CHAPTER 3

The Audit Process

This chapter discusses the following topics:

• Audit management

• ISACA auditing standards, procedures, and guidelines

• Audit and risk analysis

• Internal controls

• Performing an audit

The topics in this chapter represent 10 percent of the CISA examination.

The IS audit process is the procedural structure used by auditors to assess and evaluate the effectiveness of the IT organization and how well it supports the organization’s overall goals and objectives. The audit process is backed up by the framework that is the ISACA code of ethics, ISACA audit standards, guidelines, and audit procedures. This framework is used to ensure that auditors will take a consistent approach from one audit to the next throughout the entire industry. This will help to advance the entire audit profession and facilitate its gradual improvement over time.

Audit Management

An organization’s audit function should be managed so that an audit charter, strategy, and program can be established; audits performed; recommendations enacted; and auditor independence assured throughout. The audit function should align with the organization’s mission and goals, and work well alongside IT governance and operations.

The Audit Charter

As with any formal, managed function in the organization, the audit function should be defined and described in a charter document. The charter should clearly define roles and responsibilities that are consistent with ISACA audit standards and guidelines (including but not limited to ethics, integrity, and independence). The audit function should have sufficient authority that its recommendations will be respected and implemented, but not so much power that the audit tail will wag the IS dog.

The Audit Program

An audit program is the term used to describe the audit strategy and audit plans that include scope, objectives, resources, and procedures used to evaluate a set of controls and deliver an audit opinion. You could say that an audit program is the plan for conducting audits over a given period.

The term “program” in audit program is intended to evoke a similar “big picture” point of view as the term program manager does. A program manager is responsible for the performance of several related projects in an organization. Similarly, an audit program is the plan for conducting several audits in an organization.

Strategic Audit Planning

The purpose of audit planning is to determine the audit activities that need to take place in the future, including an estimate on the resources (budget and manpower) required to support those activities.

Factors that Affect an Audit

Like security planning, audit planning must take into account several factors:

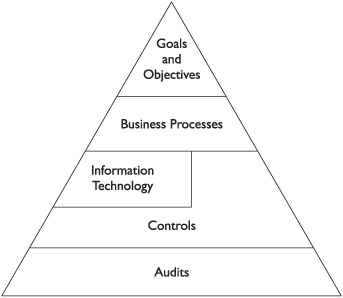

![]() Organization strategic goals and objectives The organization’s overall goals and objectives should flow down to individual departments and their support of these goals and objectives. These goals and objectives will translate into business processes, technology to support business processes, controls for both the business processes and technologies, and audits of those controls. This is depicted in Figure 3-1.

Organization strategic goals and objectives The organization’s overall goals and objectives should flow down to individual departments and their support of these goals and objectives. These goals and objectives will translate into business processes, technology to support business processes, controls for both the business processes and technologies, and audits of those controls. This is depicted in Figure 3-1.

![]() New organization initiatives Closely related to goals and objectives, organizations often embark on new initiatives, whether new products, new services, or new ways of delivering existing products and services.

New organization initiatives Closely related to goals and objectives, organizations often embark on new initiatives, whether new products, new services, or new ways of delivering existing products and services.

![]() Market conditions Changes in the product or service market may have an impact on auditing. For instance, in a product or services market where security is becoming more important, market competitors could decide to voluntarily undergo audits in order to show that their products or services are safer or better than the competition’s. Other market players may need to follow suit for competitive parity. Changes in the supply or demand of supply-chain goods or services can also affect auditing.

Market conditions Changes in the product or service market may have an impact on auditing. For instance, in a product or services market where security is becoming more important, market competitors could decide to voluntarily undergo audits in order to show that their products or services are safer or better than the competition’s. Other market players may need to follow suit for competitive parity. Changes in the supply or demand of supply-chain goods or services can also affect auditing.

![]() Changes in technology Enhancements in the technologies that support business processes may affect business or technical controls, which in turn may affect audit procedures for those controls.

Changes in technology Enhancements in the technologies that support business processes may affect business or technical controls, which in turn may affect audit procedures for those controls.

![]() Changes in regulatory requirements Changes in technologies, markets, or security-related events can result in new or changed regulations. Maintaining compliance may require changes to the audit program. In the 20-year period preceding the publication of this book, many new information security–related regulations have been passed or updated, including the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, as well as U.S. federal and state laws on privacy.

Changes in regulatory requirements Changes in technologies, markets, or security-related events can result in new or changed regulations. Maintaining compliance may require changes to the audit program. In the 20-year period preceding the publication of this book, many new information security–related regulations have been passed or updated, including the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, as well as U.S. federal and state laws on privacy.

Figure 3-1 Organization goals and objectives translate down into audit activities.

All of the changes listed here usually translate into new business processes or changes in existing business process. Often, this also involves changes to information systems and changes to the controls supporting systems and processes.

Changes in Audit Activities

These external factors may affect auditing in the following ways:

![]() New internal audits Business and regulatory changes sometimes compel organizations to audit more systems or processes. For instance, after passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, U.S. publicly traded companies had to begin conducting internal audits of those IT systems that support financial business processes.

New internal audits Business and regulatory changes sometimes compel organizations to audit more systems or processes. For instance, after passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, U.S. publicly traded companies had to begin conducting internal audits of those IT systems that support financial business processes.

![]() New external audits New regulations or competitive pressures could introduce new external audits. For example, virtually all banks and many merchants had to begin undergoing external PCI audits when that standard was established.

New external audits New regulations or competitive pressures could introduce new external audits. For example, virtually all banks and many merchants had to begin undergoing external PCI audits when that standard was established.

![]() Increase in audit scope The scope of existing internal or external audits could increase to include more processes or systems.

Increase in audit scope The scope of existing internal or external audits could increase to include more processes or systems.

![]() Impacts on business processes This could take the form of additional steps in processes or procedures, or additions/changes in recordkeeping or record retention.

Impacts on business processes This could take the form of additional steps in processes or procedures, or additions/changes in recordkeeping or record retention.

Resource Planning

At least once per year, management needs to consider all of the internal and external factors that affect auditing to determine the resources required to support these activities. Primarily, resources will consist of budget for external audits and manpower for internal audits.

Additional external audits usually require additional man-hours to meet with external auditors; discuss scope; coordinate meetings with process owners and managers; discuss audits with process owners and managers; discuss audit findings with auditors, process owners, and managers; and organize remediation work.

Internal and external audits usually require information systems to track audit activities and store evidence. Taking on additional audit activities may require additional capacity on these systems.

Additional internal audits require all of the previously mentioned factors, plus time for performing the internal audits themselves. All of these details are discussed in this chapter, and in the rest of this book.

Audit and Technology

ISACA auditing standards require that the auditor retain technical competence. With the continuation of technology and business process innovation, auditors need to continue learning about new technologies, how they support business processes, and how they are controlled. Like many professions, IS auditing requires continuing education to stay current with changes in technology.

