘Coming Up On the Rails: The First-Past-the-Post System’ section) in which neither of these parties would win a seat despite the fact that, between them, they command around 15 per cent of the total votes cast in Mercia.

Looking North and West to the Additional Member System

The additional member system, used for elections to the Scottish parliament and the Welsh assembly, combines the basic fairness of PR with the representative benefits of first past the post. Voters, as a result, still feel a connection with the person they elect to represent them.

So if, for example, the Scottish National Party (SNP) gets 40 per cent of second votes cast across the country, it receives 40 per cent of what are called additional members (additional to the people elected through first past the post as constituency MSPs). As for who gets to sit as these additional members, names are drawn from lists of individual candidates submitted by the political parties.

Of 129 MSPs, 73 are elected via first past the post and 56 through the additional member system.

Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish electors not only get to choose who sits in their own national parliaments and assemblies, but they also have an MP who they elect, through first past the post, to the UK parliament in Westminster.

UK general elections are pure theatre. The monarch officially dissolves parliament – which makes the king or queen sound like some dastardly Doctor Who villain but in reality just involves signing a piece of paper. When parliament is dissolved all the MPs return to their constituencies to campaign for re-election. This period is called the short election campaign and lasts between three and six weeks. During this campaign, politics receives almost blanket coverage across the media, with politicians being quizzed by journalists and debating policy with each other.

UK general elections are pure theatre. The monarch officially dissolves parliament – which makes the king or queen sound like some dastardly Doctor Who villain but in reality just involves signing a piece of paper. When parliament is dissolved all the MPs return to their constituencies to campaign for re-election. This period is called the short election campaign and lasts between three and six weeks. During this campaign, politics receives almost blanket coverage across the media, with politicians being quizzed by journalists and debating policy with each other. This long-used system is commonly known as first past the post, because it has all the characteristics of a race. Here’s how the system works in general elections to the UK parliament and in local councils: voters cast their ballots on election day, putting an X by the name of the candidate they want to elect. All the votes are counted and the individual with the largest number is declared the winner.

This long-used system is commonly known as first past the post, because it has all the characteristics of a race. Here’s how the system works in general elections to the UK parliament and in local councils: voters cast their ballots on election day, putting an X by the name of the candidate they want to elect. All the votes are counted and the individual with the largest number is declared the winner. A constituency where the winning candidate enjoys a very large majority – over 10,000 votes – is referred to as a safe seat. On the flipside, a constituency where the winning candidate has a small majority is known as a marginal.

A constituency where the winning candidate enjoys a very large majority – over 10,000 votes – is referred to as a safe seat. On the flipside, a constituency where the winning candidate has a small majority is known as a marginal. The prominent Labour turned Liberal Democrat politician Roy Jenkins (1920–2003) was a long-standing proponent of reforming the UK electoral system. After a long career in politics, Jenkins was asked by new PM Tony Blair in 1997 to produce a report on reforming parliamentary elections. Unsurprisingly, Jenkins recommended getting rid of first past the post and replacing it with proportional representation. Blair, equally predictably, ignored the recommendations of the report because he owed his majority in parliament to the first-past-the-post system. Even at its most popular, Blair’s Labour Party never polled more than 43 per cent of all the votes cast in a general election.

The prominent Labour turned Liberal Democrat politician Roy Jenkins (1920–2003) was a long-standing proponent of reforming the UK electoral system. After a long career in politics, Jenkins was asked by new PM Tony Blair in 1997 to produce a report on reforming parliamentary elections. Unsurprisingly, Jenkins recommended getting rid of first past the post and replacing it with proportional representation. Blair, equally predictably, ignored the recommendations of the report because he owed his majority in parliament to the first-past-the-post system. Even at its most popular, Blair’s Labour Party never polled more than 43 per cent of all the votes cast in a general election.