Business Liability

Liability does apply with respect to the amount of the oil spill.

—Ken Salazar, U.S. Secretary of the Interior,

addressing the Gulf Oil Spill in 2010

Learning Objectives

- 1.Describe the concept and scope of business liability.

- 2.Summarize the effects of insurance and business organization on liability.

- 3.Explain the role of courts, mediation, and arbitration in addressing liability claims.

What Is Business Liability?

For business owners, opportunities to sell goods and services are exciting. But revenue and profit usually require significant resources, and many businesses incur liabilities—debts or other obligations owed to others—along the way. Liability includes loans borrowed to finance the business and other obligations spelled out in business contracts. If a business fails to meet its contractual obligations, a liability remains and those owed will seek compensation so long as it remains profitable to do so.

Sometimes the consequences of business liability are easy to predict and plan for; other times not. For a business loan backed by equity in the business, the lender goes after the equity if the loan goes unpaid—a predictable outcome. Actual debt recovery may take considerable time and expense, but this contingency is relatively easy to plan for. Many other standard business contracts entail liabilities that are fairly easy to foresee, but not all. Furthermore, the scope of business liability extends beyond contracts, and the great reach of potential liability makes it even harder to foresee. This book focuses on business liabilities whose consequences are relatively hard to predict, but can nevertheless be identified and prepared for in some way.

Business liability comes from many directions, so many that a detailed account of all possibilities is impossible. A business cannot foresee every form of liability, but its managers and owners should develop an intuitive understanding of liability by considering the business’s relationships with society. It is not just desired relationships that might be listed in a business plan, but actual ones.

To get a grip on the real scope of business liability, you have to think big, have a big picture in mind, a big idea. One big idea discussed in this book is the social contract. For a business owner or manager who wants to avoid a business liability mistake, it is useful to take the view that businesses have liability because they are bound by a social contract to avoid certain harms to others. The social contract does not take the form of a tidy 5-page or 10-page document that a business signs and sends to the government. It does not necessarily stay the same over time, and may or may not ultimately be fair. It does reflect and signify the body of laws and regulations that a business faces and is colored by the economic, social, and political institutions of the day. A social contract can serve as a theme or umbrella for myriad elements of business liability—and so can serve as a conceptual model to simplify some aspects of liability faced by business owners and managers. As a practical matter, for the purposes of this book a social contract is an idea or framework that serves to define and limit the rights and responsibilities of society’s members.1

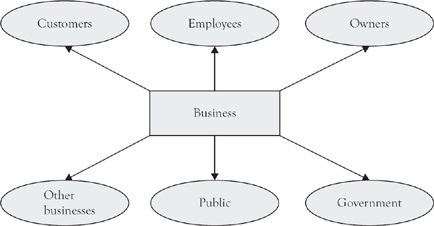

The scope of possible liabilities that a typical business faces is mind-boggling. It is key to have some hunch, or intuition, about where liability comes from and the impact it has on businesses. A good hunch about business liability can be formed by thinking about how a business stands in social contract with others. Each business has some implicit social contract with society, with liability for its actions (or inactions) that cause harm or loss to others. Relationships between a business and society are always sources of liability, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Sources of business liability

In the United States, a social contract is partly framed by the U.S. Constitution and its amendments, as well as other laws introduced by the federal government and upheld by the courts, treaties and agreements with other nations, the laws of state and local governments, and the opinions of the court on cases tried before it. Each of these foundational elements may create rights and duties that collectively frame the social contract. A business that breaches the contract causes a loss to society, a liability.

The American social contract, as a catchall for the various rights and responsibilities we bear to one another, is formidable and far-reaching. Our system of justice, our rule of law, acts to right imbalances and provide opportunity for wrongs to be righted. America’s legal system supports the social contract—or rather the rights and responsibilities it is intended to signify—with remarkable commitment and vigilance, despite the system’s imperfections. The same is not true in all countries. In the Philippines, a country in southeast Asia, I spent a year in high school in the 1980s and lived with a host family. My host father was a trained lawyer, but could not find work because the legal system had become weak and lawyers were of little use, so he ran a convenience store instead at the University of the Philippines. Matters have improved greatly since that time, but weak legal institutions and corruption continue to be problems for law in the developing world.2 In many countries, a business can bribe its way out of many obligations to society. In America the bribe is less reliable, in part because government officials are better paid and so less benefitted by bribes economically and also because a centuries-old tradition of government propriety still carries momentum—despite many lapses.

