by Richard Frost and Tom Keuten

Information Systems & Services (IS&S) is the global information technology (IT) organization for General Motors (GM). IS&S is focused on partnering with GM’s business units to drive innovation and efficiency throughout the global GM enterprise. To accomplish this, IS&S determined the need to develop a new global sourcing structure and drive simplification, standardization, and collaboration among and with its supplier network. When designing its new global sourcing structure, GM approached the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) for guidance and best practices applicable to companies that manage suppliers. The two organizations jointly realized that the current maturity models were focused on development—not acquisition—and the IT industry was looking for a model to help acquirers. Together, they partnered with industry and government leaders from around the globe to create the CMMI for Acquisition (CMMI-ACQ) model. GM became an early adopter of the CMMI-ACQ model and used it as a framework to help benchmark its organization and processes as it moved a new global model of IT sourcing with suppliers.

GM used the CMMI-ACQ model to identify the key competencies that IS&S must retain in this environment in which all IT development and support is sourced. Within GM, the IS&S department is recognized as the strategic hub of IT (see Figure 7.1). The IS&S staff does not create or operate systems; instead, it develops deep knowledge of GM’s business processes and develops enterprise and systems engineering architectures for those processes. IS&S then brokers relationships with suppliers to build, operate, and secure systems.

In this role, the IS&S organization strategically builds competencies in business requirements (to maintain knowledge of the business), systems engineering (to drive technology standards and target architectures), and project management (to ensure successful system delivery). These core competencies correspond directly to process areas in the CMMI-ACQ model. GM also uses all of the other practices in the CMMI-ACQ model to help IS&S further define the system delivery processes and drive acquisition maturity across the organization.

Prior to the creation of the CMMI-ACQ model, IS&S successfully used the CMMI for Development (CMMI-DEV) model to standardize processes globally. As the organization matured in its acquisition capabilities, it realized that the practices for a customer, or acquirer, of technology are substantially different from the practices of development organizations. With this insight, GM now uses CMMI-ACQ as a model for its processes as a customer of technology systems. IS&S continues to understand the value of the CMMI-DEV model and requires its development suppliers to leverage the CMMI-DEV model to benchmark and continuously improve their processes. GM suppliers conduct regular appraisals and share their appraisal results and improvement plans with GM. GM also partners with its suppliers during its CMMI-ACQ appraisals. This practice helps to ensure that suppliers understand GM acquisition processes and reveals opportunities to improve GM and supplier interaction.

One of the fundamental principles implemented by GM’s new sourcing model is that suppliers truly collaborate with each other and with GM. A set of suppliers is targeted for each functional or business area within GM. The suppliers then work to understand the business environment and bring business and technological innovation to GM. When projects are identified, GM partners with integration suppliers to develop the requirements, design, and target architecture. The final design, construction, and deployment are delivered by development suppliers on a firm fixed-price basis. These processes are standardized globally and are a key aspect of GM’s implementation of the CMMI-ACQ. Development suppliers are compensated only for functionality delivered to the business. They are not compensated on a time and materials or cost-plus basis. This approach to compensation ensures that development suppliers understand the business problem, properly identify project risks, and work jointly with IS&S to ensure that business value is delivered to GM customers.

A second fundamental principle implemented by GM is that IS&S does not mandate how suppliers develop systems. GM recognizes that its IT suppliers are software development organizations that have mature processes for developing systems. GM and its suppliers agree on the deliverables for each project, and the suppliers are allowed to determine and use the appropriate development methodology.

GM has developed global standard processes based on CMMI-ACQ that describe the overall delivery processes and the processes executed internally by GM. These processes specify the activities and deliverables required at each phase of the project. They are supported by contracts that define the touch points and deliverables. The contracts also specify that suppliers have to develop their own processes which enable quick responses to new development requests and effective and efficient system delivery. Utilizing these global processes, both GM and supplier teams spend less time working on sales activities and proposals, and devote more time to innovation and development of new solutions to move the business.

Reducing the costs of these activities, as well as simplifying the IT landscape, allows greater investment in new and innovative technologies. This development work is more effective because of improvements in requirements. By jointly collaborating on and defining technology standards, GM is also able to leverage the innovation of its top suppliers without sacrificing the ownership and direction of its technical environment. The new GM-Supplier business model, CMMI-ACQ processes, and continuous improvement have allowed GM IS&S to deliver more capabilities to its business customers while lowering its costs to one of the lowest per vehicle in the automotive industry.

The entire GM organization is focused on building great cars and trucks, developing the next generation of fuel-efficient drivetrains, and ensuring that GM continues to excel in vehicle styling and quality. IS&S has realized significant benefits from using CMMI-ACQ such that GM’s IT is well positioned to fully support and mobilize these corporate goals.

General Motors Corp. (NYSE: GM) is a large automotive vehicle manufacturer and focuses on building great cars and trucks for the global market. The corporation is headquartered in the United States; however, GM operates as a truly global company and has a network of design, manufacturing, service, and marketing facilities supported by about two hundred sixty-six thousand employees located around the globe.

In 2007, GM sold 9.3 million units globally. GM has a sophisticated branding strategy that consists of global brands such as Cadillac, Chevrolet, and Saab; and regional brands including Buick, GMC, GM Daewoo, Holden, Opel, Pontiac, Saturn, and Vauxhall. GM manufactures vehicles in more than 35 countries using 375 million square feet of manufacturing space. These products are distributed globally and are sold in more than 200 countries through an extensive dealer network. GM also participates in several joint ventures that produce vehicles for local and emerging markets.

The vehicles designed by GM are some of the most sophisticated and complex products in the marketplace. Each vehicle is a custom-configured product that contains approximately five thousand unique parts and assemblies. The manufacturing process requires a complex supply chain that obtains materials from more than 3,200 sources globally. These materials are delivered every day to GM manufacturing facilities “just-in-time” for production.

GM is also a leader in the automotive telematics industry. GM’s OnStar division provides real-time communication with vehicles to provide safety, security, and information services to vehicle owners and passengers. OnStar services include crash notification, medical emergency support, stolen-vehicle recovery assistance, vehicle maintenance monitoring, concierge services, and turn-by-turn navigation services.

Considering the breadth of its enterprise, the complexity of its products, and the volume of its business, GM is one of the most complex organizations in the world. The management team and employee base within GM are focused on building great cars and trucks and on bringing innovative vehicle products and services to the global market. The IS&S organization is focused on enabling this innovation, reducing technology complexity, and ensuring that GM’s IT systems are secure and can rapidly respond to new market directions.

GM Information Systems & Services (IS&S) provides IT products and services to the GM business globally. The continuing objective of IS&S is to provide world-class IT that propels GM to global leadership in transportation products and related services. IS&S is led by Group Vice President and CIO Ralph Szygenda, who is also a member of GM’s most senior management committee, the GM Automotive Strategy Board. Mr. Szygenda has led the IS&S organization through several transformations as it has evolved to support and foster innovation within GM.