Some of the ways that an IS auditor can update their knowledge and skills include:

![]() ISACA training and conferences As the developer of the CISA certification, ISACA offers many valuable training and conference events, including:

ISACA training and conferences As the developer of the CISA certification, ISACA offers many valuable training and conference events, including:

![]() Computer Audit, Control, and Security Conference (CACS)

Computer Audit, Control, and Security Conference (CACS)

![]() IT Governance, Risk, and Compliance Conference

IT Governance, Risk, and Compliance Conference

![]() Information Security and Risk Management Conference

Information Security and Risk Management Conference

![]() ISACA Training Week

ISACA Training Week

![]() University courses This can include both for-credit and noncredit classes on new technologies. Some universities offer certificate programs on many new technologies; this can give an auditor a real boost of knowledge, skills, and confidence.

University courses This can include both for-credit and noncredit classes on new technologies. Some universities offer certificate programs on many new technologies; this can give an auditor a real boost of knowledge, skills, and confidence.

![]() Voc-tech training Many organizations offer training in information technologies, including MIS Training Institute, SANS, Intense School, and ISACA.

Voc-tech training Many organizations offer training in information technologies, including MIS Training Institute, SANS, Intense School, and ISACA.

![]() Training webinars These events are usually focused on a single topic and last from one to three hours. ISACA and many other organizations offer training webinars, which are especially convenient since they require no travel and many are offered at no cost.

Training webinars These events are usually focused on a single topic and last from one to three hours. ISACA and many other organizations offer training webinars, which are especially convenient since they require no travel and many are offered at no cost.

![]() ISACA chapter training Many ISACA chapters offer regular training events so that local members can acquire new knowledge and skills where they live.

ISACA chapter training Many ISACA chapters offer regular training events so that local members can acquire new knowledge and skills where they live.

![]() Other security association training Many other security-related trade associations offer training, including ISSA (International Systems Security Association), SANS Institute (Systems administrations, Audit, Network, Security), and CSI (Computer Security Institute). Training sessions are offered online, in classrooms, and at conferences.

Other security association training Many other security-related trade associations offer training, including ISSA (International Systems Security Association), SANS Institute (Systems administrations, Audit, Network, Security), and CSI (Computer Security Institute). Training sessions are offered online, in classrooms, and at conferences.

![]() Security conferences Several security-related conferences include lectures and training. These conferences include RSA, SANS, CSI, ISSA, and SecureWorld Expo. Many local ISACA and ISSA chapters organize local conferences that include training.

Security conferences Several security-related conferences include lectures and training. These conferences include RSA, SANS, CSI, ISSA, and SecureWorld Expo. Many local ISACA and ISSA chapters organize local conferences that include training.

NOTE CISA certification holders are required to undergo at least 40 hours of training per year in order to maintain their certification. Chapter 1 contains more information on this requirement.

Audit Laws and Regulations

Laws and regulations are one of the primary reasons why organizations perform internal and external audits. Regulations on industries generally translate into additional effort on target companies’ parts to track their compliance. This tracking takes on the form of internal auditing, and new regulations sometimes also require external audits. And while other factors such as competitive pressures can compel an organization to begin or increase auditing activities, this section discusses laws and regulations that require auditing.

Almost every industry sector is subject to laws and regulations that affect organizations’ use of information systems. These laws are concerned primarily with one or more of the following characteristics and uses of information and information systems:

![]() Security Some information in information systems is valuable and/or sensitive, such as financial and medical records. Many laws and regulations require such information to be protected so that it cannot be accessed by unauthorized parties and that information systems be free of defects, vulnerabilities, malware, and other threats.

Security Some information in information systems is valuable and/or sensitive, such as financial and medical records. Many laws and regulations require such information to be protected so that it cannot be accessed by unauthorized parties and that information systems be free of defects, vulnerabilities, malware, and other threats.

![]() Integrity Some regulations are focused on the integrity of information to ensure that it is correct and that the systems it resides on are free of vulnerabilities and defects that could make or allow improper changes.

Integrity Some regulations are focused on the integrity of information to ensure that it is correct and that the systems it resides on are free of vulnerabilities and defects that could make or allow improper changes.

![]() Privacy Many information systems store information that is considered private. This includes financial records, medical records, and other information about people that they feel should be protected.

Privacy Many information systems store information that is considered private. This includes financial records, medical records, and other information about people that they feel should be protected.

Automation Brings New Regulation |

Automating business processes with information systems is still a relatively new phenomenon. Modern businesses have been around for the past two or three centuries, but information systems have been playing a major role in business process automation for only about the past 15 years. Prior to that time, most information systems supported business processes but only in an ancillary way. Automation of entire business processes is still relatively young, and so many organizations have messed up in such colossal ways that legislators and regulators have responded with additional laws and regulations to make organizations more accountable for the security and integrity of their information systems. |

Computer Security and Privacy Regulations

This section contains several computer security and privacy laws in the United States, Canada, Europe, and elsewhere. The laws here fall into one or more of the following categories:

![]() Computer trespass Some of these laws bring the concept of trespass forward into the realm of computers and networks, making it illegal to enter a computer or network unless there is explicit authorization.

Computer trespass Some of these laws bring the concept of trespass forward into the realm of computers and networks, making it illegal to enter a computer or network unless there is explicit authorization.

![]() Protection of sensitive information Many laws require that sensitive information be protected, and some include required public disclosures in the event of a breach of security.

Protection of sensitive information Many laws require that sensitive information be protected, and some include required public disclosures in the event of a breach of security.

![]() Collection and use of information Several laws define the boundaries regarding the collection and acceptable use of information, particularly private information.

Collection and use of information Several laws define the boundaries regarding the collection and acceptable use of information, particularly private information.

![]() Law enforcement investigative powers Some laws clarify and expand the search and investigative powers of law enforcement.

Law enforcement investigative powers Some laws clarify and expand the search and investigative powers of law enforcement.

The consequences of the failure to comply with these laws vary. Some laws have penalties written in as a part of the law; however, the absence of an explicit penalty doesn’t mean there aren’t any! Some of the results of failing to comply include:

![]() Loss of reputation Failure to comply with some laws can make front-page news, with a resulting reduction in reputation and loss of business. For example, if an organization suffers a security breach and is forced to notify customers, word may spread quickly and be picked up by news media outlets, which will help spread the news further.

Loss of reputation Failure to comply with some laws can make front-page news, with a resulting reduction in reputation and loss of business. For example, if an organization suffers a security breach and is forced to notify customers, word may spread quickly and be picked up by news media outlets, which will help spread the news further.

![]() Loss of competitive advantage An organization that has a reputation for sloppy security may begin to see its business diminish and move to its competitors. A record of noncompliance may also result in a failure to win new business contracts.

Loss of competitive advantage An organization that has a reputation for sloppy security may begin to see its business diminish and move to its competitors. A record of noncompliance may also result in a failure to win new business contracts.