For a business manager pondering the scope of the company’s liability, it is useful to develop an intuitive and informed sense of what is owed to society, as if the company were bound by a social contract that could be spelled out, at least in principle. This sense of obligation does not require a knowledge of all U.S. laws—not even lawyers or judges have that. The relevant social contract includes a set of rights and limitations on behavior that protect people from harm, and a basic understanding of the legal scope of harm is a must. As noted in the Preface, the book you are reading is no form of legal advice, but the economics of business liability and damages is framed by the legal system, so a discussion of the legal landscape is inevitable.

A good starting point for assessing business liability is to briefly detail the six relationships shown in Figure 1.1. Loans and other business contracts create business-to-business liability, but each business has customers and—like it or not—potential liability in their customer relationships. Employees are owed paychecks but also owed fair and respectful treatment, a form of liability shaped by the social contract between the employer and the employee. For businesses big enough so that their actions are not one and the same as that of their owners, business owes its owners, and so is liable to them. All businesses know about taxes—one sort of debt owed to the government, and some end up with other ties to assets that lie in the government’s reach, and so more liability. Furthermore, general members of the public hold a potential relationship with a given business, by sharing the same road space on a given day, the same communication network, water supply, or other component of our common space. All of these relationships carry potential liability.

To illustrate, consider my business activity as the author of this book. I get paid royalties by my publisher, to whom I have sold the rights to this book. The publisher is my customer and our contract spells out my obligations, including publication deadlines, quality guidelines, and book length. I have no ghostwriter or other employees, nor other business owners, so no liability there. I do have liability to other businesses, as I am a university professor and my book counts as a scholarly contribution that my university takes credit for supporting. Shared credit implies some liability on my part to ensure quality and protect the university’s reputation. This book deal on my part is straightforward tax wise, and my liability to the government is otherwise transparent.

Where do you, dear reader, fit into my liability as book author? You are part of the public at large. I am obliged to avoid having boxes of my books fallout of the trunk of my car and smack your car’s fender on the roadway. The publisher owns the words you are reading, but I profit from book sales. Do I not also bear obligation to the reader, for the book itself? That is the hardest part of my liability puzzle. I have designed the book to improve your understanding of business liability and economic damages, with no intent to harm anyone. It is advertised as a book of ideas, not advice, so cannot be said to poorly advise. This book contains examples but omits names and identifying details of real people, so it cannot wrongly characterize anyone in the general public. For these reasons my legal duty to you is pretty limited.

Insurance

In this book we will be talking mostly about business liabilities that are hard to anticipate; for example, product defects, which unlike debts and interest payments, are hard to predict.

To deal with unexpected liabilities, an elegant solution is insurance—a contract in which one party meets the obligations of another, under specific conditions. Pay a premium and the nightmare of ruinous mistaken harm vanishes. Indeed, insurance markets have made possible much business activity that could not otherwise take place. But the insurance company is not your friend. It plays a risk game that it wins on average, but you are a risk, not a business partner.

Insurance makes the social contract more workable by lessening the burden on courts to enforce the contract’s obligations. Insurance companies can quickly assess damages and provide remedies, but courts cannot. Insurance works so well that it has been assigned a special place in the social contract, an institutional role alongside the courts. All drivers must buy automobile liability insurance; many businesses must buy workman’s compensation insurance, which presupposes the existence of insurance markets. Additionally, the government provides insurance to cover unemployment and disruptions in the market for insurance itself, such as insurance company bankruptcy.

Insurance is good, but insurance markets are like casinos. The insurer’s pursuit of profit is good for the social contract and business, but insurers know the contract better than most of their customers do. Big insurance companies have armies of lawyers. They know today’s law and anticipate its changes tomorrow.

Insurance companies cover some business liabilities, but not all. The insurance agent will sit down with a business owner and discuss a range of liabilities, touching on some or all of the points shown in Figure 1.1. But liability is a thing to be identified by the business itself, preferably with a lawyer’s input, before any meetings with insurance agents. Insurance helps to mitigate the business’s risk of liability, but insurers lack the exhaustive knowledge of any specific business that would be needed to fully address this risk. Mitigation is not absolution. The liability buck never gets fully passed from business to its insurer.

