CHAPTER 4

How to Find the Right Venture Capital Firm

You've decided you want to invest in venture capital as one component of your overall asset allocation strategy. Now, how do you find which firm to invest with?

Surveying the Landscape of Venture Capital Firms

On the surface, there appear to be lots of options. According to FindTheCompany.com, there are around 1,200 venture capital firms to choose from. That includes some overseas firms as well as many that might be better characterized as angel groups.

While the line between venture capital firms and angel groups isn't always clear, other sources that use a tighter definition of venture capital firms estimate the number of U.S.‐based venture capital firms in the 500–600 range. This excludes angel groups and individual angels, who generally invest even earlier in the evolution of a venture.

Unless you already know a lot about venture capital and also have a lot of time on your hands, we'd suggest you focus on venture capital firms and exclude angel groups from your consideration set. Angel groups generally require considerable time from their members, who typically handle the venture screening, due diligence, and investment administration tasks that are handled for you by professionals at more traditional venture capital firms.

Since this book attracted your attention, we're guessing you do not have extensive venture capital investment experience. If that's right, we'd strongly urge that you look for a firm with solid professional venture capital investment experience and practices. That will leave you with a smaller but still apparently robust number of choices. You'll be surprised to learn, though, that there really aren't as many firms to choose from as it may appear.

As you scan the venture capital horizon, you'll see that venture capital firms come in a broad range of sizes. Total capital held by these VC firms ranges from as little as $10–$20 million all the way to the billions. According to a list of U.S.‐based venture capital firms compiled by WalkerSands Communications, a public relations firm focused on the high‐tech venture and venture capital communities, the largest appears to be New Enterprise Associates in Menlo Park, California, with total capital reported at $11 billion. Next in line is Accel Partners in Palo Alto, California, with total capital reported at $8.8 billion. The WalkerSands list includes 53 firms with total capital of $1 billion+.

The practical reality is that you can scratch all those billion‐dollar‐plus firms off your list of possibilities, because they won't even take your money. Believe it or not, it can be difficult for individual investors to find seasoned, professionally managed venture capital firms that will let them in on the industry's historically strong returns.

Unless you're really wealthy, or extraordinarily well connected, or willing to invest a big portion of your net worth with a single VC firm, you shouldn't even consider the big firms. The minimum commitment for such firms could be in the millions of dollars. These firms' funds are generally limited to big institutional players like pension funds, college endowments, or a fund of funds.

Some of these leading firms may accept a commitment of just $1–$2 million, but unless your net worth is $10 million or more (in which case, congratulations!), we wouldn't recommend investing that much in venture capital. While we love venture capital—it has done very well for Len over the past 30+ years and for Ken over the past few years—we do not recommend investing more than 5% or so of your assets in it unless your assets are in at least that $10 million range or even greater. Since there are only about 1 million households in the United States with net worth of $5 million+ and less than half of those have a net worth of $10 million+, unless you're the proverbial needle in the haystack, even we wouldn't recommend committing $1–$2 million to this asset class, let alone trusting all that to just one fund.

You may have heard that some of these leading institutional firms have a smaller “sidecar fund” for individuals that they establish at the same time as their main fund. The bad news is that access to these specially created ancillary funds is very tight, usually just for the firm's major contacts, previous entrepreneurs, and other important business relationships. Unless you have those kinds of connections—and not many do—you can forget about these major firms.

Once you exclude those behemoths, as well as the do‐it‐yourself angel groups, you'll still need some way to segment the remaining number of choices in order to make your selection process manageable. There are a number of dimensions on which to segment the field. These include the stage in a venture's evolution when they most often invest, venture industry, and venture geography.

To dig through these variables, FindTheCompany.com has the most complete database we're aware of. Their summary list shows firm location, the venture/financing stages on which they focus, and the firm's minimum and maximum investments in any given deal. You can then drill down to a more substantial database at the firm level, showing numbers of deals they've done and the number of companies in their portfolio, specific portfolio companies and their industries, the size of each investment as well as cumulative funds invested, and the scale of their exits and the nature of each exit (e.g., IPO or acquisition). Notwithstanding the extensity of their database, though, it is not complete (nor do we suspect any is), as it doesn't even include our existing and new firms, despite a recent $1 billion+ exit for one of our portfolio companies that received considerable press.

