5.1 This illustration demonstrates how light travels in a straight line.

Chapter 5: Exploring Exposure and Composition

When photographers talk shop, the most common subjects discussed are equipment and exposure settings, such as the f-stop or shutter speed used for a particular shot. Budding photographers especially want to understand the thinking behind their choices. If you want to be a professional photographer, you need to understand the mechanics of exposure. There is no such thing as a perfect exposure. If you correctly exposed every point in your photograph, it would produce a gray sheet of paper. The exposure process is a series of under- and overexposures. It is your job as the photographer, with the help of your camera’s metering system, to find the right combination. Although there are many automatic exposure options, I encourage you to explore and learn more about how exposure works. Don’t settle for what the camera gives you; take charge and create the results you want.

The shallow depth of field in this image was achieved by using a large aperture.

Choosing the Right Exposure

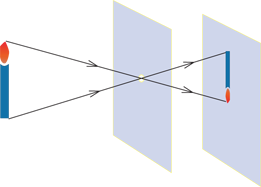

You can turn almost anything into a camera, which is just a lightproof box. Even the room you are in could be a camera if you cover the windows and keep out all of the light. If you place a large white piece of paper on one wall and drill a hole in the other, you see an image of the outside world reflected upside down on the paper. Light travels in a straight line, reflecting from its source. The piece of paper is the light-sensitive material that captures the image. In your camera, the light-sensitive material is electronic, and it is known as a sensor.

5.1 This illustration demonstrates how light travels in a straight line.

The hole in the wall is the aperture that allows light to pass through. If you let the light continuously hit the light-sensitive material, it overexposes the image. You need something—a shutter—to stop the light from traveling into your camera. The intensity of light and the sensitivity of the light-sensitive material (the sensor) also determine how large or small the opening (the aperture) in the wall is, and how long the shutter must remain open.

Fortunately, you don’t have to worry about all of that complicated stuff because your camera has advanced technology that automatically reads the proper exposure. This gives you the flexibility to use the creative zone modes for full or partial control of your camera, or the automatic zone modes for multiple exposure options.

Here are some quick tips to get you started (they are explained in more detail later in this chapter):

▶ Use the Programmed AE mode (![]() ). Consider this P for panic mode. When you are not sure what to do and need to get the shot, let the camera do the thinking.

). Consider this P for panic mode. When you are not sure what to do and need to get the shot, let the camera do the thinking.

▶ Select a high-enough shutter speed. When you hand hold your camera, use 1/60 second or higher to prevent blur. If you want to stop the action, use a shutter speed of more than 1/500 second.

▶ Select the right aperture. The higher the aperture number is, the greater the depth of field.

▶ Select the right ISO setting. The higher the ISO setting is, the less light is needed for an exposure.

▶ Use the Bulb setting (![]() ) for long exposures. This setting holds the shutter open for as long as you press the shutter button. Use a cable release to make this easier and avoid camera shake when pressing the shutter button.

) for long exposures. This setting holds the shutter open for as long as you press the shutter button. Use a cable release to make this easier and avoid camera shake when pressing the shutter button.

▶ Understand the dark side of filters. When you put dark or color filters on your lens, the photograph needs more exposure. This also affects the shutter speed or aperture, depending on what exposure setting you use. The amount of light blocked by the filter is called the filter factor. Knowing how a filter affects your exposure helps you determine what support equipment you might need, such as a tripod.

▶ Know how the shutter speed and aperture work. Increasing the shutter speed by 1 stop cuts the amount of light entering the camera by half; decreasing it by 1 stop doubles the amount of light entering the camera. Opening the aperture by 1 stop doubles the amount of light entering the camera; closing it by 1 stop cuts the amount of light in half.

▶ Meter the exposure. If you photograph a subject at a distance, use a gray card to meter the same lighting conditions to get the best exposure.

A photograph is underexposed when there is not enough light during the exposure process. This makes the photograph look too dark, as shown in Figure 5.2. A photograph that is overexposed has received too much light in the exposure process. This makes the picture look too bright, as shown in Figure 5.3.

5.2 In this underexposed photo, the details are lacking in the shadows. (50mm lens, ISO 100, f/5.0, 1/3000 second)

5.3 In this overexposed image, the details are lacking. (50mm lens, ISO 100, f/1.4, 1/60 second)

The basic zones are automatic; you do not have to make any adjustments when using them. The following is a list of the basic zone modes and when to use them:

▶ Scene Intelligent Auto (![]() ). You can use this all-purpose mode for everyday photography. It analyzes the scene and adjusts the shutter speed, aperture, and focus as needed.

). You can use this all-purpose mode for everyday photography. It analyzes the scene and adjusts the shutter speed, aperture, and focus as needed.

