9

IGNITING THE ENGINE

CREATING A GOVERNANCE AND COORDINATION STRUCTURE FOR THE INNOVATING ENGINE

If you were playing a word association game, the top response to “Bayer” would be inevitable—“aspirin.” The 150-year-old company is best known for its development and marketing of acetylsalicylic acid, the miracle drug developed by Bayer chemists in the 1890s and originally trademarked worldwide as aspirin. But though aspirin is still a mainstay of Bayer’s business, the $40 billion company also profits from a steady stream of innovations in pharmacology and the life sciences: for example, technologies that help smallholder farmers in developing countries expand their production of sustainable crops; artificial intelligence (AI) software designed to improve clinical decision-making regarding chronic conditions like hypertension; and breakthrough treatments for medical conditions ranging from hemophilia to prostate cancer. These examples reflect just a few recent months of Bayer research.

Breakthroughs like these reflect the degree to which Bayer recognizes the centrality of innovation to its future success. The company operates according to a mantra that was explained to me by Dr. Henning Trill, one of Bayer’s innovating leaders and head of Corporate Innovation: “When running a sustainable business, innovation and marketing are critical. They cannot be outsourced and they can’t be delegated to others. Even though innovation often calls for cooperation and partnership with outside stakeholders, such as business partners, academic research organizations, biotech companies, medical institutions, and many kinds of customers, the innovating process itself must be driven from within—because otherwise, the company runs the risk of losing control of its destiny.”

Of course, Bayer’s stream of business-building innovations depends fundamentally on the ideas generated by scientists, engineers, and researchers in dozens of Bayer laboratories around the world, as well as other technical experts in companies that partner with Bayer. But ideas are just the beginning. In the words of Dr. Monika Lessl, Bayer’s head of Corporate Innovation, R&D and Social Innovation, who leads the organization’s innovation efforts: “Ideas are cheap! We’ve learned creation is not enough. . . . The idea is critical, but the translation to bring it to life and our understanding of the underlying problem is where we often fail. We often love our solutions or technologies and don’t invest enough time and energy to search for the real customer or patient need. That’s why innovation leadership is different from other kinds of leadership. The first is both a product of a purposely created environment and the cause to make ideas happen.”

The “purposely created environment” that Bayer has developed to keep “making ideas happen” adds up to a powerful—and thoughtfully designed—innovating engine.1

How Bayer Encourages Innovators: WeSolve and Beyond

As Bayer’s 150-year track record suggests, the company has been innovating for a long time. But as the world evolves, so must business methods and strategies, and this applies to innovating as much as to other practices. Bayer’s contemporary journey of innovating began with what Monika Lessl calls “a white sheet of paper” in 2014, when the company realized it needed to provide its many widely dispersed worldwide employees with better ways to innovate—faster, more agile, more open-ended. “We had a hundred thousand people around the world, all wondering, ‘How can I contribute to innovation?’” says Dr. Lessl. “This resource offered us immense potential. We asked ourselves, ‘How can we leverage it?’”

One crucial piece of the answer related to Bayer’s corporate structure. Bayer is a huge company, with employees in three major business divisions (pharmaceuticals, consumer health, and crop science) scattered across 36 country groups around the world. Inevitably, such a company must be organized along hierarchical lines, with the bureaucratic systems and procedures needed to maintain control and strategic focus while engaging in hundreds of thousands of separate activities. Yet bureaucracy can easily become a deadening influence that stifles innovation.

Dr. Lessl and her team were inspired by the organizational model of John Kotter, well-known management theorist. He has spoken and written extensively about how organizations can develop dual systems that combine traditional vertical hierarchies with more flexible, horizontally structured networks in order to facilitate freewheeling interaction, communication, and collaboration. They decided they needed to find a way to create such a dual structure in support of their employees’ innovating efforts.