Another helpful list can be found on the industry association's (National Venture Capital Association) website (www.nvca.org). Their website lists nearly 350 member firms and provides links to the website of each individual member firm. Again, this list is incomplete, including only member firms and so leaving out any (like our firms) that are not dues‐paying members.

Let's look at some of the variables you can practically consider in selecting a firm with which to invest.

Firm Selection by Venture Stage Focus

Let's start with the stage in a venture's growth and maturation. Many venture capital firms focus their investments on just one or two venture stages. This strikes us as a good way to begin the sifting‐to‐selection process. Here is a description of the venture maturity and associated investment stages based on stage definitions in the 2015 National Venture Capital Association Yearbook.

Seed Stage

In this stage, a relatively small amount of capital is provided, usually to prove a marketplace/product concept. This stage usually involves market research and product development and then, assuming going‐in hypotheses are borne out, beginning to build a management team and business plan. This is often before any actual marketing has taken place.

The funding for this stage, which typically comes after the entrepreneur has maxed out his or her credit cards and contributions from family and friends, is often sourced from individual angels and angel groups. However, it is also sometimes pursued by professionally managed venture capital firms, particularly firms that may be interested in investing in subsequent financing rounds if venture progress justifies that. This is what we meant when we said the line between venture capital firms and angel groups isn't always clear.

Financings at this stage are generally not more than about $500,000, and usually less, but could occasionally run up to the $1 million range. A presentation by the Angel Capital Association to the SEC in 2013 analyzing available 2012 private venture financings found angel/angel group investments averaging $342,000 per deal, this compared with an average venture capital financing round (across all venture stages) of $7.2 million.

Why would someone invest at such an early stage? Perhaps because it is the ultimate bargain; the venture's share price is inevitably lowest at this stage, so potential gain is greatest. But this stage is really not for the faint‐hearted, as less is known about the venture so early in its development and so uncertainties are greatest at this initial stage.

Early Stage (Post‐Seed)

Think about the process of venture maturation as being like a funnel. While lots of ambitious entrepreneurs set out to create the next Microsoft or Facebook, a large majority fall off the rails over time. The majority of the seed stage ventures will never even reach this post‐seed early stage. Perhaps the hypotheses that motivated the venture will be invalidated, or it will appear likely to prospective investors (and maybe even to the founding entrepreneur) that success odds and return potential just aren't great enough to risk further investment.

For those ventures that pass this screening stage, their share prices will be higher than at the seed stage. Risks and uncertainties, while still great, will have diminished some. The probability of a positive return, while still pretty low, will be greater than before.

Financing needs at this stage are usually greater than at the seed stage, typically in the $0.5–$5 million range. This is where venture capital firms usually take over from the angels. At this stage, the venture generally is approaching product development completion and is focused on market testing or pilot production, with product refinement often still ongoing. While possibly still fleshing out its organizational structure, the company is often already selling in the marketplace on a limited scale.

This limited scale is usually too small to be profitable. While a venture might even be capable of operating profitably on such a limited scale, successful venture capital investors don't go after ventures for the limited profits associated with limited scale. Their objective is to invest in businesses with substantial growth potential that justifies continued aggressive investment, often to fund market testing in order to determine the optimal formula for eventual profit maximization. Continued enterprise losses at this stage usually are not a big concern. In addition, in some fields, such as in the medical area, where extensive testing and government approvals are required before any marketing can be done, the venture may still be far short of selling in the marketplace.

Expansion Stage

The winnowing down continues, and those ventures that reach what is called the expansion stage will have passed another critical stage gate. While ultimate marketplace success may still be uncertain, the odds are getting better. And the share price is usually increasing as well.

At this stage, the venture usually is being actively sold in the marketplace. The venture may already be profitable, but require substantial funds for rapidly growing receivables, inventories, and perhaps increased production capacity as well. Alternatively, the venture may still be operating at a loss while investing aggressively in envisioned substantial long‐term growth. Risks are likely still great enough that a conventional lender like a bank is generally not viable.

The dollar magnitude of financing rounds continues to increase at this stage, typically to the $5–$25 million range. Some venture capital firms focus most of their dollars on this or even later financing stages. The larger the financing round, the more likely the money will come primarily from institutional investors and the less access individuals will have.