▶ No flash (![]() ). When it is not appropriate or allowed, such as in a museum, this prevents the flash from firing.

). When it is not appropriate or allowed, such as in a museum, this prevents the flash from firing.

▶ Creative Auto (![]() ). Unlike the Scene Intelligent Auto mode (

). Unlike the Scene Intelligent Auto mode (![]() ), in which the camera sets everything for you, Creative Auto mode (

), in which the camera sets everything for you, Creative Auto mode (![]() ) gives you some flexibility to adjust the depth of field, the drive mode, and flash firing. You can also add ambience settings to your photographs.

) gives you some flexibility to adjust the depth of field, the drive mode, and flash firing. You can also add ambience settings to your photographs.

▶ Portrait (![]() ). This mode creates a shallow depth of field, which is helpful for portraits.

). This mode creates a shallow depth of field, which is helpful for portraits.

▶ Landscape (![]() ). This mode creates a large depth of field, which is helpful for panoramic shots.

). This mode creates a large depth of field, which is helpful for panoramic shots.

▶ Close-up (![]() ). Use the macro setting to shoot close-ups or for small-object photography.

). Use the macro setting to shoot close-ups or for small-object photography.

▶ Sports (![]() ). This mode uses a fast shutter speed to stop action. It is commonly used for wildlife, sports, and fast-moving children.

). This mode uses a fast shutter speed to stop action. It is commonly used for wildlife, sports, and fast-moving children.

▶ Night Portrait (![]() ). This slow shutter speed mode helps capture background lights at night. Remember that the flash pops up if the camera detects the need.

). This slow shutter speed mode helps capture background lights at night. Remember that the flash pops up if the camera detects the need.

Setting the shutter speed

Photographs of fast-moving objects frozen in motion, such as a cheetah bounding through the grass toward its prey, are a result of a fast shutter speed. Likewise, a trail of stars advancing across the night sky is the result of a slow shutter speed.

Shutter speed is measured in seconds. Your camera has shutter speed settings that range anywhere from a 30-second exposure to 1/4000 second. In most cases, any speed more than 1/500 second stops action. You start to see more motion blur at 1/30 second or lower; the faster you or your subject is moving, the more blur you see.

When considering shutter speed, ask yourself whether you want to show motion or stop it. If stopping or showing motion is an important element of your photograph, consider using the Shutter-priority AE mode (![]() ). This mode allows you to control the shutter speed, while the camera controls the aperture. Pay attention to the aperture number displayed next to the shutter speed in the viewfinder. If it is blinking, the shutter speed is too high or low for a proper exposure.

). This mode allows you to control the shutter speed, while the camera controls the aperture. Pay attention to the aperture number displayed next to the shutter speed in the viewfinder. If it is blinking, the shutter speed is too high or low for a proper exposure.

TIP The longer the camera lens is, the higher the minimum shutter speed should be to avoid blur from lens movement.

When to use fast shutter speeds

Use a fast shutter speed whenever you want to stop action. When you photograph wildlife, active children, or sports, you generally require faster shutter speeds. This is because the subjects are often moving and motion causes an image to blur at lower shutter speeds. A fast shutter speed is considered over 1/125 second. If you want to stop action with little or no movement, consider 1/500 second. The top shutter speed on your camera is 1/4000 second. You rarely need or reach a shutter speed that fast, unless you are photographing at a high ISO setting in bright sunlight.

Use the Shutter-priority AE mode (![]() ) when photographing sports, wildlife, or any moving subject to help prevent blurring. If you prefer to use the basic zone modes, the Sports mode (

) when photographing sports, wildlife, or any moving subject to help prevent blurring. If you prefer to use the basic zone modes, the Sports mode (![]() ) is a good option because it keeps the shutter at the highest possible setting for every shot. If you are not getting a fast enough shutter speed to achieve the results you want, consider increasing the ISO setting.

) is a good option because it keeps the shutter at the highest possible setting for every shot. If you are not getting a fast enough shutter speed to achieve the results you want, consider increasing the ISO setting.

5.4 When shooting action, such as sports, a high shutter speed freezes the subject. (70-200mm 2.8L lens,130mm, ISO 400, f/4.5, 1/2000 second)

When to use slow shutter speeds

A slow shutter speed is required when you want to show movement. It is also used to show a more ambient background light when using flash. Using motion well in your photos can turn everyday pictures into action-filled images, as shown in Figure 5.5.

If you need a greater depth of field (which is explained later in this chapter), try slowing down the shutter speed until you reach the desired aperture. As the shutter speed decreases, the aperture number needs to increase to keep proper exposure. Landscape and architectural photographers often use very slow shutter speeds, especially in the early morning or late evening, to help keep the aperture numbers high for a greater depth of field. For this type of photography, use a tripod to steady the camera.