![]() Government sanctions Breaking many federal laws may result in sanctions from local, regional, or national governments, including losing the right to conduct business.

Government sanctions Breaking many federal laws may result in sanctions from local, regional, or national governments, including losing the right to conduct business.

![]() Lawsuits Civil lawsuits from competitors, customers, suppliers, and government agencies may be the result of breaking some laws. Plaintiffs may file lawsuits against an organization even if there were other consequences.

Lawsuits Civil lawsuits from competitors, customers, suppliers, and government agencies may be the result of breaking some laws. Plaintiffs may file lawsuits against an organization even if there were other consequences.

![]() Fines Monetary consequences are frequently the result of breaking laws.

Fines Monetary consequences are frequently the result of breaking laws.

![]() Prosecution Many laws have criminalized behavior such as computer trespass, stealing information, or filing falsified reports to government agencies.

Prosecution Many laws have criminalized behavior such as computer trespass, stealing information, or filing falsified reports to government agencies.

Knowledge of these consequences provides an incentive to organizations to develop management strategies to comply with the laws that apply to their business activities. These strategies often result in the development of controls that define required activities and events, plus analysis and internal audit to determine if the controls are effectively keeping the organization in compliance with those laws. While organizations often initially resist undertaking these additional activities, they usually accept them as a requirement for doing business and seek ways of making them more cost-efficient in the long term.

Determining Compliance with Regulations An organization should take a systematic approach to determine the applicability of regulations as well as the steps required to attain compliance and remain in this state.

Determination of applicability often requires the assistance of legal counsel who is an expert on government regulations, as well as experts in the organization who are familiar with the organization’s practices.

Next, the language in the law or regulation needs to be analyzed and a list of compliant and noncompliant practices identified. These are then compared with the organization’s practices to determine which practices are compliant and which are not. Those practices that are not compliant need to be corrected; one or more accountable individuals need to be appointed to determine what is required to achieve and maintain compliance.

Another approach is to outline the required (or forbidden) practices specified in the law or regulation, and then “map” the organization’s relevant existing activities into the outline. Where gaps are found, processes or procedures will need to be developed to bring the organization into compliance.

Regulations Not Always Clear |

Sometimes, the effort to determine what’s needed to achieve compliance is substantial. For instance, when the Sarbanes-Oxley Act was signed into law, virtually no one knew exactly what companies had to do to achieve compliance. Guidance from the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board was not published for almost a year. It took another two years before audit firms and U.S. public companies were familiar and comfortable with the necessary approach to achieve compliance with the Act. |

U.S. Regulations Selected security and privacy laws and standards in the United States include:

![]() Access Device Fraud, 1984

Access Device Fraud, 1984

![]() Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1984

Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1984

![]() Electronic Communications Act of 1986

Electronic Communications Act of 1986

![]() Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) of 1986

Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) of 1986

![]() Computer Security Act of 1987

Computer Security Act of 1987

![]() Computer Matching and Privacy Protection Act of 1988

Computer Matching and Privacy Protection Act of 1988

![]() Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) of 1994

Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) of 1994

![]() Economic and Protection of Proprietary Information Act of 1996

Economic and Protection of Proprietary Information Act of 1996

![]() Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996

![]() Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998

![]() Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act of 1998

Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act of 1998

![]() Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) of 1999

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) of 1999

![]() Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

![]() Provide Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (PATRIOT) Act of 2001

Provide Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (PATRIOT) Act of 2001

![]() Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002

Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002

![]() Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) of 2002

Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) of 2002

![]() Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing (CAN-SPAM) Act of 2003

Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing (CAN-SPAM) Act of 2003

![]() California privacy law SB1386 of 2003

California privacy law SB1386 of 2003

![]() Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act of 2003

Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act of 2003

![]() Basel II, 2004

Basel II, 2004

![]() Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS), 2004

Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS), 2004

![]() North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), 1968/2006

North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), 1968/2006

![]() Massachusetts security breach law, 2007

Massachusetts security breach law, 2007

Canadian Regulations Selected security and privacy laws and standards in Canada include:

![]() Interception of Communications, Section 184

Interception of Communications, Section 184

![]() Unauthorized Use of Computer, Section 342.1

Unauthorized Use of Computer, Section 342.1

![]() Privacy Act, 1983

Privacy Act, 1983

![]() Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA)

Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA)

European Regulations Selected security and privacy laws and standards from Europe include:

![]() Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data, 1981, Council of Europe

Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data, 1981, Council of Europe

![]() Computer Misuse Act (CMA), 1990, UK

Computer Misuse Act (CMA), 1990, UK

![]() Directive on the Protection of Personal Data (95/46/EC), 2003, European Union

Directive on the Protection of Personal Data (95/46/EC), 2003, European Union

![]() Data Protection Act (DPA) 1998, UK

Data Protection Act (DPA) 1998, UK

![]() Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, UK

Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, UK

![]() Anti-Terrorism, Crime, and Security Act 2001, UK

Anti-Terrorism, Crime, and Security Act 2001, UK

![]() Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations 2003, UK

Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations 2003, UK

![]() Fraud Act 2006, UK

Fraud Act 2006, UK

![]() Police and Justice Act 2006, UK

Police and Justice Act 2006, UK

Other Regulations Selected security and privacy laws and standards from the rest of the world include:

![]() Cybercrime Act, 2001, Australia

Cybercrime Act, 2001, Australia

![]() Information Technology Act, 2000, India

Information Technology Act, 2000, India

ISACA Auditing Standards

The Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA) has published a code of ethics, a set of IS auditing standards, audit guidelines to help understand the standards, and procedures that can be used when auditing information systems. These are discussed in this section.

ISACA Code of Professional Ethics

Like many professional associations, ISACA has published a code of professional ethics. The purpose of the code is to define principles of professional behavior that are based on the support of standards, compliance with laws and standards, and the identification and defense of the truth.

Audit and IT professionals who earn the CISA certification are required to sign a statement that declares their support of the ISACA code of ethics. If someone who holds the CISA certification is found to be in violation of the code, he or she may be disciplined or lose his or her certification.

Members and ISACA Certification holders shall:

1. Support the implementation of, and encourage compliance with, appropriate standards, procedures and controls for information systems.

2. Perform their duties with due diligence and professional care, in accordance with professional standards and best practices.

3. Serve in the interest of stakeholders in a lawful and honest manner, while maintaining high standards of conduct and character, and not engage in acts discreditable to the profession.

4. Maintain the privacy and confidentiality of information obtained in the course of their duties unless disclosure is required by legal authority. Such information shall not be used for personal benefit or released to inappropriate parties.

5. Maintain competency in their respective fields and agree to undertake only those activities, which they can reasonably expect to complete with professional competence.

6. Inform appropriate parties of the results of work performed; revealing all significant facts known to them.

7. Support the professional education of stakeholders in enhancing their understanding of information systems security and control.

Failure to comply with this Code of Professional Ethics can result in an investigation into a member’s or certification holder’s conduct and, ultimately, in disciplinary measures.

