A Brief Overview of the Risk Management Process

A risk management approach underpins the entire business continuity and cybersecurity management processes. This chapter will provide a review (as opposed to a detailed description) of generic risk management practice. There are many publications on risk management—books, white papers, and Standards, and a number of these are listed in Bibliography.

Where Risk Management Is Used

People from different occupational backgrounds will view the term “risk management” in quite different ways. Some organizations view risk as an opportunity—usually to make money, for example, in the case of an investment bank considering funding a start-up operation. Others will see risk as having negative connotations, and it is this view that is relevant in both cybersecurity and business continuity.

ISO Guide73:2009 defines risk management as “coordinated activities to direct and control an organisation with regard to risk.” Anyone who undertakes business continuity work in an information technology environment will also be familiar with the term “disaster recovery,” and if we view this together with cybersecurity and business continuity, we might see that each of the three disciplines makes extensive use of risk management in order to understand what we are trying to protect and why.

Risk is at the very heart of business continuity, but when we talk about risk, it is easy to misunderstand the terminology, so let’s begin by looking briefly at its various components.

Risk is actually a combination of the impact or consequence of something happening and the likelihood or probability that it will happen. The impact or consequence comes as the result of a threat acting upon an asset of some kind, where that asset has a degree of vulnerability, and where that vulnerability gives rise to the likelihood or probability.

Figure 2.1 illustrates this.

Figure 2.1 A general view of the risk environment

Let’s look at a simple example.

If a computer is not protected with a password, anyone who has access to it can either steal the machine, and/or read, copy, change, or delete any of the application software or data on it. The machine itself, the application software, or data represent the assets; the threat is that some unauthorized and ill-intentioned person may obtain access to the machine and undertake some detrimental activity as a result; the vulnerability is the lack of password protection; the impact or consequence would be the damage to or loss of machine, software, or data. Separately, the likelihood will depend upon the attacker knowing or guessing that the machine is unprotected and having the desire to recover or remove software or data from it. The result is the risk.

Therefore: Risk = Impact or consequence × Likelihood or probability

All the same, even if the machine is protected with a password, there still exists the possibility that an attacker will try to guess or recover the password to gain access. The impact remains the same, although the likelihood is somewhat reduced.