Generally, you should use a tripod when the shutter speed is set below 1/60 second. One guideline to remember is if the shutter speed is lower than the focal length of the camera lens, you should use a tripod. This doesn’t always work, however, because there are other factors to consider, such as the movement of your subject. If your subject is still or moving toward you, though, the previous guideline should work. If your subject is moving from side-to-side, a faster shutter speed is usually required.

5.5 This photo shows movement because a slow shutter speed was used. (ISO 200, f/16, at 1/25 second)

Moving water, such as waterfalls or crashing waves, is a great opportunity to influence the outcome of the image with the shutter speed. Use a fast shutter speed, such as 1/500 second, to capture individual water droplets cascading down a falls or to stop the action of breakers crashing onto rocks. Use a slow shutter speed, such as 1/8 second, to bring out the silken flow of the falling water or to create a peaceful seascape. You can use fast and slow shutter speeds to set different visual tones. For example, you can demonstrate speed using the motion blur of a fast-moving train, or convey the power of a hammer hitting a rock by using stop action at the point of impact.

If you need a slower shutter speed, but don’t want to blur your photo, use the Handheld Night Scene mode (![]() ). Canon’s Image Stabilization (IS) lenses are also helpful when lens shake might ruin a good photo opportunity. The stabilization technology cancels out much (if not all) of the blur by adding the equivalent of up to 4 full shutter speed stops.

). Canon’s Image Stabilization (IS) lenses are also helpful when lens shake might ruin a good photo opportunity. The stabilization technology cancels out much (if not all) of the blur by adding the equivalent of up to 4 full shutter speed stops.

CROSS REF For more details about lenses, see Chapter 4.

If you shoot at a slow shutter speed (under 1/60 second), both the background and the subject show motion in the image. How much motion depends on how slow the shutter is, how steady you hold the camera, and the speed and movement of your subject. Try playing with the blur by moving the camera in different directions while you shoot to see what forms and shapes you can create.

5.6 When shooting this image, I quickly turned the camera during the exposure to add movement. (ISO 200, f/16, 1/20 second)

When you use a tripod and set your camera to a slow shutter speed to shoot a moving object, the object shows blur but the background remains in focus. How much blur is created depends on how fast the object is moving and how slow you set the shutter.

5.7 This shot was taken using a tripod while cars sped past at about 40 mph. (ISO 400, f/5.6, 1/6 second)

Panning is a fun technique to use with a slow shutter speed. To do so, track a moving subject with your camera and use a slow shutter speed. This technique delivers an image with the subject in focus against a blurred background, as shown in Figure 5.8.

5.8 Panning creates an image in which the subject is in focus and the background is blurred. (ISO 400, f/18, 1/30 second)

The Bulb setting (![]() ) is commonly used for extra-long exposures to capture streaks of light, as shown in Figure 5.9. Use this setting when you are trying to capture car headlights on the highway, stars moving across the night sky, or the silky movement of water.

) is commonly used for extra-long exposures to capture streaks of light, as shown in Figure 5.9. Use this setting when you are trying to capture car headlights on the highway, stars moving across the night sky, or the silky movement of water.

5.9 I photographed my daughter dancing around in her LED light-covered shoes. You can see the lights, but you can’t see her due to her movement and the slow shutter speed. (ISO 800, f/9.0, 12 seconds, tripod)

Your camera syncs with the flash up to 1/200 second. If you use a faster shutter speed, part of your image will be dark or black because the flash didn’t keep up with the shutter. Fortunately, you can prevent this from happening. Even if you set a higher shutter speed, as soon as you turn on the flash, it reverts to 1/200 second.

Although you can’t set the built-in flash over the 1/200 second sync level, you can slow down the shutter as much as you want. External flashes, such as the Canon Speedlite series, have high-speed sync, which can sync with your top shutter speed of 1/4000 second. When you use a slow shutter speed with flash, you create a ghosting effect. This happens when the flash freezes the subject, but the slow shutter speed causes a blur. If you move the camera in different directions or turn it during the exposure, the result is a motion-filled image.

CROSS REF See Chapter 6 for more details about ghosting.

Night photography and painting with light

Have you ever wanted to create one of those beautiful shots of a skyline at night, or capture a large moon rising over a landscape? Night photography offers many dramatic photographic opportunities—all you need is a little knowledge and the right tools. Two necessary accessories for night photography are a cable release (remote switch) and a tripod. A tripod is necessary to keep the camera steady for long exposures. You can use a cable release to trip the shutter at any shutter speed without touching the camera. This is especially helpful for extra-long exposures of more than 30 seconds.

5.10 The Milky Way. (12-24mm f/4.0 lens at 12mm (19mm equivalent), ISO 1600, f/5.6, 30 seconds)

NOTE The Canon RS-60E3 Remote Switch (cable release) fits the Canon T4i/650D remote control terminal.