Historically, GM has been an early adopter and pioneer in IT. This distinction was often necessitated by the complexity and scale of the GM operations. However, before 1984 there was no central IT organization within GM, and the regional structures sourced the majority of IT products and services. Only a few core systems were used globally.

In 1984, GM entered its first generation of IT sourcing by purchasing a global IT services company that was a leader in large-scale IT systems. GM utilized this firm as the sole supplier of IT services to the enterprise. Supplier personnel interacted directly with the GM business and were tasked with building a common global infrastructure, simplifying diverse systems, and providing common service globally. Within GM, this is referred to as the first-generation sourcing model (see Figure 7.2). It provided GM with the benefit of a single IT provider to optimize infrastructure and operations.

In the mid-1990s, GM senior management realized that IT was a strategic part of business operations and that IT strategy and accountability must be internal to the organization and must not reside with a supplier. With this insight, GM designed and entered its second-generation sourcing model in 1996. This model included creating IS&S and recruiting GM’s first global CIO. The global CIO developed the mission for IS&S and built the IS&S organization to drive the strategy and deliver innovation to the organization. This creation of IS&S and partnership with multiple suppliers is known as the second-generation sourcing model. In this model, the IS&S department became the primary interface to the business, understood the business strategy, and selected the systems and technology. IS&S then selected IT partners to develop, implement, and operate the business information systems.

The key benefit of the second-generation model was that GM developed internal IT capabilities. As an internal organization, IS&S was able to develop strategies and standards that drove the strategic interests of GM. In this model, GM also began to manage key technical development and support teams to obtain business and systems knowledge that had migrated to the supplier base. With this knowledge, IS&S was able to engage alternative suppliers for IT projects and sustain its activities. The new supplier base helped to drive new innovation with GM but introduced the complexity of GM having to manage a significant number of suppliers. It often required IS&S personnel to oversee integration activities, perform low-level problem solving, and resolve supplier-to-supplier technical and communication issues. During this time, GM also began to adopt CMMI-DEV as a model of best practices to standardize processes globally.

By 2003, IS&S had developed sufficient business and system knowledge to begin to structure GM’s third-generation IT sourcing model. The primary goals of the new model were to drive standardization, simplification, and collaboration throughout GM’s global IT structure. The third-generation model completed the transition of IS&S from a regionally aligned structure to a global structure.

When developing the third-generation model, GM leadership analyzed the benefits and realizations of the first- and second-generation sourcing models. They also analyzed the results that GM obtained from a multiyear initiative using CMMI-DEV to drive improvement and standardization across IS&S. With this data, GM approached the SEI for guidance and best practices for sourcing or acquisition organizations. After further review, the two organizations concluded that CMMI-DEV is an excellent model for organizations that develop systems but does not provide the right guidance for organizations that source or acquire systems. This interaction started what was eventually to become CMMI-ACQ, a new CMMI model focused on the capabilities of the acquirer. The analysis, along with the joint work on CMMI-ACQ with suppliers and other high-performing acquisition organizations, helped GM to establish some guiding principles for structuring the third-generation sourcing model. These principles include the following.

• GM IS&S will maintain the relationship with the business, understand the business strategy and process, and be accountable for delivering the solution to the business.

• With knowledge of the business strategy, GM IS&S will determine the business process impact, develop system requirements, and define the technical architecture for all systems.

• GM will standardize on a set of suppliers to provide system development and sustain activities aligned with GM business processes (e.g., manufacturing, supply chain, marketing, OnStar, and engineering).

• Suppliers are expected to bring business process domain expertise and technological innovation.

• Suppliers are expected to understand the GM environment, collaborate, and resolve integration issues without GM involvement.

• The pricing of all projects will be firm fixed price and payment will be based on tangible business deliverables.

In addition to the guiding principles for supplier sourcing, GM understood that it must align its internal IS&S organization to the global lines of business within GM. Prior to this adjustment, the IT strategy was driven by regional needs and each region was responsible for developing and managing global solutions. Regional business leaders would engage the regional IS&S units to help them with IT needs. GM realized that this model made it difficult to drive simplification because of the different priorities and business cycles of the regions. IS&S leaders now understood that simplification and standardization could be achieved only if the strategy was aligned with line-of-business goals, global solutions were developed to satisfy the strategy, and regional deployments of solutions were coordinated with regional business cycles.

To support the objectives of simplification and standardization, the IS&S organizational structure was aligned into three global virtual “factories” (see Figure 7.3). The System Delivery Factory (SDF) consists of line-of-business or business process area organizations and is responsible for development, enhancement, deployment, and standardization of all systems globally. The Services Factory (SF) has global responsibility for all operations, infrastructure, network, and IT security for GM. Supporting both of these is the Business Management Factory (BMF). The BMF organization provides essential services such as central contracting support, compliance, finance management, and business strategy development to the other factories. The leadership, strategy, and management of each factory are provided by GM executives. Each virtual factory also partners with a supplier to provide integration, project support, quality, and coordination services.

In addition to the three factories, IS&S leadership also includes regional CIO organizations. The CIO organizations align with the region-based GM business organizations in North America, Latin America-Africa-Middle East, Asia Pacific, and Europe. They ensure that the needs of the regional business units are understood and that IT strategies and plans align with regional business objectives.

To ensure that IS&S is always aligned to actual business activities, Process Information Officers (PIOs) are a critical part of the leadership matrix and report directly to the global CIO. The PIO organizations are aligned with the GM business process functions and have global responsibility for the IT needs and strategy for the business process. There are separate PIO organizations for each of the following business process areas: Product Development, Manufacturing and Quality, Purchasing and Supply Chain, Sales-Service and Marketing, Business Services, and OnStar. Each PIO aligns with a senior business process officer and coordinates the IT strategy for the global process area. PIO organizations are the focal point for aligning with the business and driving innovation for the GM business areas. Each PIO organization contains a delivery center, which participates in SDF, and these PIO delivery centers are responsible for the delivery of all projects to the business.

The IS&S structure of PIO, CIO, and factory organizations provides GM with many benefits. For instance, this structure provides clear lines of governance for global IS&S and within each factory. In addition, the factories clearly identify responsibilities and interface touch points through established standardized processes within themselves and among each other, and the interfactory processes streamline the effort to move among factories, yet also provide natural quality and coordination checks for projects and operations. Also, the PIO and CIO organizations bring line-of-business and regional business process alignment to all initiatives; this representation ensures coordination of global strategies with regional priorities and time frames. And finally, governance and technology issues are resolved swiftly via weekly global meetings of the senior IS&S executives and corresponding meetings of the executives within each factory.

This case study is focused on the work within the SDF of IS&S, which is responsible for delivering new capabilities to the GM business. The SDF delivers new capabilities to the business by partnering with the business, developing strategies, identifying and specifying projects, and then sourcing the development and deployment with fixed-price projects from suppliers. To accomplish these goals, the SDF has created standard organizational, governance, and project-execution processes that align with CMMI-ACQ.