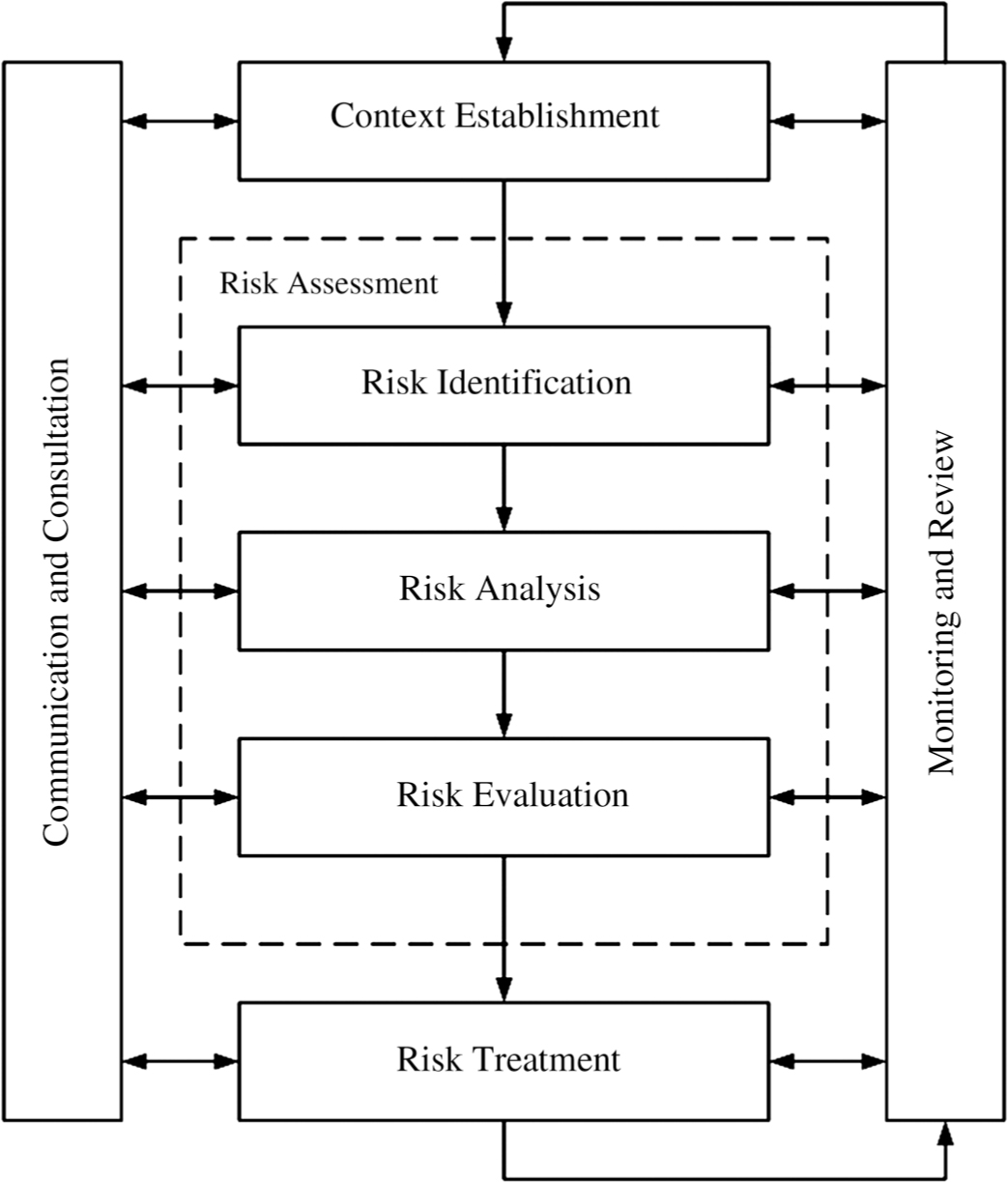

Understanding risk and planning for how to deal with it is known as risk management. There are five main components to this as shown in Figure 2.2 (taken from the international standard ISO/IEC 27005:2011—Information security risk management), and we’ll look briefly at each in turn, and expand on them later in the chapter.

Figure 2.2 The overall process of risk management

Context Establishment

This simply means gaining an understanding of the organization; how it operates; the environment in which it operates; its key objectives, products, or services; and which of these are liable to cause disruption to the organization if they cannot be achieved or delivered.

Within this, it is also important to understand the organization’s risk appetite. This is the level of risk the organization will accept for any individual asset or activity. For example, it may decide not to insure low-value items as the cost of doing so might outweigh the possible benefits. At the other end of the risk appetite scale, the organization may decide that the possible failure of a high-cost project could affect its survivability, and that it should not go ahead. Somewhere between these two arbitrary points will lie the organization’ risk appetite for any given asset or activity.

Risk Assessment

This next stage of the risk management process comprises three separate steps.

Risk identification is (as shown in Figure 2.2) the process of identifying the various assets, the threats that they might face, the impacts or consequences of their being disrupted, the vulnerabilities that they possess, and finally the likelihood or probability that one or more of the threats might be carried out.

Threats may arise from a variety of sources—man-made or natural, and there are some that we as individuals or organizations can do little or nothing about, for example the threat of a hacking attack or a flood. We may be able to reduce the impact if threats take place, or possible to reduce the likelihood that they will occur, but the threats will always remain.

Chapter 5 deals in much greater detail with the kinds of cyber threats we are likely to encounter, but also briefly covers noncyber threats that can nonetheless result in an impact on an organization’s cyber activities.