Jeff White’s Night Photography Tips

Jeff White is a well-known, urban night photographer in Michigan. Home, office, and restaurant designers have purchased his work to display on their walls. The following are Jeff’s tips for night photography beginners:

▶ Experiment with apertures and shutter speeds that you are unable to use during the day.

▶ Shoot in the RAW format so you have more creative control over the mixed lighting of night skies and artificial light sources.

▶ Experiment with moving objects while taking long exposures.

▶ Bring a flash or flashlight to illuminate smaller, closer objects, and add more depth to your shots.

▶ If you are shooting in a city or unfamiliar territory, take a friend along for safety.

Jeff captured this image with the Canon T4i/650D on the streets just outside Detroit. (ISO 100, f/5.6, 8 seconds)

Image courtesy of Jeff White

When shooting nighttime photographs, it is tempting to use the camera’s higher ISO settings, but if you are using a tripod, time is on your side. Consider using a slower or midrange setting, such as ISO 800 or ISO 1600, for better image clarity, color, and less noise. Night photographs tend to have more digital noise, so consider using your long exposure noise reduction Custom Function (C.Fn-4) to minimize it.

Photographing stars is always a treat. In just a few minutes of exposure, you can create an image of stars moving across the sky. To see a lot of stars and movement, you need to get away from the city and leave the shutter open. It can take minutes to hours to get the desired image. Make sure that your camera is securely mounted to a tripod, and that the tripod is anchored. Any movement can cause blurring in the photo. When considering night scenes, look for colors, shapes, and patterns. Expect to take more than one photograph at multiple exposure settings.

Painting with light is a fun technique that requires a slow shutter speed and a tripod. It is best to do it in a dark room or outside at night. Try leaving the shutter open using the Bulb setting (![]() ) or a long shutter speed, such as 30 seconds. Use a flashlight, match, or glow stick to write or draw a design in the air, as shown in Figure 5.11. If you are the subject, set the drive mode to Self-timer mode continuous (

) or a long shutter speed, such as 30 seconds. Use a flashlight, match, or glow stick to write or draw a design in the air, as shown in Figure 5.11. If you are the subject, set the drive mode to Self-timer mode continuous (![]() ) so you can take up to ten shots in a row without running back and forth to the camera.

) so you can take up to ten shots in a row without running back and forth to the camera.

5.11 You can use a flashlight to experiment with light painting. (ISO 400, f/5.6, 8 seconds, tripod)

Setting the aperture

When you see an amazing landscape with everything in focus, aperture played a role. A portrait in which only the eyes are in focus with everything else softly faded is also a function of camera aperture. Aperture is the diaphragm opening inside the camera lens that lets in light. Aperture numbering isn’t intuitive and can be confusing. The larger the number is, the smaller the opening; the smaller the aperture number is, the larger the opening. Most standard lenses range from f/2.8 to f/22. Some standard apertures are f/2.8, f/4.0, f/5.6, f/8.0, f/11, f/16, f/22, and f/32.

NOTE If no lens is attached to the camera, 00 is displayed as the aperture setting.

Think of depth of field as the area of focus around the subject. If there is a large area in focus surrounding the subject, then the photograph has a large depth of field, such as in landscape photography. If there is little focus around the main object of the photograph, then you have a shallow depth of field. For example, a portrait with a blurry background has a shallow depth of field. Unfortunately, you can’t make the statement that f/8.0 has a depth of field of 8 feet in front of, and 16 feet behind, the subject. The combination of focal length and distance between the subject and the camera determines the total available depth of field. In other words, each focal-length has a different effect on the depth field around the subject at the same distance.

A 28mm lens at f/8.0 that is 10 feet from the camera doesn’t have the same depth of field at the same distance as a 200mm lens. The 28mm lens spreads out the image and creates a larger depth of field, displaying everything in focus between 6 and 24 feet from the camera. The 200mm lens compresses the field of view, leaving little room for error with only 9.89 to 10.1 feet from the camera in focus. The Aperture-priority AE mode (![]() ) is good to use when depth of field is an important consideration. This mode lets you control the aperture, while the camera controls the shutter speed to create the proper exposure.

) is good to use when depth of field is an important consideration. This mode lets you control the aperture, while the camera controls the shutter speed to create the proper exposure.

If the camera is in the Program AE mode (![]() ), you can adjust the aperture by turning the Main dial (

), you can adjust the aperture by turning the Main dial (![]() ). Please note that if you increase the aperture, your shutter speed will be slower, and if you decrease the aperture, your shutter speed will be faster. Although the shutter and aperture numbers are moving up and down, the exposure stays the same because they are moving in proportion. If the shutter speed increases 1 stop, such as 1/60 to 1/125 second (which cuts the amount of light in half), and your aperture opens from f/8.0 to f/5.6 (doubling the amount of light), your exposure stays the same.

