INTRODUCTION

If you’re reading this now, it’s likely that you want to bring people together in a new or more powerful way. Kudos to you. The world needs more people like you. We wrote this book to make you more effective, become a stronger community leader, and help you avoid bad and potentially hurtful mistakes.

Over years, miles, and time zones, many people have approached us seeking help to build communities for their organizations. This includes numerous schools, political advocacy groups, professional collectives, religious organizations, and, of course, for-profit companies spanning the globe. All want to invest in bringing together the people important to them. These include employees, customers, colleagues, political and artistic collaborators, and volunteers. These leaders all aspire to build a community that serves both their organization and the envisioned members. Doing this in a way that honestly enriches members and delivers organizational benefits looks like mystical enchantment to many.

Many professional community managers have also shared their longing for something that articulates what they already do and for wisdom to make them better.

Both the words community and brand lack singular definitions in leadership writing. Although several definitions may be useful in differing contexts, the discrepancies create much confusion. We use our own working definitions in this book.

We define a community as a group of people who share mutual concern for one another. A brand is any identifiable organization that promises value, no matter its size or mission. A brand can serve for-profit, nonprofit, political, social, artistic, faith-based (or any other) purposes.

It follows that a brand community is any (real) community that aspires to serve both members and (at least one) organizational goal.1 They’re often started by, inspired by, or managed by an established organization, but not necessarily so.

Although brand communities will (1) look and feel very different from one another, (2) work toward different goals, and (3) address different maturity stages, many core principles remain the same no matter where or who makes them, or what their purpose. You will recognize these principles by the end of this book.

Many aspiring leaders don’t even know how to articulate the ways imagined communities will serve their organization. They often assume that community is (probably) better than no community. It’s also often hard for them to articulate how their community will enrich members within it.

We’ll discuss the most common ways authentic communities serve organizational goals and thus warrant meaningful investment:

- Innovation: creating new value for stakeholders

- Customer and stakeholder retention: keeping customers and stakeholders involved with the organization and providing value to the brand

- Marketing: informing the market of offered value

- Customer service: helping customers/users with the brand service or products

- Talent recruitment and retention: attracting and retaining the people your organization needs for success

- Advancing movements: creating a fundamental shift in the culture or business

- Community forum: making the brand a destination for a specific community

Building Community (versus Promotion and Mobilizing)

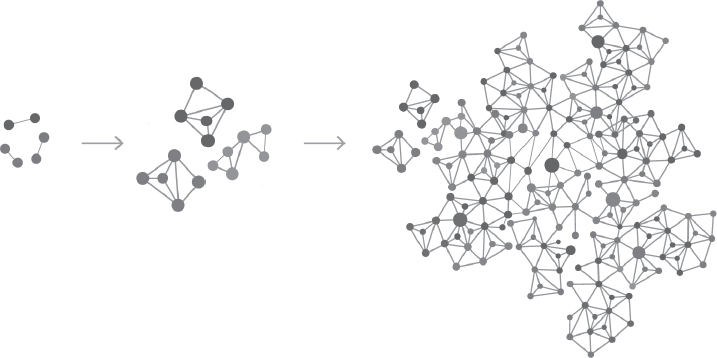

We use the term building community to mean facilitating, accelerating, and supporting the individual relationships that together form a community. Authentic community building is a pointillistic endeavor. A community exists as a network of relationships made up of participant pairs feeling trust and appreciation between them. Each relationship is like a “point” in our bigger view of community. If we facilitate enough authentic interconnected relationships and nurture them over time, we create a community. We think of this metaphorically as growing relationship threads that knit together into community. (See figure I.1.)

Some resources use the term building community to refer to promoting events or mobilizing groups. This includes instructing organizations in what social media platforms to leverage, posts to write, and photos to share (promotion), and how to leverage established connections to coordinate action (mobilize). Although both promotion and mobilization can be compatible with community building, and are often important, we make a distinction between each activity, for several reasons.

First, tools and strategies for promoting are well known and accessible. Please use the best honest tools to promote your events and community programs.

FIGURE I.1. The Network of Connections

Second, you can both promote many events and mobilize thousands of people while building little or no community. Film screenings, park concerts, and trash pickup days do this all the time, with no criticism from us. For community builders, focusing too much on promotion or calls to action can mean overlooking the principles that grow connections when and where people show up.

Third, believe it or not, public promotion isn’t always necessary for a successful brand community. Many robust communities don’t need to promote or even grow membership. We know of brand communities that remain invitation-only and keep the admission process secret. They know that size and intimacy are inversely related, and they want a tight-knit, effective, dare we say “elite” membership.