Impacts or consequences represent one part of the risk equation, and may also take many forms. They can be financial, reputational, operational, legal and regulatory, environmental, and people-related, or can result in the degradation of services. Often, there is a chain of consequence involved, and what begins as a people-related impact may develop into an operational one, leading for example to both financial and reputational impacts. It is important when conducting risk identification that these chains of consequence, illustrated in Figure 2.3, are not overlooked, since cumulatively, they can far exceed the originally identified impact.

Figure 2.3 A chain of consequence

Impact or consequence can be stated in one of two ways—qualitatively, which is highly subjective, using descriptors such as “low,” “medium,” or “high”; or quantitatively, which is more objective, with numerically defined values such as $100,000 or 1,000 units per month.

Since the qualitative approach is often rather too subjective to permit an accurate risk assessment and the quantitative approach is usually much more complex and time-consuming, a half-way house is sometimes used, and this is known as semiquantitative assessment, in which bands of impact are given.

Table 2.1 illustrates how these semiquantitative assessments can be developed, and these are covered in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Table 2.1 Typical impact scales

| Level of impact | Financial | Reputational | Legal and regulatory | Operational | Well-being |

| Very low | Losses of less than $100K | Negligible negative media coverage | Threat of possible action | Partial failure of one service | Little or no impact on staff |

| Low | Losses of between $100K and $500K | Some local negative media coverage | Penalties up to $10K | Total failure of one service | Minor loss of unskilled staff |

| Medium | Losses of between $500K and $1M | Some national negative media coverage | Penalties between $10K and $50K | Partial failure of multiple services | Major loss of unskilled staff |

| High | Losses of between $1M and $5M | Major national negative media coverage | Penalties between $50K and $100K | Total failure of multiple services | Minor loss of skilled staff |

| Very high | Losses in excess of $5M | Worldwide negative media coverage | Penalties in excess of $100K | Total failure of all services | Major loss of skilled staff |

Vulnerabilities again are many and varied. Some will be so-called intrinsic vulnerabilities, which are present in all situations. For example, whether it is deliberately or accidentally applied, a strong magnetic field can erase the contents of a disc drive. Others will be so-called extrinsic vulnerabilities, which are present when some action has either been taken or not taken, for example not changing a default password.

Vulnerabilities are covered in greater detail in Chapter 5.

There is some debate as to the order in which impacts, threats, or vulnerabilities should be assessed, but more importantly than the sequence of these is that they must all be carried out in order to complete the risk identification process.

Likelihood and probability represent the other half of the risk equation, and it is important to understand the difference between them. Likelihood is a qualitative term, and again is often highly subjective. We may characterize the likelihood of something happening as being low, medium, or high. Probability, on the other hand, is a quantitative or objective measure, and is often expressed in frequency terms such as a “once in ten years” event or in percentage terms such as a 20 percent chance that it will happen.

As with assessing impact or consequence, likelihood or probability can also be expressed in semiquantitative terms, as shown in Table 2.2. This allows some degree of flexibility while retaining defined boundaries for the assessment.

Table 2.2 Typical likelihood scales

| Level of likelihood | External cyberattack | Internal cyberattack | System failures |

| Very low | Once a month | Once every 3 months | Once a year |

| Low | Once a week | Once a month | Once every 6 months |

| Medium | Multiple times a week | Multiple times a month | Once every 3 months |

| High | Once a day | Once a week | Once a month |

| Very high | Multiple times a day | Multiple times a week | Once a week |

Finally, before the risk identification work commences, the means of approach—whether qualitative, quantitative, or semiquantitative—must be agreed, and in the case of the semiquantitative approach, what are the boundaries that define both impact and likelihood.

Next in the process of risk identification comes risk analysis. This involves plotting the risks we have identified on a risk matrix similar to that shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4 Example of a typical risk matrix

The values placed in each square of the matrix can be chosen in order to provide a form of weighting to the resulting analysis, where for example, the increase of impact from “trivial” to “minor” is considered to be of lesser importance than the increase from “possible” to “likely.”