Notice that the duality Kotter and others have recommended is closely related to the concept of the two engines that I’ve presented in this book. The hierarchical structure most big companies have inherited from their history is strongly aligned with the execution engine that performs crucial daily functions. The horizontal network needed to open up channels of communications among people in various functions and departments is aligned with the innovating engine that fosters creativity. The question is, How to operate both engines simultaneously, and not as separate units with different personnel but with the involvement and support of everyone in the organization?

During a strategy project in 2015, the innovation team led by Dr. Lessl decided to develop a horizontal network dedicated to innovating that would invite the creative participation of everyone in the company. Then the company would find ways to feed the ideas fostered by this network back into the hierarchical execution system.

In creating such a network, managers would play a crucial role. Dr. Trill explains why:

When we started the Innovation Agenda, I thought I could spur innovation by asking the company’s senior leaders to name their three biggest problems. Then I would turn to Bayer people at all levels to find solutions. But that didn’t work. The questions asked were too big and needed a further breakdown to be solvable. We had to systematically reach out to the organization via the Innovation Network to identify the right type of challenges that would trigger new solutions and even business models.

The people in the country organizations are much closer to the challenges of the customers. They were essential to finding issues like, “Farmers in Spain want a way to monitor the pesticide levels in their crops at harvest time, and, even better, a way to predict those levels so they adjust their planting methods accordingly.” The local managers and frontline employees are the people who are in touch with customers and aware of their needs, issues, concerns, and wants. And they are the people who are not only willing to use creative problem-solving tools to innovate solutions but to actually experiment with those solutions until they find something that really adds value to the customer and for which the customer is willing to pay.

Originally the process of unearthing the countless challenges that Bayer people needed to address started with the launch of an online idea forum called WeSolve. This is a digital platform where Bayer employees from around the world are invited to post challenges, problems, and opportunities that they recognize from their local businesses. Other employees who visit the forum can then propose ideas for solutions. It’s a kind of internal crowdsourcing tool that lets Bayer people from everywhere meet with one another in virtual space, bringing their unique experiences, knowledge, and insights to bear on far-flung issues they’d otherwise never hear about.

WeSolve quickly became a popular visiting place for Bayer employees. Within a year of its creation, more than 23,000 of Bayer’s 100,000+ team members had visited the forum, and some 1,650 had contributed either challenges or possible solutions. Over time, fascinating and valuable new uses were developed for the forum. Not only technical or scientific solutions were sought. When Bayer’s human resources division developed a new performance appraisal system, WeSolve was used as a platform for soliciting feedback from many of the company’s most engaged and thoughtful employees. When volunteers were needed to serve as early testers for new Bayer products or services, WeSolve turned out to be an effective way of recruiting them. When product marketers needed feedback on their plans from people who represent the potential customer base (arthritis sufferers, for example) they discovered they could turn to WeSolve to find such people among Bayer’s worldwide employee base. When Bayer seeks an outside partner—another company, a nonprofit organization, or an academic institution—to provide the specialized skills or tools required to support a nascent project, WeSolve participants are invited to contribute suggestions and connections.

Additional innovation forums have also been created with specialized mandates. Some of these invite users to post ideas or solutions rather than challenges. One of these is called WeIdeate, a subforum within WeSolve. This forum focuses on specific activity areas or local problems. This is a deliberate strategy. Bayer has found that posting ideas works best within a small universe of people who share common issues and concerns. Outside this sort of limited setting, it is much less useful. As Dr. Trill observes, “Posting ideas in a broad-based online forum usually leads nowhere because there’s not much chance that the person who owns the underlying problem will see the idea and then jump to adopt it. In a general-interest forum, it’s much more effective to post challenges because then the potential solutions that people post in response have a built-in constituency.”

Of all the Bayer forums dedicated to innovating, WeSolve has proved to be the one with the greatest impact and staying power. As of fall 2020, more than 40,000 Bayer people have participated on WeSolve. Considering that WeSolve is entirely in English, and only about 50,000 of Bayer’s employees speak English, that’s a very impressive rate of engagement.

