OTHER ARTHROPOD ADVENTURES

Insects are the most abundant arthropods, but there are others you will encounter and enjoy getting to know. Arthropod means “jointed foot.” These insects have segmented bodies of more than one part; some have many legs, an exoskeleton, and are cold blooded. Arthropods include insects, spiders, centipedes, millipedes, scorpions, ticks, shrimp, barnacles, crabs, and many more.

|

CENTIPEDES & MILLIPEDES: SPEED & DIET |

In this lab, we examine two common myriapods—centipedes and millipedes—and determine how fast they can move or run. Is their locomotion, including number of legs, related to their diet?

MATERIALS

• Critter keeper

• Camera that records video

• Small stick

• String

• Ruler

• Your field notebook

• Pencil

• Lab partner

• Timer

Young entomologists seeing how fast centipedes can run!

MEASURING CENTIPEDE SPEED

STEP 1: Find a centipede (fig. 1) and coax it into your critter keeper. Use your camera to record a video while you touch a centipede in a critter keeper with a small stick. They are very fast and deliver a surprising bite—keep your hands out of their reach! Watch your video and lay a piece of string over the path it ran. Measure the string. Play the video again and measure how long it lasts in seconds. Divide the number of inches (cm) of the string by the number of seconds to determine how many inches (cm) the centipede moved per second. Record your results in your field notebook.

Fig. 1: Redheaded centipede with two legs per body segment

MEASURING MILLIPEDE SPEED

STEP 2: Find a millipede (fig. 2) and place it in your critter keeper. Millipedes won’t respond to being touched by a stick, so you may need to wait until yours is actually crawling to do this experiment. Because a millipede is much slower, you can place the string on its path behind it as it crawls. Be sure to measure the time it is crawling. Measure the string that represents the path and divide the number of inches (cm) by the number of seconds your millipede crawled to determine how many inches (cm) it moved per second.

Fig. 2: Millipede with four legs per body segment

A COMPARISON

STEP 3: Get a lab partner to time you as you run across the room as fast as you can. Now, crawl across the room as fast as you can while your friend times you. It is easier to see that the (carnivorous) centipede with only two legs per segment can chase down its prey faster than a millipede with multiple legs per segment. The millipede is a plant eater, and it is a good thing it does not need the speed of the centipede to catch its dinner!

|

WHAT DO ISOPODS LIKE? |

Isopods, or rolypolies, are commonly available and easy to use in experiments. You can collect isopods for experiments from under rocks, logs, leaves, mulch, flowerpots, and pieces of bark—or even a cardboard box left in the yard. In this activity, we determine a rolypoly’s preferences for light or dark, and moist or dry habitats.

MATERIALS

FOR WET VS. DRY ENVIRONMENTS

• Petri dish or small plastic container

• Paper towel

• Scissors

• Timer

FOR LIGHT VS. DARK ENVIRONMENTS

• Small piece of cardboard or index card

• Petri dish and isopods (from wet vs. dry experiment, listed above)

• Your field notebook

• Pencil

A sow bug (above) and pill bug (below). Sow bugs cannot roll into a ball, but pill bugs can.

ROLYPOLIES: WET OR DRY ENVIRONMENTS?

STEP 1: Cut pieces of paper towel to the size of the container. If the container is round, place the paper towel in it and moisten one half of the towel. If the container is square or rectangular, place pieces on both sides of the container with a little space between them.

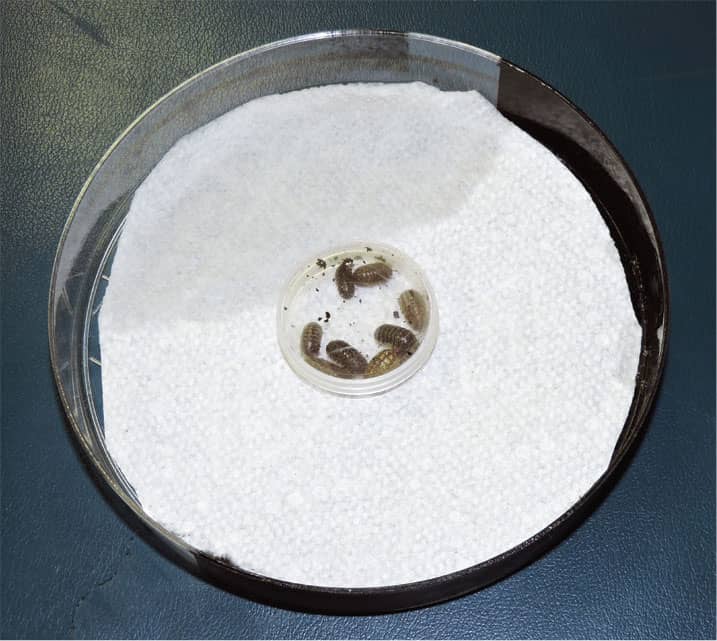

STEP 2: Release the isopods in the area between the wet and dry areas (fig. 1). Give them 15 minutes to learn their way around and decide which side to remain on.