Using the above-mentioned matrix as an example, if a risk has been assessed as having a “major” impact and as being “likely” to occur, its value from the matrix would be rated as 20, and this will allow us to rank it against other risks of different ratings. When we move to the next stage, that of risk evaluation, this ranking will determine the priority in which we treat the risks. It is important to understand that the choice of five scales for each of impact and likelihood is arbitrary. Some organizations choose to use a greater number, affording more granularity; others choose an even number of scales in order to avoid too many risks appearing in the middle ground.

Once plotted against the matrix, each risk can then be seen in the overall risk context, allowing the organization to deal more easily with the most urgent risks before those of lesser significance.

One final point on risk identification—if there is little or no impact or consequence, or if there is little of no likelihood or probability, then it follows that there is little or no risk. This does not mean we can ignore it completely though, as we shall see in the next section on risk treatment.

All risks should be recorded, and this is usually performed in a risk register that documents details of the threat, vulnerabilities, impacts or consequences, likelihood or probability, and the level of risk assessed. Once the risk evaluation process has been undertaken, the register may also contain details of how the risk is to be treated, by whom, and the proposed timescales.

Risk evaluation is the final stage in the risk assessment process, and offers the organization a number of choices of how to deal with the risk in question, and we shall deal with them in greater detail in Chapter 6.

At the highest or strategic level, there are four choices:

Avoid or terminate the risk. The organization may simply decide not to do whatever it is that would cause or allow the threat to materialize; for example, not to build a data center in a flood plain, not to install untested software, or not to allow a casual contractor to have root access to key operational systems!

Share or transfer the risk. This involves making a third party partly or even wholly responsible for dealing with the risk, although ownership of the risk must remain with the organization itself. This is usually carried out by some form of insurance, but the organization must be certain that any insurance policy has been thoroughly examined and approved by its legal department, since insurance companies will occasionally exploit a loophole in order to avoid paying out.

Reduce or modify the risk. While it is uncommon to be able to remove or reduce threats, it is much more usual (and often relatively straightforward) to reduce the likelihood or the probability that the threat will occur. This is often a simple action, such as maintaining the patch levels of operational software, thus avoiding unnecessary exploitation of a vulnerability, or by carrying out regular backups of business-critical data.

Risk reduction or modification sometimes does not completely reduce the level of risk to zero or near-zero levels, and a certain amount of so-called “residual” risk remains, which must be recorded and monitored on an ongoing basis.

Accept or tolerate the risk. When no other options are open, or if the level of risk is very low, then it can be accepted. However, it is important to understand that this does not mean that it can be ignored. Risks that are accepted must be reviewed periodically in order to ensure that the level of risk has not changed, which would require that the choice of avoid/terminate, share/transfer, reduce/modify must be taken again.

Risk Treatment

Once the strategic choice on how to deal with the risk has been made, we move to the tactical level. Here, there are four types of treatment:

- Detective, in which we use systems or human observers to discover when and where a cyber threat is being or has been carried out;

- Directive, in which we dictate actions that must be taken (and those that must not) in order to improve or maintain good cybersecurity;

- Preventative, in which we put measures into place that will prevent a cyber threat from being carried out or will reduce its impact;

- Corrective, in which we fix a problem that has occurred or is in the process of occurring as a result of a cyber threat being carried out.

Each of these tactical options will have one, two, or three operational choices:

- Procedural measures. These may be in the form of a statement in a policy document, for example a process that must be followed, or a work instruction that informs people how to go about undertaking some action.

- Physical measures. These usually involve some form of hardware, such as fences, gates, and entry control systems.

- Technical measures. These will include such areas as intrusion detection software and firewalls.

The choice of tactical or operational solution will depend greatly on the specific risk being addressed, and will often be agreed upon by a team of experts rather than by a single individual, and there is also the possibility that a risk may be addressed by more than one form of strategic, tactical, or operational approach, each making its own contribution to the overall treatment plan.