More than 200 problem-solving challenges are now being posted on the forum every year. When I visited the WeSolve forum in mid-2020, I was impressed by the number and variety of issues it featured, all raised by Bayer employees for potential solution by others. Some posed problems that were quite technical: “We are looking for an additional safety measure to improve our dust-free big bag filling process.” “Looking for ideas for improving germination rate and consistency across a variety of weed seeds.” “We are looking for a suitable genome/variant graph algorithm for crops.” Others were almost philosophical or even playful—for example, a survey on the topic “Is transparency in what you eat important to you?” and another asking for creative suggestions for a brand name for a new product for the Indian market. Scanning the dozens of challenges posed, I got the feeling that contributing to the WeSolve forum would actually be fun for Bayer employees. This is probably one of the main reasons the participation rate is so high.

Perhaps most impressive, the average number of visitors to any challenge or request appearing on the forum is about 200. Post a problem on WeSolve, and the odds of attracting a smart solution are quite high. Dr. Trill estimates that about 50 percent of WeSolve problems get solved outright, while in another 30 percent of cases a fresh idea or insight pointing toward a “work-around” is generated. And many of the best ideas come from unexpected sources. Dr. Trill reports that two-thirds of the best solutions come from people in a division or functional area different from the one where the person raising the issue works, reinforcing the value of WeSolve as a tool for companywide intelligence sharing.

Bayer’s Dr. Julia Hitzbleck says, “Often, challenges we post are not solved by someone from that department or function, but from someone in a totally different division. It has really helped us to tap into our knowledge pool, and get into the spirit of working together rather than experts sticking to their own area.”2

Dr. Trill points out another benefit of WeSolve’s broad appeal: “When new employees join Bayer, whether as individuals or as part of a company acquisition, they find that WeSolve is a great way to discover what is happening throughout the business. Reading about challenges faced by Bayer people around the world and even being able to participate in solving them helps to glue the organization together.” The fact that Bayer is being “glued together” around innovating makes it all doubly powerful and beneficial.

The Corporate I-Team: Spark Plug of Innovating

Encouraged by the success of the WeSolve forum, Dr. Lessl and her team decided to spread their new way of innovating to Bayer employees across the organization. To make this happen, they began to build a network of coaches that would play a crucial role.

Throughout this book, I’ve stressed the fact that every employee in an organization has a role to play in innovating. It’s important to break away from the traditional belief that innovation is the province only of a handful of creative geniuses with special talents and a unique role in the organization. The existence of the thriving WeSolve forum certainly sends a clear message to Bayer people that everyone is encouraged to contribute to creating the company’s future.

However, it’s also very helpful for an organization to have a cadre of employees who play special roles in encouraging and maintaining the flow of innovations through all three processes—creation, integration, and reframing. In particular, I recommend creating three new jobs to be assigned on either a full-time or part-time basis to particular members of your organizational team—the innovating coach (or I-Coach), the innovating coordinator (I-Coordinator), and the innovating committee (I-Committee). These three sets of individuals play important roles in reinforcing the culture of innovating in your organization.

Taken together, all the people who fill these jobs make up what I call the innovating team, or I-Team for short. Bayer offers a great example of how to build an I-Team and use it effectively to stimulate innovating throughout the organization.

Note that most members of your I-Team, like other members of your organization, will play differing roles at different times, depending on whether they are operating as part of the execution engine or as part of the innovating engine.

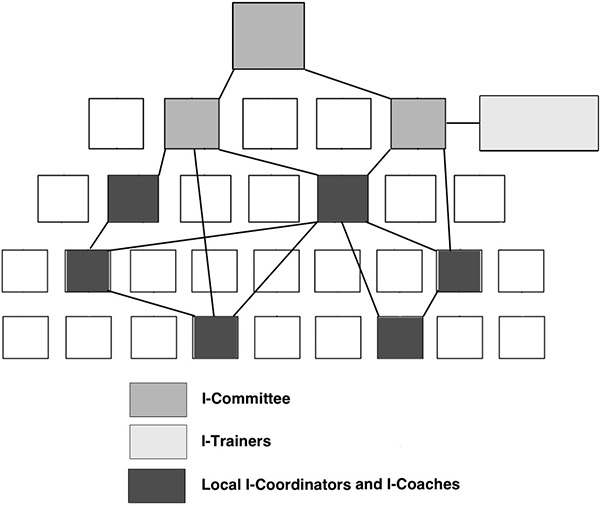

Figure 9.1 illustrates the similarities and differences between the twin engines and their organizational structures. Figure 9.1A depicts, in simplified form, a typical hierarchical structure like the one that most organizations use to govern their execution engine. Connections among the individuals in the chart are depicted by horizontal and vertical lines.