Firms still working primarily with individual investors may, however, participate as well at this stage, sometimes in support of ventures they funded earlier and that still hold attractive promise. (If the potential of a venture they funded earlier no longer seems as attractive, the firm's focus will instead be on recouping as much cash as they can—and that may be zero—limiting losses and moving on to greener pastures.)

Late Stage

At this point, the likelihood of marketplace sustainability is greater, even if ultimate growth potential is still uncertain. This is where the dollars sought for investment get really large, sometimes even in the hundreds of millions of dollars, as the business may need substantial investment capital for rapid growth and timely market domination.

At this stage, the venture may already be large and sometimes even well known, but its owners believe its value will be still greater as it more closely approaches longer term potential. Think about companies like Uber, Airbnb, and others that have already become household names but that still seek further investment to realize their full potential.

Share price is usually considerably higher at this point, as the risk of total failure and total loss is considerably less. Participation at this stage is generally limited to the major institutional venture capital firms catering primarily to institutional investors with the capacity to meet the much greater investment need.

Historically ventures had exited from the venture capital realm by this stage and pursued an initial public offering (IPO). However, in more recent times, given all the pressure public companies are under to report earnings progress quarter‐after‐quarter, some of these high potential ventures and their venture capital shareholders have chosen to remain private somewhat longer in their quest to minimize such pressures and focus on maximizing long‐term gain. Of course, some of these unicorns (privately owned ventures valued at $1 billion+) may instead simply fear the reception they anticipate from the public market, which might result in a big fall in share value for its expansion‐ and late‐stage venture capital investors.

Why Should You Care About a Firm's Venture Stage Focus?

So why should you care so much about the venture stage where a firm is focused? You might want to target your investment dollars at the seed or early stages, where there are fewer investors involved, because you want to have a personal influence on the direction of the company. Or perhaps you are inspired by the venture's mission, and hope your early investment not only makes you a healthy return but also makes a real difference to the world. Maybe you've lost a loved one to a particular disease and want to invest in a potential cure, and so you're ready to commit dollars as soon as there seems to be a reasonable opportunity. Or maybe you have always wanted to create a world‐changing venture and see your investment dollars as a way to contribute to such a development.

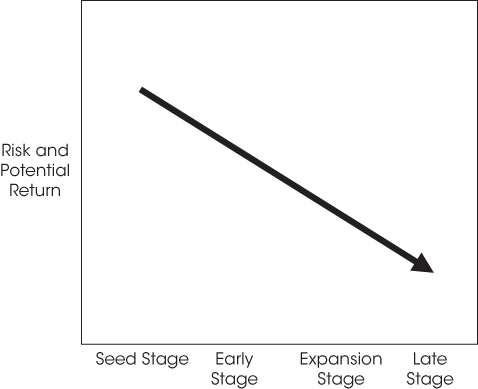

From a financial standpoint, as we've discussed, investment at different stages carries different degrees of risk and associated potential gain. Quite simply, generally the earlier the venture/financing stage, the lower the share price, so the greater is the return potential, but the greater as well is the risk of total loss. (See Figure 4.1.)

Figure 4.1 Risk/Reward Tradeoff by Stage

There are ways, though, of managing the greater risk of earlier‐stage investment. One is through a firm's more insightful screening and rigorous vetting of its investment candidates in order to do a better job of deal selection. Another way is through your own investment diversification—just invest in more seed and/or early stage ventures to hedge your bets, as some percentage are likely to strike pay‐dirt. We'll get more into thoughts on managing diversification later.

The firms Len has run have focused strategically on early stage investment, but generally not at the seed stage. While leaving seed investment to others may cause us to miss out on the very greatest return potential, it enables us to know more about the venture before investing. We thereby can better assess a venture's potential and success odds, leading to a higher batting average.

We believe one of our competitive strengths is rigorous deal screening and due diligence—superior deal selection—which requires the greater analytic opportunity that wouldn't be possible at the seed stage. While we do sometimes participate in later expansion‐stage investments, when we believe strongly in a venture's potential and likelihood of success and also want to meet our investors' desire to increase their commitment, the higher share price as a venture matures also reduces the potential multiple we could ultimately realize on the investment.