NOTE The CISA candidate is not expected to memorize the ISACA code of ethics, but is required to understand and be familiar with it.

ISACA Audit Standards

The ISACA audit standards framework defines minimum standards of performance related to security, audits, and the actions that result from audits. This section lists the standards and discusses each.

The full text of these standards is available at www.isaca.org/standards.

S1, Audit Charter

Audit activities in an organization should be formally defined in an audit charter. This should include statements of scope, responsibility, and authority for conducting audits. Senior management should support the audit charter through direct signature or by linking the audit charter to corporate policy.

S2, Independence

Behavior of the IS auditor should be independent of the auditee. The IS auditor should take care to avoid even the appearance of impropriety.

The IS auditor’s placement in the command and control structure of the organization should ensure that the IS auditor can act independently.

S3, Professional Ethics and Standards

The IS auditor should adhere to the ISACA Code of Professional Ethics as well as other applicable standards. The IS auditor should conduct himself with professionalism and due care.

S4, Professional Competence

The IS auditor should possess all of the necessary skills and knowledge that are related to the processes and technologies being audited. The auditor should receive periodic training and continuing education in the practices and technologies that are related to her work.

S5, Planning

The IS auditor should perform audit planning work to ensure that the scope and breadth of auditing is sufficient to meet the organization’s needs. She should develop and maintain documentation related to a risk-based audit process and audit procedures. The auditor should identify applicable laws and develop plans for any required audit activities to ensure compliance.

S6, Performance of Audit Work

IS auditors should be supervised to ensure that their work supports established audit objectives and meets applicable audit standards. IS auditors should obtain and retain appropriate evidence; auditors’ findings should reflect analysis and the evidence obtained. The process followed for each audit should be documented and made a part of the audit report.

S7, Reporting

The IS auditor should develop an audit report that documents the process followed, inquiries, observations, evidence, findings, conclusions, and recommendations from the audit. The audit report should follow an established format that includes a statement of scope, period of coverage, recipient organization, controls or standards that were audited, and any limitations or qualifications. The report should contain sufficient evidence to support the findings of the audit.

S8, Follow-up Activities

After the completion of an audit, the IS auditor should follow up at a later time to determine if management has taken steps to make any recommended changes or apply remedies to any audit findings.

S9, Irregularities and Illegal Acts

IS auditors should have a healthy but balanced skepticism with regard to irregularities and illegal acts: The auditor should recognize that irregularities and/or illegal acts could be ongoing in one or more of the processes that he is auditing. He should recognize that management may or may not be aware of any irregularities or illegal acts.

The IS auditor should obtain written attestations from management that state management’s responsibilities for the proper operation of controls. Management should disclose to the auditor any knowledge of irregularities or illegal acts.

If the IS auditor encounters material irregularities or illegal acts, he should document every conversation and retain all evidence of correspondence. The IS auditor should report any matter of material irregularities or illegal acts to management. If material findings or irregularities prevent the auditor from continuing the audit, the auditor should carefully weigh his options and consider withdrawing from the audit. The IS auditor should determine if he is required to report material findings to regulators or other outside authorities. If the auditor is unable to report material findings to management, he should consider withdrawing from the audit engagement.

S10, IT Governance

The IS auditor should determine if the IT organization supports the organization’s mission, goals, objectives, and strategies. This should include whether the organization had clear expectations of performance from the IT department.

The auditor should determine if the IT organization is compliant with all applicable policies, laws, regulations, and contractual obligations. She should use a risk-based approach when evaluating the IT organization.

The IS auditor should determine if the control environment used in the IT organization is effective and should identify risks that may adversely affect IT department operations.

S11, Use of Risk Assessment in Audit Planning

The IS auditor should use a risk-based approach when making decisions about which controls and activities should be audited and the level of effort expended in each audit. These decisions should be documented in detail to avoid any appearance of partiality.

A risk-based approach does not look only at security risks, but overall business risk. This will probably include operational risk and may include aspects of financial risk.

S12, Audit Materiality

The IS auditor should consider materiality when prioritizing audit activities and allocating audit resources. During audit planning, the auditor should consider whether ineffective controls or an absence of controls could result in a significant deficiency or material weakness.

In addition to auditing individual controls, the auditor should consider the effectiveness of groups of controls and determine if a failure across a group of controls would constitute a significant deficiency or material weakness. For example, if an organization has several controls regarding the management and control of third-party service organizations, failures in many of those controls could represent a significant deficiency or material weakness overall.

S13, Use the Work of Other Experts

An IS auditor should consider using the work of other auditors, when and where appropriate. Whether an auditor can use the work of other auditors depends on several factors, including:

![]() The relevance of the other auditors’ work

The relevance of the other auditors’ work

![]() The qualifications and independence of the other auditors

The qualifications and independence of the other auditors

![]() Whether the other auditors’ work is adequate (this will require an evaluation of at least some of the other auditors’ work)

Whether the other auditors’ work is adequate (this will require an evaluation of at least some of the other auditors’ work)

![]() Whether the IS auditor should develop additional test procedures to supplement the work of another auditor(s)

Whether the IS auditor should develop additional test procedures to supplement the work of another auditor(s)

If an IS auditor uses another auditor’s work, his report should document which portion of the audit work was performed by the other auditor, as well as an evaluation of that work.

S14, Audit Evidence

The IS auditor should gather sufficient evidence to develop reasonable conclusions about the effectiveness of controls and procedures. The sufficiency and integrity of audit evidence should be evaluated, and this evaluation should be included in the audit report.

Audit evidence includes the procedures performed by the auditor during the audit, the results of those procedures, source documents and records, and corroborating information. Audit evidence also includes the audit report.

ISACA Audit Guidelines

ISACA audit guidelines contain information that helps the auditor understand how to apply ISACA audit standards. These guidelines are a series of articles that clarify the meaning of the audit standards. They cite specific ISACA IS audit standards and COBIT controls, and provide specific guidance on various audit activities. ISACA audit guidelines also provide insight into why each guideline was developed and published.

The full text of these guidelines is available at www.isaca.org/standards.

G1, Using the Work of Other Auditors

Written June 1998, updated March 2008. Clarifies Standard S13, Using the Work of Other Experts, and Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

Explores details regarding using the work of other auditors, including assessing their qualifications, independence, relevance, and the level of review required.

G2, Audit Evidence Requirement

Written December 1998, updated May 2008. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work, Standard S9, Irregularities and Illegal Acts, Standard S13, Using the Work of Other Experts, and Standard S14, Audit Evidence.

Provides additional details regarding types of evidence, how evidence can be represented, and selecting and gathering evidence.

G3, Use of Computer-Assisted Audit Techniques (CAATs)

Written December 1998, updated March 2008. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work, Standard S5, Planning, Standard S3, Professional Ethics and Standards, Standard S7, Reporting, and Standard S14, Audit Evidence.

Provides details on the use of CAATs, whose use is increasing. In some information systems, CAATs provide the majority of available evidence. This guideline provides direction on the reliability of CAAT-based evidence, automated and customized test scripts, software tracing and mapping, expert systems, and continuous monitoring.