Unfortunately, many mistakenly believe that if you just bring people together (e.g., at a concert or bar), enduring relationships naturally form. Although you may get lucky, this rarely happens without proper supporting principles at play.

Our Lonely Era

Research indicates that you (and everyone you know) live in the loneliest era in American history. Nearly half of Americans report sometimes or always feeling alone. One in four Americans rarely or never feel as though there are people who understand them. And two in five Americans sometimes or always feel that their relationships are not meaningful and that they’re isolated from others.2

This isolation trend has been getting worse.3 Teens in the US today are now “less likely to get together with friends in person, go to parties, go out with friends, date, ride in cars for fun, go to shopping malls, or go to the movies” than the generations before them. To be clear, teens do gather differently, but they are more isolated overall than seemingly ever before.4

The trend is sharply affecting mortality rates. When we look at large populations, there is a positive relationship between loneliness (disconnection) and suicide.5 Said bluntly, the more loneliness, the more suicide. Teenage suicides are at an all-time high.6 In fact, the number-two cause of teenage death in the US is suicide. The number-one cause is accidents, which includes all car, firearm, drowning, and poisoning events combined.7 The rising rate of suicide, although affecting certain groups and intersections of groups more than others, is occurring across gender, class, and ethnic categories. We live in a time when the wealthy city of Palo Alto, California, must create a Track Watch program to hire patrolling security guards to prevent teenage suicides along rail lines.8

Loneliness at Work

The growing loneliness trend doesn’t apply just to our teenagers. We Americans spend more time at work than with our families. Yet loneliness at work is such a crisis that the Harvard Business Review has published a front-page article with the unsubtle title “Work and the Loneliness Epidemic: Reducing Isolation at Work Is Good for Business,” by former US surgeon general Dr. Vivek Murthy. Research indicates that “strong social connections at work make employees more likely to be engaged with their jobs and produce higher-quality work, and less likely to fall sick or be injured. Without strong social connections, these gains become losses.”9

Research also indicates that there is a link between loneliness and low organizational commitment among professionals in fields as diverse as hospitality, education, and medicine.10 Lonely people disengage, and such disengagement costs organizations of all types in many ways, including “almost 37% higher absenteeism, 49% more accidents, 16% lower profitability, and a 65% lower share price over time.”11

Our work-based communities are disintegrating. Among non-self-employed Americans, the number of those who regularly work at home has more than doubled since 2005, and these workers frequently state loneliness is a major concern.12

Moreover, loneliness has profound health effects. Loneliness is as bad for your body as smoking as many as fifteen cigarettes a day.13 It causes stress and thus elevation of the stress hormone cortisol, which at high levels is connected to inflammation, heart disease, digestive problems, and sleep regulation problems, among many others. Loneliness can erode our thinking, including our analytical ability, concentration, memory, decision-making skills, and emotional regulation.14 So if you care about the people you work with (socially, professionally, politically, philanthropically) remaining emotionally, mentally, and physically capable, then attending to how connected your teams grow is important to you too.

Technical and Digital Context

Despite this reality, when we speak to Americans, most mistakenly think that we’re in a more connected era because of the new digital tools for reaching others. The truth is, we’re all far less connected and way more distracted. Distraction caused by digital devices is so powerful that just putting our digital devices in our view distracts us from full enjoyment in social interactions.15 Research indicates that even using digital devices for conveniences (such as Googling walking directions rather than asking a stranger) reduces social connection.16

Those who turn to digitally connected communities for relationships experience at least two shortcomings that often go unresolved. The first is that most social media “connections” are, at best, only weak ties. And every minute spent entertaining weak ties is possible time taken away from creating or deepening strong ties. Over years, the distraction of social media–based weak ties radically changes the number of strong friendships we can turn to when we need friends most. These needs range from pet-sitting to shoulders to cry on.

Charles, for example, has more than fifteen hundred “friends” on one social media account. Far fewer than one hundred showed up to help him move across the country. He’s not confused about the difference between real and social media friends.

There are many well-intentioned organizations that “connect” citizens and neighbors to share information such as local crime incidents, town hall events, and civic alerts. They serve real needs and provide convenient, even lifesaving information. But let’s recognize that past generations received similar information from friends and neighbors in regular conversations. They met new neighbors by knocking on their doors. Although new technology offers a lot of information, relying on these tools doesn’t grow the relationships that used to form among citizens and neighbors.17 Either we learn to invest differently in such relationships, or they won’t form.

Organizations Want to Invest

Smart for-profit and nonprofit organizations recognize that there is a widespread hunger for connection and are investing to address it. Many seek a way to profit by addressing the new isolation.18 We don’t object. We do object to the amount of rhetoric about community compared to actual community building.