Firm Selection by Industry Focus

Some venture capital firms differentiate themselves based on the industries in which they invest. They may invest in some predetermined range of strategic industries or perhaps even focus in just one or two. Some industries typically chosen for focus include information technology, telecommunications, mobile applications, big data, and biotechnology, to name just a few—industries where there's lots of market‐changing innovation.

Some investors select a venture capital firm based on its focal industries. Perhaps an individual believes strongly in the growth potential of certain industries and therefore wants to focus her venture capital dollars in those industries. Or perhaps an individual is particularly knowledgeable about an industry. That person might then have a greater interest as well as possibly better ability to select specific venture capital deals in that industry. Or an individual may choose to invest based on some personal mission. A person who lost a loved one to cancer might be motivated to invest with venture capital firms focused on biomedical ventures and go on from there to invest specifically in their deals focused on cancer treatment.

While most venture capital firms tend to focus on high tech, regardless of the specific industry or technology, that's not the case for all. For instance, there are firms that invest specifically in consumer products, services, and retailing ventures.

One of our most illustrious business school classmates, Tom Stemberg, who earlier in his career founded office super store pioneer Staples, spent the final years of his career, before his tragic, untimely death, heading up a venture capital firm focused specifically on consumer products, services, and retailing ventures. While some of those ventures have admittedly been highly innovative and strategically astute, most have also been far from high tech. If you're a consumer products heavyweight, you might choose to invest with such a firm to take advantage of your experience, knowledge, and interest.

As Len has done with his previous funds, our current firm, VCapital, is focused on high tech and hard science. Specific industry sectors include mobile digital products and services, cloud computing and big data, media and telecom, biotechnology, medical devices, and biomedical and drug discovery. These broad sectors have the potential to produce and capitalize on disruptive technologies, reach a large and addressable market, and provide significant commercial opportunities.

These are also sectors our team knows and understands. They are consistent with Len's previous funds, which invested in and influenced such winners as America Online (known more broadly now as AOL), Atlantic America Cablevision, Illinois Superconductor (now called ISCO International), Nanophase Technologies Corporation, CyberSource, and Cleversafe. For younger readers, AOL was the pioneer in bringing Internet connectivity into people's homes. As discussed earlier, Cleversafe, which has pioneered tremendous innovation in data storage, is the only company on this brief list that did not exit via IPO; it was instead acquired by IBM in late 2015 for over $1 billion. AOL and CyberSource also grew into enterprises valued at over $1 billion. In fact, at its peak, AOL was valued at $364 billion.

As you consider venture capital firm options, keep in mind that they are not one‐person operations. Our VCapital team includes seasoned executives from industry sectors we focus on, to guide in our assessment of ventures in our targeted industries.

Firm Selection Based on Geographic Focus

Some firms focus their investment activity in particular geographic regions. That's not as surprising as it might sound. Venture capital management is a labor‐intensive endeavor. A VC may review hundreds of deal opportunities in order to find a small number to really zero in on for the most rigorous vetting. Vetting those finalists may require extensive observation of their operations and management teams. There's sometimes no substitute for onsite observation in such analysis. Geographic proximity makes that much easier and more efficient.

Similarly, once the venture capital firm has pulled the trigger and invested, its principals will want to remain in close contact with the venture management team. That's needed to keep informed, to provide consultative help, and in some cases to intervene in order to protect the firm's investment. Geographic proximity can help make all that more manageable.

Many venture capital firms focus on popular hotbeds of high‐tech innovation. Silicon Valley (i.e., the San Francisco and San Jose metro areas) is at the top of that list. Other hotspots include the Route 128 circle around Boston and the Austin, Texas metro area. These areas benefit from a professional infrastructure that encourages and supports startups. However, they also can foster an investor frenzy, with too many dollars chasing available deals, resulting in early share prices too high for many investors' liking.

Len's firms' geographic focus through most of his career, including currently with VCapital, has been the Midwest, far away from the Silicon Valley herd, with Chicago as its bullseye. We won't pass up great deals from other regions, including Silicon Valley, but we believe the Midwest represents exceptional opportunity.