G4, Outsourcing of IS Activities to Other Organizations

Written September 1999, updated May 2008. Clarifies Standard S1, Audit Charter, Standard S5, Planning, and Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

Includes additional granularity for auditing outsourced IS activities, including examination of legal contracts and SLAs and service management.

G5, Audit Charter

Written September 1999, updated February 2008. Clarifies Standard S1, Audit Charter.

Guidance provides additional weight on the need for an audit mandate and additional details on the contents of an audit charter, including purpose, responsibilities, authority, accountability, communication with auditees, and quality assurance. Also includes details on the contents of an engagement letter.

G6, Materiality Concepts for Auditing Information Systems

Written September 1999, updated May 2008. Clarifies Standard S5, Planning, Standard S10, IT Governance, Standard S12, Audit Materiality, and Standard S9, Irregularities and Illegal Acts.

While financial audits can easily focus on materiality, IS audits focus on other topics such as access controls and change management. This guidance includes information on how to determine materiality of audits of IS controls.

G7, Due Professional Care

Written September 1999, updated March 2008. Clarifies Standard S2, Independence, Standard S3, Professional Ethics and Standards, and Standard S4, Professional Competence.

This provides guidance to IS auditors for applying auditing standards and the ISACA Code of Professional Ethics on performance of duties with due diligence and professional care. This guidance helps the IS auditor better understand how to have good professional judgment in difficult situations.

G8, Audit Documentation

Written September 1999, updated March 2008. Clarifies Standard S5, Planning, Standard S6 Performance of Audit Work, Standard S7 Reporting, Standard S12, Audit Materiality, and Standard S13, Using the Work of Other Experts.

This guideline provides considerably more detail on the specific documentation needs for an IS audit. This includes providing additional information regarding the auditor’s assessment methods and retention of audit documents.

G9, Audit Considerations for Irregularities and Illegal Acts

Written March 2000, updated September 2008. Clarifies Standard S3, Professional Ethics and Standards, Standard S5, Planning, Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work, Standard S7, Reporting, and Standard S9, Irregularities and Illegal Acts.

This guideline adds more color to ISACA audit standards for situations that the IS auditor may encounter, including nonfraudulent irregularities, fraud, and illegal acts. The guideline defines additional responsibilities of management and IS auditors when dealing with irregularities and illegal acts.

The guideline also describes the steps in a risk assessment that includes the identification of risks that are related to irregularities and illegal acts. Next, the guideline details the actions that an IS auditor should follow when encountering illegal acts, including internal and external reporting where required by law.

G10, Audit Sampling

Written March 2000, updated August 2008. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This provides guidance on objective, statistically sound sampling techniques, sample design and selection, and evaluation of the sample selection.

G11, Effect of Pervasive IS Controls

Written March 2000, updated August 2008. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

Pervasive controls are those general controls that focus on the management and monitoring of information systems. Examples of pervasive controls are:

![]() IS strategy

IS strategy

![]() Software development/acquisition life cycle

Software development/acquisition life cycle

![]() Access management

Access management

![]() Security administration

Security administration

![]() Capacity management

Capacity management

![]() Backup and recovery

Backup and recovery

This guideline helps the auditor understand the pervasive controls that should be a part of every organization’s control framework. The IS auditor needs to determine the set of pervasive controls in her organization—they can be derived from the four COBIT domains: Plan and Organize (PO), Acquire and Implement (AI), Deliver and Support (DS), and Monitor and Evaluate (ME). It is no accident that these match up to the Deming Cycle process of Plan, Do, Check, Act.

G12, Organizational Relationship and Independence

Written September 2000, updated August 2008. Clarifies Standard S2, Independence, and Standard S3, Professional Ethics and Standards.

This guideline expands on the concept and practice of auditor independence so that the auditor can better understand how to apply audit standards and perform audits objectively and independently.

G13, Use of Risk Assessment in Audit Planning

Written September 2000, updated August 2008. Clarifies Standard S5, Planning, and Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline provides direction for the IS auditor to properly determine the risk associated with each control and related activity in the IS organization. Such guidance has been available for financial auditors, but was not readily available to IS auditors until publication of this guideline.

Rather than rely solely on judgment, IS auditors need to use a systematic and consistent approach to establishing the level of risk. The chosen approach should be used as a key input in audit planning.

G14, Application Systems Review

Written November 2001, updated December 2008. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline provides additional information for IS auditors who are performing an application systems review. The purpose of such a review is to identify application risks and evaluate an application’s controls to determine how effectively the application supports the organization’s overall controls and objectives.

G15, Planning

Written March 2002. Clarifies Standard S5, Planning.

This guideline assists the IS auditor in the development of a plan for an audit project by providing additional information found in ISACA audit standard S5. An audit plan needs to take several matters into consideration, including overall business requirements, the objectives of the audit, and knowledge about the organization’s processes and information systems. Levels of materiality should be established and a risk assessment performed, if necessary.

G16, Effect of Third Parties on an Organization’s IT Controls

Written March 2002, updated March 2009. Clarifies Standard S5, Planning, and Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

Third-party organizations can become a key component in one or more controls. In situations where an organization outsources key business applications, the third party’s controls for practical purposes supplement the organization’s own controls.

The IS auditor needs to understand how a third-party organization supports the organization’s business objectives. This may require a review of contracts, service level agreements, and other business documents that describe the services that the third-party organization provides.

The auditor will need to review the third party’s controls through reviews of independent audits of another third-party organization. The IS auditor also needs to understand the effects and the risks associated with the use of the third party, and be able to identify countermeasures or compensating controls that will minimize risk.

G17, Effect of Nonaudit Role on the IS Auditor’s Independence

Written July 2002, updated June 2009. Clarifies Standard S2, Independence, and Standard S3, Professional Ethics and Standards.

In many organizations, IS auditors are involved in many nonaudit activities, including security strategy development, implementation of information technologies, software design, development and integration, process development, and implementing security controls. These activities provide additional knowledge and experience, which help the IS auditor better understand how security and technology support the organization. However, some of these activities may adversely affect the IS auditor’s independence and objectivity.

G18, IT Governance

Written July 2002. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

Organizations have created a critical dependency upon information technology to conduct business transactions. The role of IT systems is critical to an organization’s goals and objectives. This trend has made IT governance all the more critical to an organization’s success. IS auditors need to have a clear understanding of the role of IT governance when planning and carrying out an audit.

G19, Irregularities and Illegal Acts

This guideline was replaced in September 2008 by Guideline G9, Audit Considerations for Irregularities and Illegal Acts.

G20, Reporting

Written January 2003. Clarifies Standard S7, Reporting.

This guideline describes how an IS auditor should comply with ISACA auditing standards on the development of audit findings, audit opinion, and audit report.

G21, Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Systems Review

Written August 2003.