FIGURE 9.1A Hierarchical Roles Within the Execution Engine

In Figure 9.1B, the formal structure of the organization’s innovating engine is depicted. In this figure, the same individuals are shown, with the exception of a new box on the top righthand side of the chart. This box represents a special unit of I-Trainers who work with the I-Committee and train people throughout the organization in innovating methods, in particular the I-Coaches. The I-Trainers also serve as a central intelligence unit that prospects for, evaluates, and selects novel innovation methodologies and techniques as they emerge in the external market. They may also develop proprietary, customized processes for use by those within the organization who seek to innovate.

FIGURE 9.1B Nonhierarchical Roles and Connections Within the Innovating Engine

The other members of the I-Team—including the members of the I-Committee, the I-Coordinators, and the I-Coaches—are embedded throughout the organization at various levels and represented by boxes in differing shades of gray. Also notice the diagonal lines used to connect these I-Team members, reflecting the kind of cross-functional, multi-level teamwork that is characteristic of activities within an innovating engine. As the figure suggests, these connections may be quite different from the ones that exist within the traditional hierarchy that generally characterizes the execution engine.

Of course, every company will adapt the design of its I-Team to fit its culture, size, divisional structure, and other characteristics. Bayer, for example, started by giving an individual member of Bayer’s executive board (i.e., its board of directors) a special responsibility for encouraging and supporting innovating. This was Kemal Malik. He set up a group under Dr. Lessl’s leadership to develop an innovation strategy and define measures for implementation.

A key element of the strategy was to set up a cross-divisional innovation committee of senior executives. Furthermore, covering all country groups and global functions, 80 senior managers were selected to play the role of I-Coordinators, bearing the Bayer-specific designation “innovation ambassadors.”

Finally, a third group of specialists was created, even bigger than the first two. At Bayer, these were called innovation coaches; I refer to them as I-Coaches. Between 2016 and 2020, more than 1,000 innovation coaches were trained, of which about 600 are still at work in Bayer facilities around the world. About 200 additional employees eager to join the team have placed their names on a waiting list.

I-Coaches are individuals trained and certified by the I-Trainers after participating in a corporatewide specific training program that may involve physical classes, virtual training sessions, or a combination of both. Through the training, they learn to use creative methods and tools like those I’ve mentioned throughout this book (and which I’ll discuss in some detail in Chapter 10). Additional innovating methods that the I-Trainers have developed or adopted may also be included in the innovating curriculum. At Bayer, for example, I-Coaches take part in a three-day onboarding program that includes the detailed study of a technique called Systematic Inventive Thinking®, which they often use with their colleagues as a way of stimulating and organizing their innovating activities.

The I-Coach also works with innovating project teams or individual innovators in a particular part of the organization, helping them to understand how to apply the tools most effectively, troubleshooting their innovation efforts and linking them to other innovation-related support mechanisms at Bayer in order to help them make innovating a regular and productive part of their work.

One of the most effective activities sponsored by Bayer’s I-Coaches is what the company calls fast sessions—short workshops with teams of four to six participants designed to address a specific problem, such as the need to simplify an overly complex process or to meet a competitor’s challenge. These workshops have become very popular as they are easy to set up and fun to do.