Fig. 1: In a clear plastic kitchen container with a lid, place your isopods in the center of the paper towel with one side moistened.

STEP 3: Where did they go? Isopods are kin to shrimp and use book lungs (respiratory organs) to breathe. They must remain moist for gas exchange to occur. Record your results in your field notebook.

ROLYPOLIES: LIGHT OR DARK?

STEP 1: Place a piece of cardboard over half of the container. Place isopods in the center of the container—not under the cardboard (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Isopods, like shrimp, must remain moist for gas exchange to occur, and so prefer the dark moist area.

STEP 2: Place the roly-poly experiment in the sun.

STEP 3: Monitor to see whether they enjoy the sun or seek shelter under the cardboard (fig. 3). Record your observations in your field notebook.

Fig. 3: Cover your isopods (black paper, tented cardboard, or painting the lid a dark color all work).

|

ADOPT & FEED AN ORB WEAVER |

Having a pet spider that lives outdoors near your house makes an incredible companion! Spiders are fun to watch and feed, and they also trap undesirable bugs. The black and yellow garden spider is a beneficial arachnid to have around, and, if you’re lucky, her spiderling descendants will continue trapping small insects and entertaining you and visitors for years!

MATERIALS

• Your field notebook

• Pencil

• Camera

STEP 1: Look for a spider to adopt (fig. 1). They are often found under the eaves of houses or other buildings. If you can’t find the black and yellow garden spider, look for another type.

Fig. 1: A black and yellow garden spider behind her stabilimentum (zigzag)

STEP 2: Periodically, but not too often, collect and throw live insects into her web (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Feeding an Argiope spider

STEP 3: Make careful observations and take photos of bugs trapped, or thrown, into her web, the smaller male’s appearance, egg sacs, etc. Sketch her web in your field notebook. Date your observations.

STEP 4: There is more to discover—continue making observations over time and record them in your field notebook.

|

WOLF SPIDER MOMS |

Wolf spiders are relatively common, large spiders. The males are smaller; the females are very protective of their spiderlings. The young ride on their mothers’ backs. This is what you will be on the lookout for in this activity.

MATERIALS

• Your field notebook

• Pencil

STEP 1: Walk around your neighborhood and ask neighbors to report back to you if they spot any spiderwebs. When you find a wolf spider that looks like it has a hairy back, look more closely—you may be seeing many spiderlings (fig. 1)! With her keen eyesight, Momma Wolf Spider will be watching you, too. It is common to find them in homes, but don’t hurt them.

Fig. 1: A wolf spider with spiderlings on her back

STEP 2: Very slowly and gently tap her with your finger or a pencil to dislodge a few spiderlings. They will run around and she will freeze, waiting to make sure it is safe before continuing.

STEP 3: When she decides you are not a threat, she will stand up tall on her legs signaling for her spiderlings to climb back on, and then she will be on her way. This is incredible to watch. Describe your observations in your field notebook.

STEP 4: If you have observed this indoors, take a piece of paper and gently scoop the mother and her spiderlings into a cup or bowl and take them outside to release.