The region's outstanding universities and diverse industries create a wealth of intellectual capital—the seeds of venture capital. Yet the region's history and culture mean less investor competition for the best deals, resulting in better deal values and therefore superior investor return potential. Moreover, the extensive and diverse industrial environment can facilitate venture exits through corporate acquisition rather than having to wait for an IPO, which can mean more reliable and timely return on venture capital investment. This thinking is captured graphically in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 Why the Midwest?

Sources: Forbes; DriveCapital.com

Len's team's track record speaks to the wisdom of this Midwest focus. Most of our big winners have been Midwest‐based. Our latest home run, Cleversafe, is Chicago‐based, as is our VCapital firm. Nanophase Technologies and ISCO International are also Illinois‐based.

The Chicago metro area in particular is the go‐to destination for the region's top university graduates and entrepreneurs. Latest venture capital results from this third largest city in America are impressive—2015 startup funding of $1.7 billion and about 40 exits generating $8.2 billion for their investors. In fact, according to data from PitchBook, a Seattle‐based research firm, over the past ten years, among ventures that have exited, 45% of Chicago‐based venture deals that raised at least $500k produced returns of more than 10‐fold, a greater rate of home runs than any other U.S. city, and 81% of Chicago exits generated investor returns of at least 3×, again higher than any other U.S. city. (Source: John Pletz, Crain's Chicago Business.)

The New Online Equity Crowdfunders

You may have heard of and be wondering about the new online equity crowdfunding firms, such as FundersClub, CircleUp, SeedInvest, or AngelList, to name just a few. They may seem ideal to novice venture capital investors due to their low minimum investment requirements—often just $3,000–$5,000 and sometimes even as low as $1,000.

We urge caution. The backgrounds of the management of some of these firms appear to be more in information technology than in venture capital, and these firms are so new that the jury is still out on their investment acumen. Most VC‐funded ventures take 5–10 years to exit, so it's just too early to assess their investment results.

We hesitate to denigrate the competition. We VCs do try to operate as a symbiotic ecosystem, frequently partnering with other firms in investment syndicates to best meet the needs of investors and entrepreneurs. However, when we look at all the resources some of these equity crowdfunders have devoted to fundraising and to their website technology platforms, they seem more like Internet plays than professional venture capital firms.

Our concern with these new online equity crowdfunders is compounded by their vast portfolios of deals. They typically offer dozens and sometimes even 100 or more deals. They look almost like venture capital flea markets. While they surely practice some analytical rigor in their deal selection, we don't see how they can screen and vet all those investment options with nearly the rigor practiced by more traditional professional venture capitalists.

Admittedly, as members of a seasoned, professional venture capital firm, we're biased. Conceding that bias, let's come back to what should be our readers' highest priority need—seasoned, professional investment management to maximize the likelihood of the robust returns that attracted you to considering venture capital in the first place.

Again, it's too soon to know if the new equity crowdfunders will measure up on that criterion. Our guess is that the best these firms, with their extensive portfolios, will be able to achieve is to come close to delivering industry‐average returns. We'd even venture (no pun intended) a step further and forecast that these crowdfunders will do less well than the industry averages, because we don't see how they can perform as well as the universe of professionally managed, more discriminating firms.

While our new firm, VCapital, offers an online investment portal as well, it is not a crowdfunding site like these just‐mentioned firms. Our technology platform has been kept pretty simple and straightforward and our fundraising resources pretty basic. We offer an online investment portal because today's individual investors expect and demand its accessibility, convenience, and transparency.

Our $25,000 minimum investment requirement, though, means we don't need thousands of investors like the crowdfunders. We therefore don't need the technology and fundraising resources required by the crowdfunders. Our target is more discerning individual accredited investors. Our resources can therefore be devoted more to professional investment management and subsequent engagement with our portfolio ventures, to best address our investors' primary objective, outstanding returns. While VCapital, too, is a new firm, its team has a long track record with its predecessor firms. Our professional investment management bona fides are proven.

To be clear, we are not alone. There are other highly qualified, professionally managed venture capital firms as well. Our point is that these are the sorts of firms we'd recommend that you look for.