Marketing departments and C-suites continue to use the term community to label wide-ranging organizational investments, including neighborhood events, charity partnerships, online forums, and even simple email lists. But a closer look reveals that most (and sometimes all) of the community-building measures are superficial or even irrelevant to real community.

In fact, the term community has been used by brands to refer to so many ideas over the past twenty years that the word has lost whatever shared meaning it once had—a loss for the organizations as well as the individuals within these so-called communities. We call these so-called communities mirage communities: groups that organizations may label as communities, but that a trained eye can recognize are not. (We will discuss mirage communities further in chapter 1.)

When we ask individuals inside organizations how they define community and how they understand its importance for their roles, most are hard pressed to define the term for their work. Often the best they can come up with is, “Community is good for people.” The answer is hollow at best and meaningless at worst.

Although brand communities do not and will not totally resolve this era’s isolation crisis, they can address many hungers:

- How individuals grow and form friendships that support one another

- How we grow beyond our own individual and team limitations

- How we restore feelings of agency and efficacy

- How we gather to form meaningful relationships

- How we set up future generations to avoid our era’s loneliness

Although successful brand communities must serve organizational goals, to build an effective brand community, you must begin by rejecting the premise that everything an organization does or offers must serve profit or exist in a transaction. Real communities are made up of relationships. Always. Relationships exist in the realm of personal experience, and although they may include transactions, they are never purely transactional. They include some generosity, at least the kind where we help others without calculating the return on investment (ROI) for sending a card, answering a timely question, or holding a door open for a stranger coming in from the cold. Said differently, community relationships transcend transaction.

People don’t commit to, feel safe in, or extend themselves for relationships that only serve a person (or brand) “getting” something as cheaply and easily as possible. We commit to relationships where we believe that others care about our success too.

In real community, members help one another become who they want to be. This can include sharing information, skills, hard-won lessons, and, very often, attentive friendship. When a brand can offer this to members (customers, users, staff, colleagues, volunteers), then something much richer and more rewarding can develop.

Brand Communities in the World

Let’s consider some real-world examples of brand communities that made a difference for organizations that invested in connecting people important for their success.

Twitch

Twitch is the largest online gathering space for people to watch and stream live digital video broadcasts. Over two hundred million people visit it each month to see over one million broadcasters.

Twitch’s business depends on a two-sided marketplace. That is, the brand needs successful broadcasters to use the Twitch platform to reach audiences, and Twitch needs many more viewers to return to the platform for content. Marcus Graham, Twitch’s director of creator development, understands that to make the business work, both broadcasters and viewers need to understand and feel that they belong in the Twitch community. In fact, helping them recognize that Twitch provides supportive and responsive relationships is Twitch’s competitive advantage over other broadcasting platforms. Twitch therefore invests in big events and countless small actions so that users feel seen by and connected to one another and to Twitch staff.

The brand hosts two annual conventions, called TwitchCon, which bring together tens of thousands of users into a shared space. As Marcus put it, “TwitchCon ensures what is transactional online can grow into moments of connection and belonging. It’s a physical manifestation of our online world. When flesh and blood is pulled out of the internet and into a physical location, something magical happens” (personal communication with Marcus Graham, July 2019).

At a TwitchCon presentation in 2018, the company shared the importance of collaboration for the whole brand and how Twitch broadcasters (media creators) collaborate in rich ways: “Twitch is a place where broadcasters aren’t competition; they’re collaborators.”

Twitch’s Erin Wayne explained that Twitch needed to ensure that members accurately see themselves as part of the organization. Representing them had to be accurate in terms of both information and tone. She noted that it was a challenge to highlight and celebrate member collaborations authentically in the context of a corporate voice (personal communication with Erin Wayne, October 2019).

To meet this challenge, Twitch turned to broadcasters 88bitmusic and BanzaiBaby to lead a creative project to celebrate and highlight Twitch collaboration. In four weeks, the members gathered costume designers, musicians, composers, camera operators, and all the needed talent for a professional-grade video celebrating collaboration in the Twitch community.19 The volunteers even created a brand-new game for all to play at TwitchCon. At the end of the video, each member of the collaboration was highlighted for their role. The creative work and quality stunned Twitch leadership, and Twitch was able to share media with a truly authentic message.

Twitch leaders discovered that members were “ecstatic to contribute,” and the project opened their eyes to the possibility of using members rather than outside agencies to address the growing company’s creative needs. They saw that no outsider could better understand and share what makes Twitch special than their own present community.