In addition to fast sessions, the I-Coaches organize and lead one- to three-hour cocreation workshops, which often include individuals from outside organizations, such as business partners or Bayer customers. I-Coaches also hold informal “lunch and learn” gatherings at which innovative ideas from various companies and industries are presented and discussed. Through these cross-functional, sometimes interorganizational meetings, the I-Coaches are helping to support the integrating process discussed in Chapter 5, making connections among individual innovators who otherwise would be unlikely to meet or work together. As Julia Hitzbleck, who built up the Ambassador Network, puts it, “Accounting, procurement, sales . . . they all have different needs, but we want them to have a common language.” Under the leadership of the I-Coaches, “they build road maps, run innovation workshops, engage their local colleagues, and make sure things are actually happening.”3

Bayer’s twenty-first-century drive to encourage innovation at all levels of the company has featured other activities to promote and publicize creative thinking. These include Innovation Days and coworking events at which new business concepts have been presented at Bayer facilities in locations from Shanghai and Tokyo to Boston and Berlin. But on a day-to-day basis, the work of the I-Coaches has played the biggest role in spreading the culture of innovating into every corner of Bayer.

Every company will design the structure and activities of its I-Team to suit its own corporate culture, needs, and innovation objectives. At Sabancı Holding, for example, Burak Turgut Orhun, head of strategy and business development, has created a system for recruiting employees to become members of what he calls X-teams, which are in charge of leading special high-profile, groupwide innovating projects. Each X-team includes workers from different companies within the group, who are selected with the help of human resources specialists. An X-team is typically assigned one highly promising innovating idea, which it shepherds through a development process known as the Innovation Funnel, a task that normally lasts about three months. Orhun has found that the employees who make the best candidates for X-team roles are those with highly flexible, open-minded attitudes—people he likes to refer to as “misfits” or “pirates.” It’s a job that has become highly prized within the Sabancı group; in fact, employees who have formerly served as members of an X-team often proudly mention it soon after meeting a new colleague.4

In 2019, Fiskars, the Finnish company whose innovating methods we explored in Chapter 5, created a new centralized innovating unit named Bruk (the original name of the village where Fiskars was founded in 1649). “If the R&D team at Fiskars is the innovation hub for physical products,” says Tomas Granlund, the leader of Bruk, “then Bruk is the innovation hub for disruptive innovations of other kinds, especially when it comes to digital services and business model innovation.”5 Bruk invites ideas from both external partners and Fiskars’ employees in any department. It periodically launches “business challenges” around specific themes such as sustainability with the goal of quickly designing prototypes for testing and further development. In short, Bruk is a specialized I-Team unit built to meet a specific need within Fiskars’ innovating engine.

I-Coaches as Trainers and Teachers

At Bayer, the I-Coaches help to train their colleagues in using innovating methods and tools. Since 2016, Bayer has trained more than 1,000 employees in innovation methods such as Systematic Inventive Thinking, Design Thinking, and Lean Startup.

The Lean Startup methodology, associated with the work of Eric Ries, entrepreneur, venture advisor, and author, has proven to be particularly valuable. With its wise mantra of “Fall in love with your problem, not your solution,” it encourages continual, open-minded rethinking of any innovative idea. Lean Startup also emphasizes the importance of objective experimentation and testing before any new idea is deemed ready for widespread adoption.

Bayer has taken this philosophy to heart. Dr. Lessl told me about a typical example of how fast prototyping and repeated experiments are being used to test and refine product and service ideas in today’s Bayer. One of the important market segments Bayer seeks to serve in India is the vast number of smallholder farmers, who manage tiny plots of land but who raise, in the aggregate, a large percentage of the food that supports this huge, sprawling country. These smallholder farmers, who play such an important role in supporting India’s food security, could benefit greatly from the products, tools, and information that Bayer’s crop science division could offer them—but bringing these goods to millions of farmers in thousands of remote villages is a huge challenge.

In response, as part of the CATALYST program, a local Bayer team came up with an idea for a chatbot that could connect with Indian farmers through the cell phones that nearly all of them now own. But rather than simply designing such a bot and putting it on the market, the Bayer team wisely chose to start by applying the Lean Startup methodology of repeated testing and experimentation. First they did a series of interviews with smallholder farmers, individually and in groups, to discuss the kinds of services and information they would like to have access to. Based on this input, the Bayer team drew up 10 different proposals for chatbot services, outlining the kinds of contents to be provided and the cost. They presented these options to a cross section of farmers, asking them, “Which of these services would you buy, and why?” They even set up a temporary website where farmers could pick a chatbot option and fill out a registration form to show their interest.