). Please note that if you increase the aperture, your shutter speed will be slower, and if you decrease the aperture, your shutter speed will be faster. Although the shutter and aperture numbers are moving up and down, the exposure stays the same because they are moving in proportion. If the shutter speed increases 1 stop, such as 1/60 to 1/125 second (which cuts the amount of light in half), and your aperture opens from f/8.0 to f/5.6 (doubling the amount of light), your exposure stays the same.

The following are some common situations in which you would use a large or shallow depth of field:

▶ A large depth of field is excellent when shooting landscapes, wildlife photography, or environment portraits (that is, pictures of people posing in their environment).

▶ A shallow depth of field is commonly used in studio portraits, sports, and fashion photography because it separates the subject from the background. A shallow depth of field adds a stylized look to your pictures. When you want a shallow depth of field, move in close to the subject. Fill the frame with different objects and see what happens. Use a lower aperture to add a new dimension to your photographs. Everything in a shallow depth-of-field image is not in focus. When using this setting, decide on a focal point—the part of the subject on which you want the viewer to focus.

5.12 This image has a shallow depth of field in both the fore- and background. (ISO 200, f/2.8, 1/400 second)

Setting the ISO

The ISO (International Organization for Standardization) setting is the light sensitivity of the camera’s digital sensor. The higher the number is, the less light you need to take a photograph. The lower the number is, the more light you need. For example, ISO 100 is perfect for a sunny day. ISO 1600 is good for indoor use. Each time you increase your ISO to the next step—from ISO 400 to ISO 800, for example—you double the light sensitivity. This allows you to increase the shutter speed or reduce the aperture by 1 full stop.

So why not use a high ISO setting, like ISO 6400, all of the time? Because high ISO settings create more digital noise than lower ones. Digital noise is the equivalent of grainy texture on film. Prints or enlargements of photos shot at ISO 6400 are not as crisp and clean as those at ISO 100. Not needing as much light is a nice advantage in dark rooms, but sometimes you do need more. Your Canon Rebel T4i/650D is expandable to 12800 ISO using Custom Function 2. This is helpful when you need a bit faster shutter speed, aperture, or can’t use a flash. However, ISO 12800 also has a lot more noise than the lower settings.

5.13 A low ISO setting was used to allow for a slow shutter speed and create a silky look on the water. (ISO 100, f/20, 1/15 second)

A fast shutter speed is important for stop-action photography, such as sports, animals, or children on the move. If you don’t have enough light to reach the desired shutter speed, then you need to adjust the ISO to a higher setting. Another advantage of a higher ISO setting is that the flash has a farther reach. If you are at an event, push the ISO higher to extend the reach of the flash across the room. How much noise can you handle? Your camera has the following eight ISO settings: 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400, 12800, and is expandable to 25600 for still photography with the camera’s Custom Function. When using ISO 3200 and above, the additional noise may be more than optimal.

The following guide might be helpful when setting the ISO:

▶ ISO 100-400. This range is ideal for sunny days.

▶ ISO 400-1600. Use these settings when shooting with overcast skies or in the evening.

▶ ISO 1600-6400. This range is ideal for night photography or when shooting indoors in low light.

▶ Custom Function 2. Here, you can set the ISO to 12800 for use in low-light situations.

Fortunately, there are a few options on your Canon T4i/650D that can help reduce the grain in your photos. Custom Function 5 is designed to reduce grain when you use high ISO settings, although it reduces digital noise at all ISO settings. You have the following four options with the high-speed noise reduction feature in Shooting menu 3 (![]() ) (in most cases, the Standard option should do the trick):

) (in most cases, the Standard option should do the trick):

▶ 0: Standard

▶ 1: Low

▶ 2: Strong

▶ 3: Disable

Custom Function 4 is for exposures of more than 1 minute. If you are not concerned about noise reduction related to long exposures, leave this setting turned off. The function has an auto mode that detects if an image took more than 1 second to expose; it then automatically applies the function. You may also leave it in the on position, which applies noise reduction each time an exposure of more than 1 minute is created.

NOTE If you activate a noise reduction function, you cannot take another photograph until the process is complete.

The Multi-shot Noise Reduction option combines four consecutive images at high ISO settings to create low-noise images. This mode also optimizes to reduce subject blur, making night photography much easier. You can find this option with High ISO speed NR listed in Shooting menu 3 (![]() ). You may also want to consider shooting in the RAW mode (

). You may also want to consider shooting in the RAW mode (![]() ). Both your Canon software and Adobe Raw have noise-reduction filters. There are also plug-ins available for Photoshop that help reduce noise.