Other Resources for Selecting a Venture Capital Firm

In addition to the largely do‐it‐yourself online approach discussed thus far, another good source for finding the right venture capital firm for you might be through recommendations from relevant experts. These might include:

- Attorneys, especially those involved in VC/entrepreneur deal‐making

- Accountants, particularly those with clients who are substantial investors or those involved extensively with businesses in their startup or early stage

- Entrepreneurs who have ever secured, sought out, or considered seeking venture capital funding

Regardless of what side of the relationship these experts may have been on—for example, attorneys representing either the VC or the entrepreneur seeking funding—their exposure should give them some feel for which firms might suit your investment needs and preferences and your investor personality.

Vetting Venture Capital Firm Candidates

You've narrowed down your search to a short list of venture capital firm candidates with whom you are considering entrusting your hard‐earned investment dollars. How do you further assess those candidates and make a choice?

We'd suggest you first go to the firms' websites. Consider what you see. You'll get a sense for the way they think about their mission and about investing your money. You'll see where they focus from an industry standpoint. You'll likely see what's in their existing portfolio and probably hear about their successes.

Hopefully the websites will give you a feel for each candidate firm's team. Is the team filled with marketing and IT‐type people? That could be a warning sign, suggesting they are focused even more on raising money than on investing most wisely for you. Or do you see a heavy dose of investment professionals and experts who are dedicated to making the best investment selections and who could then help the firm's portfolio companies?

There are often photos that at least suggest something about key people's demographics. Do the team members look really young, so they may know technology well but may be less likely to have the investing and consulting experience that could be vital? Or do you see team member maturity that will more likely have the business and investment experience that may be more important? Photo settings and attire may also tell you a little about the firm's personality. Are they conveying any particular image that may be relevant to understanding their approach?

The resources included on their websites, such as blog posts, podcasts, or links to articles, may tell you something about what's important to the key people on the team. Are they stressing investor education (maybe a good fit for a novice venture capital investor)? Or might they be stressing their vision regarding future marketplace trends and anticipated investment opportunities (also maybe a positive sign)?

Unfortunately, what you won't find on some firms' websites is any clear articulation of how well they've done. They may talk about some big exits. The website FindTheCompany.com actually does an extensive job of detailing how much has been invested and even showing the scale of exits since 2003.

But it's tough to find the kinds of numbers you'd really like to see, especially a firm's realized average annual return or internal rate of return for an extended period (i.e., the returns they've actually delivered based on deal exits). You may see numbers touting tremendous growth in the value of their investments. Keep in mind, though, that these valuations mean little until there's an exit and you collect your share of the cash.

Given the long‐term nature of venture capital investments, securing realized returns data for existing funds is understandably difficult. The next best data is the realized returns the firm or investment team has delivered through its previous funds. Notwithstanding the disclaimer, “Past results are no guarantee of future performance,” which you so often hear from financial services firms, that past performance may indeed be the best indication you can get of future results in this industry.

Those hard historical measures may sometimes be difficult to get ahold of. In fairness to other VCs, some are concerned with the legal and regulatory risks around communicating such hard numbers. They may fear that such communication can leave them open to legal issues should others not agree, for example, with their methodology for calculating those numbers.

We have faced that same challenge in presenting our team's new firm, VCapital, though we have decided that such performance track record reporting is too important to leave out. We have therefore gone to great lengths to detail historical results deal‐by‐deal, showing the losers as well as the winners, to ensure supportability and credibility.

Many firms are reluctant to disclose all those details, especially because of the industry's typical 80–85% deal failure rate. Hence, you may need to communicate privately with your venture capital firm candidates and probe aggressively for such hard numbers. They may share with you privately data details that they do not feel comfortable promoting publicly.

If you do that, don't let them fool you with measures that include current valuations for ventures that have not yet exited. Some of our more marketing‐aggressive fraternity may try to sell you with such measures. For example, anyone who invested in Uber some time ago might want to include in their calculations the current value of that earlier investment based on Uber's latest $66 billion valuation. But until an exit actually happens, or the firm in question has already sold its shares, that $66 billion valuation doesn't mean too much. It could still be driven down by many factors, for example, more market retreats like in China, where Uber recently withdrew; more municipalities that either push Uber out or simply bestow greater advantages on their licensed cab fleets, as is happening right now in London; or adverse legal rulings regarding the relationship between Uber and its drivers that could significantly change the company's economic model. So be sure you know what the numbers they show you really mean.