The organizational structure of the SDF consists of the PIO organizations and a Chief Systems & Technology Office (CS&TO) organization (see Figure 7.4). The PIO organizations align with business areas to understand their needs, deliver systems, and help drive innovation within the business. CS&TO coordinates across PIO areas to drive IT strategy, standardization, and innovation across the enterprise through collaboration across the PIO areas and the business units.

The PIO organizations have the responsibility of partnering with the business to drive innovation and efficiency. They do this by developing new systems, enhancing existing systems, and streamlining the IT landscape for their respective business units. To accomplish these objectives, each PIO organizes resources by the following critical functions: Strategy, Architecture, Delivery Center, and Sustain. The Strategy function works with the line-of-business and leading technology partners to develop IT strategies and plans that align with business goals. The Architecture function develops the overriding systems architecture for the line of business, develops high-level architectures for projects, and collaborates with CS&TO to develop the enterprise architecture for the entire GM enterprise. The Delivery Center function is responsible for the delivery of all projects. This includes project management, business modeling, requirements development, quality assurance, deployment, and Project Management Organization (PMO) support. The Sustain function provides minor enhancements to systems once they are in production.

The CS&TO organization is led by the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) for GM and has three primary functions relevant to the CMMI-ACQ model: Process and Program Management, Systems Engineering, and Emerging Technologies. The Process and Program Management function collaborates with the PIO organizations for development and improvement of all processes, tools, and support systems for the delivery center. The Systems Engineering function collaborates with PIO areas to develop the enterprise architecture, maintain and improve technology standards, and identify cross-PIO technology synergies. The Emerging Technologies laboratory serves as a focal point for innovation and new technology across IS&S. Each of these functional areas within CS&TO has an executive steering council that includes members from the PIO organizations. This ensures that process and technology standards always align with the needs of the organizations that deliver systems to the business.

The primary purposes of governance in the SDF are to provide clear process and technology standards, continually improve standardized work within the delivery centers, and gain operational efficiency by identifying synergies with the factory. In addition to these goals, the governance must be nimble, quickly respond to issues, and capitalize on opportunities. GM realized that proper governance must provide the proper balance of strategic and operational objectives and ensure that governance is developed and agreed to by practitioners across the factory. To accomplish this, GM developed a structure that is led by the CS&TO organization and has executive representation from each of the PIO areas. Governance meetings are held every week, and all meetings use appropriate technology to ensure global involvement.

The primary governance structure consists of two executive councils: the System Factory Management Council (SFMC) and the Joint Architecture Management Council (JAMC). The SFMC is responsible for developing the strategy for IS&S delivery processes, institutionalizing program management, and improving the operations of the factory. The JAMC is responsible for approving IT standard components and setting technical direction for IT solutions at GM. Each council meets on a weekly basis so that process and technical issues can be addressed and communicated in a timely manner.

The members of the councils consist of executives from each of the PIO areas and CS&TO. Members of the CIO teams often attend to ensure that regional viewpoints are represented. Although the JAMC and SFMC are separate councils to address process and technology, there is partial overlap of staff members between the two councils to ensure continuity and alignment. The two council meetings are held back to back, and joint meetings are often held to address topics that involve both process and technology.

Operationally, the SFMC and JAMC strive to keep the pace of the meetings brisk and focused to make efficient use of the council’s time. When initiatives require extensive research or process, the council members form small work teams to develop solutions and recommendations. These work teams are usually led by one of the council members, and the PIO organizations provide staff members to participate. Typical topics addressed by work teams include process improvement issues, new-technology evaluations, and improvement of interfaces with other factory processes. The teams are given a high-level objective as well as the freedom to find the right solution for GM. This approach ensures that all areas can participate in initiatives and provides the IS&S staff with the opportunity to work on cross-functional teams and gain exposure to other executives.

Each factory in IS&S benefits from the adoption of CMMI-ACQ, but the SDF is the main engine that drives new capability to the business. By aligning the people and processes to the model, the SDF has become a more mature acquisition organization. The next section describes how GM has built the right capabilities internally to deliver systems to the business through partnering with world-class IT suppliers.

GM realized that proper implementation of CMMI-ACQ meant internalizing the model, developing a deep understanding of the authors’ intent when they wrote the practices, and designing an implementation that aligns with the culture of GM. When developing the process, the SDF had to ensure that the practices were translated into work steps that could be followed by GM personnel globally. Due to the complexity of the organization, significant thought was given to how the implementation of these practices impacted organizational processes, related structures, and contracts. Aligning these structural elements was a significant organizational and process design challenge. One of the first steps in addressing this challenge was to clearly identify which parts of the delivery process were the responsibility of GM and which parts would be the responsibility of the supplier. Figure 7.5 shows the conceptual architecture of the high-level process. Following this process, consistent with the guiding principles, GM remains accountable to the business, develops the requirements, and retains project management responsibilities. The supplier develops the solution using its own methodology and delivers well-defined deliverables, metrics, and status to GM through standardized interfaces.

Based on this process vision, GM’s process development team designed a process architecture that had at its foundation a series of “rules” known as standardized work. These standardized work rules were approved by the highest levels of IT management at the company. Global training sessions were provided to all IS&S employees and suppliers to ensure a consistent understanding and interpretation of these work rules. The standardized work rules provided boundaries and constraints that cross-functional teams used to develop processes for project teams to execute. The resultant processes were part of GM’s IT delivery framework called the System Delivery Process (SDP).

The SDP supports different project types through appropriate levels of process and oversight based on the size, complexity, and criticality of the project. The project teams select the project type using predefined criteria published in the SDP with assistance from the project management office and lead architect. The project type selected by most significant GM projects is the Standard type. Standard projects start with the full framework and tailor that framework to define the project’s unique process. Each phase of the SDP framework has activities, templates, and examples to help with project execution. The other project types include Express and Express-Lite. Express projects start with a smaller set of processes and are tailored accordingly to meet their project needs. Express-Lite projects are used primarily for maintenance and have appropriate processes defined. The different project types, along with the tailoring process, ensure that project teams are not burdened with unnecessary overhead and that management has oversight and insight into project activities.

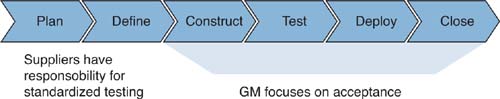

The Standard project type consists of six phases: Plan, Define, Construct, Test, Deploy, and Close. Depending on the complexity of the project, Standard projects are often planned and executed using two “super” phases: Plan/Define and Construct to Close (see Figure 7.6). During Plan/Define, GM establishes a priority for the project, assigns GM resources, and understands the business needs and impacts. Then GM develops the requirements and technical strategy for the project before approaching a supplier. GM may utilize suppliers to provide specific expertise and additional bandwidth during the Plan/Define phase. In these instances, GM remains accountable for the deliverables, and supplier personnel are managed by the GM project manager. In this instance, suppliers can be engaged on a time and materials basis because they are under direct supervision of a GM project manager. Before completion of the Define phase, the suppliers capable of delivering the systems are engaged to submit a fixed-price proposal based on a standard bid request process. The scope proposal includes all development, deployment, and transition work necessary to bring the system into the GM environment.