This guideline provides additional information for the IS auditor who is performing a review or audit of enterprise resource planning (ERP) applications and systems. The guideline describes ERP systems and business process reengineering (BPR), and provides considerable detail of audit procedures.

G22, Business-to-Consumer (B2C) E-commerce Review

Written August 2003, updated December 2008. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline provides additional information for the IS auditor who may be performing a review or audit of a business-to-consumer e-commerce application or system. The guideline defines and describes e-commerce systems and describes several areas that should be the focus of an audit. The guideline includes a detailed audit plan and areas of possible risk.

G23, System Development Life Cycle (SDLC) Review

Written August 2003. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline provides IS auditors with additional information regarding audits of the process of defining, acquiring, and implementing applications. This process is commonly known as the systems development life cycle (SDLC).

G24, Internet Banking

Written August 2003. Clarifies Standard S2, Independence, Standard S4, Professional Competence, Standard S5, Planning, and Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline provides IS auditors with detailed information regarding the review and audit of Internet banking applications. The guideline describes Internet banking and includes detailed audit procedures.

G25, Review of Virtual Private Networks

Written July 2004. Clarifies S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline describes virtual private network (VPN) technology and architecture, and provides detailed audit procedures. The guideline includes a description of VPN-related risks.

G26, Business Process Reengineering (BPR) Project Reviews

Written July 2004. Clarifies S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline describes the process of business process reengineering (BPR) and the potentially profound effect it can have on organizational effectiveness. The guideline describes operational risks associated with BPR and includes audit guidelines for BPR projects and their impact on business processes, information systems, and corporate structures.

G27, Mobile Computing

Written September 2004. Clarifies Standard S1, Audit Charter, Standard S4, Professional Competence, Standard S5, Planning, and Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline describes the phenomenon of mobile computing in business operations, the technologies that support mobile computing, the risks associated with mobile computing, and guidance on applying audit standards on mobile computing infrastructures.

G28, Computer Forensics

Written September 2004. Clarifies Standard S3, Professional Ethics and Standards, Standard S4, Professional Competence, Standard S5, Planning, and Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

Because of their expertise in security and controls, IS auditors are subject to being asked to assist with investigations of irregularities, fraud, and criminal acts. This guideline defines forensics terms and includes forensics procedures that should be followed in such proceedings.

G29, Post-implementation Review

Written January 2005. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work, and Standard S8, Follow-up Activities.

This guideline includes recommended practices for carrying out a post-implementation review of a new or updated information system. The purpose of a post-implementation review is to measure the effectiveness of the new system.

G30, Competence

Written June 2005. Clarifies Standard S4, Professional Competence.

This guideline provides additional details on the need for an IS auditor to attain and maintain knowledge and skills that are relevant to IS auditing and information technologies in use.

G31, Privacy

Written June 2005. Clarifies Standard S1, Audit Charter, Standard S5, Planning, and Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline provides additional information about privacy so that the IS auditor can properly consider privacy requirements, concerns, and laws during IS audits. The guideline includes details on the approach for personal data protection.

G32, Business Continuity Plan (BCP) Review from IT Perspective

Written September 2005. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline provides recommended practices for the review of business continuity plans and testing of BCP controls. It includes a description of business continuity planning, disaster recovery planning (DRP), and business impact analysis (BIA).

G33, General Considerations on the Use of the Internet

Written March 2006. Clarifies Standard S4, Professional Competence, Standard S5, Planning, and Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline provides detailed information for the IS auditor regarding the use of the Internet in support of business information systems. It includes a description of risks and audit procedures for evaluating controls that include the use of Internet-based resources.

G34, Responsibility, Authority, and Accountability

Written March 2006. Clarifies Standard S1, Audit Charter.

This guideline updates the responsibility, authority, and accountability of IS auditors in light of the advancements in technology and the pervasive use of information technology in support of critical business processes in the time since Standard S1 was originally written.

G35, Follow-up Activities

Written March 2006. Clarifies Standard S8, Follow-up Activities.

This guideline provides additional direction to IS auditors with regard to follow-up activities after an IS audit.

G36, Biometric Controls

Written February 2007. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work, and Standard S10, IT Governance.

This guideline provides additional information about biometric technology, including guidance on reviewing and auditing such technology.

G37, Configuration Management

Written November 2007. Clarifies Standard S6, Performance of Audit Work.

This guideline provides information about auditing configuration management tools and processes, and whether they are effective at making an organization’s IT environment more efficient and stable.

G38, Access Controls

Written February 2008. Clarifies Standard S1, Audit Charter, and Standard S3, Professional Ethics and Standards.

This guideline provides additional guidance on the audit of access controls and how they protect an organization’s assets from disclosure and abuse.

G39, IT Organization

Written May 2008. Clarifies Standard S10, IT Governance.

This guideline provides additional information to the IS auditor regarding the audit and review of IT governance. It describes the common themes that exist among most IT organizations, as well as the typical differences between them. This information can assist an IS auditor by describing the common attributes of IT organizations.

G40, Review of Security Management Practices

Written December 2008. Clarifies Standard S1, Audit Charter, and Standard S3, Professional Ethics and Standards.

This guideline provides additional guidance to IS auditors who are reviewing and auditing an organization’s security management practices. Information is a key asset in many organizations, and the protection of that information is vital to the organization’s survival. Security management provides the framework for that protection.

ISACA Audit Procedures

ISACA audit procedures contain information that helps the auditor understand how to audit different types of technologies and processes. While auditors are not required to follow these procedures, they provide insight into how technologies and processes can be audited effectively.

The full text of these procedures is available at www.isaca.org/standards.

P1, Risk Assessment

Written July 2002.

This procedure defines the IS audit risk assessment as a methodology used to optimize the allocation of IS audit resources through an understanding of the organization’s IS environment and the risks associated with each aspect or component in the environment. In other words, it is a method for identifying where the highest risks are so that IS auditors can concentrate their audit activities on those areas.

The procedure describes a detailed scoring-based methodology that can be used to objectively identify areas of highest risk. It includes several example risk assessments to illustrate the methodology in action. The examples include listings of risk factors, weighting, and scoring to arrive at a total risk ranking for components in the environment.

P2, Digital Signature and Key Management

Written July 2002.

This procedure describes the evaluation of a certificate authority (CA) business function. It defines key terms and includes detailed checklists on the key characteristics of a CA that must be examined in an audit. The procedure considers business attributes, technology and its management, and whether the CA has had any prior audits. The areas examined are organizational management, certification and accreditation, technology architecture, and operations management. Each area includes a checklist of procedures to be completed by the auditor.

P3, Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) Review Procedure

Written August 2003.

This procedure describes the function of an intrusion detection system, its purpose, and benefits. Both host-based and network-based IDS systems are described in detail. The procedure includes a detailed list of attributes to examine during an audit.

P4, Viruses and Other Malicious Code

Written August 2003.

This is a detailed procedure for assessing an organization’s antivirus and anti-mal-ware business and technical controls. Also included is a procedure for end users to follow if they suspect a malware infection on their workstation.