Twitch helps us understand how an organization can tap into and return to unique resources by binding together members who gather around shared values.

The United Religions Initiative

The United Religions Initiative (URI) is a global interfaith network of organizations and individuals promoting interfaith cooperation to end religiously motivated violence.20 Twenty years old, the organization includes more than a thousand Cooperation Circles (member groups) in over one hundred countries. URI-connected projects touch on leadership development, environmental protection, justice, and interreligious harmony. URI provides a support network to local grassroots leaders. These leaders often work in places with deadly interfaith conflict.

Sister Sabina Rifat, URI coordinator for women in Pakistan, was invited to lead an interfaith program for both Muslim and Christian women in the Mirpur Mangla province within the Kashmir region. She wanted to empower and educate local women there in several ways: (1) by teaching them skills to grow as area leaders even though they live mostly within their homes; (2) by inspiring and demonstrating interfaith harmony; (3) by encouraging them to “struggle” for their daughters to get better educations than they got for themselves; and (4) by practicing the freedom to work together with Christians, Muslims, Hindus, and other sects and castes.

But the event was a five-hour drive from her home in Lahore and was in an area with ongoing religious conflict. Sr. Sabina feared the trip both as a single woman traveler and as a Christian woman visiting a majority-Muslim province to encourage women’s leadership.

Then Ahmad Hussain, chair of the Inter-Cultural Youth Council, Islamabad, another URI group in Pakistan, came to her assistance. He learned about Sr. Sabina’s invitation and security concerns through another member of the URI community. He then offered to accompany her as a supportive Muslim man and remain with her as she traveled within the province. Sr. Sabina accepted this offer, which made her visit with the Mangla women possible. The URI community also connected her with a local Kashmir family who fed her in their home in daytime even during their own Ramadan fasting. The reliable connection among members of the URI community in Pakistan gave Sr. Sabina security and confidence, and it enabled her outreach to women in a remote part of Pakistan. Sr. Sabina reported that approximately one hundred Muslim and Christian local women participated in that first gathering bringing them together.21

Her experience is a fantastic example of individuals and an organization growing more powerful in pursuing a goal when members are connected by far more than a quid pro quo or transactional relationship.

Harley-Davidson Motorcycles

The Harley-Davidson motorcycle company was founded in 1903. In 1969, it came close to bankruptcy. New investors moved Harley’s production from Wisconsin to Pennsylvania, fired employees, and neglected both product development and quality control.22 The company couldn’t compete with new Japanese products, and Harley had used an unreliable “shovel-head engine” that disappointed customers.23 By 1981, the company hadn’t rebounded much, controlling less than 5 percent market share. That’s when internal executives bought the company back because no other buyers wanted the firm.24

On January 1, 1983, just after inking the buyback deal, Harley executives rode together to return the company headquarters from Pennsylvania to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Along the way, they invited Harley customers to meet them. Some consider this trip the first ride of the Harley Owners Group (HOG) program. Former vice president of business development Clyde Fessler would later say of HOG aspirations, “We thought we’d get about 25,000 people nationwide, sell a few patches, sell a few pins and have a good time.”25 He was wrong.

In the first year alone, more than thirty thousand members joined a HOG chapter.26 Literally tens of thousands of riders connected with others longing to get out on a Harley bike, meet new friends, and enjoy the freedom of the road. The nascent group offered group rides, HOG “Fly & Ride” privileges that allowed members to rent and ride a Harley on distant vacations, a HOG magazine, and pins, patches, and collectibles.27

The next year, 1984, Harley launched the first HOG rallies in Nevada and Tennessee, with combined attendance of about three thousand. A year later, in 1985, HOG exceeded sixty thousand members in forty-nine chapters.28 It quickly became the world’s largest motorcycle club.

Harley dealers around the world live and die by customer enthusiasm for Harley gear. All could see that Harley indeed had a robust, excited, and accessible following.

In 2003, the formerly almost bankrupt company earned a record profit of $1 billion. By 2006, the company held a 65 percent market share, more than four times that of its next-biggest competitor, Honda.29 In 2012, HOG reached over one million members in one hundred countries. Former Harley CEO Rich Teerlink would go on to report that “perhaps the most significant program was—and continues to be—the Harley Owners Group (HOG).”30

Harley built a community of customers who wanted to find one another for support, fun, and growth and were perhaps waiting for someone to invite them in. When the company built relationships with these customers, it had access to the very people who wanted to help it innovate in its field and share the brand’s excitement worldwide. Harley-Davidson helps us recognize that even struggling brands may have much goodwill available to them if they can bring fans together in relationship.