The Construct to Close phases (i.e., Construct, Test, Deploy, and Close) are much different from the Plan/Define phase. During these phases the GM activities focus on supplier management and oversight, as well as business relationship management. GM does not prescribe the supplier development methodology. GM engages only high-maturity development organizations and wants to ensure that these organizations fully leverage their development capabilities. Based on this philosophy, GM monitors progress and quality, but does not manage the tasks, resources, or environments used for development.

During the Construct phase, GM sets expectations for the supplier and requires the supplier to obtain the necessary environments and to design and develop the system. GM accepts the detailed system designs and test plans developed by the supplier. The supplier then constructs the system and demonstrates complete functionality to GM before leaving the Construct phase.

In the Test phase, the system is moved to the targeted hosting center and is placed into a pre-production environment. In this environment, tests are performed to verify the functionality, performance, scalability, and security of the system. The supplier is responsible for performing these tests and providing GM with the results. After these tests are accepted, the GM project manager will engage the business user for a User Acceptance Test. Once the business customer accepts the system, the supplier deploys the system in coordination with the business-driven training and process rollout.

GM expects suppliers to deliver high-quality systems into production. In accordance with this, suppliers provide GM with rolling 90-day warranties for all systems. The warranty begins when the systems are first deployed into production. During the warranty period, the supplier is responsible for addressing all high-severity defects encountered in the production environment, and the warranty period for the system is reset for an additional 90 days upon remediation of the defect.

In addition to the activities in each phase, recurring activities are defined in the SDP that describe how the project team periodically ensures that the project is executing according to plan (from both a GM and a supplier perspective) and that management is provided with appropriate updates. Standard metrics are collected and reported. Work products are baselined, changes are evaluated and decided upon, and auditors independent of the projects conduct process reviews to ensure that processes are being followed.

Figure 7.7 shows more details regarding the activities conducted in the execution of a GM Standard project.

The SDP was purposely developed to align with CMMI-ACQ. GM had to internalize the model and translate its intent into meaningful processes to ensure that the users of the SDP could relate to the terms in the way they have to execute. Before SDP could be deployed, it was reviewed by representatives from each business unit and geography described in the IS&S organizational structure earlier. The next section describes some of the CMMI-ACQ process areas and how GM implemented them at IS&S.

GM IS&S recognizes the importance of each component of the CMMI-ACQ model. Certain process areas, however, are critical to the success of IT acquisition for GM. The sections that follow discuss these areas, the value they contribute to GM, and GM’s implementation of their practices.

As GM aligned its processes with the CMMI-ACQ model and the new IT sourcing model, IS&S leadership recognized the criticality of developing effective requirements in collaboration with their GM business customers. Unclear or incorrect business and system requirements can compromise functionality and the business objective. Analysis of project history demonstrated that improper requirements definition and management were the major causes of project delays and cost overruns. With this understanding, it became a priority to define a robust requirements development process that aligns to the CMMI-ACQ model specific goal 1, “Develop Customer Requirements.”

The process development team began by identifying the essential stakeholders and participants in requirements development. Roles were defined for a requirements lead, an organizational role responsible for requirements ownership throughout the project and oversight of requirements across multiple projects, and for a requirements analyst whose primary responsibility is requirements elicitation and documentation. Processes describing how these roles interact, and the deliverables they produce, were defined.

An essential objective of the requirements development process is to accurately capture the knowledge of GM business representatives. History has proven that the best technology in the world cannot compensate for a lack of understanding of business needs. IS&S requirements analysts have effectively utilized business process analysis, early in the process, to understand the business situation and analyze the impacts that process and technology changes may have on it (see Figure 7.8).

Use cases are also developed to model system behavior under various business conditions. Each use case consists of a set of possible sequences of interactions among systems and users in a particular environment and related to a particular goal. The use cases must contain all system activities that have significance to the users. In business situations where requirements need even further clarification or are of particular significance to the users, visualization techniques are implemented.

Visualization is the process of presenting a prototype in a form that facilitates an understanding of data and system concepts that are not readily evident in typical textual descriptions. Visualization techniques have proven useful in establishing operational concepts and in validating requirements throughout the requirements lifecycle. A standard visualization tool set is utilized by requirements analysts to develop functional prototypes early in the project. These prototypes mimic the functionality of the proposed systems and are used to collaborate with the business customers, reach alignment, understand new business processes, and innovate on new concepts. The visualizations are also used with the business to clarify and validate requirements, elicit new requirements, and provide a working model of the key functionality of the system. The prototypes are further leveraged with GM development suppliers to ensure that they fully understand the requirements and functionality of the desired solution. Additionally, GM has found that visualizations provide a jump-start in the development of system training materials.

To further improve the efficiency of the requirements process, GM developed the concept of enterprise standard requirements. The genesis for standard requirements is the concept that many requirements are repeated by numerous projects throughout an organization. Within GM, standard requirements cover topics including security, privacy, globalization, regulatory compliance, and disaster recovery. The standard system requirement specification (SRS) was enhanced to include a section that identifies the standard requirements applicable to the project. The process team developed a questionnaire-based tool that guides the requirements team to determine which standard requirements apply to their project. A formal deviation process also was defined for projects to use when they identify that a standard requirement does not apply to a particular project.

Requirements are moved forward as an input to the contracting process once the project team and the business customer are confident that the requirements are accurate, complete, and prioritized. In the contracting process, requirements are allocated to one or more suppliers to achieve effective delivery and integration. Contracts with suppliers define not only their specific deliverables but also their integration activities with other suppliers. Linking the requirements development process directly to the contracting process helps GM align day-to-day work to specific goal 2 of Acquisition Requirements Development process area, “Develop Contractual Requirements.”

GM’s commitment to developing requirements capabilities is reinforced by a central Requirements team within CS&TO. A dedicated team with a full-time program manager oversees several initiatives annually to continuously improve the quality of requirements that GM elicits from its business customers and provides to its suppliers. The team also includes members, on a part-time basis, from each PIO organization and all key suppliers. Like other teams in GM, some team members are located in the United States and some are located in other regions. The team also has suppliers involved so that they can provide input to the processes; that is, training and other assets the team creates and makes available to the enterprise via the corporate intranet (see Figure 7.9).