Only after all that preliminary testing did the Bayer team put together a product prototype that embodied all the features the farmers whom they’d studied found most attractive and valuable. When they made the prototype available on WhatsApp and sent a link to 70 farmers for a final test, they discovered that all their previous experimentation had paid off. Not only did their test group react enthusiastically to the prototype, they passed the word about it on to their friends and relations. In response to the 70 offers the Bayer team sent out, they received 150 subscriptions!

Stories like this show how the innovating expertise that Bayer’s I-Coaches are disseminating throughout the organization is paying big dividends in the form of great ideas becoming even better through a well-designed development process.

Whenever new ideas begin to surface in Bayer’s creation process, various members of the I-Team get involved. I-Coaches encourage their colleagues to write up brief descriptions and analyses of innovative ideas in the form of simple, one-page proposals. When appropriate, the ideas can simply be submitted to the immediate manager of the innovating person or team. But if this doesn’t make sense—for example, if the idea requires buy-in from more than one department or division to be implemented—the idea can be separately submitted to a local I-Coordinator. The coordinator’s job is to systematically review innovation ideas and provide prompt feedback. If the idea is promising, the local I-Coordinator can select it and move it to the next step in the review and selection process. Thus, the biggest job of I-Coordinators is in connecting and linking the various innovating teams, capabilities, and new ideas scattered around the organization. They are involved in the channeling, filtering, and selecting process by which a local idea moves from an isolated insight about the customer into a new proposed solution.

Bayer’s Catalyst Fund— Building Bigger Innovations

It is easy to see that members of the I-Team at Bayer, from the I-Coaches through the I-Coordinators, are deeply engaged in a wide range of innovating activities, facilitating the creation and dissemination of a constant stream of ideas for improving Bayer practices and products around the world. But their innovating work doesn’t stop there. When posts on the WeSolve forum, fast sessions led by I-Coaches, and other innovating activities surface a really big idea with the potential to generate major benefits for Bayer and its customers, another innovating system springs to life. This is Bayer’s Catalyst Fund, a corporate intrapreneurship program that shepherds such highly promising ideas through a funding and development process designed to select and foster the best concepts and turn them into practical realities.

The Catalyst Fund was launched in 2017. With the help of the I-Coordinators, 120 challenges with potential to spawn innovative projects were identified. Eventually 28 topics that showed unusual value-creating promise were selected by the I-Team in close collaboration with senior business leaders. They were then addressed by a small cross-disciplinary team, led by a Lean Startup coach, which was committed to rigorous experimentation and iterative testing of the concept, including fast prototyping. These projects received funding totaling €50,000 (equal to about $60,000) and had three months to explore their solution and pitch it to a venture board of senior executives and innovation ambassadors. For 11 projects that presented the most convincing data, further development and testing followed.

Over time, more challenges were channeled through the Catalyst Fund system; the same winnowing process was used to select winners that would be funded for further development.

One way to think about the Catalyst Fund is as the organ that connects Bayer’s horizontal innovating engine to its vertical execution engine. The tools used for testing and refining the raw ideas that emerge from the innovators are designed to ensure that only concepts that are ready to be absorbed into the company’s everyday operations make the cut.

Dr. Ouelid Ouyeder, who has been running the Catalyst Fund since 2018, says:

As of 2020, five Catalyst Fund projects have been successfully launched as new Bayer businesses. They range from a disease prevention program for cats and dogs being offered to veterinarians by Bayer’s France-based division to a training program for radiology physicians originating in Bayer’s Peruvian operation. More pilot projects are in the pipeline, and in years to come more Bayer businesses are likely to emerge as outgrowths of the Catalyst Fund.

