12. Circular business models

The linear economy is based on manufacturing products, selling them to a consumer, who then consumes them and is responsible for disposing of them at end-of-life. The circular economy needs new business models to retain the value of products and to help to close the loop.

The business models range from full performance-based models through to take-back and remanufacture. In the performance-based models, the manufacturers retain ownership of the products whilst providing a service to the customer. The take-back model proposes selling products that are designed to be returned and remanufactured with incentives such as deposits, or guaranteed buy-back, to encourage customers to return the used products when no longer required.

Performance not Products

Walter R. Stahel has long promoted the concept of selling performance rather than products, so the consumer becomes a user and ownership is replaced by stewardship. There is an increasing shift towards selling performance over purchasing products, with people leasing printers, cars, office space and even clothes (e.g. Mud Jeans). Selling performance means that the manufacturer retains ownership of the materials, therefore securing their supply of components and materials in the future. This helps to maintain the value of the components, as manufacturers are more likely to:

- design their durable products to have a long service life with the ability to repair and upgrade, or even remanufacture them

- design their consumable products to be simple to disassemble and recycle, or to return to the biosphere

- ensure that toxic materials are easy to separate and reclaim for reuse, or are designed out of the products.

These arrangements can be good for businesses, as they create long-term relationships between manufacturers and customers, rather than one-off interactions.

RAU Architects and Turntoo

Thomas Rau’s design philosophy rests on the premise that the planet is a closed system and that there are a finite amount of resources available with no new places to put the waste that is generated. His designs aim to make best use of materials and resources to respect the balance between humans and the physical environment. Rau proposes that humans should behave as guests on the planet, rather than owners of it. One way to realise this in building and product design is to shift away from ownership and towards stewardship. Owning products brings responsibility for their upkeep and ultimate disposal, which is problematic when many products are full of materials that are unidentified and difficult to reclaim as an equally valuable element.

As part of the drive towards optimising the use of materials, Rau has implemented the use of service models and as well as leasing services in some of his buildings (see Brummen Town Hall case study in Chapter 11), and he has set up a company called Turntoo that facilitates service-based contracts between manufacturers and users. The idea of Turntoo is that the manufacturer retains ownership of the products and the consumers only pay for the performance, rather than the raw materials that go into the product. This creates a closed loop with the materials and components of the product remaining in a ‘raw materials cycle’ whilst the service offered by the product is agreed with the customer.

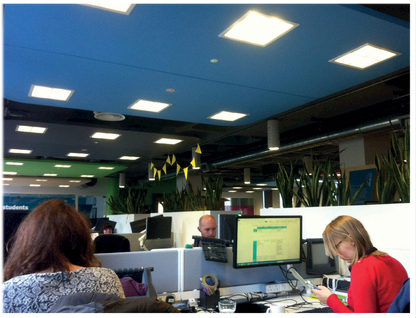

Based on this concept, Rau approached Philips lighting and proposed that they offered him a lighting service instead of purchasing lamps and control gear. The idea developed into Philips’ ‘Pay-per-lux’ model, which was pioneered in RAU Architects’ own offices in Amsterdam and subsequently in Brummen Town Hall. The Pay-per-lux model is a performance-based arrangement where Philips installs and maintains a lighting level and monitors the lighting performance and energy use online with annual reporting, health checks and preventative maintenance. Furthermore, Philips pays the energy bills for the lighting, which gives them the incentive to provide the most efficient lighting system and to ensure that it is operating as well as possible.

As Thomas Rau says: ‘I told Philips, “Listen, I need so many hours of light in my premises every year. You figure out how to do it. If you think you need a lamp, or electricity, or whatever – that’s fine. But I want nothing to do with it. I’m not interested in the product, just the performance. I want to buy light, and nothing else.”’1

The model was re-conceived by Philips in the UK specifically for the National Union of Students.

Macadam House, London – Pay-per-lux

When the National Union of Students (NUS) set about refurbishing an old 1960s building into its new headquarters in London, it wanted to embed some of the principles of the circular economy into the project, as well as incorporating best practice sustainability features (such as photovoltaics, green walls, etc.).

The NUS works with student unions throughout the UK to educate students about sustainability and it runs several high-impact campaigns aimed at changing behaviour. The theory is that when people are going through a significant change in their lives, such as leaving home to become students, it is a good time to instil new behaviours into them. The NUS wanted to embody sustainability principles into its refurbished building (completed in 2013) to show what was possible.

Jamie Agombar, the Head of Sustainability for NUS, asked the suppliers and manufacturers on the fit-out contract whether they could offer a service instead of selling their products to the NUS. The only manufacturer that came back with an offer was Philips lighting. Philips proposed a model where it provided a lighting service, rather than selling the light fittings – its Pay-per-lux model.

To deliver the service, Philips provided and installed around £120,000 of LED lighting with comprehensive controls throughout, instead of the less efficient T5 (fluorescent) lamps that NUS would have had to install with its original £40,000 budget (see Figure 12.01).

The NUS pays a quarterly rental payment to Philips for the service, with pre-agreed rates that incentivise efficiency. The energy use of the lighting was estimated at the start of the contract and agreed between the NUS and Philips. If the energy use exceeds this figure, then the NUS pays less rent for that quarter.

Figure 12.01: Macadam House, NUS Offices, London, showing Pay-per-lux lighting.

‘As a registered charity we didn’t want to own services like the lighting,’ Agombar said. ‘Our priority was to ensure the lighting performed as required in terms of light levels and energy consumption.’

To ensure efficient performance, Philips has trained the staff in the building and has been fine-tuning the controls systems. The system now works far better than typical lighting systems in buildings, where sensors are often not recalibrated or settings are overridden.