The suppliers to GM can be thought of as the “customers” of requirements that GM produces. GM works with the suppliers to understand the information required to accurately price and respond to GM’s project requests. Through collaborative efforts across organizational boundaries, the center of excellence team drives improved project performance by ensuring that the requirements at their foundation are effective for system delivery. Suppliers are provided input to the standard requirements, which are provided with each system requirements specification. They also participate in forums to discuss best practices in requirements, including use case development, visualization, and elicitation techniques. Through this ongoing dialog with suppliers, GM ensures that high-quality resources are provided when GM supplements its staff. This dialog also moves both sides forward toward a common understanding of effective requirements. This helps suppliers bid accurately on projects and deliver solutions that delight GM business customers.

The emphasis GM has placed on the importance of requirements has been well received by both internal resources and suppliers. Understanding the business situation helps project teams deliver appropriate technology to meet business needs, and visualization has brought that understanding to new levels of clarity for both the customer and the provider. Since project teams cross organizational boundaries, it is absolutely critical that projects develop accurate requirements. If requirements are ambiguous, changes to these requirements are very expensive since they may require contract changes. Identifying standard requirements has institutionalized consistency in critical areas and helped the project teams operate more efficiently. In the long run, GM’s investment in the center of excellence and other requirements initiatives will continue to generate high returns through successful projects for GM.

Project management for an acquisition organization is as important, if not more important, than project management in an organization where systems are developed internally. Project managers have to actively manage the commitments and tasks of the acquisition team in addition to understanding the true status of the supplier commitments. In organizations that acquire technology products and services, acquisition project managers must ensure that they actively manage the project and that they do not delegate management responsibilities to suppliers. It is only through active management that the acquisition project manager will identify project issues and be prepared to proactively take corrective action.

GM realizes that successful projects require a strong GM project manager who is accountable to the business customer and who will actively manage suppliers. GM project managers are trained on SDP and are careful that they manage suppliers to ensure that commitments and deliverables are fulfilled. They are equally careful that they do not manage the staff or tasks of the supplier.

Effective and efficient project management is critical to successful acquisition of technology. For GM projects to be successful, they must meet the goals of Project Planning and Project Monitoring and Control. To this end, the SDP clearly defines the GM IS&S project manager role, and the processes for developing a comprehensive, integrated project plan, with regular touch points for monitoring and controlling both GM and supplier activities. This GM IS&S project manager is accountable for delivery to the business customer and has to balance the amount of effort spent managing to achieve the appropriate amount of supplier oversight without performing the role for which the supplier is paid by GM.

During project planning, the project teams build a plan to realize the vision established during project funding. Initial planning steps ensure that the right resources, including systems engineers, requirements analysts, the PMO, and the business customer, are engaged to start the project. These steps include development of requirements, as described earlier, development of the acquisition strategy, and project estimation. The team also considers how the solution will be deployed and where it will be hosted.

GM’s project managers and estimation experts use a standard estimation process to develop the project estimate (see Figure 7.10). The estimation process is used to estimate both GM and supplier activities. The standard process also provides a structured approach to estimating based on historical data, and four additional estimation techniques (function-point-based and use-case-based) can be added via tailoring to enhance the accuracy of the estimate. The foundation for, and critical input to, the estimate are the combination of business and system requirements along with the acquisition strategy, any of which can drive overall cost and effort and must be clear in order to engage suppliers.

Following GM’s estimation, suppliers are engaged to propose solutions to meet their allocated requirements within the context of the project activities and deliverables. Multiple suppliers may be involved in the proposal process. For example, one supplier may perform software development while another assumes responsibility for sustaining the solution. GM ensures that a primary supplier is identified, and all of the parties must come to a consensus on the project parameters. When this is accomplished and the proposal is accepted, the GM project manager integrates the plans into one overall plan for project delivery. Then the project manager aligns the supplier project team with the project expectations.

The first step in bringing on board the supplier project team, which may or may not have been involved with the proposal process, is a meeting between the GM team and the supplier team. The overall plan is reviewed, and suppliers describe their tailored processes for the specific project. The team sets expectations for delivery and acceptance of work products and deliverables. The team also confirms expectations for metrics to be reported and periodic touch points.

As defined in the standard contracts, supplier project managers must meet with the GM IS&S project manager on a regular basis so that IS&S does not lose visibility and can help remove roadblocks. During project progress reviews, the team reviews the integrated plan and schedule, and issues may be escalated for GM resolution. If issues are raised, GM and the supplier determine the appropriate corrective action and manage it to closure. Risks are regularly reviewed and mitigated to maintain high, on-time delivery standards. GM project managers focus on actively managing the outcomes and deliverables of the suppliers, rather than monitoring and controlling the tasks themselves (see Figure 7.10).

With a wide variety of stakeholders to satisfy, from the business customer to other IS&S groups to suppliers, GM project managers must establish and maintain plans that communicate direction and provide a mechanism for tracking. The monitoring and control activity includes not only ensuring supplier oversight but also ensuring that GM resources are engaged and are meeting their commitments. Developing and executing processes that enable these activities across GM align IS&S to the Project Planning and Project Monitoring and Control process areas in CMMI-ACQ.

When the GM team and the supplier team collaborate as described in the preceding section, the opportunity to deliver value to the business increases significantly. Additional benefits are achieved by incorporating practices from the CMMI-ACQ Integrated Project Management practice. Accordingly, GM has invested in processes and tools that drive integration and synergy. The processes enable projects to tailor the SDP to meet project-specific requirements, manage the project using an overall integrated plan, and ensure that relevant stakeholders are involved.

Project tailoring of the SDP is executed using a standard tailoring matrix. The matrix shows the standard processes that projects are expected to follow, as well as decisions the projects make to “tailor in” additional processes to ensure quality delivery or to “tailor out” processes that are not applicable to the unique aspects of the project. The PMO reviews the project tailoring to determine additional opportunities to deliver more efficiently or effectively based on the performance of other projects. The executive in charge of the delivery center then approves the tailoring.

Once tailoring is complete, the team develops the Integrated Project Plan (IPP), which integrates all of the other plans for the project. The IPP allows any stakeholder to quickly understand the project scope, resources, and timing. To ensure that this plan is developed consistently across all IS&S projects, a template is included in the SDP. The plan covers acquisition strategy, milestones, deliverables, quality assurance, configuration management, and many other critical areas. The IPP is developed in two phases: The first phase occurs before planning and requirements and the second phase occurs afterward. The IPP is then maintained throughout the life of the project.

GM provides a number of tools to project managers to assist in coordination of and collaboration with many stakeholders, and to provide consistency across projects. The GM SDP RASIC is one of these tools. The RASIC chart describes the roles of team members who are Responsible for executing and Approving the process. The chart also describes Support roles, and roles that should be Informed of status and completion and Consulted along the way. . The RASIC chart is a global standard for GM, and each project has individuals assuming these roles (see Figure 7.11 for an excerpt).