“Innovation Is Contagious”: Lessons from the Bayer Experience

In recent years, as Bayer’s innovating engine has continued to mature, it has also evolved. During 2020, in response to the worldwide COVID-19 epidemic, practically all of the company’s innovating activities have migrated online, a pattern we’ve seen at many other companies as well. Sustainability—defined in both social and environmental terms—has become an increasingly important part of Bayer’s innovating program. The factors on which proposed new projects are measured now include, along with the likely financial results and the marketing possibilities, the positive social impacts that could be generated and the environmental costs and benefits to be expected. “In today’s world,” Dr. Lessl says, “there is no innovation that’s not sustainable, and sustainability needs innovation. The two are a natural and perfect fit.”

Company leaders have worked to make sure the new focus on innovating is being integrated into Bayer’s cultural DNA. Every learning program for Bayer employees now includes innovation as a central topic, and every list of core competencies used to evaluate new hires and current employees includes innovating.

Finally, the responsibility of the board in supporting innovation has expanded, as the role once filled by a single board member has now been handed over to the entire board, operating as the new, formal I-Committee. This helps to ensure that the focus on innovating from the very highest levels of the organization is never lost.

Some of the lessons from the Bayer innovating experience are familiar ones that align closely with the overall themes of this book. For example, Bayer’s Dr. Lessl points to the way innovation relies on teamwork and tends to grow from the middle and lower levels of organizations:

Innovation is a social activity, and connectivity is an asset. The image of the lone inventor is alluring, but almost always wrong. Innovation actually happens in teams, in cross-functional workshops, and through the involvement of many. It is also highly contagious. After we introduced the fast session concept, there were some countries where it took off, with fast sessions every week, and everyone wanting to get involved. This happened not because of a central directive, but because of the energy and skills of a few individuals.6

Other lessons from Bayer connect specifically with the role of the I-Coaches. The employees who participate most actively in Bayer’s innovating activities—the hundreds of I-Coaches and I-Coordinators who train their colleagues in innovating, lead innovating programs and workshops, and help develop innovative ideas into proposals that may turn into new processes, products, or businesses—are formally charged with the responsibility for this work. They are officially encouraged to devote 5 to 10 percent of their time to innovating work, and they earn so-called star points for each innovating task they perform, an incentive system that Bayer’s leaders refer to as “gamified.” When an I-Coach has earned 500 star points, he or she is designated an “advanced coach.” Advanced coaches have the opportunity to experience a new two-day training program at which they get to further improve their innovating skills.

Interestingly, however, Bayer’s Dr. Trill warns against incentivizing managers to innovate by measuring “vanity metrics”—for example, the number of innovative ideas that give rise to new business opportunities, or the cost savings or profit measures generated by an improved system. “Innovation is a tool to achieve the strategy of a business, not a purpose in itself; thus, innovation should be the natural way leaders leverage to drive their business,” Dr. Trill says. “That is why innovative behavior should be encouraged or requested, but individual results not incentivized.” The results may or may not happen, depending on circumstances. What matters is to define an area where the business needs innovation and systematically explore new opportunities through creativity and rapid experimentation to meet the real needs of the customers. If you do this, you’ll create ample opportunities for the results to emerge.

Beyond the cohorts of I-Coaches and I-Coordinators, all employees and managers are important in Bayer’s innovating ecosystem. On the most basic level, departmental and division leaders must be willing to give permission and empower employees to devote time and energy to innovating activities—even when this means “stealing” resources from their everyday execution work. Since managers are generally appraised and rewarded for the concrete execution results they achieve—sales racked up, products manufactured, customers served—they are tempted to give innovating short shrift.

Dr. Trill admits that this is a big challenge, even at an innovation-centric company like Bayer. To address it, the company has worked hard to make innovating attractive to managers. Making sure every site has at least one local I-Coach is one useful step. I-Coaches can help locally to solve problems, which often provides direct and immediate benefits to the business and thus to the managers. I-Coaches can also help managers to “fail fast” by triggering the most critical experiments first, reducing the resource costs involved in innovating.