|

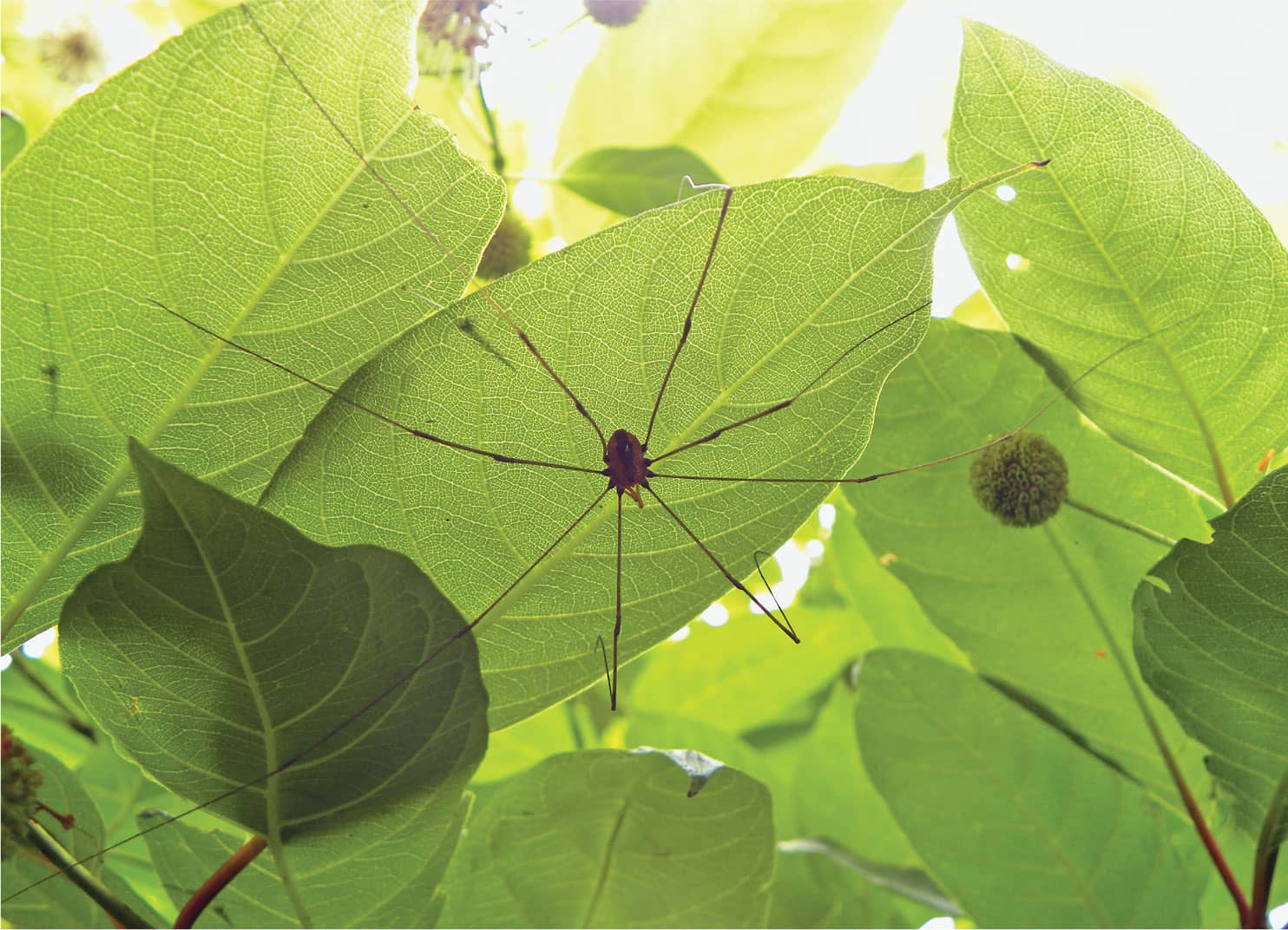

GRANDDADDY LONGLEGS: AN UNDESERVED REPUTATION |

These guys are common enough that you will enjoy amazing your friends with your Opilione (order name) wrangling ability! This activity is best done in front of a large audience of your friends. While they’re all backing off, telling you how “poisonous” these “spiders” are, you can share what you have learned.

MATERIALS

• Small stick

• Your field notebook

• Pencil

• Black light (inexpensive black light flashlights are available at big box stores)

STEP 1: Find a granddaddy longlegs (fig. 1). Go ahead, pick it up (fig. 2), and let it walk around on your hands. Watch for some defensive behaviors—bobbing or vibrating their bodies or playing dead.

Fig. 1: A granddaddy longlegs under a leaf.

Fig. 2: Go ahead—don’t be afraid to hold a granddaddy longlegs.

STEP 2: They have scent glands and, if they should use them (they have a smell), collect some on a stick and look for an ant trail. Draw a line across the trail with this secretion and see if it deters the ants. Record your observations in your field notebook.

STEP 3: In the unfortunate event your Opilione loses a leg, instruct those with you to watch the leg carefully. “Pacemakers” located in the long femur repeatedly signal the muscles to extend the leg, and the leg relaxes between signals. Some think this may distract predators.

STEP 4: Some species produce a fluorescence when exposed to ultraviolet, or black, light. Use a black light flashlight to find out (fig. 3). Does yours?

Fig. 3: A black light flashlight. Do not look directly at the light from a black light flashlight.

SAFETY FIRST!

SAFETY FIRST!

NEVER LOOK directly into the light made by a black light flashlight. The ultraviolet (UV) light may damage your eyes!

|

BUG FEAST! |

Next time you have a seafood dinner, eat the bugs, examine their parts, and sketch them! Crawfish, crabs, shrimp, and lobster are all arthropods. Entomophagy is the practice of eating insects, and about 80 percent of the people on Earth eat insects!

MATERIALS

• Your field notebook

• Pencil

STEP 1: Keep a record of the arthropods, including shrimp, lobster, crab, and crawfish, that you eat in your field notebook. Include a sketch of each.

STEP 2: Describe the experience and the flavor.

STEP 3: Start a list in your field notebook of insects and other arthropods you see for sale as human food. Insect zoos, bug festivals, and bug camps often feature edible insects. Novelty stores often sell suckers with arthropods and other insects, including crunchy crickets, chocolate-covered crickets, and others, imbedded right inside (fig. 1). You might also see mealworm rice treats (fig. 2) and insect brittle! When you try an edible insect, make notes in your field notebook, including your reaction and its taste, along with a sketch.

Fig. 1: A cricket lollipop

Fig. 2: Mealworm rice treats

STEP 4: Contact the entomology department at a university near you to see if they have a professor or specialist involved in entomophagy—the practice of humans eating insects (fig. 3). There may be events in which you can participate. If no university is nearby, many novelty stores in malls sell insect treats and they are also readily available online for you to try.

Fig. 3: Dr. Guyton (the author) cooking mealworms