Project teams within GM are encouraged to reuse process assets when feasible, and to contribute to continuous improvement of common assets. Business units submit examples of best practices to the Integrator Project Management Office (IPMO). The IPMO coaches projects on best practices, and works with the corporate process team to incorporate these best practices into the SDP. Project team members may also provide process improvement ideas electronically, at any time, directly to the SDP continuous improvement team, which logs and tracks each proposal until it is implemented or declined.

Integrating all project plans into the IPP and establishing a standard RASIC chart positions GM project managers to successfully deliver projects. The project teams feed improvements back into the organizational process assets based on their experience using them. Together, these activities help GM to align its work to the goals of Integrated Project Management and to ensure that integrated GM and supplier teams continue to deliver successful projects with the available budget and time as specified in the supplier agreements.

Relationships between acquirers and suppliers are complex, and the agreements between them, which can vary from company to company and region to region, add to the complexity. GM IS&S leveraged lessons learned by the GM business, and took significant steps to ensure that the supplier agreements would support the new IT sourcing model by enabling a cohesive working environment between the supplier and GM, and among suppliers.

IS&S analyzed the different types of sourcing arrangements that were in place and decided to capitalize on best practices from GM’s supply chain organization. IS&S negotiated general service contracts (GSCs) with a select group of large, global IT companies capable of supporting the GM business. Each supplier is aligned to one or more of the major business processes supported by the IS&S PIO leaders. In exchange for a long-term contract with GM that allowed the suppliers to plan, learn, and staff accordingly, the suppliers are expected to provide business domain knowledge to the business unit they support. Identifying target suppliers and negotiating long-term GSCs provides significant efficiencies for GM and the supplier. It allows project request and response activities to focus on project deliverables and avoids project teams having to negotiate terms and conditions for each project.

The GM project team packages its requirements in an Information Technology Service Request (ITSR) for the supplier, which is very similar to a Request for Proposal (RFP), and the supplier team provides a response. The two teams then negotiate scope, effort, and timing, but do not have to negotiate rates or legal terms and conditions, which are already defined in the GSC. If the project has unique needs that the main supplier cannot meet, the project team may pursue new suppliers using a rigorous solicitation process.

Key to the sourcing model, the supplier agreements also define how suppliers must interact with other suppliers. For example, if one supplier develops a solution and another supplier has to support it, both suppliers must agree that the solution is ready for transition.

Clear, robust agreements between GM and its suppliers enable this complex internal and external resourced organization to deliver and support capabilities for the GM business. The contracts have been structured in a way that minimizes negotiations and allows teams to spend more time on solutions. These agreements not only set expectations about how suppliers will support GM, but also specify how suppliers interact with other suppliers. They also reference GM standards that suppliers will have to meet in order to deploy their solution in the GM environment.

GM has partnered with technical resources from IT suppliers for many years. Throughout this time frame, GM has observed that there is often inconsistency regarding technical recommendations among suppliers, and often from within the same suppliers. Supplier architects may advocate particular vendors, product lines, or technologies that they are familiar with, rather than what is in the best interest of the customer. GM realized that in order to drive standardization and simplification, IS&S must drive the overall architecture of systems, and institute a strong governance process to determine which technology can be used in GM systems.

For GM to maintain control over the IS&S technical landscape, a corporate process was established to submit, review, and approve technology components. Once approved, the components become a part of GM IT Standards and are then eligible for inclusion in new solutions. The Standards group approves standard infrastructure (e.g., hardware, network, and supporting software), commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) business applications, and technology platforms. Suppliers submit a Bill-of-IT, a list of the technology components to be used, that conforms to the established IT standards. The GM architect for the project (identified in the RASIC), with support from the Joint Architecture Management Council (JAMC) mentioned previously, ensures that the solution makes sense for the GM environment (see Figure 7.12). Solutions not conforming to the standards must be validated and approved by a global, cross-functional committee. Technical reviews are conducted throughout the life of the project to ensure that solution designs are aligned with both functional and technical requirements.

In addition to project-level technical management, a corporate-level team of systems engineers looks for opportunities to leverage technologies across projects and business units. This team has successfully consolidated the number of systems GM utilizes globally. Continued success in this area allows the company to continue to reduce GM’s budget for maintenance and operations, and to shift that spending instead to reinvest in delivering new capabilities to the GM business.

To ensure that the solutions developed by the IT suppliers support the GM business as specified, validation steps have been incorporated throughout the project lifecycle (see Figure 7.13). GM validates supplier designs, tests, and deployment results. This validation occurs by accepting these and other supplier deliverables at predefined points in the project.

Each development project has a predefined set of deliverables. In the Construct, Test, and Deploy phases of the SDP, these deliverables are the responsibility of the supplier, and they include detailed solution design (within the constraints of IT standards), testing artifacts (including test plans, test cases, and test results), user acceptance and training, and deployment to one or more GM environments. For each deliverable, a standard set of acceptance criteria is provided to the supplier before work commences. The validation is not complete until each acceptance criterion has been met and confirmed by GM.

Acceptance review dates are scheduled based on supplier commitments to provide project deliverables and are documented in the integrated plan. In an acceptance review, the supplier provides context for the deliverable to the evaluating GM subject matter experts. The acceptance criteria are then used to determine whether the deliverable is ready. If the deliverable is ready, it is accepted and the supplier is approved for payment. If the deliverable is not ready, GM notes the criteria the deliverable failed to meet. The supplier resolves any defects and subsequent reviews occur until the deliverable is acceptable. GM suppliers demonstrate capability by delivering a high percentage of first-time acceptances across multiple projects.

A unique characteristic of user acceptance testing within GM is that both the system and the training materials are accepted. In addition to the system functionality itself, users must have whatever additional information they need to leverage the system prior to the supplier receiving full payment. The GM operations supplier responsible for supporting the new application also participates in the acceptance of user guides and related materials.

GM suppliers operate under fixed-price contracts, and are paid only after validation of their deliverables. Upon acceptance of a deliverable, contract management and finance representatives are notified and the supplier is allowed to invoice. Thus, acquisition validation at GM must be tightly aligned with the development and management of supplier agreements.

Organizations that acquire rather than develop their IT products and services need to manage their agreements once they are established. Suppliers typically will not exceed their commitments, and it is up to the acquirer to ensure that the commitments are met.

At GM, project and contract managers collaborate to ensure that GSC requirements and ITSR requirements are met. Project managers assess and report supplier performance throughout project execution. Contract managers regularly summarize the results of project performance and customer feedback surveys and provide feedback to suppliers through a standard supplier score card. If inadequate performance is detected in either of these channels, a formal corrective action process remedies any issues and facilitates improvements needed to enhance future performance.

To ensure that solutions are sustainable, GM requires a 90-day warranty period for all new applications, commencing on the deployment of the application to its final environment. During this period, the supplier keeps the development team in place to resolve any issues. Warranties are extended for an additional 90 days if issues are discovered during the initial period.