Businesses look to their insurance policies for peace of mind, but the insurer sees them as loaded guns. Every policy is written to cover some stated form of liability, but is otherwise designed to minimize liability’s scope. This scope is whittled down until it just meets the demands of the social contract. Anything extra would present more risk for the insurer, and less profit.

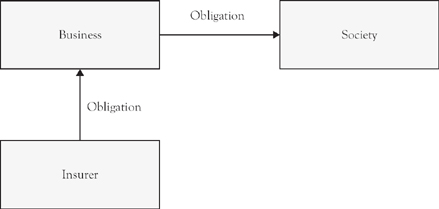

When a business causes harm, society comes after it and not after its insurer. I illustrate this in Figure 1.2. Business has an obligation to society, and its insurer has an obligation to the insurer. It is easy to suppose instead that the insurer assumes the business’s obligation. For example, in routine car accidents a claim is usually made against a driver’s insurer and not against the driver directly. This saves time and money, but the true obligation lies with the party that caused harm. The less a business knows about how this works, and the more it relies on an insurance company to advise and guide it, the more money the insurance company makes and the greater liability the business faces. Insurers do not want businesses to read this book!

Figure 1.2 Business, society, and the insurer

Insurance companies want to cultivate ongoing relationships with most businesses they serve, but this goodwill dries up for customers who become stand-out risks. Businesses that cause harm become less desirable insurance customers, because they pose a greater perceived risk of future harm. Stand-out risks are lemons to the insurer. For lemons, insurance companies have no goodwill, and they will minimally service their policies. They may also drag out the process, with years of court proceedings needed to settle a matter, and regardless of the damage, such proceedings may diminish a business’s reputation. In states like New York, where anyone can track almost every lawsuit’s progress online, and chat online about it, dragged-out liability disputes carry a potentially huge reputation cost for businesses.

Insurance policies are just business contracts—agreements that can be breached. The insurer will try to avoid breach or risk the ire of regulators. Deep pockets help, but some insurance companies still go belly up. State governments know this and provide some backup insurance funds. These create a possible economic problem of moral hazard—an excessive shift of risk from one party to another, due to risk avoidance, by which businesses underinsure with the confidence that the government will pick up the remaining tab. But governments are onto that trick, and woe to the insurer that thinks otherwise. Every business should, however, be aware of any such backups, and should carefully study the financial health and customer satisfaction of would-be insurers, before buying liability insurance.

Business Forms

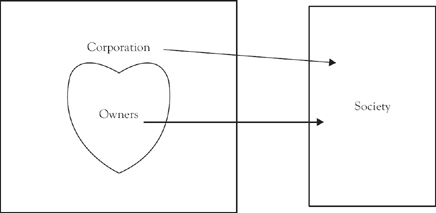

Business liability is a burden with the potential to cripple innovation and economic growth. Mindful of this, the framers of America’s social contract capped financial liability via the corporation. A potential customer or service provider that does commerce with a corporation has limited recourse if commerce goes bad, but the existence of corporations also provides more economic opportunity and choice. The same idea applies to other forms of limited liability business entities, including the limited liability company (LLC), type S corporation, and limited liability partnership (LLP).

The existence of corporations demonstrates a sort of hands-off, or laissez faire, approach of lawmakers to financial gain and loss. With this hands-off approach, lawmakers concede that a full dose of liability in the social contract would be toxic to the economy. But it is an uneasy concession, with limited scope. The corporation’s structure protects its owners from losing their homes if a business deal fails, but does not absolve them of responsibility for harms that the corporation may cause. Recalling the diverse forms of liability shown in Figure 1.1, every corporation has liabilities that exceed its financial commitments. All these extra liabilities can potentially pierce the corporate veil and pass through its owners, as shown in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Corporate liability to society

The prospect of the corporation’s owners bleeding cash from their savings accounts, to cover corporate liabilities, may seem unfair. But the threat of such pass-through liability protects society from having every business formally pose itself as a corporation, or a bunch of them, with modest assets that seriously under-represent the capability of the business to meet its obligations to society. Abuse of corporate structure is a moral hazard, which the corporate veil piercing discourages.