Broader corporate support also helps to encourage managers to embrace innovating. The fact that Bayer’s top-level executives, especially the members of the I-Committee, go out of their way to publicly recognize and reward departments and divisions that do a good job of innovating helps to win support from the organization. For example, to encourage widespread use of WeSolve, board member Kemal Malik used to sponsor a regular contest in which employees who posted the best challenges on the online forum would be invited to dinner with Bayer’s top executives. Understandably, managers also enjoy basking in the reflected glory they receive when their frontline employees are lauded as heroes of innovating.

What’s more, increasing numbers of managers are coming to recognize that supporting innovating activities is a powerful way to attract and retain the best employees. People throughout organizations want the chance to innovate; when they are denied the opportunity, they are apt to go elsewhere. Dr. Trill tells the story of a local Bayer manager who discouraged one of his team members from getting involved in innovating projects because her daily work was too demanding and important. Within a few months, she had departed for a job at a rival pharmaceutical firm. When stories like this are shared through the grapevine, they spread the lesson that supporting innovating is smart business in the short term as well as the long term.

Perhaps the most important takeaway from the Bayer story is the way a giant multinational corporation with a rich history of achievement has been able to generate a new vibrant culture of innovation by building an innovating engine in parallel to its highly efficient execution engine—and then by finding ways to engage the majority of its workforce in keeping both engines humming.

This is not an easy task for any organization because the two engines are so different in their management styles and structures. The execution engine is about control. Because top management needs to maintain strict control over the activities involved in executing the chosen strategy, allocating scarce resources, setting operating targets, and monitoring results, it’s inevitable that most companies will create layers of hierarchy and sophisticated control systems that gradually discourage innovating behavior.

In contrast, the innovating engine is less about control and more about delegation, communication, collaboration, transparency, and team-building. It reflects a different managerial attitude that focuses on allowing individual employees with promising ideas to test, develop, and prove the value of those ideas. The innovating engine allows local departments to support individual innovators whose successful ideas may ultimately give rise to separate, self-supporting departmental or divisional units in a positive, long-term cycle of innovation and growth.

The differences between the execution engine and the innovating engine are stark. Yet Bayer has developed ways to train and encourage managers in every division and functional area to understand and value both styles of management and apply them when and where appropriate—a subtle, complex, yet vital leadership challenge.

In companies like Bayer that have found a way to make both engines operate efficiently, the differences between the two core engines of the organization, their management philosophies and practices, become increasingly clear to and internalized by everyone over time. When operating in execution mode, employees and managers have tightly defined job descriptions, elaborate planning processes, and control systems that guide resource allocation decisions. When the same people operate in innovating mode, they dedicate a portion of their time to legitimate, protected, and supported innovating activities within the organization that might be of potential value to a customer and to the company.

As Dr. Lessl says, “Innovation is contagious.” At Bayer, the beneficial infection of innovating practices is being spread companywide through a network of systems, processes, and connections that turn employees in every division and department into creators of the future.

KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM CHAPTER 9

• Innovating needs to occur throughout the organization. An I-Team—a formal governance and coordination structure dedicated to legitimizing, advocating, and sponsoring innovating and spreading information, insight, and practices conducive to innovating—can play a crucial role in making it happen.

• I-Teams can be structured in many ways, but most include a centrally coordinated unit of I-Trainers who are charged with training I-Coaches and local teams in the skills needed to generate and develop innovative ideas.

• Most I-Teams also include I-Coaches embedded across the breadth and depth of the organization, who help to guide local teams and individuals as they engage in innovating activities.

• Local I-Coordinators, also embedded in the organization, play an important role by making connections among innovators throughout the organization and helping to choose the most promising innovative ideas for further development.

• Within the I-Team, an I-Committee may be responsible for selecting the best innovative ideas, making investment decisions, and monitoring results to ensure the most promising ideas get the backing they deserve. From the very top of the organization, the I-Committee proactively advocates, promotes, sponsors, and supports innovating activities throughout the organization.