GM manages supplier agreements through multiple channels. The project manager and contract manager both provide suppliers with regular feedback, and the 90-day warranty period is an incentive to ensure that defects are not brought into the GM environment.

GM IS&S realizes that its own commitment to quality drives the eventual success of any project it conducts. GM deliverables must be accurate, and project stakeholders must commit to the deliverables, if the projects that produce them are going to be successful. To ensure this high level of quality and commitment, GM performs verification throughout the lifecycle of each project on the deliverables for which GM is responsible. GM also participates in verification of supplier deliverables when appropriate.

A project selects the deliverables to be verified during the tailoring process. For most deliverables that GM produces, a peer review is conducted with a standard checklist of criteria to ensure that reviewers use every opportunity to identify defects. For deliverables not undergoing a peer review, an inspection and approval process is often used.

The “peer review” process at IS&S is unique in comparison to most industry standards. IS&S uses peer reviews not only to receive feedback from peers in comparable roles, but also to gather feedback from stakeholders affected by the work product. For example, when a project peer reviews an SRS, requirements Subject Matter Experts SMEs are joined by test leads to ensure that the requirements are testable, and by the project architect to ensure that the requirements are clear for the solution architecture. By including these stakeholders earlier in the development lifecycle, GM teams are building commitment and consensus to the project approach. GM truly believes that the costs associated with involving stakeholders early in the process are much lower than the costs incurred when defects are identified later in the project lifecycle, when they are much more expensive to fix.

By definition, acquisition practices cross organizational boundaries as acquirers engage suppliers to develop their systems. Verification practices are critical to the success of the acquirer in engaging a supplier. These practices ensure that the right stakeholders are involved and aligned before the supplier is engaged. Verification also helps to prevent defects from being injected into the lifecycle before expensive processes such as contract changes have to be executed to fix the defects. These processes and others must be measured and analyzed to ensure that they are effective at meeting their objectives.

With an organization as large and complex as GM, there are many opportunities to measure and gather data. When suppliers are engaged, those opportunities increase exponentially as each supplier has metrics that it uses in addition to the metrics inside GM. At GM, measurements that are valuable and sustained over time are focused on measuring performance that will drive management objectives. GM is cautious to collect only those metrics that will be used and can be acted upon. Metric information can become stale as processes change. GM will not burden itself or its suppliers by collecting data that is not actionable.

GM currently gathers data and reports measures that drive the overall objectives of innovation, simplification, and cost reduction. Figure 7.14 highlights some of the unique measurement relationships that GM uses to track progress toward those goals.

IS&S projects at GM gather this data through global standard tools. Derived measures are reported in executive dashboards tailored to each executive’s role. Some dashboards are regionally based (for a CIO in charge of one of GM’s regions) and others are process area based (for a PIO that is in charge of a global process area). Globally derived measures are regularly reported to the Group Vice President in charge of IS&S as well as to staff members for analysis and action.

Several of GM’s business units have been gathering and reporting these measures for many years. They now have sufficient data to quantitatively manage critical processes, not only within GM but also to manage supplier processes. Some pieces of the SDP have been developed in a way that allows for these measures and high-maturity practices to be leveraged by those business units when they are appropriate for the project. GM will continue to evolve these measures and high-maturity practices where they will add the most business value.

The foundation for effective measurement and analysis is clear objectives. GM’s management has been very clear about what it needs from IS&S in terms of innovation, cost reduction, and simplification. IS&S has adopted measures that help the project teams and support organizations focus on delivering on those objectives. Measurement and analysis has been a critical process for IS&S’ success in the acquisition environment, and will continue to be improved over time to adapt to the changing needs of the business.

The CMMI-ACQ model contains many important concepts. GM needed to consider lessons learned from managing IT suppliers, the business environment, and project history to decide where focused efforts were required to achieve the most leverage from the model. GM’s processes align to each process area of the CMMI-ACQ model, but history and vision have driven leadership to focus on the several process areas that were mentioned in the previous paragraphs. Figure 7.15 summarizes these process areas, the unique GM implementation, and the value that these implementations have institutionalized across IS&S.

Realizing the value in the processes was critical to success at GM. Just as critical to success is to deploy those processes globally to the extended IS&S team. Institutionalization around the world is the only way that IS&S will be successful, and the next section describes GM’s approach to this tremendous organizational change.

In an organization as large and complex as GM, making and sustaining significant operational change is very challenging. The new IS&S business model would enable GM to leverage suppliers for innovative solutions that contributed to the GM business, but not unless it was well understood and embraced by the entire organization. To build these acquisition capabilities, GM had to deploy a comprehensive change management strategy, including communications, training, support, and continuous improvement.

The communications strategy involved informing IS&S employees and suppliers of their new roles and responsibilities. Target stakeholders varied from GM employees to GM agents (suppliers in GM roles) to developing suppliers to suppliers of IT system maintenance and support. To reach this wide variety of stakeholders, GM had to use several communication channels.

Town hall-style meetings, conducted live at GM’s North American headquarters and broadcast via Webcast globally, informed GM employees about the new business model and the changes in their roles and responsibilities. These meetings were reinforced with in-person training sessions on standardized work (discussed earlier), which provides boundaries on the processes critical to the success of the new organizational model. GM continues to use town hall meetings to provide strategic information to the GM IS&S community.

Cross-functional teams, composed of GM business and IS&S resources, along with supplier resources, were formed to develop processes at the work instruction level. The results of their work were incorporated into new versions of the SDP and standard RASIC. On return to their respective parts of the extended organization, team participants served as change agents, addressing issues and answering questions regarding the new framework.

Development of the SDP was followed by a global deployment, organizational change, and training program (see Figure 7.16). The new version of SDP that supports CMMI-ACQ was introduced with a set of global “SDP Days.” These were one-day seminars, held globally, that provided a high-level overview of the process and roles of the SDP. This was followed with role-based training courses, delivered in face-to-face environments by trainers with practical experience within and outside the GM environment. Training ranged from executive awareness sessions of a few hours, to multiday training that included individual and team exercises and exams. Training sessions were recorded and made available to new employees and supplier partners.

GM put SDP Coaches in place in each process area and geographic region to continue support of the user community. An SDP Coach serves as the local point of contact for questions regarding the SDP process, and works with project teams to better understand complex topics such as project tailoring and estimating. Coaches also serve as the distribution point for updates to the SDP and are responsible for disseminating changes to their organizations.

Most important to all of these communication vehicles was the ongoing support of the leadership team described in the IS&S overview earlier. The PIOs, CIOs, and other senior executives supported the overall vision. The SFMC and JAMC reinforced communications to project teams and worked together to resolve implementation issues. These IS&S leaders were responsible for the initial push to move the company to its third generation of IT sourcing and are still responsible today for making IS&S a high-performing IT organization.