Mindful of chinks in their armor, corporations guard themselves—and their owners—from liability risk via insurance. This double armor provides stability, but not quite peace of mind. As discussed earlier, insurance markets provide only limited protection from liability claims. A corporation’s true scope of liability is not known to its insurers, only to itself. Knowing this scope of business liability requires careful self-study and good understanding of the social contract.

The Legal System

Most business liabilities that go unpaid never end up in court. Instead they get negotiated, settled via insurance, or quashed in bankruptcy. But liability negotiations are, in effect, always done on the courthouse steps. If negotiations break down, the courthouse is a step away. Insurance settlement, for sizeable liabilities, is always a negotiation between the claimant and the insurer, and again takes place on the courthouse steps. If the claimant faces a lowball insurance offer, they can hire a lawyer who can further negotiate or go after the insurer directly in court. The choice of bankruptcy, too, is made with a view to liability claims that might otherwise play out in court.

Whether or not they end up in court, all business liabilities are framed by the legal system. The business manager needs a basic understanding of the system when dealing with each liability claim. The American legal system identifies unpaid liabilities as a harm to society, a breach of the social contract. The civil law system3 provides opportunities for those harmed to seek a remedy. Anyone seeking a remedy must tell the court which sort of harm is claimed. These include torts—one party’s wrongful harm to another, notwithstanding any business contract between them, and also breach of contract—one party’s wrongful harm to another caused by failure to uphold a business contract between them.

Torts are a catchall that covers almost every business liability other than those specified in a business contract. Torts, each a harm inflicted on society, include intentional harm, negligence, nuisance, and trespass, and each works pretty much as its name suggests. A manufacturer that foolishly uses the wrong screws to hold its product together, causing injury to customers, commits negligence. An ageing paper mill that decides to keep operating despite a broken fan system—thereby polluting a nearby town—commits nuisance. If the mill’s staff crosses a farmer’s land with heavy trucks, in a rush to fix the fans, they commit trespass. Related to the idea of trespass is the wrongful taking or laying hold of property, itself a tort.

The scope of torts is as broad as the sorts of harm that the courts intent to remedy. For example, consider the general idea of property—anything tangible or intangible that is owned by a person or an entity, and the right to possess, keep, hold, use, enjoy, and dispose of what is owned. A farmer’s land is property, but so is a special method that the farmer may have devised to process his crop for delivery to market4—a form of intellectual property.

Claims of tort and contract breach are brought to a court, and if deemed in good order will trigger a trial or other court-ordered proceeding. At the trial’s end the court will rule on the claim, based on evidence presented by the claimant and defendant legal teams. To make its ruling, the court will weigh and interpret the evidence in light of existing law, and also in light of existing court decisions and commentary on similar past cases—the common law tradition.5

For torts and contracts, past cases form an important source of law. The U.S. Constitution, and its 27 amendments, says nothing specifically about torts or business contracts. This is because the framers of these documents saw in the existing court system a sound means of addressing these wrongs. For business liabilities, the claimant acts as plaintiff, bringing the case to common law court, and the business is called to answer in its defense.

Each U.S. state has had, since its inception, a common law court system to deal with torts and contracts, and while states’ approaches to these matters vary, the federal government has not found the discrepancies so egregious as to impose a national standard or code.6 It has, however, supplanted state courts with a system of federal courts. The decisions of both state and federal courts can be challenged by the litigants (plaintiff and defense teams), with appeal to the corresponding appellate court. If unsatisfied there, litigants can further appeal to the corresponding supreme court—state or federal. Some state supreme court cases can be appealed to the federal supreme court.

A legal liability is any situation, identified by law, where an individual, a group, or an organization is found to bear obligation to another. A business’s legal liability is then any situation, identified by law, where a business is found to bear obligation to an individual, a group, or an organization. To try a liability claim, the court often spends a lot of time dealing with evidence and protocol, and must complete the challenging task of interpreting liability in terms consistent with the will of Congress and the court’s prior opinions. Legal teams, for plaintiff and defense, know that judges look to laws (statutes) and past court opinions (precedent) to decide matters, and so they research statutes and precedents as they prepare their cases. Legal research, preparation of evidence, and performance in court are all costly for the legal teams, and so costly for their clients.