The fact that Philips is providing a service and retains ownership of the equipment makes three contributions towards the circular economy philosophy:

- Philips is responsible for any upgrades and replacements to ensure that it retains its performance and rental income. This should incentivise Philips to design its systems to be easy and cost-effective to upgrade.

- It is responsible for the fate of its equipment at end-of-life, meaning that it should be designed for disassembly, remanufacture or recycling.

- Philips is effectively using the building as a ‘materials bank’ for the future, helping it to secure the source of its components and raw materials in the future. As an added benefit, the energy target incentivises Philips to maintain the lighting to ensure it is performing to its optimum efficiency.

The NUS is now letting out two floors of the building and, as a landlord, is providing the Pay-per-lux as a service to its tenants, in the same way that it provides heating, cooling and ventilation. This opens up the possibility that landlords could provide a lighting service to their tenants or act as a broker for a lighting manufacturer.

Philips has subsequently developed a lamp prototype that can be disassembled and reassembled without any need for tools or adhesives. This could allow the electronic board of the light source to be upgraded or the parts of lamp to be reused or recycled separately.2 This shows that creating new ownership models can incentivise manufacturers to redesign their products for a more circular economy.

Incentivising Return

Selling services instead of products is one way to ensure that building components and contents are returned to the manufacturer for reuse or remanufacture. Another way to close the loop is to incentivise customers to return products when they are no longer required by offering to buy them back or to provide a discount on the next service.

Some organisations have recognised the advantages of ensuring that their products are returned and have set up the infrastructure to collect products, the incentives to ensure a high return rate and remanufacturing capabilities to squeeze the maximum value out of the used products.

Caterpillar manufactures machinery and engines, including construction and mining equipment. It uses its vendor and distribution system to collect used components and operates a deposit and discount system to incentivise their return.3 Customers pay a deposit when they purchase new equipment, which is paid back when they return the product. Caterpillar operates a remanufacturing division that disassembles the products, then cleans and inspects the components to determine what can be salvaged. The components and the ‘core’ of the machinery or engine can then be remanufactured to a very high performance standard, which allows Caterpillar to offer the same warranty for their CAT® Reman engines as for new products.4 This process allows Caterpillar to:

- get valuable feedback on the design of their products

- reduce their materials costs

- provide a reliable source of remanufactured components

- provide a parallel business stream of remanufactured products and

- help to create long-term relationships with their customers.

This business model is starting to be applied to building components and contents, such as furniture.

Rype Office, London

Furniture reuse is a well-established practice in the UK, with networks and organisations offering reclaimed furniture. However, WRAP estimates that only 14% of office desks and chairs are reused every year in the UK with the remainder going to landfill, energy recovery or recycling.5 This equates to around 75,000 tonnes of office furniture going to landfill annually.6

Figure 12.02: Remanufacturing process.

Rype Office draws on circular economy principles to create high quality furniture with less environmental impact, whilst creating local jobs through remanufacturing. Its business model addresses every stage in the life of furniture with the aim of moving beyond the linear model of consumption and disposal. Rype Office helps companies to refresh and resize their existing furniture, remake furniture sourced from elsewhere at half the cost of new and choose new furniture that is easy to remanufacture, giving it a much longer potential lifetime.

It also offers guaranteed buy-back on its furniture and even a leasing service, giving customers the flexibility to return unwanted furniture or to lease more as their organisations change.

According to Dr Greg Lavery, director of Rype Office, the most common reasons for not using remanufactured furniture are concerns about quality and about the volumes that can be supplied.

‘When you put top grade remanufactured furniture alongside new you cannot tell the difference, not even with a magnifying glass – that is how good it is. Modern resurfacing technologies and remanufacturing processes are very high quality. And of course you can choose the colours and finishes that you want because we are completely remaking it,’7 says Greg in response to the first concern.

And in response to the second concern about whether the volume of stock is available, he notes that there are hundreds of thousands of furniture items from office clearances now sitting in warehouses since the global financial crisis, just waiting to be remanufactured.

Rype Office’s remanufacturing model creates:

- remade furniture at half the cost of new

- reduces the environmental footprint of each piece by an estimated 70%

- creates skilled jobs in the UK, and

- reduces the amount of new furniture and components that have to be imported into the UK.

Conclusion

These service models could be extended to encompass the whole fit-out of a building, allowing occupants to lease everything they need from the manufacturer. This could give occupants access to the latest technology or trends and allow them to transfer the risks of trialling these new ideas to the manufacturer, along with the total cost of ownership.

At first glance, leasing models appear more expensive than simply purchasing products outright. However, this can change when the total cost of ownership is considered. Calculating the total cost of ownership involves gathering together a whole range of costs that are not normally associated with the purchase of the equipment. This includes the costs associated with maintenance, premature failure, functional obsolescence, replacement and the storage of surplus equipment or replacement parts. Depending on the leasing models, it could also include the energy costs of mechanical and electrical equipment and the disposal costs of products, including hazardous materials that would require specialist handling.

These business models help to ensure that products and materials are kept in circulation for longer and also offer multiple benefits to manufacturers and customers, if they are set up to the benefit of both parties and the right infrastructure is put in place. Manufacturers can develop longer-term relationships with their customers, whilst reducing their cost of materials and their exposure to volatile materials prices. They can create a second revenue stream and customer base by selling remanufactured products and obtain feedback on their products, allowing them to develop higher-quality, longer-lasting goods. Remanufacturing creates local employment opportunities and reduces the need to import goods. The customers benefit from lower-cost products with the potential to enter into service agreements that mean they are not responsible for the maintenance, upgrade and disposal of products.