). Both your Canon software and Adobe Raw have noise-reduction filters. There are also plug-ins available for Photoshop that help reduce noise.

The ISO settings in the basic zone modes are between ISO 100 and ISO 3200 (except Portrait mode (![]() ), which is fixed at ISO 100). The creative zone modes set the ISO between ISO 100 and ISO 6400. The auto setting for the Bulb shooting mode (

), which is fixed at ISO 100). The creative zone modes set the ISO between ISO 100 and ISO 6400. The auto setting for the Bulb shooting mode (![]() ) is ISO 400.

) is ISO 400.

Using Exposure Compensation

Your camera is packed with a lot of advanced technology designed to help you capture the best exposure, but this doesn’t mean you will always agree with its choices. If your photographs are regularly under- or overexposed, consider using exposure compensation to correct the problem.

If you photograph a white cat in the snow, the exposure may not turn out as you expect. You might need some help with all of the white light bouncing back to your camera, depending on the exposure mode you use. In this case, try overexposing the image to create a more accurate one.

Photographing a black horse in front of a dark background is another example of an extreme that might require exposure compensation. In this case, underexpose the photograph to better bring out the detail of the horse. When the main source of light is behind the subject, this is called backlighting. You can use exposure compensation to prevent unwanted silhouettes or the main subject from becoming too dark to see. This can happen if your subject is in front of a window or in bright sunlight.

CROSS REF See Chapter 6 for more information about lighting.

If you are not sure of the exposure you want to use, you can play it safe and bracket. Bracketing is taking multiple shots at different exposures. You can do this manually using the exposure compensation and taking one photograph at -1 (underexposed), another at normal exposure (or 0), and a third image at +1 (overexposed). This gives you three images with different exposure options.

Your camera is also equipped with Auto Exposure Bracketing (![]() ). AEB automatically takes three images—an underexposed image, a normal exposure, and an overexposed frame. You control the difference in the exposure range among the three images, up to 2 stops in 1/3-stop increments.

). AEB automatically takes three images—an underexposed image, a normal exposure, and an overexposed frame. You control the difference in the exposure range among the three images, up to 2 stops in 1/3-stop increments.

High Dynamic Range Photography

High Dynamic Range (HDR) is how photographers create colorful, high-contrast fantasy-like images of landscapes, cityscapes, buildings, or even people. HDR photos are made by combining bracketed images to create a new hybrid image. Each image brings different exposure merits to the final one. Some images capture highlights while others capture the shadow detail. Combined, they do what a traditional single image cannot: expose for detail in both highlights and shadow at a high level of accuracy.

Sometimes photographers manipulate images to create a fantasy effect. This is a popular technique among landscape photographers. Not everyone likes the surreal quality of this photography style. Remember that HDR images also can be adjusted for a more natural look. Traditionally, HDR photographs require a steady camera on a tripod to get multiple images of the same scene at a variety of exposures. This is one reason why you rarely see true HDR photographs of people or moving objects. The Canon T4i/650D has modes that can help you use the HDR technique. The nice thing about these modes is that you can hand hold the camera while shooting, if you are really steady.

5.14 This HDR image is a combination of three exposures. (ISO 200; f/10; 1/80, 1/200, and 1/500 second)

The Handheld Night Scene mode (![]() ) found in the basic zone (second to last position) takes four photographs while you are handholding the T4i/650D. It then creates one image that exposes for detail in the subject of your scene, while still allowing for ambient light.

) found in the basic zone (second to last position) takes four photographs while you are handholding the T4i/650D. It then creates one image that exposes for detail in the subject of your scene, while still allowing for ambient light.

The HDR Backlight control (![]() ) is one of ten modes found in the basic zone (last position). It takes three consecutive shots at multiple exposures in a backlit setting, and then creates a well-exposed image. This function displays the detail from the bright light source, such as the sky, as well as the subject in the foreground. I recommend using a tripod with this mode. The camera will not always line up the images correctly if there is camera shake.

) is one of ten modes found in the basic zone (last position). It takes three consecutive shots at multiple exposures in a backlit setting, and then creates a well-exposed image. This function displays the detail from the bright light source, such as the sky, as well as the subject in the foreground. I recommend using a tripod with this mode. The camera will not always line up the images correctly if there is camera shake.

If you take individual brackets without using your camera’s HDR features, the HDR Backlight control (![]() ), or the Handheld Night Scene mode (

), or the Handheld Night Scene mode (![]() ), you need software to combine the images. Although you can do this in Photoshop, one of the more popular programs is Photomatix. It gives you a good range of options to create both natural-looking and high-contrast, fantasy-style HDR images.