A bench trial—a trial with a judge and no jury—is work for the court, a jury trial is more so. The jury examines evidence but knows little of relevant statutes, legal precedent, or court procedure. The judge must instruct the jury so that their opinion, or findings, reflects the logic of the relevant law. If it does, then the judge’s decision, or holding, generally agrees with the jury’s findings, otherwise not.

Our legal system is an expensive way to deal with business liability claims. It is cheaper to settle a case before it reaches trial. In economic terms, the claimant should accept any negotiated offer that leaves them with more money than they would get by going through the court system. The profit-minded business sued for liability should never make an offer that leaves the claimant much better off than they would be if they went through the court system, since a lower offer would still keep the lawsuit out of the courts. The same maxim holds for the business’s insurer.

The relatively few business liability cases that end up in court do so because the claimant anticipates a higher net gain from going to trial than any settlement offer they have received from the business or its insurer. Knowing how costly trials are, the business should prefer instead to raise the settlement offer above the threshold value that induces settlement, unless the business believes that the claimant’s expected trial outcome is too optimistic. In a simplified economic world where everybody holds the same expectations about what will happen, no business liability case would go to trial!

Substantial differences in expectations, which bring business liability cases to trial, can reflect differences in the information held by plaintiff and defense teams. However, the court’s rules of discovery usually serve to expose secrets and minimize differences in information. The teams might also have different opinions about the legal merits of the positions advanced by each side, or how these positions will be received by the court. This can happen, for example, if the defense lawyer has lots of experience with the judge and court at hand, while the plaintiff lawyer does not.7

For business liability claims that do not get settled immediately, the threat of a costly lawsuit often looms above further negotiations, but cheaper forms of dispute resolution exist. Mediation—dispute resolution facilitated by a neutral nonbinding third party—is relatively quick and procedurally simple. For business liability mediation to be useful, the business and its liability claimant must have different expectations about the mediation outcome; otherwise their common ground would beg settlement beforehand. Successful mediation leads to discovery of evidence that establishes common ground, so ending the dispute. The same holds true of a court trial, but the court’s decision is binding. Between these two forms of dispute resolution is arbitration—dispute resolution facilitated by a neutral binding third party, cheaper than a trial and sometimes built into contracts as a required substitute for trials.

Example

In this book we will explore a range of business liability examples, some more complex than others. As a simple starting point, consider a hypothetical company called Rent that rents trailers to construction companies. Rent does business in the Midwest and leases all its trailers from a national manufacturer called Best, with each trailer leased for 5 years. Over time, Rent gets more and more trailers from Best, but then finds a better deal from a local manufacturer. Rent returns all the Best trailers, most of which have time left on their 5-year leases. The lease contract allows such a return, but specifies that all unpaid installments on the trailers are due at the time of return. Rent pays none of these future installments, and so faces a business liability claim equal to the total of all unpaid future installments; suppose this is $500,000.

Best, having a half million dollar claim against Rent, tries to collect. If it has some other form of business engagement or contract with Rent, it may try to prompt payment by business retaliation, or a threat of retaliation. If no such “stick” is in its arsenal, Best will consider filing a lawsuit against Rent, a costly undertaking that will hopefully still net Best a good share of the claimed half million. Contract law provides this opportunity via a claim of contract breach. There is some uncertainty about the lawsuit’s outcome: Will the judge find it reasonable that payment for all future (but void) rental periods was actually due at the time of the rental property’s return? Will Best collect interest on the debt, and if so at what interest rate?

In this deadbeat renter dispute there is an economic principle—the time value of money—that can help the court decide the outcome. According to this principle, there is usually an advantage to receiving money earlier rather than later, and so the payment of all rent at once leaves the renter in worse shape (and the rental company in better shape) than if rent had been paid on its regular schedule. The value of this extra advantage depends on market rates of interest and can be estimated. The court might hold that the deadbeat renter pay its due without paying the “extra,” or not, depending on the wording of the contract.

This simple example illustrates business liability, with some uncertainty and economics involved, but the liability itself is predictable—a company bails on a rental contract, thereby triggering a liability claim for unpaid rent. In the remainder of this book, I focus more on economic damages that arise in liability cases where the liability claim itself is not so easy to predict. Such cases include personal injury, wrongful death, wrongful termination, and intellectual property loss.