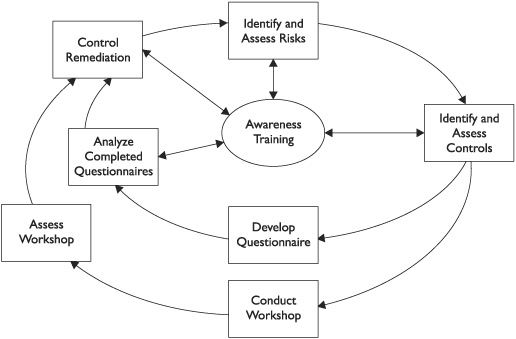

P5, Control Risk Self-Assessment

Written August 2003.

This is a detailed control risk self-assessment (CRSA) procedure. This is a process that is used to identify risks and mitigate them through the implementation of controls. While a CRSA is not a substitute for an external audit, it does help the organization focus inward, identify risk areas, and develop solutions to reduce risk. This helps an organization take responsibility for identifying and mitigating areas of risk.

P6, Firewalls

Written August 2003.

This procedure includes a detailed description of the types of firewalls, how they function, and how they are configured. Also covered are detailed descriptions of network address translation (NAT), virtual private networks (VPNs), and network architecture that is related to firewalls. The procedure also includes detailed steps to audit a firewall, including its configuration and its operation.

P7, Irregularities and Illegal Acts

Written November 2003.

This audit procedure helps the IS auditor assess the likelihood that irregularities could occur in business processes. Irregularities could include errors, illegal acts, and fraud. This procedure contains a detailed list of analytical procedures and computer-assisted audit procedures that can detect irregularities. It contains examples of irregularities and procedures for reporting irregularities, or conditions that could permit them.

P8, Security Assessment—Penetration Testing and Vulnerability Analysis

Written September 2004.

This procedure document contains detailed information for IS auditors and other security professionals who are responsible for performing penetration tests and vulnerability analyses. The procedure includes detailed discussions and checklists for external penetration testing, internal penetration testing, tests of physical access controls, social engineering, wireless network assessments, war dialing, manual and automated scans of web-based applications, and vulnerability assessments. The procedure also contains guidance on report preparation.

P9, Evaluation of Management Controls over Encryption Methodologies

Written January 2005.

This procedure contains a thorough description of encryption technology, including discussions of symmetric key cryptography, public key cryptography, and one-way hashing. The procedure includes risk assessment on the use of encryption, a discussion on the common uses and applications of encryption, laws and regulations on the use of encryption, and a detailed audit procedure.

P10, Business Application Change Control

Written October 2006.

This procedure describes and details the purpose and phases of the systems development life cycle (SDLC) and includes detailed procedures for auditing change control procedures.

P11, Electronic Funds Transfer

Written May 2007.

This procedure describes the electronic funds transfer (EFT) system in detail and includes an EFT risk assessment and detailed audit procedures.

Relationship Between Standards, Guidelines, and Procedures |

The ISACA audit standards, guidelines, and procedures have all been written to assist IS auditors with audit- and risk-related activities. They are related to each other in this way: |

|

|

|

Risk Analysis

In the context of an audit, risk analysis is the activity that is used to determine the areas that warrant additional examination and analysis.

In the absence of a risk analysis, an IS auditor is likely to follow his or her “gut instinct” and apply additional scrutiny in areas where they feel risks are higher. Or, an IS auditor might give all areas of an audit equal weighting, putting equal resources into low-risk areas and high-risk areas. Either way, the result is that an IS auditor’s focus is not necessarily on the areas where risks really are higher.

Auditors’ Risk Analysis and the Corporate Risk Management Program

A risk analysis that is carried out by IS auditors is distinct and separate from risk analysis that is performed as part of the IS risk management program. Often, these are carried out by different personnel and for somewhat differing reasons. A comparison of IS auditor and IS management risk analysis is shown in Table 3-1.

In Table 3-1, I am not attempting to show a polarity of focus and results, but instead a tendency for focus based on the differing missions and objectives for IS audit and IS management.

Evaluating Business Processes

The first phase of a risk analysis is an evaluation of business processes. The purpose of evaluating business processes is to determine the purpose and importance of business activities. While a risk analysis may focus on technology, remember that technology exists to support business processes, not the other way around.

Table 3-1 Comparison of IS Audit and IS Management Risk Analysis

When a risk analysis starts with a focus on business processes, it is possible to consider the entire process and not just the technology that supports it. When examining business processes, it is important to obtain all available business process documentation, including:

![]() Charter or mission statement Often, an organization will develop and publish a high-level document that describes the process in its most basic terms. This usually includes the reason that the process exists and how it contributes to the organization’s overall goals and objectives.

Charter or mission statement Often, an organization will develop and publish a high-level document that describes the process in its most basic terms. This usually includes the reason that the process exists and how it contributes to the organization’s overall goals and objectives.

![]() Process architecture A complex process may have several procedures, flows of information (whether in electronic form or otherwise), internal and external parties that perform functions, assets that support the process, and the locations and nature of records. In a strictly IT-centric perspective, this would be a data flow diagram or an entity-relationship diagram, but starting with either of those would be too narrow a focus. Instead, it is necessary to look at the entire process, with the widest view of its functions and connections with other processes and parties.

Process architecture A complex process may have several procedures, flows of information (whether in electronic form or otherwise), internal and external parties that perform functions, assets that support the process, and the locations and nature of records. In a strictly IT-centric perspective, this would be a data flow diagram or an entity-relationship diagram, but starting with either of those would be too narrow a focus. Instead, it is necessary to look at the entire process, with the widest view of its functions and connections with other processes and parties.

![]() Procedures Looking closer at the process will reveal individual procedures—documents that describe the individual steps taken to perform activities that are part of the overall process. Procedure documents usually describe who (if not by name, then by title or department) performs what functions with what tools or systems. Procedures will cite business records that might be faxes, reports, databases, phone records, application transactions, and so on.

Procedures Looking closer at the process will reveal individual procedures—documents that describe the individual steps taken to perform activities that are part of the overall process. Procedure documents usually describe who (if not by name, then by title or department) performs what functions with what tools or systems. Procedures will cite business records that might be faxes, reports, databases, phone records, application transactions, and so on.

![]() Records Business records contain the events that take place within a business process. Records will take many forms, including faxes, computer reports, electronic worksheets, database transactions, receipts, canceled checks, and e-mail messages.

Records Business records contain the events that take place within a business process. Records will take many forms, including faxes, computer reports, electronic worksheets, database transactions, receipts, canceled checks, and e-mail messages.

![]() Information system support When processes are supported by information systems, it is necessary to examine all available documents that describe information systems that support business processes. Examples of documentation are architecture diagrams, requirements documents (which were used to build, acquire, or configure the system), computer-run procedures, network diagrams, database schemas, and so on.