), you need software to combine the images. Although you can do this in Photoshop, one of the more popular programs is Photomatix. It gives you a good range of options to create both natural-looking and high-contrast, fantasy-style HDR images.

Exposing for Video

Auto exposure is a good standard for most of your video needs. When your camera is in the Auto Exposure movie mode (![]() ), it sets the ISO, shutter speed, and aperture.

), it sets the ISO, shutter speed, and aperture.

The Manual exposure mode (![]() ) is standard for advanced users, and it’s a good option once you are comfortable with your camera. It prevents your camera from changing the exposure during the middle of a scene. When shooting a moving subject, shutter speeds from 1/30 second to 1/125 second are recommended. It is also worth noting that it is not a good idea to change your exposure while shooting. The change will distract the viewer and signal that an amateur shot the video.

) is standard for advanced users, and it’s a good option once you are comfortable with your camera. It prevents your camera from changing the exposure during the middle of a scene. When shooting a moving subject, shutter speeds from 1/30 second to 1/125 second are recommended. It is also worth noting that it is not a good idea to change your exposure while shooting. The change will distract the viewer and signal that an amateur shot the video.

NOTE Remember that you can’t use exposure compensation when in the Manual exposure mode (![]() ).

).

You don’t have as many options for exposure in Movie mode (![]() ) as you do for still pictures, but there are a few. Exposure compensation is available in the Auto Exposure movie mode (

) as you do for still pictures, but there are a few. Exposure compensation is available in the Auto Exposure movie mode (![]() ), and this is helpful when photographing light, dark, or backlit subjects. You are limited to three stop adjustments in Movie mode (

), and this is helpful when photographing light, dark, or backlit subjects. You are limited to three stop adjustments in Movie mode (![]() ) (for still photos, you can make up to five). You also have Picture Styles available in the Movie mode (

) (for still photos, you can make up to five). You also have Picture Styles available in the Movie mode (![]() ). These are the same as those found in the still shooting modes. Picture Styles adjust color and tone based on the characteristic style or subject matter you are shooting.

). These are the same as those found in the still shooting modes. Picture Styles adjust color and tone based on the characteristic style or subject matter you are shooting.

TIP The ISO can be set anywhere between ISO 100 and ISO 6400, and expanded to 12800 in Movie mode (![]() ).

).

Composition

Have you noticed that most of the photographs you appreciate don’t have the main subject directly in the middle of the frame? This is because point-and-shoot photography (with the subject positioned in the middle of the frame) usually doesn’t capture the scene as well as a planned out and thoughtful composition. When it comes to composition, challenge yourself. Create variety in your photographs. Every scene or subject doesn’t have to be shot in the same way.

While your camera does so much for you, the one thing it can’t do is create your vision. The way that you see things is different from anyone else. The way that you frame an image is up to you, and that is what composition is all about. The Rule of Thirds and filling the frame are guidelines that can help you make good decisions when photographing the subjects in front of your lens. Another way to improve composition is to look for different points of view—every photo doesn’t have to be shot at eye level. Get down on your knees or climb up high (be careful!) to capture new angles. If you are photographing children, make sure that you get down on their level.

5.15 This image fills the frame with the foreground and also satisfies the Rule of Thirds. (18mm, ISO 200, f/4.0, 1/200 second)

Your choice of lens also plays a role in how you frame your shot. A wide lens spreads out a scene, which gives you a lot more real estate to work with in your frame. A long lens brings the scene or subject closer to you for a tighter shot.

CROSS REF For more about lenses, see Chapter 4.

Sometimes, even though you may be following the rules, some compositions don’t sit well with the viewer. Sometimes, it may be because part of the subject is cut off in an awkward position. There is nothing wrong with cropping your image later, but I don’t recommend that you shoot with the mind-set that you can crop during editing. Work on getting your composition right the first time. Later, if you notice that the image could still use some adjustments, you can crop.

TIP When cropping images, make sure that you don’t crop people at the knees or elbows—it looks awkward and uncomfortable to the viewer.

You have two ways to view a scene when developing a composition. You can use the viewfinder or Live View Shooting mode (![]() ). The Live View shooting mode (

). The Live View shooting mode (![]() ) is real-time viewing of the scene in front of the lens on the LCD screen. Some photographers find the screen on the back of the camera easier to use. However, this is not always the case—in bright sunlight, looking through the viewfinder is often the better choice. The flexible, 180-degree LCD screen is also helpful when holding the camera high over crowds, when shooting down low from a ground view, or even for shooting around corners.

) is real-time viewing of the scene in front of the lens on the LCD screen. Some photographers find the screen on the back of the camera easier to use. However, this is not always the case—in bright sunlight, looking through the viewfinder is often the better choice. The flexible, 180-degree LCD screen is also helpful when holding the camera high over crowds, when shooting down low from a ground view, or even for shooting around corners.