- 1.Two friends set up a bagel bakery—Big O Bagels—in a rented building in a downtown area. The bakery is run as a partnership. It has three employees, and the owners take turns coming into the bakery each day to manage it. Give an example of a liability in each of the following groups, and the debt owed by the business in each case.

- a.Customers

- b.Employees

- c.Owners

- d.Other businesses

- e.Government

- f.General public

- 2.Suppose that a veterinarian wants to set up a veterinary clinic in Memphis, Tennessee.

- a.With regard to its relationships with customers, employees, and the general public, what forms of liability insurance is it required to hold? (Check online.)

- b.Does the state of Tennessee provide a liability insurance guaranty fund that kicks in if the veterinarian’s insurance company goes broke? (Again, check online.)

- c.Find an insurance company online that provides one of the liability insurance types required of the clinic in Memphis. Are a sample insurance policy and pricing available online? Why or why not?

- 3.U.S. courts have a love–hate relationship with corporations. Concerning the publically traded corporation, courts have refused law offices to take this business form, or even to take on nonlawyer owners. Explain the court’s likely intent here, in terms of the social contract.

- 4.In the Gulf of Mexico oil spill in the year 2010, five million barrels of oil reportedly leaked into the Gulf due to an oil rig explosion that also reportedly killed 11 people and injured 17 more. Leaked oil also killed fish, birds, and other wildlife and polluted private and public lands. A claimed cause of the explosion was a defective cement wall on the oil rig.

- a.Using appropriate legal terms defined in this chapter, identify the basic types of wrongful actions that may have occurred in the oil spill.

- b.Describe the potential scope of business liability for the oil company in terms of possible harm to society via its constituents:

- i.Customers

- ii.Employees

- iii.Owners

- iv.Other businesses

- v.Government

- vi.General public

- 5.Businesses can be liable for harm they do to most anyone. Figure 1.1 lists six groups that may be harmed by a business’ actions. For each group, name a type of business that might have a special liability for harm or damages done to that group.

- 6.One way that a business can deal with liability is to let their insurance company be in charge of identifying any such liability and arranging insurance coverage for it. Discuss possible problems with this approach by contrasting the information and incentives of the business owner with the information and incentives of the insurance company.

- 7.Over the last two centuries, changes in the U.S. legal system have increased the scope of businesses liability, imposing a greater burden on businesses to avoid harming others. Why might this be true?

1The origins of the philosophical idea of social contract lie in the classical works of Hobbes (1651), Rousseau (1762), Locke (1689), and others, with more recent contributions by Rawls (1971) and Sen (2009). An essential point in this literature is that people collectively enter into a social contract in order to get some benefits from others, while giving up some personal liberties along the way. The existence of a social contract, in these terms, seems obvious, but the existence of a grand, encompassing, and comprehensible social contract is unclear, which sinks the idea that society might actually be actively participating in it. As a practical matter, a social contract necessitates an agreement among members of society, defining and limiting the rights and duties of each. In the narrow focus of business liability, particularly in a given industry, this specialized notion of social contract is intelligible and useful.

2The Philippines and many other relatively poor countries have relatively high levels of corruption, while the United States and other relatively rich countries like Germany, Japan, and Australia have relatively low levels of corruption. See, for example, the Corruptions Perception Index 2014 available from Transparency International online.

3Substantively, civil law means the set of laws concerning actions that are noncriminal yet against society’s interests.

4For example, this nation’s first president George Washington developed and implemented improvements on the common sort of drill, plow, barn, and threshing method in his days of farming.

5Common law, manifest operationally as a civil procedure, relies on the court’s current and past actions to determine case outcomes. This contrasts with the civil law procedure in which the judge relies on written laws—rules and statutes—rather than on past case decisions. In practice, the U.S. legal system’s procedures permit judges some latitude in their use of statute versus precedent.

6A model code of torts and contracts has been developed by the American Law Institute—a group of legal scholars, lawyers, and judges, over the last 90 years, and is sometimes cited in court decisions.

7For liability cases that go to trial, a bench trial is quicker and less costly than a jury trial, and carries more uncertainty. To prefer a jury trial, the plaintiff or defense must expect that the jury’s findings will deviate favorably from what the judge’s holding would be in a bench trial, yet not so much as to cause the judge to set aside the findings.