Communication and Consultation

It would be difficult (if almost impossible) for an individual to undertake a risk management activity alone. He or she would normally always require input from other areas of the organization in order to understand better how it works, what its deliverables are, and how disrupting events might affect these.

It will also be key to refer the individual risk assessments back to these sources in order to verify that all the input has been correctly recorded, interpreted, and assessed. Likewise, those other areas of the organization will be vital to helping develop the proposed solutions, and their input to that part of the process will often be essential in compiling business cases in order to obtain funding for the costlier work, especially if the funding must be procured by their departments.

Business Cases

It is worthwhile taking a brief look at the fundamentals of business cases, since these are generally the means by which we are able to obtain both capital and ongoing operational funds for the work the organization must undertake.

Unless you’re lucky enough either to have an unlimited budget or a very understanding chief financial officer, you will certainly be obliged to make a formal request for the funds. There is usually a standard process for this in most organizations, and while this may vary in the detail from one organization to another, the decision-making panel will usually have certain general requirements.

You should be able to state the following:

What you want to spend the money on. This need not be a highly detailed list, but should include the key items, such as IT systems, software, network equipment, people, or outsourced services.

How much you plan to spend. This must cover both the capital items described earlier, and funds for specialist staff and contractors and also for ongoing regular service contracts such as maintenance upgrades and support.

When you will need to spend the money, so the finance department will know when to allocate funds.

The benefits of spending the money. This is often the most difficult area to cover, since there may be no obvious financial payback. Instead, you will need to focus more on the likely financial impact on the organization if a threat materializes. However, don’t be too tempted to focus purely on the negative—senior executives are often wary of scare tactics and may feel they are being manipulated.

Since your work may be competing for funds with other (possibly revenue-generating) projects, you may find it advantageous to meet as many of the decision makers as possible before presenting your case and to briefly outline the project to them, allowing them the opportunity to ask questions and allowing you time to be able to research the answers, so that when it comes to the actual presentation, they are already familiar with the project and you will already have the answers to their key questions.

Most executives are busy people and dislike having to read through pages of technical data, so the material you present should begin with a one- or two-page executive summary that provides all the high-level information they need, but with any relevant background material behind it.

The presentation—if you are required to give one—should be brief and succinct. Ten minutes and ten slides should cover the points listed earlier. Always ask if they have any concerns or questions, and try to be sufficiently well prepared to be able to answer them on the spot. If not, be prepared to admit that you need time to find the answers, and tell them when you will be able to provide them.

Monitoring and Review

Clearly, once you have taken actions to treat a cybersecurity issue, you need to check whether or not the treatment has worked as expected. Whenever possible, the activity that delivers the treatment should include one or more tests to verify its effectiveness, and should allow for the treatment to be adjusted as necessary to make improvements. The results can be added to the risk register, allowing interested parties to see what has been achieved and how you have arrived there.

The fact that a risk has been treated, however, does not bring the matter to an end (unless the avoid or terminate route has been taken), as there will usually be some residual risk.

The risk should be reviewed—and if necessary the treatment should be retested—at agreed intervals to ensure both that the treatment is still delivering the expected results and that the level of risk has not changed.

If the organization has an internal audit function, it may wish to be included in such reviews, and in the case of extremely high-risk areas, may even insist on running the reviews itself.

Some people have a fear or distrust of internal audit, partly because they frequently bring more work as the result of reviews and partly because it brings about the feeling that you are not fully trusted. Involving them in projects to treat cyber risk may bring positive benefits, however, since their support when presenting business cases can easily swing the decision in your favor.

Summary

In this chapter, we have reviewed the basic principles of risk management and explored the terminology used. In the next chapter, we will examine the next stage—that of establishing the context of the organization and understanding its information assets, which represents the first part of the overall risk management and business continuity process.