As one of the largest companies in the world with a global presence, GM has significant experience in making sustainable changes on a large scale. Simply creating processes that align to CMMI-ACQ would not have been enough to institutionalize the vision that IS&S leadership had formed. Training, regular communications, and commitment from executives were necessary to move GM to a more mature “customer” of IT products and services.

GM recognizes that to gain the full benefits of CMMI-ACQ, proper tools must be implemented to facilitate and automate process activities and provide management visibility. Based on its concept of standardized work, GM developed a framework depicting the functionality of tools required for acquisition organizations. This framework, known internally within GM as IT-ERP, reveals that the tools utilized by acquisition organizations can be quite different from those required by development organizations. The tools required in acquisition include requirements definition, architecture management, project management, contract management, and financial controls. The acquisition organization is not concerned with compliers, defect trackers, unit testers, or automated build tools.

GM performed a market analysis and consulted with several major tool vendors regarding their current tool offerings. The results indicated that currently, IT tool sets are targeted toward development organizations and not acquisition organizations. To compensate for this, GM has developed a hybrid approach to tools. It has developed a set of custom-built tools with basic support for support program and application management. It supplements these with requirements visualization, contracting, and architecture tools from various vendors. GM has found that tools from various sources can be difficult to integrate with each other and into an integrated process. The lack of tool integration can cause extra work for project teams and cause delays in properly monitoring and managing project progress and costs. GM is sharing its IT-ERP concept with tool vendors and encouraging them to develop tool sets focused on the acquisition model. GM will continue to monitor the market for integrated acquisition tool sets.

A benefit of using a standard capability maturity model versus a proprietary model is the suite of tools that typically accompany a standard. Such is the case with the CMMI Product Suite. A key component of the SEI’s suite is the Standard CMMI Appraisal Method for Process Improvement (SCAMPI) appraisal method. GM used SCAMPI appraisals to benchmark its business units under the previous CMMI-DEV model, and wanted to continue to use them with CMMI-ACQ to help drive and measure business change.

GM conducted several pilot appraisals following the SCAMPI B and SCAMPI C methods. The appraisals were insightful and drove several improvements to the CMMI-ACQ model based on model change requests from appraisal team members. The appraisals were also valuable as the findings identified improvements for GM’s SDPs, including the example in the next paragraph.

While reviewing Solicitation and Supplier Agreement Development, the appraisal team did not identify anything to prevent GM from meeting its stated CMMI-ACQ goals. However, the team did notice that the contract management and system delivery processes could be better integrated to support project execution. After additional analysis, the process improvement team made improvements to the integration by adding references to contract management information early in the SDP and encouraging project teams to reach out to suppliers earlier so that they would be ready to respond quickly to new ITSRs.

GM is defining its global appraisal strategy as the conclusion on the moratorium for SCAMPI A appraisal approaches. The business value of the appraisals must be weighed against the cost and effort they require, and leveraged accordingly. GM will continue to use appraisals to identify improvements such as the one listed here and drive consistency across the globe.

To drive innovation that addresses business needs, suppliers have to be in lock step with GM so that IS&S can respond when the business requires new capabilities. As such, GM invests heavily in supplier relationships to ensure that GM and key suppliers remain aligned in terms of vision, processes, contracts, and people. Several activities reinforce these relationships.

Annually, GM has a strategic planning session off-site where executives from GM and executives from each supplier establish a common vision of the state of IT, the state of the industry, and where each is moving in the future. The session includes strategic collaboration discussions in which suppliers can describe how they will help GM with business and IT goals, and GM gives direction to suppliers on what they will need to be successful both in the short term and in the long term. The executives collaborate on strategies for key initiatives that will provide opportunities for both the acquirer and the suppliers to be successful.

There are also regular joint forums between acquirers and suppliers at the practitioner level. In addition to the requirements forums discussed earlier, there are project management forums that ensure alignment with GM and supplier project managers. Suppliers regularly participate in process improvement initiatives and sit on the SDP continuous improvement team.

Each key supplier has a GM executive as a mentor. The mentor is involved in a different business unit than the business unit the supplier supports, so the mentor does not have direct influence over contracting decisions. In this situation, mentors can provide candid advice to the supplier about how the supplier can improve performance and success at GM.

Supplier relationships are critical in an acquisition environment. Aligning suppliers with GM and each other is a constant challenge. By investing in forums for executives, project team roles, and process development roles, GM provides a number of opportunities to communicate and align. The relationships that are developed out of these opportunities help drive the combined team toward the overall objective of helping GM design, build, and sell more great cars and trucks.

GM IS&S has realized significant benefits from working with the SEI to develop and apply CMMI-ACQ and plans to continue to work with the SEI on further developments of the CMMI Product Suite. GM will also continue to make improvements to IS&S system delivery processes, ensuring the delivery of high-quality systems to the GM business.

The SDP team within IS&S is constantly monitoring the software engineering community and requesting feedback from its internal organization and supplier base. It uses this feedback to drive future versions of the SDP. At the time this case study was prepared, the SDP team was piloting a version of the SDP that integrated Iterative and Agile development techniques into the acquisition model. After thoroughly analyzing these methodologies and consulting with industry experts, GM has developed an approach that integrates best practices for Agile methodologies and fully aligns with the core principles of the third-generation IT sourcing strategy.

The modifications allow projects to continue to develop robust requirements and visualizations early in the lifecycle. These are used to agree on prioritization with the business and develop a strategy for incremental delivery that aligns with the business goals. With this information, suppliers can develop fixed-price proposals to develop the systems in accordance with the requirements and incremental strategy. At the start of each iteration, business users participate in requirements validation sessions to incorporate their learning from previous iterations. This approach is being piloted by several business units and a strategy for its global deployment is under development.

There are many opportunities to standardize, measure, control, and improve system delivery processes in an environment as complex as that of GM. GM will continue to work with the SEI to identify best practices and next practices that support IS&S in delivering systems to help the business build better cars and trucks. GM will also continue to invest in improvements to its people, processes, and tools to drive innovation.

The CMMI-ACQ model helps GM focus on the capabilities and processes it must excel at in an environment where all IT development and support is sourced. As a capability maturity model, CMMI-ACQ also provides a road map for continuous process improvement. Its design has a broad range of potential applications, as evidenced by its compatibility with the IS&S business model.

After an extensive change management program, IS&S now executes consistent processes, globally, in accordance with its standardized work. Mechanisms are in place to allow the continuous improvement of the SDP, including a governance structure and coaching program. There is a special focus on the areas in which GM must be particularly effective, including requirements development, project management, technical management, and supplier management.

GM has seen significant, beneficial results from the new IS&S business model and the adoption of CMMI-ACQ. The IT cost per vehicle at GM is now among the lowest in the industry. Some of the best IT companies in the world now work together, under the direction of GM, to deliver innovative solutions for the business. Process and technology improvements together have allowed GM IS&S to offer more capability to the business, more efficiently. These improvements have also propelled GM toward world leadership in transportation products and related services.