Information system support When processes are supported by information systems, it is necessary to examine all available documents that describe information systems that support business processes. Examples of documentation are architecture diagrams, requirements documents (which were used to build, acquire, or configure the system), computer-run procedures, network diagrams, database schemas, and so on.

Once the IS auditor has obtained business documents and records, she can begin to identify and understand any risk areas that may exist in the process.

Identifying Business Risks

The process of identifying business risks is partly analytical and partly based on the auditor’s experience and judgment. An auditor will usually consider both within the single activity of risk identification.

An auditor will usually perform a threat analysis to identify and catalog risks. A threat analysis is an activity whereby the auditor considers a large body of possible threats and selects those that have some reasonable possibility of occurrence, however small. In a threat analysis, the auditor will consider each threat and document a number of facts about each, including:

![]() Probability of occurrence This may be expressed in qualitative (high, medium, low) or quantitative (percentage or number of times per year, for example) terms. The probability should be as realistic as possible, recognizing the fact that actuarial data on business risk is difficult to obtain and more difficult to interpret. Here, an auditor’s judgment is required to establish a reasonable probability.

Probability of occurrence This may be expressed in qualitative (high, medium, low) or quantitative (percentage or number of times per year, for example) terms. The probability should be as realistic as possible, recognizing the fact that actuarial data on business risk is difficult to obtain and more difficult to interpret. Here, an auditor’s judgment is required to establish a reasonable probability.

![]() Impact This is a short description of the results if the threat is actually realized. This is usually a short description, from a few words to a couple of sentences.

Impact This is a short description of the results if the threat is actually realized. This is usually a short description, from a few words to a couple of sentences.

![]() Loss This is usually a quantified and estimated loss should the threat actually occur. This figure might be a loss of revenue per day (or week or month) or the replacement cost for an asset, for example.

Loss This is usually a quantified and estimated loss should the threat actually occur. This figure might be a loss of revenue per day (or week or month) or the replacement cost for an asset, for example.

![]() Possible mitigating controls This is a list of one or more countermeasures that can reduce the probability or the impact of a threat, or both.

Possible mitigating controls This is a list of one or more countermeasures that can reduce the probability or the impact of a threat, or both.

![]() Countermeasure cost and effort The cost and effort to implement each countermeasure should be identified, either with a high-medium-low qualitative figure or a quantitative estimate.

Countermeasure cost and effort The cost and effort to implement each countermeasure should be identified, either with a high-medium-low qualitative figure or a quantitative estimate.

![]() Updated probability of occurrence With each mitigating control, a new probability of occurrence should be cited. A different probability, one for each mitigating control, should be specified.

Updated probability of occurrence With each mitigating control, a new probability of occurrence should be cited. A different probability, one for each mitigating control, should be specified.

![]() Updated impact With each mitigating control, a new impact of occurrence should be described. For certain threats and countermeasures, the impact may be the same, but for some threats, it may be different. For example, for a threat of fire, a mitigating control may be an inert gas fire suppression system. The new impact (probably just downtime and cleanup) will be much different from the original impact (probably water damage from a sprinkler system).

Updated impact With each mitigating control, a new impact of occurrence should be described. For certain threats and countermeasures, the impact may be the same, but for some threats, it may be different. For example, for a threat of fire, a mitigating control may be an inert gas fire suppression system. The new impact (probably just downtime and cleanup) will be much different from the original impact (probably water damage from a sprinkler system).

The auditor will put all of this information into a chart (or electronic spreadsheet) to permit further analysis and the establishment of conclusions—primarily, which threats are the most likely to occur and which ones have the greatest potential impact on the organization.

NOTE The risk analysis method described here is no different from the risk analysis that takes place during the business impact assessment phase in a disaster recovery project, covered in Chapter 7.

NOTE The establishment of a list of threats, along with their probability of occurrence and impact, depends heavily on the experience of the IS auditor and the resources available to him.

Risk Mitigation

The actual mitigation of risks identified in the risk assessment is the implementation of one or more of the countermeasures found in the risk assessment. In simple terms, mitigation could be as easy as a small adjustment in a process or procedure, or a major project to introduce new controls in the form of system upgrades, new components, or new procedures.

When the IS auditor is conducting a risk analysis prior to an audit, risk mitigation may take the form of additional audit scrutiny on certain activities during the audit. An area that the auditor identified as high risk could end up performing well, while other lower-risk areas could actually be the cause of control failures.

Additional audit scrutiny could take several forms, including:

![]() More time spent in inquiry and observation

More time spent in inquiry and observation

![]() More personnel interviews

More personnel interviews

![]() Higher sampling rates

Higher sampling rates

![]() Additional tests

Additional tests

![]() Reperformance of some control activities to confirm accuracy or completeness

Reperformance of some control activities to confirm accuracy or completeness

![]() Corroboration interviews

Corroboration interviews

Countermeasures Assessment

Depending upon the severity of the risk, mitigation could also take the form of additional (or improved) controls, even prior to (or despite the results of) the audit itself. The new or changed control may be major or minor, and the time and effort required to implement it could range from almost trivial to a major project.

The cost and effort required to implement a new control (or whatever the countermeasure is that is designed to reduce the probability or impact of a threat) should be determined before it is implemented. It probably does not make sense to spend $10,000 to protect an asset worth $100.

NOTE The effort required to implement a control countermeasure should be commensurate with the level of risk reduction expected from the countermeasure. A quantified risk analysis may be needed if the cost and effort seem high, especially when compared to the value of the asset being protected.

Monitoring

After countermeasures are implemented, the IS auditor will need to reassess the controls through additional testing. If the control includes any self-monitoring or measuring, the IS auditor should examine those records to see if there is any visible effect of the countermeasures.

The auditor may need to reperform audit activities to determine the effectiveness of countermeasures. For example, additional samples selected after the countermeasure is implemented can be examined and the rate of exceptions compared to periods prior to the countermeasure’s implementation.

Internal Controls

The policies, procedures, mechanisms, systems, and other measures designed to reduce risk are known as internal controls. An organization develops controls to ensure that its business objectives will be met, risks will be reduced, and errors will be prevented or corrected.

Controls are used in two primary ways in an organization: They are created to achieve desired events, and they are created to avoid unwanted events.

Control Classification

Several types, classes, and categories of controls are discussed in this section. Figure 3-2 depicts this control classification.

Types of Controls

The three types of controls are physical, technical, and administrative.

![]() Physical These types of controls exist in the tangible, physical world. Examples of physical controls are video surveillance, bollards, and fences.

Physical These types of controls exist in the tangible, physical world. Examples of physical controls are video surveillance, bollards, and fences.

![]() Technical These controls are implemented in the form of information systems and are usually intangible. Examples of technical controls include encryption, computer access controls, and audit logs.

Technical These controls are implemented in the form of information systems and are usually intangible. Examples of technical controls include encryption, computer access controls, and audit logs.

![]() Administrative These controls are the policies and procedures that require or forbid certain activities. An example administrative control is a policy that forbids personal use of information systems.