Rule of Thirds

I’m a firm believer that you need to learn the rules before you can break them. After you learn them, you can use the rules as guides. When it comes to rules about composition, the Rule of Thirds is the most important. The idea behind it is to mentally divide your camera frame into thirds, both horizontally and vertically. Combining the two creates what looks like a tic-tac-toe board, as shown in Figure 5.16.

5.16 This grid demonstrates the Rule of Thirds. Notice how the subject has been placed off to the side. (ISO 200, f/2.8, 1/500 second)

There are many ways to use this tic-tac-toe board on your camera. Consider the four cross sections in the frame as points at which you can place your subject. Another way to satisfy the Rule of Thirds is to mentally draw a diagonal line through the frame and photograph the main subject above or below that line. I also recommend that you fill the frame. It’s important to note, however, that sometimes you do want your subject in the middle of the frame. The Rule of Thirds encourages asymmetrical images, but that is not always the best result. In some circumstances, the best photograph is a symmetrical one, in which everything is balanced.

Horizon lines should follow the Rule of Thirds. The horizon line between the earth and the sky should not be in the center of your frame. It also should not cut through the back of the subject’s head. When photographing from a distance, the Rule of Thirds still applies. For example, a boat on the horizon should be placed anywhere but in the middle of the frame. Consider the direction in which the subject is moving, and then leave room in front of it to create a sense of motion. In the case of a runner, place him on the right side of the frame if he is moving to the left across the LCD screen.

Fill the frame

One way in which you can always satisfy the Rule of Thirds is to fill the frame, as shown in Figure 5.17. Don’t be afraid of the frame’s edge—you can get in closer. In fact, get as close as your lens allows and don’t worry if some parts are left out of the shot.

NOTE It is important to understand the limitations of your lenses. Some only allow you to get so close before proper focus is unavailable.

Lines and shapes

One of the most important rules of composition is that you have a focal point, which is something to which the eye is automatically drawn, or a starting point at which to view the image. The eye then follows a pattern, shape, or lines through your image. Understanding this concept is helpful, whether you are developing high-level conceptual ideas or just photographing your kids at the playground.

One of the first things a viewer’s eyes are drawn to is the lightest object in the frame. Leading lines take the viewer’s eye to the final destination of your image. S shapes are another nice compositional tool and geometric shapes can be very powerful. The triangle is the most powerful shape in art. Start looking at your environment. You will be amazed at the patterns you find around you. Parking lines, columns of streetlights, rows of corn, and architectural details, such as windows, are all good examples of everyday patterns.

5.17 Filling the frame with your subject gives the image a more personal feel. (ISO 100, f/5.6, 1/80 second)

5.18 I used lines here to lead the viewer’s eye to the subject. (50mm lens, ISO 400, f/9.0, 1/160 second)

Challenge yourself to look for patterns, and see if you can incorporate them with your subjects. Use leading lines to guide the viewer’s eyes where you want them to look. An S-shape takes the viewer on a journey across the page. You can also lead your viewer’s eyes into the distance with strong leading lines, or use them to create a vanishing point deep in the image.

Foreground and background

Most things do not happen on a single plane. You should consider the fore- and backgrounds as part of your composition. When you look at a scene, consider whether you should take a two- or three-dimensional photograph (see Figure 5.19). If you keep everything on the same focal plane, such as a straight-on shot of a building, it creates a flat look. You can add dimension to your photographs by placing objects in the fore- and background.

5.19 I used leaves in the foreground here to add dimension. (ISO 800, f/3.5, 1/4000 second)

You can also play objects off of the foreground. If you are shooting a mountain off in the distance, look around to see if there is something of interest to use in the foreground, such as a flower or an interesting rock. Consider how you can use the background, such as clouds moving behind a mountain, as part of your composition.

Keeping it simple

Many of the best compositions are great because they are simple. The saying less is more holds true in photography. Every part of your photo should be there for a reason. When in doubt, leave it out is another good rule to live by. Make it easy for the viewer to understand what you are trying to show. When you keep things simple, it is much easier to create an obvious focal point for the viewer, as shown in Figure 5.20.

5.20 This image was shot tight to keep the scene simple and avoid distracting from the subject. (100mm macro lens, ISO 1600, f/2.8, 1/2000 second)

A shallow depth of field is helpful because it sets the subject apart from the background. It also creates form and shape, rather than identifiable options in your photo background. Sometimes colors, lights, shadows, or shapes can also be used as compositional balancing tools in an image.

In the beginning, composition is something you think about if you are trying to improve your photos. Fortunately, over time, composition becomes a habit, and you will automatically place subjects a little to the right or left, and fill the frame. It just takes time and practice.